Chapter 1

Recording Analysis: Domains, Disciplines, Approaches

This chapter sets the context for the study of recording analysis, and introduces the process. A sizeable portion of this context has been explored in the field of popular music studies. Those writings have provided valuable information and models, especially pertaining to disciplines outside the domains of the record. Popular music studies and popular music (and rock music) analysis topics will appear often in this chapter, and interspersed throughout this writing. Recording analysis emerges from these fields as a broader and more inclusive examination of the recorded song; recording analysis owes much to these origins of the study of popular music.

The record reshaped the listening experience and influenced the music itself—profoundly. The record is a finely crafted performance; it reframes notions of performance, composition and arranging around a production process of added sonic dimensions and qualities. It shapes spans of time and captures spontaneous moments. The record’s influences are broad in scope, and worldwide in their impacts. A general accounting of them here helps to establish a meaningful point of reference.

Further establishing this context is an examination of the central issues surrounding analyzing each of the three domains of the record: music, lyrics and recording. The domains are examined separately to identify central concerns and issues to be engaged in their analysis. This provides background information and an overview to inform the upcoming chapters on each of these domains, as well as chapters pertaining to the analysis process and framework.

Disciplines outside the domains of the record have contributed significantly to popular music studies and analysis, some since before the field formally began. Others have recently been applied to the analysis and study of popular music. The most pertinent disciplines are identified and introduced here, with some indication of their scope, focus and potential application. These topics might serve to establish a context for recording analysis, depending on its goals.

Recording analysis and related concepts are introduced. A framework of four principles and several concepts, and a flexible, functional process, forms the approach to recording analysis that is presented throughout this writing. Important to the approach is its flexibility and transparency. The framework establishes a general scheme of inquiry from which the process may forge or explore many paths— paths that are unique and appropriate for the individual recorded song. From these paths, pertinent conclusions may emerge to illuminate the track.

RECORDS AND RECORDED MUSIC

Since its development over 100 years ago, the record has changed music (“music” being used in the broadest sense) in a great many ways. The record as a commodity emerged and has had significant, worldwide commercial influence and varied and broad social impacts. The record is a musical voice of the people, of all people—any person from the common and the elite, the sacred and the profane, and all between or beyond. It has changed how we relate to music and how we engage music, and it has changed the content of music. Much writing from many directions and disciplines has covered aspects of these topics and much more.1 Our focus here is on the ways the record has shaped music and the experience of listening to the recorded song, of which the following section is but a glimpse, serving to set some context for our study of recording analysis.

The record shifted the ways we engage music. Before the record, music listening was a communal, group activity; it took place in concert halls, churches, pubs and other public places. Music was performed live and in front of the audience, it took place in real time and was created spontaneously, and once the performance was over all that remained of it were the memories of those in attendance. In the early days of recorded music—when listening to records (or perhaps cylinders) was largely a parlour or living room experience—the record (plus phonograph) had become the chamber music of the twentieth century; this soon evolved into something else. With the record one can have any music, any time, any place. Music has become personal (we own the records we choose from millions of options, and we can identify deeply with them) and portable (we take music with us wherever we wish and listen whenever we wish). Music listening has become largely solitary (Eisenberg 1987) as listening is often an activity individuals do when alone; increasingly, music listening is isolating, as we close ourselves off from the world with our earbuds.

Along with changing these processes of engaging music, the record changed the substance of music. It spawned types of music that could not have been possible without it—and continues to do so. Rock music, and much popular music, is created and disseminated as records; the medium and the music are fundamentally joined. This is music that is both created and heard, with musical qualities that are the result of the recording process, of the media that stores and delivers it, and of the reproduction methods that presents it to the listener.

Composition, performance and recording production are linked and entwined. Performers and performances generate musical ideas in “the same sort of considered deliberation and decision making as musical composition” (Zak 2001, xii). Recorded performances are intentionally crafted with great attention to details, and performer interpretations are filled with nuance and precision— all intentionally captured, then carefully combined into the sound of the record. There is a team of skilled individuals that contribute to the record—in addition to performers there are songwriters, arrangers, lyricists, engineers, producers, all of who might have overlapping roles. Those that shape the record are called “recordists” here, despite their varied roles of producer, engineer, mix engineer, mastering engineer, tracking engineer, and the host of other formal and informal positions and titles.

The composition of the music might continue or might even occur during the tracking of various performances, where the sound qualities, performance techniques and expression of the performers become wed to their performances and interpretations of the musical ideas to make something larger, more substantial. The traditional approach to the musical setting or arrangement shifts to the more immediate and subtle to incorporate the qualities of the performance, and also to embrace the techniques and sounds of recording. These performances and the arrangement next receive their final shaping, are combined and mixed into the final form of the track itself. In this process all stages influence one another, and they function inseparably. The composition is the record and the performance. The record is the composition that emerges from the captured, created and crafted performance that is guided and realized through recording technologies.

This brings us to recognize that the record is not only a performance and a composition, but something else as well. It is also a set of sound qualities and sound relationships that to a great extent do not exist in nature and that are the result of the recording process. These qualities and relationships create a platform for the recorded song, and contribute to its artistry and voice.

The sound qualities of the recording, then, contribute fundamentally to the artistry and sonic content of the record. The recording’s sound adds qualities not found in nature, and reconfigures those qualities the listener already knows. The result is a reshaped sonic landscape, where the relationships of instruments defy physics, where unnatural qualities, proportions, locations and expression become accepted as part of the recorded song, of its performance, of its invented space. Sonic reality is redefined within the impossible worlds of records—and accepted without hesitation by listeners. Records can establish a “reality of illusion” (Moorefield 2005, xiii); a crafted world for the record that is uninhibited by the reality of natural sound relationships, where illusion is reality, where everything that can be created technologically is accepted as reality for the individual recorded song.

Given the high degree of control and scrutiny available in the production process, we should believe that what is sonically present on a record is what was intended, even if seemingly arbitrary or flawed. What is present is part of the record’s artistic voice, and it is integral to the primary text of the track, “constituted by the sounds themselves” (Moore & Martin 2019, 1). Should seemingly unintended sounds be present, those ‘flaws’ were either not heard during the making of the record, or a choice was made that allowed them to remain. What is on the record are those sounds and performances that were selected and combined from all that were recorded or that were generated by, created within or captured through the recording process. The process of making a record is exacting, and the sounds of the final record are carefully crafted; what is there was put there, or was allowed to remain. The record can be crafted such that a flawless performance results—a performance perhaps perfect in its flaws, as ‘flawless’ is in relation to conventions and artist intentions, and therefor open to the subjectivity of context. Related, the record may be perceived as flawless, though by some accepted norms it might be considered technically flawed or the performance may have qualities that might be perceived by some as imprecise (an example might be the often criticized vocals of Bob Dylan).

The record then comes to represent the definitive version of the song and the performance of the song (in as much as the two can be separated). The record represents the correct version of the song, and any covers of the song by others or future performances of the artist are gauged in reference to the original. Of course exceptions to this occur, but when the original is well known, the record becomes widely accepted and recognizable in this singular form. Here the record becomes a permanent performance, a performance frozen in time along with all its nuance of expression in dynamics, timbre and time captured—and along with everything else the individual listeners or society associates with it.

Differing from live performance, this recorded performance (that is permanent) allows repeated listenings and reflection, deeper examination and more personal interpretations by the listener, and discoveries of the subtleties of the music, the lyrics and the recording. Just as the listener finds something new in music with repeated hearings, and lyrics can reveal something new to the listener upon reflection or new listening, well-crafted recordings can reveal “new facets and nuances on playing after playing” (Gracyk 1996, viii). Albin Zak (2001, 156) shares: “one of the great delights of listening to a well-mixed record lies in exploring aurally its textural recesses, its middle ground and background, and discovering that it offers levels of sonic experience far beyond its obvious surface moves.” The sonic dimensions of the recording will reward the listener’s attention with further enrichment of the recorded song; the experience of the record is enhanced and supplemented by the recording, and the listener’s interpretation is further shaped by it.

ANALYZING THE RECORD'S DOMAINS

Analysis can demystify the record. It can provide clarity to its materials and their relationships, illustrate its structure and shape, and make its movement and energy more coherent to the listener/analyst; it may even allow one to peer into the content of its meaning. Analysis can provide some objectivity and depth of substance to listener interpretation, or to cultural analysis. In studying popular music, writings from numerous fields have examined various factors within and external to the song’s music and lyrics, and a few approaches also incorporate aspects of the record (see below). Analysis has the potential to illuminate how the recorded song works, and what it communicates. This study can allow the analyst to develop an intimate knowledge of the song and the track, the artist and the genre; it can make the record intelligible.

Music analysis may bring benefits to understanding music, and thus to understanding the recorded song. So can an evaluation of the lyrics. Music and lyrics might be most easily analyzed individually, isolated from one another’s influence. Within the song’s artistic statement, however, they are not so readily divided, with their interactions and interrelationships playing key roles in the experience of the song. The interactions and interrelationships include the sounds of the recording; these greatly shape the experience of the record—potentially as much as the music and the lyrics. Thus, an analysis of the recording adds another layer of materials, contributing fundamentally to the multidimensionality of the record. Recording analysis embraces these three domains equally.

Popular Music Analysis

Analyzing music has a centuries long history, with established traditions, conventions, theories and methods. Some of this will be in play here, but much traditional music analysis seeks information and relationships that simply are not relevant in popular song, and especially in the popular song since recording became prominent. Traditional music analysis has long looked to explain music through study of its pitch and rhythmic materials, and their generation of melodic, harmonic and formal relationships. Traditional analysts sought (most still seek) the sources of unity and coherence in musical works through examination of harmonic and formal structures, (Cook 1987, 4) perhaps including thematic materials and their melodic and rhythmic elements. Less interested in the other dimensions of music, the traditional analysis process centers on score study. “The tools for analyzing ‘serious’ music assume a definitive written score which is regarded as the record of the ‘composer’s intentions.’ Those distracting elements that ‘creep in’ during performance can be ignored as irrelevant: the music is structure, pitches and rhythms” (McClary and Walser 1990, 282). Traditional music analysis is bound to the score and its content. With no small irony, such score-based analysis may be entirely generated through sight, without accessing or taking into account the actual sound of the music.

Music analysis for popular music has many differences, and many challenges. Traditional approaches to music analysis are mostly inadequate and some are irrelevant; this makes sense, as the music and factors around production of popular music are significantly different. To start, three central matters are:

- The music is the recorded performance, bringing performance aspects to be central to musical content.

- As this recorded performance is not notated, the analyst engages the sound of the music itself, and is brought to decide on transcription matters.

- Musical styles are markedly different from Western art music, and there is an absence of tools and techniques for the analysis of popular song.

It is obvious but significant: musically, popular music’s styles are considerably different from art music, and also from one style of popular music to another (though perhaps less of a difference than to ‘serious’music). Any analytical method suitable for popular music needs to be flexible enough to meaningfully examine those elements central to the individual song and its particular musical style. The principles of traditional analysis are often of limited use here. The emphasis on harmony in traditional analysis will yield little information in many popular music genres, as the harmonic language of much popular music is limited to a few chords in recurring patterns—though certainly some styles and songs contain more involved and even quite complex harmonic relationships and structural designs.2 Instead, it is typically other elements that create interest and carry expression—not the least is what Albin Zak (2001, 22) has simply called the record’s “sound.”3 The skills learned for traditional music analysis are to be redirected and augmented to be relevant and useful for examining popular music—choices of what is worth studying will shift to that which shapes the identity of the individual work, and away from universal theory. Indeed, a theory for popular music seems well beyond possibility, not only because of the breadth of styles, but also because so few songs within any style have undergone meaningful, rigorous examination (Moore 2012a, 2). With this shift of approach comes the need to develop appropriate analytic tools and methods for these overlooked elements, and to construct a vocabulary and theoretical models with which to adequately address them (McClary and Walser 1990, 282).

Among these ‘overlooked elements’ are the qualities the performance brings. The matters of performance that are not reflected in the pitches and rhythms of the written score are integral to popular songs. For example, expressive shaping of dynamics and intensity shifts of timbre of individual lines and composite textures can take on prominent roles in a track’s movement and expression. When performances don’t comply with the rigid Western metric grid and pitches don’t conform to diatonic tunings, for instance, this is part of the essence of the performance; it is part of the essence of the music. This is a matter of substance and style, and also an element of expression; it is not a reflection of inability or poor training. All this is especially prominent and integral to vocal lines.

A significant issue arises here. How can one study these musical materials, relationships, and performance qualities when they are not notated, when they are represented only within the listener’s fallible memory, experienced from one fleeting moment to the next, and perceived differently, subjectively, by every listener? The music exists only as captured and crafted performances, on record. Should the analyst now try to transcribe the performances—and seek to do so without distorting their content? Can the analyst attend to evaluating all of the nuance and detail of the music from memory, or perhaps from copious (or sketchy) notes, but not notation? Some sort of transcription is often helpful to examine materials deeply or to illustrate points of an analysis, and as Peter Winkler (2000, 39) notes, “a transcription can make a performance ‘hold still’ so that we can observe it—or some traces of it—in detail.” Still, one significant quality of popular music is that it resists conformity to Western notation, in fact it can defy it—and this is one of its characteristic qualities. This leads me to be a reluctant advocate of the strategic use of transcription, because it is especially useful to bring those materials and passages that present or generate the identity of the track into focus. Transcription as an exercise pulls the analyst into the music, and introduces them to detail and nuance they might not otherwise engage. Transcription brings the analyst to become intimately aware of what is truly meaningful within the sound itself— whatever the element. Every sound of the music does not need to be transcribed for an analysis to be relevant and successful. The challenge is to identify what deserves the focus and detailed attention of transcription. Which parts does one transcribe, and what level of detail must one capture to adequately inspect essential qualities? And, at what point does transcription into notation distort the qualities of the part, and thereby the track?

An absence of analytical tools to evaluate popular song’s materials, an absence of a musical score to make materials readily accessible for critical examination, an overwhelming amount of sonic detail that is vital to the music, and no universally applicable systems of organization for musical syntax or structure, are some of the music analysis challenges of popular songs. These are challenges most analysts with traditional preparation in music theory and musicology may be unprepared to engage—and this only begins the list of challenges in analyzing records.

Lyrics in Popular Music Analysis

Popular music is overwhelmingly ‘popular song.’ Song lyrics bring added qualities of realism, everyday experiences, tangible concepts and communication to popular music; the songs communicate directly and in readily understood ways, using the language and imagery of everyday conversation, presenting the topics and events that mean the most to common people. Historically, this dimension is not prominent in ‘serious’ music—especially in the largely dominant instrumental forms, where music is abstract, absolute, isolated within its own patterns of organization, not connected with worldly matters, and often intended to speak to an elite, educated audience.

The language of popular song is colloquial—everyday words and expressions, often grammatically incorrect, and often slang. The language supports this sense of intimacy with the speaker/singer, and also a sense of casual and informal, direct and undisguised communication. The language may reflect a sense of social standing, a sense of culture and more; this reinforces the interconnectedness of the listener, language and the song itself.

While art songs, opera, liturgy and choral works offer certain text-setting conventions and bring some concepts to bear in analysis, popular song is starkly different. Dai Griffiths (2004, 24) has noted:

In contrast, lyrics are written to be sung, and communicate differently than poetry. Popular song speaks directly to the listener, at times perceived as to them alone. Its voice can be up close, at an interpersonal distance the listener allows few to enter in real life, and it can seem personal and private—this is in stark contrast to being detached from the voices projected from the stage or emanating from the choir loft. Popular music’s singer is the intimate stranger.

Lyrics provide sound qualities and rhythmic elements that enliven the meaning of words, and may also function as musical elements. Indeed, in some genres and tracks, the sound of the text—the tones of the voices themselves—are themselves more meaningful and more significant to the listener than the words that are sung.4 It is not uncommon for sung lyrics to be only partially understood, and perhaps not understood at all. No matter if lyrics are clearly understood or not, the role of the vocal line is central—for its sounds and rhythms, its dynamics and expression. These are contained within the lead singer’s performance—the message it presents and for the character it projects, as well as the delivery of the song—that is the dramatic core of the song. The persona of the singer carries drama and enhances the performance and the song’s content. A duality of the singer and the accompaniment— the individual above all those who are in the background—is established. The singer of popular music exhibits great subtlety of sound qualities and expression that are fundamental aspects of its message and musical content, as well as power of expression—with nuance only audible in recordings. The vocal line begs for transcription, as it contains much that is important—with its subtleties of expression in musical elements, language sounds and nonverbal sounds it is intricate and filled with significance.

In addition to the sonic qualities of the singer’s voice, lyrics’ sounds originate from their text. Conventions from poetry are often reflected in lyrics—in the structures of their stanzas and lines, and use of poetic devices. These may provide guidance for analysis of sound and rhythm, in addition to poetic/ literary devices, structure and content.

The literary content of lyrics will typically support the song’s structure (integrating the structures of the music and the lyrics). In the interdisciplinary study of popular music, literary analysis of lyrics has been around since the beginning—in fact it preceded meaningful music analysis of popular music. Journalists and academics evaluated lyrics in many ways, such as according to literary principles, as poetry, related to meanings, related to current social influences, and related to how the song might reflect on the personal life of the artist, to identify a few. Interpretations of lyrics take a great many forms, as well as degrees of focusing on the text itself. The literary content of the lyrics certainly has a place in analysis. A danger is to place too much weight on the text, at the expense of the music—or the reverse. It can be a challenge to determine an appropriate balance of music and lyrics for the individual song—a balance that illuminates the song’s message and its music.

Lyrics communicate the message of songs; they deliver narratives, stories, and more. The text can elicit meaning on many levels. Some songs plead for literary analysis of richly intricate content, and others scream their social positions. Audience members are eager to conceive their personal interpretation of lyrics. The analyst, too, might engage these realms—as will be explored below.

Analyzing the Recording

The recording is a third layer of the track (a third stream of data), and its qualities are examined equally with music and lyrics. This is the central topic of this book. The sound qualities of the recording add dimensionality, substance, and character to the record—they transform the song into the track. They are integral, just as any musical element and qualities of the lyrics. They shape listener response and the expressive qualities of the record; they contribute fundamentally to the experience that is the recorded song.

That recorded song is sonically different from a live, unamplified performance might be recognizable to the listener—or the experienced music analyst—without the differences being known, or identifiable. The factors that shape the recording are largely outside normal listening experiences—in fact, perceiving some of the elements of recordings actively contradicts listening processes that have been learned and utilized since birth (some perhaps before). Many elements of recordings have likely never been experienced fully by listeners, and the reader likely is unaware of some of the elements. That the elements are previously unknown, have never been consciously experienced and are often subtle, presents the necessity of learning—learning what might be present, learning how to listen for the elements, learning how to hear the elements’ qualities and activities. The reader will be introduced to these qualities and guided in learning listening skills to address these challenges.

The recording is examined in ways mostly different from music. Though the concepts of structure, patterning, typology, movement, shape and others may be consistent with music analysis, the content of the recording’s elements is obviously different. These concepts are adapted for insight into recording’s elements. The elements of recordings are varied, and each requires a different approach. In general, elements exist in two basic states—elements that are active (that exhibit change over time) and elements that are stable. Stable elements are defined by their qualities and characteristics, as they exist throughout a song or within certain substantial portions. All elements of the recording have the potential to exhibit changes of state or value, and create events of shape (often in patterns) and speed (sometimes rhythm)— how much change, in what direction, at what rate, etc. This brings significant potential for widely varied qualities in the recording, and significant changes and characteristics in the recording’s elements—a state that allows the recording to have an equal potential to be as significant as the other domains.

Listeners/analysts listen for conventions; we recognize conventions, or relate what is heard to conventions we know. Some conventions have evolved for certain elements, and some characteristic qualities have emerged in other elements. These help to define the ‘sound’ of various types of music, and their production styles. A systematic, orderly arrangement for some of the recording’s elements has loosely coalesced in some styles of music—though constantly evolving, and at times suddenly shifting. Syntax is apparent within most records; it appears in the ways characteristic sounds and relationships of sound qualities (elements) are defined, and in the progressions of sound relationships that are present in various styles of music. These bring a sense of organization, syntax and style to the elements, and to the record. Evaluating the recording’s elements requires devising suitable tools, approaches and techniques.

It is important to remember here, the sound qualities of the recording do not exist in notation. A collection of quasi-notational diagrams and X-Y graphs has been devised to transcribe the recording’s elements into a written form. This collection serves as a tool to observe, collect, and bring to visual form elements’ activities and characteristics, and to ‘hold them still’ for study. The graphs and diagrams are created in a transcription process—very similar to transcribing music. Emerging from this process will be some vocabulary for describing sound and the sound qualities of recordings. Through this vocabulary the elements can be described and discussed without relying on the typical personal, subjective and inexact ways we are inclined to use to talk about sound (Moylan 1992 and 2015). The analyst will be led to engage the subtleties of the recording, and to compile information on the elements that can be studied and compared to the other domains. Before this can happen, the analyst needs to accurately hear the elements. Engaging the listening process, and learning to hear the qualities of records, will bring the reader/listener to accurately compile information on the recording—a necessary first step toward evaluating them (Moylan 2017). Praxis studies engaging these skills are identified when topics arise, and appear in Appendix A.

OUTSIDE DISCIPLINES IN POPULAR MUSIC ANALYSIS

Outside the domains of music, lyrics and the recording there is much else to consider. While traditional approaches to music analysis might typically not extend far from the composition itself, there are disciplines and subject areas outside music and lyrics that are integral to the study of popular music. Popular music is not autonomous, self-contained from external influences, or transcendent of social interests as ‘serious’ music is inclined to be perceived (by artists, musicologists, audiences, etc.). These other disciplines that follow can contribute to or provide rich understanding of a different sort. The perspectives of these fields can add a great deal to an analysis of the record. Rock and popular music studies originated with scholars in disciplines outside music.5 Adam Krims (2007, 185) explains:

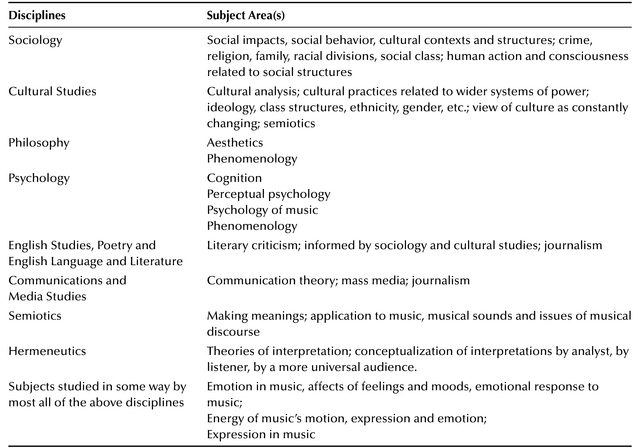

Scholars from numerous fields have examined popular music, exploring various factors both within and external to the song’s music and lyrics. Many of these studies emphasize either contextual or meaning matters, and some address both. Disciplines examine the record from their unique perspectives, often not engaging the actual substance within the song; perhaps understandably, such studies often focus on the issues within their discipline—disciplines such as sociology, social psychology, philosophy, literature or others. Other disciplines adapt existing theories or modify analytical methods that were originally designed to study different fields—such as semiotics, with its origins in linguistics. Together, this is a disparate group representing widely varied branches of knowledge. Table 1.1 provides a summary listing of these fields.

Table 1.1 Subject areas of popular music analysis outside the three domains of the record.

What follows is a brief coverage of the significant subject areas that might be incorporated into a recording analysis by appropriating their methodologies, should their perspectives and knowledge base align with the goals of the recording analysis. Within the following chapters several of these areas will be engaged in greater depth. An adequate presentation and examination of these subjects is beyond the scope of what can be included here—despite the value and richness offered by some of these fields. The intention here is to identify other, potential areas the reader might seek out for more detailed study, initiated by following source references. With this broadened study, the reader will determine which, if any, external disciplines might enrich their individual analyses.

Popular music makes deep connections with listeners, and stirs listeners in individual and collective ways. It reaches the visceral and the physical, speaks to the cultural and the social, the personal and the collective, it engages reason and mood, touches heart, mind and soul. It does all this to a wide and varied audience; a single recorded song might resonate deeply within millions of people. How, then, might analysis illuminate the ways this music both influences society and reflects it, and the means by which those associations and connections are made? How might an analysis examine the record as interpreted by the individual, by the analyst, or by a more universal audience? How might an analysis reveal the meaning of the lyrics, or recognize how the track’s sounds stir and move the listener?

This brings us to what might be of greatest interest to general readers (and music lovers of all types), and also to those of us fascinated with studying and creating recorded songs: an analysis can provide acknowledgement that the record reaches inside the listener. Our analysis might identify the source of what infuses the track with energy and brings it to penetrate into the bodies and psyches of listeners. We can explore how this track elicits the sensual, the disturbing, or the ecstatic—whatever the recorded song’s core character might be.

Sociology and Cultural Studies

Sociology was among the first disciplines to begin examining popular music below its surface. It is the study of human behaviour and society, how human action and consciousness are shaped by and shape social and cultural structures—including social class, race, gender, religion, crime and economics. The interrelationships between music and society (creating some social context for the analysis) are central to popular music. This is articulated by Ian MacDonald, who frames “the main feature” of his The People’s Music (2003, vii–viii):

Sociology’s methods can bring insight into the social impacts of records, their social context(s), and the social influences on records—to a genre or artist in general, or in relation to specific tracks. By incorporating this discipline into one’s approach, social meanings, influences and significance might formulate and emerge. Sociology is linked closely, perhaps symbiotically, with cultural studies. These two intersected fields largely informed music critics and music journalism, especially in the early years of popular music studies.

Cultural studies emerged from a confluence of various disciplines including (notably for our purposes) sociology, politics, media and communication studies, literary studies, geography and philosophy. It is a field engaged in critical analysis of cultural practices of cultural phenomena—particularly those related to power and control (especially political dynamics) often directed toward studies of ethnicity, gender, generation, nation issues, sexual orientation, ideology and class structures. Seeking meaning generated from analysis of social, political, economic realms, its critical approaches include diverse fields, including those pertinent to popular music analysis: semiotics, media theory, film/video studies, communication studies, literary theory. Keith Negus (1996, 4) defines the “general point” of his Popular Music in Theory “that music is created. Circulated, recognized and responded to according to a range of conceptual assumptions and analytical activities that are grounded in quite particular social relationships, political processes and cultural activities.”

Philosophy and Psychology

Philosophy has two branches of particular significance to records: aesthetics and phenomenology. Aesthetics is traditionally defined as the theory of beauty, perhaps together with the philosophy of art—or the study of beauty and preference. It is a large field at its fullest. Aesthetic concepts, aesthetic value, aesthetic judgements, blend with other topics that might be brought to task in interpreting and evaluating tracks. The aesthetics of music concentrated on art music until recently—this position articulated its placement at the top of the higher forms of music and its advanced modes of response. The aesthetics of popular music can be studied in great detail in its own right (Gracyk 1996). While some studies of music aesthetics are closer to sociologies of music, aesthetic concepts can provide insight into the record, and also appreciation for the record’s qualities. In a manner of blending these subjects, Simon Frith offers:

Phenomenology studies the subjective experience, subjective phenomena and structures of consciousness, especially the first-person perspective (a common perspective in song lyrics, but most importantly: the listener’s perspective). It studies how it is that humans are able to empathize with one another’s experiences, and find ways to communicate about them, by engaging the mechanism of ‘intersubjectivity.’6 Phenomenology asks one of the most vexing questions in analysis (especially important with an analysis based on sound alone): ‘Is my experience the same as yours?’ In doing so it seeks to recognize what is universal or generalizable across humans engaged in the same experience; these are the objective aspects of an experience despite the differences across human subjects. Thomas Clifton (1983, 38) explains phenomenology is “more interested in describing rather than proving or predicting.” Before extensive detailing of the manner of describing, he notes: “[D]escription of phenomena is something other than a blow-by-blow account of technical trivia . . . and also other than dreamy-eyed embellishments around a musical object pressed into the uncomfortable role of a narcotic.” For the interested analyst, applications of phenomenology might hold strong potential to define shared musical experiences, communication and meaning between humans and groups. Phenomenology straddles philosophy and psychology—some refer to this intersection as ‘phenomenological psychology.’

Psychology is a complex field, and is sub-divided into a natural science and a behavioural, human science. As a natural science it studies psychological phenomena as natural phenomena (tending toward biology and chemistry), and as a human science (behavioural) it accounts for experiential, social and cultural phenomena. For much of our use is in psychology’s study of aspects of the conscious and unconscious mind and thought, including the study of behaviour. Psychologists explore many concepts central to our work, including: perception, cognition, attention and emotion. Perception and cognition of sound, of language and of music (and of recording) are central to music listening and analysis processes. They are woven into the framework for recording analysis presented here, and are strongly represented within other recent approaches.7 Lawrence Zbikowski provides some insight into music cognition within his examination of a discussion of Robert Johnson’s 1936 “Cross Roads Blues”:

The psychology of music is concerned with the psychological processes involved in music listening, composing and performing music.8 Music psychology seeks to understand cognitive processes related to music and music behaviours of memory and attention (two central aspects of analysing music from records), in addition to perception and cognition. It can encompass emotion and meaning in music, as well as provide psychological analyses of perceptual, affective and social responses to music. We know music consistently elicits emotional responses in listeners, although it is a complex process and the nature of the affect is not consistent. Music psychology studies are helpful in examining this relationship between human affect and cognition (Sloboda 2005). This brings about interpretation as related to emotion and expression, as will be examined below. First we will look at interpretation related to meaning.

English Literature/Poetry Studies and Communications

Poetry and literature analysis and interpretation can be engaged to explore message, meanings and significance of and within song lyrics. While song lyrics vary considerably from ‘high’ poetry and literature in form and content, in their embrace of ordinary language (and defiance of correct grammar), and most importantly that they are written to be sung, they have received much attention from scholars and academic programs. Their analysis tools and methods can be usefully applied to the literary content of lyrics and the meanings of the lyrics, on various levels. Simon Frith demonstrates the potential of a sophisticated approach to lyrics as poetry as he explains Aidan Day’s description of Bob Dylan’s lyrics in Jokerman:

Of course, the lyrics of Nobel laureate Bob Dylan are not typical, and Day’s observations are particular to Dylan. The point here is this type of examination can be pertinent to the study of the track, and can shed light on the content, meaning, and artistry of the lyrics.

Communication studies is concerned with the processes of human communication—written, verbal and nonverbal. It is concerned with how messages are interpreted within the contexts of their political, cultural, economic, semiotic, hermeneutic and social dimensions, and as they appear within the full spectrum of platforms from face-to-face conversation to mass media outlets (i.e. radio, television), internet and social media. Media studies is often incorporated into the study of communications, with and without broadcast and technology-related dimensions (media editing and designing, on-air talent and acting, production roles and content authors, web design, etc.). Journalism is a central component of the mass communications discipline. Traditional journalism is based on objectivity, ethics and standards that give high importance to eliminating bias. Advocacy journalism has become increasingly prominent (facilitated by blogs and social media), and can project extreme bias without documenting sources; there is also tabloid journalism intent on unearthing the sensational, or writing fictitious accounts; and a more socially-oriented form of journalism characterized by less depth of substance, that is intended to peer into the lives and homes of the famous and the fortunate, and thus entertaining a curious public sector. Knowledge-based, researched journalism generating factual reporting of content and context can prove highly relevant to popular music studies—and the study of the record. This is in contrast to entertainment journalism’s infatuation with artists’ lives and intimate secrets, that at times includes personal matters of context relevant to the track (but often not); this accounting has been called “a fake idea of truth” (Griffiths 2004, ix) and is of little use in to understanding the record. Emerging from all these approaches is the ‘music journalist’; journalists who report on music and artists, review records, write analyses. At its best music journalism engages social commentary, the lyrics, or other fields, though even at its best it only rarely addresses the music itself;9 at its worst it represents superficial and sensationalized writings of little value to understanding the record.

Semiotics and Hermeneutics

As a discipline, semiotics is the study of meaning-making and meaningful communication; including the study of communication through symbols and sign processes, and the study of non-linguistic sign systems. This points to the state of having meaning outside or beyond itself—a situation that 'absolute' music avoids through its ‘abstract’ concepts and relationships. Semiotics as applied to music looks deeply into meaning-related aspects of music and musical sounds, a process particularly relevant for popular music. Philip Tagg (2013, 145) provides this explanation: “The semiotics of music, in the broadest sense of the term, deals with relations between the sounds we call musical and what those sounds signify to those producing and hearing the sounds in specific sociocultural contexts.” This begins his exhaustive coverage of the semiotics of popular music in Music’s Meanings; therein he formulates theories, typologies and analytic approaches for popular music through semiotics that may prove useful to some analysts and analyses. In describing the complexity of music and the challenges of writing about it, McClary and Walser (1990, 278) observe how sounds carry meaning and signification to create

Semiotics holds promise for the analyst to engage meaning in popular music, though the challenge is significant; the meanings of sounds are specific to social groups and contexts, therefore what is understood in one group may be understood as something entirely (or slightly) different in another. Cross-cultural or universally understood musical sounds and ‘codes’ are rare, and are mostly related to biological response to sound (Higgins 2012); aspects of music structure, musical functions and tension/ repose also “share far fewer common connections to extramusical phenomena from one culture to another” (Tagg 1987, 286). Further, the large number of highly varied genres of popular music and widely varied production tools and techniques expands the typology of sounds and sound qualities, and their associated meanings; defining a set of characteristics and their associative meanings is a task that will likely continue to be ever more complex as music evolves. Incorporating methodologies from cultural studies and sociology may lead to defining this issue of sociocultural connectivity to musical meanings solely for an analysis of an individual record.

Hermeneutics, in the classic sense, is the theory of interpretation; originally for text interpretation (mostly to sacred texts), it evolved to include methodology of general interpretation. Modern use includes both verbal and nonverbal communication, in many diverse fields. Hermeneutics is sometimes framed as ‘the art of interpretation.’ It has come to be applied to music, and is more of a central matter to popular music than to art music—although it does have some relevance to traditional music analysis.10 This makes sense when one remembers ‘serious’ music sought to be self contained, rational and objective, where it is not a central concern to question how music’s expression of moods and feelings affects the listener and shapes their relation to the world.

Interpretation exists at a number of critical points in the experience of the record (or a musical performance), and it is ultimately linked to meaning. Hermeneutics recognizes that what exists as the track (the record), is a limited expression of the artist’s view. Further, it recognizes the listener’s view also affects their understanding of the record. The artist’s view is more substantive than what is in the record; in other words, there is meaning in or behind the artistic statement of the record that has not been fully articulated. The listener’s cultural context of time and place, and their experience, education, expectations and state of mind contribute to their receptiveness to the artist’s view and influence their understanding. Here ‘artist’ is artists: lyricist, composer, arranger, performers, recordist, or producer; ‘listener’ is listeners: analyst, audience, or the individual listener. An important concept is the hermeneutic circle, which adopts the notion that as the whole is understood in reference to the individual, the individual can only be understood in reference to the whole; a circle between subject and object/event. Transferring the principle, the listener is constantly reassessing their conception of the record (the whole musical event), and with each reference (each new listening, or individual assessment of what has been heard) the interpretation is constantly being informed (and transformed, becoming more substantive or enriched) by the record itself.

Interpretation is inherently subjective, in all areas it is encountered or enacted. Recording analysis is itself an act of interpretation. Julian Horton (2001, 357) articulates this point: “[W]e never write the immediate, but an analytical strategy masquerading as immediacy,” a strategy (analytical process, approach, tool, or methodology) that is already influenced by our subjective position; in this way, an analysis is already influenced by the analyst’s predispositions and biases, as well as experiences and assumptions. From the others listed above, the interpretations of performers and others involved in the creative processes of creating and crafting the record are separate from our analysis concerns. In the application of hermeneutics to recording analysis we are concerned primarily with the receiver not the generators of the message—in other words, we are interested in the interpretations of the track itself, by the listener, or a more universal audience, or perhaps in the analyst. We might find ourselves in any of these three roles. In Song Means, Allan Moore articulates a methodology for Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song based on a “hermeneutic superstructure.” Moore (2012a, 1–2) explains the book is “about how they [recorded popular songs] mean, and the means by which they mean. . . . The reason I focus on the ‘how’ is that I believe that, as a listener, you participate fundamentally in the meanings that songs have.” Thus, he identifies meaning as being fundamentally linked to the listener.

The listener makes the meaning, not the speaker of the message (or the recorded song).11 It is the act of listening that transforms a stream of sounds into meaning—the listener interprets the sounds to arrive at meaning. As we have noticed, it is not isolated sounds that formulate meaning, but how they relate and what they represent, communicate, elicit, and much more.

Affects: Emotion, Energy, Expression

The understanding of how a track’s different elements come together and produce certain effects on the listener is distinct from those of interpretation or meaning. This sense of the expression, the energy and/or the emotive content of the record elicits response, reaction and sensation at the intersection of body and emotions. This might be conceptualized as the record’s poetics—following the notion of suggesting “poetic feeling, intuition and imagination.”12

Exploring, identifying and discussing what and how music emotes and what it communicates on kinaesthetic and visceral levels can quickly become highly personal and subjective—yet these are clearly part of the musical experience, a part clearly attractive to listeners. The highly personalized experiences and subjective interpretations might be the most important consideration of the lay listener, and may be perceived as highly significant by the beginning analyst—after all, we consider ourselves at least partially defined by the music we use, listen to, and the meanings we find in it. Allan Moore (2012a, 1) articulated this: “The chances are that who you believe yourself to be is partly founded on the music you use, what you listen to, what values it has for you, what meanings you find in it.” If our goal is a meaningful analysis that explains the listening experience (the track) beyond oneself—though, this is slippery ground. The personal can distort a productive collection and evaluation of information on the record, in contrast to a more detached process; the listener can become prone to seek information to validate or support subjective experience, rather than exploring deeply to discover more significant ideas. Passive and “pharmaceutical”13 (or mood modulating) listening instead of active and engaged listening may play a role in this type of perception.

To explain what makes the record work as a coherent communication (or how the recording shapes the record) requires some intentional steering away from the personal, away from the affective and emotional experiences of the individual and interpretations that are largely subjective—and toward the universal, to the objective aspects of an experience as perceived by one’s collective group of similar listeners who share some commonality of background, and to interpretations that are as objective as the human condition allows. This is not to imply listening experiences are less ‘significant’ during those times when listeners may (with or without intention) open themselves to the personal; this perspective is natural and common, and may well be deeply rewarding to the individual. This acknowledges such forms of understanding have strong potential to benefit only the individual, and have the potential to generate interpretations so highly personal they are shared by few others. To contrast, in seeking what may be the universal, one is more prepared to engage the unexpected or unknown and allow for the potential of any experience to be significant and to communicate uniquely (and in the realm required for analysis).

This is perilous territory to navigate. Most everyone talks around this, or addresses it in very vague terms. It is difficult (perhaps impossible) to generalize about personal experiences that hold deep meaning for listeners—individuals, groups, cultures, social clichés, etc. Emotion, energy, and expression will quickly tend to defy adequate description. The tools to engage these are few, and our vocabulary can quickly seem too much related to the senses than to analytical processes. Music has always defied verbalization to a considerable extent, and analysis can struggle for vocabulary and to bring concepts into language. Although music has a level of syntax, it lacks a consistent lexicon or semantics that can embrace or engage the many genres (‘languages’) across its breadth. Indeed, some believe it is simply not possible to adequately describe music, or the experience of music. Moore (2012b, 101) provides a response to this reluctance to engage what might be “always beyond precise verbalization,” by recognizing “to avoid the attempt is to render our evaluations worthless.”

Some of the above disciplines can provide access here. The ‘intersubjectivity’ and revealing meaning in semiotics (Tagg 2013, 195–228), hermeneutics’ guidance in formulating and conceptualizing interpretation, seeking the objective qualities in shared experience through phenomenology, the lyrics’ poetics and meaning engaged through literary methodologies, and exploring affect through the psychology (and sociology) of music all open different forms of access to this territory.

The questions to understand the record’s emotion, energy, and expression are perhaps simple to frame, but are vexing to solve. A start might be:

- How might we seek largely universal descriptions of ‘what provides energy’ to the tracks, and ‘what is the energy’ of the record, ‘what feelings, emotions, expressions are present,’ ‘what (by a quality, reference, an object, etc.) is it that elicits them,’ and ‘how (i.e. through an event or process) are they created?’

- What tools are of use to determine transfers of meaning and affect across groups (social, cultural, economic, etc.) of listeners?

- What is cultural, what is personal, what is biophysical within the qualities or meanings that are perceived?

Incorporating Other Disciplines Within an Analysis

These disciplines and subjects can be incorporated into the recording analysis in a myriad of ways. Many topics and disciplines might inform an analysis. In addition to those just described, the established research stream of sound studies might augment the context or meaning qualities of an analysis, and the recently emerged stream of ethnography can add dimension (related to context, interpretation or meaning) to the creative voice and process.

Ethnography has roots in ethnomusicology; it has been seen as an ‘urban ethnomusicology’ treating mediations and interactions as normal aspects of culture (Walser 2003, 18). Central to popular music studies is a stream of research examining studio-based ethnography.14 This stream sits at an intersection of a number of communications and social disciplines, with a degree of focus on ethnomusicology research interests and methodologies. Roughly, this is the study of the cultures, interactions of people (often power-related), creativity, technology influences, and the creative processes within the recording studio environment—or of recording processes, as might seem more appropriate. Though related to ethnomusicology, research is rarely focused on the record itself (the artefact of the recording process), but rather on the social, cultural, functional, anthropological (and so forth) aspects of recording studio practice in creating the record. The process can shape and impact the record in profound ways, and can enrich recording analysis at times; this emerging field examines these, and more.

Sound studies also sits at the intersection of many disciplines, with a focus that can shift depending on the subject of the study. Human impact on the acoustics of the world is at the core of this discipline. The range of disciplines includes ethnomusicology, acoustic ecology, nature, acoustics, psychoacoustics, perception, anthropology, philosophy, sociology, media and cultural studies, film studies, urban studies, architecture, arts, musicology, music theory, and performance studies. Sound studies concentrates on the history of audio media, the nature of sound and listening, and the roles of sound and listening within the modern experience. Sound scholars look at perception and the effects of sound, the ways humans interact with sound and how sound interacts with the world around it; some study change and reactivity. Some streams hold significance to recording analysis as they inform understanding of recording’s elements, their perception, and the human condition.15

As with incorporating other disciplines into an analysis, these interdisciplinary streams might be of interest to some analysts, and relevant to certain records, or enhance analytical methods; they can inform the analysis, but are not analytical tools. It bears reminding here: the record itself—the artifact that is the message, substance and content of the creative voice—is at the core of the analysis. Exploring and identifying the ways the recording shapes the track, and the track itself, are the central topics of recording analysis. Variables here are the goals of the analysis and the subjects the analyst wishes to illuminate, and the balance between the record itself and the outside subjects pertinent to understanding its content and message.16

Every record is unique and demands analytical techniques appropriate to it, and an analytic framework that is accepting, relevant and useful for the study of them all. The framework functions directly as a broad structure, inviting the analyst to apply their own questions and methods of inquiry within its process. Appropriate depth and breadth of coverage appropriate may be adjusted for the skill level of the analyst—from more general analyses to the meticulously detailed, graduate-level studies or a beginner’s exercise, work by a novice or an established scholar will all approach recording analysis with a different sense of purpose, a different skillset and their own desires, experiences and preferences. When to incorporate disciplines outside the domains, which to incorporate, and how to assimilate all perspectives and the information those subjects offer depends on the analyst. No single approach is promoted here; rather, what is proposed is a sense of what is possible, so the analyst can seek to identify what is important for the individual track, and steer the analysis to directly engage it.

The lucid analysis will clearly define the degree to which it engages these subject areas—and which to evaluate. To be relevant, any conclusions generated from these areas will relate to the substance and sounds of the track. The content of the individual song will play a role here; for example, a song with expressed social views will be examined differently than one with materials and sounds that make connections with dance and romance. A number of these disciplines can generate studies in themselves— they can inform our analysis of the record, or they may stand alone.

Advocates for any one or particular combinations of these subjects will note their approaches are indispensable for the understanding of the track. They would be right, both from their vantage point and also for the completeness of an analysis (which might demonstrate what is relevant to the track, and what is not). This brings us to a need to recognize the content of the individual analysis is not only what it seeks to do, to discover, to evaluate and to understand, but also what it chooses to omit from detailed or direct consideration, or even from superficial acknowledgement. A lucid analysis will define its coverage within the track’s domains, and those outside—and to what purpose—to best serve the individual record.

FRAMEWORK AND PROCESS

An approach to recording analysis is offered here, directed to the recordist as well as the analyst. This approach is intended as a framework and a flexible, functional process. It is intended to be practical and accessible, and intended to lead one to explore the contributions of the recording to the track. These contributions may include its materials, relationships, concepts, characteristics, expression, and more. The framework does not prescribe a methodology, a set of instructions, a philosophical or aesthetic basis, nor a theoretical premise. Rather, the framework establishes a point of reference and departure for a process of exploration—a process that is adaptable to the individual record, a process guided by inquiry into the record itself, beginning with the recorded song itself, a process based on a framework of a few simple and direct principles and concepts.

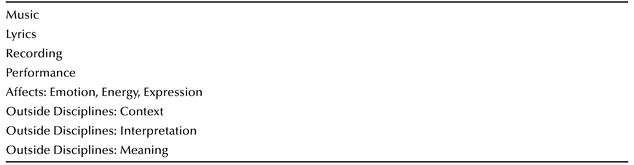

Table 1.2 Subjects that might be incorporated into a recording analysis.

This approach is designed to guide readers to perceive and collect information with an intention of objectivity and accuracy. It offers direction for the evaluation of information to identify the defining qualities of the individual work; to arrive at conclusions of relevance and significance for the track studied. The framework establishes a general scheme of inquiry from which the process may forge or explore many paths—paths that are unique and appropriate for the individual recorded song—so pertinent conclusions may emerge.

This is a malleable, broad framework that does not define how it is to be used; one within which methods of examination appropriate to the individual record might be applied (or emerge) and function.17 The process of the framework can incorporate or be adaptable to most theories or methodologies related to the analysis of popular music or the analysis of songs (and records). No single approach, theoretical construct or analytical methodology, can be the most effective portal for the study of all recorded songs. Nor might any meet the needs of all the goals one might have in analyzing a track— including embracing streams of knowledge outside the sonic content of the record. Therefore, the most appropriate approach and the most appropriate analytic tools are determined independently— and these can only be identified once within the process, once some pertinent information about the record has been uncovered. Within the process of recording analysis, the analyst will be required to determine the method(s) most appropriate. The recorded song itself will reveal the methods required to access its character and message.

With but a few important exceptions, existing methodologies do not examine the qualities of the recording, or the influences of the recording on the recorded song.18 Rather, most approaches are focused elsewhere—be it aspects of the music, the message or meaning of the lyrics, circumstances around the track, social or personal interpretation, stories surrounding the artist(s), and other areas.

Herein may be the beginnings of a methodology for examining the qualities of the recording, which might supplement those analytical methods that cannot otherwise address the recording. Some unique approaches to the elements of recordings are offered, and are important aspects of this approach to recording analysis. The elements of recordings are defined and explained, and the reader will be guided in learning how to recognize the subtleties of their qualities. Tools for evaluating their characteristics and activities have been devised, including an approach to a vocabulary for describing their qualities. Their contributions to the record are explored, and will be central aspects of the framework.

Framework's Analysis Sequence

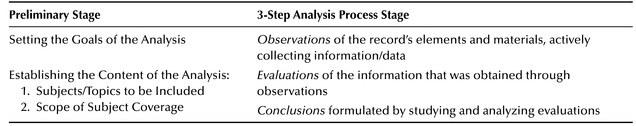

The framework’s analysis sequence has two stages: a preliminary, preparatory stage and a stage encompassing the three-step analysis process.

Table 1.3 The framework’s two-stage analysis sequence.

The preliminary stage sets the goals of the analysis and establishes parameters for its content. The goal of the analysis identifies the purpose of the analysis, what it wishes to learn about the track. Establishing content articulates the subjects or areas that will be the focus (topics of study) of the analysis and the scope of coverage (its breadth, level of detail, etc.) each subject will receive. The topics to be explored, the object(s) of study, problems to be solved, tasks to perform, etc., are established. Domains to be examined or emphasized, outside disciplines to be included, specific traits to examine, and much more are embraced within the goal, focus and scope of the analysis. One can expect focus and scope to evolve during the course of studying the track—some subjects outside the record may be added, some subjects deemed uninteresting and discarded, some topics emphasized, some areas minimized, and so forth—though the goals will typically not change, but will likely be refined. As one learns more about the record, one recognizes what warrants further study or greater detail, how inquiry needs to expand or focus, and what one needs to uncover. This sense of scope and focus allows the process to unfold productively and with a sense of purpose that is defined and guided by the goals of the analysis.

At its simplest, the three-step analysis process follows the path:

- Observations of the record’s elements and materials, and outside disciplines and sources;

- Evaluations of the information obtained through observations;

- Conclusions derived through study and analysis of evaluations, etc.

This general three-stage process has some similarity to traditional style analysis,19 and some distinct differences. The process is designed to function fluidly for recording analysis; it can flex to embrace typical structure-oriented processes and style analysis approaches, and will open to other approaches as well—especially those that might be devised by an analyst to best serve the track being examined. The process is malleable and is general enough to remain consistent from one analysis to the next. One might pursue any level of detail at each stage—adapting to various skill levels, the purpose or goal(s) of the analysis, or the needs of the individual recorded song.

The observations stage is simple data collection of ‘what is there’ within the recording, within the lyrics and within the music. Any method that does not bring evaluation in to play might be utilized (at one’s considered choice) in order to collect this information on elements and materials. The important matter is to collect information before interpreting or evaluating the information—limiting confirmation bias as much as might be possible.20 This minimizes the influence that evaluating information might have on collecting information; when one begins to sense organization or content, one can involuntarily begin to perceive ‘what is there’ as ‘what I have found’ based on ‘what I wish to find,’—or believe is there, or what I perceive as being present based on limited experience or on insufficient exposure to the materials. Some overlap of observation and evaluation is inevitable, as observations continue within the analysis process as one continues to discover each time one engages the record; the point is to delay evaluation and conclusions until sufficient information on the track has been collected so it can speak for itself. Thoughtfully sequencing this ‘data collection’ might help here; when one is inclined to make assessments of, say, the sonic characteristics of the text perhaps one might, instead, collect data on the melody that presents it, or the dynamic shaping of the line, or the interpersonal distance of the vocalist to the listener. This might seem a diversion, yet in practice is productive and informative, and will perhaps bring light toward identifying qualities that might otherwise go unnoticed. Observations originating in the materials and methods of other disciplines might be included here.

Within the evaluations stage various analytical theories and methodologies might be applied to examine the syntax of each element and the formulation of materials, to identify functions and to determine the relationships of materials, and much more. Formal theories and specific methods are not the concern here; rather, the focus is on revealing the content of the record.

At the ‘conclusions’ stage, the definitions of theories and methodologies might take more precedence, as per the position of the analysis. This stage is the broadest, most complex and most individualized by the analyst and/or conforming to the requirements of the track. The multidimensional interactions of all elements, and all materials of the three domains are examined, considered and insights formulated, tested and finalized. Here is where connections and discoveries are made, information synthesized, and where the analysis is collated and formulated. The goals and breadth of the individual analysis might include a careful examination—perhaps a central examination—of social context and impact, semiotics and interpretations, and expressive qualities and meanings, in addition to the three domains. The complex confluence that embodies the individual record is deciphered and revealed here.

Framework Principles and Concepts

As the framework seeks to be conceptually simple, it is guided by a few basic principles and concepts. These are principles that provide context for the framework, and concepts that provide points of reference for recording analysis. While the framework embraces these and allows them to provide a sense of guidance and coherence, this is not a methodology, but rather a simple approach that establishes a ‘frame of mind’ for freely and deeply exploring the record. It is deliberately nondescript in analytic method, and it intentionally avoids any one purpose or goal of analysis.

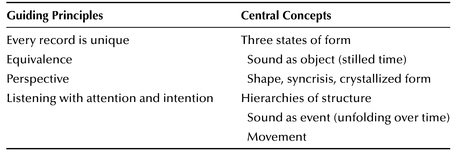

These principles guide the process, while seeking to be transparent in their influence on any outcomes. By these few principles the framework seeks to be open to information of all sorts, with a minimum of bias from past experience and knowledge. The framework seeks to impose limited influence on the analysis process and on what is revealed. The four principles are:

A primary position (principle) of this writing, and of its framework, is that every recorded song is unique. This might at once sound obvious, perhaps even trivial. The premise is quite radical, though, if considered in light of how often widely accepted analytical methods can bring vastly diverse pieces of music to look the same, or very similar, once they are analysed. Methods of analysis may easily function as “the equivalent of a sausage machine: whatever goes in comes out neatly packaged and looking just the same” (Cook 1987, 2). An analytical method might be applied with the intention of illuminating the work, but instead the work is forced into one of the few predetermined, model structures the method makes available. Analytic methodologies can thereby limit investigation of the individual piece; an examination with few options limits the opportunity for unique qualities to emerge, be recognized. The analysis might validate the theory (however loosely), but does not provide insight into the work. Fully embracing the notion that every recorded song is unique is indeed radical, then, as it throws conventions aside and opens one to the possibility of something new in each record, the possibility of something new that might embody each track. Each record is a world unto itself, and this position allows this world to be most fully explored. To recognize the uniqueness of the individual recorded song is one of the guiding principles here; it will be realized most accurately utilizing a process capable of revealing the record’s unique materials and qualities.

The second guiding principle is that all elements are of equal value, and have an equal potential to be significant, to be used as a basic element in a musical idea (Tenney 1986, 8), and to shape the message and the artistry of the recorded song. This is the principle of equivalence that identifies any element of any of the three domains has an equal potential to contribute to the uniqueness of the recording at any moment, and at any individual level of the multidimensional texture of the recorded song—this includes the elements of the recording. This provides the opportunity whereby pitch, for example, is not necessarily more significant that any other quality or element; that the music or the text may not be more significant than the recording. ‘Significant’ here does not mean most important, primary or prominent; significant means that the element plays a crucial or substantive role. This principle is central to many stages of the analysis process, as well as to the listening process; it is integral to discovering the unique qualities of any record.

Perspective is the third guiding principle; it represents the act of observing and engaging specific level of detail. Perspective might be conceived as occupying a particular vantage point, or position of observation. Knowing one’s perspective as a listener, allows clarity of what information is being observed and at what level of detail is the focus of one’s attention. Perspective allows one to make marked shifts during observations and evaluations; for example, it might establish awareness to the activity on a specific structural level, or might focus attention within a sound’s timbre. This principle embraces and acknowledges the multidimensionality of the record, and provides guidance in navigating its conceptual levels; it makes comparisons within the same level or across levels possible. Perspective assists in articulating intention and focus to the listening process, and it lends clarity to the analysis process of engaging specific structural strata, and their elements and materials—and much more.

Listening with attention and intention is the fourth guiding principle. Listening is the only way to access the record. The deep listening needed to access the workings, materials, messages and affects of the record requires an engaged and deliberate listening process. Directed attention is contrasted with open awareness; these are guided by intention in alternate listening experiences. Within the intention of listening a balance is sought alternating between seeking specific information and observing the sonic profiles of the record for what is significant and of interest. Attention holds the perspective intact, without intention perceptually salient features will grab attention and divert or distort the listening experience. Evaluating all dimensions of the record is facilitated through approaching listening with intention, and systematically holding focused attention throughout the experience. These concepts shape the process of collecting information from the listening experience and they shape the quality of the experience. This is not to say one cannot listen openly, seeking notable features that grab attention naturally; the analysis process requires hearings of this sort. One can establish a context of open listening, of being receptive to the unknown, of being prepared to hear the unexpected.21 It is being open to the unknown and being receptive to the unexpected that allows discovery of the uniqueness of a record.

Interrelated to these principles, the framework divides form and structure into separate and distinct concepts. The two are distinguished by characteristics of time, dimension and other inherent qualities. Table 1.4 outlines the guiding principles and the general form and structure concepts of the framework. The concepts of form and structure will be explored in detail in the next chapter.

Table 1.4 Guiding principles and central concepts of framework.

In conclusion, within this framework, any viable approach to analyzing the disciplines and domains of the recorded song might play out and reach its goals—if, of course, utilized with adequate skill. Methods of analysis and focused objectives many be used singly or in combination to best illuminate the unique record. Robert Walser (2003, 24) articulates this as he identifies that the success of an analysis “is relative to its goals, which analysts should feel obliged to make clear.” Clarity within an analysis is formulated through clearly defined goals of subjects and disciplines to be examined, and success in illuminating the track is achieved through defining goals appropriate to the individual record.

CLOSING THOUGHTS ON ANALYSIS

This recording analysis framework and process, with its guiding principles and concepts, will facilitate controlled exploration and open discovery by not being tied to formal methodologies or theories. Controlled exploration and open discovery are essential for an analysis of a recording, and each present their own challenges. A suitable balance of the two is sought—a balance determined as much by the skill level of the analyst as it is by what is appropriate for the analysis. Later chapters will suggest ways of engaging and balancing these. When options are many, the processes to choose, to limit, to focus, to define gain significance—this becomes part of the process itself. Walser (ibid.) offers: