Chapter 9

Working with More Complex Texts

The truism has it that children “first learn to read, and then read to learn.” Your third grader can decode, so presumably it’s time to “read to learn.” That catchphrase is a bit deceptive however, as it simplifies what is actually a quite serious increase in the expectations for comprehension.

What’s Happening at School

“Read to learn” makes comprehension sound so straightforward, but by this point, you know that comprehension rests on three factors:

Note that all three are characteristics of either the text or of the reader. That is, a writer can make a text more comprehensible by using simple vocabulary and straightforward syntax, and by assuming little background knowledge on the part of the reader. If the writer doesn’t do these things, the reader is not completely defenseless. The reader can look up words she doesn’t know, she can expend more mental effort to untangle difficult syntax, and (although this one is tougher) she can try to find the knowledge that’s necessary to make appropriate inferences. But before the reader will do that extra work, she must first recognize, “Hey, I don’t understand this.”

Noticing When Comprehension Fails

How hard can it be to perceive that you don’t understand what you’re reading? Students are not as good at this work as you might think. They notice if a word is not in their vocabulary. They notice if they don’t understand the syntax of a sentence. But they don’t always connect the meaning of sentences, and they don’t notice that they fail to do so. That’s especially true of poor readers, who are satisfied with a fairly minimal understanding of a text; when something goes wrong with their comprehension, they often don’t try to solve the problem. It’s not that they are unable to make appropriate inferences. Have them watch an engrossing movie, for example, and they will draw inferences to understand each scene and will think about how scenes fit together so they can follow the plot. But when they read, they figure that if they know most of the words and understand individual sentences, then they are doing their job (figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1. Movies require complex inferences. A ten-year-old who can follow a complex movie plot should be able to read a comparably complex text, provided he can decode well.

I know it seems strange and the research showing this phenomenon would almost be funny if not for the pathos. For example, in one experiment, sixth graders were asked to read essays at the request of an experimenter who told them she needed help to make the essays clearer for children. The essays contained ideas that contradicted one another. Sometimes the contradictions were subtle, as in this example:

In other essays, the contradiction was made very explicit:

Remarkably, when the error was subtle, sixth graders noticed it no more than 10 percent of the time. Even when it was made terribly obvious, no more than half noticed it.

Reading Comprehension Strategies

What would happen if you told students, “Hey, you should really try to tie the meaning of sentences together?” And while we’re at it, we can tell them that their background knowledge will be helpful in making those connections and that they must evaluate whether the connections they are drawing seem to make sense. These are the core ideas behind reading comprehension strategies, a mainstay of reading education in upper elementary school and beyond. You don’t just tell students to “tie the meaning of sentences together,” because that’s a bit vague. Instead you give them more concrete tasks—tasks that can’t be completed unless you connect the sentences.

Here’s a list of commonly taught reading comprehension strategies. (You won’t be quizzed on them, so feel free to skim.)

Note that these reading comprehension strategies encourage students to do exactly what we said is required for comprehension. Strategies 1 and 2 are designed to get students monitoring their comprehension. Strategies 3 and 4 are meant to get students to relate their prior knowledge to what they read. And strategies 5 through 11 require relating sentences in the text to one another.

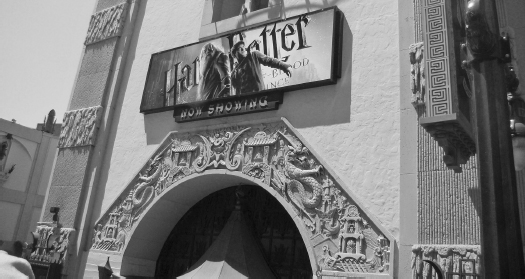

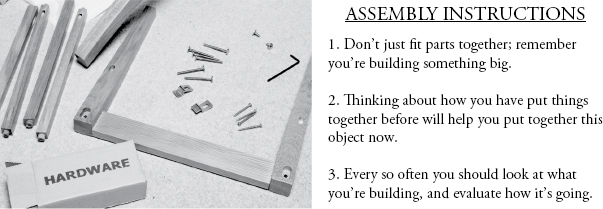

If you’re an experienced reader, these strategies may seem like unnecessary complications (figure 9.2). Nevertheless, teaching these strategies to students is supported by research. Here’s the way a typical experiment works. You administer a reading test to some students, say, fourth graders. Then you teach them a reading comprehension strategy. Most often, you wouldn’t teach them just one: you’d teach a combination of perhaps three. Over the course of a few weeks, you’d have a number of sessions (from as few as ten to as many as fifty or more) in which you’d model how to use the strategies and the students would practice. The sessions might be daily or a few times per week. At the end of the experiment you would administer a reading test again and see whether comprehension has improved. (You’d compare the improvement to a control group of students who were not taught the strategy.)

Figure 9.2. Do adults use reading strategies? Who sits down at the breakfast table and thinks, “Ah, here’s a headline about Ukraine. Let me activate my background knowledge about Eastern Europe in preparation to read this article”? Of course, it’s possible that I used to use these strategies, but after years of reading, they’ve become automatic and I don’t notice that I use them.

Source: © Daniel Willingham.

Many studies show that teaching strategies improves reading comprehension, and the gains are by no means trivial. The exact size of the boost is complicated to calculate, but even the low estimates have this relatively brief intervention—as short as a few weeks—moving a child reading at the 50th percentile up to the 64th percentile.a

A Little Is Enough

The documented benefit of reading comprehension strategy instruction is impressive given its modest cost, yet this instruction is easy to overdo. Teaching reading strategies does work, but the benefit comes after just a few sessions, and it doesn’t get any bigger with more practice.

Here’s how we know that. Suppose you looked at fifty experiments that had taught kids reading comprehension strategies. In some experiments, kids got just a few lessons in how to use them. In other experiments, kids got more practice. You would expect that more practice would lead to bigger gains in reading. But it doesn’t. Just a few sessions—five or ten—give the same benefit as fifty. That finding, which several researchers have observed, is hard to square with the idea that reading comprehension strategies directly improve comprehension. We have this idea that comprehension is a skill, like hitting a baseball, and comprehension strategies are like things that the coach tells you: “Keep your eye on the ball,” “Your hips provide the power of the swing,” and so on. We practice these strategies, and our skill improves.

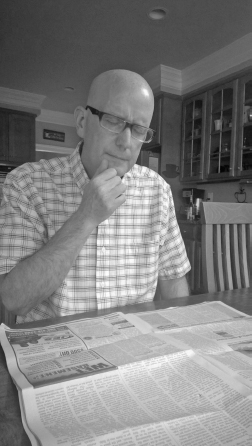

But remember how comprehension works. It depends on the particular content of sentences, so it’s not open to that kind of strategic instruction. Here’s an analogy. Suppose that reading is like putting together a piece of furniture you bought at Ikea. Like a text, furniture has parts that must fit together in a particular way, and if you do the job right, all the parts coalesce into something larger—a functional object.

Suppose you lay out all the pieces of your unassembled desk, and find strategy-like instructions (figure 9.3). These instructions don’t tell you how to actually build the piece of furniture. You need to know whether piece A is supposed to attach to piece B or C. Rather, these instructions concern what to think about when you’re executing instructions (the ones that tell you that part A attaches to part B).

Figure 9.3. Furniture assembly strategy instructions.

Source: © Joe Gough—Fotolia.

Reading comprehension strategies are similar. They tell you what to do: monitor your comprehension, relate prior knowledge to what you’re reading, relate sentences in the text to one another. They don’t tell you how to get those things done. They can’t, because how to do them depends on the particulars. Comprehension requires relating sentence A to sentence B, but I can’t give you generic instructions about how to relate them. Their relationship depends on the contents of sentence A and sentence B.

For someone who thinks that assembling furniture is merely a matter of attaching pieces to one another for a while, this big-picture overview is good advice. Likewise, if a child doesn’t appreciate that the purpose of reading is communication and that she’s meant to understand what she reads, comprehension strategy instruction is a great idea. For example, a student who has difficulty decoding may view decoding as synonymous with reading. Decoding is really taxing, so if I’m decoding, then I’m doing my job. Reading comprehension strategy instruction tells the child, “Decoding is not enough. You are supposed to understand what you’re reading. Just as you do when you listen to a story, when you read, you must relate the beginning, middle, and end.”

A New Demand: Working with Texts

The National Assessment of Educational Progress, more commonly known as the “Nation’s Report Card,” defines “basic” fourth-grade reading skill as the ability to “locate relevant information, make simple inferences, and use their understanding of the text to identify details that support a given interpretation or conclusion.” In other words, comprehension is no longer defined as understanding the text. Comprehension means being able to use the text to aid reasoning. And of course texts become longer and more complex with each grade. If that weren’t enough, upper elementary and middle school is when teachers often start to expect that students will do more reading independently at home, so that class time can be devoted to other things.

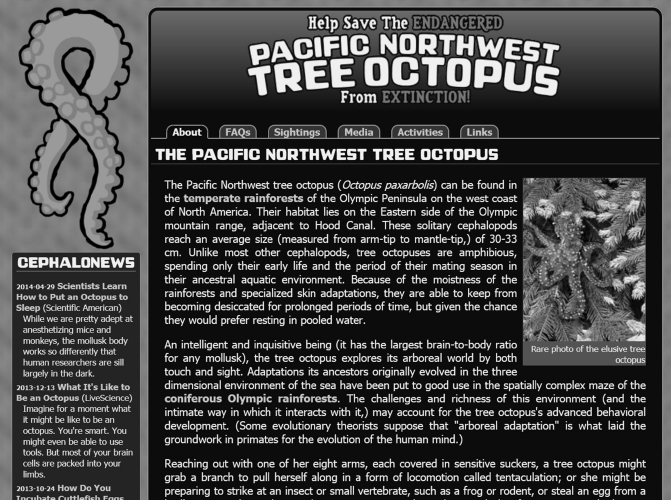

Later, in high school, students may learn that researchers in different disciplines treat texts differently. It’s not just that researchers know different things and are interested in different facets of a text. Each discipline has norms about what’s interesting and important. For example, sourcing is fundamental to a historian’s work: Who wrote this text, with what goal in mind, and for what audience? Scientists care little, if at all, about sourcing or the author’s perspective. But budding scientists must learn how scientific journal articles are structured: what goes into the methods section, what sort of speculation is permissible in the discussion section, and so forth. As students learn more about a discipline, they learn what merits special attention according to the conventions of the discipline and what is secondary (figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4. Historic letter. This is the first page of a letter from Albert Einstein to President Roosevelt about the possibility of developing atomic bombs. This letter would be read in different ways by a historian, a scientist, and a theologian.

Source: WikiMedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Einstein_Szilard_p1.jpg.

“Comprehension” comes to mean different things as students get older. Initially it means no more than “understand the story.” Later, we want students to put texts to other purposes: find facts for research, memorize information for a test, or analyze the author’s technique to persuade or evoke emotion. Students who were strong readers in early grades may find themselves challenged as they had not been before by these tasks.

Most of this work happens at school, not at home, but it’s useful for parents to have it on their radar. You want to be aware that your child is taking on these new tasks and to ensure that he is getting the proper instruction and support at school. The teacher may assume that students have learned something—how to use reference materials, for example—in an earlier grade, when in fact your child never received that instruction. (That’s obviously a greater risk if you switched schools.) It’s best to be in touch with your child’s teacher so that you know what she’s doing in class and can ask how you can support this work at home.

Digital Literacy

Some education commentators have suggested that we need to think of “reading comprehension” differently, because it (along with writing and other aspects of literacy) has been so profoundly changed by the broad availability of digital technologies. The ability to create, navigate, and evaluate information on various digital platforms is generically called “digital literacy.” What should we make of this? Is the idea of “reading comprehension” outdated?

Different aspects of digital literacy need to be evaluated separately. Consider first the idea of a general tech savviness. I think there’s little doubt that exposure to and practice with digital technologies teach kids certain conventions common across these technologies: menuing systems, hierarchical file structures, and the like. This knowledge is important exactly because these conventions are respected across applications and across devices. But they are pretty easy to learn. Software is engineered to be simple to use, and kids learn this stuff rapidly. Some adults like to joke about how helpless they are in the face of these newfangled gadgets compared to kids who seem such naturals. But kids in fact vary widely in their tech knowledge, and age-related differences, when they exist, are not due to limited learning abilities on the part of oldsters; they are due to youngsters’ greater motivation and opportunities to learn from their peers.

The second aspect of digital literacy is the ability to evaluate information. The web is often praised for its effect in democratizing publishing. Twenty years ago, the owners of publishing companies were gatekeepers of information. My comprehensive knowledge of, say, rare animal species in the Pacific Northwest would remain unknown if I could not persuade the gatekeepers to publish it. Now I can publish whatever I like over the web or as an e-book and let consumers decide whether it’s valuable. That’s great, but the gatekeepers did serve a function: most had an interest in ensuring some quality control. Certainly they fulfilled this role imperfectly—falsehoods were and are published by mainstream sources—but as standing institutions, publishers are more accountable than individuals publishing websites on a lark, and their records for accuracy are easier to track. On the web, readers must take greater responsibility for evaluating the reliability of what they encounter.

In the mid-2000s the need for greater student education on this matter gained publicity through a website describing the endangered Northwest Tree Octopus, a fictitious species said to live in trees (figure 9.5). The website deftly mimics the prose used in science textbooks (“Because of the moistness of the rainforests and specialized skin adaptations, they are able to keep from becoming desiccated for prolonged periods of time.”). Aside from the absurdity of a cephalopod living out of water, there are hints scattered throughout that it’s a hoax—for example, the octopus’s main predator is said to be the sasquatch, and the website is endorsed by the organization “Greenpeas.”

Figure 9.5. Tree octopus. A screenshot from the website describing the fictitious tree octopus.

Source: http://zapatopi.net/treeoctopus/.

Yet when researchers at the University of Connecticut asked twenty-five seventh graders to evaluate the site—students named by their schools as their most proficient online readers—every single one fell for the hoax. When they were told that it was false, most struggled to find evidence that could have told them that, and some even insisted that website was legitimate. Other research has shown that students rarely critically evaluate information they find on the web. They probably would be no more critical of a paper pamphlet on the tree octopus; the point is that there is more misinformation on the web than is generated by traditional publishers, and so kids need to be more discerning when reading there.

In the last few years, there have been greater efforts to teach students how to be critical readers of information on the web. Students have been taught techniques like evaluating the author’s credentials, tracing the domain to evaluate whether the website is commercial or originates in the education community, checking how recently the web page was updated, and looking for other websites that have linked back to the target site. Teaching students these evaluation skills is still in its infancy, but thus far it has been tough going. Some studies indicate that it helps students understand the importance of evaluating websites, but their evaluations of websites don’t actually improve.

What to Do at Home

As before, most of what I’ve encouraged you to do by way of making your home knowledge rich and your child knowledge hungry still applies. This age does bring two new concerns. First, most kids begin to spend significant amounts of time with digital devices, so we’ll evaluate what that might mean for acquiring background knowledge. Second, we need to consider strategies you might employ if you think that a lack of background knowledge is impairing your child’s reading comprehension.

Knowledge in the Digital Age

As kids move into middle school, they don’t just spend more time with digital devices; they also change what they do with them. They still watch a lot of video content, but they add video gaming, texting, and surfing the web. What are the consequences of these activities to reading and to background knowledge?

Reading Volume

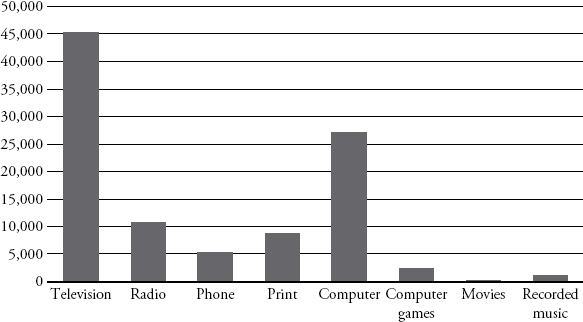

One change wrought by the digital revolution is that kids are actually reading much more than they used to, even though reading is commonly thought to be in decline. A 2009 study at the University of California, San Diego, examined the number of words to which the average American is exposed per day (figure 9.6).

Figure 9.6. Average daily word consumption, by media. Note that the measure is “words,” so they might be spoken, sung, or written.

Source: From “How much information?” by R. Bohn, J. Short, Global Information Industry Center, University of California, San Diego. Data from Appendix B, © UCSD (2009).

The volume of words received by computer is enormous. And although “by computer” includes words read and words heard, when the data were collected in 2008, most Americans did not have Internet access speed adequate for video or audio streaming. Most of the words they received would have been in print. These data were collected from adults, and are now half a decade old. Still, I think it’s reasonable to suggest that kids do an enormous amount of incidental reading on digital platforms, especially in text messages, which this study did not include. So, does all this reading make them better readers?

We don’t have firm data on this question, but reading theory would predict little benefit to comprehension from this type of material. Reading improves comprehension through the acquisition of broader background knowledge, but most of what the average kid reads on screens is not content rich. It’s information within games, text messages, social network updates, and the like. But that sort of reading should (according to theory) have a positive effect on fluency. That prediction has not been tested as far as I know.

Knowledge Everywhere

Wait a minute. How can I be so sure that kids are not benefiting from this increase in reading? Doesn’t it depend on what they are reading? You can read anything online, from a Shakespeare concordance to pornographic satire of The Hunger Games series.

Although we can say with wide-eyed innocence, “Hey, they could be reading Shakespeare,” we suspect otherwise. One wag put it this way: “I possess a device, in my pocket, that is capable of accessing the entirety of information known to man. I use it to look at pictures of cats and get in arguments with strangers.” Survey data confirm that teens use computers for a relatively limited number of activities. The most common are

- Social networking

- Playing games

- Watching videos

- Instant messaging

This survey is dated (it’s from 1999), but at that time, these four activities accounted for 75 percent of teens’ computer time. Today instant messaging has been replaced by texting, to which the average teen devotes about ninety minutes daily. We can’t generalize to every child, but I don’t think it’s the case that teen use of digital devices is so varied that we cannot make any claims about its likely impact.

Well, perhaps they are not seeking out rich sources of information but find themselves exposed to such information anyway. After all, the hallmark of the digital revolution is that it has made information cheap, in the best sense of the word. You can’t help but get damp if you’re in a flood, and the Internet is a fire hose of information.

Kids could learn in this incidental way, and there’s evidence that they do, at least from certain sources. Toddlers and preschoolers who watch educational television really do learn about numbers and letters, as well as social lessons (e.g., about sharing). But overall, kids learn less from video than you’d think. Infants and toddlers seem to have a harder time learning from video than from a live person, a phenomenon established enough that it is called the “video deficit.”

Mostly, the idea that new technologies leave people more knowledgeable goes unsupported. It might be right, but at the moment, it’s unsupported. For older kids, the relationship between television viewing and academic achievement is negative, not positive; but note, that effect is carried by heavy viewers. Kids who watch only a little TV show no academic cost. (And for all kids, TV content, not just volume, matters.) More generally, kids who report being heavy users of all media (television, music, gaming, and the others) also report getting lower grades—but the relationship of grades and leisure reading is positive. Still, simple correlations like this don’t tell us much about such complex behaviors.

Do We Need to Know Less?

Kids may not choose to read Shakespeare, but they could find information about his life or plays with ease. Those of us who grew up before the digital age truly find it miraculous that we can instantly find the name of the president during the War of 1812, whether jambalaya typically includes shellfish, or how to translate European shoe sizes to American. Whatever you want to know, however obscure, you can find it, and find it almost immediately.

Given the importance I placed in chapter 1 on knowledge as a driver of reading comprehension, we might ask whether easy access to information means that digital technologies render knowledge in one’s head less important for reading (figure 9.7).

Figure 9.7. Marissa Mayer. In 2010 when she was vice president for search products and user experience at Google, Mayer wrote, “The Internet has relegated memorization of rote facts to mental exercise or enjoyment.”a Mayer is now president and CEO of Yahoo!

Source: Photo © Yahoo. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marissa_Mayer_May_2014_%28cropped%29.jpg.

aMayer (2010).

There are three reasons that Googling information (or Yahooing it, or Binging it) is not a substitute for knowledge in your head when you are reading. First, if you recognize that you’re missing something—you realize the writer has omitted some information that you need to make an inference—it’s not always obvious which information is called for. Recall the example from chapter 1: “Trisha spilled her coffee. Dan jumped from his chair to get a rag.” If you don’t have the necessary knowledge in your head to understand why Dan jumped from his chair, you might search for “coffee” on the web. You’re going to find an enormous amount of information: where coffee is grown, social customs around the world about how it’s drunk, different ways to prepare it, and so on. That’s a lot to sort through before you deduce which property the author assumed you knew.

A second problem with tracking down information is that you don’t always know that you’re missing anything. If that happens, it will likely be in the development of the situation model. I illustrated that point with the Carol Harris/Helen Keller story.

Finally, halting reading to find a definition or bit of information is disruptive. The more often you do it, the more likely you are to lose the logical thread of what you’re reading and the more likely you are to quit reading it. So a substantial amount of knowledge needs to be known, not just findable.

When a Lack of Knowledge Hurts Comprehension

What can you do if you feel your child is not reading well because of a dearth of background knowledge? In the previous section, I argued that digital devices don’t much improve knowledge and literacy, at least as kids usually employ them. The information superhighway may somewhere be roaring with frenetic power and speed, but your child has elected to dwell on familiar byways and cul-de-sacs. What other options are open if you feel your middle or high schooler lacks the broad background knowledge needed for effective reading comprehension?

Playing Knowledge Catch-Up

There’s good news and bad news here. The good news is, as with fluency, that it’s never too late. Sometimes you’ll hear a news story about brain plasticity in early childhood that makes it sound as if there is a window of opportunity for learning in the early years that, if missed, means your child is out of luck. Not so. You can always learn. The bad news is that there is not a shortcut. Vocabulary and knowledge of the world accrete slowly, over the course of years. If there is an easy way to hurry it, scientists haven’t found it.

And honestly, it’s probably not useful to think of it as “catching up.” You want your child to read more. Period. Yes, background knowledge helps, but that’s in service of your child reading a wider variety of materials and enjoying them more. So meet him where he is, bearing in mind the big-picture goal. More reading, more fun. Not catching up.

Catching Up by Resetting the Starting Line

Your eighth grader might not be able to read a story written at an eighth-grade reading level, but the content and themes of books written for fourth graders will not be appealing. A possible solution is a book written to the tastes of older kids—the characters are their age, their relationship problems mirror theirs—but the books are written with simpler vocabulary and sentence structure. There are comparable nonfiction books. These books are called “hi-lo,” short for “high interest, low reading level” (figure 9.8). (I list some publishers in the “Suggestions for Further Reading” section at the end of this book.)

Figure 9.8. Hi-lo books. These books are so named because they contain high-interest content at a low reading level. The two books shown here are written at a third- or fourth-grade reading level but appeal to high schoolers. Note that the covers are meant to look age appropriate.

Another approach is to find reading material on a subject that your child knows a lot about, thus circumventing the knowledge gap. A good choice is a book for which your child already knows the story. If he sees a movie he loves, see if it was based on a book or if a novelization has been published. If he loves a television show, a book of trivia and backstage gossip about the show might work. See if there is fan fiction written about a movie your child loves. (Fan fiction is a genre of new stories, written by fans, based on characters from an established television show, movie, or book. They are readily available on the web.) If your child is obsessed with an actor, find a biography. If it’s a singer, find a book of song lyrics.

This reading material may strike you as trivial, but the goal is to get your child to think of leisure reading as a viable option. Thus, we’re brushing up against the question of motivation. In the next chapter we’ll tackle motivation in older kids head-on.

Notes

“That’s especially true of poor readers, who are satisfied with a fairly minimal understanding of a text”: Long, Oppy, and Seely (1994); Magliano and Millis (2003); Yuill, Oakhill, and Parkin (1989).

“It’s not that they are unable to make appropriate inferences.”: Johnston, Barnes, and Desrochers (2008).

“in one experiment, sixth graders were asked to read essays at the request of an experimenter”: Markman (1979).

“studies show that teaching strategies improves reading comprehension”: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2000).

“Just a few sessions—five or ten—give the same benefit as fifty.”: Elbaum, Vaughn, Tejero Hughes, and Watson Moody (2000); Rosenshine, Meister, and Chapman (1996); Rosenshine and Meister (1994); Suggate (2010).

“they learn what merits special attention according to the conventions of the discipline”: Shanahan and Shanahan (2008).

“differences, when they exist, are not due to limited learning abilities on the part of oldsters”: Bennett, Maton, and Kervin (2008); Margaryan, Littlejohn, and Vojt (2011).

“when researchers at the University of Connecticut asked twenty-five seventh graders”: Leu and Castek (2006).

“students rarely critically evaluate information they find on the web”: Killi, Laurinen, and Marttunen (2008).

“but their evaluations of websites don’t actually improve”: Zhang and Duke (2011).

“examined the number of words to which the average American is exposed per day”: Bohn and Short (2009).

“‘I use it to look at pictures of cats and get in arguments with strangers.’”: Nusername (2013).

“these four activities accounted for 75 percent of teens’ computer time”: Rideout, Foehr, and Roberts (2010).

“preschoolers who watch educational television really do learn”: D. R. Anderson et al. (2001); Ennemoser and Schneider (2007); Mares and Pan (2013).

“the ‘video deficit’”: Deocampo and Hudson (2005); Troseth, Saylor, and Archer (2006).

“TV content, not just volume, matters”: For a review, see Guernsey (2007).

“but the relationship of grades and leisure reading is positive”: Rideout et al. (2010).