11. Overhauling Payment for Healthcare Goods and Services

“Let us not seek the Republican answer or the Democratic answer but the right answer.”

—John F. Kennedy

The process of funding, buying, and selling healthcare goods and services serves as the foundation of the entire healthcare system. How we handle these activities govern whether, when, and under what terms medical care will be available. If the underlying financial system is flawed and unsustainable, the rest of the healthcare system is guaranteed to be as well.

If we’re going to eliminate the defects of the current system while avoiding the wholesale creation of new problems, we need to do far more than tweak the current machine. What’s required is a complete overhaul. While inherently disruptive and challenging, the prospects are not as hopeless as one might think. One advantage that we have is that the system we’ll be building will be much simpler to understand and operate than the current one for virtually everyone involved. Another advantage is that the current system is so broken that simply tweaking it around the edges won’t make things better. The social and financial pressure to take definitive action will simply continue to grow.

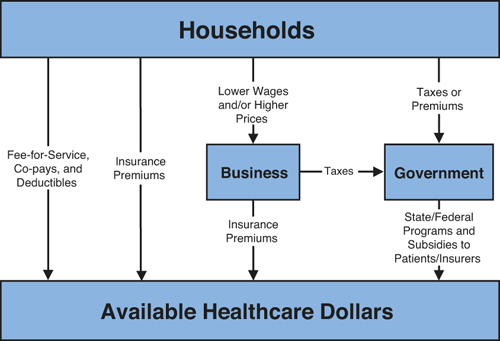

So where do we begin? Because the healthcare machine ultimately runs on money and self-interest, the logical place to begin is the source of that money. In his 1993 healthcare reform proposal, economist Uwe Reinhardt observed that every single healthcare dollar ultimately originates from American households. All the terms that we normally use to describe healthcare finance, such as employer-based purchasing, government insurance, and self-pay really refer to how those dollars are channeled rather than where they originate. This is illustrated in Figure 11.1.

Adapted from Reinhardt, U. “An ‘All-American’ Health Reform Proposal.” Journal of American Health Policy (May/June 1993): 11-17.1

Figure 11.1. Sources of Healthcare Funding

As this figure illustrates, the popular concept of health insurance as being “employer-based” or “government-sponsored” is somewhat misplaced. The healthcare dollars originating in households are diverted toward healthcare by one of three methods: (1) premiums paid directly by the family; (2) premiums that are extracted from households by employers in the form of lower real wages; and (3) premiums that are extracted from family income in the form of taxes. Because all dollars come from the same place, the real question is how we structure this collection to minimize the number of parts and amount of friction generated within the healthcare machine. Logic would suggest that one or even two mechanisms for collecting insurance premiums would be far more efficient than three, but which method is most practical?

We’ve already determined that the problems posed by risk-splitting can only be solved by requiring universal healthcare coverage. Universal coverage means that premiums must be collected paid on behalf of all individuals regardless of age, health, employment, or tax status. As it happens, the number of employees and the number of individual tax returns filed every year are fairly similar, totaling about 140,000,000. However, the number of tax returns actually represents a far larger percentage of households. This is because each employee in a single household will be counted separately in the employment statistics, while many people who are retired or not currently employed do file individual tax returns. On this basis alone, it makes more sense to rely on the mechanisms used for federal taxation to collect premiums rather than employers. There is another reason to avoid involving businesses in the process of collecting premiums, however. Every financial and administrative burden added to business reduces the financial resources available for businesses to use in their primary function: employing people. Any mechanism we can create that takes employers out of the loop wherever possible will maximize employment and personal income.* Taking employers off the hook leaves only two alternatives: self-payment and government-mediated collection of premiums.† Because the federal government would ultimately be responsible for monitoring and enforcing universal self-payment into the insurance pool, there is nothing to be gained by a system of enforced self-payment. That leaves us with using the current taxation infrastructure as the most logical collection mechanism. All premiums collected would be placed into separate, dedicated, individual or family accounts that may only be used to fund health savings accounts (HSAs) and purchase universal basic health insurance.

* It is useful to note that the few states that have mandated universal healthcare coverage have generally added to the societal burden of providing and tracking healthcare coverage. They have done so by increasing the number of entities involved rather than removing the burden from anyone. Employers who were already providing and administering health insurance programs derived no efficiencies from the program. In the case of Massachusetts, the total administrative burden of employers increased substantially. Employers with more than ten employees were, for the first time, required to provide a “fair and reasonable contribution” to the premium of health insurance for their employees. Many of these organizations are small businesses that have only three alternatives in the face of this mandate: (1) increase expenses and take the premiums out of profits; (2) reduce wages to employees to make up the cost of the premium; and/or (3) minimize the number of employees covered under the law.

† As Reinhardt points out, state and/or federal collection and stewardship of healthcare insurance premiums should not be considered or called a tax. Instead, individuals are simply channeling payments they would have made one way or another in any mandated universal health insurance program through the administrative functions of the government. These funds cannot and should not be used for any purpose other than providing a specified and uniform health insurance benefit—regardless of whether the insurer itself is the government or some other entity.

That said, there is no reason that the centralized funneling of premiums through the government could not be facilitated through a modification of the same mechanism used to collect payroll taxes. Payroll taxes are already used to collect funds for a variety of programs including Medicare. A modest modification to add another category would have relatively little impact on businesses.

Essential Elements of an Efficient Health Insurance Plan

A great deal has been written about universal health insurance. Books and articles seem to cover the topic from every possible perspective. Here we will focus only on what is needed to make a universal health plan efficient, rational, and sustainable.‡ We’re already determined that the system created should reduce the number of parts in the machine, ration overtly rather than covertly, and make use of market forces wherever possible. What do these requirements imply with respect to our universal insurance plan?

‡ Much of this discussion borrows heavily from the works of Drs. Fogoros and Reinhardt previously cited, as well as other work that will be referenced in turn. The author is grateful for the obvious amount of time and effort that they have put into their observations and written works.

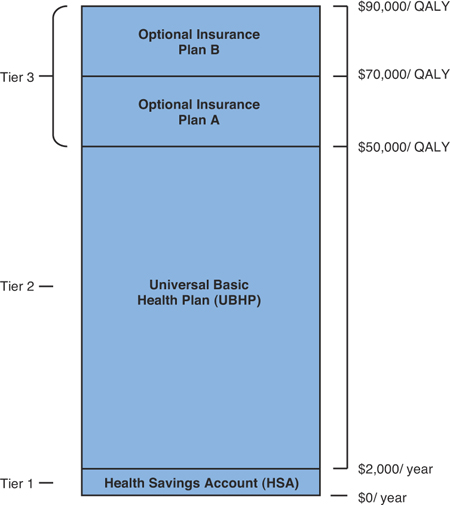

Figure 11.2 illustrates the elements of a universal healthcare system that meets our basic requirements.

From: Richard N. Fogoros, Fixing American Healthcare: Wonkonians, Gekkonians, and the Grand Unification Theory of Healthcare.

Figure 11.2. General Design of an Ideal Universal Healthcare Insurance System

What do all the terms in this figure mean and how does it work?

As shown in the figure, the sources of spending for healthcare goods and services are divided into various layers, or “tiers.” The first source of financing comes from the patient in the form of a health savings account (HSA). To fund the HSA, households with incomes above a given threshold are required to deposit a specified amount (in this example, $2,000 per adult or $1,000 for each child) into their healthcare account each year. These amounts and any interest that they earn would be nontaxable in a manner similar to Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs). “For households whose incomes fall below a certain lower threshold, these funds would be directly deposited into individual HSAs by the federal government. For households whose income falls between the lower and upper income thresholds, a sliding scale [would] be used to determine how much tax-deductible money they must contribute, and how much the federal government will contribute annually toward the individual HSAs.... Any money in the HSA that is not spent on healthcare during the course of the year remains in the HSA and earns tax-free interest. The money that accumulates in this fund is the property of the individual owner—the government has no claim on it and cannot tax it.”2 Except, as we shall discuss later, HSA funds can only be spent on healthcare.

If a family is relatively healthy over time, the amount of money in an HSA can grow considerably. These funds can be utilized in one of three ways. First, they can be rolled over into an IRA and used for retirement when an individual reaches retirement age. Second, excess funds can be used at any time to buy Tier 3 care services. Finally, there is a strong argument for allowing at least a portion of the accrued interest to be used for immediate personal spending. Most people have a financial time horizon that is quite short. It is important that they be able to realize some selfish near-term benefit to having funds remain in their HSA rather than spending it as quickly as possible—especially if these funds are coming from the federal government rather than from their own paychecks.

Regardless of how much they might have personally contributed to their HSA, it is very important that every American feel that the money in their HSA is theirs, and just as real and as valuable as any funds that they might have in their wallet, checking account, or retirement fund. From our previous observations, we have learned that incentives work, and that financial incentives in particular are extremely effective in producing specific behaviors. In our particular case, the behavior that we would like to produce in all Americans is a desire to consciously balance spending money on healthcare goods and services with the desire to keep their HSA account intact so that the accumulated wealth can ultimately be spent on nonmedical goods and services if at all possible. We’ll discuss exactly how HSA money is spent on healthcare services shortly.

The second tier of healthcare financing comes in the form of a Universal Basic Health Plan (UBHP) that covers every legal resident of the United States. The UBHP provides healthcare coverage under a system of open rationing.

In broad outline, all medical services that achieve a target level of cost-effectiveness are covered. In the example used in Figure 11.2, the UBHP covers all healthcare services that can be provided for up to $50,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). Services that consume more than $50,000 per QALY are not covered.Ӥ

§ Fogoros notes that “Using QALY as a cost-effectiveness measure is fraught with problems and is extremely controversial. The standard method of calculating QALY is not adequate for the rationing scheme we are proposing here.” The reader is referred to his book for a more detailed discussion of how ethical precepts can be used to guide rationing decisions, QALY calculations, and its use in explicit rationing. A detailed discussion on how to calculate QALY can be found by referring to: Sassi F, “Calculating QALYs, Comparing QALY, and DALY Calculations.” Health Policy and Planning Advance Access published on September 1, 2006, DOI 10.1093/heapol/czl018. Health Policy Plan. 21: 402-408.

A brief introduction to the concept of quality-adjusted life years will be helpful for readers who might not be familiar with the term. A QALY is an attempt to gauge how much good a particular medical intervention might generate with respect to two factors: its ability to extend life and the likely quality of the added life that will be obtained. One year of perfect health equals 1.0 QALY. One year of life with some degree of disability will reduce the QALY score by an amount proportional to the perceived reduction in the quality of life. For example, being unable to engage in normal activities for two weeks out of each month, but feeling fine the rest of the time, would be judged to reduce the quality of life for a patient by 50% over the course of one year, yielding a QALY of only 0.5. If a treatment were then made available that guaranteed complete recovery for a period of one year, it would result in a gain of 0.5 QALY. If that treatment happens to cost $1,000, the cost is $1,000/0.5 QALY = $2,000 for each QALY gained. If the same treatment is likely to work only half the time, the cost per QALY increases. In this case, it would increase to $1,000/(50% effectiveness × 0.5 QALY) = $4,000 for each QALY gained.

The point of trying to measure and use QALYs is that if healthcare resources are limited (as they inevitably are), we would like to have some means of deciding which tests and treatments give us the most total medical benefit for those scarce dollars. In the case of the proposed Universal Basic Health Plan, we can decide to cover any treatment that has a cost/benefit of some threshold level (for example, $50,000/QALY). At least theoretically, this approach will generate the most years of useful life for the country as a whole. This is in contrast to the current situation, in which Americans might be spending enormous amounts of money on expensive end-of-life treatments for some people, while failing to allocate enough money for relatively inexpensive therapies that would greatly benefit others for a long period of time. Another advantage to this approach is that the threshold of coverage can be easily moved up or down depending upon the funds that are available for use in purchasing basic healthcare goods and services. This is a far easier, fairer, and more rational approach to adjusting benefit levels than arbitrarily excluding specific goods and services or mounting administrative obstacles to care.

Although this approach is eminently logical, it’s not necessarily easy. One recurring concern with the use of QALY-mediated rationing has to do with the ethics of applying a raw value scale to individual cases. For example, a given treatment for cancer might have a very high QALY score in a 30-year-old, but a much lower score in a 75-year-old simply because of their age difference. This creates a situation in which the same treatment might be given to one person but is denied to the next on efficiency grounds—a situation that is problematic for many Americans. This conflict between “distributive justice” and “social benefit” has given rise to a balanced approach that has been dubbed the “Equal Opportunity Standard” (EOS). This approach goes a considerable way toward adjusting the QALY approach to meet mainstream standards for both ethics and economic rationality.** A second and more functional problem is that there is no complete “master list” of QALY scores for the vast majority of medical interventions. Because it is impossible to rank treatments without actual knowledge of their relative effectiveness, this is work that has to be done under any scheme for rationally allocating healthcare resources.

** In brief, the EOS approach modifies the standard QALY approach by incorporating a relatively small number of ethics rules. These rules specify whether and how adjustments will be made in the calculation of the quality-of-life index, the probability of treatment success, the duration of benefit, and post-therapy quality of life when coming up with QALY scores. The net result is an implementation of the QALY approach that balances the strict societal beneficence and strict distributive justice methods of allocating resources. For our purposes here, the important concept is that these tools exist and can be used to effectively and efficiently ration healthcare resources in a way that can be readily seen, calculated, verified, and understood by everyone involved in the healthcare system. Readers are referred to Fogoros’ Fixing American Healthcare for details of the EOS approach.

Comparing treatments is a substantial amount of work—work that has been largely neglected by most (if not all) healthcare systems around the world. Clinical trials and comparative analyses involved require substantial amounts of time, effort, and money. However, they represent money well spent, and represent a true capital investment that will lower overall costs over time, and not a consumptive expense. One approach is a four-step process:

- Establish a health standards commission. Composed of doctors, nurses, representative patients, and an advisory panel of economists, statisticians, and ethicists, the main job of the commission is to establish a system for determining appropriate values to use in cost-effectiveness calculations as described in subsequent steps.

- Establish one or more usable quality-of-life scale(s) for a range of health states. The purpose of the scale(s) is to assign a quality-of-life index to various physical disease states. This is an assessment of what fraction of full functionality is lost by virtue of different types of disease-induced disability. For example, it might be the case that living in a bed-ridden state is judged to result in a life that is only 25% of full functionality, whereas being in a wheelchair results in a quality of life that is 60% of full health.

Given the potential differences of opinion and the inherent subjectivity associated with this process, this task might be one of the most difficult and controversial that the commission must face. At one extreme, some might claim that the slightest disability dramatically reduces livability, while others might believe that quite severe disabilities leave one mostly intact. Nevertheless, it is doable. There should be no question in anyone’s mind that illness-induced disability does reduce the quality of life. The issue to be negotiated and resolved by the commission is by how much. - Develop an exhaustive list of condition-treatment pairs. A treatment pair consists of a condition (for example, strep throat) for which a specific treatment is recognized to be useful (for example, penicillin). Fogoros lists 11 elements to be determined in the course of this process. These include factors such as the probability that the treatment will achieve the desired effect on the condition being treated, a list of underlying medical conditions that affect the probability of benefit (for example, allergy to penicillin), the predicted duration of benefit (permanently if the strep throat is cured), expected impact of the benefit on quality of life, the influence of side effects, and the cost of the treatment. The total amount of information to be compiled is considerable, but manageable over time.

Although daunting, every possible treatment and condition does not have to be completely evaluated before a QALY-based system is implemented. Even if just half of the various medical conditions and treatments are reviewed and the comparative cost/benefit ratios on QALY calculated, a considerable amount of benefit can be derived by implementing the system around them—particularly if these are among the most important conditions financially. - The last step is to calculate the expected benefit and cost-effectiveness of each treatment considered. These calculations can be done automatically after determinations of the various parameters are known, and a specific patient is matched against a specific proposed treatment. Some estimates of benefit will be more accurate than others. For example, the probability of success of a given drug in a given patient really depends upon a number of variables (for example, the metabolism rate of the drug in the liver) that might be difficult or impossible to know with any certainty ahead of time. Nevertheless, the system proposed is still far fairer, more rational, and more efficient than any aspect of the current system.

A QALY-based system like the one proposed has many potential benefits, not the least of which is rationalizing our country’s healthcare research and development efforts. Current research emphasizes the development of medications and other treatments without respect to their cost. The result is often treatments that might be useful, but are so expensive that they will either result in bankruptcy of the healthcare system, or “crowd out” other healthcare services. The new system proposed will change manufacturer incentives from creating expensive therapies to creating therapies that have a relatively high cost-to-benefit ratio. A high cost-to-benefit ratio can be obtained in three ways: by improving effectiveness, by lowering cost, or by reducing side effects.

With the development of a practical QALY-based rationing system by use of the Equal Opportunity Standard, the third tier of healthcare financing now comes into play. No country can possibly pay for unlimited access to healthcare. By explicitly setting limits on the basic level of care that the country as a whole is willing to afford, a gap now remains for services that are still desired by patients but are too expensive relative to the benefits they provide. This gap can be filled by individuals purchasing additional private insurance that covers these services.††

†† Although some might argue that this creates a “two-tiered” healthcare system filled with “haves” and “have-nots,” the fact is that any system that does not provide every conceivable benefit to all citizens upon demand (a financially unsustainable proposition) will always be two-tiered. Nothing can stop patients from simply leaving the country to receive healthcare elsewhere if their medical desires are not satisfied at home. However, forcing them to receive their healthcare elsewhere simply deprives the healthcare system at home of dollars that could have been used to support universal care. From an socio-economic perspective, this is irrational and counterproductive.

Using Universal Coverage to Generate Efficiencies in Financing

Contrary to the expectations behind the Massachusetts and 2010 PPACA health reform laws, ensuring that everyone has access to health insurance does little to fix the system. Everything depends upon simplification.

Too Many Gears

The design of the Universal Basic Health Plan (UBHP) helps in a number of ways:

• Variances in state-mandated benefits are eliminated, as they are superseded by the terms of the UBHP. After the UBHP is implemented, federal laws must be passed that prevent the re-creation of nonuniform coverage requirements. The elimination of state-to-state insurance requirements will immediately reduce the administrative overhead associated with universal coverage.

• Standardization of benefits for the UBHP eliminates variability in deductibles and co-payments. Under the UBHP all deductibles and co-pays should become uniform nationwide. This step alone will obviate the need for millions of inquiries and transaction exceptions each day.

• It is easy to determine whether a given patient is covered for a specific condition under terms of the UBHP. An enormous amount of time and resources are currently consumed in determining whether a given healthcare visit or treatment is covered under the terms of each patient’s specific insurance plan and obtaining approvals and pre-authorizations. With knowledge of cost, effectiveness, side effects, and expected impact on quality of life, the new universal healthcare system will allow coverage determinations to be made instantly by use of universally accessible “coverage calculators” available to everyone on the World Wide Web. Relevant data regarding the patient, disease, treatment, and price are entered, and the cost per QALY is automatically calculated. Treatments exceeding the cost/QALY threshold of the UBHP are not covered universally, but can be purchased with funds from the patient’s HSA, Tier 3 insurance coverage, or personal savings.

This process is likely to result in new system efficiencies totaling many billions of dollars each year, and completely eliminate the paperwork and frustration associated with healthcare insurance pre-approvals, referrals, and denials. But these benefits are still going to be severely limited unless we can reduce the variability that patients and providers face in dealing with large numbers of disparate insurers and payment methodologies.

One way of addressing this problem is to go straight to a government-operated single-payer system of basic insurance. A great deal has been written about this approach, and there are even entire organizations devoted to its development and implementation.3 A common argument made by these groups is the need to reduce the administrative overhead expense incurred by insurers. After all, Medicare’s administrative costs are a small fraction of those insured by private companies.‡‡ Private insurers have to include the costs of advertising, commissions, taxes, and profits in their overhead, while government-run programs do not. And none of these costs include the administrative and financial burdens imposed on patients, providers, and businesses by public and private insurance plans alike. A recent study pegs this cost as being between $23.2 billion and $31 billion annually for providers alone, or nearly $70,000 per healthcare provider per year.4

‡‡ Depending upon the source, it is claimed that Medicare’s administrative expenses average somewhere between 2% to 5.2% of claims costs, while those of private insurers are somewhere between 8.9% to 25%. (Matthews M. “Medicare’s Hidden Administrative Costs: A Comparison of Medicare and the Private Sector.” The Council for Affordable Health Insurance. January 10, 2006. http://www.cahi.org/cahi_contents/resources/pdf/CAHI_Medicare_Admin_Final_Publication.pdf.

In a December 2008 study, McKinsey Global Institute estimated that the United States spent $91 billion more than expected on health insurance administration when compared to other countries and adjusting for GDP.5 This number grew to at least $108 billion in 2009. Of the 2009 expenditures, almost $40 billion consisted of sales, marketing, and general administrative expenses that are above and beyond that spent by other countries with an equivalent per-capita GDP. However, another $33 billion represents the excess administrative cost of running our public insurance systems such as Medicare and Medicaid. This might seem odd until one realizes that Medicare administrative costs have grown almost 30% annually since 2003. The increase is a direct result of two factors. The first is using private insurers to administer Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D benefits. The second is the rapidly escalating levels of regulation imposed by Medicare and Medicaid themselves.

What single-payer proponents miss is that it is unnecessary to move to a completely government-run healthcare system just to garner administrative efficiency. There is no reason why we cannot continue to have and utilize insurance from many different private companies. The trick is that the administrative components of the health plans that they offer under the UBHP must all be the same. If all private insurers are required to provide identical UBHP offerings with identical forms, processes, and procedures, administrative costs will fall close to the levels incurred under a single payer. The most efficient administrators of these plans would still be free to make a profit from doing so.§§ Regardless of who administers the UBHP, a role for private insurers will remain in the provision of Tier 3 coverage. Tier 3 insurance allows Americans to buy coverage above and beyond the level that our society can universally afford to provide for everyone. While insurers should be free to write these policies as they wish, it is in the best interests of the public, payers, and the healthcare system that certain elements of the UBHP be consistently applied to Tier 3 policies as well. In particular, Tier 3 policies should utilize exactly the same identifiers, applications, claims submission procedures, rules for payment, and paperwork as UBHP policies. The only difference should be the QALY limits covered by the policies. This requirement is critical for ensuring that the same fragmented and inefficient system of billing and administration we have currently is not resurrected in the future. We already know that this approach is wasteful and dysfunctional. It would be unconscionable to reproduce it.

§§ This approach would largely defuse the current controversy over the potential addition of a publicly operated healthcare plan. As long as the public plan and all privately insured plans under the UBHP have the same simple benefit terms, administrative forms, and requirements, prohibitions on covert rationing and premiums, there should be no reason that private plans could not compete based upon superior customer service. Private insurers would also have an opportunity to compete for customers wanting Tier 3 coverage. While some might argue that the terms of UBHP coverage removes the ability of insurers to “negotiate better pricing” from providers, there is absolutely no evidence that this currently happens in an economically sustainable or beneficial way. Instead, “negotiated benefits” simply end up being cost-shifted to others. For example, all of Medicare’s discounted fee “savings” are not savings at all, but simply costs being borne by patients in the form of provider rationing (providers close their offices to Medicare patients because they cannot afford to see them), or private insurers who must pay higher rates to providers to offset the Medicare cuts and allow those providers to remain in business.

Simplifying and Retooling Payment for Medical Services

The way we finance healthcare is important, but the entire purpose of financing is to compensate providers fairly and efficiently. If we want a healthcare system that delivers services efficiently and without wasting money, there is simply no substitute for simplicity in payment.

Physician payment in the United States is now based upon the performance of “procedures.” Compensation for each procedure is determined by the Rube Goldberg-esque RBRVS process. This has produced completely predictable results:

• Because the services of specialists are valued far more highly than the services of generalists, there is a relative shortage of primary care providers.

• Because they are rational, providers seek to maximize the number of high-value procedures performed and minimize the time required to perform them. When there is a choice between two equally efficacious treatments (for example, a medication versus a procedure), any economically rational clinician will be biased toward providing the procedure.

• Healthcare providers spend hours each week on billing and charting duties that have little or nothing to do with actual patient care. This effectively reduces the quantity of medical resources available to the nation. Some 40% of physician work time is now spent outside of the exam room.

• Because of its political nature, the existing payment system gives government bureaucrats and lobbyists disproportionate and unwarranted power to interject themselves into provider practices and the physician-patient relationship.

In redesigning and rebuilding a more efficient healthcare system, our task should be to craft a payment mechanism with five key characteristics. It must be:

- Simple, understandable, and easy to implement in any type of medical practice. Documentation requirements for payment purposes should be minimized.

- Consistent and reliable. It should make it easy to quantify and predict how much healthcare goods and services will cost.

- Subject to market forces. Prices should have the ability to rise and fall in response to levels of supply, demand, business expenses, and local conditions. Other things equal, this will have the effect of guiding patients and providers toward more cost-effective healthcare purchases.

- Free of clinical bias. In practical terms, this means that the system should give providers as little incentive as possible to recommend one course of action over another for financial (as opposed to clinical) reasons.

- Free of political bias, regulation, loopholes, and other intricacies designed to slow or minimize payments, or dictate the means by which healthcare services should be delivered.

All these requirements are in direct response to what we’ve learned about the complexity, inadequacies, and pitfalls of the current U.S. payment system. But what kind of system could possibly produce results like this? Oddly enough, the answer is the most obvious and common that one can imagine when buying professional services: Simply pay healthcare providers by the hour.

Simplifying Provider Payment Based Upon Well-Established Market Principles

A rational payment plan must take into account the economic incentives faced by patients and insurers as well as providers. There is an economic “balance of power” among these three parties that must be carefully maintained. If too much power accrues to patients, spending and the demand for services will grow out of control. If insurers grow too powerful, providers are easily victimized. Insurance benefit levels can rise or fall unsustainably depending upon whether the insurer is a government plying constituents with benefits for political reasons, or a private insurer seeking to maximize profits. If providers become too powerful, the price of care may climb to inappropriate and unsustainable levels. Healthcare is a three-legged stool. If any one of the legs is too long or too short, it’s nearly impossible to maintain a useful and usable equilibrium.

Taking advantage of market forces requires that: (1) prices are always publicly available and transparent to producers and consumers; (2) prices must be allowed to vary with supply and demand; and (3) regulation and obstacles to care have to be kept to the minimum required to protect the public and allow for orderly markets. The first two requirements can be accomplished quite easily by simply allowing clinicians to charge whatever they wish for their time, just like lawyers, accountants, and other professionals. A single hourly rate would cover their services, overhead, and other routine operating expenses.

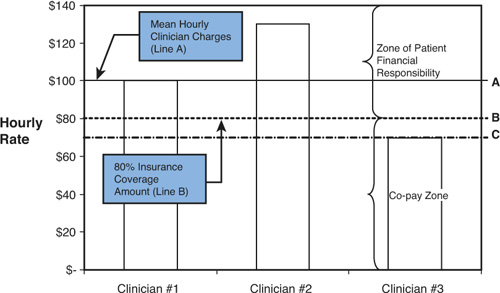

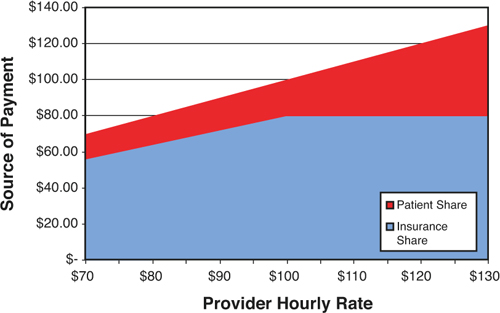

When compared to the surreal complexity of RBRVS, it seems astonishing that a simple, reliable, and understandable approach like this has never been seriously proposed. How would hourly billing for healthcare services work? The approach is illustrated in Figure 11.3. For the sake of this example, let’s assume that the average hourly rate charged by a particular type of clinician (for example, endocrinologists), in a given geographic area (for example, metropolitan Denver, Colorado) is $100 per hour (“Line A” in the figure).

Figure 11.3. Using Hourly Compensation to Balance Supply and Demand for Healthcare Services

Although $100 per hour is the average, it is important to understand that all clinicians are free to charge whatever they wish. In our example, Clinician #1 chooses to charge the mean, or $100 per hour, Clinician #2 charges 30% more, or $130 per hour, and Clinician #3 charges just $70 per hour. Every clinician is free to raise or lower her hourly rate at any time, but all current rate information (not only for clinician’s hourly rates, but also for these and other healthcare goods and services) must be posted and easily available to consumers at all times. The best place to post these rates is on a national website dedicated to this purpose. There, patients would be able to search for providers by price, specialty, geographic location, waiting times, and a host of other factors. This information would be entered directly into the site and kept current by each provider’s business office.

There are many reasons why providers might choose to vary and set their fees at different levels. Clinicians with a great deal of expertise and experience in a given field might believe that their services are worth more than average. Presumably they will charge relatively higher prices for this added value. New providers just out of medical training will have little experience and empty appointment slots to fill. They might want to charge lower rates in their quest to build their patient base and gain experience and revenue as quickly as possible. Still other providers will choose to offer plush offices, luxurious surroundings, 24-hour email access or other amenities, and will increase their rates to cover these costs. Clinicians wanting to serve poorer populations will minimize their rates to maximize patient access. Most importantly, providers who want to track and publicize their excellent clinical results will now have a clear incentive to do so, because those results will help justify higher charges. Patients should be willing to pay more for care that is demonstrably better than that provided by competing providers whose results are either unpublicized or not as good.

Where does insurance fit into all of this? With clinicians free to charge whatever they want, how much can we expect insurers to pay?

A reasonable answer, and the one that is most consistent with a free-market approach, is that the UBHP will pay for a substantial fraction of the average cost of healthcare goods and services within each geographic region. For the example, in Figure 11.4, we’ve set this level to be 80% of the average hourly rate for local providers.

Figure 11.4. Example of the Relative Contributions of Patient and Insurer Financial Responsibility at Various Provider Hourly Rates

Note: Assumes that basic universal insurance will contribute to a mean hourly clinician rate of up to $100 per hour, and a 20% patient co-pay for amounts up to $100. The patient pays for all hourly costs incurred in excess of the $100 per hour.

If the clinician’s hourly rate is higher than the 80% level established, the patient is responsible for 100% of the balance.*** In most cases this difference will be paid with funds from the patient’s health savings account. If the hourly fee is less than or equal to the 80% level, however, the patient is only liable for a co-pay for the charges covered by insurance. For example, if the provider charges exactly the allowable insurance rate of $80 for an hour of time and the co-pay level is 20%, the insurer will pay a total of $64 and the patient will pay $16 from their HSA. At an hourly rate of $100, the patient will pay $20 per hour, and the insurer will pay $80. Regardless of the amount charged for the visit, it is critical that the patient bear some financial responsibility to limit truly unnecessary care.

*** The fact that each American will have an HSA with a known balance at the beginning of each year will dramatically reduce the administrative overhead associated with billing and collecting patient balances. Financial institutions can be asked to issue HSA debit cards. Because the hourly rates charged by the provider and the hourly reimbursement paid by insurers under the UBHP are both known, the difference between the two can easily be charged to the HSA debit card at the time of service. This function alone will measurably reduce practitioner costs and allow them to reduce their hourly rates while preserving net income.

In the longer term, the average hourly rate will have an effect on insurance payments because it serves as a proxy for measuring the supply and demand of local provider services. If clinician-set charges consistently rise over time in a given locality, the supply of services is inadequate and the dollar value of 80% insurance coverage should be increased. On the other hand, if clinician-set charges decline over time, there is too much supply and the dollar value of 80% insurance coverage should be reduced accordingly. To accomplish this, a moving average of posted rates is maintained for each clinical specialty in each geographic area. Using the average of these rates as a benchmark, the dollar value of the 80% coverage level is adjusted up or down on a regular basis.

Many might scoff at the notion that provider charges might ever go down as well as up. Few of us have ever known a time when the price of anything associated with healthcare has gone down. But likewise, we have never known a time when the prices of most healthcare services were actually simple, clear, and readily known ahead of the time when the services are actually performed. When the price of healthcare goods and services is known, amazing things begin to happen.

Almost 30 years ago, Tierney, Miller, and McDonald published an article titled “The Effect On Test Ordering of Informing Physicians of the Charges for Outpatient Diagnostic Tests.”6 They performed a study that was remarkable in its simplicity. One hundred and twenty-one physicians were divided into two groups: a control group and an intervention group. Both groups displayed similar behavior when it came to ordering outpatient tests, both in terms of the numbers of tests ordered and the cost of testing per patient visit. Then, for a 26-week intervention period, both groups used a computer order entry system to request lab tests. The only difference was that physicians in the intervention group were shown the price of each test as it was ordered, and the total cost of all testing ordered on that day for the patient being seen. The result: Doctors in the intervention group ordered 14% fewer tests than those in the control group, and the charges for the tests that they did order was 13% less. Yet there was no measureable change in the clinical outcomes of the patients in the intervention group. And when the pricing information disappeared, so did the savings. After pricing information was removed in the 19-week period at the end of the study, the intervention group of providers immediately began ordering more tests, and the cost savings disappeared.

The amazing thing about this study is that neither group of physicians had any incentives whatever to reduce the number of tests ordered or the cost of doing so. There were no financial incentives or penalties. No government regulations. No capitation payment schemes in which doctors were rewarded for withholding care and punished for ordering more tests. They simply behaved naturally in the presence of information about pricing that is almost uniformly missing within our current heavily regulated, mind-numbingly complex, and price-opaque healthcare system. Imagine the impact if patients and providers both were to have ready access to pricing information about every medical expense and any alternatives.

If incentives are clear, prices are known, and payment is linked to the patient’s own perceived benefit, there is absolutely no reason that the price of healthcare goods and services cannot reflect market conditions. The cost of Lasik surgery—a procedure not generally covered by insurance—has declined dramatically over the past ten years while quality has improved. The cost of cosmetic procedures such as Botox injections and plastic surgery differs dramatically from place to place based upon market conditions. The real key to efficiency is a hitherto unused tool: rational patient choice.

Just as providers have the right to charge whatever they want, patients must have the right to use the services of any clinician, anywhere in the country, without having it affect the insurance benefits that they receive. Combined with ready access to pricing information, patients can then make rational decisions about which provider to use based upon many factors, including price. Just as providers might have any number of reasons for increasing or decreasing their hourly charges, patients will have many reasons for choosing one provider over another. Local providers will often be preferred over more distant providers on the basis of convenience. Providers with more experience in treating a specific condition may be chosen over providers with less experience. But price will be a factor common to every decision. Every patient knows that some or all of the charges will come straight from their HSA balance. Because HSA balances are “real money” (in that a percentage of the unspent balance can be used for discretionary spending each year, or rolled over to accrue interest that can be spent later), patients will have clear incentives to think twice before choosing a more expensive provider.

Although traditional HSAs are spent down completely before any insurance coverage is available, the long-term importance of cost sharing makes it worth reconsidering this approach. After a given HSA is used up, there is relatively little financial leverage that can be applied to patient care decisions (unless there is also a provision for continued spending from the patient’s own personal non-HSA funds). A better approach might be to ask patient HSAs to cover 100% of the cost of each new medical expense up to a lesser amount (for example, $150) before insurance cost-sharing kicks in. Other things being equal, this would preserve shared responsibility for a longer period of time. The free market system of time-based provider compensation has many other advantages over the current artificially complex system. The amount spent on billing and administrative overhead would plummet. While clinicians would still report the diagnoses, treatments, and procedures performed, actual billing would be based solely upon time spent—a very easy metric to measure and report. Because time is so easily tracked and documented, many of the opportunities for fraud and abuse that exist in the current system would disappear. Because providers are paid the same amount for their time regardless of interventions chosen for a given patient, they will have no incentive to perform more expensive procedures as opposed to using medical or educational interventions. And where government regulators are currently preoccupied with asking providers to measure and demonstrate their clinical effectiveness, a market-driven system will generate an immediate incentive to do so. Clinicians who are able to prove that they are clinically better will be able to attract more patients and charge higher hourly rates than their regional competitors—an incentive that most doctors currently lack.

Perhaps most importantly, the combination of QALY-based overt rationing and hourly compensation would go a long way toward restoring the integrity of the physician-patient relationship. Freed of conflicts of interest and CPT constraints on patient education, doctors can once again become honest advocates for whatever course of action is in the best interest of each patient, and take the time to fully explain the available options.

What are the potential drawbacks to this approach? There are two important changes that we can expect:

• Increases in waiting times. With less incentive to “crank out” patients and procedures as if they were widgets, fewer visits and procedures will be performed per unit of time. Many of visits that do take place will take longer. Combined with universal access to care, this will almost certainly lead to longer waiting times.

Whether this is a bad thing depends upon one’s perspective. On one hand, it is clear that trying to jam 30 minutes of care into the 7–10 minutes that primary care providers are currently allotted is inefficient and ineffective. Most of the education and counseling that would allow patients to understand and care for their medical conditions cannot possibly be provided in that period of time. In medicine as elsewhere, haste makes waste. On the other hand, in the short term, our supply of providers is essentially fixed. The net effect will therefore be better and more appropriate care, but with the appearance of waiting lists and lines we have not previously seen.

• Short-term changes in provider compensation. After market forces are allowed to take effect for the first time, some provider incomes will rise even as others fall. Longer waiting times in some specialties—especially primary care—will allow high-demand providers to increase their hourly rates. In most cases, compensation for these providers will rise significantly after being held artificially low by the politically determined RBRVS system. Reductions will gradually occur in the average hourly compensation of other groups of providers, but these will probably take more time to filter through. Most of these reductions will accrue to certain specialties that have been relatively overcompensated by performing large numbers of quick, but profitable procedures.

Having transferred the basis of compensation from procedures to time, it is reasonable to ask about checks and balances. What’s to keep clinicians from simply padding their hours? Could we expect expect routine checkups to take hours, as providers linger over every little detail? Although any compensation system carries the potential for abuse, there are several reasons to believe that healthcare is much less subject to time padding than many other professions, such as law and accounting. First, compared to attorneys and accountants, physicians and other healthcare providers are relatively scarce. There are only about 820,000 clinically active physicians in the United States, compared with more than 1,200,000 active attorneys. In practice, this means that the majority of clinicians are already booked to capacity. With full practices and waiting lists of patients to be seen, there is little or no reason for healthcare providers to dwell any longer than necessary on a given case. For most clinicians, heavy patient loads and waiting lists are a far greater concern than trying to fill idle hours. Second, unlike many other professions, most clinical services are delivered face-to-face. This allows budget-conscious patients to act as a restraining influence on visit times. Instead of looking for reasons to prolong their visit, patients will be looking for opportunities to speed it up. Third, truly transparent pricing will allow patients to screen providers based on price even before making their first appointment. High-priced providers will be under pressure to better meet the financial constraints of their patients.

Minimizing Insurance and Regulatory Overhead

The third requirement for freeing the healthcare markets—minimizing regulation and obstacles to care—is undoubtedly the most challenging to achieve and maintain over time. In the absence of any sort of free market in healthcare, the existing system has assembled an inexhaustible supply of administrative obstacles to care. These include referrals that are needed before patients can see specialists, pre-authorizations for treatments and tests that will inevitably be needed to properly manage care, provider panels that restrict who a patient can see without incurring financial penalties, and a wide variety of “passive aggressive” insurance behaviors.

Removing these administrative and bureaucratic limitations on care is going to be difficult for several reasons. First, it has traditionally been claimed that these limitations are needed to prevent patients and providers from over-utilizing healthcare resources. (It’s not clear whether this theory has ever been tested scientifically. If so, it would be even more useful to determine in what percentage of cases the test or treatment was appropriately denied, delayed, or canceled as opposed to being inappropriately denied, delayed or canceled.) Insurers will be loath to give up any measures that delay or discourage expenditures from their reserves. Second, as any parent knows, passive aggressive behavior can be hard to define. If the insurance company office in charge of billing questions is slow to respond to queries or answer its phones, is it intentional or simply inadvertent understaffing? Third, no matter how many of these questionable rules and hurdles might be identified and banned, it’s always cheap and easy to come up with new ones to replace them.

No matter how daunting the task, eliminating these obstacles once and for all is the only way to implement a system that is less expensive, more efficient and responsive to market forces. The alternative is the status quo: a public-private insurance system whose first allegiance is inevitably going to be protecting politicians and reserves rather than patients. Protecting patients, our pocketbooks and posterity is going to require a completely new way of thinking. With patients and physicians properly motivated, the burden of covert rationing must be placed on insurers. If an insurer wants to require physicians to obtain referrals or pre-authorizations, then it will need to justify its requests on a case-by-case basis. If valid claims are denied arbitrarily they may be appealed to a system of independent “claims courts” with the power to levy penalties on any party showing bad faith. Insurers who abuse their power must be punished, regardless of whether they are public or private. A national regulatory and investigative panel must keep careful and continuous watch over rules and policies that threaten to supplant market-based limitations on care with administrative ones.

Application of Market Principles to Other Healthcare Goods and Services

It is relatively easy to see how these same principles could be applied to pricing and providing many types of medical goods and services. In fact, an accepted precedent for this approach already exists in the form of “reference pricing” for drugs. In reference pricing programs, a baseline level of payment is set for the prototypical (and usually generic) drug within a given class of medications. In 2003, the German healthcare system chose the generic drug simvastatin (sold by Merck under the brand name of Zocor) to be the prototypical statin—a class of drugs used to reduce the amount of cholesterol in the blood. After the prototype was selected, the maximum amount that the German healthcare system would reimburse for any statin drug was set to be the full amount that the system would pay for simvastatin. Other drugs could certainly be prescribed and used, but the full difference between the cost of other statins such as Crestor and Lipitor and the cost of simvastatin would be borne by the patient. (In our case, this difference could come from the patient’s HSA.)

There are some legitimate criticisms of reference pricing. For one thing, it places a centralized bureaucracy in the position of determining which drugs are truly equivalent, even though they might not really be equivalent within the personal chemistry of an individual patient. Second, it has been persuasively argued that this approach stifles incremental innovation on the part of pharmaceutical manufacturers. If the baseline statin reduces cholesterol by 29%, and a drug company could create a new drug within the same class that would reduce cholesterol by 48%, why should they bother doing so if the insurance industry’s reimbursement policy forces most patients to make do with the inferior drug?

Many of these concerns have merit, but most of them can be addressed by modifications to the system. For example, a superior approach for long-term drug pricing would be to establish a reference based upon cost per QALY for an “average patient,” rather than simply choosing the cheapest drug in the class. This would largely remove bureaucratic and political concerns from the reference equation by providing and objective and verifiable alternative. The QALY approach would also have the benefit of encouraging the development of drugs that provide incremental improvements in performance, as long as their cost/QALY is less than or equal to comparable medications. The current system simply rewards the cheapest drug available with little or no regard for comparative efficacy.

Applying market-based pricing to non-emergency inpatient services is slightly more complex because so many different types of products and services are used in the course of a typical hospitalization. However, the same principles of transparent pricing, basic, uniform, universal insurance coverage, and market-based price adjustments can be applied. The optimum approach to hospital pricing might depend upon the purpose of the hospitalization. Hospitalizations for elective procedures (including foreseeable events such as childbirth) are probably best covered by a single, global, and well-publicized fee, much as they are now. This would give patients the ability to comparison shop, weigh data on experience, expertise, and historical results, and consider options such as traveling to different cities or states in an attempt to secure the best possible combination of price and outcome. Insurance coverage would follow a similar model to that for clinician services, paying a large fraction of the average procedure price for a given region. Patients choosing less expensive facilities—either within or outside their local region—would have the opportunity to minimize their own expenses. For proof, we can look at what happens when patients are fully responsible for virtually all their own healthcare expenses, and providers and institutions are free to operate on a free-market basis. Ironically, one of our best role models in this regard is India.

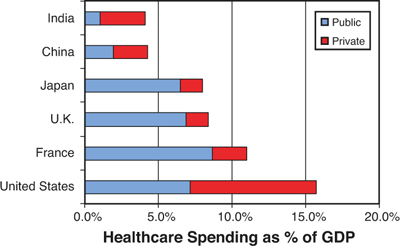

As shown in Figure 11.5, India spends very little of its GDP on healthcare relative to developed countries, and 80% of what it does spend is funded by patients, private firms, and charities. As a result, Indian healthcare providers have had to become both creative and price-conscious when offering services. Government has recently helped the innovation process by liberalizing restrictions on the industry, offering tax breaks for health investments in smaller cities and rural areas, easing restrictions on lending and foreign investment in healthcare, and encouraging public-private partnerships.7

Figure 11.5. Ratio of Public to Private Spending in Selected Countries, 2007

Data from: World Bank Development Indicators, 2010.

The result has been “a happy collusion of need and greed [that] has produced a cauldron of innovation, as Indian entrepreneurs have devised new business models.” Some notable examples:

• For years India’s private-health providers, such as Apollo Hospitals, focused on the affluent upper classes, but they are now racing down the pyramid. [One company]... plans to take advantage of tax breaks to build hospitals in small and medium-sized cities (which, in India, means those with up to 3 million inhabitants)... Apollo’s founder plans to do the same. He thinks he can cut costs in half for patients: a quarter saved through lower overheads, and another quarter by eliminating travel to bigger cities.

• Columbia Asia, a privately held American firm with more than a dozen hospitals across Asia, is also making a big push into India. Rick Evans, its boss, says his investors left America to escape over-regulation and the political power of the medical lobby. His model involves building no-frills hospitals using standardised designs, connected like spokes to a hub that can handle more complex ailments. His firm offers modestly priced services to those earning $10,000–20,000 a year within wealthy cities, thereby going after customers overlooked by fancier chains.

• LifeSpring Hospitals is a chain of small maternity hospitals around Hyderabad. “This for-profit outfit offers normal deliveries attended by private doctors for just $40 in its general ward, and Caesarean sections for about $140—as little as one-fifth of the price at the big private hospitals. It has cut costs with a basic approach: it has no canteens and outsources laboratory tests and pharmacy services. It also achieves economies of scale by attracting large numbers of patients using marketing. LifeSpring’s doctors perform four times as many operations a month as their counterparts do elsewhere—and, crucially, get better results as a result of high volumes and specialisation.”

• Nearly 60% of Indian hospitals use healthcare IT, but not in the same way as it’s typically implemented in the United States. “Instead of grafting technology onto existing, inefficient processes, as often happens in America, Indian providers build their model around it.”8

One has to wonder, if Indians can use market forces to innovate in healthcare, why can’t Americans?

Pricing healthcare services for emergency and nonelective services is more difficult, because by definition such circumstances do not lend themselves to data collection, deliberation, and consumer choice. The current approach uses a fixed-fee “prospective payment system” (PPS). The PPS uses about 500 so-called “diagnosis-related groups” (DRGs) to come up with a lump sum payment for given types of hospitalization services. If a hospital’s expenses for a given case are less than the amount set for the DRG, it makes money. If they are greater, the hospital loses money. There are two problems with this approach. First, hospitals do not necessarily have complete control over all their costs. Second, Medicare and Medicaid payments are often so low that it’s virtually impossible for hospitals to recover their costs. This combination can cause considerable trouble when profitable elective admissions are moved to more efficient and economical specialty hospitals or technology turns them into outpatient procedures. In their capacity as providers of emergency and nonelective services, hospitals are really functioning as public utilities. They cannot refuse emergency cases, discharge patients for nonpayment, or even decide whether and where to build new facilities without government oversight. Given these conditions, it is unreasonable for anyone to expect free markets to finance essential hospital services any more than they are used to finance police, fire, road, or sanitation services.

With these limitations in mind, there is really only one practical way to price nonelective hospital services appropriately: Continue the current prospective payment system based upon DRGs, but modify it to exclude elective procedures and minimize administrative overhead wherever possible. Elective procedures would be handled by using competitive pricing for elective services as described previously. If this approach is to work, we must ask hospitals to keep two sets of books for the services they provide—one for elective and one for nonelective services. Elective revenues derived through market forces should not be asked to subsidize nonelective admission expenses, or vice versa.††† A second requirement is that insurance payments for nonelective admissions cover the full cost of hospitalization. Current underpayments by Medicare and Medicaid are not sustainable over time, especially after elective-procedure revenue is segregated from nonelective expenses. Finally, patient cost-sharing for nonelective care must be structured differently from other medical expenses. Even the most conscientious patients can do little or nothing to influence the cost of true medical emergencies, and co-payments are of no real benefit for minimizing related expenses after the appropriate QALY measures are in place. On the other hand, this system does require that true emergencies be separated from emergency room and hospital abuse. Patients attempting to use emergency rooms as after-hour clinics should either be referred directly to 24-hour clinics set up to handle such patients, or charged twice the “normal” HSA co-pay for abusing the emergency care system.

††† Experience has now shown that mixing elective and nonelective care gives us the worst of both worlds: inefficient elective care and underfunded nonelective care services. For evidence, we need look no further than the growth of ambulatory surgery centers. Often built, owned, and operated by physicians, ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) are typically efficient, innovative, and profitable operations. As such, they are capable of providing excellent care faster and cheaper than conventional hospitals. Because they are not saddled with the high cost of providing emergency and nonelective care services, they represent a less expensive and more attractive option for patients who might have a bad knee but are otherwise well. In contrast, the conventional hospitals have high overhead and a burden of low-reimbursement emergency services that makes them uncompetitive in comparison. The resulting flight of elective procedures to ambulatory centers leads to a vicious cycle of declining hospital revenue and less experienced, less efficient surgical teams. The usual hospital response is to demand regulatory changes to reduce the attractiveness and increase the financial burden of ASCs. Unless elective and nonelective admissions are financially separated, there is really no way to achieve medical and economic efficiencies in either one.

Putting It All Together: Streamlined Healthcare Financing and Payment

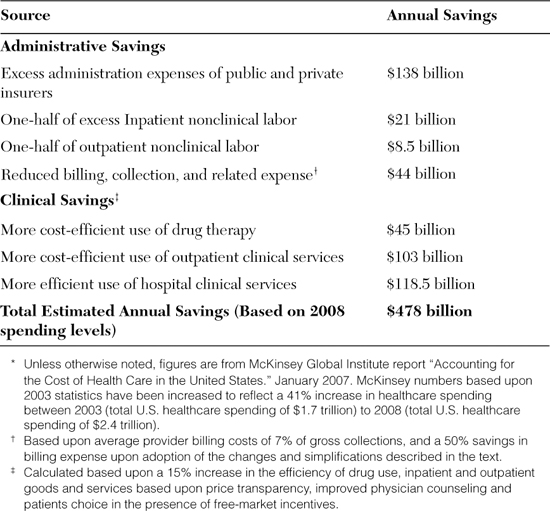

The net result of the changes we’ve described is to both reduce the number of parts in the healthcare machine and eliminate the majority of grit thrown into the system by the RBRVS-based payment system. A reasonable estimate of cost savings generated by these measures alone will total almost $500 billion annually, as shown in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1. Estimated Source of Annual Cost Savings As a Result of Described Changes to the U.S. Healthcare Financing and Payment System*

Where do these savings come from? Many of these estimates draw from McKinsey’s study of where excess spending occurs in the U.S. healthcare system, relative to what would be expected for the relative size of our GDP.

• Insurer administrative expense. According to McKinsey and others, in 2003 the United States spent about $98 billion more than expected for the administrative expenses of public and private insurance entities alone. This is the equivalent of $138 billion in 2008. Virtually all these excess expenses can be eliminated with claims and policy standardization and the simplification of impossibly complex RBRVS payment system. This estimate does not assume any reduction in insurance company profits.

• Nonclinical labor costs. These include estimates of cost in excess of “estimated spending according to wealth” (ESAW) for both inpatient and outpatient nonclinical labor costs. Nonclinical labor costs generally represent administrative overhead associated with regulatory compliance, billing, and sales and marketing, but excludes outside contract services, maintenance, professional fees, and utilities. Virtually all these excess expenses are attributable to the proliferation of insurers, rules, regulations, and exceptions caused by fragmented insurance coverage, differences between state laws, and problems caused by the complexity of the current payment system that are addressed by use of in-house billing staff. Virtually all these excess expenses (a total of about $30 billion) can be eliminated by a combination of de facto carrier defragmentation and reductions in regulatory burden. For the purposes of this calculation, we will attribute half of the savings to simplified payment mechanisms and half to reductions in regulatory burden.

• Reduced billing, collection, and related expenses. While some of the excess billing costs attributable to the current system will be accounted for under nonclinical labor costs, a large portion of the savings will come from a different accounting category: other operational costs and expenses. Many providers and hospitals outsource their billing and administrative support functions, and an entire industry does nothing but battle health insurer complexity, covert rationing, and counterproductive government regulation. The number and diversity of these companies is staggering. They include medical billers who gather data and prepare and submit the medical claims, couriers who transport the data, and thousands of software vendors. Computer software is used to enter and compile claims and insurance data, check it for errors and omissions, and configure it for submission to insurers. Software is also used by both insurers and providers in an attempt to game the system—denying or minimizing the dollar value of claims on one hand, and trying to maximize them on the other. Tens of thousands of people are required to create, sell, service, and maintain this software at an enormous cost. Other companies build their businesses around government regulations. These include state and federal requirements concerning continuing medical education, record keeping, credentialing, privacy, laboratory operations, and more.

The average clinical operation spends approximately 7% of its gross income annually on medical billing alone. With gross hospital and outpatient care costing a total of $886 billion in 2003, billing functions accounted for about $62 billion. This had increased to $88 billion by 2008. Insurance defragmentation (brought about by standardization of policies and administration), billing simplification, and use of self-guiding market forces should allow us to cut these billing costs by at least half, saving $44 billion annually.

• More efficient use of pharmaceuticals, outpatient, and hospital care services. The tragedy of covert rationing is that measures intended to reduce healthcare costs almost always end up having the opposite effect. Intentional complexity (no matter how well intended), cost opacity, deception, obfuscation, and regulation all create confusion and perverse incentives, producing ill-informed and/or irrational decisions on the part of patients and providers alike. Without a QALY-type approach, resources are wasted on what is payable, rather than what is effective and the best value for the money.

One very visible example is our current spending on end-of-life care. An astonishing 30% of annual Medicare spending goes to the care of the 5% of Medicare patients in their last year of life, and 78% of this amount—or almost one-quarter of all Medicare costs—are incurred in the last 30 days of life. A QALY approach to making healthcare purchasing decisions would reduce this spending dramatically, as many expensive and minimally effective treatments would fall outside of the cost/QALY coverage range of the Universal Basic Health Plan. Although some may bluntly object to the overt rationing involved in this process, there is considerable evidence that reducing the invasiveness and severity of end-of-life interventions is more humane as well as less costly to patients and society alike.

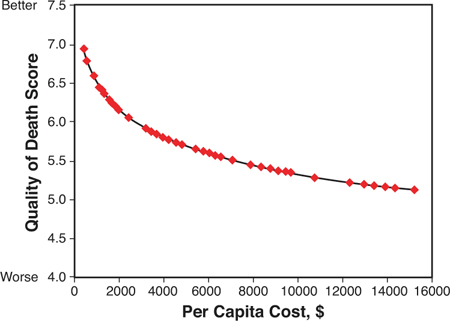

As shown in Figure 11.6, there is an inverse relationship between healthcare spending in the last week of life and the quality of death for cancer patients. The same study showed that having patients with advanced cancer and their physicians simply discuss end-of-life care wishes reduces the cost of care in the final week of life by 35.7%, or an average of $1,041.9

From: Zhang B, Alexi A, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. “Health Care Costs in the Last Week of Life: Associations With End-of-Life Conversations.” Archives of Internal Medicine 2009; 169(5):480-488.10

Figure 11.6. The Relationship Between the Cost and Quality of Life in the Final Week of Life

Knowing this, it’s worthwhile to compare the financial incentives inherent within the current system with those in the QALY and market-based system we’ve discussed. In the current system, providers aren’t paid to talk to patients, they’re paid to perform procedures—the kind of expensive procedures that will drastically increase the cost of end-of-life care. There’s an excellent chance that simply talking to a patient about care and end-of-life options would be considered a nonbillable event by insurers. The incentives inherent in the RBRVS system maximize both medical spending and the likelihood of a harsh and lingering death. When combined with cost/QALY-based insurance coverage, paying providers for their time will have the exact opposite result.

With savings like those resulting from smarter, less expensive, and more humane end-of-life care, it seems certain that the revised healthcare funding and payment systems proposed will generate at least a 15% reduction in the overall cost of providing any given level of healthcare benefits. Applied to the healthcare spending levels of 2008, these savings would total about $250 billion annually.

Altogether, the savings accrued by reducing the effective number of wheels in the healthcare financing system and reducing the complexity of payment will provide a considerable financial windfall even as they allow for a substantial increase in the quality of care provided. This windfall will almost certainly exceed the new cost of providing care to all Americans who are newly insured under the UBHP. Although the percentage of newly uninsured in the U.S. population will be roughly 16%, the healthcare spending reductions generated by our changes in insurance financing and payment alone total 20% of 2008 healthcare spending. We can spend the resulting financial windfall in one of two ways. The first is to take these savings and spend them on nonhealthcare goods such as debt reduction, tax reductions, or investments in our country’s nonhealthcare infrastructure. The alternative is to keep this money within the healthcare system and provide an even higher level of overall benefits. But we needn’t stop at these savings. There is still more we can do.