Content development: qualification of employees

Abstract:

As a third example of the content of training materials, this chapter focuses on the topic of employee qualification, a critical kind of training that can follow remediation in regulated industry. It further provides a comprehensive framework for an organizational approach to employee qualification. A typology of training is presented. Specific employee qualification considerations, including employee qualification as process, qualification status, and measures to demonstrate qualification are discussed. Employee qualification should be based on an assessment of complexity and criticality of the procedure. These concepts demonstrate an organized approach to employee qualification, compliant with regulatory requirements and expectations, and consistent with modern principles of risk analysis.

8.1 Introduction

This chapter discusses qualification of specific categories of employees in a GXP environment. Employee categories addressed include production operators and technical subject matter experts (SMEs). These personnel are designated for specific critical tasks in an organization. Concepts discussed herein are also applicable to laboratory analysts. This chapter is the third illustration of the development of training content, following the previous discussions of new employee orientation programs, associated GXP training, and continuing current good manufacturing practices (cGMP) training programs.

The first part of this chapter discusses types of employee training, including awareness training, training per se (which includes a paper-and-pencil assessment), employee qualification (i.e., training that includes a skill demonstration), and qualification of SMEs. The second part addresses types of qualification, including employee qualification as process and as status, as well as the use of SDAs in employee qualification.

The third part focuses on the rationale for qualification, highlighting the role the qualification process plays in deviation investigations and root cause analyses (RCAs). This part also considers the criteria for deciding what kind of training is appropriate for a specific procedure; this depends on the complexity and criticality of the procedure and the associated process. The final part delineates two other aspects of the qualification process, employee disqualification and employee requalification.

8.2 Regulatory basis for training

FDA requires employees in all regulated areas to be trained. For example, 21 CFR 58.29 states: “Each individual engaged in […] a nonclinical laboratory study shall have education, training, and experience, or combination thereof, to enable that individual to perform the assigned functions.”1 This requirement is repeated, with slight variation in phrasing, for other regulated areas (Table 8.1). FDA regulations say little more about training requirements. According to John Levchuk of the FDA, “The FDA has not published a guideline establishing acceptable procedures for personnel training, nor is a guideline being planned.” This point was reiterated by Vasilios Frankos, who stated, “At this time we have no plans to provide companies with training materials for their employees.”2

Table 8.1

FDA regulations for employee training

| Regulation | Regulated personnel |

| 21 CFR 58.29 | Non-clinical lab personnel |

| 21 CFR 110.10 | Human food handlers personnel |

| 21 CFR 113.10 | Thermally processed food handlers |

| 21 CFR 114.83 | Acidified food processing handlers |

| 21 CFR 120.13 | HACCP systems managers |

| 21 CFR 123.10 | HACCP systems managers |

| 21 CFR 211.25 | Pharmaceutical personnel |

| 21 CFR 225.10 | Medicated feed personnel |

| 21 CFR 600.10 | Biological products personnel |

| 21 CFR 606.20 | Blood component personnel |

| 21 CFR 820.25 | Medical device personnel |

| 21 CFR 1271.170 | Human tissue recovery personnel |

Several FDA guidances for industry provide more direction for training. In the Quality Systems Approach to Pharmaceutical cGMP Regulations, for example, FDA indicates:

Under a quality system, managers are expected to establish training programs that include the following:

When operating in a robust quality system environment, it is important that managers verify that skills gained from training are implemented in day-to-day performance.3

FDA has thereby provided an opening for each organization in regulated industry to develop its own training system that will ensure that its employees are appropriately trained for GXP compliance.

One often overlooked functional area where the use of standard operating procedures (SOPs) makes good business sense is in employee training. The development of a half-dozen or so training system SOPs – providing guidance for a number of areas such as task analysis, design and development of training and assessment materials, program rollout and evaluation, SME qualification, structured on-the-job trainer (SOJT) qualification, training advisory council of middle managers, and training metrics – would go a long way toward economizing an organization’s training resources. Some suppose that these SOPs would add to the “training burden” of the organization; our experience strongly suggests that the “burden,” such as it is, derives from the very absence of procedures. While training is a regulatory requirement, there is no requirement for the use of SOPs to guide and structure those training activities.

8.3 Categories of training

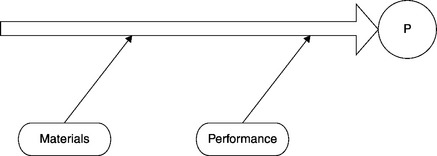

Before discussing qualification of employees for GXP compliance, let us first describe the respective categories and/or levels of training in the organization. It is possible to identify several levels of training in an organization. They make up a series, ordered by the complexity of training activities. From lowest level of complexity to highest, they include awareness training, training per se, qualification, and qualification of SMEs (Figure 8.1).

8.3.1 Awareness training

Awareness training, or familiarization training, is an activity that involves conveying subject matter to an audience, with the goal of making the audience aware of the content of the communication. This activity can barely be called training. The subject matter being communicated can be informational or actionable. An example of informational content is an organization’s announcement that layoffs will begin on a specific date. An example of actionable content is an announcement that the South Corridor will be closed for renovation beginning next week, and pedestrians should use the North Corridor until further notice.

Awareness training can take the form of a mass meeting in an auditorium, a “read-and-sign” document that is circulated to all affected personnel, an e-mail message, etc. Awareness training is typically documented by having the audience members sign attendance sheets, the buck sheet on a “read-and-sign” document, etc.4

In many organizations, “read-and-sign training” constitutes the bulk of training conducted. Organizations are now evaluating the appropriateness of “read-and-sign training” for certain types of procedures. Many times, implicit in this type of training is the organization’s need to exhibit due diligence to reduce its liability. The trainee signature is evidence of the organization’s due diligence. 5 Procedures for which “read-and-sign training” is not appropriate are being transitioned into the next higher level of training.

8.3.2 Training per se

The next higher level is training per se, sometimes called facilitation. This is an act of communication that intends to improve the workplace proficiency of members of the audience. Training per se includes the trainer (facilitator) or trainers, trainee(s) with various skill set(s) and disposition(s), training materials (including the training script) and assessment materials, training organization (i.e., supervisory factors, business case), facilities (i.e., allocated space, allotted time, utilities), and auxiliary materials (i.e., instruments and equipment, raw and in-process materials used in the training), etc. Training per se includes several delivery modalities, such as e-learning, mentoring, and classroom delivery.6The organization and its environment, within which the training activities, training organization, and training facilities are located, are also important for situating employees and their tasks. These categories can have a profound impact on the conduct and effectiveness of training per se.

Finally, training per se is complemented by an assessment that allows the trainer to assess whether the training intervention had (or did not have) the desired impact on the job, in the workplace.7 That typically takes the form of a knowledge transfer assessment (KTA), a paper-and-pencil quiz that predicts performance on-the-job. If trainee proficiency or non-proficiency has been correlated with a quiz score, so that high scores correlate with task proficiency and low scores correlate with non-proficiency, then the KTA is validated, and performance on-the-job can be predicted from trainee performance on the KTA.8

8.3.3 Employee qualification

At the third level, employee qualification is a kind of training augmented by a SDA. Employee qualification on a procedure or process is performed by a qualified trainer who is also a SME, or by a team consisting of a qualified trainer and a SME. The SME must have expertise in the procedure or process on which the trainee is qualifying. The qualified trainer is responsible for the documentation of the qualification event. The training is often conducted under SOJT programs. In the case of the team training, the trainer and the SME are jointly responsible for the documentation.

Employee qualification differs in several ways from training per se. Perhaps most importantly, training per se and qualification involve different systems within the brain of the trainee. Training per se tends to involve the declarative memory system, while employee qualification tends to involve the procedural memory system (Figure 8.2).

Both declarative and procedural memory systems are elements of long-term memory, as contrasted to short-term or working memory. Declarative (including semantic and episodic) memory is an explicit form of memory, where facts are stored and can be recalled and “declared.” Procedural memory, by contrast, is an implicit form of memory, whereby performances can be elicited without conscious thought.

The episodic memory system is related to the location or time of a personally-experienced event; an example would be the content of a particular training event that this trainee attended. The semantic memory system is related to facts that are not based on any personal recollection of episodic memory. An example would be identifying the pharmaceutical company with the highest global sales figures. The procedural memory system is related to a skill, such as motor or cognitive performance; an example would be operating a forklift truck.9

How do these memory systems relate to kinds of training? Training per se includes a paper-and-pencil assessment (KTA), which consists of recalling information provided in a particular training event, or else general knowledge such as the name of the book that Upton Sinclair published in 1906. Thus training per se engages the declarative memory system, either episodic or semantic.

Employee qualification involves a SDA that consists of the trainee independently performing the requisite workplace tasks, while being monitored and assessed by the trainer. Thus qualifications engage the procedural memory system. During the actual performance, the trainee may or may not be able to provide a declarative account of the task performance. If the trainee’s performance is indeed independent, it would not be recommended that the trainer engage in dialogue or ask questions. Instead, the “tell, show, do, and follow-up” cycle of SOJT can be augmented by a debriefing, wherein the trainee can give a declarative account should the trainer so desire.

8.3.4 Qualification of SMEs

The final kind of training is the qualification of SMEs. Employees are designated as SMEs in two ways. One is an experiential approach, based on management’s designation that an employee is a SME; the other is a formal approach, such as successfully completing a qualification program. Thus the process for qualifying SMEs is homologous to the process for qualifying trainers.

While the experiential approach may involve training of management to utilize specific criteria, to exercise good judgment, and to complete relevant documentation when designating this or that employee a SME, it does not involve employee training.

The formal approach to the qualification of SMEs does involve training. This kind of qualification is typically instituted by organizations that need to document that their SMEs are qualified, for instance if the organization is operating under a consent decree. Under such conditions, not only will the process of designating SMEs be formalized, but the role of SMEs in the writing of SOPs will be proceduralized as well.

Under these conditions, SMEs become qualified when they have successfully qualified on a number of SOPs that address the competences of their subject matter. The business owner usually identifies the particular SOPs that characterize the subject matter. The ensuing employee qualification process has two elements: overview training and skills training. Overview training (i.e., training per se that provides an overview of the subject matter), tends to be more conceptually focused, while skills training tends to be more performance oriented. Concepts tell what a thing is; tasks describe how to do something. Concepts provide the “science” for task performance. For example, the process of sanitizing equipment might be conceptualized as “reducing the levels of microorganisms and particulates to acceptable limits,” thereby minimizing the risk of product contamination from the equipment.

Overview training may be delivered by a qualified trainer in a classroom. There will be a SOP that will be the basis of this overview training, as well as a KTA. The event is documented in a training record where the facilitator and trainee concur that the trainee has successfully concluded the training (or not). Should the trainee be unsuccessful in the overview training, by procedure the trainee will have options such as repeating the training event at a later date, etc.

Once the overview training is successfully concluded, the trainee goes on to the SOJT events. The qualification event will usually be conducted one-on-one by a SME who is also a qualified trainer, as a SOJT event. There will be a SOP for each of the SOJTs in the module, as well as a SDA for each. The completed SDA form is then entered into the training tracking system.

Consider the typical SME qualification process for the use of vaporized hydrogen peroxide (HPV) for sterilizing controlled areas.)10 That SME individual training plan (i.e., curriculum) might include the following three modules and associated training events.

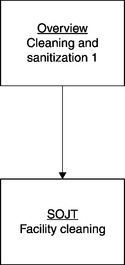

Figure 8.3 displays the initial module, which would include an introduction to cleaning, sanitization, and sterilization, followed by a SOJT session on facility cleaning. The training content would reflect 21 CFR 211.56(b) and (c), and the written procedures mandated there.

Figure 8.4 displays the next module, where the overview session might include further discussion on cleaning, sanitization, and sterilization. This is followed by one SOJT session on clean-in-place and another on sterilize-in-place.

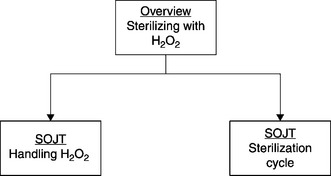

Figure 8.5 displays the final module in the training curriculum, which might include an overview of sterilizing with HPV, followed by one SOJT session on storage, handling, and preparation of hydrogen peroxide and another SOJT session on introducing HPV to a room, managing the sterilization cycle, and assessing the outcomes of the process. If the trainee’s performance is assessed as less than successful, by procedure this would be recorded in the training tracking system, and the trainee would be advised of the various options, including repeating the training process, etc.

After the trainee has been successfully trained to the relevant SOPs, and the three training records and the five SDAs have been entered into the training tracking system, the trainee is fully qualified. This means the trainee is ready to function independently as a SME in the use of HPV for sterilizing controlled facilities.

8.4 Qualification considerations

Qualification, in general, means fitness for some purpose, demonstrated by meeting necessary conditions or qualifying criteria. In regulated industry, “qualification” is used on the one hand in a process sense and, on the other hand, in a status sense. “Qualification” can mean the process of becoming qualified. This is “qualification” as a process, for instance “the qualification of the equipment on Line 28 is complete.” Closely associated with that usage is “qualification” as a status, as in “the hiring manager said that the candidate had all the qualifications for the position.”

8.4.1 Qualification process

Qualification as a process can be applied to anything (e.g., equipment, instruments, facilities, and computer systems). As Steven Ostrove states, “equipment, or systems, actually used as part of the production process for the production or manufacturing of a pharmaceutical or medical device product must be qualified prior to its use.” It can also be applied to personnel. Ostrove goes on to acknowledge that “the term ‘Qualification’ appears twice in Title 21 of the CFR: 21 CFR 211.25 – Personnel qualifications (and) 21 CFR 211.34 – Consultants.”11 According to the well-accepted approach to equipment qualification, there are three main phases to the qualification process: Installation qualification (IQ), operational qualification (OQ),12 and performance qualification (PQ).13

These three phases – IQ/OQ/PQ – can also usefully be applied to the process of qualification of personnel, as follows:

![]() Personnel IQ may be likened to providing objective evidence that the prospective trainee have the requisite education and background for the relevant SOP. If the SOP lists several prerequisites, documented evidence must indicate that the prospective trainee has completed training on each of these.14

Personnel IQ may be likened to providing objective evidence that the prospective trainee have the requisite education and background for the relevant SOP. If the SOP lists several prerequisites, documented evidence must indicate that the prospective trainee has completed training on each of these.14

![]() Personnel OQ may be likened to providing objective evidence that the trainee can function in the training situation (event) in an appropriate fashion. In a SOJT event, for example, this means the trainee performance is within the “control limits” set by the SOP. In the last analysis, this means that the trainee can perform the task correctly and independently.15

Personnel OQ may be likened to providing objective evidence that the trainee can function in the training situation (event) in an appropriate fashion. In a SOJT event, for example, this means the trainee performance is within the “control limits” set by the SOP. In the last analysis, this means that the trainee can perform the task correctly and independently.15

![]() Personnel PQ may be likened to the demonstration of acceptable performance during representative operational conditions. The trainee’s activities (e.g., on the shop floor or at the lab bench at the close of training) consistently produce a product that meets the standards set by the SOP or manufacturing order. In the GMP framework, the performances are directly related to the quality attributes (i.e., the SISPQ) of the regulated product.16

Personnel PQ may be likened to the demonstration of acceptable performance during representative operational conditions. The trainee’s activities (e.g., on the shop floor or at the lab bench at the close of training) consistently produce a product that meets the standards set by the SOP or manufacturing order. In the GMP framework, the performances are directly related to the quality attributes (i.e., the SISPQ) of the regulated product.16

Once the process of employee qualification is successfully completed, employees are qualified, and remain so unless and until they become disqualified.

8.4.2 Qualification status

Qualification as status, sometimes called certification, characteristically applies to persons. For instance, employees are sometimes designated SME because they are the originator of a new SOP. The reasoning for this practice is the following. An SME on a given SOP, who is a qualified trainer,17 can train another employee on that SOP. But who will provide the training to a new SOP? Who is to be the first mover? For a new SOP, there must be at least one SME, or compliant training will never occur. Those SMEs must be designated by management (in this case, the business owner), not because they have been through a qualification process, there is not any, but because they are the originator of the SOP, which is a status.

Occasionally an organization will develop a procedure that indicates employees are qualified when they have successfully executed the procedure three times. To be distinguished from various certified fellow employee (CFE) approaches to training, this approach requires neither a SME nor a qualified trainer. However, it appears to violate the predicate rule, personnel qualifications, which stipulate that “Each person engaged in the manufacture, processing, packing, or holding of a drug product shall have the education, training, and experience, or any combination thereof, to enable that person to perform the assigned functions.”18 This means that employees must be capable of performing assigned tasks prior to touching the regulated product. They already have the educational, training, and experiential status – they are not “learning as they go.”

8.4.3 Qualification measures

Qualification measures consist of SDAs. A training procedure for employee qualification stipulates how, when, and where the trainee can independently perform the task on relevant equipment.

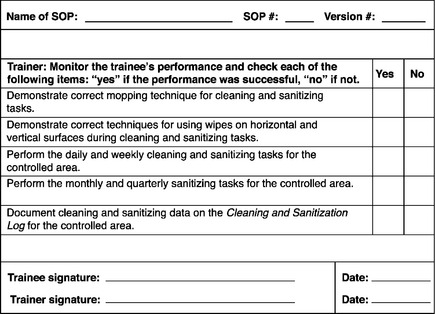

The training procedure will also stipulate that the trainer use a controlled form that is the SDA checklist. The SDA checklist has fields for entering the number and version of the relevant operational SOP. The checklist also includes a number of items that describe the identified critical or representative tasks to be assessed on the SDA. These are the items assessing the trainee’s performance (Figure 8.6). The trainee performs and the trainer (or some other SME) monitors the performance and checks each item in turn: “yes” if the performance was successful, “no” if not. When the performance is complete (whether successful or not), the trainee and the trainer sign and date the SDA. Area management may sign as well. The completed checklist is submitted to the data entry personnel of the validated training tracking system or, in case of manual data processing, to the staff of the document repository.

8.5 The rationale for qualification

Why should an organization qualify something or someone – be it equipment, computer system, facilities, or personnel? As we saw in Chapter 2, the stakeholders of an organization can observe various problems – an out-of-spec lab result or a manufacturing deviation, say – and report those problems to management. The responsible manager can initiate an investigation into the root cause of the probelem. Once the investigation report is complete, the manager can than implement an appropriate remediation.

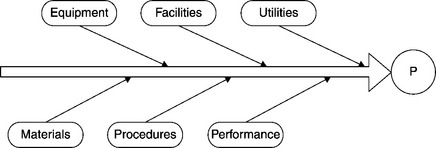

Candidates for the root cause of the problem include such process elements as equipment, facilities, procedures, raw materials, utilities, employee performance, etc. Consider the Ishikawa diagram displayed in Figure 8.7. The investigation proceeds along the same lines as we have discussed in Section 2.2, “The process of investigation.” Candidate elements are considered and eliminated from consideration, until only one remains. That remaining element is labeled the “root cause.” An element is removed from consideration once it is determined that it could not have been the root cause of the deviation. That is where the process of qualification becomes important. An excellent way to eliminate an element from further consideration as a root cause of a problem is by qualifying that element in advance.

Take equipment, for example. Installation qualification ensures that a piece of equipment, say an autoclave, has been installed within design specifications. Operational qualification ensures that the autoclave operates as designed and as required by the user. Performance qualification ensures that the autoclave displays continued suitability for its intended use. The IQ, OQ, and PQ of elements are critical for pharmaceutical, biotech, and medical device manufacturing and lab systems. Pharmaceutical, biotech, and medical device companies all must install, operate, and maintain equipment to be used in the manufacturing and laboratory system within design specifications, ensuring their operations are reliable and the quality of the output or product is consistent. In this case, the output of the autoclave is sterilized instruments.

When an autoclave is qualified, it is ensured that it has been installed according to design specifications, it operates in a reliable fashion, and that its output or product has a uniform (and high) quality. Thus the autoclave will not vary from design specifications upon installation. The autoclave will not vary from its specified range during the operation of the system. And its output, sterilized instruments, will not vary from the desired level of quality. Because there has been no variation of the autoclave that has been qualified, it cannot be the cause of the manufacturing deviation or out-of-specification lab result. Through the qualification process, that element can be eliminated from consideration in an investigation.

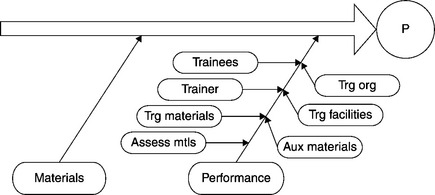

As the various elements are eliminated, the set of candidates for “root cause” decreases. Suppose the only elements remaining are raw materials and employee performance (Figure 8.8). The same approach can be applied to the performance element (i.e., employee performance). At some point the employees working on the process that generated the deviation had been trained on the relevant SOPs (or not). The constituents of the performance element include employees (who were the trainees), their trainer(s), the training materials and assessment materials, the training organization, facilities, and auxiliary materials utilized in training (Figure 8.9).

Each constituent element is considered and eliminated from consideration when it is determined that it could not have been the root cause of the deviation. The process of employee qualification provides an important way to eliminate a constituent element in advance.19

Was the trainer qualified? Were the employees (trainees) qualified? Remaining constituent elements can be analyzed in further detail. Thus if the training organization remains, it can be further analyzed into supervisory factors and business case. If the employees (who were the trainees) remain, they can be further analyzed in terms of skill set(s) and disposition(s). Was their morale low? If the category training facilities remains, it can be further analyzed into allocated space, allotted time, and utilities. Were the location and time adequate and appropriate? If the constituent element Auxiliary Materials remains, it can be analyzed into instruments and equipment, raw and in-process materials, etc.20 These further analyses would make up a more fine-grained version of the Ishikawa diagram.

This discussion has considered the rationale for qualification, highlighting the role the qualification process plays in deviation investigations and RCA. Employee qualification proves to be a relatively expensive kind of training, when compared to training per se. The one-on-one character of this kind of training, the adding of a qualification event to the training process, and other factors contribute to this expense. How does an organization determine which procedures require employee qualification, and which require only training per se? This raises the issue of the criticality of a procedure.

8.5.1 Critical procedures require employee qualification

An important consideration in determining whether the training will consist of training per se or employee qualification is the criticality of the procedure and the process it represents. A procedure is considered to be critical, if:

![]() The procedure requires a complex or highly skilled activity or a job for which a high skill level must be demonstrated to perform a task in the direct manufacturing of a regulated product.

The procedure requires a complex or highly skilled activity or a job for which a high skill level must be demonstrated to perform a task in the direct manufacturing of a regulated product.

![]() The procedure addresses employee safety, or may result in a business compliance risk to the company if not properly performed.

The procedure addresses employee safety, or may result in a business compliance risk to the company if not properly performed.

These criteria clearly reflect aspects of criticality and complexity that go into risk assessment.

Whether or not a procedure is deemed to be critical should be guided by three basic questions. What might go wrong with the associated process? What is the likelihood that this will happen? What and how severe are the consequences if this goes wrong?21

8.6 Disqualification and requalification

Qualified employees can be disqualified for multiple reasons. These include time-based expiration of training, extended absences, job changes, and other understandable reasons. Disqualification can also occur should performance on the job fail to meet qualification standards. This disqualification process can be the result of a management or quality assurance (QA) department observation of non-compliant performance.

Disqualification can also be the result of a pattern of exceptions that can be attributed to the employee, such as the following:

Management initiates the disqualification process. The QA department should review and approve any particular disqualification, as well as review and approve requalification standards and processes. The training department is responsible for monitoring disqualification and requalification events, as well as ensuring that the disqualification and requalification documents are submitted to the data entry personnel of the validated training tracking system or, in case of manual data processing, to the staff of the document repository.

8.7 Conclusion

While the FDA requires employees who work in controlled areas to be trained, it also provides latitude for organizations to develop their own training systems to make sure their employees are appropriately trained for GXP compliance. This chapter addressed key considerations in the topic of employee qualification, a critical kind of training in regulated industry. It further provided a comprehensive framework for an organizational approach to employee qualification. Concepts described in this framework should be incorporated in the organization’s training policy and procedures addressing employee qualification. These concepts demonstrate an organized approach to employee qualification, compliant with regulatory requirements and expectations, and consistent with modern principles of risk analysis.

A typology of training, ranging from the least complex kind, awareness training, through training per se (which includes a KTA), employee qualification (training that includes an SDA), and finally up to the qualification of SMEs was presented. Specific groups emphasized in this discussion include employee qualification and SME qualification. Next addressed were specific employee qualification considerations, including employee qualification as process, qualification status, and measures to demonstrate qualification. Qualification may be demonstrated by use of a skills demonstration assessment checklist.

We then focused on the rationale for qualification; highlighting the role the qualification process plays in deviation investigations and RCA. Employee qualification proves to be a relatively expensive kind of training compared to training per se. How does management decide which procedures require employee qualification, and which require only training per se? We discussed the criteria for deciding what kind of training is appropriate for a specific procedure; this depends on the complexity and criticality of the procedure and the associated process. The final part delineated two other aspects of the qualification process, employee disqualification and employee requalification.

8.9 References

Budson, A., Price, B. Memory dysfunction. New Eng J. Med.. 2005; 352(7):692–699.

Cooper, D., et al, Recruitment and Selection. Cengage Learning EMEA, Andover, UK, 2003:111–113.

Downs, S. Testing Trainability. Philadelphia: Nelson; 1985.

FDA. Guidance for Industry: Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Medical Gases, 2003. [Rockville, MD: CDER, May, p. 4].

FDA. Guidance for Industry: Sterile Drug Products Produced by Aseptic Processing – Current Good Manufacturing Practice, 2004. [Rockville, MD: CDER, September, p. 13].

FDA. Managing Food Safety, 2006. [College Park, MD: Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, April, p. 3].

FDA. Guidance for Industry: Quality Systems Approach to Pharmaceutical cGMP Regulations, 2006. [Rockville, MD: CDER, September].

FDA. Guidance for Industry, Process Validation: General Principles and Practices, 2008. [Rockville, MD: CDER, November].

Ferenc, B. Qualification and Change Control. In: Carleton F.J., Agalloco J.P., eds. Validation of Pharmaceutical Processes. 2. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1999:132–139.

Frankos, V. Overview of the Implementation of the Current Good Manufacturing Practices for Dietary Supplements Guidance for Industry, 2007. [College Park, MD: Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, 24 October].

International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH). Quality Risk Management Q9, 2005:2–4. [Geneva: ICH Secretariat, 9 November].

International Organization for Standardization. Sterilization of health care products. Geneva: ISO; 2000.

Levchuk, J., Training for GMPs – A Commentary presented at the. Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association program, 1990. [Training for the 90s, Arlington, VA: September].

Levchuk, J. Training for GMPs. J. Par. Sci. Tech.. 1991; 45(6):270–275. [November-December].

McDonnell, G. Antisepsis. Disinfection, and Sterilization: Types, Actions, and Resistance, New York: Wiley, pp.. 2007; 119–22:201–206.

O’Donnell, K., Greene, A. A risk management solution designed to facilitate risk-based qualification, validation, and change control activities within GMP and pharmaceutical regulatory compliance environments in the EU, Parts I and II. J. GXP Comp.. 10(4), 2006. [July].

Ostrove, S. Qualification and change control. In: Agalloco J.P., Carleton F.J., eds. Validation of Pharmaceutical Processes. 3. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2008:130.

Scannell, E.E. We’ve got to stop meeting like this. Train. Devel.. 1992; 46(1):71.

Shoenfelt, E., Pedigo, L. A review of court decisions on cognitive ability testing. 1992–2004. Rev. Publ. Pers. Admin.. 2005; 25(3):271–287.

Smalley, C. Validation of training. In: Agalloco J.P., Carleton F.J., eds. Validation of Pharmaceutical Processes. 3. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2008:523–528.

Weinberg, S., Fuqua, R., A stochastic model of ‘quality by design’ for the pharmaceutical industry presented at the. Pittsburgh Conference on Analytical Chemistry and Applied Spectroscopy. PittCon: Orlando, FL, 2010:5. [February/March].

1See 21CFR58.29(a), Personnel.

2See John Levchuk (1990), now available as Training for GMPs (1991); also Vasilios Frankos (2007).

3See FDA (2006) Quality Systems Approach to Pharmaceutical Current Good Manufacturing Practice Regulations. For other instances, see the following FDA Guidance for Industry (2003): Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Medical Gases; and FDA (2004) Sterile Drug Products Produced by Aseptic Processing – Current Good Manufacturing Practice.

4An example of such awareness training is FDA ALERT Training initiative: “The ALERT initiative is intended to raise the awareness of state and local government agency and industry representatives regarding food defense issues and preparedness.” Available from: www.fda.gov/Food/FoodDefense/Training/ALERT/default.htm There are no assessments.

5For the business risk assessment (as contrasted to the quality risk assessment) that is involved in an organization’s determination of due diligence, see the previous chapter.

6See Edward E. Scannell (1992), “Facilitation; all but unknown a decade ago, ‘facilitating’ has become the ‘in’ thing for trainers. Many trainers, in fact, have abandoned their ‘trainer’ hats and term themselves ‘facilitators’ instead.” An example is FDA FIRST initiative, which is closely related to the ALERT initiative. “Employees FIRST educate front-line food industry workers from farm to table about the risk of intentional food contamination and the actions they can take to identify and reduce these risks.” Available from: www.fda.gov/Food/FoodDefense/Training/ucm135038.htm Ten “Knowledge Check Questions” are included at the end of the FIRST training materials.

7E-learning is a special case of a communication or a training event. If the e-learning module lacks an assessment, it is a “page turner,” hence awareness training on a par with a “read-and-sign” document. If the e-l earning module includes an assessment, it is a training event, albeit special in the sense that it incorporates a virtual trainer.

8There is a substantial legal exposure to the use of invalidated KTAs (short quizzes), and there are serious costs to validating KTAs; see Elizabeth Shoenfelt and L. Pedigo (2005); also see Christopher Smalley (2008) for further discussion of KTAs.

9See, for example, Andrew Budson and Bruce Price (2005). They point out that the inferolateral temporal lobes are critical for the semantic memory system, the medial temporal lobes, including the hippocampus and parahippocampus, form the core of the episodic memory system, while the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and supplementary motor area are critical for procedural memory.

10See Gerald McDonnell (2007); also see International Organization for Standardization (2000).

13See FDA (2008) Guidance for Industry, Process Validation: General Principles and Practices, “Performance Qualification Approach.”

14As Christopher Smalley (2008) has put it:

How does a new employee become educated in the skills needed to perform their job safely and effectively? Imagine for a moment that we are performing an IQ similar to that for a new piece of equipment. Are your specifications adequate? That is, are the job description and other documentation that describe the job to be performed adequate? What are the minimum requirements for the employee being ‘installed’? op. cit., p. 519.

15On the closely related notion of trainability testing, see Dominic Cooper et al. (2003); also Sylvia Downs (1985).

16In a non-GMP framework, say OSHA, the performances are related elsewhere – say to the industrial safety of the employee.

17As Smalley (2008) has expressed it, “One of the best approaches to training on this content is to use the SME responsible for writing the procedures.” op. cit., p. 520.

18See 21 CFR 211.25(a), Personnel qualifications.

19As Smalley (2008) has expressed it:

“Let us recap some of the topics raised in implementing the ‘IQ.’ They are training requirements, training design, training execution, and evaluation of training. Embedded in these topics is the requirement to document,” op. cit., p. 520.

20The elements of auxiliary materials, for instance instruments and equipment, can be subjected to the same qualification process as the equipment element already discussed, even if they are used for training purposes only.

21ICH (2005) Quality Risk Management Q9, p. 3. See FDA (2006) Guidance for Industry, Q9 Quality Risk Management, p. 3; and Sandy Weinberg and Ron Fuqua (2010). See also Kevin O’Donnell and Anne Greene (2006).