Chapter 10

Keeping Your Flock Happy and Healthy

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Providing biosecurity for your flock

Providing biosecurity for your flock

![]() Keeping your birds calm and collected

Keeping your birds calm and collected

![]() Grooming your chickens

Grooming your chickens

![]() Managing temperature extremes

Managing temperature extremes

The art of handling and managing animals is called animal husbandry. Caring for animals goes beyond knowing how to house them and feed them — it also involves knowing how to manage them so that they’re healthy and content.

In this chapter, we discuss how to keep your flock healthy with preventive care and how to humanely handle chickens. In the next chapter, we discuss what to do if your chickens do get sick.

Providing Biosecurity for Your Flock

If you ever have the chance to visit a large poultry operation or a poultry research station, you’ll be amazed by the precautions it takes to prevent disease or parasites from entering the flock. You’ll have to wear special coveralls, plastic booties, and maybe a face mask just to walk inside a facility — and maybe even to get on the grounds. Biosecurity, as defined by the Environmental Protection Agency, is the protection of agricultural animals from any type of infectious agent — viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic.

As the owner of a small flock or a pet chicken, you don’t have to take all the extreme biosecurity measures large operations do, but if you want healthy chickens and you want to keep your family healthy, some biosecurity measures are necessary.

Maintaining biosecurity

Home flock owners often wonder how their chickens became ill, especially if they don’t take them to shows and sales. Studies have shown that 90 percent of diseases are carried to chickens by human caretakers. Disease organisms can survive on shoes, clothing, unwashed hands, car tires, and equipment. Keep that info in mind when you’re visiting a poultry show or your friend’s flock.

Follow some basic biosecurity guidelines for your flock’s safety:

- If you’ve been visiting other flocks, at the very least, wash your hands before caring for your own birds. To go the extra mile, also change your shoes and clothing.

- Be very careful about who you allow to handle your birds. Sometimes you may need to ask someone to help you with your birds, but do this selectively and infrequently. Home flock owners like to visit and handle the chickens, but sharing birds is an excellent way to spread disease. Share photos instead.

- If poultry diseases break out in your area, avoid going places where poultry reside. If you do come in contact with them, take a shower and put on clean clothes and shoes before you take care of your flock.

- If you lend poultry equipment, cages, carriers, and so on, or if you buy used equipment, be sure to thoroughly disinfect it before you use it on your own birds or even store it on your premises.

- If at all possible, maintain a closed flock — don’t add new birds to existing flocks. (Chicks that come from a reputable hatchery and that you raise in a brooder are an exception.) If you do add new birds, quarantine them for at least 30 days far away from your flock. Any bird that leaves your premises and is around other birds needs to be quarantined if it returns to the flock. We talk more about quarantines later in this chapter.

- Try to minimize your flock’s contact with wild birds. Wild birds can carry many diseases, including strains of avian flu, to your flock. Don’t let wild birds nest in or on shelters, and keep them out of chicken feed dishes. Don’t mingle wild orphans such as baby ducks with your flock.

- Eliminate mice, rats, and insect pests like cockroaches from your coop because they can spread diseases. Try to control flies and mosquitoes.

- If many birds die within a 48-hour time period or less and you don’t see any signs of a predator attack, contact your state veterinarian. (To find your state veterinarian, contact your state Department of Agriculture.) Describe any symptoms and follow their directions.

Knowing when to quarantine chickens

Every time you add birds to your flock, you increase the risk of introducing disease and parasites. One of the best ways to protect your flock is to quarantine all new birds or birds that have been to shows or have been off the property for some reason. Small flock owners are the least likely to do this, but if you frequently show birds or you add new birds often, sooner or later, you’ll have a problem if you don’t use a quarantine system.

To quarantine, you need a large cage or other area away from your flock where you can keep all new birds (or birds that have been to shows) for 30 days. The quarantine area needs to be at least 30 feet from your other birds, but more distance is even better. Feed and care for the birds in quarantine after you have fed and cared for the regular flock. Watch the birds for signs of illness, and examine them for lice and other parasites. If all is well in 30 days, you can add them to the flock.

You also want to put quarantine in effect whenever you suspect a bird is ill or whenever a chicken is injured. Quarantine prevents diseases from spreading and protects chickens who aren’t feeling well from bullying and even cannibalism by flock mates. It also allows you to alter the environment, such as by adding heat, and allows you to monitor whether the bird is eating and drinking and see what its poop and/or eggs look like.

If more than one bird seems to be ill with the same symptoms, it’s fine to quarantine them together. Feed and care for sick chickens after you’ve cared for healthy ones, and wash your hands after caring for sick birds. Since some chicken diseases can sicken people, too, don’t eat, drink, or smoke when caring for sick chickens. It might be best to keep children and anyone with a compromised immune system away from sick chickens. It’s not also a good idea to bring sick chickens into your home.

If sick chickens seem to recover, give them several days more in quarantine before you return them to the flock. When you return them, watch to make sure they aren’t picked on. The absence of one or more birds may have changed the pecking order, and fighting may begin. Read the section “Introducing new birds carefully,” later in this chapter, for tips. To your other chickens, a bird that has been absent for a while is a new bird.

Keeping Disease and Parasites Away

Following some basic biosecurity measures as outlined earlier in the chapter helps keep your flock healthy. Vaccination also can prevent some chicken diseases. Other diseases result from parasites, which owners can take steps to control as well. In this section, we discuss these preventive measures.

Giving vaccinations

Just as you have your pets vaccinated for rabies and other diseases, you need to give your chickens some vaccinations, too. Vaccines aren’t available to prevent every disease that can affect chickens, so you still must practice good management techniques to stave off disease problems. But preventing diseases with vaccination when you can is a good idea.

Some diseases are more prevalent in one area than another. Ask a local veterinarian or a poultry expert from your county Extension office (go to www.csrees.usda.gov/Extension/) about which vaccinations chickens in your area need. Home flock owners may decide to do without vaccinating their chickens and live with the risk. Only you, as the owner, can make that decision. If you never show chickens and you don’t frequently buy or sell chickens, you may never have a problem. If you intend to sell live chickens, breed them, or show them, however, you need to get the vaccines recommended for your area.

Some vaccinations are for chicks, and some work only for older birds. If you don’t mind giving vaccinations, you can usually buy the vaccines from poultry supply places. Follow the label directions exactly for administering and storing the vaccines. If you’d rather not tackle the task yourself, contact a veterinarian or ask an experienced chicken-keeper to help.

Following is a list of common diseases that chickens can be vaccinated against:

- Fowl pox causes sores and respiratory problems, and some birds die as a result. In areas where fowl pox has been a problem, chickens need to be vaccinated. The vaccine is given at hatching and again at 8 weeks or at 10 to 12 weeks. The vaccine is usually administered with a special device that’s dipped in the vaccine and then stuck into the wing web.

- Infectious coryza, avian encephalomyelitis (AE), Newcastle disease, Mycoplasma gallisepticum, avian flu, and fowl cholera are serious diseases that cause poultry death for which vaccines are available. However, the vaccines need to be given only when outbreaks arise in your area. Your vet or county Extension office will be able to guide you if an outbreak develops in your area. Sometimes the state agriculture department coordinates vaccinations when outbreaks occur.

- Infectious laryngotracheitis is a viral disease similar to pneumonia in humans. The death rate is high in infected chickens, and birds that recover are carriers for life and can infect healthy chickens. If you’re showing chickens or you regularly buy and sell chickens, you need to vaccinate your flock for infectious laryngotracheitis once a year. Use only tissue culture origin (TCO) vaccines in home flocks. The vaccine is given as an eye drop, so it’s easy to give.

- Marek’s disease causes tumors and death in young birds. Almost all hatcheries offer to vaccinate chicks for Marek’s disease for a small fee, and it’s a good idea for small flock owners. We highly recommend that every chicken get this vaccination. If you hatch birds, you can vaccinate them yourself. The vaccination is given by needle just under the skin. It’s only given once. After 16 weeks of age, the vaccine isn’t needed.

Putting up barriers against parasites

Worms and other internal parasites are common in chickens, and at some point, most chicken owners have to deal with them. In the next chapter, we go into more detail about diagnosing and treating both internal and external parasites. However, preventing parasites is always preferable to trying to treat them after the chickens get them, so in this chapter, we discuss prevention.

A parasite uses your chicken for food. Two basic types of parasites prey on them: internal and external. Internal parasites, which include worms, coccidia, and a few other tiny creatures, feed inside the chicken in various places. External parasites feed on the outside of your chickens. They may live right on the chicken or just feed on them and hop off to hide. The most common external parasites are lice and mites, but others exist.

Preventing internal parasites

If you allow your chickens access to the ground, you will almost certainly have some internal parasites at some point. But that’s not a good reason to prevent your chickens from enjoying the outside. Most flocks that are well fed and healthy don’t show any signs of a mild parasite infection or have any effects from one.

There are two types of internal parasites to be concerned about in chickens: worms and coccidia. Chickens get several types of worms, but three are the most common: large roundworms, tapeworms, and gape worms. Different than a worm, coccidia are small parasites that infect chickens’ intestinal tracts and can cause death in young chicks. We discuss how worms and coccidia affect the health of chickens in more detail in Chapter 11.

Internal parasites are picked up from the feces of other chickens or wild birds and from the soil. They can also come from chickens eating earthworms and other bugs as they roam your yard. These larger critters may host one stage of the worm or other parasite, and then the parasite finishes its life cycle in your chicken.

To reduce worm populations, try to move pastured poultry or chickens in small tractor-type cages every few days to new ground that has been without chickens for several months. This rotation helps prevent worm eggs from building up in the soil.

It’s also a good idea to worm all new birds during their quarantine if they’re at least 18 weeks old or when they reach 18 weeks of age. For existing flocks, we don’t recommend regular preventative worming. Give worm medications only when worms are diagnosed and seem to be causing health problems.

Giving all chicks a good start by treating for coccidia early is highly recommended. Coccidiostats, medications that kill coccidia, can be given as medicated starter feed or in the water and don’t require a prescription. They include medications such as Amprolium (Amprol, Corid) and Decoquinate (Deccox), and you can find them in feed stores and poultry supply catalogs. As chickens get older, they may still carry the parasite, but most develop immunity to its effects and generally don’t need treatment.

For more information on internal parasites and their treatment, see Chapter 11.

Keeping external parasites away

External parasites, including mites, lice, ticks, and other creepy crawlies, are also fairly common in chickens. It’s important to keep both external pests and internal parasites from getting to your chickens. They make your chickens uncomfortable and also make people very unsettled if they know the chickens have them, even if most of these pests can’t infect humans. (We get itching just thinking about them.)

External parasites get to your flock from new birds added to the flock, infested equipment and housing, wild birds, or rodent pests.

To prevent external parasites from entering your flock through new chickens, closely examine all new chickens you get. Part the feathers and look for crawling creatures. The bugs may actually crawl on you, making spotting them easy. Check around the vent (under the tail). If the feathers around the vent look like they have dirt deposits near the skin, the birds may have mites. A good practice is to treat all new chickens with a product to control lice and mites while they’re in quarantine. See Chapter 11 for suggestions on those products.

If you purchase used housing, cages, carriers, and other equipment, they may be carrying unwanted guests. Some chicken mites, ticks, and bedbugs don’t stay on the birds all the time, but hide in the cracks of housing and equipment. Examine and then thoroughly clean and disinfect all used housing and equipment. Some external parasites can remain in used housing or equipment for more than a year and still be ready to attack your birds. You’ll want to treat used housing with pesticides before you add your chickens, and be sure to thoroughly disinfect used equipment as well. Use a pesticide approved for poultry, not a garden or household pesticide or one for pets. Read Chapter 11 for pesticide recommendations.

To prevent external parasites, also remove wild bird nests, both old and new, from chicken housing and try to restrict wild birds from eating and roosting in your coop. Put screens on chicken house windows and fix holes where they can enter. If you free-range your chickens, you can’t stop them from occasionally coming into contact with wild birds, but don’t encourage contact by feeding birds like wild turkeys and ducks close to chicken areas. Also keep your chickens out of wild song bird feeders.

To prevent external parasites from hitching a ride into your coop on rodents, you will need to control the rodent population in and around your coop. Read Chapter 9 to learn ways to prevent and control rodent pests.

Learning about chickens and human health

In addition to diseases that affect your chickens’ health, some bird diseases regularly turn up in the news as being harmful to humans. Unfortunately, these news stories scare people into believing that keeping chickens is dangerous. We’re here to assure you that your risk of catching any disease from chickens is minimal. In fact, you put yourself at greater risk of contracting a disease by going to work than by keeping chickens.

However, in rare cases, humans can get some diseases and parasites from contact with chickens. We want to mention them here so you can take the proper precautions to keep you and your family healthy.

What diseases can people get from chickens?

Campylobacteriosis, salmonellosis, and E. coli are the most common diseases people can get from coming into contact with chicken poop or eating undercooked eggs and poultry meat. In most cases, these diseases cause an intestinal flu–like illness and most people recover. But small children, the elderly, and people with compromised immune systems can get very sick and even die from these bacteria. In rare instances, humans can also get psittacosis, abacterial disease, from chickens. The viruses, avian flu, avian tuberculosis, Newcastle disease, and ersipeloid, can occasionally infect humans. These diseases are no longer common in domestic birds and require close contact with poultry in order for people to get the disease.

People can also get histoplasmosis and farmer’s lung, which are caused by irritation to the lungs from feather dander, dust, and contaminated soil, complicated by an allergic reaction of the body’s immune system.

Can the same parasites that affect my chickens affect me?

Some parasites that live off chickens can move on to humans. External parasites people can get from chickens include the chicken mite Dermanyssus gallinae, chiggers, bedbugs, bat bugs, and ringworm. Lice from chickens may get on humans and even bite them, but they don’t live on humans long. Bed bugs and bat bugs are similar, but they don’t live on either people or chickens; they just come out at night and feed on them.

People don’t get the same internal parasites as chickens, so that’s one problem you don’t need to worry about.

Sensible safety rules

Of course, you always want to follow safe, sensible methods of handling and caring for chickens. These methods include the following:

- Don’t keep chickens in the house, even with diapers. Although chickens make excellent pets when kept outside, your chances of getting sick from your chickens increases greatly if you share your living space. Chicken feet carry bacteria like E. coli, salmonella and Campylobacteria and deposit them around the house. Avian Tuberculosis and avian flu are easier to acquire when there is close contact on a frequent basis with an infected chicken.

- Wash your hands carefully after handling and caring for chickens.

- Keep chickens away from your face — no kissing or nuzzling.

- Wear disposable gloves when handling sick or dead chickens. Also wear gloves when you come in contact with chicken poop.

- Wear a face mask. Keep from inhaling dust when cleaning coops.

- Cook chicken meat and eggs thoroughly and store them properly.

If you let your chickens roam freely through your yard and garden, thoroughly wash vegetables and fruits that may have become contaminated by chicken droppings. Also clean patio and picnic tables and railings chickens have soiled before you use them.

If you let your chickens roam freely through your yard and garden, thoroughly wash vegetables and fruits that may have become contaminated by chicken droppings. Also clean patio and picnic tables and railings chickens have soiled before you use them.- Quarantine sick chickens. See the section “Knowing when to quarantine chickens” earlier in this chapter for more info.

Supervise children when they’re handling chickens, eggs, or poultry equipment, and make them wash their hands immediately and thoroughly — not just splash them with water — when they’re done. Don’t let toddlers teethe on the shelter door handle while you collect eggs or kiss chicks for a cute photo.

Controlling Environmental Conditions

Many more chickens die each year from poor environmental conditions than from disease. In the housing chapters, we talk about designing housing to protect chickens from environmental problems such as dampness, heat, and cold. Disease problems often begin when poor conditions stress the birds’ immune systems, so good environmental conditions are important in maintaining the health of your flock.

Dealing with heat, cold, and dampness

The temperature and the amount of moisture in your chickens’ environment have a significant impact on their wellness. Chickens need protection from extreme heat and cold, and you must keep their environment dry. The following sections address these concerns.

Handling the heat

When the temperature rises above 85 degrees Fahrenheit, especially when the humidity is high, it’s time to check on the chickens. If your birds are subjected to heat stress for too long, they’ll die. For meat birds, death can occur within a few hours in heat above 90 degrees, especially with high humidity. Losses can start occurring rapidly — within hours — if temperatures rise above 100 degrees Fahrenheit for any type of chickens.

Chickens that are too hot are inactive and breathe with their mouths open. If your birds appear heat stressed, work slowly and calmly with them. Any more stress from fright may cause death.

Free-ranging chickens survive heat much better than penned birds because they instinctively find the coolest places. Heavy birds like the broiler hybrids suffer greatly in the heat. They may not eat enough and thus won’t gain weight as quickly as cooler birds.

You can improve the conditions of penned birds by shading them, putting a fan in the shelter, or putting a sprinkler on the shelter roof. The wet roof cools the coop when water evaporates from it. Chickens don’t like to drink warm water, so move their water dishes to the coolest areas, change the water frequently, and make sure water is always available.

If you see chickens that appear very stressed from heat and you can easily pick them up, immerse them in cool — but not cold — water for a few minutes.

Fighting off the cold

Chickens actually handle cold better than heat, as long as their shelter is dry and out of the wind. But frostbite of the combs, wattles, and toes may occur when temperatures get down near 0 degrees Fahrenheit. Frostbite causes blackened areas that may eventually fall off. If you live in a cold-weather area, try to pick breeds of chickens that have small combs and wattles because those parts lose less body heat and don’t get frostbitten as easily.

Having wide roosts is a good idea because they allow chickens to sit with their feet flat instead of curling their toes around the roost. When chickens sit with their feet flat, their feathers cover the toes, which makes the toes less susceptible to frostbite.

In addition to causing frostbite, cold temperatures can cause hens to stop laying, or if they continue to lay, cold weather may contribute to egg binding (see Chapter 11 for more info on egg binding and other health problems).

Chickens need more feed in cold weather to keep their bodies functioning properly. Water is also important. You must either provide a heated water dish or furnish water twice a day. If chickens don’t drink, they won’t eat as much, and if they don’t eat as much, they’re more susceptible to dying from the cold.

To make chickens more comfortable, you may decide to heat the coop. If you do, don’t heat it to more than 40 degrees Fahrenheit. More than that usually causes problems with dampness. For more about coop heating, see Chapter 6.

Doing away with dampness

Environmental conditions that are damp or wet are big contributors to illness in chickens. Damp conditions can come from moisture produced by birds’ respiration and droppings in poorly ventilated housing, or from rain or snow. The warmer the air becomes, the more moisture it holds. Heating a coop too much in cold weather often results in the formation of condensation, which causes wet, unhealthy conditions.

Wet areas favor the growth of molds and fungus and cause additional discomfort in hot weather. Molds on feed and bedding cause a wide variety of illnesses, and they aren’t good for the human caretaker, either. High humidity makes ideal conditions for many respiratory diseases. Always keep chicken bedding dry, and never give your birds moldy feed. Make sure housing is well ventilated. Keep outside runs well drained to prevent chickens from tracking in a lot of moisture on their feet.

Keeping your chickens from eating poisons

As with all livestock, the best approach with chickens is to anticipate problems before they occur and prevent them from happening. Chickens aren’t particularly discriminating about what they eat, and although you wouldn’t purposely feed your chickens poisonous substances, you may not realize what chickens view as food. Following is a list of some commonly overlooked dangers:

- Garden seeds that are treated with fungicides or other pesticides: If you use these types of seeds, make sure your chickens can’t scratch them up and eat them or get to them in storage.

Granular fertilizers: If a chicken happens upon some widely scattered bits of fertilizer, it may sample one or two and then move on. But if chickens see you scattering fertilizer, they may come running and, in the spirit of competition, gobble up quite a bit before either they quit or you chase them off.

Keep all fertilizers and pesticides in places where chickens can’t get to them and where children can’t find them and feed them to your chickens. Lock up the chickens before you spread fertilizer, or make sure they aren’t nearby to watch you do it.

Paint: Watch out if you’re scraping paint off old houses or buildings and the flakes fall into the soil. If the paint is lead based and the chickens eat the pieces — either purposefully or when eating food — you may have a problem. Lead poisoning is generally slow, and sometimes it’s hard to connect the illness with the lead paint chips.

Speaking of paint, when the time comes to apply a new coat, don’t go away and leave that can of paint open next to the chicken shelter.

- Pesticides: Keep chickens out of any areas to which you’ve applied pesticides to kill weeds or bugs. Just getting some pesticides on their feet may be enough to harm your birds. Snail and slug baits are often in pellet form, and they’re extremely toxic.

- Rodent poisons: Mouse and rat poisons are deadly to chickens if they ingest them. Chickens shouldn’t eat mice and rats that have been poisoned, either. Be very careful in placing mouse and rat baits. Chickens are curious birds, and they may reach their heads under things and in holes to sample what they see.

Free-ranging chickens generally have a good sense of what’s poisonous to eat as far as berries and vegetation go. Penned-up chickens are more likely to eat “food” that’s not safe because they’re hungrier for variety and fresh food.

Safely Handling Your Flock

Knowing how to correctly handle chickens is important because it reduces stress on your flock and on you. Handling involves catching chickens, carrying and holding chickens, and, to some extent, taming them. To a new chicken-keeper, handling chickens can seem frustrating or even frightening at times, but don’t worry — you’ll improve with experience.

Catching chickens

To care for your chickens, sometimes you have to catch and hold them, but how do you catch a bird in your pen at home? If you can, wait until night and then walk in and take it off the roost. If you normally leave a night light on in the shelter, mark in your mind where the bird is, turn off the light for 10 minutes, and then go in with a flashlight to get it. Try not to disturb the other birds, especially if you need to catch more than one.

If you need to catch a bird and you don’t have time to wait until night, lure it into the smallest area possible (usually the shelter) and block off any exits. Then go in calmly and slowly, and try to grab for the legs. Birds expect to be grabbed from overhead, so going beneath them to get the legs surprises them. Don’t grab birds by the neck unless you’re going to be butchering them anyway.

You can also use a net or a catching stick, but in our experience, nets spook birds and don’t work much better than hands in close quarters. Nets are better for open areas. A catching stick has a hook at one end that you push beyond the bird’s feet and then slide back, hopefully snagging the feet and pulling the bird toward you. You may need a little practice to figure out how to use one.

To catch a chick that’s in a brooder, try putting one hand in front of the chick and using the other hand to sweep the chick into it. Don’t pick up a little chick by its legs; scoop up the whole body. Putting your hand down over the back scares chicks because the motion resembles a predator swooping down, but sometimes doing so is the only way to catch them.

When a chicken actually flies the coop, new chicken owners often panic. Although chickens may take every opportunity to escape, they usually don’t go far unless they’re scared and in a strange place. If a chicken gets out of a pen at your home, don’t be alarmed. Unless it’s chased, it will generally hang around close to any remaining penned birds.

Even if the whole flock gets out, there’s no reason to panic. First, go look at the pen and see how they got out. Fix the problem before you try to get them back inside.

Chasing chickens is your last resort — they’re faster than you, so try other options first. If you have a special bucket you use to feed them or bring them treats, get it out, add some feed or treats, and show it to them. If they seem interested, lure them back to their pen, throw the treats inside an open door, and shut it when they’re inside. If they won’t go in the pen, you may be able to trick them into a garage, shed, or fenced yard that you can close up after them.

Most chickens want to go back to the familiar place where they roost at night when it starts getting dark. After the other chickens have settled down on the roosts, open the door or gate, and they’ll often pop right in. If you can’t catch a chicken by nightfall, watch from a distance to see where it goes to roost for the night. When it’s completely dark, you can take a flashlight and simply go pick it up — if you can reach it.

What happens if the chicken escapes in an unfamiliar place, such as at a show? If you can, let it settle down a bit. Don’t chase it out of the area. People who travel with chickens to shows or sales need to have a long-handled net or a catching stick with them.

Before you try to use a net or a catching stick, however, throw down some choice grain like corn to divert the chicken’s attention. Or wait until it’s attracted to someone else’s caged birds, is crowing, or is otherwise engaged before you attempt to catch it. If conditions are crowded and catching the bird seems impossible, try coming back after the crowd has left.

If you have a really hard-to-catch chicken running loose, the old trap with a box and string or a live trap may work. Fortunately, chickens seem to get easier to catch the older they get, especially if their caretakers are kind to them.

Carrying and holding chickens

Carrying birds by the legs with the head hanging down is okay for birds you’re taking to slaughter, but don’t do it with your prize layers or pet birds. You can dislocate the legs or otherwise hurt them. Instead, tuck the bird under one arm with your other hand holding both feet, or cradle the bird in your arms with the wings under an arm. A firm squeeze and soothing talk soon calms most birds. The head can face forward or back, whichever works best for you.

If you need to restrain a bird for treatment and you don’t have anyone to help you, you may need to tie the bird’s legs together and lay it on a table while restraining the wings with one hand or loosely wrapping the bird in a towel to restrain the wings. Some people learn to hold the chicken with their knees while seated, with the feet up and the head facing away from them.

Don’t squeeze birds too hard when carrying them or restraining them for treatment. A chicken needs to move its ribs to breathe well, and even if the mouth and nose are uncovered, you can suffocate a bird if you hold it too tightly. Suffocation often happens when children hold baby chicks too tightly. A chick needs to be held loosely in your closed hand, with its head peeking through your fingers.

If a bird is really wild and fighting, you can cover its head loosely with a hood or a piece of soft cloth, and it will probably settle right down. Don’t try to carry too many birds at a time — take your time to do it right and humanely. Beware of roosters with long spurs on their legs. When they’re struggling, the spurs can scratch your arms quite badly. Wear long sleeves to handle these birds.

Taming chickens

Chickens have become popular as backyard pets as well as food producers. But as a pet, chickens do have some drawbacks. With a few exceptions, chickens never grow to like cuddling or being held. As mentioned earlier, chickens are prey animals, and anytime something bigger than them catches and holds them, it’s stressful. If the kids want a pet they can dress up or sleep with, chickens aren’t a good choice.

Many chickens can learn to eat out of your hand or even jump on your knee if you’re sitting quietly. You can even train chickens to do tricks by using treats. They may let you gently stroke them occasionally. But they don’t like being grabbed or touched, for the most part. They may follow a kind keeper around the yard or garden and provide hours of enjoyment as you watch their antics. But chicken chasing isn’t not fun for them — it’s sheer terror.

Some breeds are calmer than others, and individual chickens have different personalities. The tamest breeds are generally production-type birds that lay brown eggs: Isa Browns, Rhode Island Reds, Wellsummers, and so on. These birds were selected for calm behavior over the years because calm birds are better layers. The brown egg color also seems to be linked genetically to calmer, quieter dispositions. Polish, Silkies, Brahmas, and Cochins are also considered to be calm breeds. Some strains of Ameraucana and Easter Eggers are quite tame; others are not. Chickens of other breeds also may be calm and prone to taming as well.

Some people think they should handle baby chicks frequently to make the chickens more tame when they’re older, but this generally doesn’t work well. Chicks that are handled frequently often don’t grow as well as ones that aren’t handled and are more likely to get sick. And in most cases, they won’t be any tamer when they’re out of the brooder and have more room to escape from you than ones that you didn’t handle.

Routines do much for taming chickens, even older ones. Feed and water at the same times each day. People who are calm and quiet, who don’t rush around, and who seem predictable feel safe to the chickens, so they respond more calmly. Providing small amounts of treats also makes chickens happy to see you. Chickens do recognize the person who feeds and cares for them, and they also remember people who scare or harm them.

We’ve found that chickens mellow as they age, as long as they’ve been treated kindly. Be patient. Young hens are more distrustful and “flighty,” but experience will teach them that you can be trusted — or that they can easily outrun or fool you. As they age, they’ll become much less frightened of you — and maybe too friendly, in some cases.

Diffusing Stress

Stress affects all animals. Stress lowers the immune system response to disease and causes many undesirable behaviors. In this section, we discuss factors that may cause stress to your chickens and some ways to manage chickens to reduce that stress.

Managing the molt

Molting is the gradual replacement of feathers over a 4- to 8-week period. It’s a natural process, not a disease. Chickens generally act normally during molt. If they seem sick or don’t eat or drink well, something else is wrong. Molt is also a time for the hen’s reproductive system to rest. It usually happens in the fall as the days get shorter, but lack of food or normal lighting can also cause it. Even when hens are kept under artificial lights, molting eventually happens, usually after about a year of laying. Both hens and roosters molt.

Chickens begin to lose the large primary wing feathers and the head feathers first. From there, the process spreads backward gradually. Chickens may look a little scruffy during this time, but they shouldn’t look bald. You may notice a lot of tightly rolled pin feathers, which look like quills sticking out of the chicken, and a lot of feathers on the floor. The pin feathers gradually open into new, shiny, clean feathers.

Some breeds, particularly high-producing egg strains, have a quick, barely noticeable molt because they’re selected to get through molt quickly. Individual variability also comes up in the length of molt. Hens that complete molt quickly are generally the most productive and healthiest hens in the flock.

The process of molting and growing new feathers is energy intensive. Chickens with a proper diet and few parasites have little trouble with molt. However, molting is a time when you need to make sure your birds’ diet includes good-quality protein. Some people switch from layer ration to meat bird ration for a few weeks during molt because it has a higher protein ratio. You don’t need to add medications, vitamins, or anything else if you’re feeding a good commercial diet.

Because the immune system may be less active during molt, it’s best to avoid bringing in new birds or taking birds to shows during this time. Hens generally quit laying during molt, although some lay sporadically. Both of these situations are normal. The hen’s system needs to produce new feathers, not eggs. It’s an egg vacation. The first eggs she lays when returning to production may be smaller than normal, but she likely will quickly return to laying normal-size eggs.

Introducing new birds carefully

You want to limit new introductions to your chicken flock for two good reasons. First, you risk introducing disease to your existing flock (see the earlier section “Knowing when to quarantine your chickens” for advice on how to avoid that calamity). Second, you introduce stress because all chicken flocks have a ranking system, or pecking order. (We discuss basic chicken behavior in more detail in Chapter 2.) Every time you add or remove a bird, the order changes, causing fighting and disorder in the flock.

Unless a chicken has been alone and is pining for friends, it generally doesn’t like new birds and may viciously attack newcomers. Before a new ranking order is established and the new birds become part of the flock, you may witness bloodshed or even death. However, you can keep order with some strategies.

First, never introduce a new rooster into a flock with an established rooster. One or both of the birds may die in this case. If you want to breed a new rooster with your hens, you need to either divide the housing, runs, and ladies or remove the old rooster. A very young rooster that grows up with the flock sometimes is tolerated, but don’t add a cockerel (young rooster) older than 6 weeks of age.

A rooster introduced to a flock of all hens typically has few problems. Sometimes a hen or two will challenge him, but he will quickly become lord and master.

Adding some new hens to old hens is the most frequent type of introduction in small flocks. Don’t just toss the new birds in and hope for the best, though. If you’ve ever watched females of any species fight, you know how vicious they can get. Try to introduce more than one bird at a time, to divide up the bullying a bit.

If you can move all the birds to new quarters, old and new, less fighting will ensue. Another way to introduce new birds is to put them in a cage or enclosure next to the old flock members for a few days. The old birds can let them know who’s boss without actually harming them.

Usually, young hens allow older birds to dominate them if the older ones are active and healthy. But sometimes the tables get turned and an older bird gets the worst of it. Different breeds are sometimes more assertive or aggressive. Silkies, Polish, and other breeds with topknots or crests, along with Cochins and some of the smaller bantam breeds, may be bullied by younger birds of large active breeds.

If you can’t pen newcomers nearby for a few days, put them in the pen at night, after the regular flock has gone to bed. Then keep a close eye on the flock in the morning. Or release new birds into the shelter area of a coop after the old birds are let out to do a little free roaming.

Expect some fighting, and don’t interfere unless a bird is injured and bleeding. The flock is establishing a new order, and when they all know their places, the fighting will cease. Remove any bleeding birds because they may be quickly pecked to death. Often a rooster will interfere in the fighting. Roosters are attracted to the new girl or girls and sometimes protect them. Also, roosters don’t like too much strife in their households and may punish the offending birds.

Keep an eye on newcomers for a week or so and make sure they’re getting to the food and water. If they stay huddled in a corner, you may have to remove them. Never spray the birds with water or concoctions of scented products to try to confuse them about who is new. It doesn’t work, and it just brings more stress to the flock.

Discouraging bullying behaviors

By nature, chickens pick on weak members of the flock. If they draw blood, chickens keep picking at the wound, often until they kill the injured bird. A dead bird may be pecked at and eaten if you leave it in the pen. This act doesn’t mean chickens are vicious; it’s just how nature designed them — to be opportunistic feeders. Immediately separate any dead, injured, or ill chicken from the others. Maintaining crowded conditions and frequently moving birds in and out of the flock causes more fighting, which increases the chance for wounds.

Chickens are conscious of colors and patterns, and they often pick on a bird that has different coloring, color patterns, or feathering than the majority breed, especially in brooder housing. Chickens with topknots are frequently picked on by other types of chickens. Watch these birds carefully and remove them if they’re bullied.

Cannibalism and feather picking are signs of poor management. In a home flock, you likely won’t have many problems with these issues, as long as you feed the chickens a proper diet and maintain housing that isn’t crowded. In nature, chickens spread out and spend most of the day searching for food and keeping busy. Plus, they have enough space to avoid higher-ranked flock members. Home flocks that get at least some free-range time each day rarely experience problems.

Confined chickens need to have food available at all times and may benefit from some busywork, such as pecking at a head of cabbage, a squash, or a pumpkin, or looking for scratch grain scattered in the bedding. Raw vegetables, fruit, and whole grains provide roughage. Research has shown that chickens on diets without animal protein and/or low roughage are more prone to feather picking, which often leads to wounds and cannibalism. Properly balanced commercial diets supplement vegetable protein with the needed amino acids found in meat-based diets.

Very bright lights in brooders, stress caused by predators, too much handling, excessive noise, and other conditions sometimes cause feather picking. Changing brooder bulbs to infrared bulbs or bulbs with lower wattages may help. Changing conditions to reduce stress is always desirable. Sometimes only one or two chickens seem overly aggressive, and you may need to sell or destroy them.

Employing Optional Grooming Procedures

Marking your birds so that you can identify them has some benefits. If you’re going to show birds, identify them in a permanent manner. In a flock of similarly colored birds, you may want to identify birds for medication, for planned mating, or for other reasons.

In addition to marking chickens for identification, other practices are designed either for the welfare of the chicken or for showing purposes.

Dubbing, for example, is the old practice of removing a chicken’s healthy comb, usually in a rooster. The wattles, the fleshy lobes under the beak, are also removed. Dubbing was traditionally done with fighting breeds to keep them from being torn during a fight, and it remains a practice for showing Old English and Modern Game breeds in the U.S. Other countries have banned this practice. Cockfighting is illegal. If you’re not showing birds, you have no need for this painful practice.

Marking birds for easy identification

You can purchase leg and wing bands from most poultry supply catalogs and at many poultry shows. Some poultry clubs and organizations also sell bands for their members. The bands may be made of metal or plastic, and they may be flat or round in shape. They come in different sizes to accommodate different breeds of chickens.

Bands are either temporary or permanent:

- Permanent bands are numbered bands that are slipped on the legs of chicks and remain on them for life. Metal or plastic numbered bands can also be clamped through the wing web for permanent marking. Some supply houses let you choose a combination of letters and/or numbers for bands, especially if you order a lot of them, but most supply houses sell prenumbered bands. Permanent bands are usually required at shows, except for meat birds.

- Temporary bands may be either numbered or colored. A temporary band usually consists of a coil that’s spread apart and clasped on the leg for temporary identification purposes. Plastic write-on bands, similar to hospital bands, are also available. They can be slipped over the top of the chicken’s wings at the shoulder. Temporary bands are useful for keeping track of certain birds for mating, for compiling egg production records, and for medicating.

Valuable chickens can also be microchipped like other pets. To microchip your birds, you must purchase the chips, something to insert the chips (usually a large syringe and needles), and a service to serve as a repository for the information contained on the microchip. A chip is about the size of a grain of rice. Microchips need to be read with a machine, and the biggest drawback with their use in chickens is that few people think to use a scanning machine to find an owner or prove ownership.

Trimming long, curled nails

Chickens kept in cages or on soft flooring all the time may develop long, curled nails that can get caught in flooring or make walking difficult. Be sure to trim these long nails. Any pet nail-trimming device can do the job. You’ll also need someone to hold the bird while you trim the nails.

Don’t trim too much off at one time because a vein that runs about ¾ of the way up the nail will bleed profusely if you cut it. It grows as the nail grows, so taking off only about ¼ of the nail at one time is all that’s safe. If you look at the nail in good light, you can probably see the small red vein running through it. Cut just before this vein.

If you nick the vein, put pressure on the cut end with a cloth or paper towel to stop the bleeding. Styptic powders, sold in pet and livestock catalogs and stores, are designed to stop bleeding. Just wipe off the blood and quickly apply the powder. In a pinch, a bit of flour may stop the bleeding, or you can press the bleeding nail into a potato.

Make sure the bleeding has stopped before you return the bird to its pen. Other birds will peck at the bloody area.

Trimming wings and other feathers

Wing trimming is sometimes done to keep chickens from flying over the pen walls, although some lightweight birds may get enough lift to escape even with their wings trimmed. Trim only the large flight feathers, and understand that you’ll need to do it again when the feathers grow back after the next molt. Sometimes trimming the feathers on just one wing is enough. Keep in mind that chickens can’t be shown if they have trimmed wings.

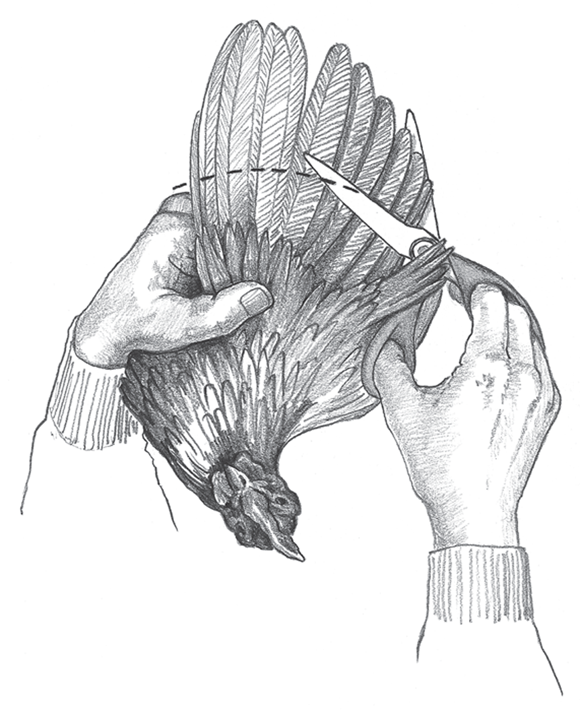

To trim the wing feathers, have someone restrain the chicken for you. Pull the wing out away from the body and, using sharp, strong scissors, cut across the middle of all the long flight feathers (see Figure 10-1). If you hit an immature feather and it begins to bleed, grasp the feather close to where it joins the wing and pull it out. Removing the feather should stop the bleeding.

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 10-1: How to clip the wing feathers of a chicken.

Pulling out feathers is somewhat painful for the chicken, so cutting them is better than pulling them out. Another advantage to cutting versus pulling is that feathers that are pulled out often regrow before the molt, whereas cut feathers don’t regrow until they’re shed during molt.

With breeds that have topknots, it’s often helpful to trim the topknot feathers over the eyes so the chickens can see. When they can see better, they’re more active, and other breeds are less likely to pick on them. However, don’t trim the topknot feathers with show birds, or they’ll be disqualified.

In some heavily feathered breeds, feathers around the rear end may become matted. Even if they’re not matted, they can interfere with mating. You can carefully trim these feathers.

It’s a good idea to have a dedicated quarantine space available regardless of whether you plan on showing your birds. Illness, new birds added to the flock, and various other reasons require a quarantine space. If you have one at the ready before an issue arises, you’ll be that much more prepared.

It’s a good idea to have a dedicated quarantine space available regardless of whether you plan on showing your birds. Illness, new birds added to the flock, and various other reasons require a quarantine space. If you have one at the ready before an issue arises, you’ll be that much more prepared. Diseases can also spread to home flocks from wild birds and from pests like raccoons, opossums, insects, and rats. See

Diseases can also spread to home flocks from wild birds and from pests like raccoons, opossums, insects, and rats. See