Chapter 3

A Chicken Isn’t Just a Chicken: Your Guide to Breeds

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Understanding breed basics

Understanding breed basics

![]() Checking out breeds for eggs and meat

Checking out breeds for eggs and meat

![]() Looking at show, pet, and rare breeds

Looking at show, pet, and rare breeds

A chicken breed is a group of chickens that look similar, have similar genetics, and, when bred together, produce more chickens similar to them. Breeds don’t just emphasize visual differences, however. Just like most domesticated animals, chickens have been selected over time for their ability to fit certain needs that humans have for them. Some chickens are better as meat birds, some are better at laying eggs, and some are just better looking.

Chickens have been selected and bred for certain traits for many reasons, including desires to produce birds that:

- Lay more eggs

- Lay different-colored eggs

- Grow faster

- Provide more breast meat

- Behave more calmly

- Are resistant to disease

In this chapter, we introduce you to breed terminology and discuss how chicken-keepers categorize breeds. Then we explain the most common breeds within each category and give you a mini-biography about each one — we’ve kept them short and sweet, promise!

What You Need to Know: A Brief Synopsis

In the next few sections, we define some terms you’re likely to come across when researching chicken breeds. After that, we talk about some breeds of chickens that we consider good breeds — although what constitutes a good breed for you is subjective, and some of the breeds we don’t mention here are still “good” breeds.

The breeds are organized into groups. The heading for each group directs your attention to the common use of the breeds in that group. Thus, if you want to keep chickens for eggs, you can go right to the breeds under “For Egg Lovers: Laying Breeds,” and so on.

Common breed terminology

As you explore the world of chicken breeds, you’re likely to come across a handful of commonly used terms: purebreds, hybrids, strains, mutations, and mixed breeds. In the following sections, we tell you what they mean and what you need to know to get up to speed in no time.

Purebreds

Purebred chickens are chickens that have been bred to similar chickens for a number of generations and that share a genetic similarity. If you breed two chickens from the same breed, you should get offspring that look much like the parents. If you own a backyard flock and want to produce new chicks every year from your flock, or if you’re interested in showing chickens, you’ll want to purchase purebred chickens.

While more than 200 breeds of chickens are known to exist, with many color varieties within those breeds, fewer than half of these breeds are common. In fact, the vast majority of chickens in existence today belong to one of just a few breeds — White (or Pearl) Leghorns, Rhode Island Reds, Cornish, and Plymouth Rocks — and crosses of those breeds. These breeds comprise the commercial chicken industry for eggs and meat. The other breeds can thank small-scale chicken-keepers like you for their continued existence: Those independent chicken-keepers see value in maintaining genetic diversity and keep them from disappearing.

Hybrids

Many common and well-known chicken “breeds” are not breeds at all, but hybrids. Hybrids result from crossing two purebreds (see the preceding section). Animal breeders have long known that crossing two purebred animals of different breeds often produces a hybrid animal with good traits from both parents, along with increased health and productivity.

Hybrids are for end use — that is, they’re good for only one purpose. Hybrid chickens may produce the most tender meat in the shortest time or lots of big eggs. These birds can’t be bred to each other to produce a new flock: When hybrids are bred together, the results are unpredictable. Some babies look like one parent, and some look like neither. Thus, to maintain a supply of hybrid birds, you must raise two separate purebreds as parent stock.

Strains

Both purebreds and hybrids can be further defined as particular strains. A strain is usually one breeder’s selection and is based on how that breeder feels the stock should look. Purebred strains represent the basic breed characteristics but may be slightly bigger, more colorful, hardier, and so on. In the case of hybrids, the birds that result from mating two particular purebred birds may also be called strains if they’re produced by only a single company or breeder.

Strains are often named, especially if they’re produced in large numbers for commercial use. The Cornish and White Rock hybrid has several strains. Some have names, like Cornish X or Vantress, whereas others are identified by numbers. Some strains grow faster, some survive heat better, some have white skin, and so forth. The same genetics firm may offer several strains.

Mutations

Occasionally, a mutation pops up, causing a chicken to look or act differently than the birds it was bred from. This scenario is nature accidentally rearranging genetic material. Mutations can be good, bad, or unimportant. Sometimes, with careful breeding, good mutations can turn into breeds.

Mixed breeds

Just as the world of dogs has many mutts, the world of chickens has mutt chickens. Mixed-breed chickens are birds whose ancestry isn’t known, and they’re a combination of many breeds. Mixed-breed chickens can be a great way to start a home flock. In fact, mixed-breed chickens often result from a chicken owner starting with a variety of purebred chickens and letting them breed. If you just want some average layers or chickens for that country feel, go with mixed breeds. The only problem is that if you don’t know the parents of a bird that turns out to be beautiful or very productive, you’ll have a hard time breeding more birds like it.

Over time, flocks of mixed-breed birds that are allowed to reproduce indiscriminately tend to produce smaller, less productive, and perhaps less healthy birds. The chickens tend to revert back to the size, color, behavior, and laying habits of their wild ancestors.

How breeds are categorized

From the earliest times, humans and animals have been categorized in some way — hunters, gatherers, herders, and so on — and chickens are no different. To make choosing the breeds you want to raise easier, chickens are grouped into the following categories:

- Dual-purpose breeds: Dual-purpose breeds are the kind many people keep around the homestead. They lay reasonably well, are calm and friendly, and have enough meat on their bones that excess birds can be used for eating.

- Egg layers: The laying breeds won’t sit on their own eggs. In the first year of production, they may lay 290 to 300 eggs and only slightly less for the next 2 years. They don’t make good meat birds, although they can be eaten.

- Meat breeds: Meat birds were developed to have deeper, larger breasts; a larger frame; and fast growth. Most of the chickens we call meat breeds are actually hybrids, although some purebreds, such as the Cornish, are considered great meat birds. Meat-type birds generally don’t lay well.

- Show breeds: Some chickens are kept for purely ornamental reasons. They generally don’t lay a lot of eggs, although their eggs are certainly edible. Most ornamental-type birds don’t make good meals, either, although any chicken can be eaten. These birds are kept for their beautiful colors or unusual feathers.

- Bantam breeds: Bantams are miniature versions of bigger chicken breeds or small chickens that never had a larger version. If there’s no large version, they’re called true bantams. These birds range from 2 to about 5 pounds.

Within almost all breeds, you’ll find several color variations. Colors are hard to describe in print. If you’re unsure about what a color should look like, refer to a good catalog or reference book, such as the American Standard of Perfection mentioned at the beginning of the chapter.

For many breeds, some color variance between male and female chickens is normal. Even if the chickens are a solid color, however, males generally have different tail feather structure, larger combs and wattles, and some iridescence to their feathers. Chapter 2 explains sexual differences.

If You Want It All: Dual-Purpose Breeds

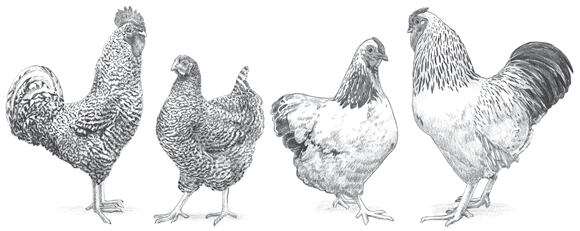

Home flock owners often want chickens that will give them a decent amount of eggs and also be meaty enough so that they can use excess birds as meat birds. The eggs taste the same; you just don’t get as many as you do from laying breeds. The meat tastes the same if you raise the dual-purpose birds like you raise meat birds, but their breasts are smaller and the birds grow much more slowly. Some of the birds classified as dual-purpose breeds in the following list were once considered to be meat breeds until the Cornish X Rock cross came along (see the section “Best Breeds for the Table”). Figure 3-1 illustrates common dual-purpose breeds, including these breeds:

- Barnevelders: The Barnevelder is an old breed that’s making a comeback because of its dark brown eggs. Barnevelders are fair layers and are heavy enough to make a good meat bird, although they’re slow growing. They come in black, white, and blue-laced, as well as other colors. These calm, docile birds are fluffy looking and soft feathered.

- Brahmas: The Brahma is a large, fluffy-looking bird that lays brown eggs. Brahmas are good sitters and mothers and, as such, are often used to hatch other breeds’ eggs. They’re good meat birds, but they mature slowly. Their feet are feathered, and they come in several colors and color combos. They withstand cold weather well, and they’re calm and easy to handle.

- Orpingtons: Orpingtons deserve their popularity as a farm breed. They’re large, meaty birds, and they’re pretty good layers of brown eggs. They’ll also sit on eggs and they’re good mothers. Buff or golden-colored Orpingtons are the most popular, but they also come in blue, black, and white. These birds are calm and gentle. They can forage pretty well but don’t mind confinement.

- Plymouth Rocks: These birds are an excellent old American breed, good for both eggs and meat. White Plymouth Rocks are used for hybrid meat crosses, but several other color varieties of the breed, including buff, blue, and the popular striped black-and-white birds called Barred Rocks, make good dual-purpose birds. They’re pretty good layers of medium-size brown eggs, they’ll sit on eggs, and they’re excellent home meat birds. They’re usually calm, gentle birds, good for free-range or pastured production.

- Wyandotte: These large, fluffy-looking birds are excellent as farm flocks. They’re pretty good layers of brown eggs (some will sit on eggs), and they make excellent meat birds. They come in several colors, with Silver Laced and Columbian being the most popular. Wyandottes are fairly quick to mature, compared to other dual-purpose breeds. Most are docile, friendly birds.

- Turken/Transylvanian Naked Neck: With an odd name like this, you may think this breed was crossed with a turkey — but it isn’t. This breed comes in many colors, but the distinguishing feature is a lack of feathers on the neck. The genes that make the neck bare also contribute to a good-sized, meaty breast area in the chicken and make it easier to pluck. These birds are fairly good layers of medium to large light brown eggs. While they may look ugly, Turkens are calm and friendly birds.

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 3-1: Common dual-purpose breeds — Barred Plymouth Rock (left) and Wyandotte (right).

For Egg Lovers: Laying Breeds

If you want hens that lay a certain color of eggs, you can read breed descriptions or you can look at the color of the skin patch around the ear. Hens that have white skin around the ear generally lay white eggs. Hens that have red skin around the ears generally lay brown eggs, in any number of shades. (There’s no way to tell what shade of brown from looking at the ear patch.) The breeds that lay greenish-blue eggs usually have red ear-skin patches.

White-egg layers

The white-egg layers in the following list (see Figure 3-2 for an illustration) are the most productive, although many others also exist. Although there are individual exceptions, white-egg layers tend to be more nervous and harder to tame than brown-egg layers. That may be why many home flocks consist of the latter. But if you want a lot of white eggs, the following birds are the best breeds to choose from:

- White or Pearl Leghorn: This bird accounts for at least 90 percent of the world’s white-egg production. It’s lightweight and has a large, red, single comb. Leghorns also come in other colors that don’t lay as many eggs but are fine for home flocks. Leghorns tend to be nervous and don’t do as well in free-range or pastured situations as other breeds. California Whites are a hybrid of Leghorns and a Barred breed that are quieter than Pearl Leghorns. Other hybrids are also available.

- Ancona: Anconas lay large white eggs. They’re black feathered, and some feathers have a white tip that gives the bird a “dotted” appearance. They’re similar in shape to the Leghorn. Anconas are flighty and wild acting. Originally from Italy, they’re becoming rare and harder to find.

- Andulusian: The Andulusian chicken was once much rarer, but this breed has enjoyed an upswing in popularity in recent years. Originally developed in Spain, the bird is known for its beautiful blue-gray shade; the edges of the feathers are outlined in a darker gray. These chickens are good layers of medium to large white eggs. They are lightweight birds and like to fly, which can be a problem when confining them. Andulusians are a purebred breed of chicken, but the blue color doesn’t breed true: Offspring can be black or white with gray spots, called a splash. These colors are equally fine as layers — they just can’t be shown.

- Hamburg: One of the oldest egg-laying breeds, Hamburgs are prolific layers of white eggs. They come in spangled and penciled gold or silver, or solid white or black. Hamburgs of all colors have slate-blue leg shanks and rose combs. They’re active birds and good foragers, but they’re not especially tame.

- Minorca: Minorcas are large birds that lay lots of large to extra-large white eggs. They come in black, white, or buff (golden) colors. Minorcas can have single or rose combs. They’re active and good foragers, but they’re not easy to tame. The Minorca is another bird that’s becoming hard to find.

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 3-2: Common breeds that lay white eggs — Minorca (far left), white Leghorn (middle), and Hamburg (right).

Brown-egg layers

For home flocks, brown-egg layers are popular (see Figure 3-3). The brown eggs these birds lay can vary from light tan to deep chocolate brown, sometimes even within the same breed. As hens get older, their eggs tend to be lighter in color. Some of the best brown-egg layers follow:

- Isa Brown: This hybrid makes up the world’s largest population of brown-egg layers. Isa Browns are a genetically patented hybrid chicken. Only a few hatcheries can legally produce and sell the chicks, which means chicks hatched at someone’s home or at a hatchery other than a licensed one aren’t selling real Isa Browns. Isas are a combination of Rhode Island Red and Rhode Island White chickens — which are considered to be separate breeds, not colors — and possibly other breeds. Isa Brown hens are red-brown in color, with some white under-feathering and occasional white tail feathers; the roosters are white. The hens lay large to extra-large brown eggs that range in color from light to chocolate brown. These calm and gentle birds are easy to work with and are also good foragers. They may be production birds, but they have great personalities and are people-friendly. The disadvantages are that they can’t be kept for breeding (they don’t breed true), and the roosters don’t make good meat birds.

- Amber Link: This breed is a close relative to the Isa Brown, with a slightly darker brown egg that tends to be medium to large in size. Amber Links are white with some gold-brown feathers in the tail and wing area. They’re productive and hardy, and they’re are also calm, gentle birds. You’ll probably be able to find them only at hatcheries that sell Isa Browns.

- Red Star, Black Star, Cherry Egger, and Golden Comet: All these are variations of the same breeding that produced Isa Browns. Some were developed from New Hampshires or other heavy breeds other than Rhode Island Reds. They’re prolific layers of brown eggs, but they won’t sit on eggs. They also don’t make good meat birds because of their light frames. They’re usually calm and friendly birds. If you’re not going to breed birds and you just want good egg production, any of these chickens will fill the need.

- Australorp: A true breed rather than a hybrid, Australorps lay a lot of medium-size, light-brown eggs. Before Isa Browns, they were the brown-egg-laying champions. Both the hens and the roosters are solid black birds with single combs. They’re calm, they mature early, and some will sit on eggs. They were developed in Australia from meat birds, and the roosters make moderately good eating.

- New Hampshire Red: New Hampshire Reds are similar to Rhode Island Reds, and the two are often confused with one another. True New Hampshire Reds are lighter red, they have black tail feathers and the neck feathers are lightly marked with black. They’re more likely to brood eggs than Rhode Island Reds. New Hampshire Reds are usually calm and friendly but active. The breed has two strains: Some are good brown-egg layers, whereas others don’t lay as well but are better meat birds.

- Rhode Island Red: Rhode Island Reds were developed in the United States from primarily meat birds, with an eye toward making them productive egg layers as well. They lay a lot of large brown eggs. Both sexes are a deep red-brown color and can have a single or rose comb. They’re hardy, active birds that generally aren’t too wild, but the roosters tend to be aggressive.

- Rhode Island White: Rhode Island Whites were developed from a slightly different background than Rhode Island Reds, which is why they’re considered separate breeds and can be hybridized. They lay brown eggs. They birds are white with single or rose combs, and they’re calm and hardy.

- Maran: These birds aren’t recognized as a pure breed in all poultry associations. Sometimes referred to as Cuckoo Marans, cuckoo refers to a color type (irregular bands of darker color on a lighter background). The breed actually has several color variations, including silver, golden, black, white, wheat, and copper. Marans were once rare, but they’re now popular for their very dark brown eggs (remember, though, eggs of different colors don’t taste any different!). Not every Maran lays equally dark eggs. The eggs vary in size from medium to large. Most Marans are good layers, but they’re not as good as some of the previously noted breeds. The various strains exhibit a lot of variation in the breed in terms of temperament and whether they will brood.

- Welsummer: Welsummers are also popular for their very dark brown eggs that are medium to large in size. The hens are partridge colored (dark feathers with a gold edge), whereas the roosters are black with a red neck and red wing feathers. As members of an old, established breed, Welsummers are friendly, calm birds. They’re good at foraging, and some will sit on eggs.

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 3-3: Common brown-egg layer breeds — Australorp (left) and Rhode Island Red (right).

Colored-egg layers

Like the brown-egg layers, the colored-egg layers are also popular with home flock owners (Figure 3-4 illustrates two). Colored-egg layers are a novelty. Despite catalogs that show eggs in a rainbow of colors, their eggs are actually shades of blue and blue-green. Sometimes brown-egg layers whose eggs are a creamy light brown are said to lay yellow eggs. Pink, red, and purple eggs are said to exist, but these colors are generally caused by odd pigment mistakes and often aren’t repeated. Some colors also are in the eye of the beholder (or the camera exposure), and what you call pink we may call light reddish-brown.

- Ameraucana: The origin of the Ameraucana is debatable: Some say it developed from the Araucana (see the next bullet), whereas others say it developed from other South American breeds that lay blue eggs. Ameraucanas come in many colors. They have puffs of feathers or muffs at the side of the head, and some have beards. They have tails, which help distinguish them from Araucanas. Their temperament varies; however, many will sit on eggs. The eggs are blue or blue-green.

- Araucana: This breed of chicken is seldom seen in its purebred form. Many chickens sold as Araucana are actually mixes, so buyer beware. Purebred Araucanas have no tail feathers. Either they have tuffs, small puffs of feathers at the ears, instead of large “muff” clumps or they’re clean faced. They don’t have beards, and they have pea combs. Most have willow (gray-green) legs. The breed has many color variations. Araucanas lay small blue to blue-green eggs and are not terribly prolific layers. They’re calm and make good brooders.

- Easter Egger: These birds are mutts in the world of chickens because no one is quite sure of their background. They’re usually a combination of the previous breeds and maybe some other South American blue-egg layers or other layers. They can be a bit more prolific in egg laying, but the egg color and temperament of the birds, as well as their adult body color, range greatly. They lay shades of blue, blue-green, and olive eggs.

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 3-4: Common colored-egg layer breed — Araucana.

Best Breeds for the Table

In the not-so-distant past, most meat chickens were young males that were the excess offspring from laying or show birds. They were kept just long enough to make a good meal — and that usually meant about 5 to 6 months of feeding and caring for the young roosters. The excess males in most heavy, generally brown-egg-laying breeds of chickens were used as meat. And in your great-grandparents’ day, any hen that quit laying was also used for meat.

About 50 years ago, breeders began to create hybridized strains of chickens specifically for meat (see Figure 3-5). They grew fast and gained weight quickly on less feed than other chickens. They had more breast meat, something consumers seem to want. Over the years, these hybrids — particularly one hybrid, a cross between White Rocks and White Cornish breed chickens — have dominated the commercial meat market. In fact, almost every chicken you can buy in a grocery store is a strain of the previously mentioned cross.

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 3-5: Common meat breeds — Jersey Giant (left) and Cornish X Rock (right).

Most meat birds stem from one hybrid, but home flock owners can consider other good meat breeds as well. Many backyard breeders are trying to develop meat breeds that grow quickly and have good meat yield, but are hardy and active enough to do well in pasture or free-range situations.

The meat of these other meat breeds may taste slightly different if the birds are raised on pasture and take longer to grow. The meat is a little firmer, and there’s less breast meat. The taste is described by some as “old-fashioned” chicken flavor, which is hard to describe unless you’ve eaten both types. If the chickens eat commercial feed and aren’t allowed to get too old before butchering, the older type meat birds taste much like hybrid meat birds. The advantage of hybrids is that they grow about twice as quickly and on less feed than conventional meat breeds.

Cornish X Rock hybrids: Almost all chickens sold for meat today are a hybrid of White Cornish and White Rock chickens. They’ve been tinkered with until we now have an extremely fast-growing bird with huge breasts. They’re often ready to butcher at 10 weeks, and they do a remarkable job of converting feed into meat. They have soft, tender-textured, bland-flavored meat and lots of white breast meat. Both sexes make good eating and grow at nearly the same rate. If you have eaten only store-purchased chicken, you certainly know how they taste.

Different strains exist, even some where feather color has been introduced. Basically, however, commercial meat birds are Cornish-Rock crosses. These birds have special nutritional needs and aren’t good for free-range or pastured poultry. They’re excellent if you want quick, plump meat birds, but they’re not good for anything else.

These breeds gave up some features to achieve these “meat goals.” They’re extremely closely related genetically, with three or so large firms controlling the production of parent stock. They have to be managed carefully and fed a high-protein diet to avoid problems with their legs and hearts. Basically, they’re basketballs with feathers, they’re inactive, and they spend most of their time eating. They can’t reproduce normally.

- Cornish: The Cornish is an old breed known for its wide stance and big breasts. Several colors other than the white ones used to make meat hybrids exist, including red, buff, and laced patterns. They have a rose comb, and their feathers are tight and sleek. These birds are poor layers of small white eggs; some will brood. They can be aggressive with each other, but they’re fairly tame with keepers. Cornish chickens are only fair foragers and are better raised in pens.

- Jersey Giants: This American breed comprises the world’s largest chickens. They come in black or white. They’re meaty birds, but they grow slowly. Jersey Giants are fairly good layers of medium-size brown eggs. They’re calm, they’re good at foraging, and they make good brooders.

- Freedom Rangers/Red Rangers: These birds were developed to be good pasture-fed meat birds, primarily for the organic meat market. They thrive on lower-protein feed and are better foragers than Cornish-Rock crosses. Most are red in color, with a few barred or black spotted feathers; gray and “bronze” colors are also seen. These birds take a few weeks longer than the Cornish-cross broilers to be ready to butcher, but many people think they taste better. They’re also less likely to suffer from leg problems or die of heart failure than the Cornish-cross broilers. Rangers can be hard to find, and the breed still has a lot of variability: Some birds mature faster and have more meat than others.

Show Breeds

Some breeds of chickens exist today mainly for pleasure (see Figure 3-6 for a peek at some). They may have been used as layers or meat birds in the past, but better breeds came along and replaced them. The practice of showing chickens keeps many of these breeds alive. Some of the most beautiful chickens may not be good layers or meat birds, so we justify keeping them around by raising them to show. They make excellent lawn ornaments and pets, too:

- Cochin: Cochins originated in China. They’re big, fluffy balls of feathers, with feathers covering the feet, and they come in buff, black, white, and partridge colors. These popular show birds are excellent brooding hens and love to raise families. In fact, they’re often used to hatch other breeds’ eggs. Their own eggs are small and creamy tan. Cochins are calm and friendly, but they may be picked on in a flock with active breeds.

- Polish: Polish chickens are small, silly-looking birds with a floppy crest of feathers that covers their eyes. Their crests may block their vision and make them seem a little shy or stupid, or cause them to be bullied by other chickens. If you’re not showing them, trim their crests so they can see better. Some Polish also have beards. These birds come in several colors: One of the most popular is a black-bodied bird with a white crest. Polish lay small, white eggs that they generally won’t sit on.

- Old English Game/Modern Game: Both of these breeds were once bred for fighting but are now used for show. People either like or hate the look of these birds. They stand very upright, with long necks and legs and tight, sleek feathers. They come in numerous colors. They’re active and aggressive birds. Modern Games are larger and heavier. Both types lay small white eggs. Old English Games are good brooders and mothers; Modern Games are less so.

- Appenzeller Spitzhauben: This small, sprightly breed has topknot that often looks like a Mohawk and sports a black-and-white polka dot feather pattern. It has become a great show bird for youth, even though the Switzerland-based breed isn’t officially recognized in many U.S. poultry shows. The birds are fairly good layers of white eggs.

- Cubalaya: This breed came to us from Cuba in the last century and has both full-sized and bantam chickens. The Cubalaya’s distinguishing feature is its long, flowing tail that it carries very low. In show chicken terms, this type of tail is called a lobster tail. The birds come in a variety of colors. They also lack a spur, the sharp, hooklike structure on the back of a chicken’s leg used for fighting. It’s difficult to find a bird with a good tail — and also hard to then keep that tail in good condition. The birds are fair layers of cream-colored eggs and are calm and friendly, although they do like to fly and they range widely.

- Houdans: The Houdan is an oddity because it has five toes, compared to most chicken breeds that have four. It’s an old breed from France and comes in two colors, white and also black splashed with white, called a mottled Houdan. They also have big, fluffy topknots, similar to the Polish. This type matures quickly and was once used for meat, although it is a smaller bird. It’s a pretty good layer of white eggs. Houdans, like other crested, topknot breeds are often picked on by other types of chickens and seem a little stupid. Trimming the feathers so they can see does wonders. These birds are generally calm and friendly.

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 3-6: Common show and pet breeds — Old English Game (top left), Cochin (top right), and Polish (bottom).

Perfect for Pets: Bantam Breeds

In chickens, selective breeding using the smallest birds of each generation has produced small breeds called bantams. A few breeds have some dwarf genes. People have always enjoyed seeing miniature versions of domestic animals. Bantam chickens are primarily kept for show or as pets, as are most other small versions of domestic animals.

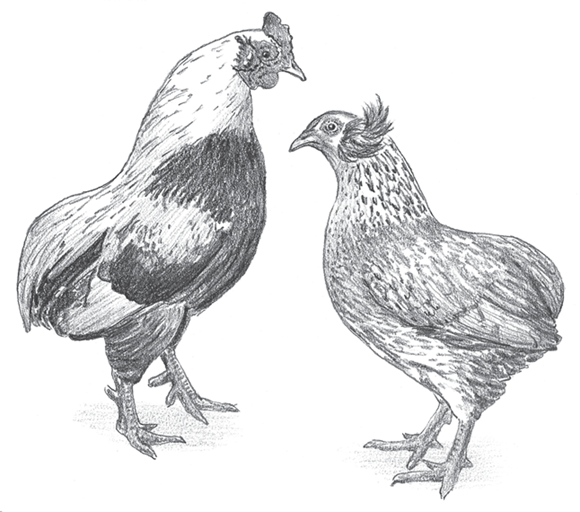

Almost every standard chicken breed has bantam varieties, and some bantam breeds exist only in the small size. When the bantam has a full-size counterpart, the breed description is basically the same, except that the bantams are much smaller. When a chicken has no full-size representative, it is called a true bantam (see Figure 3-7).

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 3-7: True bantams — the Silkie (top) and the Japanese bantam (bottom).

Bantams are seldom heavy layers, but the small eggs are still good to eat and taste exactly like other chicken eggs. The eggs are the same color as eggs laid by a full-size example of the breed. However, bantams do not make good meat birds. Because most bantam breeds look just like the full-size version of the breed, we describe only true bantams here — breeds that don’t have full-size counterparts:

- Silkie: The Silkie is probably one of the most popular pet chickens. Silkies may be quite small or a bit larger, but all have distinctive furlike feathers. They’re so cute that you may want to cuddle them, and some don’t mind being handled. Some have beards, and they come in black, blue, white, buff, and other colors. The skin of Silkies is black, and their combs and earlobes are dark maroon-red, with a turquoise area around the ear. Silkies are the ultimate mothers. They love to sit on eggs and happily raise anyone’s babies. They’re sometimes picked on by more active breeds. Silkies lay white eggs.

- Japanese: The Japanese bantam has tiny, short legs and a high, arched tail, often in a color that contrasts with the body. It comes in many colors and color combinations and weighs about a pound. Most Japanese bantams are friendly, although the roosters sometimes get mean. Japanese bantams lay white eggs.

- Serama: The Serama bantam is the smallest chicken breed in the world (about 1 pound or less) and one of the newest, developed in only the last 50 years. Chickens from this breed can be hard to find and expensive. The tiny birds have an odd V shape to them, with a full breast held very upright and a tail carried straight up. The wings point down and touch the ground. Seramas come in a variety of colors, and there is a Silkie feathered variation, too. The tiny chicks need to be raised with special care, and the birds are not cold hardy; they require heated housing in the winter.

- Sebright: The Sebright bantams come in gold and silver as base colors. Each feather is outlined in black, making a pretty pattern. They can be hard to sex because the roosters and hens look so similar. Sebrights have a rose comb (short and crumbled looking) that comes to a spike point in the back. They’re active birds and can be aggressive with each other.

- Antwerp Belgian Bantam: These birds are very small. They have a rose comb like the Sebright, a muff of feathers around the ear lobe, and a fluffy beard under their beak. They come in several colors and are active and friendly little birds.

- Mille Fleur: The color of Mille Fleurs is hard to describe. The base feather color is reddish-gold over the body and wings, with black on the feet and tail. But each feather has a white dot on the end and then a black area, giving the bird a spangled appearance. The feet of Mille Fleurs are covered in feathers, or “booted.” The breed has two subvarieties: bearded and nonbearded. Bearded birds have muffs of feathers under the earlobes and a beard that runs under the beak. These beautiful little birds make excellent pets.

- Porcelain: These tiny bantams are much like the Mille Fleur, with bearded and nonbearded categories. The color of the Porcelain is pale yellow with a blue area just before the white “spangle” on the feather tip. The tail and feet feathers are blue-gray tipped in white. These birds are quiet and gentle.

Heritage and Rare Breeds

Determining which breeds are rare is difficult because many poultry breeds are getting scarce. The genetics of many breeds need to be preserved because the genetic pool of chickens is becoming limited. Poultry breeds go through fads: For example, the current craze is for chickens that lay very dark brown eggs. Welsummers, Marans, and Penedesencas were once very, very rare in the United States, but they’re rapidly gaining in numbers due to the dark brown egg craze.

- Buckeye: The Buckeye is an American breed, developed by a woman in Ohio in the late 1800s. Buckeyes are a deep brown color, with some black in the tail. Although they bear some similarities to Rhode Island Reds, Buckeyes make better meat birds because of their deeper, broad-breasted bodies. Good foragers and winter hardy, they’re also good layers of brown eggs — perfect homestead chickens that deserve more attention.

- Chantecler: The Chantecler was developed in Canada as a homestead chicken for meat and eggs. It comes in white and partridge colors. Chanteclers lay brown eggs, are good foragers, and mature quickly. They will brood eggs. They’re not particularly people-friendly birds.

- Delaware: Delawares are layers of medium to dark brown, medium-size eggs. They were developed in the United States and are starting to make a comeback after almost fading away as a breed. They’re white, with some black ticking in the feathers of the neck and tail. They’re calm, they sometimes brood their eggs, and they make decent meat birds, too. They’re good layers for cold areas.

- La Fleche: The La Fleche is known as the Devil Bird because its comb is shaped like a horn. La Fleches are good layers of large, creamy white eggs. They come in black, blue, white, and cuckoo colors. Fairly good as meat birds, they’re quick to mature. They’re now quite rare.

- Faverolle: Faverolles are pretty and also efficient egg layers. Their eggs tend to be medium in size and creamy rather than pearl white. Faverelles come in two colors: white and salmon. (The salmon color is actually black and white with fawn, or salmon, wing and back areas.) The Faverolle has a “muff” of feathers around the ears, a beard, and lightly feathered feet with a fifth toe. Faverolles are calm and tame, good for home flocks, and will sometimes sit on eggs.

- Penedesenca: Still fairly rare in the United States, Penedesencas were developed in Spain and are good layers of small, very dark brown eggs. The birds come in several colors and have an unusual comb shaped like a crown. They’re rather wild, they withstand heat well, and they’re good free-range birds.

- Campine: The Campine is an old breed that originally came from Belgium. It has two color varieties, gold and silver. The gold has golden feathers marked with black bars, and the silver is gray-white with black bars. When the two colors are crossed, they produce chicks that can be sexed by color right after hatching. Female chicks are a red-buff color, and males have a gray cap on their head. Campines were originally developed as a dual-purpose breed and are fairly good layers of white eggs. Both colors are rare now, with silver being the rarest.

- White-Faced Black Spanish: This breed has been a little more popular recently and isn’t quite as hard to find as it once was. The breed originated in Spain, as the name suggests. These birds are tall and graceful, with glossy black feathers, large bright red combs, and large white earlobes, which contribute to their name. As the birds mature, the rest of the facial area also becomes white. They lay white eggs. These birds are active and can be aggressive with other chickens.

- Egyptian Fayoumis: The Egyptian Fayoumis are an old breed originating along the Nile River in the Middle East and brought to the U.S. this century to utilize their traits of quick maturity and resistance to disease. The birds are small, about 2 pounds in weight. Egyptian Fayoumis have slate-blue skin, silver neck feathers, and black-and-white barred body feathers. The birds are pretty good layers of small white eggs. They fly well, tend to be on the wild side, and are quite noisy.

Throughout this chapter, we give you an overview of the most common breeds that the casual chicken-keeper needs to know about. If you’re interested in breeding purebred chickens or showing chickens, you’ll want to dig a little deeper into breed characteristics and color varieties. The American Poultry Association publishes a book called American Standard of Perfection every few years that includes color photos and complete breed descriptions. You may be able to find it at a library or at your county Extension office, or you can purchase it from the American Poultry Association, P.O. Box 306, Burgettstown, PA 15021; phone 724-729-3459;

Throughout this chapter, we give you an overview of the most common breeds that the casual chicken-keeper needs to know about. If you’re interested in breeding purebred chickens or showing chickens, you’ll want to dig a little deeper into breed characteristics and color varieties. The American Poultry Association publishes a book called American Standard of Perfection every few years that includes color photos and complete breed descriptions. You may be able to find it at a library or at your county Extension office, or you can purchase it from the American Poultry Association, P.O. Box 306, Burgettstown, PA 15021; phone 724-729-3459;  It’s important to remember that all colors of eggs have exactly the same nutritional qualities and taste.

It’s important to remember that all colors of eggs have exactly the same nutritional qualities and taste.