The biggest speed boost you can give to Photoshop is to accelerate your own productivity. If you get paid by the hour, rather than by the amount of work accomplished, you may want to skip this chapter. If you want to realize the full potential of Photoshop as a lean, mean, pixel-processing machine, read on! We’ll break you of the habit of choosing tools by clicking on their icons, and help you avoid those lengthy mouse voyages up to the menu bar.

As applications pile on the palettes and options, screen space remains a premium even as monitor sizes grow. Space is an even bigger challenge if you need to manage multiple windows. Use these tips to shuffle and stack windows as expertly as a Las Vegas casino dealer.

Screen modes. Click and hold the Screen Mode icon at the bottom of the Tools palette to see four screen modes. We like to cycle through the modes by pressing F. You can also pick a screen mode from the Screen Mode submenu (under the View menu), but the other ways are so much more convenient that you’ll probably go to the View menu only if you’re recording an action that plays back a screen mode change.

In addition to the Standard Screen Mode (regular windows), Full Screen Mode (black background with no menu bar) and Full Screen Mode with Menu Bar (gray background), Photoshop CS3 adds a new Maximized Screen Mode (see Figure 6-1)—a middle ground between Standard Screen Mode and the two full screen modes. As you show and hide palettes, Maximized resizes the document workspace so that it always stays out of the way of the open palettes. Maximized Screen Mode may throw off veteran Mac Photoshop users, because it is unlike either the Standard or Full Screen modes that existed in previous versions. Think of Maximized as Full Screen Mode with scroll bars. Maximized is actually welcomed by many who’ve switched from Windows to the Mac, because Maximized is a standard feature in Windows. We like to work in Full Screen mode instead of wasting space on title bars, scroll bars, and the like.

Note

In Photoshop CS2, each document window could have its own screen mode. In Photoshop CS3, changing the screen mode affects all document windows.

Changing the surrounding color. All modes surround the document with gray except for Full Screen mode, which is black. To change this, Control-click (Mac) or right-click (Windows) the surrounding area and choose an option from the context menu that appears. You can also change the surrounding color by Shift-clicking the Paint Bucket tool, but frankly, that’s more work because we can never remember where the Paint Bucket is hiding in the Tools palette. (Psst... it’s under the Gradient tool.)

Tip

If you used Photoshop CS2, you may be wondering how to show and hide the menu bar. The old Shift-F shortcut in CS2 no longer works in Photoshop CS3. Instead, switch to Full Screen Mode with or without the menu bar, and change the surrounding color if needed.

Full Screen scroll. Just because your image is in Full Screen mode doesn’t mean you can’t scroll around: Just hold down the spacebar (to get the Hand tool) and drag. In the Full Screen mode, you can use the Hand tool to slide past the edge of the image into the gray or black area, no matter how far you’re zoomed in; going past the edge is something scroll bars can’t do (see Figure 6-2). Scrolling past the image edge is useful when you’re cropping or retouching close to the edge of an image, and it’s a big reason Conrad prefers the Full Screen mode over the Maximized mode.

Tip

If a document opens at too low of a magnification, try closing palettes. Photoshop wants to show you the whole document when you first open one, and there’s less space to show everything when more palettes occupy the workspace.

Tidy up your windows. When you have multiple document windows open, Photoshop will neatly arrange them on your screen if you choose Tile Horizontally, Tile Vertically, or Cascade from the Arrange submenu (under the Window menu). The Tile commands display windows side-by-side, while Cascade stacks the windows with a slight offset.

Flip through the windows. We often find ourselves in Photoshop with five or more windows open at a time—a frustrating situation when we need to move through them all quickly. You can press Control-Tab to switch from one open document to the next. (In this case, it’s the Control key on both Mac and Windows.) This way, you can rotate through the windows without taking your hands off the keyboard, even if you’re in Full Screen mode with no menus.

Two windows on the same document. Are you often jumping back and forth between two views? For example, between different magnifications, color modes, or preview modes? If so, consider opening a second window by selecting New Window from the Arrange submenu (under the Window menu). Whenever you change something in one window, Photoshop updates the other window almost immediately.

From window to folder. To open another image in the same folder as a document currently open in Photoshop in Mac OS X, Command-click on the title in the document window’s title bar and select the folder from the pop-up menu that appears. This tells Photoshop to switch to the desktop and open that folder. In Windows, you can see a document’s folder path by holding the cursor over a document’s title bar until a tool tip appears.

In this section, we first explore some of the fastest ways to move around your image, including zooming in and out. Then we discuss moving pixels around both within your document and from one document to another. It’s funny, but we find that even expert users forget or never learn this basic stuff, so we urge you to read this section even if you think you already know all there is to know about navigating Photoshop.

Images have pixels. Computer monitors have pixels. But how does one type of pixel relate to the other type of pixel? When one image pixel is displayed on one monitor pixel, you’re seeing every detail of the image. In Photoshop, this happens at 100 percent magnification, or the Actual Pixels command under the View menu. This view doesn’t necessarily tell you how big the image will appear in print or even on the Web, because different monitors have different resolutions.

At 400 percent, the image is magnified four times, so each image pixel is displayed using 16 monitor pixels (see Figure 6-3). At 50 percent, you’re seeing only one-quarter of the pixels in the image, because zooming out causes Photoshop to downsample four image pixels to one monitor pixel. At any percentage other than 100, you’re not seeing a fully accurate view of your image, because you aren’t seeing the exact number of pixels in the image.

When you’re viewing at an integral multiple of 100 (25, 50, 200, 400 percent, and so on), Photoshop displays image pixels evenly. At 200 percent, four screen pixels (two horizontal, two vertical) equal one image pixel; at 50 percent, four image pixels equal one screen pixel, and so on. However, when you’re at any “odd” percentage, the program has to jimmy the display in order to make things work. Photoshop can’t cut a screen pixel or an image pixel in half, so instead it fakes the effect using anti-aliasing. Magnifications lower than 100 percent can give you a distorted view of resolution-dependent effects, such as sharpening.

The moral of the story is that you should always return to the Actual Pixels (100 percent) view to get the most accurate view of your image. You’ll be doing this all the time, so learn the shortcuts: Command-Option-0 (zero) (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-0 (Windows), or double-click the Zoom tool in the Tools palette.

Don’t select the zoom tool. We never select the Zoom tool from the Tool palette because it takes too long. You can temporarily switch to the Zoom tool by holding down Command-spacebar to zoom in or Command-Option-spacebar to zoom out (Mac), or Ctrl-spacebar to zoom in or Ctrl-Alt-spacebar to zoom out (Windows). Each click is the same as choosing Zoom In or Zoom Out from the View menu.

Drag to zoom. When you drag a rectangle using the Zoom tool, the area you drag magnifies to fill the window.

Zoom with keyboard shortcuts. If you just want to change the overall magnification of an image, zoom in and out by pressing Command-+ (plus sign) or Command-− (minus sign) in Mac OS X, or by pressing Ctrl-+ (plus sign) or Ctrl-− (minus sign) in Windows. When zooming, the window won’t extend under the edges of palettes; if you want this to happen, use one of the Full Screen modes. In Mac OS X, adding the Option key to this mix tells Photoshop to zoom in or out without changing the size of the window. For some reason, it’s just the opposite in Windows: The Ctrl key zooms without resizing, and holding down Ctrl and Alt zooms and resizes. In any case, if you want the opposite behavior to be the default, disable the Zoom Resizes Windows check box in the General Preferences dialog.

Zoom with the scroll wheel. If your mouse has a scroll wheel, you can use it to scroll or zoom. By default, it’s set to scroll, and pressing Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) makes the scroll wheel zoom instead. To reverse this behavior, check Zoom with Scroll Wheel in General Preferences.

Fit image within screen. Double-clicking on the Hand tool is the same as clicking Fit Screen in the Options bar when the Zoom tool or Hand tool is selected, or pressing Command-0 (zero) (Mac) or Ctrl-0 (Windows)—it makes the image and the document window as large as it can without going outside the screen’s boundaries. The image may not zoom to the full width or height of the monitor if palettes are present.

Zoom field in the document window. At the bottom left corner of the window, Photoshop displays the current magnification percentage. This isn’t only a display; you can change it. Double-click to select the whole field, type the zoom percentage you want, then press Return or Enter. If you’re not sure what percentage you want, press Shift-Return instead of Return and the field will remain selected so you can enter a different value (see Figure 6-4).

Using Print Size magnification. Generations of Photoshop users have been baffled by the View > Print Size command, mostly because when you choose it, it never matches the size of the image when you actually print it! Well, never say never; there is a way to make it work. The only way the Print Size command can know the actual print size is to know the resolution of your monitor, so that the rulers become accurate. To make Print Size work right, do the following:

Open the Displays system preference (Mac) or the Displays control panel (Windows), and note your monitor’s current resolution setting (for example, 1280 × 854 pixels).

Grab an actual, real-world ruler and measure the width of your monitor image (not the frame in inches). Be careful not to scratch your screen!

Divide the horizontal pixel dimension of your monitor by the horizontal real-world dimension of your monitor. For example, my wide-screen LCD monitor is set to 1680 pixels across a physical width of 17 inches, and 1680/17 = 98.8 pixels per inch.

Open the Preferences dialog, click the Units and Rulers pane, and enter your pixels per inch value into the Screen Resolution field (see Figure 6-5).

Now when you choose View > Print Size, Photoshop can take into account both your screen resolution and the resolution of the image in the Image > Image Size dialog, and correctly display the printed size of the image. Another wonderful result of all this is that your rulers now match the real world at Print Size magnification. If the rulers don’t match exactly, adjust the Screen Resolution field slightly until they do.

If you’re like most Photoshop users, you find yourself moving around the image a lot. Do a little here . . . do a little there . . . and so on. But when you’re doing this kind of navigation, you should rarely use the scroll bars. There are much better ways.

Tip

To use the Zoom or Hand tool on every open image window at the same time, hold down the Shift key as you click the Zoom tool or drag the Hand tool.

Use the Hand. The best way to make a small move around your image is to select the Hand tool with your keyboard (by pressing the spacebar) instead of choosing it from the Tool palette. Then just click-and-drag to where you want to go.

End Up Down Home. Many people ignore the very helpful Page Up, Page Down, Home, and End keys when working in Photoshop, but we find them invaluable for perusing an image for dust or scratches.

When you press Page Up or Page Down, Photoshop scrolls the image by one whole window of pixels up or down. While there’s no Page Left or Page Right button, you can jump one window of pixels to the left or right by pressing Command-Page Up or Command-Page Down in Mac OS X, or Ctrl-Page Up or Control-Page Down in Windows. You can scroll in 10-pixel increments by adding the Shift key to any of the shortcuts above.

Also note that pressing the Home button jumps you to the top left corner, and the End button jumps you to the bottom right corner of the document. David often uses this technique when using the Crop tool to quickly adjust the top left and bottom right corners.

If you’re on a laptop, these keys may be overlaid with the arrow keys. For example, on a Mac laptop, the Up Arrow key also has Page Up printed on it. To use the Page Up function of that key, add the Fn key at the bottom left corner of the keyboard, so that you press Fn-Up Arrow to get Page Up.

Match up your windows. When you’re working on multiple images at the same time, it’s often helpful to sync up their views. Several commands on the Arrange submenu (under the Window menu) automate this process. The Match Zoom feature sets the magnification percentage for every open image to the zoom level of the current document. Match Location leaves the magnification alone but scrolls each document window to the same part of the image as the current file. For instance, if the current file displays the lower-right corner, then all the images will scroll to the lower-right corner. (Unfortunately, Match Location is only approximate; it won’t match to the exact pixel.) The one we use most often is Match Zoom and Location. You can guess what it does.

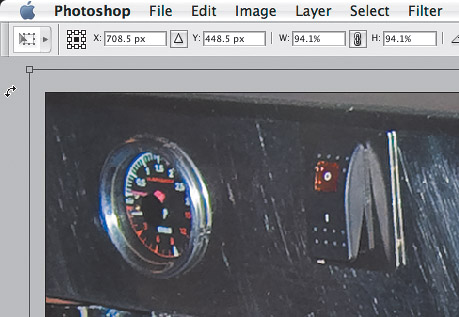

Context-sensitive menus. When you Control-click (Mac) or right-click (Windows), Photoshop displays a context-sensitive menu that changes depending on what tool you have selected in the Tool palette; it’s worth trying out with any tool you use (see Figure 6-6).

For brush or retouching tools, the context menu is a quick way to adjust the brush. The context-sensitive menu for the Move tool lets you select a layer. If you have four layers in an image and three of them overlap in one particular area, you can Control-click (or right-click) on that area and Photoshop asks you which of the three layers you want to jump to. If the Move tool isn’t selected, you can almost always get the Move tool’s context menu by Command-Control-clicking in Mac OS X, or Ctrl-right-clicking in Windows.

The context-sensitive menu for the Marquee tool contains a mishmash of features, including Delete Layer, Duplicate Layer, Load Selection, Reselect, Color Range, and Group into New Smart Object (we have no idea why Adobe picked these and left others out). Many of these features don’t have keyboard shortcuts, so this menu is the fastest way to perform them.

You can use the Navigator palette as command central for all scrolling and zooming (see Figure 6-7). However, we rarely use this palette because we zoom much faster with the keyboard shortcuts, but if you get along with the Navigator palette, don’t let us stop you from using it.

A thumbnail of the image fills most of the palette, with a red frame marking the contents of the active window. (If your image has a lot of red in it, you might want to change the frame color by choosing Palette Options from the Palette menu). Dragging the outline pans the contents of the active window. Command-dragging (Mac) or Ctrl-dragging (Windows) lets you define a new outline, thereby changing the zoom percentage.

The percentage field at the lower left of the palette works exactly like the one at the lower left of the image window. You can click the Zoom In and Zoom Out buttons instead of using the keyboard shortcuts for zooming. David’s favorite feature in this palette is the magnification slider, which lets him change the zoom level dynamically, but you can also do that by scrolling a mouse wheel while pressing Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows).

Before we talk about moving things around, it’s useful to understand that in Photoshop, multiple types of moves can be available at any one time. For instance, if you’ve selected an area on a layer, at that moment you can move the selection boundary or the selected pixels, and the way you want to go dictates which tool or keyboard shortcut you use.

If you simply make a selection and then drag it with one of the selection tools, you move the selection boundary but not the selected pixels. If you want to move the pixels, use the Move tool (press M). No matter what tool is selected, you can always temporarily get the Move tool by holding down the Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) key.

When you move or copy selected pixels with the Move tool, you get a floating selection, which is like a temporary layer that disappears when you deselect. While the selection is still floating, you can use the Fade command (in the Edit menu) to change its opacity or blend mode.

With the Move tool, you don’t have to worry about positioning the cursor first—just drag anywhere within the document window. This is a great speedup, especially when you’re working with heavily feathered selections. Also, if you want to move an entire layer and the layer is already selected in the Layers palette, you can use the Move tool to drag the entire layer right away, without using a selection tool or the command first.

Our selection tips don’t apply only to selected pixels. They’ll also work on objects like a selected path, or on the currently selected layer or layer mask in the Layers palette. Most of the tips also work on the selection boundary itself if you choose Edit > Transform Selection first.

Moving precisely. If it’s hard to keep your hand steady when working precisely, try the arrow keys and the Options bar instead of the mouse.

With the Move tool selected, each press of an arrow key moves the layer or selection by one pixel. If you add the Shift key, the selection moves 10 pixels. Modifier keys work, too: Hold down the Option key (Mac) or Alt key (Windows) when you first press an arrow key, and the selection is duplicated, floated, and moved one pixel (don’t keep holding down the Option/Alt key after that, unless you want a lot of duplicates). Remember that you can always get the Move tool temporarily by adding the Command key (Mac) or Ctrl key (Windows) to any of these shortcuts.

To move an object or layer precisely by entering X and Y coordinates, first choose Edit > Free Transform. (If you’re moving the selection boundary, choose Select > Transform Selection instead.) Then enter new X and Y coordinates in the Options bar.

Moving multiple layers. Layers are great, but you often can’t do the same thing to more than one layer at the same time. Fortunately, moving layers is easy: Simply select more than one layer in the Layers palette. If you’ve ever selected multiple files in a folder on your desktop, it’s the same thing in the Layers palette: Shift-select the first and last layers; to select a discontiguous range, Command-click (Mac) or Ctrl-click (Windows) each layer you want to add to the selection.

Copying pixels. If you select pixels and choose Edit > Copy, you only get the pixels on the currently active layer(s) (the one(s) selected on the Layers palette). To copy selected pixels across all visible layers, select Copy Merged instead (Command-Shift-C in Mac OS X, Ctrl-Shift-C in Windows).

Some people use this technique to make a merged copy of the entire image (not just a selection). It works, but remember that when you can achieve the same result using the clipboard and using layers, layers are usually faster and use less RAM. The fastest and most efficient way to merge all layers into a new document is to choose Layer > Duplicate Layers, and choose New from the Destination pop-up menu to merge all layers and send them to a new document in one step.

Tip

Making a selection and using the Paste Into command (or the Paste Outside feature that you get by adding the Shift key) lets you create both a layer and a layer mask in one step.

Pasting pixels. In the most common color modes, such as RGB and CMYK, pasting pixels into a document automatically creates a new layer. When a selection is active, you’ll also see the Edit > Paste Into command (Command-Shift-V in Mac OS X, or Ctrl-Shift-V in Windows), which adds a new layer with a layer mask based on the selection so that the pixels you’re pasting appear only inside the selection. If you add the Shift key to the Paste Into keyboard shortcut, the pixels you’re pasting appear only outside the selection, because adding Shift inverts the layer mask that’s created.

Drag and Drop Selections and Layers. To move selected pixels (or a layer) from one document to another, drag it from one window into the other (if you’ve got a selection, remember to use the Move tool, or else you’ll just move the selection boundary itself). Again, dragging requires less memory than copying and pasting. If you’re trying to copy an entire layer, you can also just click its thumbnail in the Layers palette and drag it to the other document’s window. Either way, if you want to drop the selection smack in the exact center of the destination document, Shift-drag instead.

Moving pixels is all very well and good, but where are you going to move them? If you need to place pixels with precision, you should use the ruler, guides, grids, and alignment features. The ruler is the simplest: you can hide or show it by pressing Command-R (Mac) or Ctrl-R (Windows). Wherever you move your cursor, you can track the cursor position using the tick marks appear in the rulers (or the coordinates on the Info palette).

Guides. You can add a guide to a page by dragging it out from either the horizontal or vertical ruler. Or, if you care about specific placement, you can watch the ruler tick marks or the Info palette coordinates, or select View > New Guide so you can type in a numerical position. (If you don’t think in inches, you can change the default measurement system; see “Switch Units,” later in this chapter.) Table 6-1 lists a number of grids and guides keystrokes that can help you use these features effortlessly.

Table 6-1. Grids and guides keystrokes

To do this . . . | Press this . . . |

|---|---|

Hide/Show Extras (grids, guides, etc.) | Command-H (Mac) Ctrl-H (Windows) |

Hide/Show Guides | Command-’ (apostrophe) (Mac) Ctrl-’ (Windows) |

Hide/Show Grid | Command-Option-’ (Mac) Ctrl-Alt-’ (Windows) |

Snap To Guides | Command-; (semicolon) (Mac) Ctrl-; (Windows) |

Lock/Unlock Guides | Command-Option-; (Mac) Ctrl-Alt-; (Windows) |

Snap to ruler marks. We almost always hold down the Shift key when dragging a guide out from a ruler; that way, the guide automatically snaps to the ruler tick marks. If you find that your guides are slightly sticky as you drag them out without the Shift key held down, check to see what layer you’re on. When Snap To Guides is turned on, objects snap to the guides and guides snap to the edges and centers of objects on layers.

Switching guide direction. Dragged out a horizontal guide when you meant to get a vertical one? No problem: Just Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) the guide to switch its orientation (or hold down the Option/Alt key while dragging the guide out of the ruler).

Mirroring guides. If you rotate your image by 90 degrees, or flip it horizontally or vertically, your guides will rotate or flip with it. If you don’t want this to happen, choose View > Lock Guides, or press Command-Option-; (Mac) or Command-Option-; (Windows).

Guides outside the image. Just because your pixels stop at the edge of the image doesn’t mean your guides have to. You can place guides out on the area surrounding the image and they’ll still be functional. This is just the ticket if you’ve got a photo that you need to place so that it bleeds off the edge of your image by 0.25 inch.

Change guides and grids. Guides are, by default, cyan. Grid lines are, by default, set one inch apart. If you don’t like these settings, change them in the Guides, Grid & Slices pane of the Preferences dialog, or just double-click any guide with the Move tool.

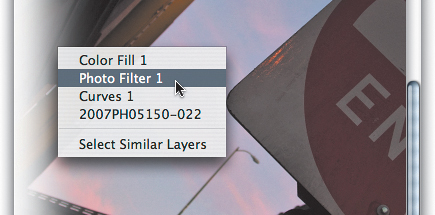

Alignment and distribution. People often use the alignment features in page-layout applications, but Photoshop has alignment and distribution features, too, and they’re a godsend for anyone who really cares about precision in their images. Alignment lines up layers, and distribution spaces layers evenly between the two outermost selected layers. Here’s how you can align or distribute layers:

Select two or more layers in the Layers palette.

If you want the layers to align or distribute to each other, make sure no pixels are selected by choosing Select > Deselect or press its shortcut, Command-D (Mac) or Ctrl-D (Windows).

If you want layers to align or distribute within a specific area, use the Rectangular Marquee tool to drag a selection boundary. To align or distribute to the canvas size, make sure the Background layer is one of the selected layers, or choose Edit > Select All. When a selection exists, the Layer > Align command changes to Align Layers to Selection.

Press V to activate the Move tool, and then click on one of the Align buttons in the Options bar (see Figure 6-8). Alternatively, you can also Choose Layer > Align or Layer > Distribute and then choose a command from the Align submenu.

Aligning or distributing to a specific object. Normally, when you align along the left edges, Photoshop moves all the layers except for the one that has the leftmost data (or the rightmost data when aligning left, and so on). You can force Photoshop to lock one layer and move the others by linking the layers: Select the layers, click the Link icon at the bottom of the Layers palette, then click on the layer you want to remain in place. Now when you choose from the Align or Distribute submenu, all the layers move except for the currently selected layer.

When distributing layers vertically, Photoshop “locks” the layers that are closest to the top and the bottom of the image canvas; when distributing horizontally, it locks the leftmost and rightmost layers. All the layers in between get moved. For example, if you choose Vertical Centers from the Distribute Linked submenu, Photoshop moves the layers so that there is an equal amount of space from the vertical center point of one layer to the next.

Dialogs seem like simple things, but since you probably spend a good chunk of your time in Photoshop looking at them, wouldn’t it be great to be more efficient while you’re there? Here are a bunch of tips that will let you fly through those pesky beasts.

Yes, you can. The most important lesson to learn about dialogs in Photoshop is that just because one is open doesn’t mean you can’t do anything else. For instance, if the Curves dialog is open, you can still scroll and zoom the document. Check the menu bar when a dialog is open—you can use any command that isn’t dimmed. For example, because palette commands are available on the Window menu, you can even open and close palettes when a dialog is open. The palette we end up opening most often from inside dialogs is the Info palette, because it gives us readouts of color values.

Scrub-a-dub-dub. You can edit values in dialogs by scrubbing, or dragging horizontally over a value. For example, if you’re in the Image Size dialog, hold down Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) as you position the mouse over any number field. When the cursor appears as a finger with a two-headed horizontal arrow, you can drag left to lower the value, or drag right to raise the value (see Figure 6-9). This also works in palettes that have number fields, including the Options bar. For faster scrubbing, hold down the Shift key, which multiplies the normal adjustment by ten.

Save your settings. Many dialogs in Photoshop have Save and Load buttons that let you save to disk all the settings that you’ve made in a dialog. They’re particularly useful when you want to use the same dialog settings on many images.

For instance, let’s say you’re adjusting the tone of an image with Curves. You increase this and decrease that, and add some points here and there... Finally, when you’re finished, you click OK and realize that you’d like to apply the same curve to 50 other images shot under the same conditions. Instead of laboriously reconstructing the same curve 50 times, just click the Save button in the Curves dialog to save the curve settings as a file. Now, from any other image, you can open the Curves dialog, click the Load button, and select the curves setting files you saved. This is especially useful when you build actions that automate your workflow, because you can have your action load a settings file. You can also send settings files to your colleagues so they can load them.

Instant replay. There’s one other way to undo and still save any tonal-adjustment settings you’ve made. If you hold down the Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) key while selecting a command from the Image > Adjust submenu, the dialog opens with the last-used settings. Similarly, you can add the Option/Alt key to the adjustment’s keyboard shortcut. For instance, in Mac OS X, Command-L is the shortcut for Levels, so Command-Option-L opens the Levels dialog with the same settings you last used. This is a great way to specify the same Levels or Curves (or Hue/Saturation, or any other adjustment) for several different images. But as soon as you quit Photoshop, it loses its memory.

Most of the tonal- and color-correction features and many filters offer a Preview check box in their dialogs. Plus, all the filters that have a dialog have a proxy window that shows the effect applied to a small section of the image (some dialogs have both). If you’re working on a very large file on a relatively slow machine, and the filter you’re using has a proxy window, you might want to turn off the Preview check box so that Photoshop doesn’t slow down redrawing the screen while you’re making adjustments. However, most of the time, unless we’re working with a very slow filter like Smart Sharpen, we just leave the Preview feature on.

We use the Preview check box to view “before” and “after” versions of our images, toggling it on and off to see the effect of the changes without leaving the dialog. (Sometimes the changes we make are subtle and gradual, but a before-and-after usually lets us see exactly what we’ve accomplished.) In Photoshop CS3, we now press the P key to toggle the Preview check box. If you loved this shortcut in Adobe Camera Raw and wished it were in Photoshop (like we did), Photoshop CS3 grants your wish. Pressing P for Preview works in most, but mysteriously not all, Photoshop CS3 dialogs.

The following tips don’t apply to the dialogs for the more creative filters, such as Dry Brush and Plastic Wrap. They use a different dialog that provides a large preview image inside the dialog but not in the main window. We don’t really cover those filters because they’re more about special effects, and we’re more about image correction.

Proxies. The proxy in dialogs shows only a small part of the image, but it updates almost instantly. Previewing time-consuming filters such as Smart Sharpen or Reduce Noise on a large file can take a long time. Some very time-consuming filters such as the Distort filters offer a large proxy instead of a preview.

Before and after in proxies. You can always see a before-and-after comparison by clicking in the proxy. Hold down the mouse button to see the image before the filter is applied, and release it to see the image after the filter is applied. This is obviously quicker than redrawing the whole window with the Preview check box.

Change the proxy view. To see a different part of the image, click-and-drag in the proxy (no modifier keys are necessary). Alternatively, you can click in the document itself. The cursor changes to a small rectangle and wherever you click shows up in the Preview window.

Similarly, you can zoom the proxy in and out. The slow way is to click on the little (+) and (-) buttons. Much faster is to click the proxy while pressing the Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) key to zoom in, or the Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) key to zoom out. However, we rarely zoom in and out because you see the true effect of a filter only at 100 percent view.

Note that proxies only show the layer you’re working on at any one time. This makes sense, really; only that layer is going to be affected.

We love keyboard shortcuts. They make everything go much faster, or at least they make it feel like we’re working faster. Here are a few shortcuts that we use all the time inside dialogs.

Option/Alt. Holding down the Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) key in a dialog almost always changes the Cancel button to a Reset button, letting you reset the dialog to its original state (the way it was when you first opened it). If you want to go keyboard shortcuts the whole way, press Command-Option-period to do the same thing (there’s no equivalent shortcut in Windows).

Command-Z/Ctrl-Z. You already know the shortcut Command-Z (Mac) or Ctrl-Z (Windows) because it’s gotten you out of more jams than you care to think about. You can use the same shortcut to undo within most dialogs, too. Inside dialogs, you get only one undo step.

Arrow keys. When a dialog contains a number field, you can change those numbers by pressing the Up or Down arrow key. Press once, and the number increases or decreases by one. If you hold down the Shift key while pressing the arrow key, the number changes by 10. (Note that some dialog values change by a tenth or even a hundredth; when you hold down Shift, they change by 10 times as much.) This is a great way to fine-tune adjustments without cramping your mouse hand.

A few dialogs use the arrow keys in a different way. In the Lens Flare filter, for instance, the arrow keys move the position of the effect.

Tab key. As in most Mac and Windows applications, the Tab key selects the next text field in dialogs with multiple text fields. Shift-Tab to move to the previous field instead.

P for Preview. As we mentioned a little earlier, press P to toggle the Preview check box in any dialog that has one.

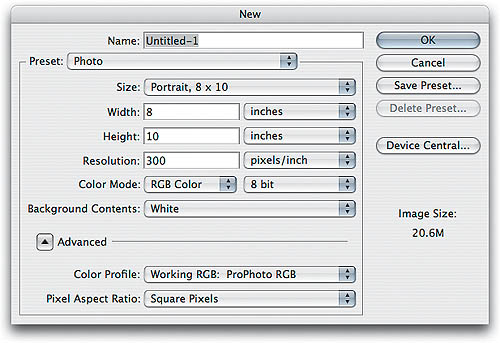

Before we move on to essential tips about tools, we need to take a quick look at the New dialog, which has a few very helpful (and in some cases hidden) features. For instance, note that the New dialog has an Advanced button; when you click this, you’re offered two additional settings: Color Profile and Pixel Aspect Ratio. Color Profile lets you specify a profile other than the working space for your image. (You can choose the default working space too, but since that’s what you’d get anyway, it’s a bit pointless to choose it here.) Note that we cover working spaces in Chapter 4, “Color Settings.” Pixel Aspect Ratio lets you use nonsquare pixels, in case your image is destined for video. If video isn’t in your game plan, then avoid this pop-up menu entirely.

Preset document sizes. The Preset pop-up menu in the New dialog lets you pick from among many common document sizes, such as A4, 640 × 480, and 4 × 6 inches. You may not see very many choices if you click the Preset pop-up menu, but that’s because it’s a two-stage process: First choose a category from the Preset pop-up menu, and then choose a size from the Size pop-up menu. If you need a preset other than the ones on the list, just set the New dialog the way you want it, then click the Save Preset button (see Figure 6-10). You can delete user-created presets using the Delete Preset button, but the built-in ones that ship with Photoshop are there to stay.

When you save a document preset, Photoshop gives you the choice of which settings to remember: Resolution, Mode, Bit Depth, Content, Profile, and Pixel Aspect Ratio. For example, let’s say you turn off the Profile check box; when you later choose your preset from the Preset pop-up menu, Photoshop leaves the image’s profile set to the current working space instead of overriding it.

Note that some built-in presets (those having to do with video), can also automatically add guides to the document. Unfortunately, there’s currently no way to save presets with guides yourself.

Clairvoyant image size. The New dialog tries to read your mind. If you have something copied to the Clipboard when you create a new document, Photoshop automatically selects Clipboard from the Preset pop-up menu and plugs the pixel dimensions, resolution, and color model of that copied piece into the proper places of the dialog for you. If you’d rather use the values from the last new image you created, hold down Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) while selecting New from the File menu, or press Command-Option-N (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-N (Windows).

Break up measurements. Photoshop is just trying to help make your life easier: When you select a measurement system (inches, picas, pixels, or whatever) in the New dialog—or the Image Size or the Canvas Size dialogs—Photoshop changes both the horizontal and vertical settings. If you want vertical to be set to picas and horizontal to be millimeters, then hold down the Shift key while selecting a measurement system. That tells the program not to change the other setting, too.

Copying sizes from other documents. In the New dialog, notice that all open documents are listed at the bottom of the Preset pop-up menu. If you want your new document to match an open document, simply choose the name of that document in this menu.

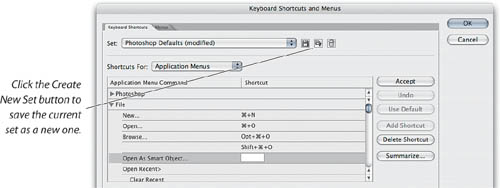

You can change keyboard shortcuts you don’t like, and you can add shortcuts where there weren’t any before. Of course, the ability to change keyboard shortcuts is great for you, but can wreak havoc for others using your machine. Fortunately, Photoshop lets you save keyboard shortcut sets, and you can include a set as part of a saved workspace that also includes your favorite palette arrangement and menu customizations.

Use your own set. To edit or add a keyboard shortcut, choose Edit > Keyboard Shortcuts or press Command-Option-Shift-K (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-Shift-K (Windows). If you edit the default set, it’s saved as “Photoshop Default (modified),” so you can still get the original default back (just choose Photoshop Defaults from the Set menu). We recommend giving sets useful names; otherwise they can be lost when you choose another set or if you need to reset your preferences while troubleshooting a problem. To save a new set, click the New Set button (see Figure 6-11); by default, Photoshop saves the set in the proper location on your hard drive (inside your Photoshop application folder, in Presets > Keyboard Shortcuts).

To customize keyboard shortcuts, follow these steps:

Pick Application Menus, Palette Menus, or Tools from the Shortcuts For pop-up menu.

Click an expansion triangle to reveal menu commands, and then select a command or tool from the list.

When the field in the Shortcut column is highlighted, you can type the keyboard shortcut you want to apply to this feature. If the shortcut is already in use, Photoshop alerts you and gives you choices.

If you want to create another shortcut for the same feature (there’s no reason you can’t have more than one shortcut that does the same thing), click the Add Shortcut button. If you’re done with this feature and want to change another, click the Accept button. When you’re done applying shortcuts, click OK.

Note that you can edit or add keyboard shortcuts for palette menus and tools in addition to regular menu commands. You can even save shortcuts for third-party features that appear as commands, such as Import and Automate plug-ins, filters, or scripts!

Tip

If you don’t want to apply a new keyboard shortcut and the Shortcut field is still highlighted, press Cancel to back out of the change. Be careful. If you press Cancel a second time, you’ll close the dialog without saving changes.

What was that shortcut again?. With the advent of editable keyboard shortcuts, the number of different shortcuts for you to keep track of threatens to overwhelm any mortal’s brain. Fortunately, you can click the Summarize button in the Keyboard Shortcuts and Menus dialog to export a list of every feature and its shortcuts. Photoshop saves this file in HTML format, so you can open it in any Web browser and you can print it.

Conflicts with system shortcut keys (Mac only). In Mac OS X, Apple appropriated two keyboard shortcuts that were crucial for Photoshop users: Command-H and Command-M. Photoshop users know these as the shorcuts for Hide Selection and Open Curves dialog. The Mac OS X folks use these shortcuts for Hide Application and Minimize Application. In Photoshop, the Photoshop keyboard shortcuts always win. However, you can hold down the Control key, too, to get the system shortcuts (press Command-Control-H to get Hide Application, and so on).

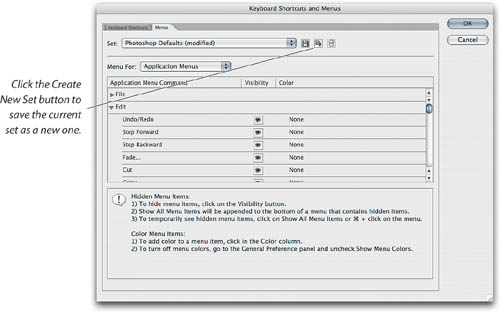

Photoshop is practically overflowing with menu commands. If you have trouble remembering which commands apply to your workflow, you can customize Photoshop menus by colorizing or hiding them. We think menu customization works best when you spend most of your time using Photoshop in a very specialized way, or when you’re trying to train yourself or others on a specific workflow.

To edit menu commands, choose Menus from the Edit menu or press Command-Option-Shift-M (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-Shift-M (Windows) to open the Keyboard Shortcuts and Menus dialog—it’s the same dialog used for customizing keyboard shortcuts, but when opened with the Menus command, it opens showing the Menus tab (see Figure 6-12). As with keyboard shortcuts, you can save your customizations as a set, and we recommend that you do so. Note that you can’t hide the Quit or Close commands in Photoshop.

After you’re finished moving around in your image, zooming in and out, and moving pixels hither and yon, it’s time to get down to work with the tools in Photoshop. The tools have all sorts of hidden properties that can make life easier and—more importantly—more efficient. While we think it’s best to talk about a tool in the chapter where it applies the most (for example, we take a good close look at the Selection tool in Chapter 9, “Making Selections”) some tools can be used in more than one area, and those are the tools we’ll look at here.

Tool shortcuts. The most important productivity tip we’ve found in Photoshop has been the ability to select any tool with a keyboard shortcut. Like other programs in the Adobe Creative Suite, Photoshop tool shortcuts do not use any modifier keys. You press the key alone, without pressing Command, Option, Control, or Alt. Figure 6-13 shows the tool shortcuts.

Some tools in the Tool palette keep multiple related tools undercover. For instance, the Dodge tool also “contains” the Burn and the Sponge tools. The slow way to access the different modes is to press the tool icon to bring up the flyout palette containing the different modes. A faster method is to press the tool’s keyboard shortcut once to select it, and then hold down the Shift key while pressing it again to toggle among the choices. Press M once, and you jump to the Marquee tool; then press Shift-M, and it switches to the elliptical Marquee tool; press Shift-M once more, and it switches back to the rectangular Marquee tool. Note that this shortcut doesn’t cycle through the single-row marquee or the single-column marquee.

Tip

A very efficient way to use Photoshop (or any Adobe Creative Suite software) is the two-handed method: Keep one hand on the mouse or stylus and the other hand over the keyboard, ready to press single-key tool shortcuts. By switching tools using your nonmouse hand on the keyboard, you can keep the mouse over the area you’re editing instead of repeatedly pulling the mouse or stylus over to the Tools palette.

Photoshop lets you change this behavior: If you turn off the Use Shift Key for Tool Switch check box in the General panel of the Preferences dialog—see “Setting Preferences,” later in this chapter—then you don’t have to hold down the Shift key to rotate through the tools; each time you press M, you’ll get a different tool. Conrad prefers to use Shift to cycle through tools, because it ensures that pressing a letter key selects the last tool you used in a tool group. If you cycle without Shift and the Tools palette is hidden, pressing a letter could cycle to another tool in the group that isn’t the tool you thought you were using.

Change a tool’s blend mode. You can change blend modes (Normal, Screen, Multiply, and so on) by pressing Shift-minus sign and Shift-plus sign. If you have a painting tool selected (like the Brush tool), this changes the mode of the selected tool. If you’re using a tool that doesn’t use blend modes, the shortcut escalates to change the mode of the layer itself.

Activate the opposite tool. Some tools have an opposite, kind of like an evil twin except that the opposite tool isn’t evil (perhaps just misunderstood). When you’re using one of these tools, you can get its opposite by pressing Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows). For example, if you’re using the Blur tool, pressing Option/Alt temporarily changes it into the Sharpen tool. The same thing happens with the Dodge and Burn tools.

Options bar shortcuts. The tools on the Tool palette only go so far. You often need to modify the tool’s default settings on the Options bar. Try this: Select a tool, then press Return. The Options bar, even if hidden, appears at this command. Plus, if there is a number-input field on the Options bar, Photoshop selects it for you. When you press Return with the Lasso or Marquee tools selected, for example, the Feather field becomes highlighted on the Options bar.

If there is more than one number-input field on the Options bar, you can press Tab to jump from one to the next. Finally, when you’re finished with your changes, press Return again to exit from the bar and resume work.

You can customize the brushes in Photoshop (see Figure 6-14). It’s important to remember that these brush presets aren’t only for painting with the Brush tool—they also work with any tool that paints, such as the Eraser tool, the Clone Stamp tool, the History Brush tool, and so on. While most of the brush options are designed for fine-art work (simulating charcoal, water colors, and so on), every now and again you may find them helpful in a production environment, too—especially for detailed retouching.

Brush shortcuts. Did you know that the [ and ] keys (the square brackets) increase and decrease the diameter of a brush? Plus, Shift-[ and Shift-] change the brush’s hardness. We now keep one hand on the keyboard and one on our mouse (or tablet pen); when we want to change tools, we press the key for that tool. When we want to change brush size, we cycle through the brushes with the [ and ] keys until we find the size we like. Here’s one more shortcut, too: The Command and period keys move up and down through the brush presets.

Fastest brush selection. Actually, one of the best ways to select a brush is probably via the context menu. On the Mac, hold down the Control key when you click with any of the painting tools and Photoshop displays the Brushes menu wherever you click. In Windows, right-click to see the menu. After selecting a brush size, press Enter or Esc to make the palette disappear.

Hovering pseudoselections. Instead of selecting a brush from the Brushes palette, then painting with it to see how it will really look, hover the cursor over the preset for a moment and Photoshop will display a sample of that brush at the bottom of the palette. If you don’t like it, hover over another brush. When you find one you like, click on it to select it.

Opacity by the numbers. In between changing brush sizes, we’re forever changing brush opacity while painting or retouching. If you’re still moving the sliders around on the Options bar, stop it. Instead, just type a number from 0 to 9. Zero gives you 100 percent opacity, 1 gives you 10 percent, 2 gives you 20 percent, and so on. For finer control, press two number keys in quick succession—for example, pressing 45 gets you 45 percent opacity. If you have a non-painting tool selected in the Tool palette, then typing a number changes the opacity of the layer you’re working on (unless it’s the Background layer, of course). Note that if the Airbrush feature in the Options bar is turned on, then typing numbers affects the Flow percentage rather than the Opacity setting.

Touching up line art. We talk about scanning and converting to line art in Chapter 11, “Essential Image Techniques,” but since we’re on the topic of painting tools, we should discuss the Pencil tool for just a moment. One of the best techniques for retouching line-art (black-and-white) images is the Auto Erase feature on the Options bar. When Auto Erase is turned on, the Pencil tool works like this: If you click on any color other than the foreground color, that pixel—along with all others you touch before lifting the mouse button—is changed to the foreground color (this is the way it works, even with Auto Erase turned off). If you click on the foreground color, however, that pixel—along with all others you encounter—is changed to the background color. This effectively means you don’t have to keep switching the foreground and background colors while you work.

Sampling exactly the right layers. If you’re working on a multilayer image, you may find yourself frustrated with tools like the Smudge, Blur, Magic Wand, or the Clone Stamp tools. That’s because sometimes you want these tools to “see” more layers than just the one you’re working on, and sometimes you do not. Photoshop CS3 expands gives you a choice for each of these tools with the Sample pop-up menu on the Options bar. (Note that in older versions, this was a check box called Use All Layers or Sample Merged.)

When Sample is set to Current Layer, each tool acts as though the other layers weren’t even there. If you choose All Layers, Photoshop samples from the other visible layers (both above and below it) and acts as though they were merged together. A third option, Current and Below, does what it says.

So what good are these new options? One common use is when you want to patch or clone onto a new empty layer, leaving the original layers intact. This is called nondestructive cloning, because if you are unhappy with the results, you can simply erase the patches on the new layer and try again. Without the Sample menu options, you would be able to paint only on the same layer you’re sampling. With the Sample pop-up menu, you can choose Current and Below or All Layers to paint on a blank layer while sampling from other layers that remain intact (see Figure 6-15).

The button next to the Sample pop-up menu is the Ignore Adjustment Layers button, also new to Photoshop CS3 and definitely a worthwhile addition. In previous versions of Photoshop, if you cloned or healed in a document included adjustment layers and you sampled multiple layers, the sample would include the effect of adjustment layers. This was frustrating, because the sample would not match the rest of the layer and the adjustment layer would be applied again to the merged sample. We had to remember to turn off adjustment layers before sampling multiple layers and then turn them back on, and this drove us up the wall. Fortunately, the wonderful new Ignore Adjustment Layers button means that we can now leave adjustment layers on and sample multiple layers perfectly.

If you want your samples or selections to involve only one layer, that’s a situation where you’ll want to choose Current Layer from the Sample pop-up menu.

Photoshop CS3 goes even further in helping you clone effectively, in the form of the new Clone Source palette. We cover the Clone Source palette in Chapter 11, “Essential Image Techniques.”

We almost always scan a little bigger than we need, just in case. So we end up using the Cropping tool a lot. The nice thing about the Cropping tool (as opposed to the Crop feature on the Image menu) is that you can make fine adjustments before agreeing to go through with the paring. Just drag one of the corners or side handles. Here are a couple more ways you can fine-tune the crop.

See what gets cropped. By default, Photoshop darkens the area outside the cropping rectangle so that you can see what’s going to get cropped out before you press Enter. You can adjust this by clicking the Color swatch in the Options bar (when the Cropping tool is selected) and picking a different color from the Color Picker (such as white). You may want to increase the opacity of the color in the Options bar, too. David likes to ghost the cropped-out pixels to near-white, while Conrad likes cropped-out pixels to match the full-screen background color around the image.

Rotating and moving while cropping. You can crop and rotate at the same time with the Crop tool: after dragging out the cropping rectangle with the Crop tool, just place the cursor outside the cropping rectangle and drag to rotate the rectangle. When you press Return or Enter, Photoshop crops and rotates the image to straighten the rectangle. It can be tricky to get exactly the right angle by eye—keep an eye on the Info palette. Also, if the cropping rectangle isn’t in the right place, you can always move it—just place the cursor inside the cropping rectangle and drag.

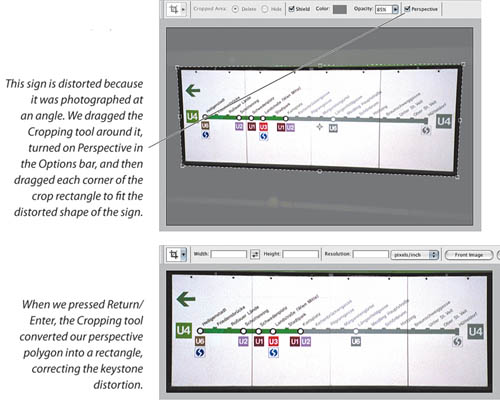

Adjusting for keystone distortion. What do you do about lines in your image that are supposed to be vertical or horizontal, but aren’t? For example, if you take a picture of a painting hanging on a wall, you often need to do so from one side to avoid flash reflections, so the subject ends up being skewed rather than rectangular. Fortunately, our faithful Cropping tool offers a cool option: adjusting for perspective. The key is to turn on the Perspective check box in the Options bar after drawing the cropping rectangle; this lets you grab the corner points and move them where you will.

However, positioning the corner points of the cropping “rectangle” can be tricky. You must first find something in the image that is supposed to be a rectangle and set the corner points on the corners of that shape. In the example of a building, you might choose the corners of a window. Then, hold down the Option and Shift keys (Mac) or Alt and Shift keys (Windows) while dragging one of the corner handles; this expands the crop but retains its shape. When you have the cropping shape the size you want it, drag the center point icon to where the camera was pointing (or where you imagine the center of the focus should be). Then press Enter or Return (see Figure 6-16).

By the way, we find that when we’re using this tool, Photoshop often alerts us that either the center point or the corner points are in the wrong position. This usually happens when you haven’t selected the corner points of something that should be rectangular. In other words, Photoshop acts as a safety net, stopping you when you choose a distortion that isn’t likely to happen in a real photograph. Sometimes simply moving the center point to a different location (by trial and error) does the trick.

For serious distortion corrections, though, you’re better off using the Lens Correction filter, which we discuss in Chapter 10.

Save that layer data. When you crop, you don’t have to lose what’s beyond the newly cropped edges of the document. After you drag a crop rectangle, you’ll see a Hide button on the Options bar. Click that button and after you commit to the crop, the cropped-out pixels will be remembered as big data—material that hangs outside the actual visible image rectangle. Then, if you didn’t get the crop just right, you can either move the image around with the Move tool or re-crop using a different rectangle (see “Expand the Canvas by Cropping,” later in this chapter). Note that this only works on layers other than the Background layer.

Resampling while cropping. Warning: The Cropping tool may be changing your resolution or even resampling your image data without your knowing it! The Height, Width, and Resolution fields in the Options bar (when you have the Cropping tool selected) let you choose a size and resolution for your cropped picture. Basically, these fields save you the step of visiting the Image Size dialog after cropping. But remember that when you use them, they always change your image resolution or resample the image (see Chapter 2, “Image Essentials,” for more on the pros and cons of resampling). That means your image resolution can drop or increase without your realizing it. (In this case, Photoshop is not resampling the data, just adjusting the size of the pixels.) Instead, see the next tip for how to crop to an aspect ratio without altering any other image specs.

If you type a value into the Resolution field, Photoshop resamples the image to that value. This resampling behavior is handy when you want to resample down, but be careful that you don’t ask for more resolution than you really have; resampling up is usually best avoided. (Note that you can only set the Height, Width, and Resolution values before you start cropping; once you draw a cropping rectangle, the Options bar changes.)

Cropping to an aspect ratio. Let’s say you want to crop your image to a 4-by-6 aspect ratio (height-to-width, or vice versa), but you don’t want to resample the image (which adds or removes pixels, causing blurring) or change the image resolution. This is a common requirement in Web design, where pixel-perfect graphics would be ruined by resampling. The Cropping tool can’t perform this task, so you’ll need a different technique. First, select the Marquee (rectangular selection) tool and choose Fixed Aspect Ratio from the Style pop-up menu in the Options bar. The Options bar then lets you type values in the Height and Width fields (here you’d type 4 and 6). Next, marquee the area you want cropped, and then select Crop from the Image menu. See Chapter 9, “Making Selections,” for tips and tricks for the Marquee tool.

Expand the canvas by cropping. Once you’ve created a cropping rectangle with the Cropping tool, you can actually expand the crop past the boundaries of the image (assuming you zoom back until you see the gray area around the image in the document window). Then, after you press Enter, the canvas size actually expands to the edge of the cropping rectangle. This is David’s favorite way to enlarge the canvas.

Tip

To toggle all snap-to options on or off, choose View > Snap. The shortcut is Command-Shift-; (Mac) or Ctrl-Shift-; (Windows).

Cropping near the border. If you’re trying to shave just a sliver of pixels off one side of an image, you’ll find it incredibly annoying that Photoshop snaps the cropping rectangle to the edge of the image whenever you drag close to it. Fortunately, you can temporarily turn off this behavior by unchecking the command View > Snap > Document Bounds. Or, you can hold down the Control key to temporarily disable snapping.

The Eraser tool has gotten a bad rap because people assume you have to use a big, blocky eraser. No, you can erase using any brush—one that’s soft or hard, like an airbrush, or even with the textured brushes in the Brushes palette. And what’s more, you can control the opacity of the Eraser (don’t forget you can just type a number on the keyboard to change the tool’s opacity). This makes the eraser fully usable, in our opinion. However, just because a tool is usable doesn’t mean you have to use it. Whenever possible, we much prefer masking to erasing. The difference? Masks (which we cover in Chapter 8) can “erase” pixels without actually deleting them. Masks just hide the data, and you can always recover it later. Nevertheless, the Eraser tool can, on occasion, get you out of a jam. Here are a few tips:

Erase to History. The Erase to History feature (it’s a check box on the Options bar when you have the Eraser tool selected) lets you use the Eraser tool to replace pixels from an earlier state of the image (see “When Things Go Worng,” later in this chapter, for more on the History feature). Erase to History more or less turns the Eraser into the History Brush tool. For instance, you can open a file, mess with it until it’s a mess, then revert parts of it to the original using the Eraser tool with Erase to History turned on.

The important thing to remember is that you can temporarily turn on the Erase to History feature by holding down the Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) key while using the Eraser tool.

Watch Preserve Transparency when erasing. Note that the Eraser tool (or any other tool, for that matter) won’t change a layer’s transparency when you have the Preserve Transparency check box turned on in the Layers palette. That means it won’t erase pixels away to transparency; rather it just paints in the background color. Don’t forget you can turn Preserve Transparency on and off by pressing / (forward slash).

Erasing to transparency. When you use a soft-edged brush to erase pixels from a layer (rather than the Background layer), the pixels that are partially erased—that is, they’re still somewhat visible, but they have some transparency in them—cannot be brought back to full opacity. For example, if you set the Eraser to 50 percent opacity and erase a bunch of pixels from a layer, there’s no way to get them back to 100 percent again. The reason: You’re not changing the pixel’s color, only the layer’s transparency mask. This isn’t really a tip, it’s just a warning. What you erase sometimes doesn’t really go away.

One of the complaints Adobe heard most in times gone by was that blends in Photoshop resulted in banding. The answer they always gave was to “add noise” to the blend. It’s true; adding noise reduces banding significantly. Fortunately, Photoshop adds noise for us. Of course, you can stop it by turning off the Dither check box in the Options bar, but there’s almost no reason to do so. You may want to turn dithering off if you’re doing scientific imaging or printing to a continuous-tone device that can actually reproduce the gradient without banding.

Adding more noise. If you’re still getting banding even with Dither turned on, you may want to add even more noise to a blend. However, note that you don’t always need to apply the Add Noise filter to the entire gradient; use the filter selectively.

Instead, you might find it better to add noise to only one or two channels. View each channel separately (see Chapter 9, “Making Selections”) to see where the banding is more prevalent. Then add some noise just to the blend area in that channel.

Blends in CMYK. Eric Reinfeld pounded it into our heads one day: If you’re going to make blends in Photoshop images that will end up in CMYK mode, create them in CMYK mode. Sometimes changing modes from RGB to CMYK can give you significant color shifts in blends.

Many custom CMYK profiles produce strange results when you make a blend. In particular, blues tend to have a saturation “hole” and become less saturated when you expect them to become more so. You can often get better results by creating the blend in one of the CMYK working spaces that ship with Photoshop, then assigning your custom profile to the result. The CMYK profiles that come with Photoshop may not represent your exact printing conditions, but they tend to offer much smoother gradients than third-party profiles built with any of the common profiling tools. This is a mildly perverse use of color management, but it works—see Chapter 4, “Color Settings,” for more detail about assigning profiles.

Gradients on layers. Some people make hard work of creating a blend that fades away into transparency. They go through endless convolutions of Layer Masks and Channel Options, or they spend hours building custom gradients, and so on. They’re making it difficult for themselves by not opening their eyes. When you have the Gradient tool selected, the Options bar offers a pop-up menu with various gradient presets in it (see Figure 6-17). By default, these presets include gradients that use transparency. You can create or edit a gradient preset by clicking once on the gradient swatch in the Options bar. You can also select a different set of gradient presets from the pop-out menu to the right of the swatch.

Gradients as a layer. If you harbor even the slightest suspicion that you might need to edit a gradient, and you don’t need anything on a layer except a gradient, think about adding it as a gradient layer, which is a kind of adjustment layer that you can edit at any time. To create a gradient layer, choose Layer > New Fill Layer > Gradient, or click the Create New Fill or Adjustment Layer button at the bottom of the Layers palette and choose Gradient Layer. After you create a gradient layer, you can edit its settings by double-clicking it in the Layers palette—much faster and easier than painting it all over again with the Gradient tool! However, if you’re creating a gradient on a mask, you’ll need to use the Gradient tool.

In Photoshop CS3, the Ruler tool is the tool formerly known as the Measurement tool. Adobe changed the name to avoid confusion with the new Count tool in Photoshop Extended. We still sometimes hear people complain that Photoshop doesn’t have a measuring tool. We think it’s because the Ruler tool hides under the Eyedropper tool by default. The Ruler tool is extremely useful for measuring distances and angles. The keyboard shortcut for this tool is I (or Shift-I if it’s hiding under the Eyedropper tool). Here’s a rundown of how this tool works.

To measure between two pixels, click-and-drag from one point to the other with the Ruler tool.

Once you have a measuring line, you can hide it by selecting any other tool from the Tool palette. To show it again, select the Ruler tool.

You can move the measuring line by dragging the line (not the endpoints). If you drag an endpoint, you just move that end of the line.

You can’t really delete a measuring line, but you can move it outside the boundaries of the image window.

You can turn the measuring line into a V-shaped compass in order to measure an angle by Option-clicking (Mac) or Alt-clicking (Windows) one end of the measuring line and dragging (see Figure 6-18).

Where do you find the measurement? On the Info palette or the Options bar, of course. The palette displays the angle and the horizontal and vertical distances, along with the total distance in whatever measurement system you’ve set up in Units Preferences.

Measuring before rotating. We know you always hold the camera perfectly level, but you may occasionally have to level someone else’s crooked photo or scan. Again, the Ruler tool can help immensely. If you select Arbitrary from the Rotate Canvas submenu (under the Image menu) immediately after using the Ruler tool, Photoshop automatically grabs the angle and places it in the dialog for you.

There are two things to note here. First, the angle in the Rotate Canvas dialog is usually slightly more accurate than the one on the Info palette (within half a degree). Second, if the angle is more than 45 degrees, Photoshop automatically subtracts it from 90 degrees, assuming that you want to rotate it counterclockwise to align with the vertical axis instead of the horizontal axis.

Count tool. The Count tool is new in Photoshop CS3 Extended. It’s grouped with the Ruler, Eyedropper, and Color Sampler tools. It’s intended for the common scientific task of counting objects in an image, such as stars or microbes. The Count tool is out of the scope of this book, so we aren’t giving it much space, but if you do need to count objects, you can simply click the Count tool on each object you want to count in an image, and the tool leaves behind a label with the current count. The Photoshop Help file also includes a procedure for counting objects automatically, if they can be isolated easily using Photoshop selection tools.

While the majority of images touched by Photoshop are edited by a single person, people are increasingly working on pictures in teams. Perhaps the team is a retoucher and a client, or perhaps it’s four Photoshop users, each with specific skills—whatever the case, it’s important for these folks to communicate with each other. Enter the Notes tools (press N). Photoshop has two Notes tools: one for text annotations and one for audio annotations. We suggest using audio annotations to your images only if you’ve never learned to type or if you’re tired of having so much extra space on your hard drive—audio notes can make your files balloon in size (each 10 seconds of audio you add is about 140 K compared to about 1 K for 100 words of text notes).

To add a text annotation, click once on the image with the Notes tool and type what you will. If you type more than can fit in the little box, Photoshop automatically adds a scroll bar on the side. In addition, you can change the note’s color, author, font, and size in the Options bar at any time.

Double-clicking on a note opens it (so you can read or listen to it) or closes it (minimizes it to just the Notes icon). Single-clicking on the Notes icon lets you move it or delete it (just press the Delete key). Or, if you want to delete all the notes in an image, press the Clear All button in the Options bar. Clearing all notes can be useful when you’re creating a final version of an image.

Not just for Photoshop. If you want to send a Photoshop image with annotations to someone who doesn’t have Photoshop, relax. If you choose File > Save As to save the image in Photoshop PDF format, text and audio annotations can be read and heard using Adobe Acrobat or the free Adobe Reader. You can also use Preview in Mac OS X, but you can only read text annotations.

Move the Notes away. By default, Photoshop places your notes windows at the same place in your image as the Notes icon. However, that means the little notes window usually covers up the image so you can’t see what the note refers to. We usually drag the Notes icon off to the side or slightly out into the area that surrounds the picture. Conrad likes to keep notes just visible in the corner of an image because he’s missed notes that were outside the image area; when he doesn’t want to see notes he simply presses Command-H (Mac) or Ctrl-H (Windows), which toggles the View > Extras command. If you can’t see notes in your Photoshop file but you suspect that they’re there, make sure the Annotations item is turned on in the Show submenu (under the View menu). When this is off, no Notes icons appear.

Each tool in the Tool palette offers one or more options, such as the size of a brush’s diameter, or whether a selection is feathered, or what mode a tool will paint in (Multiply, Screen, and so on). It’s a hassle to remember to set all the tool options, especially if you need to change them frequently. Fortunately, Photoshop can remember multiple tool settings for you if you use the Tool Presets feature.

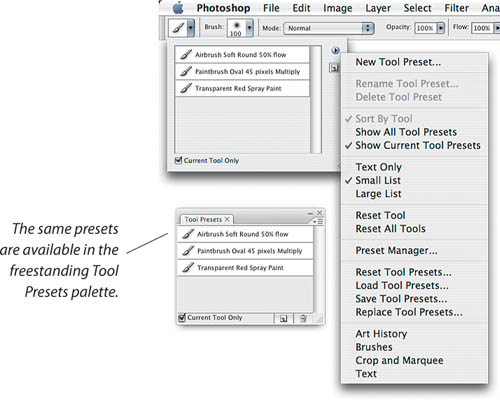

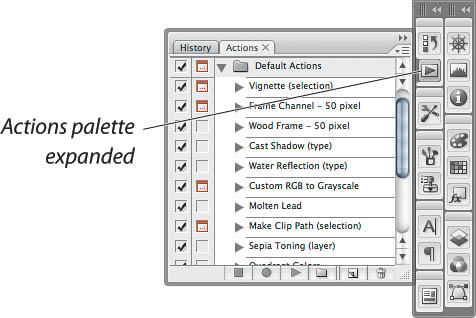

The Tool Presets feature lives in two places: at the far left side of the Options bar, and in the Tool Presets palette (choose Window > Tool Presets). We find that the palette is most useful for fine artists who need to switch among various tool presets, often within the same image (see Figure 6-19). Production folks like us tend to keep the palette closed and select tools from the Tool Presets pop-up menu in the Options bar. One of the reasons that tool presets live on the Options bar is that a tool preset includes the settings you’ve made in the Options bar.

To create a new tool preset, select any tool in the Tool palette, change the Options bar to the way you want it, click on the Tool Presets pop-up menu in the Options bar, then click the New Tool Preset button (it looks like a little page with a dog-eared corner). Or, even faster, after setting up the tool, you can Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) the Tool Presets icon in the Options bar. When Photoshop asks you for a name, we suggest giving the tool preset a descriptive name, like “ShapeTool Circle 50c20m.”

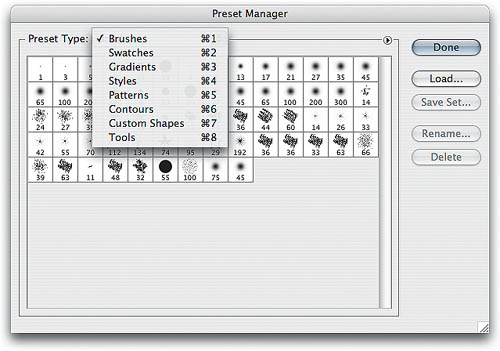

Photoshop also comes with several premade collections of tool presets, such as Art History and Brushes. The trick to finding these (and doing all sorts of other things with tool presets, like saving your own sets), is to open the Preset Manager dialog (see Figure 6-20) by choosing Preset Manager from the Tools palette menu; the same menu is available in the top right corner of the Tool Presets pop-up menu from the Options bar.

Unfortunately, there’s no way to edit a tool preset once you make it—you can only create a new one and delete the old one by choosing Delete Tool Preset from the Tool Preset menu.

To reset the tool options for either a single tool or for all the tools, Control-click (Mac) or right-click (Windows) on the Tool Presets icon on the Options bar.

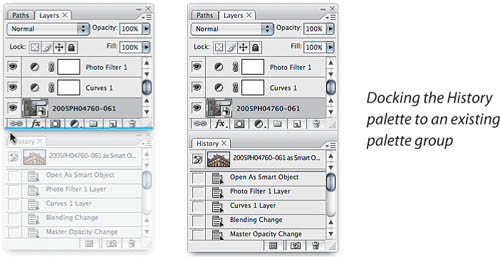

There’s little doubt that palettes are both incredibly useful when you need them and incredibly annoying when they’re in your way. You don’t have to accept how the palettes are arranged by default. The most important tip is that you can regroup palettes by dragging a palette tab to another palette tab, or stack them by dragging a palette tab to the bottom of another palette. Photoshop CS3 extends the traditional grouping and stacking behavior with palette docks that stick to the left and right sides of the monitor.

The new palette docks and workspaces in Photoshop CS3 change the rules a bit. If you think you’re pretty familiar with palettes in Photoshop, you may be able to skip most of this section, but you’ll still want to read the all-new Workspace tips.

In the past, workspaces were simply a way to save palette arrangements, keyboard shortcuts, and custom menu sets for quick and easy recall. In Photoshop CS3, workspaces gain a new set of features that help you work with large collections of palettes in faster, more space-efficient, and less obtrusive ways.

Tip

If you or one of your “friends” has hopelessly scrambled your shortcuts, menus, or workspace beyond recognition, just reset your settings. On the Window > Workspace submenu, you’ll find the commands Reset Palette Locations, Reset Keyboard Shortcuts, and Reset Default Workspace.

To save a workspace, set up the palettes the way you want them, optionally load any custom keyboard shortcut and menu sets, and choose Window > Workspace > Save Workspace. Saved workspaces appear on a Workspace pop-up menu on the Options bar, as well as at the bottom of the Workspace submenu, below the workspaces that come with Photoshop. For even easier recall, use the Keyboard Shortcuts and Menus dialog to assign keyboard shortcuts to your favorite workspace menu commands.

New workspace features. Photoshop CS3 introduces the same turbocharged workspaces that now appear in the rest of the Adobe Creative Suite 3 applications: You can create vertical stacks of grouped palettes and dock them to the edge of the screen, collapse palettes into labeled or unlabeled icons to save space, and automatically expand and collapse the docked stacks to maximize your screen space.

If a palette group has a light gray top bar, it’s free-floating. If it has a dark gray top bar, it’s docked to the side of the monitor or to another palette stack (see Figure 6-21). As always, you can drag a palette tab to dock it with others or tear off a palette dock so that it’s free-floating.

To expand or collapse a stack, click the dark gray bar at the top of a stack (see Figure 6-22). If the bar is very narrow, you can click the light gray double triangle icon at the right edge of the dark gray bar; it does the same thing.

To make a stack narrower or wider, drag the vertical ribs at the left side of a dark gray top bar. You can set the width of both the collapsed and expanded state of a stack. A collapsed stack can be as narrow as a vertical stack of unlabeled icons (see Figure 6-22), or if you’re still learning what the icons represent, you can widen a collapsed stack to reveal the labels. If you need to free up as much space as possible while still keeping a stack visible, we recommend collapsing palettes all the way down to the icons—remember, you can still see an icon title by holding the mouse over an icon until its tool tip appears.

You can dock a palette to either side of the screen or to another palette stack; just drag a palette tab to either side of the screen until a blue line appears at a dockable location (either the screen edge or the edge of already docked palettes). We find that having multiple stacks against the side of the screen starts to make sense on high-resolution, widescreen monitors, where there’s actually room to spread out horizontally. If you have room to leave frequently used palettes open, you don’t have to repeatedly expand and collapse palettes.

You can dock palettes only to the sides of your main monitor, not to the top or bottom. You can’t dock stacks at all on any other connected monitor. However, you can keep free-floating palettes on another monitor and group them however you like. In other words, if you prefer to keep your palettes on a second monitor, like we do, you can continue to do that in Photoshop CS3.

When you click a collapsed icon to pop open a palette (see Figure 6-23), by default the palette stays open until you click its icon again or click another palette. However, when palettes stay open, they tend to intrude upon the image area. If you’d prefer that an expanded palette puts itself away, open the Preferences dialog, click the Interface panel, and then click Auto-Collapse Icon Palettes.

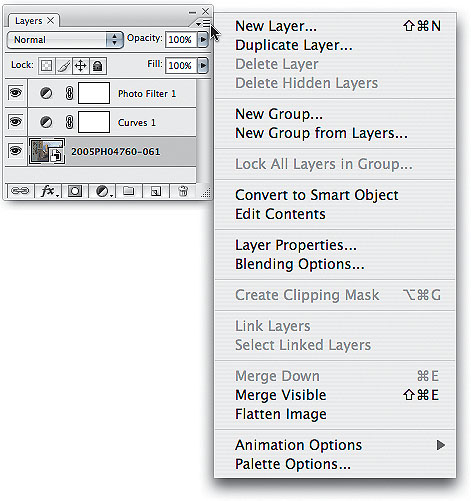

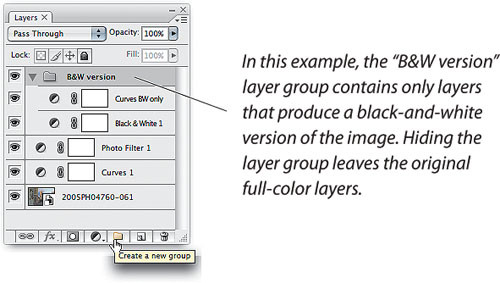

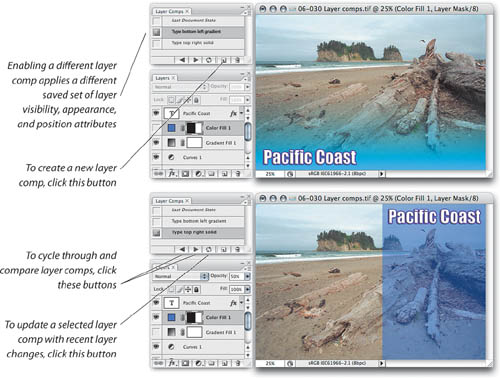

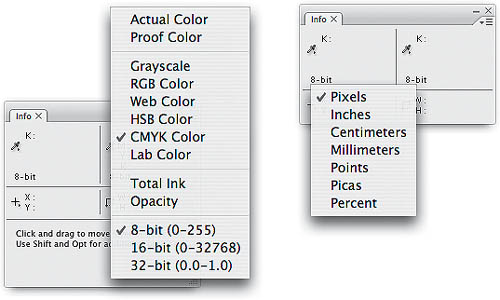

We think workspaces are extremely useful, because there is no one right way to arrange things. When Conrad connects his laptop to a color-calibrated desktop monitor, he likes to use the higher-quality desktop monitor as the main image viewing area and place as many palettes as possible on the laptop monitor. When he uses the laptop by itself, there isn’t nearly enough room to replicate the two-monitor desktop arrangement, so he becomes picky about which palettes are visible. To switch instantly between the two palette arrangements, Conrad saved each arrangement as its own workspace.