Chapter 10

The Reluctant Older Reader

I’ve already noted that reading motivation declines steadily as children age, reaching its lowest point by about grade 10. In this chapter, we consider strategies that teachers and parents might employ to arrest the slide.

What’s Happening at School

In a nutshell, the problem of motivation is this: We want the child to do something we think is important but she chooses not to do it. That is, of course, a very common problem in classrooms. The typical motivator is punishment. A student who doesn’t do the required work is punished by low grades, or perhaps the feeling of disappointing the teacher, or even feeling ashamed should the failure become public. But by the time a child is in middle school, these blades have long lost their edge. Most unmotivated readers have the self-assurance to persuade themselves that reading is not all that important. Schools are not enthusiastic about punishment in any event, so many turn to rewards as motivators.

Rewards

We want the child to read, and we want reading associated with a positive experience . . . well, what if I told a fourth grader, “If you read that book, I’ll give you an ice cream sundae.” The child might take me up on the deal, and it sounds like he’d have a positive experience. So won’t he then then be motivated to read? It sounds so simple that it might be too good to be true (figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1. Book it button. Pizza Hut has conducted its Book It! program since 1984. Each month from October to March, if the child meets a reading target set by the teacher, he gets a certificate for a personal-size pizza. When he cashes in the certificate, the restaurant gives him a sticker to put on his Book It button. There are surprisingly few studies of the long-term impacts of the program on reading attitudes or habits.

Source: Circa 1995 © Tim Stoops.

The Science of Rewards

Rewards do work, at least in the short term. If you find a reward that the child cares about, he will read in order to get it. But what we’re really concerned about is the reading attitude. When you stop giving the reward, will the attitude be more positive than when you began? Research indicates that the answer is often no. In fact, the attitude is often less positive because of the reward.

The classic experiment on this phenomenon was conducted in a preschool. A set of attractive markers appeared during free play, and the researchers affirmed that kids chose the markers from among many activities. Then the markers disappeared from the classroom. A few weeks later, researchers took kids, one at a time, into a separate room. They offered the child a fancy “good player” certificate if she would draw with the markers. Other kids were given the opportunity to draw with the markers but were not offered the certificate. A few weeks later, the markers reappeared during free play in the classroom. The kids who got the certificate showed notably less interest in the markers than the kids who didn’t get the certificate. The reward had backfired: it had made kids like the markers less.

The interpretation of the study rests on how kids think about their own behavior. The rewarded kids likely thought, “I drew with the markers because I was offered a reward to do so. Now here are the markers but no reward. So why would I draw with them?” There have been many studies of rewards in school contexts, and they often backfire in this way (figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2. The effects of rewards. Another example of how a reward changes your thinking about why you do something: people are often less likely to help a friend when offered a reward. If I ask you to help me move my couch, you probably perceive it as a social transaction; your reason to help me out is that you like to see yourself as helpful. But if I say, “I’ll give you five dollars to help me move my couch,” I’ve turned it into a financial transaction, and five dollars may not seem like enough money for the work.

Source: © Anne Murphy.

Note: For a readable review of these sorts of phenomena, see Ariely (2009, chap. 4).

We can imagine that rewarding kids for reading could work as intended in certain circumstances. What if the child has such a positive experience while reading that it overwhelms his thinking that he’s reading only for the reward? In other words the child thinks, “Gosh, I started this book only to get that ice cream sundae, but actually it’s awesome. My teacher was a sucker to offer me a sundae as a reward!” That’s great when it does happen—and I think it can—but it means that rewards represent a risk. We’re gambling that the book is going to be a big hit.

We might hope that a reward could do some good using another mechanism: that it would work like the bedtime-snuggle works—the child already likes ice cream (or whatever the reward is), and pairing it often enough with reading makes the good feeling of eating ice cream become associated with reading. The problem is that the child might consciously think, “I hate reading, but I like ice cream, so I guess I’ll put up with reading.” Researchers have examined whether that sort of conscious thought prevents the warm association from building, but the data are not clear.

What about praise instead of a reward? Generally praise is motivating to kids: they will do more of whatever was praised. But praise can go wrong if it’s overly controlling (“I’m so glad to see you reading. You really should do that every day.”) or if the child thinks it’s dishonest (“You are the best reader at school.”). But if the praise seems like sincere appreciation, it’s motivating. And one of the advantages of praise is that it lacks the disadvantage of rewards. Rewards are usually set up in a bargain before the action: if you read, you’ll get ice cream. Praise is generally spontaneous. You don’t promise praise contingent on good behavior. That means that the praised child won’t think, “I did that only to get the praise,” the way that the rewarded child thinks, “I did that only to get the reward.” The praised child elected to engage in the desired behavior of her own accord, and then the praise came spontaneously. The problem is that the child must choose to read on her own before you get a chance to praise her.

Rewards in Practice

As I’m sure is clear by now, I’m not a big fan of school-based rewards for reading. That includes public classroom displays of reading achievement—for example, posting on a bulletin board the number of books each student has read, or adding a segment of a class bookworm for each book. To my thinking, it puts too much emphasis on having read rather than on reading. Some students (I was one) will pick easy books to boost their “score.” And as a way to recognize student achievement, it doesn’t account for student differences; for some, getting through a book in a month may be a real achievement, yet they will feel inadequate compared to their peers. Some more formal programs (like Accelerated Readera and Pizza Hut’s Book It) try to make up for some of the problems inherent in a reward system. Different books are allocated different points based on difficulty, for example, or different students get different teacher-set reading targets.

Still, I think it’s a mistake to be so absolutist as to say rewards should never be used. Instead I’m suggesting they not be the first thing teachers try, and I want them to be aware of the research literature that describes the potential drawbacks. I know that some districts tune Accelerated Reader or another program to their own use, ignoring the points, for example. The research literature on Accelerated Reader in particular is, in fact, mixed. Much appears to depend on how it is implemented.

I’m also keeping in mind a conversation I had with a district administrator. Kids in her schools come from very poor homes, and she told me that they are not growing up seeing their parents read. A benefactor started a program whereby children earn cash for reading books, and the administrator felt that it was helpful. Kids had not been reading, the rewards got them started, and they discovered they really liked to read. I think it would be high-handed and naive to suggest that the district stop the program. In fact, this seems exactly the situation to try rewards: when you can’t otherwise get a toehold, a way to get kids to at least try pleasure reading. The child may then discover that she likes it, and even when the rewards stop, she keeps going.

But if rewards are to be a last resort, as I’m suggesting, what ought to be tried first?

Pleasure Reading

Our goal is that children read because they feel the pleasure of reading; rewards were meant to be a temporary incentive to get the process going. Another way to frame the problem is this: kids are already feeling the pleasure of reading, but that feeling gets lost in less positive feelings—feelings created by the other demands of schoolwork.

Academic versus Pleasure Reading

We expect students to feel the joy of reading when they get lost in a narrative or feel the pleasure of discovery when reading nonfiction. But as I noted in chapter 9, this is the age at which we add other purposes to reading. One is learning: the student is expected to read a text and study it so that he can reproduce the information (e.g., on a quiz). A second purpose is to help complete a task—a project, say—and that usually entails gathering information. A third purpose is to analyze how a text works, that is, how the author writes to make the reader laugh or cry. I’ll use the umbrella term academic reading to contrast these purposes with pleasure reading.

My concern is that kids might confuse academic reading with reading for pleasure. If they do, they will come to think of reading as work, plain and simple. Sure, we’d like to think that academic reading is pleasurable, but in most schools, “pleasure” is not a litmus test. The student who tells the teacher, “I tried reading that photosynthesis stuff, but it was too boring,” will not be told to find something else she’d prefer. Academic reading feels like work because it is work. But pleasure ought to be the litmus test for reading for pleasure.

I think it’s a good idea for teachers to communicate these distinctions to students—not that “most of the reading we’re doing is academic, and therefore not fun,” but that reading serves different purposes and that there is a distinction between academic reading and pleasure reading.

In some classrooms, pleasure reading is segregated from academic reading: we read because we love reading, and then we also learn how to work with texts. But the way that pleasure reading is handled can still send a silent message to students that reading is work. Coercion sends that message. I’ve warned against requirements that children read a set number of minutes per day at home or that a pleasurable activity be withheld until the child has completed his reading. The same goes for school. If a teacher makes pleasure reading a requirement (ten minutes per night, say) or demands accountability (by keeping a reading log, for example) students may think she believes that they would not read of their own accord.

Pleasure Reading in Class

I’ve said rewards shouldn’t be off the table but also shouldn’t be the first thing that schools try, and I’ve said coercion has drawbacks. What’s left? I think the best strategy is the one that is successful at home: make reading expected and normal by devoting some proportion of class time to silent pleasure reading. A lot of what goes into a typical elementary reading program is not reading; in one study of six basal reading programs, researchers found that student reading averaged just fifteen minutes each day out of a reading block that averaged ninety minutes.

Successful programs for silent classroom reading tend to have certain elements in common:

Setting aside time in the classroom for silent pleasure reading is the best solution I can see for a student who has no interest in reading. It offers the gentlest pressure that is still likely to work. Everyone else is reading, there’s not much else to do, and a sharp-eyed teacher will notice those who are faking it. Freedom of choice also allows the greatest possibility that when the reluctant reader does give a book a try, he’ll hit on something that he likes.

Given that I’m recommending this practice, you probably think there must be good research evidence that it boosts motivation. In truth, I’d say the latest data indicate that it probably improves attitudes, vocabulary, and comprehension. A lot of the research was not conducted in the best way, and the best experiments don’t always support the practice.

I think the squishiness of the findings is attributable to the difficulty of the teaching method. I’m sure classroom pleasure reading is easy to implement poorly: stick some books in the room, allocate some class time, and you’re done. But think of the teacher’s responsibilities when it’s done well. She must help students select books that they are likely to enjoy. That means really knowing each child, and a middle school teacher likely has more than one hundred students. If a teacher is going to be able to confer with students about what they have read, she needs to have read the book herself. Hence, she needs comprehensive knowledge of the literature appropriate to the grade level. And although I’ve said that silent pleasure reading is a good way to gently persuade reluctant students to give reading a try, let’s not pretend this is easy. A sixth grader who believes that reading is boring has a pretty firm sense of herself as decidedly not a reader; a teacher must be a skilled psychologist to get around that attitude and get the student open to reading.

The skills and knowledge demanded of the teacher are one obstacle. A more serious one may be the attitude of some parents and administrators. If you walked into a sixth-grade classroom and saw the students sitting around reading novels, would you think that the teacher was kind of taking it easy? Would you think that the students were learning anything? Don’t be that parent.

Other Features of Great Reading Classrooms

Silent pleasure reading is not a literacy program. If it’s present at all, it will be just part of your child’s day. If you visit your child’s class, what else might you see as part of a classroom that will aid reading motivation?

Teachers who motivate readers are skilled in setting classroom activities that students find engaging and require reading if they are to be completed. Middle and high school students often hunger for school work that is less abstract and more related to their interests or to current events. It takes an inventive teacher to create lesson plans that account for this interest, and are rigorous, and meet school or district curriculum requirements. For example, I met a middle school science teacher who got his students interested in testing surface water quality in the neighborhood around the school. The students liked the possibility that their findings would have practical significance to the people living nearby, and it made them much more open to tackling challenging reading in science reference books.

Second, as in younger grades, teachers who motivate reading are those who avoid praising performance (“you read that really well”) or student characteristics (“you’re an excellent reader”). As with reward, praise offered for performance makes the student focus on performance and worry about errors, and ultimately it may lead him to choose work that will not stretch his abilities in order to ensure good performance that will earn praise. Better options are to praise a student for sticking with a difficult task or picking a book from a genre she had never tried before.

Third, teachers who motivate are not controlling. It’s hard for students to be engaged when they know they have no voice in whatever comes next. Classrooms offer many opportunities for teachers to unwittingly control their students, for example, by talking too much, giving hyperdetailed instructions, interrupting students, or making decisions that seem arbitrary. In contrast, students are more likely to be motivated if their teacher listens to them, shows concern about student interests, acknowledges when work is challenging, and explains why work is being undertaken.

What to Do at Home

On the early side of this age range—the elementary years through middle school—much of what I’ve said in previous chapters about getting younger kids reading is still applicable, with some minor adjustments that I am guessing I don’t need to spell out. But the challenge is different for middle and high schoolers. Compared to a nine-year-old, a fourteen-year-old has many more opportunities to avoid that home environment that you’ve tried to shape as a literary oasis, and they have a much stronger sense of themselves as “not a reader” or “a reader.” In chapter 9 I mentioned that older children use more types of digital technologies. They also have greater access to them.

Are Gadgets Killing Reading?

Most of the parents I talk to are convinced that digital devices are having a profound and mostly negative impact on reading. The research on this issue is more limited than you might guess, because we’re predicting a long-term consequence of the use of digital technologies and these technologies haven’t been available that long. That said, I think the digital age is having a negative effect on motivation, but not through the mechanism that most parents fear.

Concentration Lost

A lot of teachers think that kids today are easily bored, and they blame digital devices for making them that way. Why are they to blame? Some observers—including prominent reading researcher MaryAnn Wolf—have suggested that habitual web reading, characterized by caroming from one topic to another and skimming when they alight, changes the ability to read deeply. Nick Carr popularized this sinister possibility with the question: “Is Google Making Us Stoopid?” In that article (and in a follow-up book, The Shallows), Carr argued that something had happened to his brain. Years of quick pivots in his thinking prompted by web surfing had left him unable to read a serious novel or long article (figure 10.4). This does sound similar to the mental change many teachers feel they have seen in their students in the last decade or two; they can’t pay attention, and teachers feel they must do a song and dance to engage them.

Figure 10.4. Does multitasking affect the brain? Trying to do two or things simultaneously demands frequent shifts in attention and could—the theory goes—exacerbate the web-generated tendency to read by skimming.

Source: © david goehring via Flickr.

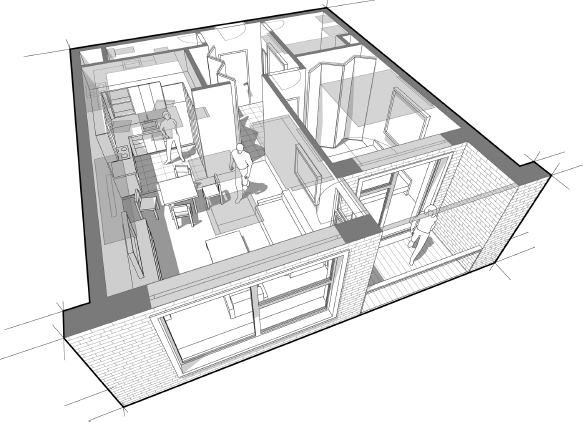

I doubt that reading on the web renders us unable to concentrate, and although a formal poll has not been taken, I suspect most cognitive psychologists are in my camp. Yes, video games and surfing the web change the brain. So does reading this book, singing a song, or seeing a stranger smile. The brain is adaptive, so it’s always changing. If it’s adaptive, couldn’t that mean that it would adapt to the need for constant shifts in attention, and maybe thereby lose the ability to sustain attention to one thing? I don’t think so, because the basic architecture of the mind probably can’t be completely reshaped. Cognitive systems (vision, attention, memory, problem solving) are too interdependent for that. If one system changed in a fundamental way—such as losing the ability to stay focused on one object—that change would cascade through the entire cognitive system, affecting most or all aspects of thought. The brain is probably too conservative in its adaptability for that to happen (figure 10.5).

Figure 10.5. The architecture of the mind. The adaptability of the mind may be compared to a home’s floor plan, where each room is like a cognitive process. You can expand or shrink rooms without affecting the overall design, but trying to move the living room from the front of the house to the back—a major reorganization—would be very disruptive.

Source: © Slavomir Valigursky—Fotolia.

More important, I don’t know of any good evidence that young people are worse at sustaining attention than their parents were at their age. Teens can sustain attention through a three-hour movie like The Hobbit. They are capable of reading a novel they enjoy like The Perks of Being a Wallflower. So I doubt that they can’t sustain attention. But being able to sustain attention is no guarantee that they’ll do so. They also have to deem something worthy of their attention, and that is where I think digital technologies may have their impact: they change expectations.

I’m Bored. Fix It

Despite the diversity of activities afforded by digital technologies, many do have two characteristics in common. First, whatever experience the technology offers, you get it immediately. Second, producing this experience requires minimal effort. For example, if you’re watching a YouTube video and don’t like it, you can switch to another. In fact, the website makes it simple by displaying a list of suggestions. If you get tired of videos, you can check Facebook. If that’s boring, look for something funny on TheOnion.com. Watching television has the same feature: cable offers a few score of channels, but if nothing appeals, get something from Netflix (figure 10.6).

Figure 10.6. Omnipresent entertainment. You have diversion in your pocket, so there is never a reason to be bored, even in the few minutes that these people are waiting for the Metro in the Washington, DC, area.

Source: © Jeffrey, via Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/jb912/6483730553/in/photolist-aSWPcP-dqq4jD-fSELGZ-6DYhtp

The consequence of long-term experience with digital technologies is not an inability to sustain attention. It’s impatience with boredom. It’s an expectation that I should always have something interesting to listen to, watch, or read and that creating an interesting experience should require little effort. In chapter 4, I suggested that a child’s choice to read should be seen in the context of what else she might do. The mind-boggling availability of experiences afforded by digital technologies means there is always something right at hand that one might do. Unless we’re really engrossed, we have the continuous, nagging suspicion there’s a better way to spend my time than this. That’s why, when a friend sends a link to a video titled, “Dog goes crazy over sprinkler—FUNNY!” I find myself impatient if it’s not funny within the first ten seconds. That’s why my nephew asked me, “Why do I check my phone at red lights, even though I know I haven’t received any important messages?” That’s why teachers feel they must sing and dance to keep students’ attention. We’re not distractible. We just have a very low threshold for boredom.

If I’m right, there’s good news; the distractibility we’re all seeing is not due to long-term changes in the brain that represent a pernicious overhaul in how attention operates. It’s due to beliefs—beliefs about what is worthy of sustained attention and about what brings rewarding experiences. Beliefs are difficult to change, true, but the prospect intimidates less than repairing a perhaps permanently damaged brain.

Some people focus less on cognitive changes wrought by digital technologies and more on behavior, specifically the raw amount of time they consume. How can one have time for anything else, including reading? Isn’t it inevitable that people will read less if they devote more time to things other than reading?

The Displacements

There’s no time for reading! This idea is not new. It’s called the displacement hypothesis, and though it comes in several varieties, the basic idea is that when a new activity (like browsing the web) becomes available, it takes the place of something else we have typically done (like reading). Evaluating whether that’s true is tricky because lots of factors go into our choices. For example, if you simply ask the question, “Does television displace reading?” you’re thinking that if it does, you’d expect a negative correlation: more TV goes with less reading, and less TV goes with more reading. But the wealthier you are, the more leisure time you have. So even if television does bite into reading time, we may not see the data pattern we expect because both activities are facilitated by free time.

So has reading been displaced by digital technologies? On balance, the answer seems to be no, although most of the research in this country has focused on adults, not children. Researchers have examined correlations between time spent on the Internet and time spent reading, statistically controlling for other variables like overall amount of leisure time as well as could be done. The correlation in most studies seems to be nil or slightly positive (in the direction opposite that predicted by the displacement hypothesis). Research on television viewing does indicate that heavy viewing (more than four hours each day) is associated with less reading.

Given the enormous amount of time devoted to digital technologies, how is it possible that they don’t shove reading aside? One answer is that most people read so little there isn’t much to be shoved aside. In 1999, when they had virtually no access to digital technologies (outside of gaming), children (ages eight to eighteen) spent an average of just twenty-one minutes per day reading books. In 2009, when access was much greater, they averaged twenty-five minutes. These data are a little deceptive, however, because they are averages. It’s not that every child in 1999 read for about twenty-one minutes. Rather, some read quite a bit and some (about 50 percent) didn’t read at all. So for half of kids, there was no chance for digital technologies to displace reading.

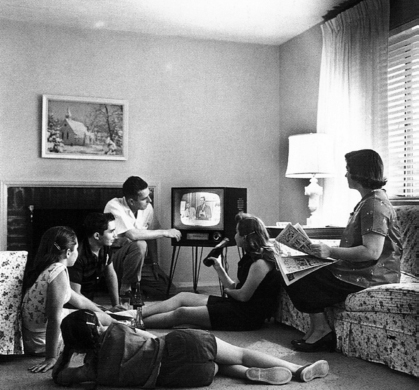

For the kids in 1999 who did read, it may be that reading provides a sort of pleasure that digital technologies don’t replace. They like the fun that digital technologies provide, but it’s a different sort of fun than they get from reading. Notably, magazine and newspaper reading did drop during the decade that followed, arguably because that sort of reading can be done on the Internet (figure 10.7).

Figure 10.7. How television affected reading. When television became widely available in the 1950s, both reading and radio use dropped, but not across the board. People read less light fiction because television offered light drama. People saw television news coverage as thin, so they still read newspapers. This pattern of data led to the functional equivalence hypothesis: an activity is more likely to displace another if it better serves the same function. If it serves a different function, it’s less likely to displace it.

Source: Wikimedia. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Family_watching_television_1958.jpg.

So I’m offering a mixed message. Good news: I doubt digital activities are “changing kids’ brains” in a scary way, and I don’t think they soak up reading time. Bad news: I think they are leading kids to expect full-time amusement, and for some kids, reading time isn’t soaked up only because there’s little to soak up. It’s already dry as a sun-bleached Saltine.

Positive Steps

The preceding section leads to a rather glum conclusion. But don’t despair. There are positive steps you can take, even with a sulky teen, that might tempt him to read.

Shatter Reading Misconceptions

Danny Hoch has written and produced one-man performance pieces that have won two Obie awards. In an interview, he described one theater-goer’s reaction to his one of his shows:

I think a lot of students have similar attitudes about reading. “Reading” means books written by dead people who have nothing to say that would be relevant to your life. Nevertheless, you are expected to pore over their words, study them, summarize them, analyze them for hidden meaning, and then write a five-page paper about them. That’s reading. It’s not contemporary. It doesn’t have characters you can identify with. It’s not nonfiction. It’s not magazines or graphic novels.

What would your child find interesting? In chapter 9 I suggested you look for content with which your child is already familiar as a way of getting around a dearth of background knowledge. That makes sense from a motivational standpoint too, but if you are less worried about the knowledge angle, you might branch out by seeking a book with less familiar content but related to her interests. For example, my niece (along with millions of other teens) got interested in forensic science through the television show CSI.

When it comes to fiction, seek books that look fun. Remember that one factor that goes into the choices we make is an assessment of how likely we are to actually get the pleasure that the choice might afford. A thick book with small print looks intimidating to less-than-confident readers. Go for books that have short chapters or go for graphic novels, which look easy because of the pictures. (But be advised, many are challenging.) Kids in mid- to late-elementary school might appreciate a collection of a comic strip they enjoy. And older kids may be interested in manga (pronounced mayn-ga), a variety of comic from Japan. Manga are published in just about every genre you can think of: adventure, mystery, horror, fantasy, and comedy, but note, mature themes (sexuality, violence) are not rare (figure 10.8).

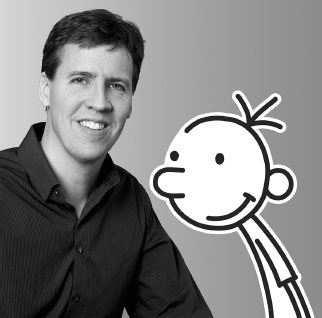

Figure 10.8. Jeff Kinney, author of Diary of a Wimpy Kid. Kinney didn’t intentionally write his books for reluctant readers, but the response from kids who previously disliked reading has been overwhelming. Kinney’s books are wonderfully written and wonderfully funny, but the graphics are doubtless an important part of what makes them inviting.

Source: Picture of Jeff Kinney reprinted with permission of the author.

Another source to consider are websites like Wattpad and Inkpop. These operate a bit like social networking sites in that users “follow” people who post content. Users can also upvote content they like and comment on it. On these sites, the content is fiction. Amateur writers post stories, hoping to gain an audience. Much of the content is aimed at teens and preteens, and people often serialize their content; they don’t post an entire novel, but rather post a chapter at a time. These bite-size portions might appeal to a reluctant reader—three thousand words is short enough to read on your phone during a bus ride.

It may be that none of this is to your taste. In fact, this sort of reading material may strike you as poorly written and as glorifying aspects of popular culture that you find objectionable. That’s a judgment call, of course. I would not let my kids read material that is misogynistic, racist, or the like. But if my teen avoided all reading, I would be fine with him reading “junk.” Before he can develop taste, he must experience hunger. The first step is to open his mind to the idea that printed material is worth his time. I believe parents will get further toward their own goals by showing curiosity about their children’s interests rather than disdain for them. Taking your child seriously as a reader—by, for example, taking a reading recommendation from him—might make him take himself more seriously as a reader.

Get Help

Let’s be realistic. Each time you hand your child a book and he ends up hating it, he confirms to himself that reading is not for him. Your efforts to persuade him to give reading a try (again) are taxing for both of you, and it’s not the kind of thing you’re going to do every day. So when you do try, you want it to be your best shot. Search “best books for reluctant teen readers” on the web and you’ll find lots of lists. But you need something more fine-tuned to your child. You need someone with deep experience in the process of listening to a child’s interests and tastes (his hobbies, the sort of music he likes, his personality, the subjects he likes and hates at school, the movies he enjoys), and then using that information to find a book maximally likely to intrigue him. Naturally, such a person must have an extensive knowledge of children’s books.

There are two places you might find that sort of person: your school system and your public library. Librarians are a vastly underappreciated resource. They have wide knowledge of and passion for books, and are eager to help. You likely have an expert resource at your public library. Use it!

Finding the most knowledgeable person in your school or district may take a bit of tact. Your child’s teacher is the obvious person to ask about your child’s reading, and certainly you should. But there may be another teacher or reading coach who has made a real specialty of tempting reluctant readers. A suitable compromise might be to start with your child’s teacher. If your gut tells you that her advice may not be enough, thank her and affirm that she’s been helpful but also say that you’re trying to gather as much information as you can, and you wonder whether there’s anyone else she thinks is equally knowledgeable who might have some complementary ideas.

Use Social Connections

How does your child learn about movies he wants to see or video games he wants to play? Advertising. These media have huge budgets to make their product known. Kids also learn about the latest movie from friends—friends who learned about it from omnipresent advertising. Save a few highly successful series, there is no advertising for print material. It’s all word of mouth, and most kids don’t read.

You can try to correct this knowledge deficit directly by telling your teen about content you think she’d like. It probably won’t produce an immediate turnaround, but it may plant a seed in her mind. More effective, though, would be for your child to hear these things from peers. For adults, reading is often social. Part of the success of Oprah’s book club is the feeling of being part of a group—maybe I wouldn’t tackle A Tale of Two Cities on my own, but we’re all in this together. Teens are hypersocial, so reading ought to be social for them as well.

If your child has friends who are readers, great. They are your best allies. More likely she doesn’t, and it’s possible that she is afraid (rightly or wrongly) that her nonreading friends think that reading is nerdy.b This is where technology can help. There are countless book groups on the web—boards where kids discuss books, trade recommendations, post fan fiction, and the like. (You can find examples in the “Suggestions for Further Reading” section at the end of this book.) Your child is not going to dive into one of these communities. The most likely entry point would be through that rare book that does capture her imagination; make sure she knows that there are websites where other enthusiasts discuss the book.

Make It Easy to Access Books

Will an electronic reader help motivation? There are a few scattered studies on this question, showing mixed results. Honestly, I’d be pretty surprised if an e-reader made books sexy to a child who hates reading. As we’ve noted, pleasure reading is not that different on an e-reader. Like their college counterparts, kids (ages nine to seventeen) prefer paper; 80 percent who have experience with e-books say they still read print more often.

Yet these same kids say they think they would read more if they had access to e-books, and I tend to believe them. I don’t think e-readers make reading more fun, once the device has lost its gee-whiz luster. But an e-reader improves access. Being able to download virtually any book you want as soon as you want it (barring cost considerations) is a great advantage. If your child has just finished book two of a trilogy or he’s just heard from a friend about a fantastic new title, that’s when he’s most excited about getting it. But if he has to wait a few days to get to a bookstore or library, his interest may have moved on to something new. Older kids can download an e-reader for their phone. It’s free, and that way they can always have a book with them.

Help Your Child with Scheduling

Some teens like the idea of reading but simply cannot find the time. Activities today do seem much more intense than they were a generation ago; something as seemingly simple as playing soccer or singing in the choir calls for many hours each week. Add in homework, and kids feel that their week is overflowing. How can you help a child who likes the idea of reading find time to do so?

It may not be that your child has no time, but rather that she doesn’t have large blocks of it. She may believe that reading must occur in silence and for some minimum duration. If her teacher says, “Try to read for thirty minutes each night,” it’s easy to see why a student would assume that means thirty consecutive minutes. But adult readers find crumbs of time throughout the day to feed their reading hunger. Your child may simply need to get used to keeping a book with her, to be read in snippets: on the school bus, waiting for a parent to pick her up from her piano lesson, in a long line at McDonald’s. How about an audiobook for her iPod on the ride to school? I like to ask students if they have been bored at any time in the last month. If so, that’s a time they could have been reading.

You might also introduce students to a common strategy we adults use when we’re short of time: we schedule it. You can’t simply hope to find time to do important things—you must make time to do them, and that’s done by consciously selecting a specific time and place that you’ll read. Equally important, your child should anticipate why he wouldn’t read at that planned time. If he plans to read for fifteen minutes at 5:00 p.m. each evening, what might make him decide at that time that he ought to skip reading that day? Or what might interrupt him once he starts? He needs to plan strategies to deal with those interruptions. If he skips reading because he feels panicky about his homework, maybe reading time needs to be rescheduled. If he’s frequently interrupted by his little brother, maybe he needs to choose a more private place to read.

Notes

“The classic experiment on this phenomenon was conducted in a preschool.”: Lepper, Greene, and Nisbett (1973).

“There have been many studies of rewards in school contexts, and they often backfire in this way”: For a review, see Deci, Koestner, and Ryan (1999).

“What about praise instead of a reward?”: For a review of praise, see Willingham (2005).

“The research literature on Accelerated Reader in particular is, in fact, mixed.”: Hansen, Collins, and Warschauer (2009).

“My concern is that kids might confuse academic reading with reading for pleasure.”: For a thorough treatment, see Gallagher (2009).

“just fifteen minutes each day out of a reading block that averaged ninety minutes”: Brenner, Hiebert, and Tompkins (2009).

“As researcher Nell Duke ruefully noted”: Miller and Moss (2013).

“as kids advance through the grades”: Fractor, Woodruff, Martinez, and Teale (1993).

“Some of the most careful experiments indicate that without this feature, students don’t benefit from silent reading time in class.”: Kamil (2008).

“I’d say the latest data indicate that it probably improves attitudes, vocabulary, and comprehension”: Manning and Lewis (2010); Yoon (2002).

“A lot of teachers think that kids today are easily bored, and they blame digital devices for making them that way.”: Richtel (2012).

“prominent reading researcher MaryAnn Wolf”: Rosenwald (2014).

“‘Is Google Making Us Stoopid?’”: Carr (2008).

“follow-up book, The Shallows”: Carr (2011).

“I suspect most cognitive psychologists are in my camp”: Steven Pinker and Roger Schank have both written in this vein: http://edge.org/q2010/q10_10.html#pinker;%20http://www.edge.org/q2010/q10_13.html. See also Mills (2014).

“say they still read print more often”: Robinson (2014).