In the previous edition of this book, we said it was only a matter of when, not if, digital would replace film for most applications. Now we look back on that statement and laugh, because in the short time between these editions, the transition from film to digital has largely become complete. In addition, photographers have latched onto the idea of processing files of raw data straight from the camera’s sensor because it provides a level of control and potential quality comparable to developing and printing your own film.

That said, anyone who has made the switch from film to digital can tell you that the time savings of digital photography (compared to film) is often offset by new tasks that photographers didn’t have to worry about before. Having total control over the processing of every image means a photographer must now set aside the time and acquire the skills to do it right, instead of sending film to the lab and getting something else done while waiting for the lab to develop or print it. Digital storage is so cheap and capacious that a typical shoot now produces far more frames than it would have using film. But that also means there are that many more frames to cull and process afterward, burdening a photographer further.

The good news is that Adobe Photoshop CS3 benefits from what everyone learned from earlier stages in the transition to serious digital photography. Photoshop CS3, along with the Adobe Bridge and Adobe Camera Raw software included with it, can fulfill the key tasks of a high-volume digital camera workflow from beginning to end—something that wasn’t possible in previous versions. Also, Adobe has added so many useful features to Adobe Camera Raw 4.x that in some cases, you may not even need to open the images in Photoshop.

We assume that you’re not interested in spending any more time than you have to on each image, so we’ve set up this chapter with that idea as the guiding principle. This chapter is about how to get through Adobe Camera Raw in the fewest number of moves, and we’ll also talk about processing large numbers of images as quickly as possible. If your photography is more about spending the bulk of your time on a few important images, concentrate on the sections about culling images in Bridge and working in Camera Raw. But before we get into strategies for these workflows, let’s look at digital raw capture.

Camera Raw appears as a file format in the Open dialog in Photoshop, but it isn’t actually a single file format. Rather, it’s a catchall name for camera files that consist of unprocessed data straight from the camera’s sensor. One of the reasons they’re called raw files is that they haven’t even been processed into the RGB color of more common camera formats such as JPEG. Each camera produces its own flavor of raw data, so Camera Raw and its competitors usually need to be updated for the raw formats of new cameras.

A list of officially supported cameras appears on Adobe’s Web site. As we write this, the URL is www.adobe.com/products/photoshop/cameraraw.html. Cameras that are not on the list sometimes work anyway; this is called unofficial support and it sometimes means the software company is still testing the camera. Adobe wisely doesn’t officially support a new camera until it has thoroughly tested a final, shipping version of the camera. If you want to buy a new camera that shoots in raw format, check Adobe’s list to see if it’s supported yet; if it isn’t, have patience. Chances are that the raw format of any significant new camera will be supported in the next release of Camera Raw, which is updated about four times a year.

Digital still cameras use color filters over each sensor in the area array to split the incoming light into its red, green, and blue components. Each sensor captures only one color, depending on which filter that covers it. The actual capture is essentially a file that records the amount of light recorded by each element in the array.

Considerable processing is required to turn this raw capture into an RGB color image—so much in fact, that today’s on-the-fly raw processing would not have been practical on the computers available just a few years ago. When your camera is set up to save JPEG files (that’s the default for most digital cameras), the conversion is performed by the camera’s firmware, using the on-camera settings for white balance, tone, saturation, sharpness, and so on. However, when you tell your camera to save images in its raw format, the processing is deferred until you open the image on the computer using specialized software (like Camera Raw).

Shooting raw images is much more flexible than shooting JPEG. When you shoot raw, the only on-camera settings that permanently affect your capture are the shutter speed, aperture value, ISO value, and focus. All other settings—white balance, tone curve, color space, contrast, saturation—are written into the capture as metadata (literally, data about data) that accompanies the raw information. Camera Raw may use this metadata as guidance in processing the capture into an RGB image, but the settings have no effect on the actual capture of the image pixels.

Raw captures allow tremendous flexibility in postprocessing, letting you reinterpret white balance and exposure with no degradation to the image. Rather than stretching or squeezing levels, you’re simply reinterpreting the way the captured photons get converted into an RGB image.

Raw capture offers other key benefits:

It creates a smaller file on disk than an uncompressed RGB image.

It allows you to capture a high-bit image from a one-shot camera.

It allows you to convert the image into RGB spaces other than the ones supported by the camera.

There are several disadvantages to using/shooting raw, too. Of course, the primary one is that you need to process the images, which takes time. But raw files are also larger than JPEG images, so it may take longer to save them to your camera’s storage medium (which will fill faster, too). However, we’ve struggled with most of the software that converts raw files, and we’re convinced that Camera Raw is one of the fastest available—fast enough to make shooting raw worthwhile for all but the most time-critical applications.

Moreover, Camera Raw starts working for you automatically as soon as you point Bridge at a new folder of raw images, quickly generating thumbnails and previews so you can see the raw images in enough detail to make an initial choice between the “hero” shots you plan to keep and the less successful efforts you plan to discard (or revisit later).

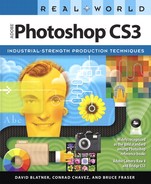

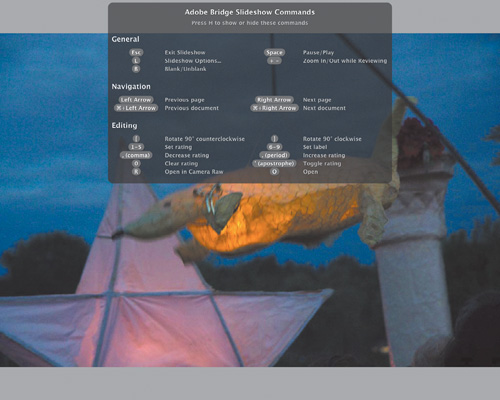

If you want to simply jump in with both feet, take a quick look at Figure 5-1, then get to work. But the combination of Bridge and Camera Raw is complex enough that you’ll probably want to read the rest of this chapter to get the rest of the juicy details! (There is even an entire book on the subject: Real World Camera Raw with Adobe Photoshop CS3—which expands on many of the ideas in this chapter.)

We’ve spent most of this chapter looking at the various tools offered by Bridge and Camera Raw. But knowing what buttons to push to get the desired result just means you know how to do the work. To turn that understanding into a practical workflow, you need to understand and optimize each part of the process.

There are four basic stages in a raw workflow. You may revisit some of them—going back and looking at the initial rejects, or processing the images to different kinds of output file—but everything you do will fall into one of four stages.

Copying files from the camera. You start by copying the raw images to at least one hard disk.

Verifying images. You point Bridge at the newly copied images and let it cache the thumbnails, previews, and metadata.

Preproduction. You work with the images in Bridge, selecting, sorting, applying metadata, and editing with Camera Raw.

Production. You process the raw images to output files.

In the remainder of this chapter, we’ll look at each of these four stages, but our emphasis lies in the preproduction stage—the work you do in Bridge and Camera Raw—because most of the actual work happens in this stage.

There are likely as many workflows are there are photographers—maybe more! One of the wonderful things about Bridge, Camera Raw 4.x, and Photoshop CS3 is the incredible workflow flexibility that they offer. The price of this flexibility is, of course, complexity. There are multiple ways to accomplish most tasks, and it may not be obvious at first glance which way is optimal in a given situation. Understanding the different ways of accomplishing the basic tasks is the tactical level. But to make a workflow, you also need a strategy that tells you how and when to employ those tactics.

Even a single photographer may need more than one workflow. On the one hand, there’s the workflow you need when you’re on a shoot, the client is looking over your shoulder, and you need to agree on the hero shots before you strike the lighting and move on. On the other hand, there’s the workflow you’d like to follow when you’re reviewing personal work with no deadlines attached. Between these extremes are many points on the continuum.

We can’t build your workflow for you, so we’ll offer two key principles of workflow efficiency that should always guide you.

Do things once, early, and efficiently.

Do things automatically whenever possible.

Be methodical.

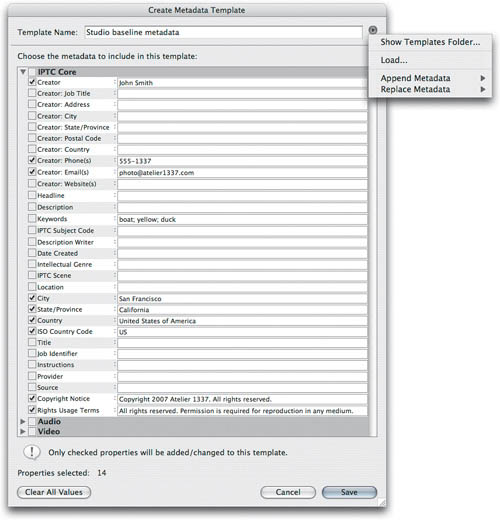

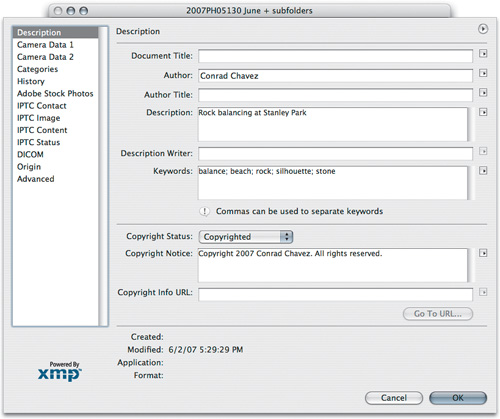

When you apply metadata such as copyright, rights management, and keyword to your raw file, the metadata is automatically carried through to all the TIFFs, JPEGs, or PSDs that you derive from that raw file.

By the same token, if you exploit the power of Camera Raw to its fullest, many of your images may need little or no postconversion work in Photoshop, so applying Camera Raw edits to your images is likewise something that can often be done only once.

A key strategy that helps you do things once is: Start with the general and proceed to the specific. Start with the things that can be done to the greatest number of images, then make increasingly more detailed treatments of ever-decreasing numbers of images, reserving the full treatment—careful hand-editing in Camera Raw and Photoshop, applying image-specific keywords, and so on—to those images that truly deserve the attention.

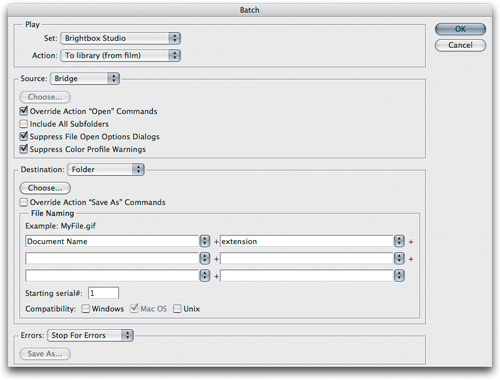

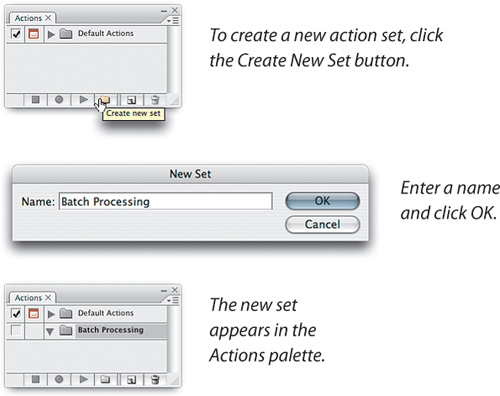

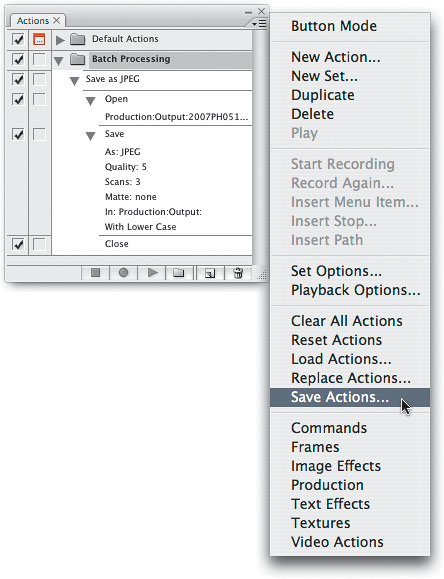

Automation is a vital survival tool for more easily dealing with the volumes of data a raw workflow entails. Once you’ve told a computer how to do something, it can do that something over and over again. Photoshop actions are obvious automation features, but metadata templates and Camera Raw presets are important automations, too.

We rarely open a single image from Camera Raw directly in Photoshop unless we’re stacking multiple renderings of the raw file into the same Photoshop image.

In the vast majority of cases, we convert our raw images using either Batch or Image Processor commands on the Tools > Photoshop submenu in Bridge. Upon opening any images—raw or otherwise—in Photoshop, we often use actions to create adjustment layers so that the images are immediately ready for editing.

Once you’ve found a rhythm that works for you, stick to it. Being methodical in this way makes mistakes less likely and allows you to focus on the important image decisions that only you can make.

For better or worse, computers always do exactly what you tell them to, even if that’s jumping off a cliff. Established routines (and Actions) help ensure that you’re telling the computer to do what you really want it to.

The first thing you’ve got to do is get your images off the camera and into your computer. There are two parts to this: The hardware you use to connect the computer to the camera, and the software you use to transfer the images from the camera to your computer.

Hardware. You can use the cable that came with the camera, but using a card reader is generally faster and more efficient, as we explain below.

Software. After the computer sees the card, you can use any software that transfers the images to your hard disk. The simplest way is to mount the card as a volume on the desktop and drag the images from there to a folder on your hard disk. We recommend using software designed to copy images from a camera, such as the Adobe Photo Downloader, because camera-download utilities provide an opportunity to automate several important tasks as the images are copied. We talk more about this in “Using Adobe Photo Downloader” below.

Best practices. Transferring your images from the camera to the computer is one of the most critical, yet often one of the least examined, stages of your workflow. It’s critical because at this stage, your images exist only on the camera media. Compact Flash, Secure Digital, and microdrives aren’t dramatically more fragile than other storage media, but at this stage, there’s only one copy! Losing previews or camera raw settings is irritating, but you can redo the work. If you make mistakes while you copy images to your computer, you can lose images.

Tip

Image files on a memory card can be corrupted by something as simple as pulling the card out of the reader without first ejecting it in the software. If you think you’ve lost images on a card, do not format it! Doing so will permanently delete any recoverable data on the card. Cards from major vendors often include data-recovery software such as PhotoRescue—turn to that software first. If that fails, and the data is truly irreplaceable, several companies offer data recovery from memory cards, usually at a fairly hefty price.

The following ground rules have thus far prevented us from losing even a single image.

Don’t use the camera as a card reader. Most cameras will let you connect them to the computer and download your images, but that’s a bad idea for at least three reasons: Cameras are very slow as card readers, when the camera is acting as card reader, you can’t shoot with it, and you’re draining the camera’s battery.

Never open images directly from the camera media. It’s been formatted with the expectation that the only thing that will write to it is the camera. If something else writes to it, maybe nothing will happen, but then again, maybe something bad will.

Don’t rely on just one copy of the images. Always copy them to two separate drives before you start working.

Don’t erase your images from the camera media until you’ve verified the copies. See “Verifying Images,” later in this chapter.

Always format the cards in the camera in which they will be shot. Formatting camera cards with a computer is not reliable.

Following these rules takes a little additional time up front, but much less time than a reshoot would (if reshooting is even a possibility).

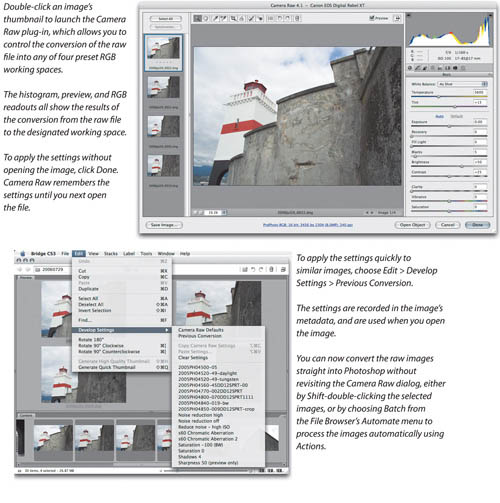

With Photoshop CS2, you had to copy images to your computer by manually dragging and dropping them from the card to a folder on your computer. If you wanted to automate the process, you had to find a camera-download utility. Fortunately, Photoshop CS3 comes with the Adobe Photo Downloader utility, which simplifies and automates downloading. Among other things, it can:

Set a folder on your hard disk as a destination for images being copied from the card.

Tip

If the wrong program launches when you plug in a camera or card, make sure that the program you want to use (such as Adobe Photo Downloader) is set as the default downloader, and check other photo downloaders on your machine (such as Adobe Lightroom or Apple Image Capture) and make sure they’re not set to be the default downloader. In most cases, download behavior is set in a program’s preferences.

Rename images to your standard as you import them.

Make a backup copy of the images in a different folder.

Apply a metadata template to all incoming images (we talk about this later, in “Applying Keywords and Metadata”). For example, you can add a copyright notice to every image as it’s imported.

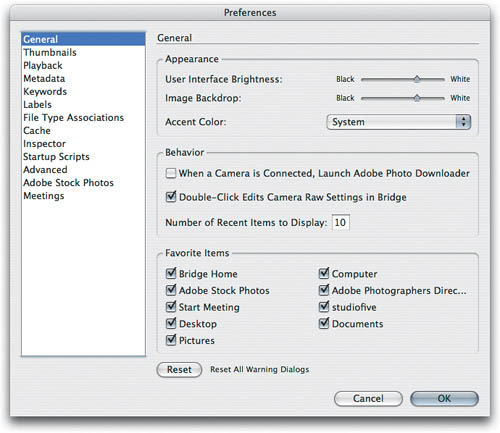

Opening Adobe Photo Downloader. You won’t find Adobe Photo Downloader as a stand-alone application—you launch it from Adobe Bridge. To open Adobe Photo Downloader, start Adobe Bridge and then choose File > Get Photos from Camera. If an alert appears asking you if you want Adobe Photo Downloader to launch whenever you connect a camera or card, you can click No until you make a final decision as to whether you prefer Adobe Photo Downloader to other methods. When you do make a final decision, the next time that alert appears, you can click Don’t Show Again so it won’t come up every time you start the utility.

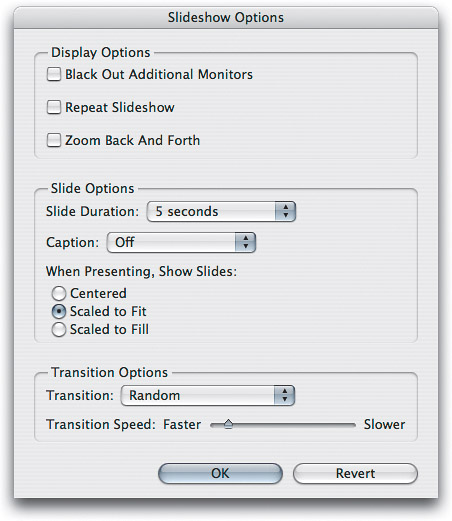

Dialog Views. You can display the Photo Downloader window as a Standard dialog or Advanced dialog (see Figure 5-2). The Standard Dialog contains most of the features, but we prefer the Advanced Dialog because you can do a few more very useful things: See previews of the images you’re about to copy, deselect any images you don’t want to copy, and apply a metadata template to all incoming images.

Copying images is something you don’t want to do more than once, so take a little time to get it right the first time. When you’re done setting the following options, click Get Photos to start copying images.

Previews, source, and image selection. In the Advanced Dialog, check the previews to see if you’re downloading what you want. If the previews don’t look right, make sure the Source pop-up menu is set correctly, in case there are multiple cameras or cards plugged in to the computer.

If you don’t want to download an image, deselect its check box. To change this option for multiple images at once, Command-click (Mac) or Ctrl-click (Windows) the images you want to change (they’ll become selected, indicated by blue borders), and then change the check box for any selected image. The Check All and UnCheck All buttons at the bottom of the Advanced dialog are shortcuts for changing the check boxes.

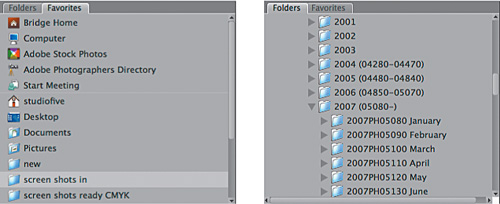

Save Options. The location is the folder where the images will be copied; click the Choose button to change the folder. If you want Photo Downloader to automatically create subfolders for your shoots, choose a folder-naming option from the Create Subfolder(s) pop-up menu.

Tip

Add your Location folder as a Favorite in Bridge or on your desktop, so that you can always get to it in one click.

To have Photo Downloader automatically rename images as they’re copied, choose a renaming option from the Rename Files pop-up menu. In addition to the date-based naming options, the Same As Subfolder option bases the filenames on the name of their subfolder.

The “Preserve Current Filename in XMP” option only applies if you rename a file. It keeps the original filename in the image’s XMP metadata, and you can view this information in Bridge.

Advanced Options. We recommend checking the Open Adobe Bridge check box, because if it’s on, as soon as the images are copied, Adobe Bridge opens to that folder, so that you can work with your images right away.

We also like to check the Convert to DNG option, because the DNG (Digital Negative) format packages raw sensor data in one convenient, vendor-independent file, without storing the metadata in separate “sidecar” files that you have to track along with the raw file. For information about the options you find when you click the Settings button, see “The Main Control Buttons” later in this chapter.

The Save Copies To check box creates a second copy of each image in the folder you specify. The best way to use the Save Copies To check box is to set the folder to a completely different hard disk. This may all seem paranoid, but professional photographers require this level of backup in case something goes horribly wrong, often using a small portable drive as their backup. For example, if a photojournalist copies photos from a card to a laptop, then erases the card so that he or she can take more photos, and then the laptop’s hard disk dies (and you know that happens), the only existing images of a one-time event may be gone forever.

Apply Metadata. If you’ve set up metadata templates in advance, you can choose one from the Template to Use pop-up menu. We recommend that you create and apply a template that at least adds your name and copyright information to all images you shoot. For more information about setting these up, see “Using Metadata Templates” later in this chapter.

We recommend that you carefully consider your Photo Downloader settings in the context of how you want your overall photo collection to be organized. If you work out folder and file-naming conventions and your standard metadata in advance, your photo collection will automatically build itself in an organized fashion. If you just copy images without taking advantage of the automatic organizational options available in today’s downloading utilities, you’ll have a growing pile of images to rename, annotate, and organize later, and take it from us, that isn’t any fun to deal with.

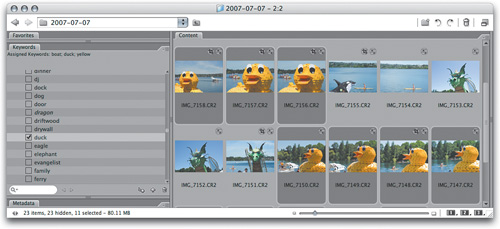

Once you’ve copied the raw files to your hard disk, the next thing to do is to point Adobe Bridge at the folder containing the raw images. (If you checked the Open Adobe Bridge option in Photo Downloader, this should happen automatically.) If you haven’t opened Adobe Bridge yet, it’s in the Adobe Bridge CS3 folder, inside the Applications folder (Mac) or Program Files folder (Windows).

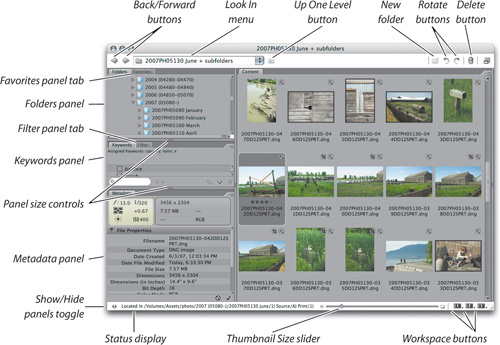

Bridge is command central for dealing with hundreds of images. You’ll use it to make your initial selects, to apply and edit metadata including Camera Raw settings, and to control the processing of the raw images into a deliverable form.

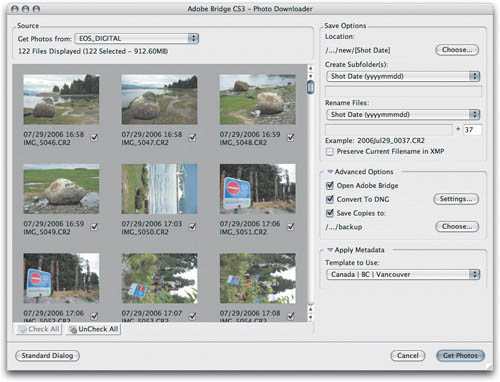

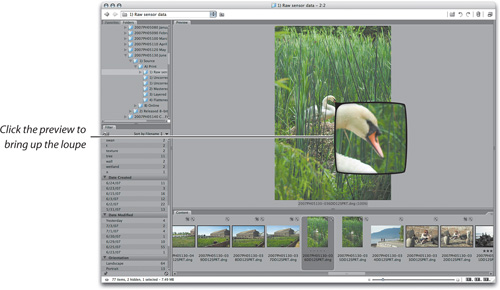

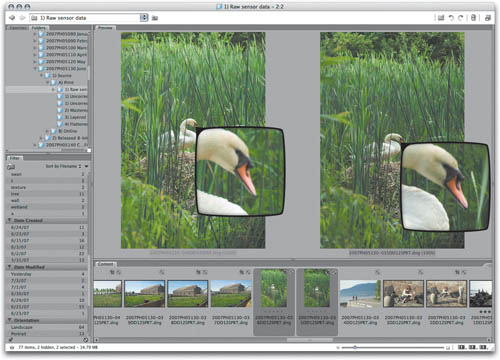

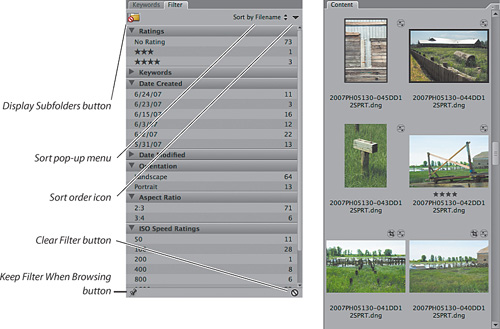

But before you start doing any of these things, give Bridge a few minutes to generate the thumbnails (see Figure 5-3) and previews and to read the image metadata. It’s a good idea to let it finish building the cache for the folder before starting work.

Tip

Professional photographers use the term “selects” (as a noun) to describe the best images from a shoot. If you also use Adobe Lightroom, you’ll notice that it calls selects Picks.

The reason is simple. While you can identify and open raw images as soon as the thumbnail appears, the thumbnails are generated by the camera and Bridge simply displays them. To build the high-quality previews, though, Camera Raw has to actually read the raw data. A good way to inspect the high-quality previews in detail is with the loupe; see “Evaluating and Comparing” later in this chapter.

If there’s a problem reading the images, the problem will only show up on the high-quality thumbnail and preview. The initial thumbnails are the camera-generated ones, and they don’t indicate that the raw file has been read successfully. The high-quality ones do indicate that the raw file has been read successfully, so wait until you see them before you erase the raw image files from the camera media.

If you see a problem at this stage, check the second copy (if you made one) or go back to the camera media if you haven’t erased the card already. It’s fairly rare for the data to get corrupted in the camera (though it does sometimes happen, particularly in burst-mode shooting), so the first suspect should be the card reader.

When you want to turn raw camera files into usable images, Adobe Camera Raw is your friend. Like the Photo Downloader, Camera Raw isn’t stand-alone software; it’s plug-in software that you can use only from within Photoshop or Bridge.

Camera Raw can be the first stage of your digital workflow if you use it to prepare images that you intend to send to Photoshop for more precise editing. However, the controls in Camera Raw are quite capable—so much so that many images may not need to be sent to Photoshop. While Camera Raw can’t print, it does have the ability to generate DNG, JPEG, TIFF, and Photoshop files on its own. If you use Camera Raw this way, it can be the last stage in your digital workflow.

There may be times when you want to work in Camera Raw but you don’t need to pass the images to Photoshop just yet. That’s why you can also open Camera Raw from Bridge. In Bridge, you can run Camera Raw without having to open Photoshop, which can free up RAM on your computer for other things.

Tip

If you try to open many images in Camera Raw but your available RAM is limited, Camera Raw may display an alert telling you that you’re opening too many images at the same time. If you don’t want to open fewer images, first make sure you don’t have unnecessary applications running, and then make sure you’re launching Camera Raw from Bridge instead of from Photoshop. Bridge needs less RAM to operate than Photoshop, so Camera Raw can open more files at once from Bridge than it can from Photoshop.

The ability to open Camera Raw in either Photoshop or Bridge may seem incidental, but there are practical advantages. For example, if you want to edit the Camera Raw settings for one or more images but don’t plan on opening them in Photoshop, you can open Camera Raw in Bridge while Photoshop is busy (such as when it’s running a batch process). Or you could edit an image in Camera Raw in Photoshop while Bridge is busy caching a folder full of images. You can even open one Camera Raw window in Bridge and another in Photoshop, though doing so can make you one very confused puppy!

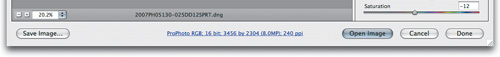

The subtle clue as to which application is currently hosting Camera Raw appears in one button: When Camera Raw is hosted by Bridge, the default button is labeled Done (clicking it closes Camera Raw, applies the settings to the raw file, and returns you to Bridge). When in Photoshop, the button is labeled Open (clicking it closes Camera Raw, applies the settings to the raw file, and opens the converted image in Photoshop).

If you already know which shots you want to open in Camera Raw, you can skip this section and go on to the next one. However, there’s another option if you usually shoot more than one frame of each subject to ensure that you get the right shot: After you copy images to your hard disk, use Bridge to narrow down your shoot, selecting only the best images to open and edit in Camera Raw and Photoshop. Doing this has several benefits:

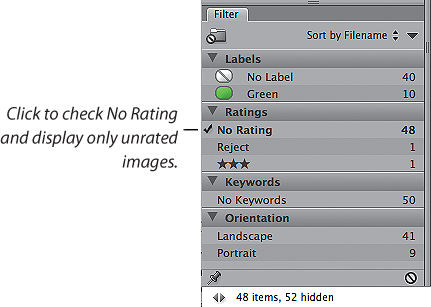

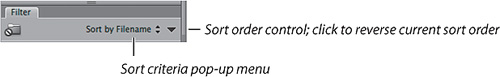

You can rate images to prioritize them. You can also mark images as rejected so that you can delete them, freeing up disk space.

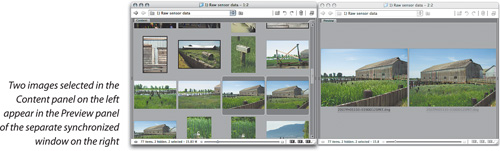

You can compare multiple images and use a loupe to compare images in detail.

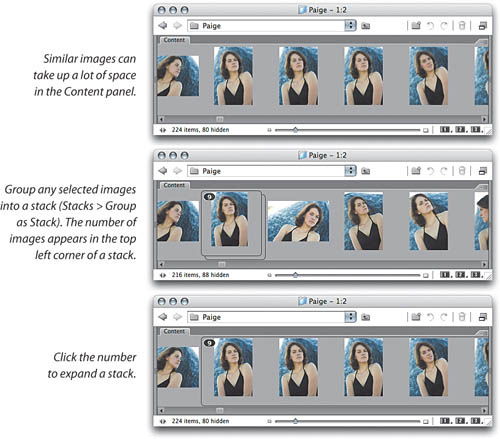

You can stack images to keep related images together.

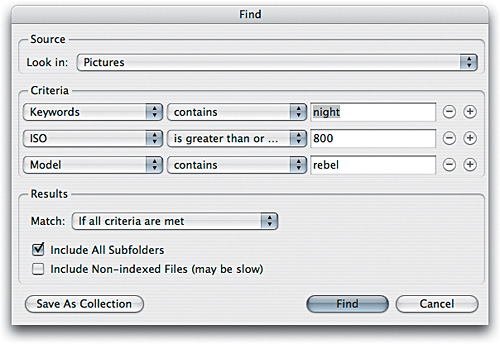

You can filter your images to display only images that contain specific metadata, such as a keyword.

If you need to narrow down your shoot before going into Camera Raw, you should read about the above Bridge features above in detail before you start working in Camera Raw. See “The Preproduction Phase” later in this chapter.

You can open a supported file with Camera Raw in several ways:

In Photoshop, choose File > Open, select one or more raw files, and click Open.

In Bridge, or on your desktop, select at least one raw file and double-click it.

In Bridge, you can also open a selected, supported file in Camera Raw by pressing Return.

Opening the file from your desktop works as long as Photoshop is the application that is set to open your camera’s raw files; if the file icon has an Adobe icon with a “CRW” badge, you should be able to double-click it. A raw file opened in Photoshop automatically opens in Camera Raw.

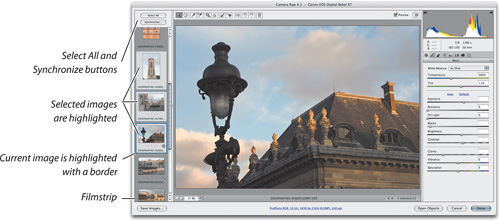

If you open multiple files in Camera Raw, you’ll see the filmstrip which lets you select which images are affected by the settings you change, along the left side of the dialog. You can also use the Synchronize button to spread settings from one image to others inside Camera Raw (see “Filmstrip Mode,” later in this chapter).

Tip

Camera Raw is now so packed with features that it deserves its own book. Fortunately, such a book does exist. To gain a complete understanding of Camera Raw, pick up a copy of Real World Camera Raw with Adobe Photoshop CS3 by Bruce Fraser and Jeff Schewe, by the very same Adobe Press that brought you this book.

Turn off default autocorrection. Camera Raw autocorrects images by default. Some people seem to love this feature, while others hate it because it tries to “correct” your manual exposure settings, like bracketing. Fortunately, the behavior is easily changed: Open Camera Raw preferences and turn off the check box for Apply Auto Tone Adjustments and click OK, make sure that White Balance is set to As Shot, then choose Save New Camera Raw Defaults from the Camera Raw menu. Note that the defaults are per camera model, so you’ll need to do this for each camera model you use. You can still apply autocorrection to an individual image by clicking Auto, or by pressing Command-U in Mac OS X or Ctrl-U in Windows. See “Using Auto Tone Adjustments,” later in this chapter, for more details.

One of the biggest changes to Camera Raw in Photoshop CS3 is that you can now open TIFF and JPEG images in Camera Raw and lets you use Camera Raw features on them. This doesn’t magically bring the inherent qualities of raw files to TIFF and JPEG files, however; it just makes some tasks easier. For example, it can sometimes be easier to get rid of a color cast using the White Balance control in Camera Raw rather than playing with the various color-correction features in Photoshop. Another powerful advantage is that you can now use Camera Raw and Bridge batch-processing features on TIFF and JPEG files, such as the ability to synchronize nondestructive Camera Raw adjustments instantly across multiple images. This means that even photographers who shoot in JPEG can take advantage of the Camera Raw workflow, even if the images themselves are not as flexible as raw files.

By default, TIFF and JPEG images open in Photoshop. To open a TIFF or JPEG image in Camera Raw, Control-click (Mac) or right-click (Windows) an image and choose Open in Camera Raw from the context menu. In Photoshop, you can choose File > Open, select a TIFF or JPEG image, change the Format pop-up menu to Camera Raw, and then click Open, although you can open only one file at a time this way.

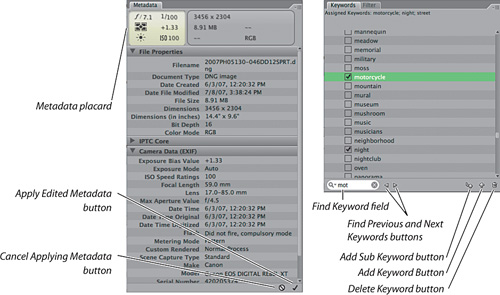

The Camera Raw dialog offers two sets of controls; one static set that is “sticky” (the settings remain unchanged until you change them) and another that is dynamic, and image-specific. The later set changes depending on which tab is currently selected (see Figure 5-4).

The static controls fall into several groups: the toolbar, including the preview controls; the histogram; the Camera Raw menu, and the main control buttons. Let’s look at each of these.

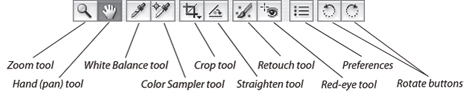

The Camera Raw toolbar (see Figure 5-5) contains eleven buttons, including two new tools and a new button that opens the Preferences dialog.

Edits in Camera Raw never change the pixels in the original files. Whether you edit raw, TIFF, or JPEG files, Camera Raw stores its changes as metadata, only applying the changes to files you export from Camera Raw or open in Photoshop. The changes are stored in the file if Camera Raw can write to the file’s metadata (DNG, TIFF, and JPEG files). If that’s not possible, the changes are stored in an XMP metadata sidecar file with the same base name as the raw file.

Zoom and pan. The zoom (magnifying glass) and pan (grabber hand) tools work just like their Photoshop counterparts.

White balance. The White Balance tool (press I) lets you set the white balance by clicking on the image. Unlike the white Eyedropper in Levels or Curves, it doesn’t allow you to choose a source color, and it doesn’t affect the luminance of the image. Instead, it lets you set the white balance—the color temperature and tint—for the capture by clicking on pixels you think should be neutral.

Tip

The White-balance tool in Camera Raw works best on a light gray that’s close to diffuse highlight, but one that still contains detail, rather than on a specular highlight that’s pure white. The second-to-lightest gray patch on the old 24-patch Macbeth ColorChecker works well, as do bright (but not blown-out) midday clouds.

Click-balancing with the white balance tool provides a very quick way to set color temperature and tint simultaneously, especially if you placed a gray card in the image. You can always fine-tune the results using the individual Temperature and Tint controls in the Basic tab, which we’ll cover in due course.

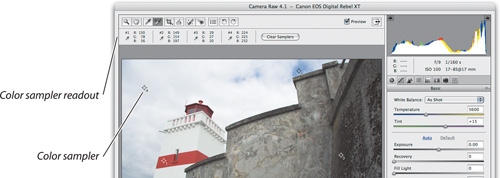

Color samplers. The Color Sampler tool (press S) lets you place as many as nine individual color samplers, each of which gets its own readout, in the image (see Figure 5-6). Combined with the static RGB readout, the Color Sampler tool lets you monitor the values of up to ten different locations in the image, which should be enough for any reasonable use.

Crop. The Crop tool (press C) lets you drag a cropping rectangle, choose one of several common predefined aspect ratios, or define your own custom aspect ratio from the tool’s pull-down menu (see Figure 5-7). The same menu allows you to clear the crop. The Camera Raw preview always shows the crop in the context of the whole image, but you’ll see the crop in filmstrip previews, Bridge previews and thumbnails, and of course in the image itself when you open it in Photoshop.

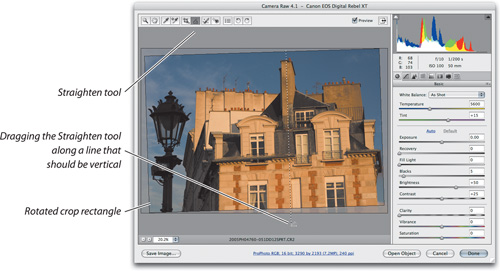

Straighten. The Straighten tool (press A) is an enormous time-saver for those of us who sometimes fail to keep our horizons horizontal. It should really be called the Straighten and Crop tool because it also automatically applies the crop that maintains the maximum rectangular image when the Crop tool is set to Normal, or a straightened crop of the specified aspect ratio when the Crop tool is set to something else. If there’s an existing crop, it’s preserved and rotated. Compared to straightening and cropping an image in Photoshop using the Measure tool, Arbitrary Rotate tool, and the Crop tool, we much prefer the Straighten tool’s speed and simplicity (see Figure 5-8).

Rotate buttons. The Rotate 90 Degrees Left and Right buttons (press L and R, respectively) aren’t really tools—you don’t have to do anything inside the image preview—but since they’re placed so closely to the toolbar (see Figure 5-5), we’ll deal with them here. Clicking on them or pressing their keyboard shortcut rotates the image preview. When you finish editing the image in Camera Raw, the rotation is applied to thumbnails and previews in Bridge, and is honored whenever you open the raw image in Photoshop.

Tip

All of the keyboard shortcuts for zooming in Photoshop (seen on the View menu in Photoshop) also work in Camera Raw; for example, press Command-Option-0 (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-0 (Windows) to display actual pixels. For the Pan tool, hold down the spacebar. Press Z to choose the Zoom tool and H for the Hand tool. Double-clicking the hand tool fits the entire image in the preview, and double-clicking the zoom tool zooms to Actual Pixels view.

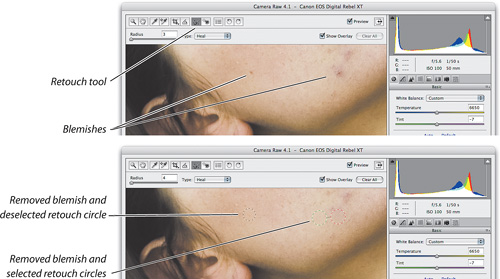

Retouch. The new Retouch tool (press B) is a spot touch-up tool, similar to the Spot Healing Brush in Photoshop (see “The Healing Brushes and the Patch Tool” in Chapter 11, “Essential Image Techniques”). To retouch a spot, select the Retouch tool, position it over the center of the spot you want to remove, and drag until the resulting circle is larger than the spot (see Figure 5-9). Press V to toggle the Show Overlay check box to see if the retouch looks good. If it doesn’t, you can drag the green dashed circle to change the retouching source, or drag the red dashed circle to change the retouched spot. You can also change the size of the circles by dragging the edge of either circle, or by changing the Radius value in the options below the toolbar. If you set the Radius when no spots are selected, you’ll be setting the default radius. You can tell that a spot is selected when you can see both the source and destination circles. A lone circle is deselected; click inside it to select it.

The Type pop-up menu in the toolbar determines how the Retouch tool works. When the Retouch tool is set to Heal, it tries to smoothly merge the source (the green dashed circle) to the destination (the red dashed circle) by matching texture, lighting, and shading. It’s more common to choose Heal from the Type pop-up menu, particularly when removing skin blemishes. To exactly copy one spot to another, choose Clone from the Type pop-up menu.

Though Photoshop has more retouching options, such as the ability to remove long scratches and power lines, there are two good reasons to perform spot retouching in Camera Raw. First, the edits are nondestructive, so you can change them later at any time; in Photoshop, actual pixels are altered in the original image. Second, it follows our recommendation to do any edits you can as early as possible in the digital workflow, so that you only have to do them once.

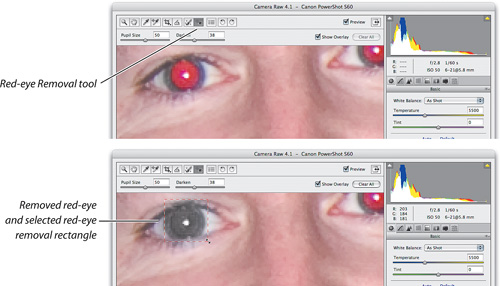

Red eye removal. The Red-eye Removal tool (press R) is a quick way to get rid of red-eye from on-camera flash. Drag a rectangle around an entire eye (it works better if you surround more eye, not less), and Camera Raw detects red-eye and applies the default correction settings (see Figure 5-10). Like the Retouch tool, you can resize a red-eye rectangle by its edges, reposition it by dragging, add multiple rectangles (most people have more than one eye), and select and deselect rectangles. When a rectangle is selected, you can change the Pupil Size and Darken values in the toolbar. Don’t make a rectangle much bigger than an eye, or you may have trouble getting the Pupil Size to be small enough.

Two sets of controls affect the preview image (Figure 5-11). The Zoom buttons and the Zoom level menu control the size of the preview image, while the Preview check box affects its state.

Zoom Level menu. The Zoom Level menu lets you choose a zoom level for the image preview. But if you find yourself using this feature, go back and read the tip about keyboard shortcuts for zooming, on page 150.

Preview check box. The Preview check box (press P to turn this on or off) applies only to the current editing tab, toggling between its current settings and those that were in effect when you opened the image. It has no effect on changes you’ve made in other tabs. To see the settings that applied before you opened the image—toggle between Image Settings and Custom Settings on the Settings menu (see Figure 5-14).

Tip

If you see a yellow warning triangle in the image area of the Camera Raw dialog, Camera Raw isn’t finished processing the image. Don’t judge image quality until the yellow warning triangle goes away.

Full-screen mode. To make the Camera Raw window fill the entire monitor, click the Full-Screen Mode button next to the Preview check box. Full-screen mode works best if you have a fast machine, because Camera Raw takes longer to refresh the dialog when it’s larger. Along those lines, if your machine is on the slow side, you can speed things up by making the Camera Raw dialog smaller.

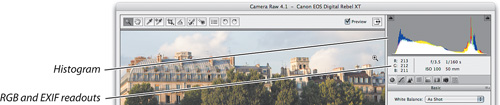

The histogram and RGB readout provide information about the current state of the image (see Figure 5-12). The histogram displays the histograms of the red, green, and blue channels that will be created by the current conversion settings, not the histogram of the raw image (which would look strange since digital cameras capture at linear gamma—all the image data would be scrunched over to the left). The histogram can show you, at a glance, exactly what’s happening to your exposure and clipping at the current image settings. If you’re unfamiliar with histograms, see “The Histogram Palette” in Chapter 7.

Note that if the clipping disappears when you set the Space menu (in the Workflow Settings) to ProPhoto RGB, you can be certain that it’s showing gamut clipping from a smaller output space.

Shadow and highlight clipping warnings. The Shadow and Highlight Clipping Warning buttons, at the top left and right corners of the histogram (see Figure 5-13), provide a quick way to check for shadow and highlight clipping. The shortcuts are U (for underexposed) and O (for overexposed), respectively. These are most useful for a quick check on the state of the image. For a more interactive clipping display that’s more useful when you’re actually making adjustments, hold down the Option key (Mac) or Alt key (Windows) while dragging the Exposure or Blacks slider.

Tip

For more information about avoiding clipped highlights and shadows, see “The Basic Tab,” later in this chapter.

RGB readout. The RGB readout (see Figure 5-12) shows the RGB values for the pixels under the cursor. The values are those that will result from the conversion at the current settings. The RGB readout always reads 5-by-5 screen pixels at zoom levels of 100 percent or less, so it may display different values at different zoom levels. When you fit the entire image in the window, you’re sampling an average of many pixels. At zoom levels greater than 100 percent, the sample size is always 5-by-5 image pixels.

EXIF readout. To the right of the RGB values is a panel that displays information from the image’s EXIF data (see Figure 5-12), if present in the image. If the EXIF readout is blank, as it will be in a scanned image, the image doesn’t contain EXIF data. EXIF data does, however, exist in images produced by digital cameras, unless the last person who saved an image chose to strip the EXIF data from the file.

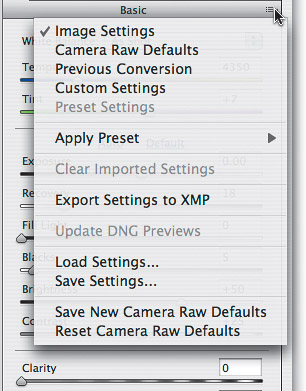

The Settings pop-up menu lets you change the settings applied to the image (see Figure 5-14). The items that always appear are Image Settings, Camera Raw Default, Previous Conversion, and Custom Settings.

Image Settings. If Image Settings is available, you’ve previously applied edits to the image. If you’re working on an image, choosing Image Settings will show you the settings that were in effect before you started editing. If the image is brand-new and has never been edited, the Image Settings values equal those of the next item, Camera Raw Default.

Camera Raw Defaults. Camera Raw Defaults is what it says—it’s the default setting that applies to all images unless and until you override it. It’s also the setting used by Bridge to create high-resolution previews when it sees a folder full of new raw images. If you find that the shipping default settings aren’t to your liking, you can set your own Camera Raw Defaults for each supported camera model. If you get yourself in a mess by doing so, you can return Camera Raw to the shipping default settings using the appropriate commands from the Camera Raw menu.

Previous Conversion. Choosing Previous Conversion applies the settings from the last image you opened in Camera Raw to the current image.

Custom Settings. Custom Settings denotes the current settings you’re applying in Camera Raw. As we mentioned previously, you can toggle between Image Settings and Custom Settings to compare your current edits with the ones that were in effect when you opened the image in Camera Raw.

You can also save your own custom settings as presets, which then become available from this menu. It’s easy to overlook the mechanism for doing so, though, because it lives on the Camera Raw menu, which—although it’s one of the most important of the static controls—is unfortunately an unlabeled button. Let’s take a look at this menu next.

Preset Settings. If you last applied Camera Raw settings to the image by choosing a preset, the name of the preset appears here.

Apply Preset submenu. Presets you’ve created with Camera Raw appear in this submenu, but it’s easier to apply them from the Presets tab.

Clear Imported Settings. Camera Raw and Bridge are no longer the only software that can read and write Camera Raw settings. Adobe Lightroom does it too, since Lightroom and Camera Raw use the same raw-processing engine. However, Lightroom and Camera Raw are not always updated at the same time, so occasionally one of them will add controls that aren’t available yet in the other. When you open a raw image using software that’s missing options that were available in the last application that edited it, you may find it difficult to control the image because it’s influenced by settings you can’t change. When that’s the case, Clear Imported Settings is a way to set those options to their default values.

Exporting Settings to XMP. The Export Settings to XMP command offers a way to write a sidecar .xmp file when you have the Camera Raw Preferences set to save edits in the Camera Raw cache. This offers a way to produce sidecar files when you want to copy the images to removable media for use on another computer while preserving the edits. If the preference is set to use sidecar files, Export Settings will export a sidecar file only if one doesn’t already exist. If there’s an existing sidecar file, Export Settings does nothing.

Update DNG Previews. When you edit a DNG file, your changes are written to the DNG metadata, but by default, the DNG preview isn’t updated. Update DNG Previews rewrites the preview so that you can see the current state of the file in applications that don’t render DNG on the fly. If you want DNG previews to update automatically, check the Update JPEG Previews check box in the DNG File Handling section of the Camera Raw Preferences dialog.

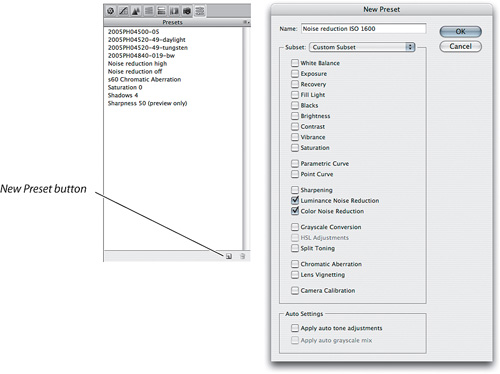

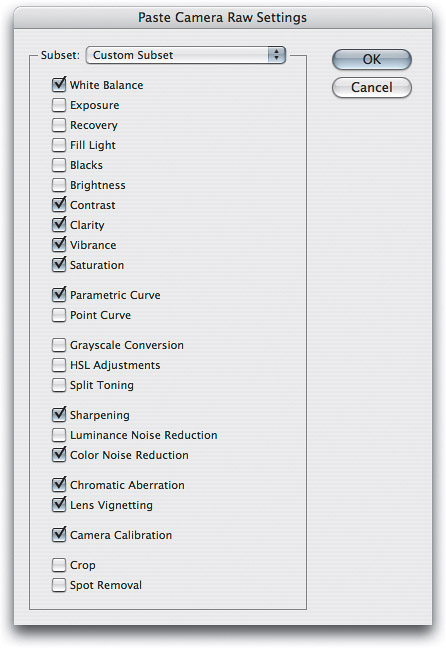

The Load Settings and Save Settings commands let you load and save settings or settings you make with any of the image-specific controls—the ones located in the tabs below the histogram. When you choose Save Settings, a dialog appears asking you which settings you want to save. This means you can save a preset for just a few options without changing any others. For example, you could create a setting that only applies color noise reduction (see Figure 5-15).

When you save settings to the default location, they appear on the Settings menu automatically. That location on a Mac is (username)LibraryApplication SupportAdobeCamera RawSettings. In Windows, it’s Documents and Settings(username)Application DataAdobeCamera RawSettings. These saved settings also appear in the Presets tab and in the Edit > Develop Settings submenu in Bridge. If you save settings anywhere else, you can load them using the Load Settings command in Camera Raw.

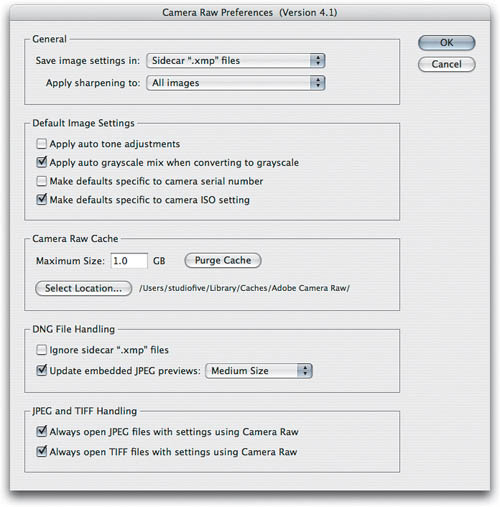

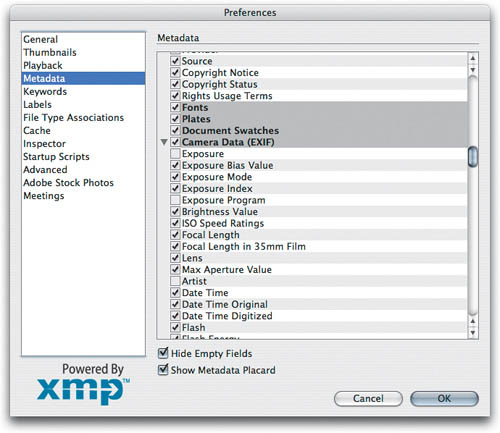

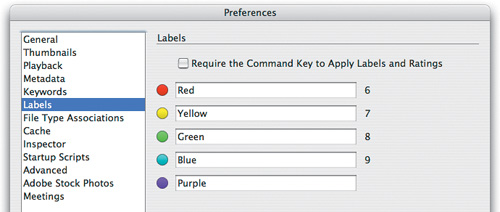

The Camera Raw Preferences (see Figure 5-16) let you decide whether your raw edits are saved in the Camera Raw database or in sidecar .xmp files, and whether to apply sharpening to the converted image or to the preview only. They also allow you to choose the location and size of the Camera Raw cache and let you purge the Camera Raw cache. Camera Raw 3.1 and later added settings that control the behavior of DNG files—they have no effect on other raw formats.

Save Image Settings In. Camera Raw treats the raw images as read-only, so your Camera Raw edits for the image get saved either in a sidecar .xmp file—a small file designed to travel with the image—or in the Camera Raw database. Each approach has strengths and weaknesses, and choose your approach using the Save Image Settings In option in this dialog.

Saving your edits in the Camera Raw database means that you don’t have to keep track of sidecar files or worry about making sure that they get renamed along with the image—the Camera Raw database indexes the images by file content rather than name, so if you rename the raw file, the Camera Raw database will still find the correct settings. The major disadvantage is that when you move the images onto a different computer or burn them to a CD or DVD, the edits won’t travel with the images.

Saving your edits in sidecar files allows the edits to travel with the images. Adobe gives you a lot of help in handling the .xmp sidecar files. By default, Bridge hides them and automatically keeps them with their respective images when you use Bridge to move or rename them. The only danger is that if you move or rename the images outside Bridge, you need to keep track of the sidecars yourself.

A solution to this potentially confusing issue is to convert your raw images to DNG format (see “The Main Control Buttons,” later in this chapter for more on this). Camera Raw treats raw files as read-only because all the vendors’ proprietary formats—Canon’s CRW and CR2, Nikon’s NEF, Olympus’ ORF, and so on—are undocumented. Rather than taking the risk of messing up the file by writing metadata such as Camera Raw settings into it, Camera Raw uses sidecar files or its own database. But DNG is a completely documented, open format, so when you use DNG, Camera Raw settings and other metadata get written directly into the DNG file itself.

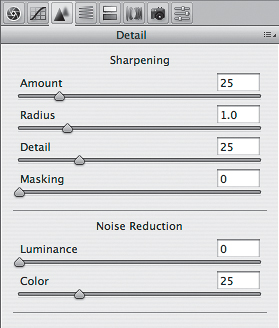

Apply Sharpening To. The Apply Sharpening To option lets you choose whether to apply sharpening to the previews and to the converted image, or to the previews only. Setting this option to Preview Images Only lets you enjoy reasonably sharp preview, but apply more nuanced sharpening to the converted images. Note that this preference only affects the Sharpness setting, not either of the noise-reduction settings, which are found on the same Detail tab as the Sharpness control (see “The Detail Tab,” later in this chapter).

If you plan to apply sharpening later in your workflow, such as in Photoshop, it’s better to set this to Preview Images Only. However, if you’re going to export final images from Camera Raw, you probably want to set this option to All Images—otherwise no Camera Raw sharpening will be applied to the exported images.

Default Image Settings. Click the Preferences icon in the toolbar to see the Default Image Settings preferences. Uncheck Apply Auto Tone Adjustments if you don’t want Camera Raw to automatically adjust each image that you open in Camera Raw; Apply Auto Grayscale Mix When Converting to Grayscale is a similar preference for the times when you convert color images to black and white using the Convert to Grayscale check box in the HSL/Grayscale tab (see “The HSL/Grayscale Tab” later in this chapter), but we think you should leave that one on. Make Defaults Specific to Camera Serial Number is useful if you own multiple bodies of the same camera and want different defaults for each camera. Conrad likes to check Make Defaults Specific to Camera ISO Setting, because he wants different ISO settings to use different default settings for noise reduction.

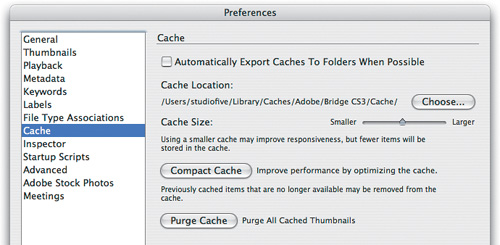

Camera Raw cache. The Camera Raw cache holds pre-parsed raw data for the most recently used raw files, which is used to speed up the following operations:

Opening the Camera Raw dialog

Switching between images in the Camera Raw filmstrip

Updating the thumbnails in the Camera Raw filmstrip in response to settings changes

Rebuilding the thumbnails/previews in Bridge in response to settings changes

The cache file sizes average about 5 MB, so at the default size limit of 1 GB, the Camera Raw cache will hold the pre-parsed data for about the 200 most recently accessed images. If you commonly edit folders with more than 200 raw files, you will probably want to increase the Camera Raw cache’s size limit. Nothing is stored exclusively in the Camera Raw cache, so purging it never means you will lose data.

DNG File Handling. The two check boxes under DNG File Handling control the behavior of DNG files. They have no effect on other raw formats.

Ignore Sidecar “.xmp” Files. This preference addresses a relatively obscure situation that arises only when you have a DNG and a proprietary raw version of the same image in the same folder, and they’re identically named except for the extension. If you edit the proprietary raw file, Camera Raw also applies the edits to the DNG, to maintain compatibility with older versions of Photoshop CS and Photoshop Element, which write sidecar files for DNG instead of writing to the DNG file itself. This setting lets you tell Camera Raw to ignore sidecar files and leave the DNG file alone in this situation.

Update Embedded JPEG Previews. This setting controls when the embedded JPEG previews in DNG files get updated. When it’s turned on, Camera Raw updates the embedded preview as soon as you dismiss Camera Raw after editing a DNG file, thereby incurring a speed penalty since the previews take time to write and save.

You can defer the speed hit by turning this item off. Then, when you want to update the previews, choose Update DNG Previews from the Camera Raw menu, which opens the Update DNG Previews dialog where you can choose the preview size.

Tip

If you want Camera Raw to use the same JPEG preview size that it applied the last time you chose the Update DNG Previews command, hold Option/Alt while choosing Update DNG Previews to skip the Update DNG Previews dialog and apply the last-used preview size.

When you choose Full Size, Camera Raw embeds both Full Size and Medium Size previews. The downside is that Full Size previews take longer to build, and make a slightly larger file. Bear in mind, though, that you can choose whether Photoshop or Bridge will get tied up generating the previews so you can continue working in the other application while the one hosting Camera Raw builds the previews.

JPEG and TIFF Handling. These two options need a little bit of decoding because the way they work isn’t obvious. Turning on the check boxes for Always Open JPEG Files with Settings Using Camera Raw and Always Open TIFF Files with Settings using Camera Raw does not mean JPEG and TIFF files will always open in Camera Raw. The clues are the words “with settings.” If you turn on these check boxes, then files in those formats will open in Camera Raw if they already contain Camera Raw settings—in other words, they will open in Camera Raw if you’ve previous edited them in Camera Raw. If you haven’t edited them in Camera Raw, they’ll open in Photoshop even if you’ve checked these options. And if you uncheck these options, files in those formats always open in Photoshop, even if you’ve edited them in Camera Raw.

Tip

The Bridge preference Prefer Camera Raw for JPEG and TIFF Files doesn’t affect how those file types open. If the images contain Camera Raw settings, it controls whether Bridge uses Camera Raw settings to render JPEG and TIFF thumbnails.

If you want to ensure that a JPEG or TIFF file opens in Camera Raw even if it doesn’t contain Camera Raw settings, you must open the file in one of two ways: Either select the file in Bridge and use the File > Open with Camera Raw command (which is also available on the context menu); or in Photoshop choose File > Open, and then change the Format pop-up menu to Camera Raw.

The main control buttons (see Figure 5-17) let you specify the action that Camera Raw will perform on your raw image.

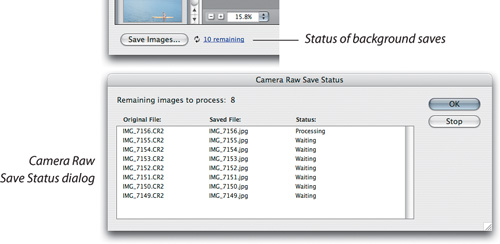

Save Image. Click Save Image (Command-S in Mac OS X or Ctrl-S in Windows) to export a copy of the raw image as a DNG, TIFF, JPEG, or Photoshop file directly from the Camera Raw dialog without opening the image in Photoshop. Clicking Save Image opens the Save Options dialog, which lets you specify the destination, the file format, any format-specific options such as compression, and the name for the saved file or files. When you click Save in the Save Options dialog, you’re returned to Camera Raw, and the file gets saved in the background.

It’s also worth noting that Camera Raw is in itself a DNG converter. If you’ve decided that you want to stay with proprietary raw files as your working files, but would prefer to hand off DNG files when you need to submit raw images (to make sure that your metadata gets preserved), you can do it straight from Camera Raw.

If you don’t want the Camera Raw dialog to go away after you’re done saving, hold down Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) to change the Save Image button into the Save button. When you click the Save button, the Save Options dialog doesn’t appear; the selected images in Camera Raw are saved using the last settings you used in the Save Options dialog.

Tip

The Save button is especially useful when you select multiple images in filmstrip mode, because the conversion happens in the background. That means that you can keep working in Camera Raw while Camera Raw exports image after image.

Open. Click Open (Command-O in Mac OS X or Ctrl-O in Windows) to close the Camera Raw dialog and open the image in Photoshop using the settings you applied in Camera Raw. These settings are written to the raw file’s metadata, and Bridge’s previews and thumbnails are updated to reflect the new settings. When Camera Raw is hosted by Photoshop, Open is the default button.

If you want to open selected images in Photoshop but you don’t want the current Camera Raw settings to be saved with the raw files (maybe you’re experimenting), press Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) to change the Open button to Open Copies. Finally, if you want to open selected images in Photoshop as Smart Objects (see “Smart Objects” in Chapter 11), press Shift to change the Open button to Open Objects.

If this button already says Open Object or Open Objects, the default behavior of the button has been changed. That’s set in the Camera Raw Workflow Options, which we will talk about soon.

Cancel. Click the Cancel button (press Esc) to ignore any adjustments you’ve made since opening Camera Raw, close the Camera Raw dialog, and return you to the host application, leaving the raw file settings unchanged. If you have many images open in Camera Raw, all of those images lose all changes you made to them in the current Camera Raw session.

To return all Camera Raw settings to the state they were in when you launched Camera Raw (either Image Settings, if the image had previously had its own Camera Raw settings applied, or Camera Raw Defaults if it hadn’t), press Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) to change the Cancel button to Reset. The Camera Raw dialog stays open after you click Reset.

Done. Click Done (or press Return or Enter) to close the Camera Raw dialog, write the settings you applied in Camera Raw to the raw file’s metadata, and return to the host application. Previews and thumbnails in Bridge are updated to reflect the new settings. When Camera Raw is hosted by Bridge, Done is the default button.

While it may be obvious that you adjust settings in Camera Raw by dragging the sliders, you can also take advantage of other adjustment tricks. Some give you more precision and others give you more speed.

You don’t have to drag the slider itself. For more precision, position the cursor over the name of an option until the cursor turns into a two-headed arrow, and drag left or right using the entire width of the monitor. This gives you finer control than you get by using the short width of a slider.

When the cursor is blinking a value or a value is highlighted, press the up arrow or down arrow keys to adjust the value. The amount of the adjustment varies depending on the setting. Add the Shift key to adjust the value by a larger amount.

Undo does work. Even though the Undo command is not available on the Edit menu when Camera Raw is open, you can still undo changes in the Camera Raw image controls by pressing the traditional Undo keyboard shortcut, Command-Z (Mac) or Ctrl-Z (Windows). Press the Undo shortcut again to toggle between the current and previous values. In addition, Camera Raw 4 has multiple undo; just add the Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) key to the Undo shortcut to move back through Undo steps, or add the Shift key to move forward through Undo steps.

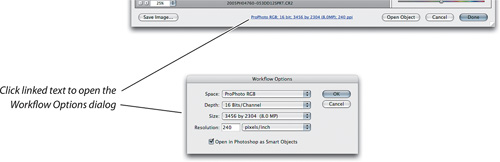

At the bottom of the Camera Raw dialog is blue underlined text that looks like a Web link. You’ll notice that the text is a line of image specifications; click the text to open the Workflow Options dialog and change the specs (see Figure 5-18). These controls apply to the current image or to all the images being converted in a batch process. The workflow options aren’t saved with individual images; the Camera Raw dialog simply continues to use the settings until you change them again.

Space. Choose a destination color space for the conversion from one of four preset working spaces: Adobe RGB (1998), Colormatch RGB, ProPhoto RGB, or sRGB IEC61966-2.1 (the last being the “standard” flavor of the sRGB standard). See the sidebar “Camera Raw and Color” for details on how Camera Raw handles the color management aspect of the conversion. Note that the space you choose here determines the boundaries for the clipping warnings in the Camera Raw dialog.

Depth. Choose whether to produce an 8-bit/channel image or a 16-bit/channel one. A 16-bit/channel file needs twice as much storage space as an 8-bit/channel one, but it provides 128 times the tonal steps between black and white, so it offers much more editing headroom.

Crop Size. Choose the pixel dimensions of the converted image. If you see a minus sign (−) after a set of dimensions, choosing those dimensions will downsample the image. Similarly, if you see a plus sign (+) after a set of dimensions, choosing those dimensions will upsample the image. The dimensions in the middle of the list (with no minus or plus sign) represent the number of pixels saved into the image file by the camera.

Tip

To use Camera Raw to resample an image to pixel dimensions that aren’t in the Size pop-up menu, use the Crop tool in Camera Raw instead. The Crop tool lets you specify pixel dimensions up to 10,000-by-10,000 pixels, so you can use it to produce a much larger file than the sizes that appear on the Size menu in Camera Raw. The Crop tool method works for downsampling too.

Resolution. Choose a resolution for the converted image. Changing Resolution doesn’t change the number of pixels in the converted image, only their density.

If you want to set image resolution or pixel dimensions with more control than you have in the Workflow Options dialog, leave the settings at the native values, wait until you’ve opened the image in Photoshop, and then choose the Image > Image Size command in Photoshop.

The image controls—the ones you’re likely to change with each image—occupy the rest of the Camera Raw dialog. The tabs are:

Basic, which deals with color balance, essential tone mapping, and overall image quality.

Tone Curve, where you can fine-tune contrast.

Detail, which provides controls for sharpening and noise reduction.

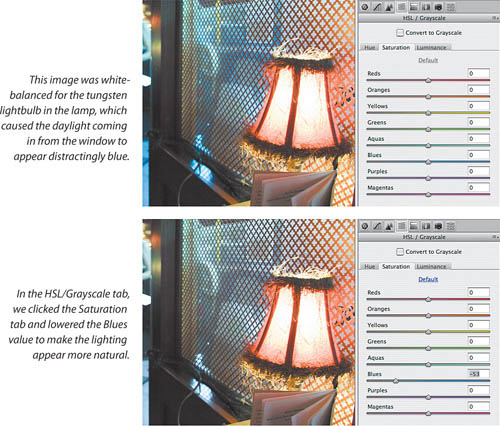

HSL/Grayscale, where you can adjust specific color ranges, or, if you turn on its Convert to Grayscale check box, tonal ranges.

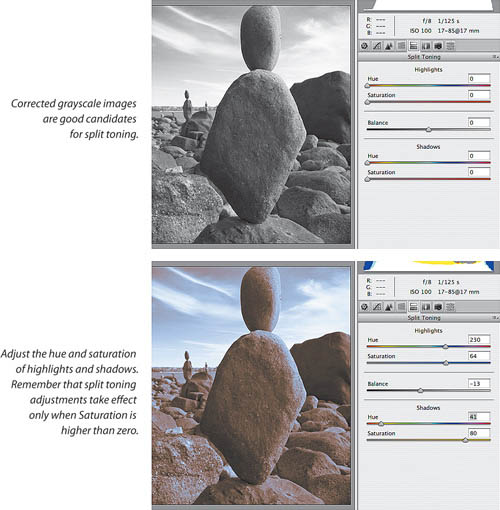

Split Toning, where you can tone highlights and shadows differently, is a technique that adds depth to limited-color images.

Lens Correction, which can correct chromatic aberration, defringing, and vignetting.

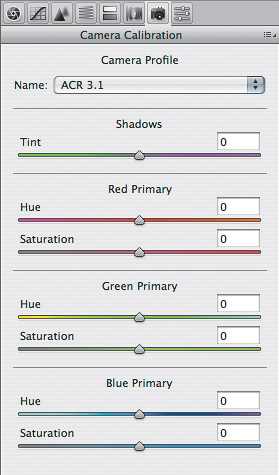

Calibration, which lets you fine-tune the built-in color profiles in Camera Raw to better match the behavior of your specific camera body.

Presets, a list of all of the presets available to Camera Raw.

You can switch quickly between tabs by pressing keys 1 through 8 together with the Command and Option keys (Mac) or the Ctrl and Alt keys (Windows). For example, on the Mac, press Command-Option-2 to display the Tone Curve tab.

Tip

On Mac OS X, Command-Option-8 is the default shortcut for enabling or disabling screen zooming for the visually impaired. If you’d rather use that shortcut for the Presets tab in Camera Raw, open the Keyboard & Mouse system preference, click the Keyboard Shortcuts tab, and change the Turn Zoom On Or Off shortcut to a different shortcut (Conrad changed it to Command-Option-9).

These image controls are really the meat and potatoes of Camera Raw, offering very precise control over your raw conversions. Some of the controls may seem to offer functionality that also exists in Photoshop, but there’s a significant difference between editing the tone mapping in Camera Raw, which tailors the conversion from linear to gamma-corrected space, and editing the tone mapping by stretching and squeezing the bits in a gamma-corrected space in Photoshop.

The more work you do in Camera Raw, the less work you’ll need to do afterward in Photoshop. At the same time, if you get your images close to the way you want them in Camera Raw, they’ll be able to withstand much more editing in Photoshop—which you may need to do to optimize for a specific output process, or to harmonize the appearance of different images you want to combine into a single one.

The controls in the Basic tab (Command-Option-1 in Mac OS X or Ctrl-Alt-1 in Windows) let you tweak the essential tonal and color qualities of an image, such as white balance and overall contrast (see Figure 5-19). It’s the default tab in Camera Raw. Three controls in this tab deserve special attention: The Temperature, Tint, Exposure, and Recovery controls. They let you do things to the image that simply cannot be replicated in Photoshop after you convert the image.

Clarity and Vibrance have no direct analogs in Photoshop, although you can replicate their effects with some effort. Fill Light is somewhat like the Shadow portion of the Highlight/Shadow feature in Photoshop.

The Contrast, Brightness, and Blacks controls provide similar functionality to Levels and Curves in Photoshop, with the important difference that they operate on the high-bit linear data in the raw capture, rather than on gamma-encoded data postconversion. If you make major corrections (“major” meaning more than half a stop) with the Exposure slider, you’ll certainly want to use the Recovery, Brightness, Contrast, Fill Light, and Blacks controls to shape the raw data the way you want it before converting the raw image. With smaller Exposure corrections, you may still need to shape the tone in Camera Raw rather than in Photoshop, especially if you want to avoid shadow noise in underexposed images.

Tip

There are an awful lot of controls in Camera Raw, but unlike with Photoshop, it’s easy to remember what order to use the controls to preserve the best image quality. Adobe intentionally designed the control layout so that you can simply go through the tabs from left to right, and within each tab, adjust the controls from top to bottom.

The Saturation control in Camera Raw offers slightly finer global adjustments than the Hue/Saturation command in Photoshop, though unlike the Photoshop command, it doesn’t allow you to address different color ranges selectively. But in Camera Raw 4.1 or later, you can do that in the HSL/Grayscale tab.

White Balance. The two controls that set the white balance, Temperature and Tint, are the main tools for adjusting color in the image. Setting the white balance correctly should make the rest of the color more or less fall into place in terms of hue. Note that the “correct white balance” includes (but isn’t limited to) “accurate white balance”—you can use white balance as a creative tool, too.

Temperature. The Temperature control lets you specify the color temperature of the lighting in Kelvins, thereby setting the blue-yellow color balance. Lowering the color temperature makes the image more blue to compensate for the yellower light; raising the color temperature makes the image more yellow to compensate for the bluer light. If this seems counterintuitive—we think of higher color temperatures as bluer and lower ones as yellower—the trick is to remember that the Temperature control compensates for the color temperature of the light, so if you tell Camera Raw that the light is bluer, it makes the image yellower.

Tip

If you can’t figure out the white balance for an outdoor shot and the White Balance Eyedropper isn’t helping, try choosing Daylight from the White Balance pop-up menu as a starting point. Automatic white balance may not work properly with a scene dominated by a color that isn’t neutral, such as a green forest.

Tint. The Tint control lets you fine-tune the color balance along the axis that’s perpendicular to the one controlled by the Temperature slider—in practice, it’s closer to a green-magenta control than anything else. Negative values add green; positive ones add magenta.

Figure 5-20 shows an image as shot, and with some white-balance adjustments that greatly alter the character of the image. Notice that the adjustments involve the use of both the Temperature and Tint sliders.

The white-balance controls let you alter the color balance dramatically with virtually no image degradation, which you simply can’t do once the image is converted and opened in Photoshop. The freedom with which you can reinterpret the white balance is one of the main advantages of capturing raw rather than JPEG images.

Tip

Because half of the linear data in a raw capture describes the brightest f-stop, many digital photographers use the Expose to the Right (ETTR) technique. With ETTR, you set the camera exposure so that as much data as possible is as far to the right of the camera’s histogram as possible, but without clipping the highlights. As a result, you’ll probably have to lower the brightness of each image in Camera Raw, but it’s worth it: ETTR optimizes the signal-to-noise ratio (translation: image noise becomes less visible).

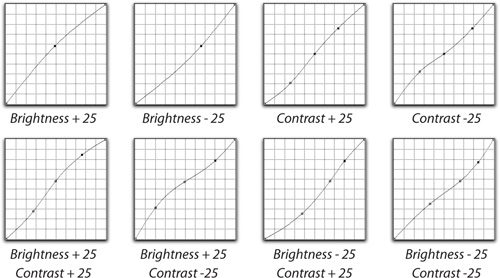

Tone-mapping controls. Learning how the four tone-mapping controls—Exposure, Blacks, Contrast, and Brightness—interact is essential if you want to exercise control over your images’ tonal values. It may not be obvious, but the controls work together to produce a five-point curve adjustment.

Exposure and Blacks set the white and black endpoints, respectively. Brightness adjusts the midpoint. Contrast applies an S-curve around the midpoint set by the Brightness, darkening values below the midpoint and brightening those above. Figure 5-21 shows Brightness and Contrast adjustments translated approximately into Photoshop point curves.

Let’s go into even more depth on each of these controls.

Exposure. The Exposure slider is first and foremost a white-clipping adjustment, like the white triangle in the Levels dialog in Photoshop. Half of the data in a raw capture is devoted to describing the brightest f-stop, so placing the highlights correctly is your highest priority. First set the Exposure slider, holding down Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) to see the clipping display, so that the only clipping is on specular highlights. If this causes the overall image to be too dark, then raise Exposure back up and use the Recovery slider to restore the highlights (see Figure 5-22).

Large increases in exposure value (more than about three-quarters of a stop) will increase shadow noise and may even make some posterization visible in the shadows, simply because large positive exposure values stretch the relatively few bits devoted to describing the shadows further up the tone scale. If you deliberately underexpose to hold highlight detail, your shadows won’t be as good as they could be. We certainly don’t advocate overexposure—perfect exposure is always best—but slight overexposure is often better than significant underexposure.

Recovery. The Recovery slider offers the amazing ability to let you recover highlight information from overexposed images. Figure 5-22 shows a fairly typical example of highlight recovery. The actual amount of highlight data you can recover depends primarily on the camera model, and secondarily on the amount of compromise you’re prepared to tolerate in setting white balance. But it’s not at all unusual to recover two-thirds of a stop, and it’s often possible to recover more.

Tip

Don’t forget to use the shadow and highlight clipping warnings (press U and O keys to toggle them); they help you see whether you need to increase or decrease your Blacks and Exposure values. See “The Histogram and RGB Readout” earlier in this chapter.

In Camera Raw 3, the only way to recover highlights was to set Exposure to a negative value. That still works, but naturally it often makes the image darker than you want it to be, which often requires additional Tone Curve tweaks. In Camera Raw 4, the addition of Recovery lets you set Exposure to a more reasonable value.

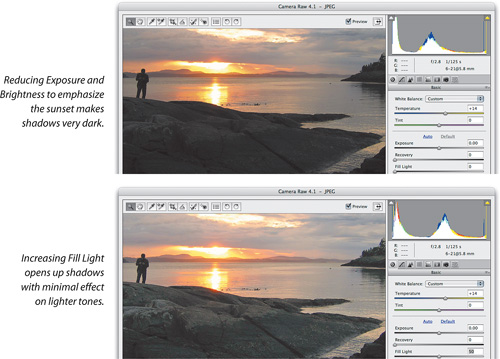

Fill Light. The Fill Light slider opens up shadows in a way that isn’t easily reproduced by Brightness, Contrast, or the Tone Curves (see Figure 5-23). For example, if you open up the shadows with a curve, you might lighten the rest of the image too much. Fill Light gets around this by lightening the shadows as much as it can without affecting the highlights.

You may experience a slight delay the first time you drag the Fill Light slider for each image, because it initially generates a mask, which Fill Light uses to restrict the adjustment to the shadows. On a slower machine, drag Fill Light a little, let go, and wait for it to build the mask before tuning your adjustments. You can’t see or adjust this invisible mask, but it works well in most cases.

Blacks. The Blacks slider is the black-clipping control, like the black input slider in the Levels dialog in Photoshop. But because the Blacks slider operates on linear-gamma data, small moves make bigger changes than does the black input slider in Levels. If you think the default value of 5 is too aggressive, you may want to set a lower default value.

Brightness. The Brightness control is a nonlinear adjustment that works very much like the gray input slider in Levels. It lets you redistribute the midtone values without clipping the highlights or shadows. Note, however, that when you raise Brightness to values greater than 100, you can drive 8-bit highlight values to 255, which looks a lot like highlight clipping. But if you check the 16-bit values after conversion, you’ll probably find that they aren’t clipped.

Contrast. Contrast applies an S-curve to the data, leaving the extreme shadows and highlights alone. Increasing the Contrast value from the default setting of +25 lightens values above the midtones and darkens values below the midtones, while reducing the Contrast value does the reverse. The midpoint around which Contrast adds the S-curve is determined by the Brightness value, so if Contrast isn’t doing what you want, make sure Brightness is set correctly.

Intensity controls. Camera Raw 4 features three controls in this section, where Camera Raw 3 contained only the Saturation command.

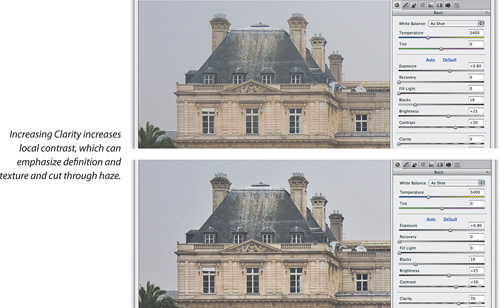

Clarity. The Clarity slider controls local contrast, and can help produce that quality some photographers call “pop.” Instead of adjusting contrast uniformly, Clarity adjusts contrast among adjacent areas of light and dark within an image (see Figure 5-24). Most images benefit from applying a moderate amount of Clarity, but as you increase the value, back off if you start to see unsightly halos around edges. Also, go easy when applying Clarity to portraits, because the way Clarity accentuates details and texture is usually not flattering for human faces. Clarity can dramatically improve images that naturally have low local contrast, such as reflections, foliage, and subjects photographed through haze.

Perhaps you’ve used Photoshop to enhance local contrast by setting the Unsharp Mask filter to a high Radius and low Amount value. The Clarity slider is based on a similar principle, but with additional processing. Clarity can appear to have a sharpening effect, but it’s important to note that Clarity is not a substitute for sharpening. For that, there’s the Detail tab.

Vibrance. The Vibrance slider is intended as a “safer” version of the Saturation slider. It applies a greater increase in color saturation to colors that are not already saturated (see Figure 5-25). For example, if you increase saturation for an image that contains both muted and saturated reds, the muted reds become more saturated but the bright reds are prevented from becoming ridiculously saturated. It’s a good way to improve color with less of a chance of colors going out of gamut.

Vibrance has one more key function. The Photoshop team built skin-tone protection into Vibrance, so you can boost image saturation much further before people in your image acquire radioactive tans.

Saturation. The Saturation slider adjusts color intensity evenly for all colors. While every image editor needs a Saturation feature, the fact that Camera Raw now has Vibrance means that you may reach for the Saturation slider less often than you used to.

Improving printed output with the new camera raw controls. The tonal range and color gamut of print is so much narrower than what your camera and monitor can produce that it isn’t unusual to spend a lot of time using layers and masks in Photoshop to shoehorn an image into the gamut of your printed output. Now, in Camera Raw 4.x, you can achieve many of the same goals just by using the four new sliders—Recovery, Fill Light, Clarity, and Vibrance. Recovery and Fill Light are quick and reliable ways to move highlight and shadow detail a little closer to the midtones and away from the extreme ends of the tonal scale that are harder to print. Because compressing detail into the midtones usually means you lose a little contrast, you can then use the intelligent Clarity and Vibrance sliders to preserve and enhance contrast in the resulting range of tones and colors without pushing them back out to the extremes, as the Contrast slider would.

It may not be possible for you to use Camera Raw to completely prepare an image for printed output—for one thing, you can’t load a printer profile and visually check your adjustments against it—but those four sliders can reduce the amount of work you have to do with layers and masks in Photoshop to compress an image’s tonal and color range.

When you click Auto (see Figure 5-26) in the Basic tab (it’s on by default), Camera Raw tries to come up with optimum settings for each image, essentially autocorrecting tone and exposure. While the word “auto” usually makes us squirm, this feature is more sophisticated than it might seem at first glance.

However, keeping Auto as part of the default setting makes it difficult for you to learn the behavior of a camera because Camera Raw adjusts each image individually, so you don’t get to see a consistent baseline interpretation. Beginners will likely find that Use Auto Adjustments provides a quick way to get decent results, but it also makes it much more difficult for them to learn the relationship between shutter speed, aperture setting, and the result. If you don’t want Auto to be applied to new images by default, click the Preferences button in the Camera Raw toolbar (Command-K in Mac OS X or Ctrl-K in Windows), and in the Default Image Settings options group, uncheck Apply Auto Tone Adjustments.

Tip

To free up space in the Camera Raw window, Camera Raw 4 lacks the Auto check boxes that were next to each slider in Camera Raw 3.7 and earlier. You can still reset each slider individually—just double-click a slider.

In Camera Raw 3, Auto was a toggle; you could turn it on and off with a shortcut. However, its behavior was confusing in the way it interacted with the defaults and any settings you changed. In Camera Raw 4, Auto now works like other options. Once you apply it, you can either undo it or apply a different option or preset.

Camera Raw contains default settings for images shot by each camera model. They’re applied as you download images from a camera. You can create your own defaults, and the image metadata will tell Camera Raw which default to use for each camera model.