You love the painting and retouching tools that Photoshop offers; you love layers; you even love all the options it gives you for saving files. But as soon as someone says “alpha channel” or “mask,” your eyes glaze over.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Masks, channels, and selections are actually really easy once you get past their bad reputation. Making a good selection is obviously important when silhouetting and compositing images—two of the most common production tasks. But perhaps even more important, selections are also a key ingredient for nondestructive tonal corrections, color corrections, sharpening, and even retouching. We discussed some of these in the previous chapter, and we’ll explore them further in later chapters. But before we get there, we must first make you a mask maven and a channel champion!

Note that in this chapter we’re only talking about pixel-based selections; we’ll discuss sharp-edged vector clipping paths and masks in Chapter 11, “Essential Image Techniques.”

Back in Chapter 8, “The Digital Darkroom,” we introduced a few concepts that are crucial to becoming a selection expert.

Selections, channels, and masks are actually all the same thing in different forms, and you can convert one to another easily.

A channel is a saved selection and looks like a grayscale image where the black parts are fully deselected (“masked out”), the white parts are fully selected, and the gray parts indicate partially selected pixels.

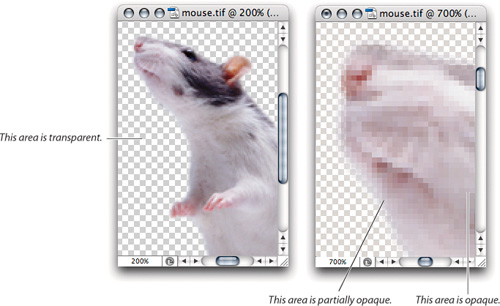

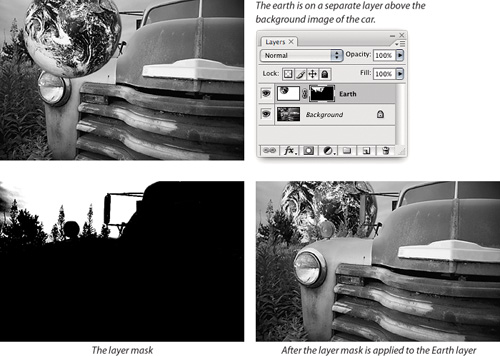

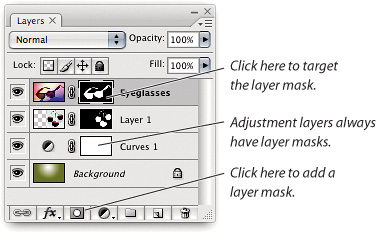

A layer mask is a selection or channel applied to a layer so that the black areas of the mask fully hide the layer and the white areas of the mask are transparent (they show the layer’s pixels). If an area in a layer mask (or channel) is 25 percent gray, then that area is 75 percent visible. Remember: “Black conceals, white reveals,” and the lighter the gray, the more selected or visible the area.

Smooth transitions between selected (white) and unselected (black) areas are incredibly important for compositing images, painting, correcting areas within an image—in fact, just about everything you’d want to do in Photoshop.

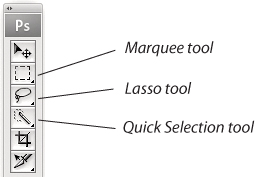

Although there are many ways to make a selection in Photoshop, the selection tools in the Tools palette let you create or fine-tune selections by hand, and for that reason they’ll never go out of style. They fall into distinct groups: the Marquee tool group, the Lasso tool group, and the Quick Selection tool group (see Figure 9-1).

Of course, the little black triangles at the bottom right corner of each tool button let you know that you can hold down the mouse button to reveal more tools. The Marquee tool group contains other tools for basic selection shapes. The free-form Lasso tool contains the Polygonal Lasso tool that draws straight lines and the Magnetic Lasso tool that draws a selection that follows contrasty edges. And in Photoshop CS3, the Magic Wand is grouped with the new Quick Selection tool, which acts like the Magic Wand but works more like a brush that paints a mask.

The important thing to remember about these selection tools (and, in fact, every selection technique in Photoshop) is that you can freely switch among them as you work. Don’t get too hung up on getting one tool to work just the way you want it to; you can always modify the selection using a different technique (this idea of modifying selections is very important, and we’ll touch on it throughout the chapter). Here are some pointers that can help you use the selection tools most efficiently:

You can always move your selection. One of the most frequent changes you’ll make to a selection is moving it without moving its contents. For instance, you might make a rectangular selection, then realize it’s not positioned correctly. Don’t redraw it! Just click and drag the selection using one of the Marquee or Lasso tools. The selection moves, but the pixels underneath it don’t. Or press the arrow keys to move the selection by one pixel. Add the Shift key to move the selection ten pixels for each press of an arrow key.

You can move a selection while you’re drawing it. One of the coolest and least-known selection features is the ability to move a marquee selection (either rectangular or oval) while you’re still dragging out the selection. The trick: hold down the spacebar while you’re still holding down the mouse button. This also works when dragging frames and lines in Adobe InDesign and Adobe Illustrator.

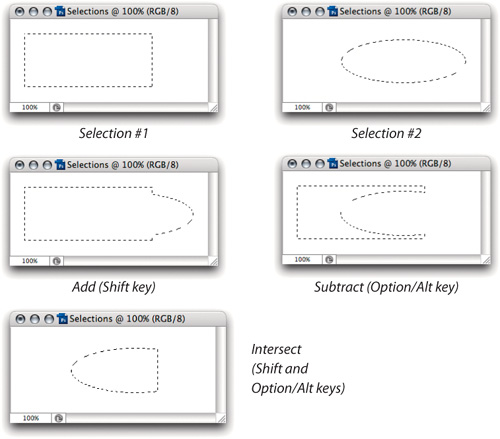

You can add to and subtract from selections. No matter which selection tool you’re using, you can always add to the current selection by holding down the Shift key while selecting. Conversely, you can subtract from the current selection by holding down the Option key (Mac) or Alt key (Windows). Or, if you want the intersection of two selections, hold down the Option/Alt and the Shift keys while selecting (see Figure 9-2). If you don’t feel like remembering these keyboard modifiers, you can click on the Add, Subtract, and Intersect buttons on the far-left side of the Options bar instead.

You can select it again. It’s too easy and natural to charge ahead with edits after selecting an area and later realize you need that last selection back. Fortunately, you can recall it by pressing Command-Shift-D (Mac) or Ctrl-Shift-D (Windows), the shortcut for Select > Reselect).

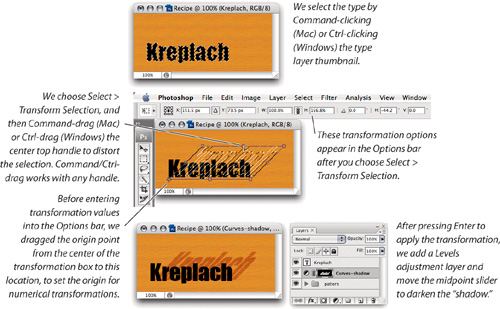

You can transform selections. When you choose Select > Transform Selection, Photoshop places the Free Transform handles around your selection and lets you rotate, resize, skew, move, or distort the selection however you please. When you’re done, press Enter or click the check mark button in the Options bar.

Even less obvious is that after you choose Transform Selection, you can pick options from the Edit > Transform submenu, or type transform values into the fields in the Options bar. For example, if you want to mirror your selection, turn on Transform Selection, drag the center point of the transformation rectangle to the place around which you want the selection to flip, then choose Flip Vertical or Flip Horizontal from the Transform submenu (see Figure 9-3).

The Marquee tool is the most basic of all the selection tools. It lets you draw a rectangular or oval selection by clicking and dragging. If you hold down the Shift key, the marquee is constrained to a square or a circle, depending on whether you have chosen Rectangle or Ellipse in the Marquee Options bar. (Note that if you’ve already made a selection, the Shift key adds to the selection instead.) If you hold down the Option key (Mac) or Alt key (Windows), the selection is centered on where you clicked.

Tip

You can cycle through the Rectangular, Elliptical, Single Row, and Single Column selection tools by choosing from the Tools palette, but it’s faster to press M once to select the tool, then press Shift-M to cycle through the tools. Option/Alt-clicking the Marquee tool in the Tool palette also cycles through them.

Pulling out a single line. If you’ve ever tried to select a single row of pixels in an image by dragging the marquee, you know that it can drive you batty faster than Mrs. Gulch’s chalk-scraping. The Single Row and Single Column selection tools (click and hold the mouse button down on the Marquee tool to get them) are designed for just this purpose. We use them to clean up screen captures or to delete thin borders around an image. They’re also useful with video captures, because each pixel row often equals a video scan line.

Selecting thicker columns and rows. If you want a column or row that’s more than one pixel wide or tall, set the selection style to Fixed Size on the Options bar and type the thickness of the selection into the Height or Width field (note that you have to type a measurement value, like “px” for pixels, or “cm” for centimeters). In the other field, type some number that’s obviously larger than the image, like 10,000px. When you click on the image, the row or column is selected at the thickness you want.

Selecting that two-by-three. You’ve laid out a page with a hole for a photo that’s 2 by 3 inches. Now you want to make a 2-by-3-inch selection in Photoshop. No problem: Choose Constrained Aspect Ratio from the Style pop-up menu in the Options bar (when you have the Marquee tool selected). Photoshop lets you type in that 2-by-3 ratio.

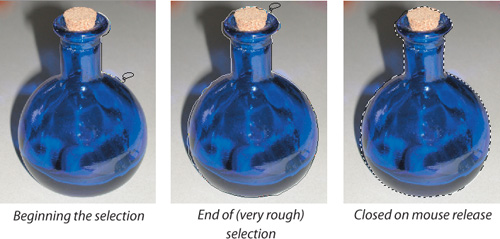

The Lasso tool lets you create a free-form outline of a selection. Wherever you drag the mouse, the selection follows until you finally let go of the mouse button and the selection is automatically closed for you (there’s no such thing as an open-ended selection in Photoshop; see Figure 9-4).

Let go of the Lasso. Two of the most annoying attributes of selecting with the Lasso are that you can’t lift the mouse button while drawing, and you can’t draw straight lines easily (unless you’ve got hands as steady as a brain surgeon’s). The Option key (Mac) or Alt key (Windows) overcomes both these problems.

When you hold down the Option/Alt key, you can release the mouse button, and the Lasso tool won’t automatically close the selection. Instead, as long as the Option/Alt key is held down, Photoshop lets you draw a straight line to wherever you want to go. This solves both problems in a single stroke (as it were).

The folks at Adobe saw that people were using this trick all the time and decided to make it easier on them. Photoshop includes a straight-line Lasso tool that works just the opposite of the normal Lasso tool—when you hold down the Option/Alt key, you can draw nonstraight lines. If you press the L key once, Photoshop gives you the Lasso tool; then press Shift-L, and you get the Straight-line Lasso tool. (Of course, the Shift-key trick won’t work if you’ve turned off the Use Shift Key for Tool Switch option in the Preferences dialog.)

In order to close a selection when you’re using the Straight-line Lasso tool, you have to either click at the beginning of the selection or double-click anywhere.

Select outside the canvas. You may or may not remember at this point in the book that Photoshop saves image data on a layer, even when it extends past the edge of the canvas (out into that gray area that surrounds your picture). Just because it’s hidden doesn’t mean you can’t select it. If you zoom back far enough and enlarge your window enough (or switch to Full Screen mode) so you can see the gray area around the image canvas, you can hold down the Option/Alt key while using the Lasso tool to select into the gray area. (Ordinarily, without the modifier key, the selections stop at the edge of the image.)

Magnetic Lasso. The Magnetic Lasso tool (it, too, is hiding in the Tool palette behind the Lasso tool) lets you draw out selections faster than the regular Lasso tool. The Magnetic Lasso can seem like magic or it can seem like a complete waste of time—it all depends on three things: the image, your technique, and your attitude.

To use the Magnetic Lasso tool, click once along the edge of the object you’re trying to select, then drag the mouse along the edge of the selection (you don’t have to—and shouldn’t—hold down the mouse button while moving the mouse). As you move the mouse, Photoshop “snaps” the selection to the object’s edge. When you’re done, click on the first point in the selection again (or triple-click to close the path with a final straight line).

So the first rule is: Only use this tool when you’re selecting something in your image that has a distinct edge. In fact, the more distinct the better, because the program is really following the contrast between pixels. The lower the contrast, the more the tool gets confused and loses the path.

Here are a few more guidelines that will help your technique:

Be picky with your paths. If you don’t like how the selection path looks, you can always move the mouse backward over the path to erase part of it. If Photoshop has already dropped an anchor point along the path (it does this every now and again), you can remove the last point by pressing the Delete key. Then just start moving the mouse again to start the new selection path.

Tip

While the selection marquee animation helps the human eye see a selection on a possibly busy background, it can also be so distracting that you can’t see how your edits affect the image. To hide those little ants, press Command-H (Mac) or Ctrl-H (Windows), a shortcut for turning off Select > Extras. The only problem is that you must remember that a selection is active, and where the selection is.

Click to drop your own anchor points. For instance, the Magnetic Lasso tool has trouble following sharp corners; they usually get rounded off. If you click at the vertex of the corner, the path is forced to pass through that point.

Vary the Lasso Width as you go. The Lasso Width (in the Options bar) determines how close to an edge the Magnetic Lasso tool must be to select it. In some respects it determines how sloppy you can be while dragging the tool, but it becomes very important when selecting within tight spots, like the middle of a “V”. In general, you should use a large width for smooth areas and a small width for more detailed areas.

Fortunately, you can increase or decrease this setting while you move the mouse by pressing the square bracket keys on your keyboard. (For extra credit, set Other Cursors to Precise in the General Preferences dialog; that way, you can see the size of the Lasso Width.) Also, Shift-[ and Shift-] set the Lasso Width to the lowest or highest value (1 or 40). If you use a pressure-sensitive tablet, turn on the Stylus Pressure check box on the Options bar; the pressure then relates directly to Lasso Width.

Sometimes you want a straight line. You can get a straight line with the Magnetic Lasso tool by Option-clicking (Mac) or Alt-clicking (Windows) once to set the beginning of the segment, and then Option/Alt clicking again to set the end of the segment.

Occasionally, customize your Frequency and Edge Contrast settings. These settings (on the Options bar) control how often Photoshop drops an anchor point and how much contrast between pixels it’s looking for along the edge. In theory, a more detailed edge requires more anchor points (a higher frequency setting), and selecting an object in a low-contrast image requires a lower contrast threshold. To be honest, we’re much more likely to switch to a different selection tool or technique before messing with these settings.

Scrolling while selecting. It’s natural to zoom in close when you’re dragging the Magnetic Lasso tool around. Nothing wrong with that. But unless you have an obscenely large monitor, you won’t be able to see the whole of the object you’re selecting. No problem; the grabber hand works just fine while you’re selecting—just hold down the Spacebar and drag the image around. You can also press the + and - (plus and minus) keys to zoom in and out while you make the selection.

The last rule is patience. Nobody ever gets a perfect selection with the Magnetic Lasso tool. It’s not designed to make perfect selections; it’s designed to make a reasonably good approximation that you can edit. We cover editing selections in “Quick Masks,” later in this chapter.

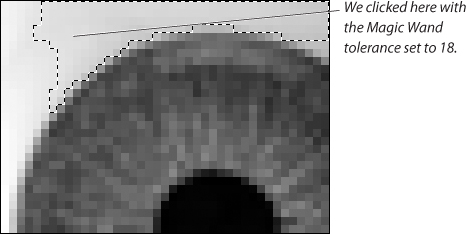

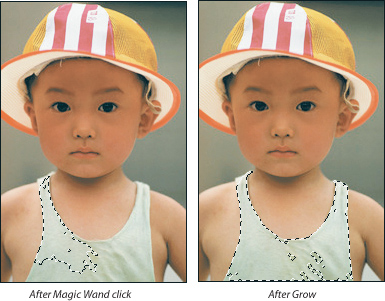

The last selection tool in the Tool palette is the Magic Wand, so called more for its icon than for its prestidigitation. When you click on an image with the Magic Wand (dragging has no effect), Photoshop selects every neighboring pixel with the same or similar gray level or color. “Neighboring” means that the pixels must be touching on at least one side (see Figure 9-5). If you want to select all the similar-toned pixels in the image, whether they’re touching or not, turn off the Contiguous check box in the Options bar before clicking.

How similar can the pixels be before Photoshop pulls them into the selection? It’s entirely up to you. You can set the Tolerance setting on the Options bar from 0 to 255. In a grayscale image, this tolerance value refers to the number of gray levels from the sample point’s gray level. If you click on a pixel with a gray level of 120 and your Tolerance is set to 10, you get any and all neighboring pixels that have values between 110 and 130.

In RGB and CMYK images, however, the Magic Wand’s tolerance value is slightly more complex. The tolerance refers to each and every channel value, instead of just the gray level.

For instance, let’s say your Tolerance is set to 10 and you click on a pixel with a value of 60R 100G 200B. Photoshop selects all neighbors that have red values from 50 to 70, green values from 90 to 110, and blue values from 190 to 210. All three conditions must be met, or the pixel isn’t included in the selection (see “Grow,” later in the chapter for more info).

The Magic Wand will probably be less frequently used now that Photoshop has the Quick Selection tool (which we talk about in the next section). This is no doubt because the Magic Wand involves a lot of careful trial-and-error clicking, which may be why some have dubbed this tool the “Tragic Wand.” The following techniques can increase your chances of success.

Select on a channel, not composite. Because it’s often difficult to predict how the Magic Wand tool is going to work in a color image, we typically like to make selections on a single channel of the image. The Magic Wand is more intuitive on this grayscale image, and when you switch back to the composite channel, the selection’s flashing border will still be there. You can switch to the composite channel by clicking on the RGB, CMYK, or Lab thumbnail in the Layers palette, or by pressing Command-~ (tilde) in Mac OS X or Ctrl-~ (tilde) in Windows.

Sample small, sample often. The Magic Wand tool can be frustrating when it doesn’t select everything you want it to. When this happens, novice users often set the tolerance value higher and try again. Instead, try keeping the tolerance low (between 12 and 32) and Shift-click to add more parts, or Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) to take parts away.

Sample points in the Magic Wand. Note that when you select a pixel with the Magic Wand, you may not get the pixel value you expect. It all depends on the Sample Size pop-up menu on the Options bar (when you have the Eyedropper tool selected). If you select 3 by 3 Average or 5 by 5 Average in that pop-up menu, Photoshop averages the pixels around the one you click on with the Magic Wand. On the other hand, if you select Point Sample, Photoshop uses exactly the one you click. For more hints on sample points, see the sidebar “Reading Color with the Info Palette” in Chapter 7, “Image Adjustment Fundamentals.”

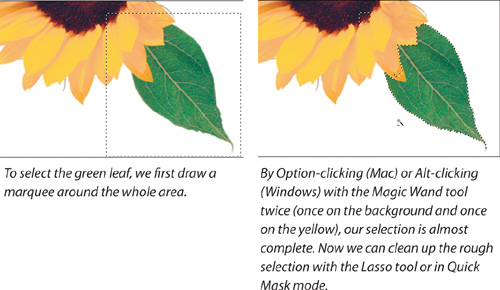

Reverse-selecting. One simple but non-obvious method that we often use to select an area is to select a larger area with the Lasso or Marquee tool and then Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) with the Magic Wand tool on the area we don’t want selected (see Figure 9-6).

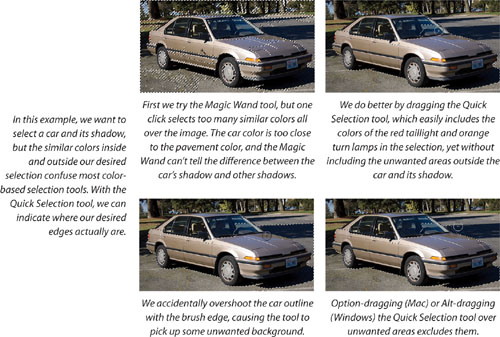

The Quick Selection tool is new in Photoshop CS3. If you’re more comfortable painting a selection area rather than drawing an outline around a selection area, you may want to try this tool. You drag the Quick Selection tool as if you were painting a mask, but instead of getting painted bits back, you get a selection outline as if you had drawn a lasso selection. In that way, the Quick Selection tool lets you paint a selection (as if you were working with masks or channels) but see a marquee outline (as if you were dragging a Lasso or Marquee tool). Another way to look at this tool is that it lets you select while painting, while saving you the step of converting a mask or channel into a selection.

Use the Quick Selection tool as if you’re painting a mask. Drag it through the area you want to select (see Figure 9-7). Like a brush (and unlike the other selection tools), any additional areas you drag with the Quick Selection tool are automatically added to the existing selection—no need to hold Shift to do that. For this reason alone, Magic Wand fans may want give the Quick Selection tool a try. Be careful, though, because if you drag any part of the brush over a color you don’t intend to select, whole unwanted areas may be added to the selection. If this happens, simply press Command-Z (Mac) or Ctrl-Z (Windows) to undo, and try again. To remove an area selectively, Option-drag (Mac) or Alt-drag (Windows) the tool. The tool remembers which colors you’ve included and excluded until you switch tools or switch to Quick Mask mode.

Tip

When using the Quick Selection tool, keep your left hand camped out by the bottom left corner of the keyboard. When it’s there, you’re always ready to press Command-Z/Ctrl-Z to undo, or Option/Alt to remove areas from the selection.

If you’re consistently selecting too much, go to the Options bar and make the brush harder and its size smaller. If you’re using a pressure-sensitive stylus, apply less pressure for a smaller brush tip, or just turn off Pen Pressure in the Brush pop-up menu and use a small brush size.

In the Options bar, the Auto-Enhance option tries to guess at making a better selection. If you think it’s guessing wrong, turn off Auto-Enhance and fine-tune the edge yourself by clicking Refine Edge. We cover the Refine Edge dialog later in this chapter.

Tip

If the background contains colors that don’t also occur in the subject, Option-drag (Mac) or Alt-drag (Windows) through unwanted background colors. This marks those colors “off limits,” so that the tool avoids those colors when you finally drag the tool through the areas you do want to select.

While the Quick Selection tool has gotten a lot of press as a miraculous selection tool, it’s really just another weapon in your selection arsenal. Like the Magnetic Lasso, the effectiveness of the Quick Selection tool depends a large part on the amount of contrast along the edges of the area you want to isolate. There are still many situations where another selection method (such as Select > Color Range) may be faster or easier.

We need to take a quick diversion off the road of making selections and into the world of what happens when you move a selection. Photoshop has traditionally had a feature called floating selections. A floating selection is a temporary layer just above the currently selected layer; as soon as you deselect the floating selection, it “drops down” into the layer, replacing whatever pixels were below it. When you move a selection of pixels within an image, Photoshop acts as though those pixels were on a layer. Unfortunately, while these floating selections act like layers, they don’t show up in the Layers palette. For that reason, The Photoshop engineering team has been trying to get rid of floating selections for years, but there are still a few instances where they appear. We prefer to avoid floating selections and instead move pixels to a real layer for accurate positioning.

You can manipulate a floating selection as you do a layer. You can change the mode of a floating selection to Multiply, Screen, Overlay, or any of the others, and even change its opacity. But if the floating selection doesn’t appear in the Layers palette, how are you to make these changes? After floating the pixels, choose Edit > Fade. (Nonintuitive, but true.) However, as soon as you try to paint on it, or run a filter, or do almost anything else interesting to the floating selection, Photoshop deselects it and drops it back down to the layer below it. That’s one reason we would rather just place pixels onto a real layer before messing with them.

Tip

To cut out selected pixels and leave a blank spot behind, drag the selection with the Move tool. If you’d rather copy the pixels into a floating selection, you can hold down the Option/Alt key while dragging or press Command/Ctrl-J. Note that floating selections doesn’t appear on the Layers palette.

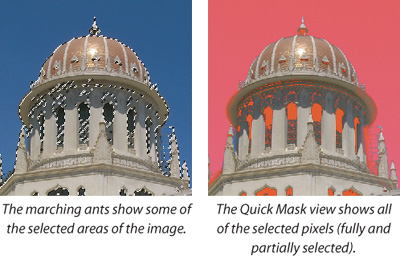

When you select a portion of your image, you see the flashing dotted lines—they’re fondly known as marching ants to most Photoshop folks. But what are these ants really showing you? In a typical selection, the marching ants outline the boundary of pixels that are selected 50 percent or more. There are often loads of other pixels that are selected 49 percent or less that you can’t see at all from the marching ants display. Very frustrating.

Fortunately, Photoshop includes a Quick Mask mode to show you exactly what’s selected and how much each pixel is selected. When you enter Quick Mask mode (select the Quick Mask icon in the Tool palette or type Q), you see the underlying selection channel in all its glory. However, because the Quick Mask is overlaying the image, the black areas of the mask are 50 percent opaque red and the white (selected) areas are even more transparent than that (see Figure 9-8). The red is supposed to remind you of Rubylith, if you remember the amber-colored acetate we used to cut up to create masks for film.

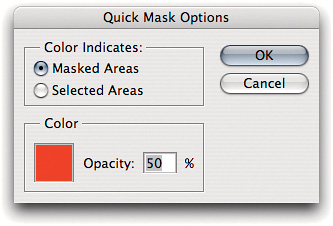

You can change both the color and the transparency of the Quick Mask in the Quick Mask Options dialog (see Figure 9-9)—the fast way to get there is to double-click on the Quick Mask icon in the Tool palette. If the image you’re working on has a lot of red in it, you’ll probably want to change the Quick Mask color to green or some other contrasting color. Either way, we almost always increase the opacity of the color to about 75 percent so it displays more prominently against the background image.

Note that these changes aren’t document-specific. That is, they stick around in Photoshop until you change them.

The powerful thing about Quick Masks isn’t just that you can see a selection you’ve made, but rather that you can edit that selection with precision. When you’re working in Quick Mask mode, you can paint using any of the painting or editing tools in Photoshop, though you’re limited to painting in grayscale. Painting with black is like adding digital masking tape (it subtracts from your selection), and painting with white (which appears transparent in this mode) adds to the selection.

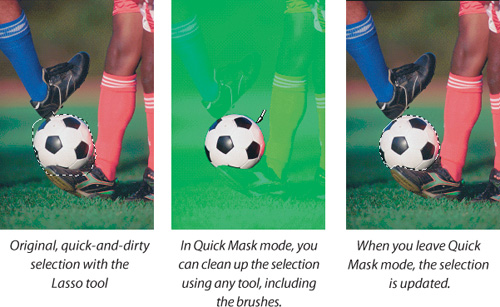

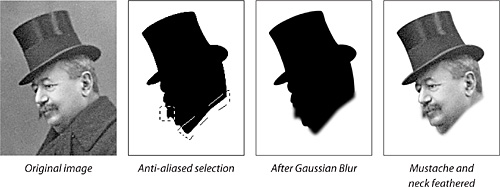

If the element in your image is any more complicated than a rectangle, you can use Quick Mask to select it quickly and precisely. (We do this for almost every selection we make.) Here’s how:

Select the area as carefully as you can using any of the selection tools (but don’t spend too much time on it).

Switch to Quick Mask mode (press Q).

Paint or edit using the Brush tool (or any other painting or editing tool) to refine the selection you’ve made. Remember that partially transparent pixels will be partially selected (we often run a Gaussian Blur filter on the Quick Mask to smooth out sharp edges in the selection).

Switch out of Quick Mask mode by pressing Q again. The marching ants update to reflect the changes you’ve made (see Figure 9-10).

Tip

Even when you’re in Quick Mask mode, it’s difficult to see partially selected pixels (especially those that are less than 50 percent selected). Note that the Info palette shows grayscale values when you’re in this mode; those percentage values represent the opacity of the selection at that pixel, which makes partial (feathered) selections possible. It’s just another reason always to keep an eye on the Info palette.

Note that if you switch to Quick Mask mode with nothing selected, the Quick Mask will be empty (transparent). This would imply that the whole document is selected, but it doesn’t work that way.

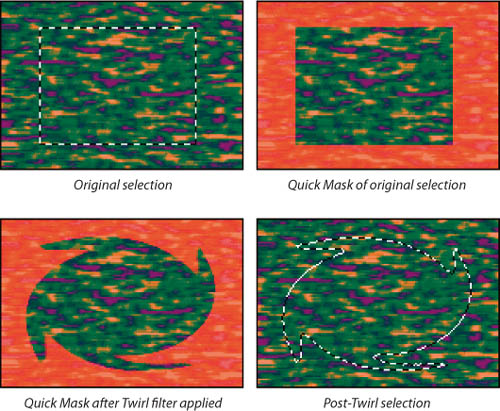

Filtering Quick Masks. The Quick Mask mode is also a great place to apply filters or special effects. Any filter you run affects only the selection, not the entire image (see Figure 9-11). For instance, you could make a rectangular selection, switch to Quick Mask mode, and then run the Twirl filter. When you leave Quick Mask mode, you can fill, paint, or adjust the altered selection.

Customizing the color. If you’re the kind of person who likes the selected areas to be black (or red, or whatever other color you choose in Quick Mask Options) and the unselected areas to be fully transparent, you can change this in Quick Mask Options. Even faster, you can Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) on the Quick Mask icon in the Tool palette. Note that when you do this, the icon actually changes to reflect your choice.

If you do change the way that Quick Mask works, you’ll probably want to reverse the way that channels and layer masks work, too (double-click on the channel in the Channels palette). Otherwise, you’ll have a hard time remembering whether black means selected or unselected. You might not need to worry about this too much; when a selection is the opposite of what you want, just press Command-Shift-I (Mac) or Ctrl-Shift-I (Windows), the shortcut for Select > Inverse. When you’re editing a Quick Mask, channel, or layer mask, you can swap black and white by pressing Command-I (Mac) or Ctrl-I (Windows), the shortcut for Image > Adjustments > Invert.

If you’ve ever been in a minor car accident and later talked to an insurance adjuster, you’ve probably been confronted with their idea that you may not be fully blameless or at fault in the accident. And just as you can be 25 percent or 50 percent at fault, you can partially select pixels in Photoshop. One of the most common partial selections is around the edges of a selection. And the two most common ways of partially selecting the edges are anti-aliasing and feathering.

If you use the Marquee tool to select a rectangle, the edges of the selection are nice and crisp, which is probably how you want them. Crisp edges around an oval or irregular shape, however, are rarely a desired effect. That’s because of the stair-stepping required to make a diagonal or curved line out of square pixels. What you really want (usually) is partially selected pixels in the notches between the fully selected pixels. This technique is called anti-aliasing.

Every selection in Photoshop is automatically anti-aliased for you, unless you turn this feature off in the selection tool’s Options bar. Unfortunately, you can’t see the anti-aliased nature of the selection unless you’re in Quick Mask mode, because anti-aliased (partially selected) pixels are often less than 50 percent selected. Note that once you’ve made a selection with Anti-alias turned off on the Options bar, you can’t anti-alias it—though there are ways to fake it (see below).

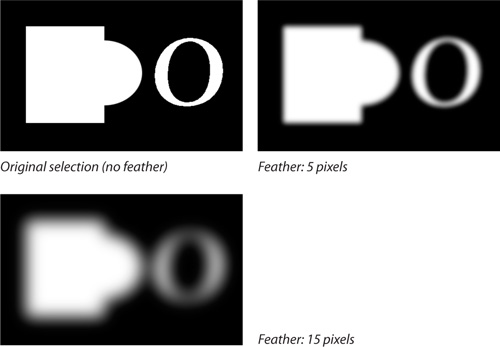

Anti-aliasing simply smooths out the edges of a selection, adjusting the amounts that the edge pixels are selected in order to appear smooth. But it’s often (too often) the case that you need a larger transition area between what is and isn’t selected. That’s where feathering comes in. Feathering is a way to expand the border around the edges of a selection. The border isn’t just extended out; it’s also extended in (see Figure 9-12).

Tip

In Mac OS X, the traditional Photoshop keyboard shortcut for Feather is Command-Option-D. Mac OS X took over this shortcut for hiding and showing the Dock. If you want the Feather shortcut to work, either redefine it by choosing Edit > Keyboard Shortcuts in Photoshop, or open the Keyboard Shortcuts tab in Mac OS X System Preferences to redefine or disable the hide/show Dock shortcut.

To understand what feathering does, it’s important to understand the concept of the selection channel that we talked about earlier in the chapter. That is, when you make a selection, Photoshop is really “seeing” the selection as a grayscale channel behind the scenes. The black areas are totally unselected, the white areas are fully selected, and the gray areas are partially selected.

When you feather a selection, Photoshop is essentially applying a Gaussian Blur to the grayscale selection channel. (We say “essentially” because in some circumstances—like when you set a feather radius of over 120 pixels—you get a slightly different effect; however, there’s usually so little difference that it’s not worth bothering with. For those technoids out there who really care, Adobe tells us that a Gaussian Blur of the Quick Mask channel is a tiny bit more accurate and “true” than a feather.)

There are several ways to feather a selection:

Before selecting, specify a feather amount in the Options bar.

After selecting, click Refine Edge in the Options bar and adjust the Feather option. (We talk about Refine Edge in the next section.)

After selecting, choose Select > Modify > Feather.

Apply a Gaussian Blur to the selection’s Quick Mask.

Tip

You don’t need to use whole numbers when feathering. We find we often need a value of only 0.5 or 0.7 to get the a nice, subtle transition we’re looking for. It’s a great way to anti-alias a hard-edged selection, mask, or channel.

If you use the Refine Edge dialog, your entire selection is feathered. Sometimes, however, you want to feather only a portion of the selection. Maybe you want a hard edge on one half of the selection and a soft edge on the other. You can do this by switching to Quick Mask mode, selecting what you want feathered with any of the selection tools, and applying a Gaussian Blur to it. When you flip out of Quick Mask mode, the feathering is included in the selection.

Note that if you want a nice, soft feather between what is feathered and what isn’t, you first have to feather the selection you make while you’re in Quick Mask mode (see Figure 9-13).

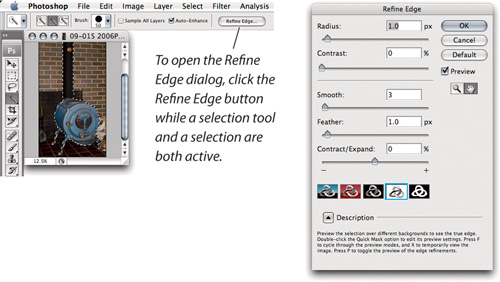

Software engineering teams sometimes make new features simply by streamlining multistep production chores. The Refine Edge dialog, new in Photoshop CS3, represents this type of new feature. In previous versions of Photoshop, if you applied the Select > Feather command, the only way to actually see the size of the feather was to view the selection as a quick mask or channel. And we have often mentioned how you can tweak a selection edge by converting the selection to a quick mask or a channel, and then using image-editing commands (such as Levels and Gaussian Blur) to alter contrast along the edges of the selection channel. Of course, that meant you had to know which series of operations would get you to the result you wanted.

The Refine Edge dialog takes away much of that brainwork. Now you can simply tell Refine Edge how you want to tune the selection edge, and it’s done. Behind the scenes, Refine Edge works with a selection as a channel, so that you don’t have to go through those steps yourself. You can even use Refine Edge on a mask or channel.

Tip

Refine Edge isn’t just an Options bar button. It’s also a command (Select > Refine Edge), so you can also open it by pressing its keyboard shortcut—Command-Option-R (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-R (Windows).

To use Refine Edge, click the Refine Edge button in the Options bar while a selection tool and a selection are both active (see Figure 9-14). You’ll see five sliders divided by a line. The Radius and Contrast options above the line set the initial edge, and the other three options below the line take it from there. The best way to use the controls is as they’re laid out, in order from top to bottom.

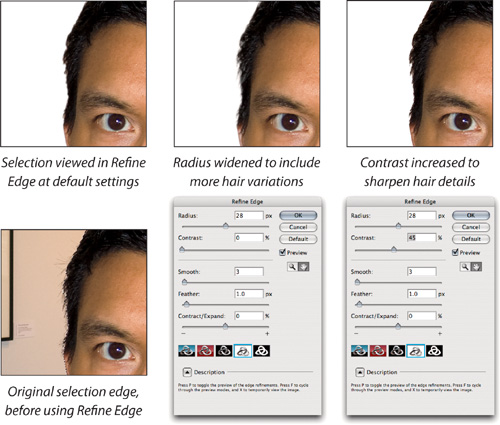

Radius. Starting from the initial edge you created, the Radius value determines how far out Refine Edge extends the feathered transition between selected and unselected pixels. A higher Radius value can help when the exact edge is harder to identify, such as the edge of a soft shadow or hair.

Tip

Refine Edge should usually be your next step after using tools such as the Quick Selection or Magnetic Lasso. Those tools usually produce an edge that needs to be cleaned up.

Radius is more sophisticated than a standard feather or edge blur, in that it protects existing hues and creates a less artificial-looking transition. For a traditional feather, leave Radius at 0 and use the Feather slider instead (see Figure 9-15).

Contrast. This option determines the sharpness of the feathered transition across the radius you set. A higher value creates a sharper edge.

Smooth. The Smooth slider evens out bumps along the selection edge to help compensate for sloppy selections. However, if your edge follows details like hair, a high Smooth value can obliterate the details. If you have to set such a high Smooth value that you lose details, you may need to click Cancel and improve the precision of your initial selection (see Figure 9-16).

Feather. The Feather slider is essentially the traditional Feather command in Photoshop (which is still available at Select > Feather). It simply blurs the edge resulting from your Radius, Contrast, and Smooth settings.

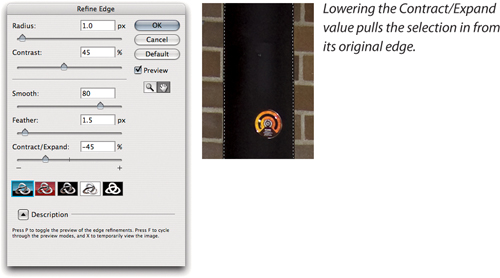

Contract/Expand. If your selection is a little bit inside or outside of the area you wanted to select, use Contract/Expand to compensate. As the last option in the second group of options, it acts on the results of the four options above it, so if no Contract/Expand value gets you what you want, try adjusting the other sliders (see Figure 9-17).

Tip

To toggle the Refine Edge selection view off and on, press the X key. Of course, as in other dialogs, the P key toggles the Preview check box.

Selection View icons. The five icons along the bottom of the Refine Edge dialog are simply different ways of previewing the selection. They follow the basic principle we set forth earlier in the chapter: A selection can be represented as a marching-ants border, a Quick Mask, or a grayscale image channel. Click an icon to set the view your way, or just press F to toggle through the viewing modes with the keyboard.

It isn’t just for selections. Instead of using Levels and Curves to adjust layer mask edges, the Quick Mask view, and channels, the next time you need to do that, try Refine Edge instead. It’s completely functional when a layer mask or channel is selected; it isn’t necessary for the layer mask or channel to be visible. Sounds incidental, but this is actually a huge, huge feature—it means you can use Refine Edge to edit a layer mask while seeing its true effect on the final image.

Back in “Masking-Tape Selections,” we told you that selections, masks, and channels are all the same thing down deep: grayscale images. This is not intuitive, nor is it easy to grasp at first. But once you really understand this point, you’ve taken the first step toward really surfing the Photoshop big waves.

A channel is a solitary grayscale image—each pixel described using either 8 bits or 16 bits of data, depending on whether or not it’s a high-bit image. You can have up to 56 channels in a document—and that includes the three in an RGB image or four in a CMYK image. (Actually, there are two exceptions: First, images in Bitmap mode can only contain a single 1-bit channel; second, Photoshop allows one additional channel per layer to accommodate layer masks, which we’ll talk about later in this chapter.)

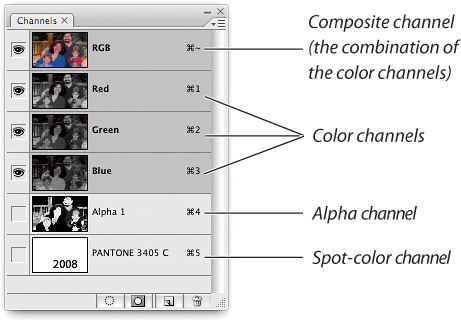

But in the eyes of the program, not all channels are created equal. There are three types of channels: alpha, color, and spot-color channels (see Figure 9-18). We discuss the first two here, and the third in bonus Chapter 13, “Spot Colors and Duotones.” For the URL to download this chapter, see “Introduction: Photoshop in the Real World.”

People get very nervous when they hear the term “alpha channel,” because they figure that with such an exotic name, it has to be a complex feature. Not so. An alpha channel is simply a grayscale picture. Alpha channels let you save selections, but a solid understanding of these beasts is also crucial to tackling layer masks.

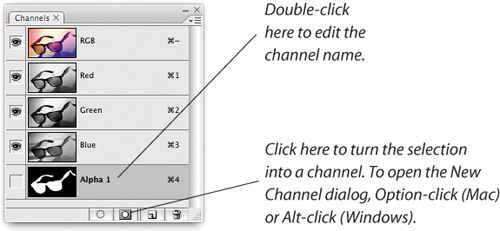

Saving selections. Again, selections and channels are really the same thing down deep (even though they have different outward appearances), so you can turn one into the other very quickly. Earlier in this chapter we discussed how you can see and edit a selection by switching to Quick Mask mode. But Quick Masks are ephemeral things, and aren’t much use if you want to hold onto that selection and use it later.

When you turn a selection into an alpha channel, you’re saving that selection in the document. Then you can go back later and edit the channel or turn it back into a selection.

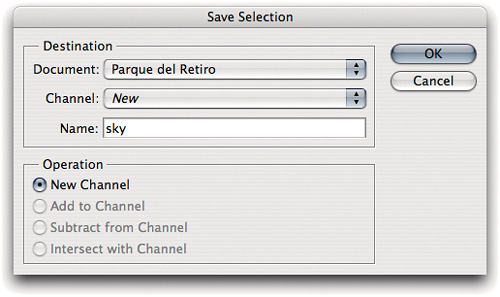

As we pointed out in the last chapter, the slow way to save a selection is to choose Select > Save Selection. It’s a nice place for beginners because Photoshop provides you with a dialog (see Figure 9-19). But pros don’t bother with menu selections when they can avoid them. Instead, click the Save Selection icon in the Channels palette. Or, if you want to see the Channel Options dialog first (for instance, if you want to name the channel), Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) the icon (see Figure 9-20). Of course, you can also assign a keyboard shortcut to the New Channel feature if you use it a lot.

Loading selections. Saving a selection as an alpha channel doesn’t do you much good unless you can retrieve it. Again, the slowest method is to choose Select > Load Selection (though there are benefits to this method; see “Saving Channels in Other Documents,” later in this chapter).

Tip

Every time it takes you more than 10 seconds to make a selection in your image, you should be thinking, “Save this selection.” We try to save every complex selection as a channel or a path until the end of the project (and sometimes we even archive them, just in case). You never know when you’ll need them again, and they don’t take up that much space.

One step better is to Command-click (Mac) or Ctrl-click (Windows) on the channel that you want to turn into a selection. Even better, press the Command and Option (Mac) or Ctrl and Alt (Windows) keys along with the number key of the channel you want. For instance, if you want to load channel six as a selection on a Mac, press Command-Option-6. Note that if you press Command-Option-~ (tilde) (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-~ (Windows), you load the luminosity mask. This isn’t really the “lightness” of the image; rather, it’s like getting a grayscale version of your image.

Channels in TIFF files. If you’re saving a mess of channels along with the image you’re working on, and you want to save the file as a TIFF, you should probably turn on LZW compression in the Save as TIFF dialog. Zip compression is even better, though QuarkXPress and most other programs can’t read Zip-compressed TIFF files yet. However, Adobe InDesign can, and of course you can always reopen Zip-compressed TIFF files in Adobe Photoshop. Whatever the case, use some kind of compression—otherwise, the TIFF will be enormous. Of course, you could save in the native Photoshop format, but we find that a Zip-compressed TIFF file is almost always smaller on disk (see Chapter 12, “Image Storage and Output”).

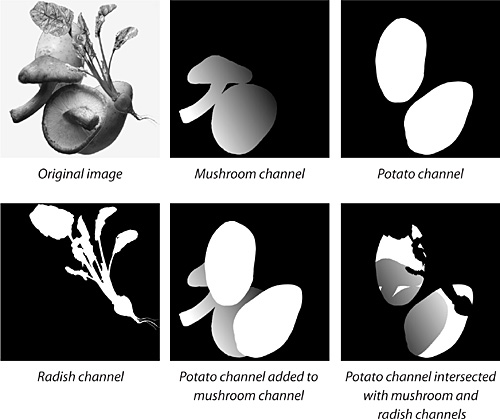

Adding, subtracting, and intersecting Selections. Let’s say you have an image with three elements in it. You’ve spent an hour carefully selecting each of the elements, and you’ve saved each one in its own channel (see Figure 9-21). Now you want to select all three objects at the same time.

In the good old days, you would have sat around trying to figure out the appropriate channel operations (using Calculations) to get exactly what you wanted. But it’s a kinder, gentler Photoshop now. After you load one channel as a selection, you can choose Select > Load Selection to add another channel to the current selection, subtract another channel, or find the intersection between the two selections.

Even easier, use the key-click combinations in Table 9-1. Confused? Don’t forget to watch the cursor icons; as you hold down the various key combinations, Photoshop indicates what will happen when you click.

Table 9-1. Working with selections

To get this. . . | . . .press this: |

|---|---|

Add channel to current selection | Command-Shift-click (Mac) Ctrl-Shift-click (Windows) |

Subtract channel from selection | Command-Option-click (Mac) Ctrl-Alt-click (Windows) |

Intersect current selection and channel | Command-Shift-Option-click (Mac) Ctrl-Shift-Alt-click (Windows) |

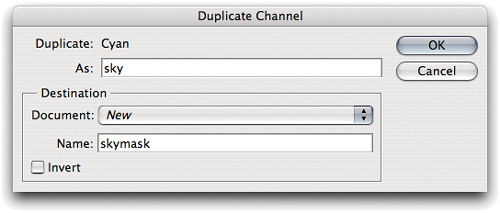

As we said earlier, your alpha channels don’t all have to be in the same document. In fact, if you’ve got more than 56 channels, you have to have them in multiple documents. But even if you have fewer than 56, you may want to save off channels in order to reduce the current file’s size. Here are a bunch of tips we’ve found helpful in moving channels back and forth between documents.

Saving channels in other documents. As long as another file is currently open, you can save a selection into it using Save Selection, or you can load a selection (from a channel) from the file using the menu items. You can even save selections into a new document by selecting New from the Document pop-up menu in the Save Selection dialog.

If you have two similar documents open and you’ve carefully made and saved a selection in one image, you might want to use it in another image. Instead of copying and pasting the selection channel, take a shortcut and use the Load Selection dialog. You can load the selection channel directly by choosing it from the Document and Channel pop-up menus.

Tip

The fastest way to copy a channel between documents is to drag the channel’s thumbnail from the Channels palette to the other document. It’s less of a drag on the system than copying and pasting. Again, for the channel to align with the new document, the two documents must be the same size.

The catch here is that both documents have to have exactly the same pixel dimensions (otherwise, Photoshop wouldn’t know how to place the selection properly).

If you’ve already saved your selection into a channel in document A, how can you then get that channel into document B? One method is to select the channel and choose Duplicate Channel from the Channel palette menu (see Figure 9-22). Here you can choose to duplicate the channel into a new document or any other open document (as long as the documents have the same pixel dimensions).

Dragging selections. Photoshop is full of little, subtle features that make life so much nicer. For instance, you can drag any selection from one document into another document using one of the selection tools. (The Move tool actually moves the pixels inside the selection; the selection tools move the selection itself.)

Normally, the selection “drops” wherever you releaese the mouse button. However, if the two documents have the same pixel dimensions, you can hold down the Shift key to pin-register the selection (meaning it lands in the same location as it was in the first document). If the images don’t have the same pixel dimensions, the Shift key centers the selection.

When a color image is in RGB mode (under the Mode menu), the image is made up of three channels: red, green, and blue. Each of these channels is exactly the same as an alpha channel, except that they’re designated as color channels. You can edit each color channel separately from the others. You can independently make a single color channel visible or invisible. But you can’t delete or add a color channel without first changing the image mode.

The first thumbnail in the Channels palette (above the color channels) is the composite channel. Actually, this isn’t really a channel at all. Rather, the composite channel is the full-color representation of all the individual color channels mixed together. It gives you a convenient way to select or deselect all the color channels at once, and also lets you view the composite color image, even while you’re editing a single channel.

Selecting and seeing channels. The tricky thing about working with channels is figuring out which channel(s) you’re editing and which channel(s) you’re seeing on the screen. They’re not always the same!

The Channels palette has two columns. The left column contains little eyeball icons that you can turn on and off to show or hide individual channels. Clicking on one of the thumbnails in the right column not only displays that channel, but lets you edit it, too. The channels that are selected for editing are highlighted. The two columns are independent of each other because editing and seeing the channels are not the same thing.

Channel shortcuts. When you’re jumping from one channel to another, skip the clicking altogether and press the Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) key along with the number of the channel you want. For instance, in Mac OS X, Command-1 shows the red channel (or whatever the first channel is), and Command-4 shows the fourth channel (the first alpha channel in an RGB image or the black channel in a CMYK image). Sorry, there’s no way (that we know of) to select channels above number nine with keystrokes. To select the color composite channel (deselecting all other channels in the process), press Command-~ (tilde) (Mac) or Ctrl-~ (Windows).

You can see as many channels at once as you want by clicking in the channel’s eyeball check boxes. To edit more than one channel at a time, Shift-click on the channel thumbnail.

Note that when you display more than one channel at a time, the alpha channels automatically switch from their standard black and white to their channel color (you can specify what color each channel uses in Channel Options—double-click on the channel thumbnail).

If making selections using lassos and marquees and then saving or loading them were all it took to make selections in Photoshop, life would be simpler, but duller. Fortunately for us, there are many more things you can do with selections, and they all—well, almost all—help immeasurably in the production process.

You can find each additional selection feature under the Select menu: Grow, Similar, Color Range, and Modify. Let’s explore each of these and how they can speed up your work.

Earlier in the chapter, when we were talking about the Magic Wand tool, we discussed the concept of tolerance. This value tells Photoshop how much brighter or darker a pixel (or each color channel that defines a pixel) can be and still be included in the selection.

Let’s say you’re trying to select an apple using the Magic Wand tool with a tolerance of 24. After clicking once, perhaps only half of the apple is selected; the other half is slightly shaded and falls outside the tolerance range. You could deselect, change the tolerance, and click again. However, it’s much faster to choose Select > Grow.

When you choose the Grow command, Photoshop selects additional pixels according to the following criteria:

First, it finds the highest and lowest gray values of every channel of every pixel selected—the highest red, green, and blue, and the lowest red, green, and blue of the bunch of already-selected pixels (or the highest cyan, magenta, yellow, and black, and so on).

Next, it adds the tolerance value to the highest values and subtracts it from the lowest values in each channel. Therefore, the highest values get a little higher and the lowest values get a little lower (of course, it never goes above 255 or below 0).

Finally, Photoshop selects every adjacent pixel that falls between all those values (see Figure 9-24).

In other words, Photoshop tries its hardest to spread your selection in every direction, but only in similar colors. However, it doesn’t always work the way you’d want. In fact, sometimes it works very oddly indeed.

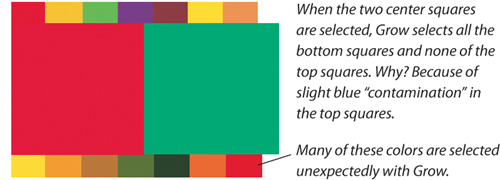

For instance, if you select a pure red area (made of 255 red and no blue or green), and a pure green area (made of 255 green and no red or blue), then select Grow, Photoshop selects every adjacent pixel that has any red or green in it as long as the blue channel is not out of tolerance’s range. That means that it’ll pick out dark browns, lime greens, oranges, and so on—even if you set a really small tolerance level (see Figure 9-25).

If you switch to a color channel (like red or cyan) before selecting Grow, Photoshop grows the selection based on that channel only. This can be helpful because it’s much easier to predict how the Magic Wand and Grow features will work on one channel.

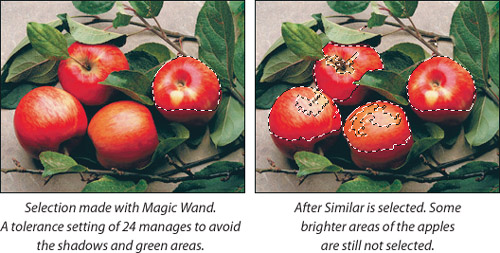

The Grow command only selects contiguous areas of your image. If you’re trying to select the same color throughout an image, you may click and drag and grow yourself into a frenzy before you’re done. Choosing Select > Similar does the same thing as choosing Select > Grow, but it chooses pixels from throughout the entire image (see Figure 9-26).

Note that Similar and Grow are both attached to the settings on the Options bar when you have the Magic Wand selected; Photoshop applies both the Wand’s tolerance and its anti-alias values to these commands. We can’t think of any reason to turn off anti-aliasing, but it’s nice to know you have the option.

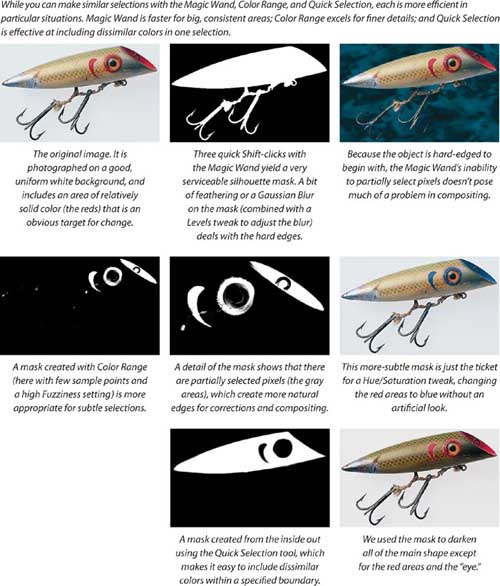

One of the problems with Similar and Grow is that you rarely know what you’re going to end up with. On the other hand, Color Range lets you make color-based selections interactively, and shows you exactly which pixels will be selected. But there’s one other advantage of Color Range over the Magic Wand features (we think of Similar and Grow as extensions of the Magic Wand).

The Magic Wand–based features either select a pixel or they don’t (the exception is anti-aliasing around the edges of selections, which only partially selects pixels there). Color Range, however, fully selects only a few pixels and partially selects a lot of pixels (see Figure 9-27). This can be incredibly helpful when you’re trying to tease a good selection mask out of the contents of an image.

Tip

Color Range is always in Sample Merged mode. It sees your image as though all the visible layers were one. To exclude a layer from the selection mask, hide that layer before opening Color Range.

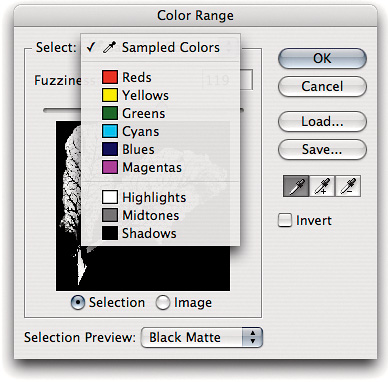

There are four areas you should be aware of in the Color Range dialog: selection eyedroppers, the Fuzziness slider, canned sets of colors, and Selection Preview.

Adding and deleting colors. When you open Color Range, Photoshop creates a selection based on your foreground color. Then you can use the eyedropper tools to add or delete colors in the image (or, better yet, hold down the Shift key to get the Add Color to Mask eyedropper, or the Option/Alt key to get the Remove Color from Mask eyedropper). Note that you can always scroll or magnify an area in the image. You can even select colors from any other open image.

Tip

To open the Color Range dialog with exactly the same settings you last used, hold down the Option key (Mac) or the Alt key (Windows) when choosing Select > Color Range.

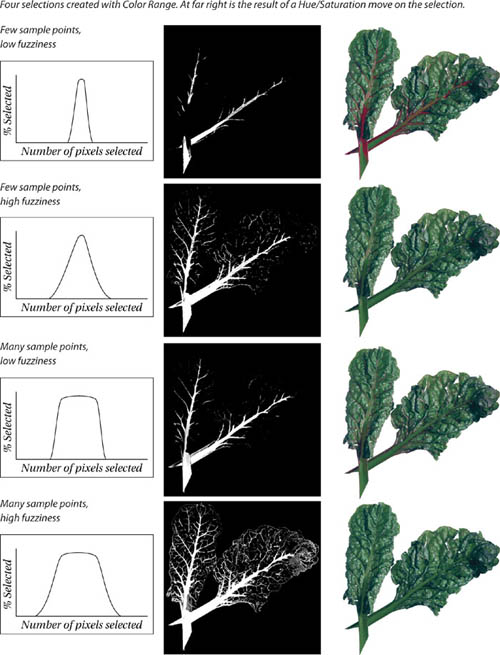

The Fuzziness factor. The Fuzziness slider in the Color Range dialog is not the same as the Tolerance field on the Magic Wand Options bar. As we said earlier, pixels that fall within the tolerance value are either fully selected or not; pixels that fall on the border between the selected and unselected areas may be partially selected, but those are only border pixels. Color Range uses the Fuzziness value to determine not only whether a pixel should be included, but also how selected it should be. We’re not going to get into the hard-core math, but Figure 9-28 should give you a pretty good idea of how fuzziness works.

Sampling vs. Fuzziness. Should you use lots of sample points or a high Fuzziness setting? It depends on the type of image. To select large areas of similar color, tend toward a lower Fuzziness (10 to 15) to avoid selecting stray pixels. For fine detail, you need to use higher Fuzziness settings, because the fine areas are generally more polluted with colors spilling from adjacent pixels. Either way, try adding sample points to increase the selection range before you increase fuzziness.

Instead of creating a selection mask with the eyedroppers, you can let Photoshop select all the reds, or all the blues, or yellows, or any other primary color, by choosing the color in the Select pop-up menu (see Figure 9-29). The greater the difference between the color you choose and the other primaries, the more the pixel is selected. (To get really tweaky for a moment: The percentage the pixel is selected is the percentage difference between the color you choose and the primary color with the next highest value.)

You can also choose from Highlights, Midtones, or Shadows—which we tend to use much more than the preset (what we call “canned”) colors in the Select pop-up menu. When you choose one of these, Photoshop decides whether to select a pixel (or how much to select it) based on its Lab luminance value (see Table 9-2 and Chapter 4, “Color Settings,” for more information on Lab mode).

We find selecting Highlights, Midtones, and Shadows most useful when selecting a subset of a color we’ve already selected (see the tip near the top of this page).

Tip

You can change your Quick Mask options settings while the Color Range dialog is open. Hold down the Option key (Mac) or Alt key (Windows) while selecting Quick Mask from the Selection Preview pop-up menu.

Invert the Color Range selection. Do you often find yourself following up a Color Range selection by choosing Select > Invert? If you are trying to select the opposite of what’s selected in the Color Range dialog, you can remove that extra step by turning on the Invert check box in the Color Range dialog; Photoshop automatically inverts the selection for you. If you already have a selection made when you invert the Color Range selection, Photoshop deselects the Color Range pixels from your selection.

Selection Preview. The last area to pay attention to in the Color Range dialog is the Selection Preview pop-up menu. When you select anything other than None (the default) from this menu, Photoshop previews the Color Range selection mask.

The first choice, Grayscale, shows you what the selection mask would look like if you saved it as a separate channel. The second and third choices, Black Matte and White Matte, are the equivalent of copying the selected pixels out and pasting them on a black or white background. This is great for seeing how well you’re capturing edge pixels. The last choice, Quick Mask, is the same thing as clicking OK and immediately switching into Quick Mask mode.

Tip

Instead of using the Image and Selection radio buttons, press the Command or Control key (either one works on the Mac). This toggles between the Selection Preview and Image Preview much faster than you can click buttons.

Because the Selection Preview can slow you down, we recommend turning it on only when you need to, then turning around and switching back to None. It can be really helpful in making sure you’re selecting everything you want, but it can also be a drag on productivity.

When you think of the most important part of your selection, what do you think of? If you answer, “what’s selected,” you’re wrong. No matter what you have selected in your image, the most important part of the selection is the boundary or edge. This is where the tire hits the road, where the money slaps the table, where the invoice smacks the client. No matter what you do with the selection—whether you copy and paste it, paint within it, or whatever—the quality of your edge determines how effective your effect will be.

When making a precise selection, you often need to make subtle adjustments to the boundaries of the selection. The four menu items on the Modify submenu under the Select menu—Border, Smooth, Expand, and Contract—focus entirely on this task.

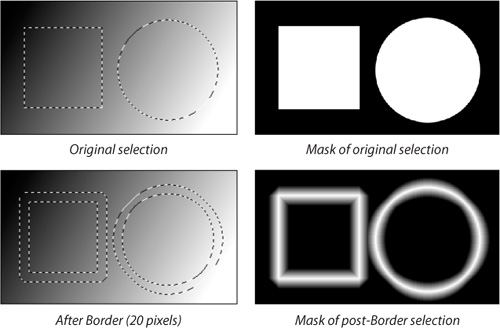

Border. Police officers, take note: There’s a faster way to get a doughnut than driving down to the local Circle K. Draw a circle using the Marquee tool, then choose Select > Modify > Border. You can even specify how thick you want your doughnut (in pixels, of course). Border transforms the single line (the circle) into two lines (see Figure 9-30).

The problem with Border is that it only creates soft-edged borders. If you draw a square and give it a border, you get a soft-edged shape that looks more like an octagon than a square. In many cases, this is exactly what you want and need. But other times it can ruin the mood faster than jackhammers outside the bedroom window. To get a harder edge out of the Border command, switch to Quick Mask mode (press Q), then use the Levels or Curves dialog to adjust the edge of the selection. If the edge of the selection is too jaggy, apply a 0.5-pixel Gaussian Blur to smooth it out. Remember that when you’re in Quick Mask mode, you can select the area to which you want to apply the levels or blur.

Creating More Border Options. Here’s one other way to make a border with a sharper, more distinct edge.

Save your selection as an alpha channel.

While the area is still selected, choose Select > Modify > Expand.

Save this new selection as an alpha channel.

Load the original selection from the alpha channel you saved it in.

Mix the two selections (expanded and contracted) together by Command-Option-clicking (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-clicking (Windows) the other channel.

You can save this selection and delete one or both of the other alpha channels you saved. Note that you don’t have to expand and contract the selection; this method also lets you choose to only contract or expand.

Note that we also discuss another way to make borders (edge masks) in Chapter 10, “Sharpness, Detail, and Noise Reduction.”

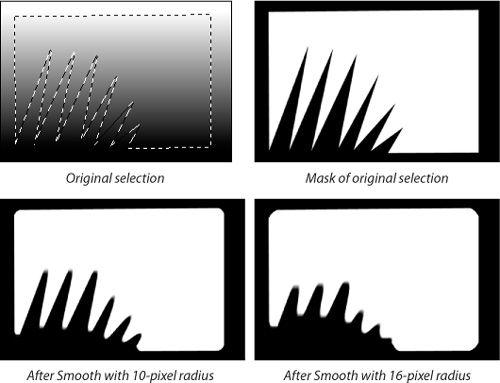

Smooth. The problem with making selections with the Lasso tool is that you often get very jaggy selection lines; the corners are too sharp, the curves are too bumpy. You can smooth these out by choosing Select > Modify > Smooth. Like most selection operations in Photoshop, this actually runs a convolution filter over the selection mask—in this case, the Median filter. That is, selecting Smooth is exactly the same thing as switching to Quick Mask mode and choosing the Median filter.

Smooth has little or no effect on straight lines or smooth curves. But it has a drastic effect on corners and jaggy lines (see Figure 9-31). Smooth looks at each pixel in your selection, then looks at the pixels surrounding it (the number of pixels it looks at depends on the Radius value you choose in the Smooth dialog). If more than half the pixels around it are selected, then the pixel remains selected. If fewer than half are selected, the pixel becomes deselected.

If you enter a small Radius value, only corner tips and other sharp edges are rounded out. Larger values make sweeping changes. It’s rare that we use a radius over 5 or 6, but it depends entirely on what you’re doing (and how smooth your hand is!).

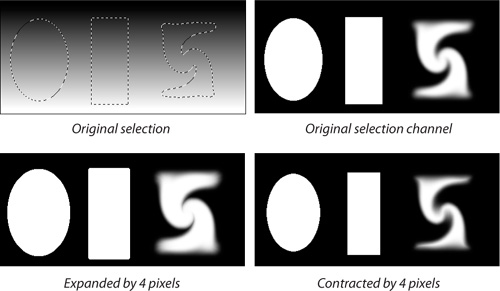

Expand and Contract. The Expand and Contract features are two of the most useful selection modifiers. They let you enlarge or reduce the size of the selection. This is just like spreading or choking colors in trapping (if you don’t know about trapping, don’t worry; it’s not relevant here).

Once again, these modifiers are simply applying filters to the black-and-white mask equivalent of your selection. Choosing Expand is the same as applying the Maximum filter to the mask; choosing Contract is the same as applying the Minimum filter (see Figure 9-32).

Note that if you enter 5 as the Radius value in the Maximum or Minimum dialog (or in the Expand or Contract dialogs), it’s exactly the same as running the filter or selection modifier five times. The Radius value here is more of an “iteration” value; how many times do you want the filter applied at a 1-pixel radius?

While we frequently find these selection modifiers useful, they aren’t very precise. You can only specify the radius in 1-pixel increments. For a lot more control, use the Refine Edge dialog instead.

We’ve talked about making selections; we’ve talked about saving channels; now it’s time to delve into masks—specifically: transparency masks, layer masks, and using layers as a mask. But as you read the following pages, don’t forget that masks are just channels, which are 8-bit (or 16-bit) grayscale images. Photoshop also lets you build a hard, vector-edged mask that is not based on a channel, called a vector mask; we’ll discuss this in “Shapes and Vector Masks,” in Chapter 11, “Essential Image Techniques.”

Most of the time when you create a new layer, the background is transparent. When you paint on it or paste in a selection, you’re making pixels opaque. Photoshop is always keeping track of how transparent each pixel is—fully transparent, partially transparent, or totally opaque. This information about pixel transparency is called the transparency mask (see Figure 9-33).

Remember the analogy we made to masking tape earlier in the chapter? The selection/channel/mask (they’re all the same) acts like tape over or around your image. In this case, however, the mask doesn’t represent how selected a pixel is; it’s how transparent (or, conversely, how visible) it is. You can have a pixel that’s fully selected but only 10 percent opaque (90 percent transparent).

It’s hard to emphasize in print just how important nondestructive editing is in our workflow. Perhaps you’re compositing several images on a background, or you’re retouching an image, or you’re adjusting the hue and brightness of a photograph. Whatever the case, you know that after hours of sweat and mouse-burn, when you show the result to your art director, she’s going to say, “Move this over a little, and we need a little more of this showing here, and you shouldn’t have changed the color of this part....”

Fortunately, you can use layer masks to avoid this sort of nightmare in your work. Layer masks are just like transparency masks—they determine how transparent the layer’s pixels are—but you can see layer masks and, more importantly, edit them (see Figure 9-34). If you had used nondestructive layer masks, instead of erasing or editing your original pixels, you would have smiled at your art director and made the changes quickly and painlessly. Here’s how you do it.

Creating and editing layer masks. To apply a layer mask to a selected layer, choose Layer > Add Layer Mask. When a layer has a mask, it can have only one (or two, if you include layer clipping paths)—the Layers palette displays a thumbnail of the mask (see Figure 9-35).

Faster layer masks. While there’s no built-in keyboard shortcut to add a layer mask (you can assign one if you want), it is a little faster to click on the Add Layer Mask icon in the Layers palette. If you Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) on the Add Layer Mask icon, Photoshop inverts the layer mask (so that it automatically hides everything on the layer).

Note that you can make a selection before clicking on the icon. In this case, the program “paints in” the unselected areas with black for you (on the layer mask). This is usually much easier than adding a layer mask, then using the paint tools to paint away areas. Of course, Option-clicking (Mac) or Alt-clicking (Windows) on the icon with a selection paints the selected areas with black, so that whatever was selected “disappears.”

Tip

To fade an effect across a layer (such as an adjustment layer in which you want to affect only the sky), use the Gradient tool to add a gradient to the layer mask. If the gradient isn’t quite right, open the Levels or Curves dialog and make adjustments to the layer mask itself. These tonal adjustments to the mask give you almost infinite control over how your effect is applied.

At first, it’s difficult to tell whether you’re editing the layer or the layer mask. But there are two differences: The layer mask thumbnail has a dashed border around it (on a high-resolution screen, the two borders look about the same) and the document title bar says “Layer x Mask.” We typically glance at the title bar about as often as we look in our car’s rear-view mirror; it’s a good way to keep a constant eye on what’s going on around us.

Editing a mask is as simple as painting with grays. Painting with black on the layer mask is like adding masking tape; it covers up part of the adjoining layer (making those pixels transparent). Painting with white takes away the tape and uncovers the layer’s image. Gray, of course, partially covers the image.

Tip

By default, moving a layer also moves its layer mask. To move them independently, turn off the Link icon (click between the layer and layer mask previews in the Layers palette).

Paint it in using masks. Layer masks let you paint in any kind of effect you want. For example, duplicate the Background layer of an image in the Layers palette, apply a filter to the new layer (like Unsharp Mask), then Option/Alt-click on the Add Layer Mask icon to mask out the entire effect. Now you can paint the effect back in using the Brush tool and non-black pixels. If you change your mind, you can paint away the effect with black pixels. This flexibility is addictive, and you’ll soon find yourself using this technique over and over, whether it’s painting in texture, sharpening or blurring, or whatever.

Getting rid of the mask. As soon as you start editing layer masks, you’re going to find that you want to turn the mask on and off so you can get before-and-after views of your work. You can make the mask disappear temporarily by choosing Layer > Layer Mask > Disable. Or do it the fast way: Shift-click on the Layer Mask icon.

Tip

If you used to press Command-G (Mac) or Ctrl-G (Windows) to create a clipping mask, note that you now need to add the Option key (Mac) or Alt key (Windows). This is because the old shortcut was reassigned to the Layer > Group Layers command for consistency with other applications. If you want it to work the old way, simply redefine the shortcut using Edit > Keyboard Shortcuts.

If you want to hide the mask with extreme prejudice—that is, if you want to delete it forever—choose Layer > Layer Mask > Delete (or, faster, drag the Layer Mask icon to the Trash icon). Photoshop gives you a last chance to apply the mask to the layer. Note that if you do apply the mask, the masked (hidden) portions of the layer are actually deleted.

All layer masks go away when you merge or flatten layers.

Layer mask shortcuts. When you’re working on a layer, you can jump to the layer mask (which is making it active, so all your edits are to the mask rather than the image) by pressing Command- (Mac) or Ctrl- (Windows). When you’re ready to leave the layer mask, press Command-~ (tilde) (Mac) or Ctrl-~ (Windows) to switch back to the composite view.

If you Option-Shift-click (Mac) or Alt-Shift-click (Windows) the Layer Mask icon in the Layers palette (or just press the key—that’s the backslash), Photoshop displays the mask and the layer, as if you’re in Quick Mask mode. If you don’t like the color or opacity of the layer mask, you can Option-Shift-double-click (Mac) or Alt-Shift-double-click (Windows) the icon to change the mask’s color and opacity. Then, when you’re ready to see the effects of your mask editing, Option-Shift-click (Mac) or Alt-Shift-click (Windows) the icon again to “hide” it (or press backslash again). If you want to see only the layer mask (as its own grayscale channel), Option/Alt-click its icon. This is most helpful when touching up areas of the layer mask (it’s sometimes hard to see the details in the mask when there’s a background image visible).

Tip

The fastest way to load the transparency mask for a layer as a selection is to Command/Ctrl-click on the layer’s thumbnail in the Layers palette. For instance, if you want to create a selection from text on a type layer, Command/Ctrl-click on the type layer’s thumbnail. This loads the selection, and you’re ready to roll.

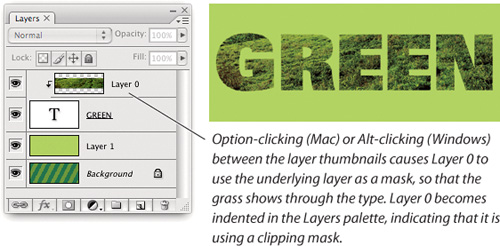

Layers not only have masks, but they can act as masks for other layers. The trick is to use clipping masks. Normally, putting one layer above another obscures the lower layer. When you create a clipping mask, the lower layer acts as a mask for the upper layer, so that the upper layer appears only where the lower layer is visible (see Figure 9-36).

To create a clipping mask, first position the content layer immediately above the mask layer in the Layers palette (you can’t do this with more than two layers), and then do one of the following.

Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) between their thumbnails in the Layers palette.

Press Command-Option-G (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-G (Windows), which is a shortcut for Layer > Create Clipping Mask.

It’s possible to have multiple layers indented above the clipping mask, in case you want one clipping mask to affect multiple layers.

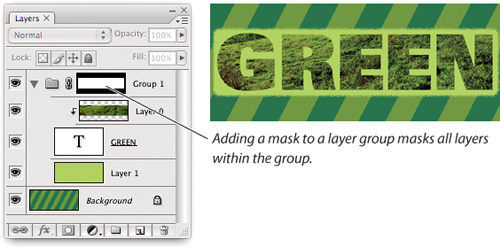

A layer group can have a mask, and that’s handy for creating nested masks. Select the layers, group them by pressing Command-G (Mac) or Ctrl-G (Windows), which is the shortcut for choosing Layer > Group Layers, and then add a mask to that layer group (see Figure 9-37).

If there’s one thing that makes silhouettes difficult, it’s the edge detail. In most cases (especially when you’re trying to select fine details), some of the color from the image background spills over into the image you want, which causes an obvious fringe when you drop the silhouetted image onto a different background (even white). While the addition of Refine Edge goes a long way toward automating these processes, we sometimes find it more effective to use the old-school manual methods of massaging selections with the full range of image-processing capabilities in Photoshop.

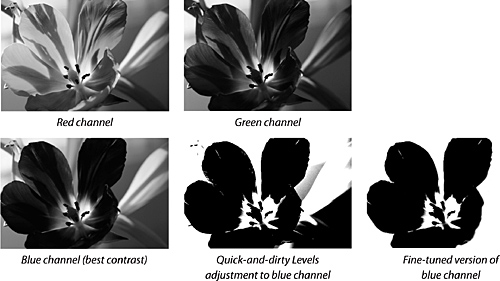

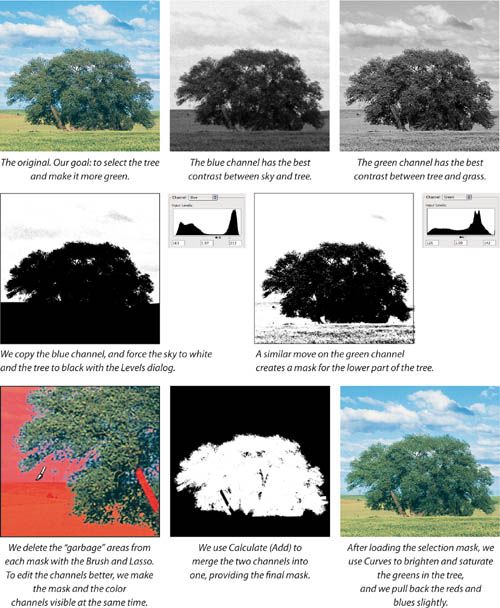

Trying to build a selection mask for the tree in Figure 9-38 with the basic selection tools would drive you to distraction faster than having to watch Barney and Friends reruns with your four-year-old. Instead, we found the essence of a great selection hiding in the color channels of the image. While you can often pull a selection mask from a single channel, in this case we made duplicates of both the blue and green channels. Then, using Levels, we pushed the tree to black and the background to white. After combining the two channels, it took only a little touch-up to complete the mask.

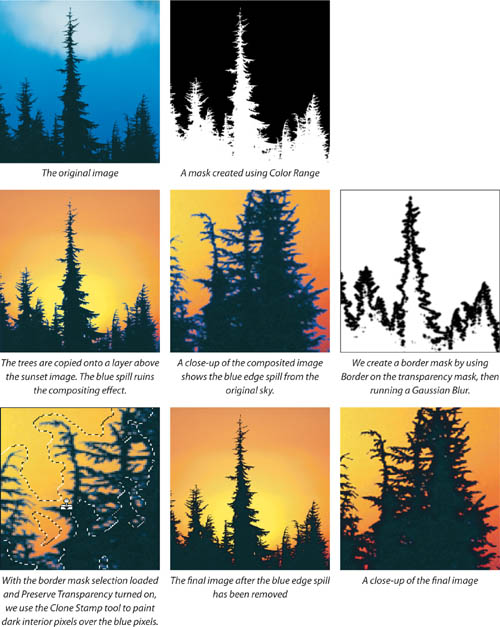

Edge spill is insidious, and—as you saw in the last example—it can be a disaster when compositing images. Here’s one more method for removing spill that we like a lot. If you place the pixels on a transparent layer, you can make use of the Preserve Transparency feature in the Layers palette to “paint away” the edge spill.

In the example in Figure 9-39, the color from the blue sky is much too noticeable around the composited trees. So we place the trees on a layer and build a selection that encompasses just their edges. This step is really just a convenience—it makes our job of painting out the edge spill easier. With Preserve Transparency turned on, we select the Clone Stamp tool and clone interior colors over the blue edge pixels. In some areas, we also use Curves to pull the blue out (because our border selection is feathered, these moves affect only the pixels we’re after).

Tip

Two filters can help you create selections by enhancing edges: Find Edges and High Pass. We typically duplicate the image we’re working on, then use one or more filters on the copy to extract the selection we want. Find Edges can bring out edges that are hard to see onscreen. The trick to using High Pass is to use very small values in the High Pass dialog, usually less than one or two pixels. Then, you can use the Levels or Curves dialog to enhance the edges by increasing the contrast of the image.

This is a trick you can use with all sorts of variations. If the edge color is relatively flat, you might be able to use the Brush tool (we usually add a little noise after painting in order to match the background texture); this is also an area where it behooves you to test out different Apply modes (Lighten, Multiply, and so on).

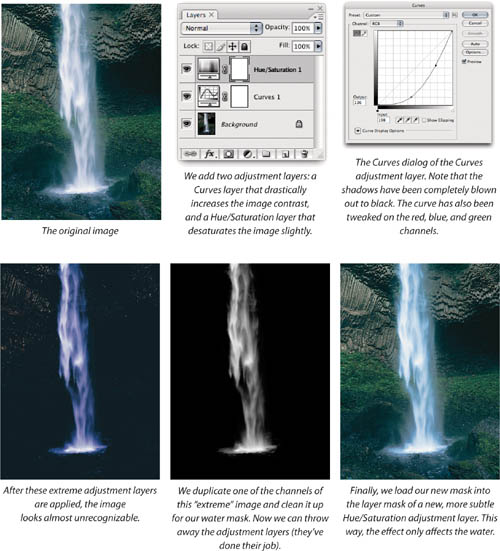

Adjustment layers are almost always used for tonal or color adjustments (we talk about adjustment layers in quite some detail in Chapter 8), “The Digital Darkroom.” But here’s a method that Greg Vander Houwen showed us that uses adjustment layers to help make selections. This is particularly useful when you’re trying to select a foreground image out of a background, and the two are too similar in color (see Figure 9-40).

First, add an adjustment layer above the image. You can make a radical adjustment in this layer and know that you’re not actually hurting your original image data. Boost the contrast between the foreground and background so that you can make a better selection.

After working with the Photoshop selection tools for a while, you begin to know instinctively when you’re up against a difficult task. For instance, trying to create a selection mask for a woman in a gauzy dress, with her long, wispy hair blowing in the wind, could be a nightmare. And if you have to perform 20 of these in a day...well...’nuf said. It’s time to plunk down some cash for one of the several masking programs on the market—for instance, Mask Pro from OnOne Software or KnockOut from Corel.

We’re not saying that these plug-ins are perfect. In fact, far from it. But they can often get you 90 percent of the way to a great selection in 10 percent of the time it would take you with Photoshop itself.