Chapter 2

Basic Chicken Biology and Behavior

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Checking out basic chicken anatomy

Checking out basic chicken anatomy

![]() Determining whether a chicken is healthy

Determining whether a chicken is healthy

![]() Getting a glimpse of how chickens behave

Getting a glimpse of how chickens behave

![]() Seeing how chickens interact with other animals

Seeing how chickens interact with other animals

Most people can identify a chicken even if they’ve never owned one. A few chicken breeds may fool some folks, but by and large, people know what a chicken looks like. However, if you’re going to keep chickens, you need to know more than that. To select and raise healthy birds, which involves understanding breed variations, identifying and treating illness, and talking about your chickens (particularly when seeking healthcare advice or discussing breeding), you need to be able to identify a chicken’s various parts. In the first part of this chapter, we cover basic chicken biology.

When raising chickens, you also need to know how to tell whether a chicken is healthy, so we describe what a healthy bird looks like. Last but not least, to adequately care for and interact with birds, you need to know a bit about their daily routines — how they eat, sleep, and socialize — as well as their molting and reproduction cycles and behavior. This chapter is your guide.

Familiarizing Yourself with a Chicken’s Physique

Domestic breeds of chickens are derived from wild chickens that still crow in the jungles of Southeast Asia. The Red Jungle fowl is thought to be the primary ancestor of domestic breeds, but the Gray Jungle fowl has also contributed some genes. Wild chickens are still numerous in many parts of southern Asia, and chickens have escaped captivity and gone feral or “wild” in many subtropical regions in other parts of the world. So we have a pretty good idea of the original appearance of chickens and their habits.

Our many dog breeds are an example of what man can do by selectively breeding for certain traits. Dog breeds from Chihuahuas to Saint Bernards derived from the wolf. During domestication, not only did the size change, but the color, hair type, and body shape were altered in numerous ways as well. Chickens may not have as many body variations as dogs, but they do have a few, and man has managed to change the color and “hairstyles” of some chickens as well.

Wild hens weigh about 3 pounds, and wild roosters weigh 4 to 4½ pounds. More than 200 breeds of chickens exist today, ranging in size from 1-pound bantams to 15-pound giants. Wild chickens are slender birds with an upright carriage. Some of that slender body shape remains, but modern chicken breeds have many body variations. When you bite into a juicy, plump chicken breast from one of the modern meat breeds, you’re experiencing one of those body variations firsthand.

Domestic chickens come in a wide range of colors and patterns of colors. In the next chapter, we discuss some of the chicken breeds that have been developed. Modern chickens generally keep the distinct color differences between male and female, with the males remaining flashy and the females more soberly garbed. However, in some breeds, such as the White Leghorns and many other white and solid-color breeds, both sexes may be the same color.

Even when the chickens are a solid color, differences in the comb and shape of feathers help distinguish roosters from hens. However, in the Sebright and Campine breeds of chickens, the hens look like the roosters, with only a slight difference in the shape of the tail. To see the differences between roosters and hens, refer to Figure 2-1 later in this chapter.

It’s really quite amazing how man has been able to manipulate the genetics of wild breeds of chickens and come up with the sizes, colors, and shapes of chickens that exist today.

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 2-1: Comparing a rooster and hen.

Labeling a Chicken’s Many Parts

When you look at the chickens you are raising or intend to raise, it’s important to know how to properly discuss the various parts of the chicken’s body. Calling a chicken leg “the drumstick” or referencing the “wishbone” probably isn’t the best way to communicate with other chicken owners or with a veterinarian. You need to be able to identify parts you don’t see in the supermarket.

And when you’re looking through the baby chick catalog or advertisements for chickens, you’ll want to know what sellers are talking about when they discuss things like wattles and spurs. We provide that info in this section of the chapter.

Checking out the differences

Chicken body parts may vary in looks, but almost all chickens have all the body parts we discuss. For example, although comb shape and size can vary, both by breed and sex, all chickens have a comb. One exception to chickens having the same body parts is the lack of a tail in Araucana chickens and some chickens that are mixed with them. No one quite knows why; it’s just another mutation that man has chosen to selectively breed.

Another interesting difference is that some breeds have four toes and some have five. When a breed has an extra toe, it always points to the back. All chickens have two legs. All chickens have feathers, too, although the look of the feathers can vary.

Externally, male and female chickens have the same parts. You can’t sex a chicken by looking under the tail. But males (roosters) usually have some exaggerated body parts, like combs and wattles (we define those shortly), differently shaped feathers on the tail and neck, and an iridescent coloration to the feathers of the tail, neck, and wings that females (hens) generally lack. Roosters are also slightly heavier and taller than hens of the same breed.

When you look at a healthy, live chicken, you see several different parts. In this section, we discuss these parts from the head down, and Figure 2-1 provides a visual representation. We note the differences in the external appearance of males and females, as well as some looks that are peculiar to certain breeds along the way.

Honing in on the head and neck

The most significant parts of a chicken’s head are the comb, the eyes and ears, the beak and nostrils, and the wattles and the neck. The following sections provide a closer look at each of these parts, from the head down.

The comb

At the very top of the chicken’s head is a fleshy red area called the comb. The combs of Silkie chickens, a small breed, are very dark maroon red. Both male and female chickens have combs, but they’re larger in males.

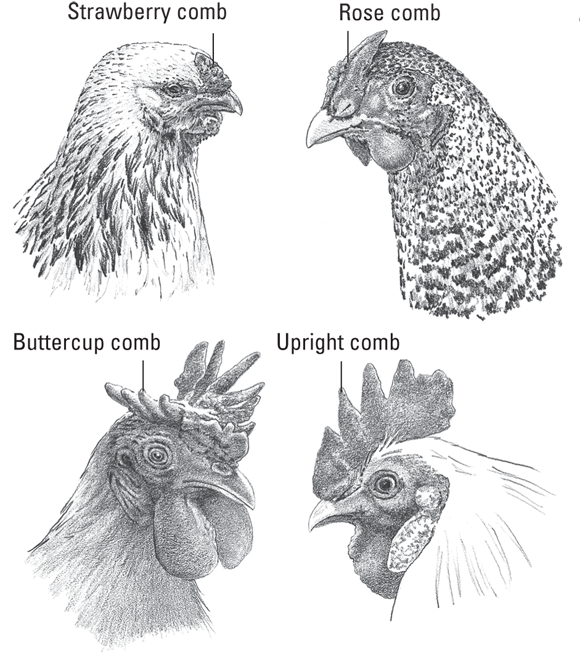

Baby chicks hatch with tiny combs that get larger as they mature. The shape of the comb may not be totally apparent in a young chicken, but you should be able to tell whether the comb is upright, rose-combed (a crumpled-looking comb tight to the head), or double. See Figure 2-2 for examples of various types of combs.

Different breeds have different types of combs. Depending on the breed, the comb may be floppy, upright, double, shaped like horns, or crumpled and close to the head.

These differences in combs are a result of breeders selecting for them. Chicken breeds with small combs close to the head were often developed in cold countries. Large combs are prone to frostbite in cold weather, and parts of them may turn black and fall off. Conversely, large, floppy combs may help chickens cool down in hot, humid weather.

The comb acts like the radiator of a car, helping to cool the chicken. Blood circulates through the comb’s large surface area to release heat. The comb also has some sex appeal for chickens.

Illustration by Barbara Frake

FIGURE 2-2: Some different types of chicken combs.

The eyes and ears

Moving on down the head, you come to the chicken’s eyes. Chickens have small eyes — yellow with black, gray, or reddish-brown pupils — set on either side of the head. Chickens, like many birds, can see colors. A chicken has eyelids and sleeps with its eyes closed.

Chicken ears are small openings on the side of the head. A tuft of feathers may cover the opening. The ears are surrounded by a bare patch of skin that’s usually red or white. A fleshy red lobe hangs down at the bottom of the patch. In some breeds, the skin patch and lobe may be blue or black. The size and shape of the lobes vary by breed and sex.

If a chicken has red ear skin, it generally lays brown eggs. If the skin patch around the ear is white, it usually lays white eggs. A chicken may occasionally have blue or black skin elsewhere, but the skin around the ear will still be red or white. This coloring can help you decide whether a mixed-breed hen will lay white or brown eggs, if that’s important to you.

Three breeds lay blue or greenish eggs: the Araucana, the Ameraucana, and the Easter Eggers. Those breeds have red ear-skin patches.

The beak and nostrils

Chickens have beaks for mouths. Most breeds have yellow beaks, but a few have dark blue or gray beaks. The lower half of a chicken’s beak fits inside the upper half of the beak. When the bird is breathing normally, you should not see a gap where daylight shows between the beak halves. Also, neither beak half should be twisted to one side.

A bird’s beak is made of thin, hornlike material and functions to pick up food. Beaks are present on baby chicks, and a thickened area on the end of the beak, called the egg tooth, helps them chip their way out of the eggshell. Chickens also use their beaks to groom themselves, running their feathers through their beaks to smooth them.

Chickens don’t have teeth, but inside the beak is a triangular-shaped tongue. The tongue has tiny barbs on it that catch and move food to the back of the mouth. Chickens have few taste buds, and their sense of taste is limited.

At the top of the beak are the chicken’s two nostrils, or nose openings. The nostrils are surrounded by a raised tan patch called the cere. In some birds, the nostrils may be partially hidden by the bottom of the comb. Birds with topknots have much larger nostril caverns. The nostrils should be clean and open. A chicken’s sense of smell is probably as good as a human’s, according to the latest research.

The wattles and the neck

Under the beak are two more fleshy lobes of skin, one on each side. These are called the wattles. They’re larger in males, and their size and shape differ according to breed. The wattles are usually red, although in some breeds, they can be blue, maroon, black, or other colors.

The neck of the chicken is long and slender. It’s made for peeking over tall foliage to look for predators. The neck is covered with small, narrow feathers, called hackle feathers, that all point downward. See the section “Finding out about feathers,” later in this chapter, for more info.

Checking out the bulk of the body

A chicken’s body is rather U-shaped, with the head and tail areas higher than the center. The fleshy area from beneath the neck down to the belly is called the breast. Some breeds — generally those that are raised for meat — have plumper breasts. Birds, of course, do not have mammary glands.

The area of the back between the neck and the tail is called the saddle. Saddle areas can be colorful in male birds. Wings attach to the body on both sides, just below the neck. Chicken wings have a joint in the center, and the bones are shaped a lot like human arm bones.

Finally, you come to the tail. Wild male chickens carry their tails in a slight arch, but the tails tend to be narrow and long, to better slide through the underbrush where the wild chicken lives. Many domesticated male chickens have been bred with exaggerated tail arches; wide, fanlike tails; and extremely long tail feathers, although some breeds have no tail feathers. Male tail feathers are often very colorful. The rooster’s tail has no effect on his function, and tail feather differences were selected by man just for show.

Hens, or female chickens, tend to have small tails, either in a fan-type pattern or in a narrow arch pattern. The feathers may be the same color as the body or a contrasting color, but they’re not as colorful as the male’s.

Looking at the legs and feet

Most chickens have four toes, each of which has a nail. Three point toward the front, and one points to the back. Some breeds have a fifth toe. This toe is in the back, just above the backward-pointing toe, and does not touch the ground. It usually curves upward. All chickens also have a spur, although it’s very small in most hens. A spur is like a toe that doesn’t touch the ground; instead, it sticks straight out of the back of the chicken’s leg. It’s hard and bony. Roosters may have large, sharp spurs. Hens rarely have large spurs, and if an old hen gets a bigger spur, they are still smaller than a roosters. Roosters use their spurs for defense and fighting.

Checking out chicken skin

The skin of most chickens is yellow or white, with the exception of the Silkie, which has black skin under all feather colors, and the Egyptian Fayoumis, which has slate-colored skin. The color of a chicken’s feathers does not determine the color of the skin. The color of chicken skin can be influenced by what the chicken eats. In chickens that eat a lot of corn and chickens that free-range and eat a lot of greens, yellow skin is a darker, more golden color; white skin turns creamy.

The flesh of chickens is thin, loose, and easy to tear. The feathers grow from follicles all over the chicken’s skin. In one breed, the Turken, no feathers grow on the neck. Some think Turkens look like turkeys, but they’re not crossed with turkeys.

The lower part of the leg is covered with thick, overlapping plates of skin, called scales. As chickens age, the skin on the lower leg looks thicker and rough. Many breeds of chickens have yellow legs, regardless of skin or feather color, but some breeds have white, gray, or black legs.

Finding out about feathers

Feathers cover most of the chicken’s body. Most breeds of chickens have bare legs, but some have feathers growing down their legs and even on their toes. Other variations of feathering include muffs, puffs of feathers around the ear lobes; beards, long, hanging feathers beneath the beak; and crests or topknots, poofs of feathers on the head that may fall down and cover the eyes.

Some breeds of chickens appear fluffy, and some appear smooth and sleek. Chickens with smooth, sleek feathers are called hard-feathered, and birds with loose, fluffy feathers are called soft-feathered.

A feather mutation can cause the shaft of the feather to curl or twist, making the feathers on the bird stick out all over in a random fashion. Talk about your bad hair day! These birds are called Frizzles. The Frizzle mutation can occur in a number of chicken breeds.

Birds shed their feathers, beginning with the head feathers, once a year, usually in the fall. This shedding period is called the molt, and it takes about 7 weeks to complete. The molt period is stressful to chickens. We discuss molt later in this chapter and in more detail in Chapter 10.

Types of feathers

Contour feathers are the outer feathers that form the bird’s distinctive shape. They include wing and tail feathers and most of the body feathers.

Down feathers are the layer closest to the body. They provide insulation from cold temperatures. Down feathers lack the barbs and strong central shaft that the outer feathers have, so they remain fluffy. Silkie chickens have body feathers that are as long as the feathers of normal chickens, but their outer feathers also lack barbs, so the Silkie chicken looks furry or fluffy all over.

Feathers also vary according to what part of the chicken they cover. The following list associates these various types of feathers with the chicken’s anatomy:

- On the neck: The row of narrow feathers around the neck constitutes the hackles. Hackle feathers can stand up when the chicken gets angry. These feathers are often a different color than the body feathers, and they may be very colorful in male birds. In most male chickens, the hackle feathers are pointed and iridescent. Female hackle feathers have rounded tips and are duller.

- On the belly and midsection: The belly and remaining body areas of the chicken are covered with small, fluffy feathers. In many cases, the underside of the bird is lighter in color.

- On the wings: Chickens have three types of feathers on the wings. The top section, closest to the body, consists of small, rounded feathers called coverts. The middle feathers are longer and are called secondaries. The longest and largest feathers are on the end of the wing and are called primaries. Each section overlaps the other just slightly.

- On the legs: Chicken thighs are covered with soft, small feathers. In most breeds, the feathers end halfway down the leg, at the hock joint. In some breeds, however, the legs have fluffy feathers right down to and covering the toes.

- On the tail: Roosters have long, shiny, attractive tail feathers. In many breeds, the top three or four tail feathers are narrower and may arch above the rest of the tail. These are called sickle feathers. Hens have tail feathers, too, but they are short and plainly colored, and they don’t arch.

Anatomy of feathers

Feathers are made of keratin, the same stuff that comprises your fingernails and hair. Each feather has a hard, central, stemlike area called a shaft. The bottom of the mature shaft is hollow where it attaches to the skin and is called a quill. Immature feathers have a vein in the shaft, which will bleed profusely if the feather is cut or torn.

Immature feathers are also called pinfeathers because when they start growing, they are tightly rolled and look like pins sticking out of the chicken’s skin. They are covered with a thin, white, papery coating that gradually wears off or is groomed off by the chicken running the pinfeather through its beak. When the cover comes off, the feather expands. When the feather expands to its full length, the vein in the shaft dries up.

Chickens can lose a feather at any time and grow a new one, but new feathers are more plentiful during the molting period. The age of a chicken has nothing to do with whether a feather is mature.

On both sides of the shaft are rows of barbs, and on each barb are rows of barbules. The barbules have tiny hooks along the edge that lock them to their neighbors to make a smooth feather. When chickens preen themselves, they are smoothing and locking the feather barbs together.

Feathers grow out of follicles in the chicken’s skin. Around each feather follicle in the skin are groups of tiny muscles that allow the feather to be raised and lowered, allowing the bird to fluff itself up.

The color of feathers comes both from pigments in the feather and from the way the keratin that forms the feathers is arranged in layers. Blacks, browns, reds, blues, grays, and yellows generally come from pigments. Iridescent greens and blues usually come from the way light reflects off the layers of keratin. The way the light reflects off the feather is similar to the way light reflects off an opal or pearl. Male chickens generally have more iridescent colors.

A Picture of Health

Although we cover chicken health more carefully in Chapter 10, we briefly discuss what a healthy chicken looks like in this section. Having this information may keep you from mistaking illness or deformity for the normal appearance of a chicken.

Following are some quick pointers for determining whether a chicken is healthy and normal:

- Eyes: Chicken eyes should be clear and shiny. When a chicken is alert and active, its eyelids shouldn’t be showing. You shouldn’t see any discharge or swelling around the eyes.

- Nose: Both nostrils should be clear and open, with no discharge from the nostrils.

- Mouth: The chicken should breathe with the mouth closed, except in very hot conditions. If cooling the bird doesn’t make it breathe with its mouth closed, it is ill.

- Wings: The wings of chickens should be carried close to the body in most breeds. A few breeds have wings that point downward. (You need to study breed characteristics to see what is normal for your breed.) The wings shouldn’t droop or look twisted. Sometimes droopy wings are a sign of illness in the bird. A damaged wing that healed wrong won’t affect the laying or breeding ability of the bird. However, some birds are hatched with bad wings, which is usually the result of a genetic problem. These birds should not be used for breeding.

Feathers: In general, a chicken shouldn’t be missing large patches of feathers. Hens kept with a rooster often have bare patches on the back and the base of the neck near the back. These patches are caused by mating and are normal. You should never see open sores or swelling where the skin is bare. Sometimes feathers are pulled out, particularly tail feathers, when capturing a bird. If the bird appears healthy otherwise and the skin appears smooth and intact, it’s probably fine.

A healthy bird has its feathers smoothed down when it is active. Some breed differences are noteworthy — for example, obviously, a Frizzle with its twisted feathers will never look smooth. A bird with its feathers fluffed out that isn’t sleeping or taking a dust bath is probably ill.

- Feet and toes: The three front toes of chickens should point straight ahead, and the feet should not turn outward. The hock joints shouldn’t touch, and the toes shouldn’t point in toward each other. Chicken feet shouldn’t be webbed (webbing is skin connecting the toes), although occasionally webbed feet show up as a genetic defect. You shouldn’t see any swellings on the legs or toes. Check the bottom of the foot for swelling and raw, open areas.

- Vent: The feathers under the tail of the chicken around the vent, the common opening for feces, mating, and passing eggs, should not be matted with feces, and you shouldn’t see any sores or wounds around it.

- Mental state: The chicken should appear alert and avoid strangers if it is in a lighted area. Birds that are inactive and allow easy handling are probably ill. Chickens in the dark, however, are very passive, and this is normal.

- Activity level: Here again, differences exist between breeds, but a healthy chicken is rarely still during the daylight hours. Some breeds are more nervous and flighty; others are calm but busy. In very warm weather, all chickens are less active.

On Chicken Behavior

Watching a flock of chickens can be as entertaining as watching teenagers at the mall. Chickens have very complex social interactions and a host of interesting behaviors. And like most domesticated animals, chickens prefer to be kept in groups. A group of chickens is called a flock.

Knowing a little about chicken behavior is crucial to keeping chickens. In this section, we briefly discuss some typical chicken behaviors so you can decide whether the chickens you are keeping are normal or just plain crazy.

Hopefully, knowing a little bit about chicken behavior may sway you if you’re sitting on the fence about whether to raise chickens. Raising chickens is a fun hobby, even if you’re raising them for serious meat or egg production. When the power goes out, you can go back to the times of your forefathers: Sit out on the porch and watch the chickens instead of TV.

Processing information

Being called a birdbrain is supposed to indicate that you’re not very smart. Bird brains may be organized more like reptile brains than mammal brains, but plenty of evidence indicates that birds, including chickens, are pretty smart. Scientists have recently discovered that while the “thinking” area of a bird’s brain may look different from the same part of a mammal’s brain, birds are capable of thought processes that even some species of mammals can’t achieve. And chickens’ brains are able to repair a considerable amount of damage, something mammal brains can’t do.

Birds, including chickens, understand the concept of counting and can be trained to count items to achieve an award. Most mammals who are said to count are actually responding to signals from the trainer. Birds also trick or deceive other birds, and even other animals, which means they must be able to understand the outcome of a future or planned action.

Some birds also mimic the sounds of other birds and animals; few other animals mimic sounds. Chickens, however, cannot be taught to talk as some bird species can, and they don’t mimic other animals. Chickens probably fall about midrange on the intelligence scale of birds.

Chicken brains have a large optic area because vision is very important to their survival. A chicken can spot a hawk or hawklike object from a good distance away, and the brain immediately tells the chicken to run for cover or freeze, whichever will be most effective. They also learn to spot and avoid other predators quite quickly. We have known chickens that actually differentiate between different dogs and know whether they’re friends or foes.

Chicken eyes are also adept at spotting the tiniest seed or the slightest movement of a bug. We have seen them pick up ant eggs and pick the seed off a bit of dandelion fluff. While human eyes can miss an expertly camouflaged tomato hornworm, even a big fat one, beady chicken eyes quickly spot it.

Communication

Chickens are very vocal creatures, and they communicate with each other frequently. Chickens are rarely quiet for long unless they are sleeping. The range of sounds that chickens make is wide and somewhat open to human interpretation, but we’ve attempted to define some of the sounds as follows:

- Crowing: The loud “cock-a-doodle-do” a rooster makes is the chicken noise most people know best. Roosters crow when they become sexually mature, and they don’t do it just in the morning. The crow announces the rooster’s presence to the world as ruler of his kingdom: It’s a territorial signal. Different roosters have different crows — some are loud, some softer, some hoarse sounding, some shrill, and so on. Roosters crow all day long.

- Cackling: Hens make a loud calling noise after they lay an egg. Many times other hens join in. It can go on for a few minutes. Some people call it a signal of pride; others say it’s a yell of relief!

- Chucking or clucking: Both roosters and hens make a “chuck-chuck” or “cluck-cluck” sound as a conversational noise. It occurs at anytime and can be likened to people talking among themselves in a group. Who knows what they discuss?

- Perp-perping: Roosters make a soft “perp-perp” noise to call hens over to a good supply of food. Hens make a similar noise to alert their chicks to a food source.

- Rebel yelling: Hey, it’s hard to describe these noises, but chickens give out a loud holler of alarm when they spot a hawk or other predator. All the other chickens scatter for cover.

- Growling: All chickens can make a growling noise. Hens commonly make this noise when they’re sitting on eggs and someone disturbs them. It’s a warning sound and may be followed by an attack or a peck.

- Squawking: Grab or scare a chicken of either sex, and you’ll probably hear this loud sound. Sometimes other chickens run when they hear the noise, and other times they’re attracted, depending on the circumstances.

- Other noises: The preceding sounds are only some of the more common chicken noises. Baby chicks peep, hens make a sort of crooning sound when they’re nesting, and some hens seem to be humming when they’re happy and contented. Roosters make aggressive fighting noises. Sit around a chicken coop long enough, and you’ll hear the whole range of sounds.

Table manners

Chickens are notorious for eating almost anything. Their taste buds are not well developed, and tastes that we consider bad don’t faze them. This can be their downfall if they eat something like Styrofoam, paint chips, fertilizer, or other things that look like food to them. Good chicken-keepers need to protect their charges from eating things like pesticide-coated vegetation, plastic, Styrofoam beads, and other harmful items.

Chickens eat bugs and worms, seeds and vegetation, and meat. They can’t break bones into pieces, but they will pick the meat off them. We’ve seen them eat snakes and small mice. They will pick through the feces of other animals for edible bits, and they’ll scratch up the compost pile looking for choice nuggets.

It takes only about 2½ hours for food to pass completely through a chicken’s digestive system. The food a chicken picks up in its beak is first sent to the crop, a pouchlike area in the neck for storage. The crop is stretchy and allows the chicken to quickly grab sudden food finds and store them for a slower ride through the rest of the digestive system. From the crop, food passes to the stomach, where digestive enzymes are added.

You may also notice chickens picking up small rocks or pieces of gravel, sometimes called grit. These go into the gizzard, just beyond the stomach, and help the chicken break down food like human teeth do. When chickens roam freely, they get plenty of grit for digestion. If confined, you may need to provide it — we discuss that in Chapter 8.

Both male and female chickens actively hunt for food a good part of the day. Hens sitting on eggs are an exception: They leave the nest for only brief periods of time to feed. Chickens that are confined still go through the motions of hunting for food, scratching and picking through their bedding, and chasing the occasional fly. If food is plentiful, chickens may rest in the heat of the day or stop to take a dust bath. Chickens don’t eat at night or when they’re in the dark.

Most breeds of chickens are equally good at finding food given the chance, with a few exceptions. The large, heavy, broiler-type meat birds are like sumo wrestlers — they prefer to park their huge bodies in front of a trough and just sit and eat. They don’t do well if they have to rustle their own chow or if their food doesn’t consist of high-energy, high-protein items.

Sleeping

When chickens sleep, they really sleep. Total darkness makes chickens go into a kind of stupor. They’re an easy mark for predators at this point; they don’t defend themselves or try to escape. If you need to catch a chicken, go out with a flashlight a couple hours after darkness has fallen, and you should have no problem, providing you know where they roost. Chickens also sit still through rain or snow if they go to sleep in an unprotected place.

Because they’re vulnerable when they sleep, chickens prefer to roost (perch) as high off the ground as they can when sleeping. The more “street-savvy” birds also pick a spot with overhead protection from the weather and owls. Chickens like to roost in the same spot every night, so when they’re used to roosting in your chicken coop, they’ll try to go back home at nightfall even if they’ve managed to escape that day or are allowed to roam.

Socializing

With chickens, it’s all about family. If you don’t provide chickens with companions, they will soon make you part of the family. But chickens have very special and firm rules for all family or flock members. Chickens in the wild form small flocks, with 12 to 15 birds being the largest flock. Each wild flock has one rooster.

Ranking begins from the moment chicks hatch or whenever chickens are put together. Hens have their own ranking system, separate from the roosters. Every member of the flock soon knows its place, although some squabbling and downright battles may ensue during the ranking process. Small flocks make chicken life easier. In large flocks of 25 or more chickens and more than one rooster, fighting may periodically resume as both hens and roosters try to maintain the “pecking order.”

The dominant hen eats first, gets to pick where she wants to roost or lay eggs, and is allowed to take choice morsels from the lesser-ranked hens. The second-ranked hen bows to none but the first, and so on. In small, well-managed flocks with enough space, the hens are generally calm and orderly as they go about their daily business.

Roosters establish a ranking system, too, if there’s more than one in a flock. A group of young roosters without hens will fight, but generally an uneasy truce based on rank will become established. Roosters in the presence of hens fight much more intensely, and the fight may end in death for one of the roosters. If more than one rooster survives in a mixed-sex flock, he becomes a hanger-on — always staying at the edge of the flock and keeping a low profile.

If you have a lot of hens and a lot of space, such as in a free-range situation, each rooster may establish his own separate flock and pretty much ignore the other rooster except for occasional spats. How aggressive a rooster is depends on both the breed and the individuals within a breed. We’ve had some very aggressive roosters, to the point that they’ve been a serious nuisance or even a danger to the human caretaker. When a rooster becomes aggressive toward humans, the best option is the soup pot.

A rooster always dominates the hens in his care. Sorry, no women’s lib in the chicken world. He gets what he wants when he wants it. And what he doesn’t want is a lot of squabbling among his flock. When he’s eating, all the hens can eat with him, and no one is allowed to pull rank. If squabbling among hens gets intense at other times, he may step in and resolve the problem.

A rooster can be much smaller and younger than the hens in the flock, but as long as he’s mature, he’s the ruler of the coop. But it’s not all about terrorizing the ladies. The rooster is also their protector and guide, as well as their lover. He stands guard over them as they feed, shows them choice things to eat (usually letting them have the first bites), and even guides them to good nesting spots.

Roosters tend to have a favorite hen — usually, but not always, the dominant hen in the flock — but they treat all their ladies pretty well. They may mate more frequently with the favorite, but all hens get some attention.

Romance

We’ve established the rooster as the stern but loving protector of his family; now we talk about chicken romance, or the mating process. Roosters have a rather limited courtship ritual, compared to some birds, and the amount of “romancing” varies among individuals, too.

When a rooster wants to mate with a hen, he usually approaches her in a kind of tiptoelike walk and may strut around her a few times. Usually a hen approached this way crouches down and moves her tail to one side as a sign of submission. The rooster jumps on the hen’s back, holds on to the back of her neck with his beak, and rapidly thrusts his cloaca against hers a few times. He then dismounts, fluffs his feathers, and walks away. Boastful crowing may also take place soon after mating, although crowing is not reserved just for mating. The hen stands up, fluffs her feathers, and walks away as well. Both may preen their feathers for a few minutes after mating.

A young rooster may mate several hens within a few minutes of each other, but usually mating is spread out throughout the day. A rooster may mate a hen even if he’s infertile: Fertility drops as roosters age, and cold weather also causes a drop in fertility.

The celibate hen — living without a rooster

Hens don’t need a rooster to complete their lives — or even to lay eggs, for that matter. A hen is hatched with all the eggs she’s ever going to have, and she’ll lay those eggs for as long as the hen lives (or until she’s out of eggs), whether a rooster is around or not. The number of eggs a hen lays over her lifetime varies by breed and the individual. After the third year of life, though, a hen lays very few eggs.

Of course, without a rooster, no babies will be hatched from those eggs, but the eggs that we eat for breakfast don’t need to be fertilized to be laid. Hormones control the egg cycle whether a rooster is present or not. And fertilized eggs don’t taste differently — nor are they more nutritious — than unfertilized eggs.

Is a hen happier with a rooster around? Our guess is that she probably is because it fits the more natural family lifestyle of chickens. But hens are pretty self-sufficient, and our guess is that if they’ve never known life with a rooster, they really don’t know what they’re missing.

New life

At about the time an egg is to be laid, usually early in the morning, hormone levels in the hen rise, and she seeks out a nest and performs some nest-making behaviors: moving nest material around with her beak, turning around in the nest to make a hollow, and sometimes gently crooning a lullaby. Several hens may crowd into a nest box at one time, and they seem to be stimulated by the laying of hens around them.

After the egg is laid, hormone levels generally drop, and the hen hops off the nest and announces her accomplishment with a loud cackling sound. Other hens may join in the celebration. Morning is a noisy time in the henhouse. After laying an egg, the hen generally goes about her daily routine.

A hen that does have the instinct to sit on (incubate) eggs and hatch them and is in the mood to do so is called a broody hen. Many modern breeds of chickens no longer incubate eggs because the maternal instinct has been bred out of them. Thus, the eggs need to be artificially incubated (put in an incubator) to perpetuate those breeds. The instinct was bred out of them because when a hen is sitting on a clutch of eggs or raising her young, she doesn’t lay eggs.

When a hen does go broody, she tries to sneak off and hide her eggs in a secret nest. If she can’t, she commandeers one of the nest boxes in the coop. The hen lays about ten eggs before she starts sitting in earnest. Fertilized eggs are fine in their suspended animation stage until she decides to sit. The reason the hen doesn’t start sitting on the eggs until about ten have built up is that nature intends for the chicks to hatch all at once so the mom will have an easier time caring for them. It takes 21 days for eggs to hatch.

We discuss the egg formation process in more detail in Chapter 15, and we discuss both natural and artificial incubation processes in Chapter 13.

When the chicks have hatched, their mom leads them out into the world, showing them how to eat and drink and defending them to the best of her ability. At night or when it’s cold, the chicks snuggle under her for warmth. A hen can be very aggressive when defending her young, and many tales are told about hens giving their lives to defend their babies. Chicks stay with the mom at least until they’re feathered, and often for 4 or 5 months.

Bath time

Another interesting behavior of chickens is their bathing habits. They hate getting wet, but they sure do love a dust bath. Wherever the coop has loose soil — or even loose litter — on the floor, you will find chickens bathing.

Chickens scratch out a body-sized depression in the soil and lie in it, throwing the soil from the hole into their fluffed-out feathers and then shaking to remove it. They seem very happy when doing this, so it must feel good. In nature, this habit helps to control parasites.

In the garden or lawn, these dust-bath bowls can be quite damaging, but you can’t do much about it except put up a fence. If your chickens are confined all the time, they’ll really appreciate a box of sand to bathe in.

Interacting with Other Poultry and Animals

The previous section discusses how chickens socialize with each other, but many new chicken owners want to know how chickens interact with other poultry or animals. Many people envision a happy barnyard mixture of chickens and other poultry, or perhaps goats and horses. You can have that peaceful environment, in most cases, if you have some knowledge of how chickens interact with other animals.

In this section, we give some general guidelines for interspecies interaction. Individual animals can vary in how tolerant they are. It’s up to the chicken owner to carefully supervise animal introductions and intervene when an animal is in danger.

Dogs and cats

Dogs and chickens often don’t mix well. In fact dogs can be a chicken-keeper’s worst enemies — even your own dog. (It’s your dog we talk about here; we discuss the neighbor’s dog more in Chapter 9 when we cover fending off predators.)

We think that people can own both dogs and chickens (we own both) if some basic precautions are taken. Be very careful introducing dogs to chickens, even small dogs. Terriers and hunting breeds may be more likely to kill chickens but any breed or mix of breeds is capable of doing harm. Never leave dogs alone with chickens until you have observed the dog interacting with the chickens safely many times under various circumstances.

Some dogs simply ignore chickens, but to many dogs, chickens are just fun. They run and squawk, and it’s all very exciting. Even if they don’t catch them, dogs should never be allowed to chase chickens. Being chased is very stressful to a chicken: In their minds, a dog is the same as a fox or a wolf. Stressed chickens don’t lay well, aren’t friendly, and get sick more often. You may think it’s cute to see dogs “herding” the chickens, but we assure you, the chickens don’t.

Training a dog that shows interest in chasing or harming chickens rarely works unless the dog is a pup and you are a good and consistent trainer. If your dog wants to chase or, worse, kill chickens, the chickens and dogs must be confined separately or you must consider which animals you really want to own. Confining both the chickens and the dog gives you double protection. Dogs will often climb over fences or dig under them if they are excited so plan accordingly. Electric wire or “hot wires” at the top of a good fence and 8 to 12 inches from the ground at the fence bottom will almost always keep dogs inside and are an easy way to secure large areas for dogs. The electric fence setups can be found at any farm store and they won’t seriously harm the dog. Invisible fences set ups for dogs won’t work to separate dogs from chickens because the chickens won’t get a shock when they cross the line and may wander into the dog’s reach.

Cats don’t usually pose a risk to adult chickens. They will kill and eat chicks, however, so you need to protect the chicks from them. Wait to introduce cats to chickens until the chickens are full grown. Barn cats usually learn at a young age to avoid chickens because adult chickens can be very mean to kittens. Most barn or outside cats will simply ignore chickens. Cats often go hunting for mice and rats in chicken areas, but only rarely will a feral cat kill a chicken. Small bantams are most at risk, so we recommend keeping any small valuable bantams in pens that even your own cats can’t get into.

Ducks and geese

In general, ducks and geese get along well with chickens. However, you may need more room than a small backyard to keep them with chickens. Ducks and geese need to be kept where they have a lot of space to roam and a place to bathe. Ducks and geese can also furnish you with edible eggs, but you need to know some info about these combinations.

You can mix ducklings or goslings (baby geese) with chicks in a brooder (a warm, protected spot for baby poultry — see Chapter 14) without them harming each other. However, you’ll need a plan for meals. We usually recommend that chicks start out with medicated feed, but ducklings and goslings shouldn’t have medicated starter feed because they’re sensitive to the antibiotic used. Since you can’t keep them from eating each other’s feed, all the babies will need unmedicated feed. This compromise may then lead to more disease problems in the chicks.

We recommend using a higher-protein feed, such as broiler feed, for ducklings — the chicks will be okay with that choice, too. As adults, ducks, geese, and chickens can eat the same feed, although special feed mixes for ducks are available.

Keep in mind that ducks are messy, even when they’re ducklings. They’ll play in the water, and their droppings are more liquid than chicks, so brooders with ducklings need more frequent cleaning to keep them dry. Ducklings don’t need to swim while in the brooder (although they will if they can fit inside the water container), and it’s not recommended to let them bathe if you’re keeping them with chicks. Goslings aren’t quite as messy with water.

You’ll need to address one other consideration when keeping ducks with chickens. Don’t keep male ducks with chickens without female ducks also being present. Ducks are often aggressive sexually. If they’re deprived of their own females, they may mate with hens. Unlike roosters, male ducks (called drakes) have a penis and may hurt hens. We’ve heard of male geese (ganders) also mounting chicken hens, but it’s much less frequent. We’ve seen roosters mount female ducks, too, but it’s not as common. These matings don’t result in fertile eggs.

Mother hens and ducks sometimes raise each other’s babies when allowed to mingle freely. They may lay in each other’s nests and sit on each other’s eggs. Chicks don’t usually follow a stepmama duck into water, but we have heard of it happening. Baby ducklings can confuse a hen when they pop into water to swim, but it rarely causes a problem.

Turkeys

We’ve kept turkeys and chickens together for many years and don’t have problems with them interacting in a free-range situation. However, when breeding turkeys, having broody chickens around can be a problem. The birds will squabble over nests and disrupt egg incubation. Occasionally, individual turkeys and chickens develop a dislike for each other, and this fighting can cause distress to the other birds. If this happens, you need to separate those individuals.

You can raise baby turkeys (poults) with baby chicks if you remember that the poults need more protein than chicks. You must feed a turkey starter to them (24 to 26 percent protein), or they will develop crooked legs and wings and may die. When the poults are about a month old, we advise separating the turkey poults and regular chicks if the chicks aren’t broiler (meat) chicks (you can leave turkeys with broiler chicks until the broilers are butchered). After they’re separated, you need to feed the growing chickens chick grower (lower protein). See Chapter 8 for more about feeding chickens. Turkeys need a high-protein feed until they finish growing.

Meat turkeys take from 3 to 5 months to reach butchering size; turkeys wanted for breeding and pets are grown at about 6 months. At that time, you can mingle the turkeys and chickens, if you want, and use the same feed as you do for the chickens.

You can use broody hens to hatch turkey eggs, even though incubation for turkey eggs is 28 days (7 days longer than for chickens). Turkeys also occasionally hatch chicken eggs. Either way, the chicks will probably be successfully raised by their step mommas. Turkey eggs can be eaten just like chicken eggs; they’re generally white with brown freckles.

Turkeys and chickens have been known to mate with each other, although it is rare. Sometimes hybrid birds have hatched from these matings, but those birds are sterile.

Guineas

Guinea fowl can be kept successfully with chickens, but they’re much noisier than chickens, and we don’t recommend them when neighbors are close. They also fly well, wander extensively, and like to roost in trees at night.

Adult guineas can eat the same food as adult chickens. Baby guineas can be raised with chicks, but they should have a higher-protein feed, such as broiler chicken feed, of about 20 to 24 percent protein.

Guineas and chickens have mated with each other in rare circumstances and produced sterile offspring.

Pheasants and quail

In general, we don’t recommend mixing pheasants and quail with chickens. As babies, these birds are fragile and require game bird starter as feed. As adults, they’re often aggressive, particularly some pheasant breeds, and often kill chickens. We find that pheasants and quail tend to make chickens act wilder when kept together.

Chickens are sometimes used to hatch pheasant or quail eggs and can raise the babies successfully. Pheasants rarely mate with chickens and, when they do, produce sterile offspring.

Livestock

With the exception of pigs, it’s mostly up to individual animals how chickens and large livestock interact. Pigs will eat chickens they can catch, and it’s highly recommended that you keep chickens away from pig pens. Cattle, sheep, goats, and horses can occasionally be mean to chickens, but usually they ignore them.

Chickens will pick through manure to eat maggots and undigested food. This practice is great fly control, but if it disgusts you, keep the chickens out of pastures and stalls. It doesn’t affect the taste or safety of chicken eggs, by the way.

People often worry when they see a huge swelling on their chicken’s throat. That swelling is generally a full crop, meaning that the chicken has just been a little greedy, much like a chipmunk when it fills its cheeks. Over a few hours, the “swelling” subsides as food in the crop is passed along the digestive system.

People often worry when they see a huge swelling on their chicken’s throat. That swelling is generally a full crop, meaning that the chicken has just been a little greedy, much like a chipmunk when it fills its cheeks. Over a few hours, the “swelling” subsides as food in the crop is passed along the digestive system. Be aware that, with the exception of Muscovy ducks, ducks and geese can be noisy, and neighbors may not welcome them.

Be aware that, with the exception of Muscovy ducks, ducks and geese can be noisy, and neighbors may not welcome them.