Final implementation

Abstract:

This chapter reviews the scope and impact of FDA regulations for the life sciences industry in general, and for training in particular. Any person who touches the regulated product, or who supervises that person, falls within the scope of the regulations. These persons must be trained on SOPs, insofar as they relate to the employees’ functions, prior to their touching the regulated product. Thus it is critical that the final implementation of the training module includes all these employees. Next, a widely used approach to ensuring that employees are trained before they touch the regulated product is critically examined. A supervisor is required by SOP to ensure all necessary training and qualification requirements in the employee curricula are completed and documented prior to assigning an employee to a task. The shortcomings of such an approach are detailed, especially the failure to provide the supervisor with necessary information about the accuracy and currency of the employee curricula. Finally, an alternative approach involving a controlled document that includes a Target Audience List is proposed. This document facilitates the communication necessary to ensure the requisite training has taken place.

13.1 Introduction

The final implementation of a training module comes among the last phases of the program improvement model. A performance gap or a training gap has been identified in the corrective action and preventive action (CAPA) plan as a result of a revision of a standard operating procedure (SOP), and a carefully planned approach to address the gap was prepared. If management approves the design, the training program, including training materials and assessment materials, has been created in the development phase. These training materials and assessment materials are rolled out in a pilot implementation, a proof of concept study, highlighting the iterative feature of the program improvement model. In the case of a pilot implementation, the results of the program evaluation are fed back, closing the loop, facilitating further refinement of the training program. In the evaluation phase this is called a “formative evaluation.” Further design and development efforts follow, until the module meets organizational needs. Then comes the final implementation of the module.

In this age of technological change, much attention has focused on the timing of training. On the one hand, training is optimally delivered close enough to task performance to ensure that the skill enhancement is still relevant but not yet forgotten. These requirements have led to just-in-time training (JITT), which has benefited from e-learning and other developments.1 However, in the pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, medical device, blood product, and other FDA regulated industries, the need for optimal delivery of the training is constrained by the requirement that employees be trained before they “touch” the product.

At first glance, that requirement might seem to be trivial – just ensure that the training has been delivered “before,” and be done with it. But the very dynamic of change that has driven manufacturing technologies as well as e-learning can create a climate of turbulence in process and procedure that makes ensuring “before” very dicey, and raises the prospect of serious compliance consequences if it turns out to be “after.” The requirement that employees must be trained before they touch the product becomes especially acute in the case of final implementation of a training module, when it is no longer a matter of selecting the trainees as it is in the case of a pilot. Each and every employee impacted by a new or revised procedure must be trained. In this chapter we will examine that problem and consider several approaches to addressing it.

13.2 Scope and impact of FDA regulations

The FDA regulations for pharmaceutical manufacturing, set out in 21 CFR 211, are comprehensive in both scope and impact. Regarding scope, these regulations provide guidance for each person engaged in the manufacture, processing, packing, and holding of a drug product. The phrase “each person” includes both employees and supervisors.

The phrase “manufacture, processing, packing, and holding” is also comprehensive – it includes packing and labeling operations, testing, and quality control of drug products. In sum we can say the scope of the regulations includes any person who is (a) touching the drug product, or (b) supervising the persons who are directly touching the drug product.2

How do these FDA regulations impact on these persons? The regulations require that the pharmaceutical manufacturer develop written SOPs that provide guidance for a broad range of activities. These must be written procedures. As an example of the failure to meet this requirement, consider the FDA Warning Letter to Greer Laboratories, Inc., dated 24 June 2005: “Your firm failed to establish written procedures applicable to the function of the quality control unit.”3

So a set of SOPs are required that will provide comprehensive guidance for dealing with the inputs, processes, and outputs of drug manufacturing, as well as quality control over this manufacturing. Not only are written SOPs required; the regulations insist the quality unit approves them – they are controlled documents – and the procedures be followed.

These written procedures must be followed. As an example of the failure to meet this requirement, consider the FDA Warning Letter to Intermax Pharmaceuticals, Inc., dated 13 May 2003: “Although your firm has a written procedure for training; it was found that these procedures are not followed.”4

Moving from the general to the particular, the FDA regulations stipulate that all employees and supervisors be trained. 21 CFR 211.25(a) states that each person engaged in the manufacture of a drug product shall be trained:5

1. in the particular operations that the employee performs; and

2. in current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs);

3. including the cGMP regulations in chapter 211; and

4. the dozen or so written procedures required by these regulations.

The scope of this training will “relate to the employee’s functions;” the objective of this training will be “to enable that person to perform the assigned functions.”

Moreover, 21 CFR 211.25(b) goes on to say that the supervisors of these persons shall be trained so as “to provide assurance that the drug product has the safety, identity, strength, quality and purity (SISPQ) that it purports or is represented to possess.”

Three points follow from these stipulations. First, employees must have technical (or skill) training in their particular assignments. Second, the employees must have training in cGMPs that constrain the exercise of skills. Third, supervisors are responsible for the SISPQ of the drug product, and must be trained to fulfill that responsibility.

13.2.1 Training, or the lack thereof

How have companies within the scope of 21 CFR 211 responded to these requirements? We have reviewed the FDA GMP Warning Letters sent during the five-year period between January 2003 and December 2007.6 There were 25 Warning Letters that mentioned deviations regarding aspects of 21 CFR 211 during that time period; they listed a number of observations that the FDA investigator had made during site visits to companies within the scope, including such issues as cleaning, contamination, sampling, etc. Seven of these Warning Letters (over 25%) also cited inadequacy of training, or inadequacy of the documentation of training – including inadequacy of skills training, training in GMPs, and supervisory training.

This pattern is not a historical anomaly; the FDA has been concerned about the adequacy of training in the pharmaceutical industry for some time. For example, regarding a somewhat earlier time period, FDA Senior Compliance Officer Philip Campbell asked “Are the employees trained?” He further inquired “Are the supervisors trained?” Finally, he asked “Are there records of that training, and is it ongoing?”7

The fact that more than a quarter of these FDA findings point to problems in training should not come as a surprise. However, as we have seen, whenever there is a remediation (CAPA) for any deviation investigation or regulatory observation, that remediation will usually involve a revision of procedure or other controlled document, which in turn almost invariably involves training on the revised SOP. As Carl Draper, Director of the FDA Office of Enforcement, has put it, “The implementation of revised SOPs should include employee training.”8 So training will be the indirect outcome of a remediation, and will be the focus of some attention in the follow-up of the CAPA. Thus we expect that any Warning Letter – directly addressing issues of cleaning, contamination, lab work, sampling, testing, utilities, whatever – may also include a call for training, or for better training.

However, it seems that the FDA has come to expect ineffective training,9 or inadequate documentation of training.10 These expectations, along with the relative ease of assessing the occurrence and documentation of training via the ubiquitous tracking systems and learning management systems (LMSs), make the investigator’s focus on these areas understandable.

13.2.2 Training versus “Re-training”

Recognizing the inadequacy of training does not amount to a call for “re-training.” There is a substantial difference between training as an indirect outcome of a CAPA, and “retraining” as a direct outcome of an investigation, as a CAPA itself. Regulatory investigators quickly recognize the fallacy of “re-training” as a solitary or even major remediation.11 For an example of such a fallacy, consider FDA Adverse Determination Letter regarding the Baltimore manufacturing facility of the American Red Cross, dated 27 July 2006. A Red Cross employee had not been trained before touching the whole blood product. When this problem was discovered two months after the event, the Red Cross conducted a root cause analysis (RCA) and concluded that this was a training problem, “The corrective action was to fully re-train all employees.”12 The FDA responded that “as a result of the incomplete investigation, [the Red Cross] failed to determine all root causes of the problem.” (ibid.) The Red Cross was then fined more than $700 000.

A manufacturing unit is strongly inclined to release an impounded batch by declaring that the catch-all category “human error” was the root cause of the deviation or failure, and suggest “re-training” of the employee(s) as the corrective action. This is goal displacement;13 it places the unit’s goal, releasing the batch, above the organization’s goal, which is identifying the root cause and implementing a remediation that will ensure the deviation will not recur. This goal displacement results in a false alarm, where re-training is the direct outcome of an investigation. The fallaciousness of re-training is amply demonstrated – re-training, re-training, re-training of the same employee(s), ad infinitum. As Philip Lindemann points out, “Not identifying the cause of failure may lead to additional failures.”14 The regulatory investigator will recognize this – as will upper management if there are metrics tracking CAPAs. The regulatory investigator, and upper management, will thereupon question the adequacy of the organization’s investigations.

Moreover, if “human error” was proposed as the root cause of the deviation requiring “re-training,” then the actual root cause would be:

![]() inadequate training materials;

inadequate training materials;

![]() an unprepared or incompetent trainer;

an unprepared or incompetent trainer;

![]() ineffective interaction of trainee(s) and trainer; or

ineffective interaction of trainee(s) and trainer; or

![]() some combination thereof.15

some combination thereof.15

For none of these cases would remediation be as simple as “re-training,” since the trainee would need to be motivated, the training materials would need to be revised, the trainer would need to be qualified, or the interaction would need to be enhanced before the remediation could go forward.

When John Levchuk calls for Reinforcement Training as a remediation for “future skills deficiencies,”16 he indicates that refined or redefined training materials may be indicated, since “usually, only those skills most likely to be forgotten or suffer compliance erosion over time would be targeted for inclusion in a periodic reinforcement program.”17 Moreover, when he goes on to call for Remedial Training as a remediation for “acquired skills deficiency,” he states that it would be “more appropriate and efficient if it were targeted to an incumbent’s specific skills deficiencies.” Thus Levchuk is not calling for “re-training” in either case.

In this part we have reviewed the scope and impact of the FDA regulations of pharmaceutical manufacturing in general, and of training in particular, and found them to be comprehensive. Any person who touches the regulated product, or who supervises someone who directly touches the regulated product, falls within the scope of the regulations. These regulations impact on these persons via written SOPs that provide comprehensive guidance for dealing with the inputs, processes, outputs, and the quality control of drug manufacturing. These employees must be trained on these procedures insofar as they relate to the employee’s functions, so as to enable that person to perform the assigned functions. As the process and procedures change, the impacted employees must be trained in a timely fashion. Hence the critical issues of timing attending the rollout of a finalized training module.

13.3 The typical organizational response

In many cases, an organization will realize that it must take further steps to ensure that employees are trained on the relevant SOPs before they touch the regulated product. Sometimes this is a result of a deviation investigation or an audit observation. Other times it may be the result of cost considerations, seeking to reduce rework and reprocessing, or because of compliance concerns. In any case, a typical response is to develop a new SOP that calls upon supervision to check the employee’s training status. We will refer to such a controlled document as a “Task Assignment Procedure.”

Such a procedure might require that the supervisor ensures all necessary training and qualification requirements have been completed and documented prior to permitting an employee to work independently. This check is typically performed by looking at the employee’s training record in the validated tracking system or LMS during task scheduling. If employees have been trained on all the procedures listed in their curricula, the supervisor can make the task assignments.

What if the supervisor makes a mistake in checking the training records? What if the supervisor is not diligent, or overlooks a particular employee, or misses a page of the training record? Referring again to the Red Cross example, where the employee was not trained before touching the product, the Red Cross concluded that “the Education Coordinator failed to compare the employee’s previous training transcript with the training requirements.”18

Thereupon an organization might develop an even further SOP that requires periodic checks by the quality unit of a random sample of employees found in GMP areas at a given time, to ascertain if they are in fact qualified for their assigned job functions. We will refer to such a controlled document as an “Assignment Monitoring Procedure.” If discrepancies are found, the Assignment Monitoring Procedure would require the generation of a Notice of Event (NoE) to inform management that a deviation has occurred. That NoE would need to address both the impact on the batch, to the extent the untrained employee had touched the regulated product, and the supervisory error itself.

13.3.1 Problems with this approach

There are two major problems with this typical approach. First, this approach presupposes that employees’ training curricula and ITPs, listed in the tracking system, correctly and currently include the procedures that are relevant to the tasks to which the employees may be assigned. On the one hand, the curricula may not correctly reflect the procedures. How does a supervisor ensure that every single procedure that relates to this task, or this process – regardless of who the originator of the SOP may be – has been included in this curriculum? However, the curriculum may not reflect the current procedures. How does the supervisor ensure that the versioning up of each procedure has been the occasion for an update of the employee’s curriculum?

These are hardly trivial questions. Change control and change management are substantial problems in a regulated industry subject to pervasive and persistent technological development. As if that were not enough, procedures are versioned up to change a single word. Procedures are versioned up and then found to be misaligned with higher corporate policies and standards; then they are versioned up still further to restore the status quo ante and alignment. Procedures are versioned up, omitting key paragraphs; they are subsequently versioned up to re-insert the omitted paragraphs. Multiple procedures co-exist for similar functions, for example, gowning; these procedures are versioned up, one by one, by their disparate business owners independent of each other.

The remedy for the constant revision of procedures is a combination of making better business cases for proposed changes, and having more peer review of the documents in process. But that remedy will not resolve the supervisor’s dilemma of task assignment.

If the curriculum is either incorrect or not current, the supervisor cannot ensure the employee is adequately trained, no matter how diligently the training record is checked, no matter how carefully the Task Assignment Procedure is executed. The only way to ensure compliance in this case is by over-training, that is, by providing training to employees for whom the SOP may not be relevant. Of course, that is not cost-effective training.19

Moreover, over-training may result in employee resistance to training. Many times this occurs among high-performing individuals, say in a research institute, and presents special problems for organizational morale and productivity.

Second, assuming for just a moment that the curriculum is correct and current, this approach presupposes that recourse to a NoE is an adequate procedural response for supervisory error. Regulators typically find this unacceptable, because recourse to a NoE also requires a list of immediate and specific corrective actions that will be taken. As an example of the failure to meet this requirement, consider the FDA Warning Letter to Pharmaceutical Formulations, Inc. dated 5 May 2004: “Process failures resulting in the rejection of substantial quantities of drug products were not investigated and there is no documentation to show any corrective actions.”20

Returning to the first problem, it is crucial to recognize the misspecification of task responsibilities in the proposed Task Assignment Procedure. This procedure places the key responsibility on the supervisor for ensuring that employee training and qualification requirements are completed and documented, while not giving that supervisor necessary information about the accuracy and currency of the curricula, the status of procedure initiation, the status of procedure revision.

Instead, the Task Assignment Procedure should ensure that the originator (or business owner) of any new or revised SOP communicates with each impacted functional area to determine who the impacted employees are, that is, the training audience for the forthcoming SOP. This brings us to the third part of this chapter, where we propose an alternative approach to ensuring that the requisite training on the finalized module has occurred before the employee touches the regulated product.

13.4 The role of the target audience list

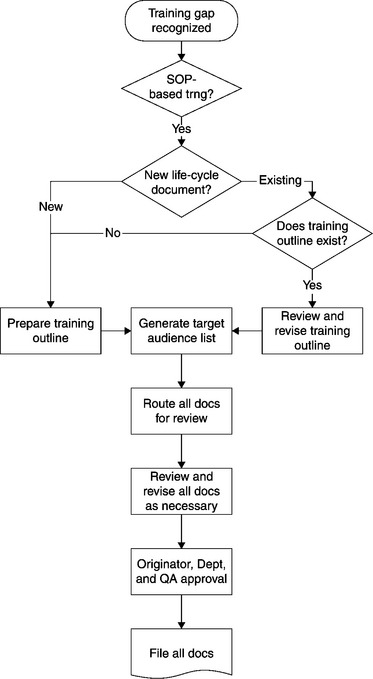

This part addresses four topics. First we will compare and contrast the purpose of a SOP with the purpose of training to a procedure. Next we will delineate the role of a Training Outline as a brief summary of the training implications of a new or revised SOP. Third, we will present a process map of the development and utilization of a Training Outline, and the associated Target Audience List. Fourth, we will discuss the use of the Target Audience List as the alternative approach to ensuring the requisite training occurs.

13.4.1 The purpose of a SOP

As already pointed out, a procedure lists the necessary steps (tasks) that, taken together, are sufficient to produce the desired process result. It can address several kinds of process – a person to machine process, a person to paper process, or a person to person process, or some combination of the three types. An SOP, typically in documentary form, indicates the sequence of tasks, the personnel or positions that are responsible for the tasks, and the standards that define the satisfactory completion of the tasks.21

13.4.2 The purpose of training to a procedure

Training is a person to person process that prepares each employee (the trainee) to successfully execute the steps (tasks) in a procedure, in the appropriate setting, stipulated order, mandated workgroup, and specified timeframe. Training is the combination of trainee(s), training materials, virtual or actual trainer, and the interaction of these elements.

Thus procedures and training are different. The procedure is a document, a controlled document subject to the quality unit’s approval. Training is an interactive process. Of course, a procedure can be the object of training, and training can be proceduralized. But the two are distinct; reading a procedure is not the same as being trained on that procedure;22 being trained on a procedure is not the same as being a subject matter expert on that process.

How do we align the procedure and its associated training? How do we provide the supervisor with necessary information about changes to relevant procedures so as to ensure that employee training and qualification are completed and documented?

13.4.3 The role of the training outline

As discussed in Chapter 5, a Training Outline is a controlled document that provides a brief summary of the training implications of a new or revised procedure. The Training Outline allows any employee to quickly ascertain critical dimensions of training associated with a particular SOP, including the behavioral objectives of the training, the training module’s fit in the larger curriculum, the delivery method, assessment materials, and of course the training audience.

When a performance gap or training gap is identified, management must decide on the appropriate CAPA to respond to the gap. There are two possibilities:

In either case, the associated training will require the development or revision of a Training Outline. The instructional designer (or originator of the procedure) will ask “Does a Training Outline exist?” If one already exists, the Training Outline will be reviewed and revised as necessary. If not, one will be prepared.

The instructional designer will review five points:

1. Does the SOP or other document contain background history or perspective of the process that would aid in the training?

2. Does the SOP or other document cover all related processes?

3. Does the SOP or other document thoroughly identify cGMP aspects?

4. Is all relevant training information covered in the Training Outline?

5. Will all facilitators present the training/information consistently?

In the case of non-life-cycle documents and GMP regulatory training, the instructional designer can ask management about the range of the training audience; usually it will straightforwardly be all employees, all managers, etc.

We display here a process map of the development and utilization of a Training Outline, and the associated Target Audience List, for the case of a life-cycle document (Figure 13.1). This will be followed by a brief discussion of the Target Audience List.

13.4.4 Developing and utilizing the Target Audience List

In the case of a life-cycle document, the instructional designer will review the SOP Scope Statement as well as the Task Responsibilities, and generate a provisional Target Audience List. This is the problematic case. These are the employees who must be trained to the new or revised SOP, based on the finalized training module, before they touch the regulated product.

The instructional designer will then attach the Training Outline, and the associated (provisional) Target Audience List to the procedure’s Change Request. When the procedure and its Training Outline are circulated for review and approval, the Target Audience List will be circulated as well. Management of each unit impacted by the procedure will review the list and recommend limiting it or expanding it, based on their direct responsibility for the task assignments of the listed employees.

The instructional designer will then take those recommendations into account as the procedure, Training Outline, and Target Audience List are reviewed and approved. Moreover, management in the impacted units are alerted for the approval and implementation dates of the SOP, and can accordingly schedule personnel for necessary training on the finalized module.

After the new or revised SOP has been approved, there is a “training window” before the procedure goes into effect, a time period within which the impacted employees can be trained to the SOP. This window is typically a week or two in length. It is critical that the training audience be defined before that window opens, hence before the SOP is approved, so that all training on the finalized module will be completed before the implementation date.23 Thus, the risk of untrained personnel touching the regulated product will be minimized.

13.5 Conclusion

This chapter had three parts. We first reviewed the scope and impact of the FDA regulations of pharmaceutical manufacturing in general, and of training in particular, and found them to be comprehensive. Any person who touches the regulated product, or who supervises that person, falls within the scope of the regulations. These regulations impact on these persons via written SOPs that provide comprehensive guidance for drug manufacturing. These persons must be trained on these procedures insofar as they relate to the employee’s functions prior to their touching the regulated product. Hence, the importance of ensuring that the final implementation of the training module includes all these employees.

Next we considered a typical organizational response to the need to ensure employees are trained before touching the regulated product. This takes the form of a procedure requiring that the supervisor ensures all necessary training and qualification requirements in the employee curricula are completed and documented prior to assigning an employee to a task. We pointed out several problems with this approach, especially the failure to provide the supervisor with necessary information about the accuracy and currency of the employee curricula.

Finally, we presented an alternative response whereby the Training Outline, a controlled document including a Target Audience List, is employed by the originator of a new or revised procedure to communicate with each impacted functional area to determine which employees require training. Those employees’ curricula are revised to correspond to the new or revised procedure, ensuring they are trained on the finalized module before touching the regulated product.

13.7 References

Beauchemin, K., et al. ‘Read and understand’ vs ‘a competency-based approach’ to designing, evaluating, and validating SOP training. PDA J. Pharma. Sci. Tech.. 2001; 55(1):10–15.

Bohte, J., Meier, K. Goal displacement: assessing the motivation for organizational cheating. Publ. Admin. Rev.. 2000; 60(2):173–182.

Bringslimark, V. If training is so easy, why isn’t everyone in compliance? Biopharm Intern.. 2004; 17(1):46–53.

DiLollo, J. The use of SOPs in a pharmaceutical manufacturing environment. J. cGMP Comp.. 2000; 4(3):33–35.

Fuller, N., FDA Fines City Red Cross in Training Irregularity. Baltimore Sun, 2006. [2 August.].

Gallup, D., et al. Selecting a training documentation/ record-keeping system in a pharmaceutical manufacturing environment. PDA J. Pharma. Sci. Tech.. 2003; 57(1):49–55.

Jones, M. Just-in-time training. Adv. Devel. HR.. 2001; 3(4):480–487.

Lindemann, P. Maintaining FDA compliance in today’s pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities. presented at the PharmTech Annual Event, Somerset, NJ, 13 June, 2006:15.

Merton, R.K. Social Theory and Social Structure. Glencoe, IL: Free Press; 1957.

Mosher, B. E-Reference: the real just-in-time training. Chief Learn. Off. Mag. 4(11), 2005.

Swartz, M., Krull, I. Training and cdompliance. LC • GC North America [Liquid Chromatography – Gas Chromatography]. 2004; 22(9):906–912.

Vesper, J. Defining your GMP training program with a training procedure. BioPharm.. 2000; 13(11):28–32.

Vesper, J. Performance: The goal of training – or why training is not always the answer. BioPharm.. 2001; 14(2):44–46.

Watson, C., Temkin, S. Just-in-time teaching: balancing the competing demands of corporate America and academe in the delivery of management education. J. Man. Educ.. 2000; 24(6):763–778.

1See Carol Watson and Sanford Temkin (2000); Michael Jones (2001); and Bob Mosher (2005).

2See 21 CFR 211.25, “Personnel qualifications.”

3Available from: www.fda.gov/foi/warning_letters/archive/g5395d.pdf

4Available from: www.fda.gov/foi/warning_letters/archive/g6159d.pdf

5For biopharm personnel, 21 CFR 600.10; for non-clinical lab personnel, 21 CFR 58.29; for medical device personnel, 21 CFR 820.25; for human tissue recovery personnel, 21 CFR 1271.170.

6Available from: www.fda.gov/foi/warning.htm

7Cited in “Production Procedure, QC Unit Citations Top FDA-483 List,” Gold Sheet, Vol. 38, No. 5 (2004), pp. 3–4. For FDA inspections conducted from 2001 to 2003, inadequacy of training was the seventh most cited observation, with 173 observations out of a total of 1933.

8See the FDA Warning Letter dated 24 June 2005 to Greer Laboratories, Inc. Available from: www.fda.gov/foi/warning_letters/archive/g5395d.pdf

9See John Levchuk (1990).

10See David Gallup et al. (2003), esp. pp. 49–50 for an insightful discussion of FDA requirements for training documentation; also Vivian Bringslimark (2004), esp. pp. 51–52.

11See James Vesper (2001), esp. p. 44.

12Available from: www.fda.gov/ora/frequent/letters/ARC_20060727_ADLetter.pdf. See also Nicole Fuller (2006).

13See Robert Merton (1957); also John Bohte and Kenneth Meier (2000).

14See Philip Lindemann (2006).

15As Levchuk, op. cit. has commented, however, “usually, available information is inadequate to establish a specific reason beyond failure to have a training program, failure to follow the written training program, or failure to ensure that personnel received training.”

16See Levchuk, op. cit.

17See also Vesper (2001), op. cit., p. 46.

18Available from: www.fda.gov/ora/frequent/letters/ARC_20060727_ADLetter.pdf

19This is obvious for skill training; as Michael Swartz and Ira Krull (2004), esp. p. 906, have expressed it for training in cGMP regulations: “It is of little value to train or educate an employee on all of the regulations if there is no impact on the job that person ful fills every day.”

20Available from: www.fda.gov/foi/warning_letters/archive/g4683d.pdf

21See John DiLollo (2000).

22As Katherine Beauchemin et al. (2001), esp. p. 11, have accurately put it, “Clearly the ‘read and understand’method does not meet the criteria set out for validity and reliability;” see also Bringslimark (2004), op. cit., p 46.

23See James Vesper (2000), esp. p. 29.