Chapter 4

Domain of Lyrics: The Voice of the Song

This chapter examines the domain of lyrics.1 An understanding of the content of lyrics (its structure, story and sounds), and how lyrics are transformed in performance (connections with melody, vocal qualities, intelligibility, style, etc.) will open one to a deeper recognition of the ways the record shapes the song. The recording can significantly shape the sounds, meanings and impressions of the performed lyrics; these will be introduced here, as an introduction to what will be presented in considerable detail later. This chapter seeks to set a context for engaging lyrics, and to define some fundamental concepts; it is far from an exhaustive study of song lyrics.

This chapter might seem incomplete to some readers. Established methodologies and approaches to examining the content of the lyrics are noticeably absent in this chapter. Further, there has been no coverage of how the lyrics are situated in culture, and the host of ancillary concerns. Many of the numerous disciplines introduced in Chapter 1 might be included in the examination of song lyrics. In fact, many of these disciplines have research methodologies that have been used in examining popular music, and some resulting important literature in this field. Lyrics may be studied from the vantage point of poetry and verse, literature and literary criticism, sociology and cultural studies, psychology and philosophy, and innumerable other disciplines and sub-disciplines. The strengths of each have been used to examine the lyrics, to attempt to study the social forces that produced them, and for a diversity of purposes. The reader is encouraged to engage those disciplines directly, from within their specializations.

The goals of an individual recording analysis may bring significantly different types of emphasis to the lyrics. The flexibility of the framework can be applied for different analytic purposes with lyrics, just as it can for other areas. Deconstructing the materials and interrelationships of music and lyrics may be central to some analyses, and the recording and lyrics central to others; in some analyses these may be more of a peripheral consideration, and some analyses might steer clear of lyrics entirely. The performance of the lyrics is shaped by the singer’s sound and style, and by the content of the lyrics; the recording captures and can enhance the performance. Social, cultural, philosophical and many other connections can emerge from lyrics, and be rightly incorporated into an analysis—as can the lyrics’affects. The unique qualities of the individual track reflect these. Again, the recorded song itself will determine how it might be most effectively examined—lyrics and vocal performance included.

The role of the song’s lyrics immediately seems clear, and mostly obvious. Lyrics speak to the listener; communicate the message or the story of the song. Yet there is more to lyrics; song lyrics are performed, and the performance is part of the communication. The singer not only communicates the lyrics, the singer also communicates through the lyrics. Lyrics reveal the persona and narrative of the singer’s dramatic role, and more. These become apparent in the contrast between performances of “All Along the Watchtower,” the original by Bob Dylan (1967) and the cover by Jimi Hendrix (1968). Meaning and story, ideas and emotions, word sounds and rhythms, listener memories and associations, listener interpretation and countless more, all blend into the expression and message that is heard.

This message can be direct and simple, with all that is intended clear to the listener—evident in many early Beatles songs such as “I Want to Hold Your Hand” (1963). As found in many songs, messages can be complex in content, containing layers of meaning encrypted in a maze of inter-textual references, symbolism and metaphors; all to some extent subjective, perhaps highly inter-subjective. Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” (1984) communicates directly through some of these devices and in layers of meanings. In each of these, the singer’s voice might express a singular thought and emotion, then move quickly between various states of feeling, all the while expressing different views of the subject, and providing the listener with “not only comprehension, but comprehension accompanied by felt experience” (Oliver 1998, ix).

The message of the song is imbedded in the text. Message and its meanings are revealed as the structure’s organization unfolds; the lyrics’ language and poetic devices shape its content, word meanings, pacing, rhythms, rhymes and sound qualities. The text is further enriched by its delivery. The singer provides voice to the song, through their persona and their performance of the lyrics; their “recorded form embodies both singer and persona” (Lefford 2014, 56). Added expression and sound qualities enhance meaning, shape the message, and enrich the felt experience.

The voice of the song is manifest through the lyrics and in the singer’s performance. This holds whether or not the lyrics are accurately heard, understood, or the focus of listener attention. The message may be delivered regardless of whether the words are intelligible in performance or in the recording. The text does not need to be understood for the persona’s attitude and character to be recognized; the voice projects intensity and sound qualities as no other instrument can, and also exhibits the image and dramatic presentation of the main character. The human voice attracts attention above all other sounds, and in unique ways. “Pop songs celebrate not the articulate, but the inarticulate, and the evaluation of pop singers depends not on words but on sounds – on the noises around the words. In daily life, the most directly intense statements of feeling involve just such noises: people gasp, moan, laugh, cry, . . .” (Frith 1983, 35).

Acknowledging this, we will start discussion from the position of seeking to understand the literary and poetic content of lyrics. Following, we will examine how the lyrics are presented and are often enhanced in performance. The last section offers a cursory view of ways the recording brings drama and dimension to performed lyrics; this material will be explored again in Chapter 10. All this will be undertaken knowing at times the lyrics may not be understood by a listener, and may be misunderstood, or may contain few intelligible words and communicate little actual verbal meaning. The information on lyrics is related to:

- Message and meaning in the song

- Themes and stories, subjects and ideas

- Structure of the lyrics

- Contributions of poetic devices and references to outside sources

- Sound elements of the text (timbre, rhythm, pitch and dynamic inflections)

- Delivery of the lyrics

- Paralanguage and nonverbal vocal sounds

Since there has been song, music and lyrics have complemented one another. In interacting, bending to reinforce the other, contributing their individual unique qualities, and fusing into one, they create something much different and richer than what each represent separately. In the song, many expressive and communicative qualities emerge through the innumerable materials and interactions of lyrics and music—and from their performance.

The interaction of the song’s sung melodic materials with lyrics is crucial to the song’s overall character and message. A multitude of other characteristics are generated from the song’s sung text (in all its dimensions) within its musical setting (and its many elements). The song is a message or a story on a musical journey—its lyrics elevated, enriched or expanded by its musical context.

It is deeply apparent: the song contains much beyond its music. The recorded song—the record—is richer still. A glimpse of the interactions between the record and the lyrics will follow.

In engaging lyrics and the voice of the song, the analyst is drawn to question the contributions of the lyrics to the recorded song. Contributions that are sonic (rhythmic, dynamic, timbral), structurally related to sound and to ideas, concepts, drama, and more are potentially relevant. In this examination, an appropriate guiding question might be: How do the lyrics communicate by their substance and expression, and perhaps what they communicate—though ‘what’ lyrics communicate is (as we shall learn), in the end, our own interpretation.

LYRICS: MESSAGE, STORY AND STRUCTURE

Song lyrics often have some similarity to poetry. Both utilize a robust sense of language, and seek to engage the reader/listener on both emotional and intellectual levels. Many song lyrics carry strong traits of lyric or metered poetry, some only hints; other lyrics are more like prose. Dai Griffiths (2003, 42) recommends: “first and crucially, that we stop thinking that the words of pop songs are poems, and begin to say that they are like poetry, in some ways, and that by extension if they are not like poetry then they tend towards being like prose.” Perhaps some greater clarity of the qualities of song lyrics might emerge with a comparison to poetry, whereby we might seek the “borderlines which can and do become blurred” (ibid.) between the two.

Allan Moore (2012a, 113) offers: “Although lyrics are not poetry, and the two categories of expression should not be confused, some technical poetic devices can be found in lyrics, and can add a certain expressive quality.” The guiding concepts and principles of poetry, and poetic devices of all sorts, might provide a ‘point of reference’ whereby one might identify how a song’s lyrics ‘do and do not’ conform, to better observe and identify their qualities. Some of the terms and concepts used here, as we explore this connection, will reflect those of literature, and some will be unique to song lyrics.

The theme and subjects of poetry are often more abstract and complex than song lyrics, though this is certainly not always true. Song lyrics may have a strong message, tone or theme, but this is not necessary; they may have a story to tell, or song lyrics might convey little substance. Lyrics have the support of the musical setting to help communicate its theme and subject matter; some song lyrics do not communicate as well without music. Poetry speaks by itself; it stands on its own content to deliver its message and ideas. Poems are written knowing the reader may stop and reread sections as desired. Readers can study poems; they can look up terms and explore imagery and ideas, and more. Poems can be examined deeply outside real time.

Conversely, song lyrics must speak to the listener immediately. Some lyrics will yield a depth and complexity to reward additional listening, study or thought, though this is often not the case. Song lyrics must also quickly capture the listener’s attention in order to inspire their further engagement. Song lyrics pass in real time, incorporated into the performance of the track. Listener engagement and communication of message are often the function of the lyrics’ chorus or refrain; there the song’s idea coalesces, exemplified as a line from the Rolling Stones’ song that is also its title: “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” (1965).

Both lyrics and poetry are structured, incorporating word sounds and rhyming; poetics are often found in song lyrics, as well as point-of-view perspectives and tone. In contrast, the structure of song lyrics typically establishes a recognizable departure from literary poetry. Poetry can be of any length and structure, while song lyrics tend to be concise, efficient in their use of language. The prominence of recurring phrases, topics, words, sounds and rhythms of many song lyrics are simply out of place in the context of many forms of poetry. Further, song lyrics integrate into and/or complement the rhythm and structure of the music. Though some poems benefit from being recited, most can be read silently and be successful; lyrics are intended to be sung—they are conceived as sound events.

Structure of Lyrics

Many lyrics may share certain traits with metered poetry. Similarities can be visually apparent in looking at the layout of structure, as song lyrics are often clearly divided into stanzas, just as poetry. The first stanza in metrical poetry establishes an initial design of lines; the design is comprised of a recurring metrical pattern, a line length or lengths, and a rhyme scheme, or system of rhyme. This likewise is common within song sections.

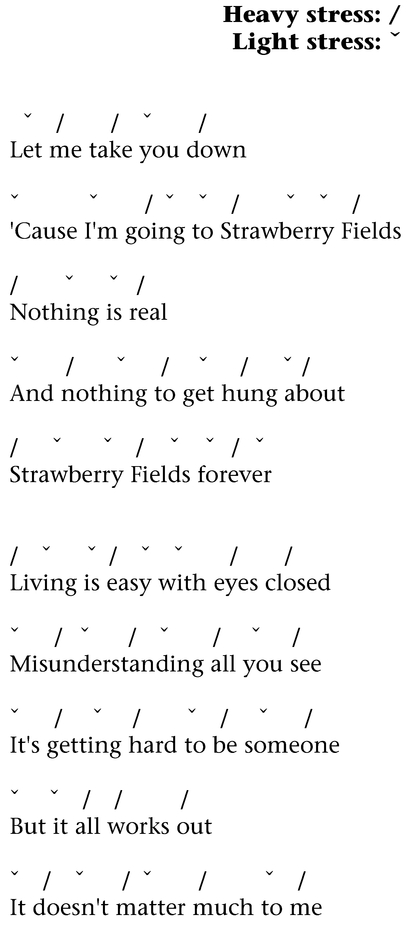

Lines within the stanza have rhythm. Within the lines there exist metrical patterns, called feet. A foot is either two or three syllables in length, organized in patterns of two or three light and strong stresses. Scansions notate the metrical pattern of a poem, and can be applied to lyrics. The notation accounts for each syllable of every word. Syllables receive heavy or light stresses within meters; these are marked by strokes on heavy stress syllables and by curves on those that receive light stress (see Figure 4.1). A recurring metrical pattern is established as the feet are repeated within each line. The metric patterns of the feet generate a recurring rhythm that is similar to music’s metric organization based on the measure—a metric grid for the poem. (Oliver 1998, 7–28)

Scansions reveal prevailing patterns and their variations of meter within the poems by reading the line as naturally as possible. The meter of spoken text does not necessarily need to align with the meter of the music, though. The stresses of spoken or recited lyrics may appear differently within the performances of song lyrics—the stresses of the melodic line, musical expression, meter of the music, dialect, and so forth, may bring heavy or light stresses to syllables that differ from what would be heard in a reading of the line. This brings us to recognize, there is a subjective component of interpretation involved in determining these patterns; this is especially prominent when no strict metrical pattern has been established—such as in “Strawberry Fields Forever” (1967).

Figure 4.1 presents the scansion from the chorus and first verse of “Strawberry Fields Forever.”2 Each of these stanzas has five lines. The opening chorus presents the two two-syllable feet (light+heavy and heavy+light) throughout. Exceptions to the two-syllable feet are the lines containing “Strawberry Fields” and “nothing is real.” Thus, a metric connection is made between them, which also links their content. The number of heavy stresses per line varies: lines one, two and five contain three heavy stresses, line three disrupts this pattern with two heavy stresses (omitting one heavy stress similarly to the fourth line of verse one), and the fourth line has a rather unusual heavy stress on the final “a-bout” which brings the line to contain four heavy stresses. Also within that fourth line, the words “to get” are an example of stresses that differ between the spoken word and the sung; speech would emphasize “get,” but Lennon sings “to” with the heavy stress.

All lines of the chorus end on a heavy stress, except the last; the word “forever” ends on a light stress, and the final line remains without closure (both metrically and philosophically)—forever. This is significant because it leaves the line and the chorus open-ended, aligning with the meaning of the line—structure and function supporting each other. There being no true rhymes in this stanza (the song’s chorus) also resists closure and emphasizes openness.

The verse (second stanza) presents a fairly regular four-beat line (one that is close to iambic pentameter) with the exception of the fourth line, though its stresses and syllables are somewhat elaborate. The many heavy stresses and syllables of the first three lines give them a meditative quality. In general, in poetry the more stresses there are, the more thoughtfully complex and reflective the line seems to become. The word “someone” at the end of the third line is rather difficult to interpret; it may be heard by some as a heavy stress on each syllable (giving the line five heavy stresses) or a light stress followed by a heavy stress (as notated in Figure 4.1), with the last syllable slightly more substantial than the first. The line “It all works out” contains three-beats of heavy stress amid the four-beat lines; this disrupts the meter of the verse, and gives a sense that something is missing; it also is less thoughtful, and though rather thrown out it makes an impact among the other lines that are more complex in meter and content. A pattern of light+heavy dominates all but the first line, which contains a rather floating (“living is easy”) impression from its heavy+light+light pattern that repeats until the line’s final word (“closed”) stops this patterning. The final line creates a sense of closure; it does this from its very regular four-beat light+heavy stress pattern, and from its rhyme—the only rhyme in these two stanzas, and the first rhyme of the song. These combine to make a strong sense of closure to both the line and the stanza.

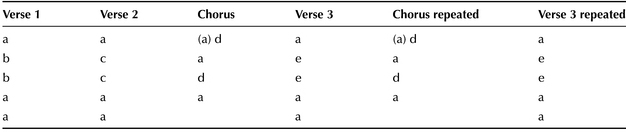

Recurring metrical patterns typically dominate flow throughout a poem, as they often do in song lyrics. Though flow might be interrupted from time to time, and a different dominant meter may exist in different sections, an underlying flow and patterning serves as a reference. A prevailing metric pattern is commonly established that is similar conceptually to the prevailing time unit in music; though much more prone to disruption, it is a reference against which we are inherently aware of variation. In “Strawberry Fields Forever” we see patterns shift regularly, though an underlying pulse is discernible. The patterning of “Here Comes the Sun” (1969), once established, shifts much less. The number of feet per line is part of the structural patterning of the poem. Line length functions to organize the syllables of the line into a meter for the poem. Patterns of line lengths establish another layering of structure within the stanza. Notice the patterns of line lengths of “Here Comes the Sun” as shown in Table 4.5.

The four-line stanza quatrain is a common stanza length and line structure. Quatrain stanzas allow a variety of end-rhyme patterns. This stanza may have one pair of rhyming lines and one non-rhyming pair (abcb), or two rhyming pairs of lines (abab). Any number of other rhyme schemes combining the four lines are possible: (abba), (abac), (aabb), (abcc), and so on. Rhyme systems need not be this simple. Internal rhymes allow words within lines to connect with line endings, thus connecting words at different points in line and stanza rhythms. Off rhymes (or slant rhymes) are words that do not rhyme exactly; these bring a different sense of connection to words, sounds, and ideas. Examples of these devices in song lyrics are very common. While all these rhyme schemes may be formalized in metric poetry, they often appear with considerable flexibility in song lyrics.

Figure 4.1 Scansion notating the chorus and first verse of the Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever” (1967). © 1967 Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC.

Turning to the structure of typical song lyrics, the similarities with metric poetry may be readily apparent. In most songs, text stanzas are comprised of a fixed number of lines in each repetition of the same section; the lines will similarly have fixed lengths, an established meter will be present, and a recurring rhyme scheme is common. Stanzas establish regular divisions of the lyrics. Stanza lengths and their line patterns (number of lines and number of syllables within lines) tend to repeat. Deviations from these line lengths and line sequences are notable departures that tend to be noticeable in their disruption of patterning. Contrasting stanzas are common in song lyrics—as verses and choruses are regularly at least slightly different in structure. Structural devices are commonly employed and alter metric, rhythmic or line length patterns in some way.3

Woven into these stanzas may be regularly repeated sections. These may work on a number of structural levels—a phrase, a group of lines, or a complete stanza. Some will represent refrains. Other repeated lines or sections might also be the song’s hook and/or repetitions of the line containing the song title; these anchor together the lyrics and music, and contribute significantly to song structure. The line and song title “If not for you” provides such an anchor in Bob Dylan’s song. The song title is the first line of each stanza and it is also the last line in each stanza—the first chorus is the single exception, using the word “true.”

Table 4.1 Structural components, patterns and relationships within lyrics.

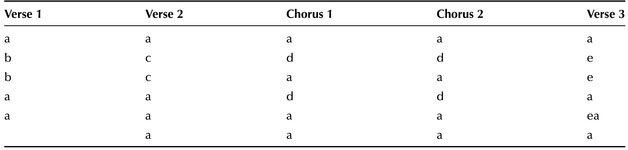

Table 4.2 Rhyme scheme of “If Not for You” by Bob Dylan from New Morning (1970).

Table 4.3 Rhyme scheme of George Harrison’s cover of “If Not for You” from All Things Must Pass (1970).

The rhyme scheme of “If Not for You” (1970)4 by Bob Dylan (2016, 257) illustrates connectivity between the song’s verses and chorus. The sections all begin and end with the same rhyme; verses all end with the song’s title—a recurring line throughout the song—except section. The fifth line of the third verse ends with “rings true”; the line rhymes with the first line of the stanza, while the word “rings” rhymes with the second and third lines.

George Harrison covered “If Not for You” on All Things Must Pass (1970). He adapted the verses to follow Dylan’s first verse phrasing and rhyme scheme, modifying the lyrics of verses two and three slightly to create the pattern of the first verse. Through his performance, Harrison runs the first two lines of Dylan’s chorus into a single line, and thus shifts the rhyme scheme; as he also modifies the last line of the chorus, the phrase structure is now a more traditional four-line stanza, that contrasts with the five-line verse. Harrison’s structure is a more typical rhyme scheme and phrasing; further, he separates the presentations of the two choruses by the third verse, and repeats the third verse at the end. Dylan’s version disrupts or suspends typical phrase rhythms and rhyme patterns, especially in the fourth and fifth lines of the verses and the chorus. Here we can clearly observe Dylan’s ability to shape the structure of lyrics in unusual ways, bringing unusual qualities and variety to both lyrics and phrasings; this is in striking contrast with Harrison’s version that distils the song into a more common structure, and with lyric pacing that is also more readily anticipated by the listener.

Sting’s “Fields of Gold” (1993) represents a somewhat typical quatrain patterning of stanza lengths and line patterns; each stanza is four lines, deviations are very slight and are the result of repeating the last line (the middle eight is five lines with its last line is repeated, the final stanza is six lines with its last line is repeated twice). In terms of structure and content, though, the lyric is uncommon; its refrains are embedded within the verses. No rhyme scheme is evident within the stanzas, though a distinct patterning of line lengths is present. The recurring images of barley and of fields of gold anchor structure; these occupy the second and fourth lines of each stanza (except for the middle eight) and provide the character of a refrain. The first and third lines resemble an unfolding of story; through them time shifts and romance evolves, children run and seasons change; though these lines comprise only half of every verse these present the bulk of the song’s action.

It is not unusual for repeated phrases or words, syllables or word sounds to contribute to structural coherence. These might establish end or internal rhyme schemes. Though repetitions of words or sounds may function independently from a stanza’s established structure, they most often bring coherence to lyrics. Even lines, phrases or sections comprised of nonsense syllables work in this way—as in the coda of “Hey Jude” (1968).

Table 4.4 Sound elements of lyrics, and word sound devices.

Timbre, rhythm and tonal inflection of lines, words and syllables all contribute to the character and the sound quality of the lyrics. This may reach beyond message, often touching into the realms of the visceral or the aesthetic; still, a connection to the human voice will remain. Word play between characteristics of the words and other sonic elements commonly appears, and expression can be enriched or transformed; the sounds themselves are often manipulated in performance, potentially establishing patterning of word sounds. “The Boy in the Bubble” (1986) by Paul Simon exemplifies word play, shifting word meaning (meaning play), repetitive word sounds and more; much is packed within this short excerpt from one stanza: “It’s a turn-around jump shot/It’s everybody jump start . . . Medicine is magical and magical is art/The boy in the bubble/And the baby with the baboon heart.”5 Contrasting with patterning of conceptual ideas into “rhythms of verbal images” (Bradby and Torode 2000, 223), or a type of ‘image play,’ discussed below.

It is common practice for sections of lyrics and sections of the music to coincide, though “lyric structures do not necessarily correlate with musical structures” (Middleton 1990, 238). Griffiths (2000, 197) provides a clear example of rhyme scheme in opposition with melodic structure found in “The River” (1980) by Bruce Springsteen: “The rhyme scheme is aabb: across it the melodic structure cuts chiastically, ABBA.”

Song structures typically move through sequences of verse/chorus combinations of various sorts— perhaps broken by repetitions of either section, or by inserting a middle eight or bridge. These stanzas might form patterns establishing units larger than the sequence of individual stanzas of verse and chorus materials—an example grouping verses and choruses appears in “Here Comes the Sun,” Table 4.5. Its verse+chorus patterning emerges when one recognizes the first chorus is linked to the introduction and the final chorus is linked with the coda; between these are three verse+chorus pairings, with a ‘middle section’ interjected between the second and third verse+chorus pairs (between Verse2+Chorus3 and Verse3+Chorus4). Between all three verses only the second line is different; as verses accumulate the rhyme scheme of verses is abac, adac, aeac, if labelled cumulatively. In the table the labelling of materials begins anew in each stanza section; melodic lines are present for comparison. If melodic material was labelled cumulatively from beginning to end and across sections, we would be able to recognize the second phrase of the chorus (“do, do, do, do”) and the first phrase of the verse is the same melodic motive.

The overall shape of the song lyrics emerges in recognizing the relationships and combining patterning of stanzas. Patterns of stanzas combine in groupings, establishing ever-larger sections until arriving at the least number of combinations. An overall structure is thereby established at the highest hierarchical level, just as in musical structure. This structure of stanzas is articulated within line lengths, meters and rhymes—in combinations and in divisions.

Table 4.5 Outline of “Here Comes the Sun” stanza sections and sequence of lyrics, with syllables per line, rhyme scheme and relationships of melodic materials.

Free verse texts, and free sections within the lyrics, are certainly found, though these open structures are not as common in songs—Bob Dylan’s “Brownsville Girl” (1986) provides an example of stanzas of varying length (four, five and six lines). Less common still are sections or stanzas of text that overlap different musical settings, though this holds the potential for pre-chorus/chorus coupling. In some songs, if one is able to recognize the text of a pre-chorus and chorus as being a single stanza, perhaps an extended stanza section, their movement through different musical materials could serve as an example of this type of activity. An example of this occurs in the pre-chorus (of eight measures, beginning with “You just gotta ignite the light . . .”) and chorus extended stanza of “Firework” (2010) by Katy Perry.

Poets and lyricists (songwriters, playwrights, film writers, etc.) place concepts, ideas, activities, etc. at specific structural places to shape and control the unfolding narrative. When lyrics are considered for this literary shape and content, an overall structure of the lyrics’ concepts might emerge. The structure of the lyrics might be reshaped when factoring both the sonic and conceptual. “Rhythms of verbal images”—that is rhythms of ideas, concepts, and any literary aspect of the song—might be formed in the strata of the middle dimension, as well as the large dimension. The song structure might remain sectional (verses, choruses, etc.), though articulated within its subject matter or some other aspect of the text (perhaps different characters present in various stanzas, a different topic appearing at differing points in the text, perhaps defined by recurrent and differing imagery or symbolism) will be a structure of the unfolding story in all its dimensions. There is a potential for the structural shape of the lyrics to differ from the sequencing of literary content within that structure. Such a divergence often appears as a progression of some sort, typically driven by the narrative.

Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” (1963) provides a clear example of rhythms of imagery; each line presents a different image rarely connected with those around it. Each stanza is framed by a two-line refrain at the end and with a two-line inquiry from the protagonist’s mother at the beginning; a question-answer antiphony between mother and son is established (Dylan 2016, 59). The internal lines answer the inquiries, and vary in number between stanzas. Most lines are complex and contain several images, and either add surreal detail to its image, present images of characters or of actions within an image of a scene, or multiple images. The number of images per line varies; though most lines contain two connected images, some contain a single image and others three or four. A pattern of speed of changing images is established between the beginning and end of each line, between lines and between stanzas. A number of images of the first stanza reappear in the last (mountains, forests, oceans); most images contrast with others, but pertain to the mother’s queries of “where have you been,” “what did you see,” “what did you hear,” “who did you meet,” and (finally looking to the future) “what’ll you do now.”

Subject matter within stanzas may be another organizing factor. Patterns of topics, of scenes of action, or of repeating refrains between stanzas reinforce the verse and chorus identities. The repetition of text for refrains and for choruses, and the common unfolding storylines of verse narrative solidify the linkage of the musical materials and the poetic topics. The unfolding musings of “Strawberry Fields Forever” verses are grounded by its chorus refrains; though it contains some rhyme, its poetic voice dominates and organizes its montage of imagery and ideas.

Message and Meaning

A difference between “meanings intended by the writer and those inferred by the analyst . . .” (Everett 2009b, 364) can be expected, though there are other points of view as well. Three vantage points of interpretation can seek the meaning of lyrics; each is capable of generating a different meaning. These interpretations are that of the author (lyricist, songwriter), of the analyst and of the listener (the intended audience of the song). Lyrics have surface meanings, and at times deeper meanings (both intended or by chance); searching for deeper meaning can be appropriate at times (or within certain tracks), and not at other times—a significant portion of the countless writings seeking to ‘identify the meanings’ within John Lennon’s or of Bob Dylan’s lyrics attest to how convoluted this can get.6

Unless the author is forthcoming with the ‘meanings’ that were meant to be present, any discussion of author intent is speculative. Songwriters are rarely so revealing. Analysts or lay listeners might be aware of the artist’s history and life situations, and thus inclined to read them into the lyrics; this knowledge does not, however, mean those events are present within the text. Such action seems akin to projecting one’s own interpretation onto the lyrics, into what the artist ‘was feeling or thinking’ at the time the lyrics were written. Even if a lived experience is present in the lyrics, the songwriter may willingly reshape reality. Further, a songwriter might understand an experience only after writing about it, or may not put the full experience into a verbal or sonic form; expression transforms the experience, and also the author; “songwriters . . . are often surprised at what they create and often only retrospectively comprehend what they were attempting to communicate” (Negus and Pickering 2002, 184). Even when the songwriter overtly shares, it can be through implication, with a more abstract poetic voice, or in any other way avoiding explicit communication; the lyrics wilfully open to listener interpretation, to make the lyrics somehow their own story. Of course lyrics can be fictional, and not at all autobiographical; a song might simply be a story.

The interpretation of the audience is highly individualistic; listeners seek meaning in lyrics with great flexibility, in a great many ways. It is important to recognize this is an intricate matter, and exploring this thoroughly is well beyond our scope. To identify a few central issues though, first we must recognize the listener can identify deeply with a song; Allan Moore (2004, ix) has noted “an unintended word can have life-long consequences . . . all these details can become part of listeners’ lives and identity.” Lyrics can invite listener interpretations to complete their narrative; Richard Middleton (1990, 173) proposes that in some songs it is necessary for listeners’ experiences to be used to complete the song’s meaning. Further, lyrics need not be taken at surface meaning, at face value, and such flexibility invites personal interpretation of phrases, scenes, story and moods by individual listeners; what the song means to one is likely not fully consistent to another. Lyrics (in tandem with their performance) speak to them personally, and what it says to them is based on their own experiences and perceptions. The recognition of what is personal, and what is cultural and shared with others is important to identifying an appropriate interpretation.

The vantage point of the analyst will be cultivated as we continue to explore the domain of lyrics. Here there may be some cultural universality, though even between analysts there will be justifiable differences; as we each can only interpret meaning from our own vantage point, “a perspectiveless perspective is impossible” (Moore 2012a, 330). In addressing the general audience listener (although he may as well have been addressing a fellow scholar), Allan Moore (2004, ix) has offered: “And there is no reason why mine [his sense of the meaning of certain lyrics] should be more plausible than anyone else’s.”

As is now evident, for the analyst, the process of determining the message and/or meaning of a text is fraught with potential subjectivity. Navigating this boundary between what is present in the text and what is personal in our hearing/reading of it can be challenging. Some subjectivity is inherent in the analysis process, as we bring our own life experiences, personal perspectives and sense of the world— and even misperceptions and misunderstandings—to the analysis. Conversely, some universality can be sought and a certain amount expected, as topics, ideas, concepts will generate common messages and meanings amongst listeners of the same cultures. Within the goals of the analysis is setting the balance of the universal and the personal in interpreting meaning.

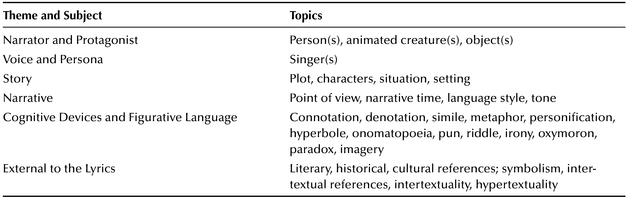

Sub-topics, concepts, ideas, references, images contribute to shaping the lyrics and its overall concepts and meanings. Paul Simon’s Graceland—both the song and the album—are filled with examples. Figurative language devices pull the listener into more intricate relationships with the text, and connections with external sources (texts, images or ideas) push the listener outside the confines of the lyrics and the music to bring the work greater breadth and perhaps more substantive meaning.7

These can all work together, pulling the lyrics to establish meaningful connections, while generating imagery, feelings, and messages well beyond their few words. Lyrics may have “symbol-rich meanings that cannot be expressed in conventional words and thoughts” (Everett 2009b, 370). Indeed, lyrics can be crafted that bring the listener to engage or recognize abstract concepts, aesthetic dimensions and philosophical ideas—all generated from the sparse wording of the song. In some instances, meaning may appear concealed and unclear. Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” is one of many of his lyrics that can leave one wondering which of a myriad of possibilities to accept as its intended meaning; intention cannot be known, though (unless the artist shares it). Some lyrics open themselves to, or even invite, a wider interpretation.

The subject of these concepts, sub-topics and topics, ideas, images (etc.) may reflect or be placed within a specific time period (present, past or future). Popular song is often rooted in the time of its creation, reflecting the then current culture with references, language or topics of the day. The song “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” (1967) is unmistakeably rooted in place and time; Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock” (1970), while also rooted in place and time, speaks to a broader context and with a more universal voice about an event she did not attend (Whitesell 2008, 33–38). A lyric might also present a message and ideas that are more timeless—a more universal context void of topical or cultural references, establishing theme and subject outside the constraints of time. Songs such as Bob Dylan’s “Blowing in the Wind” (1963) and John Lennon’s “Imagine” (1971) “while advocating political causes, employ nonspecific, even mythicized images and a rhetoric of metaphysical questioning rather than activism” (ibid., 47).

Dimensions of the Story

A common approach to theme in song lyrics is the narrative. The following are intended to assist interpreting the narrative song’s story, content, subject and perhaps message, in as much as might be present within an individual text.

Some dimensions of the narrative story (setting, situation and plot) are summarized here:

Table 4.6 Components of message and story.

The plot is the activities, action and events in the story. The plot is often organized toward a particular end; it typically incorporates unfolding drama and time lapse, placing the narrator or other characters in situations. Situation refers to the state of affairs present at a given moment in the story, and can refer to a character’s circumstances at any given moment. The setting frames the context for the song; it is the scene or the backdrop, in front of which the story unfolds—a memorable barroom setting opens Bob Dylan’s “Hurricane” (1976). Setting can establish a point of reference, and include a specific time and place in which the story takes place; it is also the physical environment in which a story or event takes place. Setting may also establish an atmosphere within which the story exists.

Stories typically include characters or imaginary persons (or other personified figures), including the narrator and the protagonist. These are the participants or actors of the drama and story; their presence typically provides central interest and meaning to the text.

The story’s narrator or speaker is integral to all aspects of the lyrics. If appearing as a character within the story, the narrator is a participant. A non-participant narrator is an implied character, or perhaps an omniscient or semi-omniscient voice or presence that conveys the story to the audience, though such a voice is not involved in the activities or story. The narrator gives voice to the lyrics. Through singing, rapping, speech, non-language sounds and more, the voice of the narrator may take many forms.

A narrator might project personality characteristics and traits of an individual through the singer’s performance; this narrator might be provided a history or some other backstory. In other lyrics the narrator may be a non-personal voice—an anonymous, detached, or stand-alone entity. The narrative of many lyrics is a voice within which a listener might project themselves (Durant 1984, 203). The significant majority of song lyrics are presented from the point of view of a narrator. This person’s presence is also known as persona—a concept explored in detail below.

A protagonist is typically (though not necessarily) the main character of story, and often the storyteller. The protagonist is at the center of the story; this character is making the difficult choices and key decisions, experiencing the consequences of those decisions, relaying thoughts and emotions of those situations and decisions. The narrator of a story can be the protagonist only when the story is told from the first person point of view.

The point of view of the lyrics establishes a vantage point from which the story is told. The narrative might be told from a first person, second person, or third person point of view. Each have unique vantage points that shape the listener’s experience of the text/lyrics, and may have a profound effect on the message of the lyrics, and the many dimensions of the recorded song. In this way, one step of the analysis might be to consider the pronouns one encounters. Who are the characters and how are they related? There is a level of distance or intimacy indicated, as an audience or an individual is the intended recipient of the discourse.

A first-person narrative is always a character within the story—as in Joni Mitchell’s “The Last Time I Saw Richard” (1971) or Bob Dylan’s “I Want You” (1966). Narrators refer to themselves using variations of “I” (the first-person singular pronoun) and/or “we” (the first-person plural pronoun). This brings the listener to experience the point of view of the narrator, such as their opinions, thoughts and feelings, etc., but not those of other characters.

In second-person, the narrator addresses “you,” “your,” and “yours”; the narrator assumes the position of speaking to the listener directly (though exceptions do exist)—as in Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” (1965). It can communicate an alienation or distance (this may also take the form of a detached formality) from the events being described, or from the listener/reader. Second-person perspective may be used to guide the reader/listener,8 or to address the audience directly. The second-person form is found with great regularity in song lyrics.

Alan Durant (1984, 203–204) identified four individual distinctions for “you” in rock music. Suggestions through second-person pronouns with unspecified or general direct addressee provide immediacy, and allow it to transcend limitations of formalism:

- Addressed to one specified individual (clear in the context of the song),

- Directly addressing any singular individual,

- An address extending this sense to a general or universal listener,

- Addressed to an addressee that is determined by the listener herself or himself, upon occupying the imaginary position of the singer.

The first-and second-person pronouns in rock songs bring forth a unique possibility of identification. Listeners may superimpose their person on the “I” of the singer; effectively the rock singer is singing out on the audience’s behalf. Alternatively, the listener might occupy the position of second-person addressee, to be the one addressed by the “I” of the singer (ibid.).

In third-person narrative, the narrator refers to all characters as “she,” “he,” “it,” or “they.” The narrator is an uninvolved person or an unspecified entity that conveys the story but is not a character within the story. In an omniscient third person point of view, the narrator knows the feelings and thoughts of all characters, and full knowledge of the situation and setting—as in Bob Dylan’s “Hurricane.” When the narrator only knows the thoughts and feelings of one of the characters—or in some way has limited insight into the situation or thoughts and feelings of some characters—the text is in the semi-omniscient (or limited) voice.

Songs often contain an alternating person point of view—Bob Dylan’s “Tangled Up in Blue” (1975) continually shifts between the first person and third person narration. This shifting is often reflected in a third-person commentary of chorus or bridge sections, contrasting with the unfolding of the story in verses that are written in a first-person voice. In this way, alternating person narratives will shift from one point of view to another; this is often present between the direct communication between narrator and listener that is quite common of verses, and the more detached and universal position of a chorus’ commentary.

More unusual in songs, some lyrics have multiple narrator points of view. Such songs illustrate storylines containing several narratives, and bring a more complex and non-singular point of view of the subject. The mother and son antiphony previously noted in “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” is one example. “All Along the Watchtower” is another example; a different speaker presents each of its three stanzas: a joker, a thief and an omniscient narrator. In Bob Dylan’s “Boots of Spanish Leather” (1964), a man and a woman alternately exchange points of view of one leaving to travel and one staying behind—though it is ambiguous whether the man or woman speaks first, as the one who is leaving (Ricks 2003, 404).

Shifting can also happen in other dimensions of the text. Similar to alternating person, narratives might instead shift narrative time, language style and tone—as in “All Along the Watchtower.” Shifting from one form to another may occur in several of these aspects simultaneously or each might change separately. These changes are most often found between sections—one stanza to another—but shifts might also appear between lines. This provides different sections with the potential of different point of view, narrative time, tone, or language—as is often found between verse and chorus, a middle eight, or a bridge.

Narrative time is the temporal setting of the narrative. This may be simply the point in time of the narrative, or refer to chronological, historical or cultural aspects of the text, or surrounding its events. The time of the narrative fixes the plot in either the past (occurring sometime before the time at which the narrative is expressed to an audience), in the present (events occurring ‘now,’ spanning an arc of real time explained as it seemingly takes place), or in future (events of the plot are set to occur at a later time). Time may progress in real time, speed up (action summarized), be stretched (action slowed down), be paused (story comes to a stand-still while a commentary is presented), or time shift (i.e., the storyline suddenly leaps ahead 20 years, or flashes back a century). The time shifting of Sting’s “Fields of Gold” provides several temporal settings for narrator and protagonist.

Language style of the lyrics communicates information about the narrator and possibly the singer; it also identifies the time period and cultural context of the subject or story. Popular song often represents a conversation and is mostly written using informal language. In using slang, and regional/cultural dialects (often grammatically ‘incorrect’), the text is highly reflective of the social origins of the narrator/ performer or of the subject matter. Language—especially informal language—can bring people and groups of people to unite and connect. It may also divide or distinguish groups, cultures and nations from others. Everyday language is brought into the poetic, and toward the potentially profound, within song lyrics.

This is in contrast to proper language of literature and formal interpersonal situations, which might project greater literacy and social correctness. Formal language minimizes group identity within cultures, and can establish a sense of detachment, as in a conversation between people who have just met. Language shifts can provide stark contrasts within lyrics, instantly transporting the narrative in setting, place and culture, and perhaps through time. Shifting language is evident in the lyrics of “All Along the Watchtower”; Bob Dylan juxtaposes conversational characters and an observational narrator, by using grammatically incorrect, colloquial speech and slang, contrasting with archaic word usage and precise formal language.

Tone presents an overall mood of the lyrics, enmeshed with an overall sound quality; it is an intricate web of feelings that stretch throughout the text. Tone is the lyric’s feeling or attitude as an overarching quality. The narrator’s demeanour, or perhaps the narrator’s attitude toward the subject or the audience will also contribute to the lyrics’ tone or mood—the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” (1968) has a (strangely) unique tone and narrator. In this way, tone also exists as an overall quality of the song, present throughout, and it is a dimension of the track’s form.

Tone is also present in more subtle levels, where it can embody the lyrics’ feelings from one moment to the next. This mood is rarely static. Relating it to structure, a tone might be fleeting and last only momentarily in the words and phrases of the small structural dimension, or it may be reflected throughout middle dimension materials and sections, or shape the character of major sections. Following the unfolding narrative, tone might change as the song progresses—perhaps gradually, often suddenly. David Bowie’s “Changes” (1971) displays these shifts (‘changes’) of tone clearly within the lyrics, the music, and within the singer’s persona.

Persona: The Messenger, Story Teller, Narrator

The individual singer and their personal identity are entwined with the role they assume in delivering the song lyrics.9 Within this role, the individual that is the singer delivers the song by stepping inside a persona, perhaps assuming the lead character inside the song.10 This is clearly exemplified by David Bowie and his Ziggy Stardust persona.11

‘Persona’ originated in early Latin as the term for masks that were used in Greek drama. It referred to the situation of an actor being heard through a mask, which represented a character within a play. Central to this concept, the actor’s personal identity could be recognized by the audience, the public; with their voice projected through the mask’s open mouth they became another—the character within the play (Perlman 1986). The mask provided persona. Here in the song, the singer assumes the role of a character in the song; the mask of Greek drama is transformed into a “vocal costume” (Tagg 2013, 360) that is the persona. “Song characters, then, live through the singer’s voices . . .” (Lacasse 2005, 12). While the performer is an individual outside the text, they establish a persona that exists within the narrative and gives it voice; the persona is the identity of the singing voice (Moore 2012a, 180–181).

The persona might speak from two basic positions in the song; these are vantage points related to the narrative points of view. A persona may either participate in the narrative, or be an observer of the narrative and perhaps the messenger of its subject. In order to better define the persona’s position within the lyrics, Allan Moore (ibid., 181–183) identifies its range of options around three questions:

- Does the persona appear realistic, or overtly fictional? A realistic persona is perceived as emanating directly from the singer; a direct address from the singer. A fictional persona is much the same as an actor assuming a role; the singer unambiguously becomes a fictional character.

- Is the situation described in narrative itself realistic or fictional? The realistic situation is one that might reasonably occur any day, either to the listener or to the larger community of which both the listener and the singer are a part. The fictional situation is beyond the experience of the listener and the singer; perhaps it is an imaginary, mythological world, or an historical context that provides the situation for the narrative.

- Is the singer personally involved in the situation being described, or acting as an observer, external to the situation? The persona is inside and participating in the activities of the narrative, or is outside and observing the situation and plot.

These three positions are not all-inclusive; records are complicated and can defy clear categorization. These categories do provide a valuable reference for situating the persona within the greater narrative, though. They allow a meaningful examination of how the persona is placed and interacts with the narrative to emerge, and begins a definition of the image projected by the persona. Moore (ibid., 183) goes on to identify a ‘bedrock’ normative position (framework) that is very common for songs—a typical set of characteristics that are most common. The ‘bedrock’ position contains the attributes: a realistic persona; persona is in an involved stance; a realistic, everyday situation; the plot takes place at the present time; and explores feelings, thoughts, events of the moment, or a momentary situation. This normative position might establish a point of reference for identifying ‘who is talking’ and from ‘what position,’ as well as their relationship to time, setting, situation and plot. This connects what the persona contains and portrays to basic details of plot and situation.

Stepping outside the context of the individual recorded song for a moment, our sense of persona can be generated from our perception and knowledge of a wider perspective than the individual song. Entire albums (such as Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band) may exhibit qualities of a guiding persona that provides a consistent voice throughout. Further, a sense of persona of an artist or group might emerge from an historical reflection on their catalog—perhaps a number of consecutive releases, perhaps their entire catalog (such as Alice Cooper or Kiss). The sonic signatures of certain producers have generated personas that extend over any number of projects, over any number of artists. These greater contexts may be found useful to scholars, especially in examining stylistic decisions used by some artists/producers (such as Phil Spector or Brian Eno). This has much to do with a sense of tone—tone as an overall sound quality to which the recording contributes significantly.

The persona utilizes tone to project attitude; tone shades the text into an attitudinal position. The singer’s tone of voice communicates an attitude toward what is being said, and toward the subject of the lyrics. This attitude projects into all structural levels, from the topic of the moment through the overall concept of the text. One can ask, is the persona serious, reverent, glib, mad, pained, satiric, humorous, hostile, detached, intimate, loving, playful, ambivalent—or other? Is the tone in this moment, exhibited throughout this section, or an overall mood? The tone of the persona is an interpretation of the tone of the lyrics; these are two different opportunities for establishing mood. The tones within the lyrics and around the performance may be aligned or not; may be complementary or oppositional. Tone is manifest in subtle or pronounced timbre modifications, dynamic and pitch inflections related to linguistics and articulation of melody’s pitch and rhythm, and also in extra-musical vocal sounds. Tone is a product of the delivery, or performance of the lyrics—it is timbre and attitude, sound qualities and demeanor.

Sounds of Language

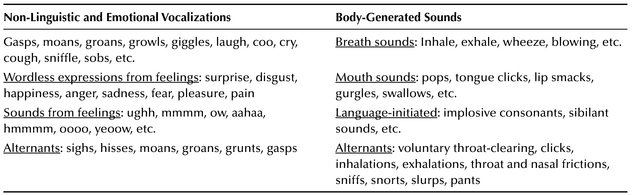

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) might be used as a tool for recording analysis; it can engage an array of language sounds and dialects, and much more. IPA can represent the sounds of language(s) and other utterances, and allow them to be deconstructed and opened for more thorough examination. It can also represent the nuances of the voice in a performance—nuances of language, abstract sounds or paralanguage and non-linguistic sounds.

Word sounds may function as abstract sound, and be separated from meaning. This can occur whether by nonsense syllables or by the sounds within words, and within phrases. The sounds of language, and other non-language vocal sounds, add substance to the record, if not also the lyrics. The sounds of language are quite complex, and the sound qualities of spoken and sung languages are richly varied.

It is a challenge to delineate the subtle sounds of language, given their great variation. Phonetics can provide some guidance to examine language sounds directly. Phonetics engages the sound qualities of the text itself. This represents the sounds and sonic structure of the lyrics, before it is transformed by the song’s setting of the text and the singer’s performance.

Since this book is written in the English language, within the conventions of English as used in the United States (and acknowledging a great many dialects exist), this is the point of reference for discussion.12 Though other languages have different sounds, this section might serve the lyrics of other languages as well.13 Several phonetic alphabets and systems of symbols exist. The International Phonetic Alphabet was devised by the International Phonetic Association to bring the sounds of oral language into some standardized form. It has its origins in the late nineteenth century, and is meant to be adaptable for studying any language; this universal application is an advantage. The North American Phonetic Alphabet (or Americanist phonetic notation) is another system of phonetic notation that is in common use; it was originally developed for Native American and European languages, making the name ‘Americanist’ misleading. The IPA symbols will be used herein because they may reach a wider audience; either system is valuable for studying the sounds of language, as accurately as that might be possible.

The human voice is capable of making many distinct sounds, though only a select few contribute to constructing words in any language—and some different vocalizations will appear in individual languages. Utterances and stringing of select vocal sounds combine to form unique languages worldwide.

Words are the smallest meaningful element of language. They are used in defined grammatical structures, with rules of convention to formulate and communicate their meaning. In this section we are concerned with sound alone (the sound quality of words and language), not with meaning—though meaning does define the separation of words.

There is little universality here, even within the same language. Language sounds are inexorably linked with dialect; language sounds can differ widely while retaining meaning. The same words may have the same meanings but widely varied sound qualities between geographical areas, between different social groups, or ethnic groups—they may even be profoundly different between adjacent neighborhoods. The qualities that bring these distinctions are often clearly present in popular song; they may even be exaggerated. The context and meaning of the lyrics might bring one to extract meaning from dialect as well, though this is not our concern here. Here we are focused on the vast palette of sound qualities within and between the words themselves and how they are shaped by the fuller sound sequence of the sentence.

Words are built in combinations of phonemes, or segments of syllables. Phonemes are abstract units of sound, and the smallest part of a language that can serve to distinguish between the meanings of a pair of minimally different words, a so-called minimal pair. Notice how the words bat [bæt] and pat [phæt] form a minimal pair; the “b” and “p” sounds differentiate the two words (Chomsky and Halle 1968). The sound of the text using the International Phonetic Alphabet appears within the brackets. This represents a standardized representation of the sounds—a type of notation—of oral language. IPA symbols are composed of one or more elements of two basic types: letters and diacritics, which provide description of the letters. Depending on the level of detail one wishes, IPA symbols for the sound of the English letter “p” may be transcribed with a single letter [p] or with a letter plus diacritics [ph] that signifies the “p” is aspirated.

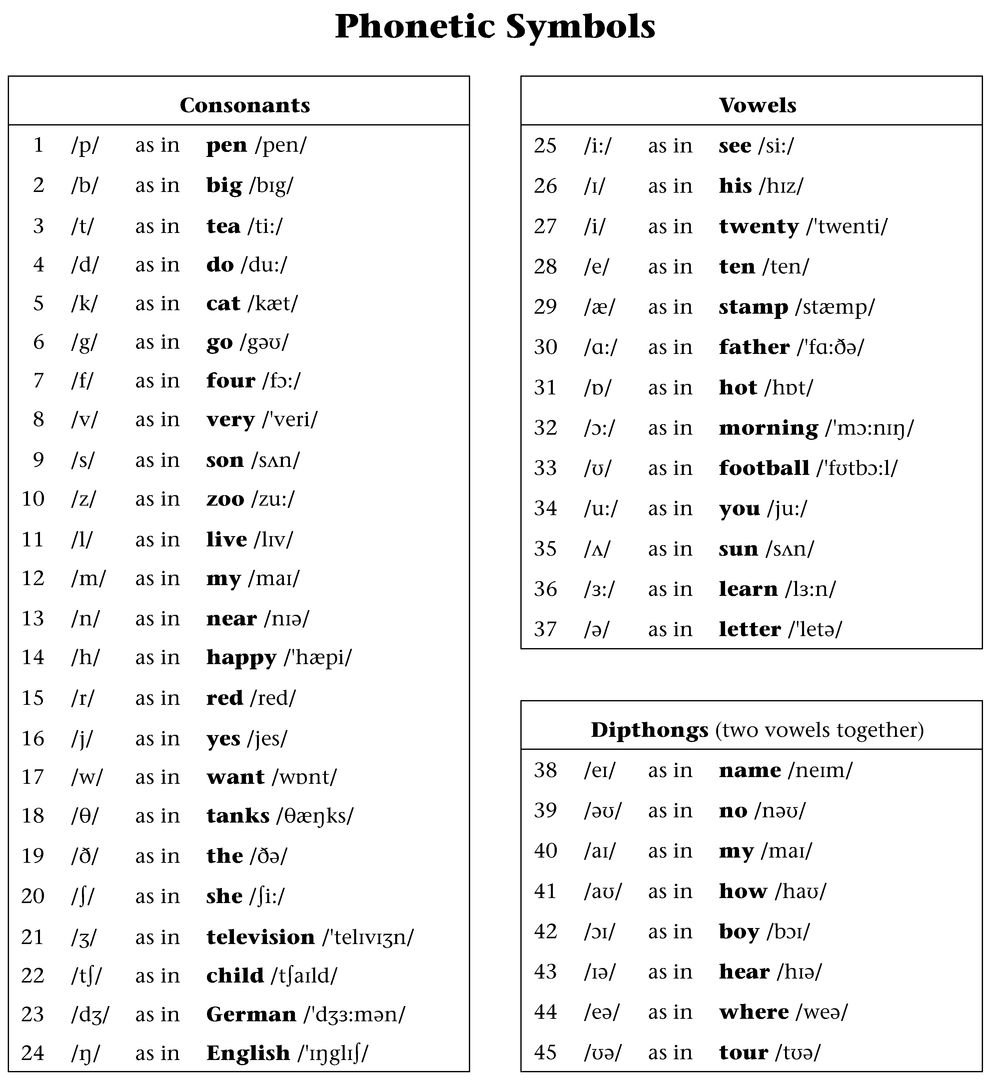

Figure 4.2 Phonetic symbols for English vowel and consonant sounds. Adapted from the IPA Chart, http://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/content/ipa-chart, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License. Copyright © 2015 International Phonetic Association.

The symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet include 107 letters that represent consonant and vowel sounds, the 31 diacritics that are used to modify them, and 19 additional signs that indicate the suprasegmental qualities of length, tone, stress and intonation.14

There are approximately 44 phoneme sounds in the English language. The 26 letters of the alphabet represent these 44 phoneme sounds, individually and in combination; their sound qualities will undergo some variation with accent and articulation. The phoneme sounds are divided into two major categories: consonants and vowels.

Vowel sounds are produced with an open, unrestricted vocal tract; there is no build-up of air pressure above the glottis, and the tongue does not touch the roof of the mouth, teeth or lips. Five or six letters (‘A,’ ‘E,’ ‘I,’ ‘O,’ ‘U,’ and sometimes ‘Y’) are used to represent 20 vowel sounds—‘y’ can be either a vowel (as in ‘sky’ or ‘fly’) or a consonant sound (as found in ‘yellow’ or ‘yesterday’). Consonant sounds (the remaining 20 or 21 letters) are produced by a partial constriction or a complete closure at some point in the vocal tract; these sounds are produced with the lips [p], with the front of the tongue [t], with the back of the tongue [k], in the throat [h], by forcing air through a narrow channel [f, s], or by air flowing through the nose [m, n].

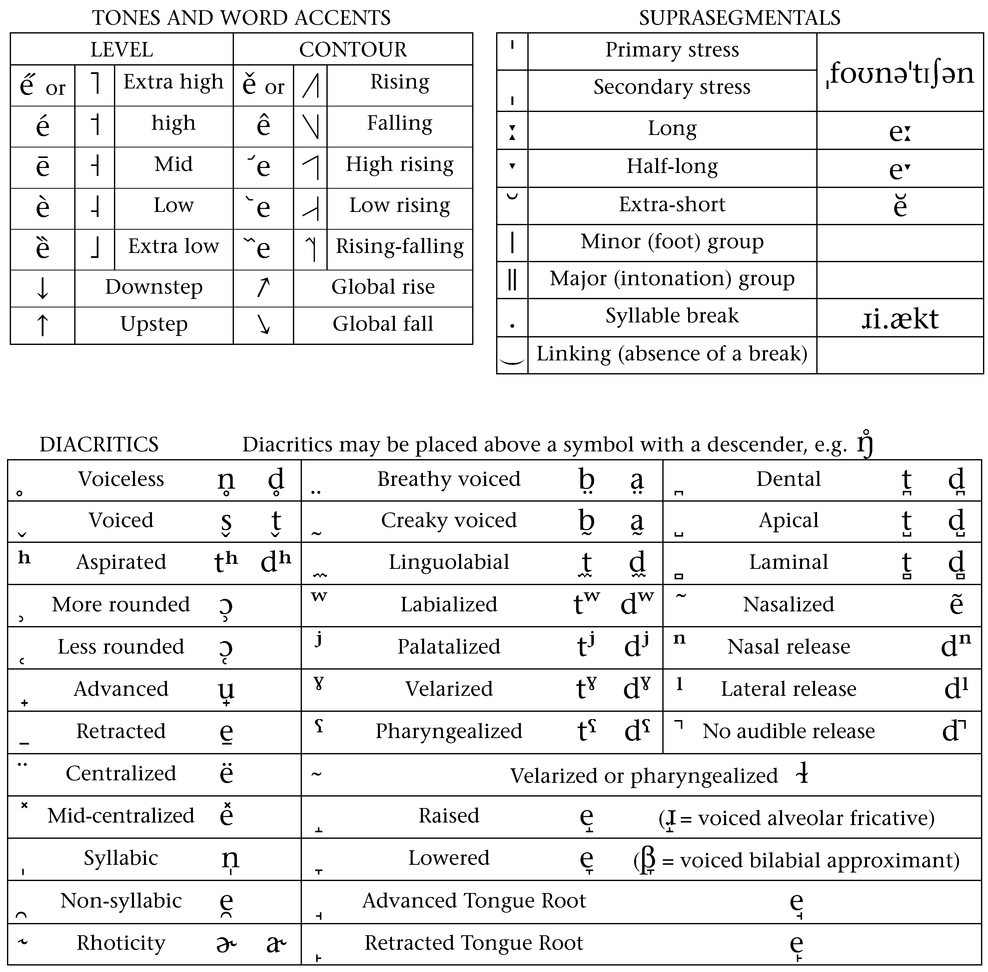

Figure 4.3 Listing of diacritical and suprasegmental IPA symbols. Adapted from the IPA Chart, http://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/content/ipa-chart, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License. Copyright © 2015 International Phonetic Association.

Vowel sounds normally form the nucleus (the center core) of syllables; consonants typically form the onset (beginning) of syllables and will form the coda, or end of the syllable, when one is present. This concept of segments of syllables is especially important when considering sung lyrics. Vowel sounds are the sounds most often sustained by the singing voice; the open vocal tract used to advantage for extending the vowel with minimal stress and effort to the singer’s body. These open vowel sounds are rich with potential for morphing between various forms and tones of the same vowels, and to alter pitch, dynamics, timbres and intensities of the sounds.

Consonant sounds typically articulate the first and last sounds of syllables and words, and punctuate word rhythms. Some consonant sounds can be sustained when singing (such as the “I” sound in “table”), and this aspect of vocal technique is common in records. In song, use of these consonants might imitate vowels, creating new syllables such as when John Lennon sings “fields” as “fi-Idz” in the song title appearing in the chorus’ last line: “Strawberry Fields forever.” In such cases, the sound of the recorded singing voice differs from normal speech and real-life experiences. Constrained consonant sounds do not project well in live (unamplified) settings, but are readily captured by a microphone; Frank Sinatra’s expressive shadings of ‘m’ and ‘n’ sounds are clear examples. While sustained consonant sounds typically cannot be altered as substantially as vowel sounds, they have the potential to change with unique characteristics; consonant usage is significant and worthy of attention in evaluating the sounds of lyrics.

Figure 4.4 Song titles transferred into the international Phonetic Alphabet.

The phonetic symbols for English using IPA symbols for vowels and consonants appear in Figure 4.2. To use the International Phonetic Alphabet, word syllables are divided into phonemes and then transcribed into appropriate IPA symbols. IPA symbols also exist for suprasegmentals, tones and word accents, and diacritics; these are added to the vowel and consonant symbols to further define word sounds. Especially relevant for lyrics analysis are vowel sounds as modified by suprasegmentals and diacritics, as appropriate. Diacritical marks are symbols added to letters; some diacriticals indicate a different pronunciation of a letter is in effect. There are instances when suprasegmental symbols might be incorporated to provide some useful information on the lyrics’ sound qualities. Symbols for tones and word accents are also incorporated in use of the IPA in language analysis. A listing of diacritical and suprasegmental symbols appears in Figure 4.3. A further defining of these symbols and their functions is beyond the scope of this writing but could be valuable to the reader; these are thoroughly covered in sources listed here.15

In using a phonetic alphabet, a significant amount of sonic detail can be extracted and notated. Detailed phonetic analysis can be a valuable supplement, allowing one to recognize sonic traits of the text.16 This may prove especially valuable in identifying or transcribing the sounds of sung lyrics and of paralanguage sounds.

Examining the sound of the lyrics can clarify how sound of the language has been utilized, and how the lyrics are structured related to sound. The sound qualities of the lyrics can be examined without the added layer of meaning. This examination can assist in identifying sonically connected words; word sounds that appear and reappear at structurally significant locations; word sounds with connections imbedded in lines and phrases; and syllables in repeating patterns of many types. Other sonic aspects of the text may likewise emerge, where detailed attention to the lyrics’ timbral qualities is given.

With this section, we have drawn a distinction between the sound of lyrics as written (read silently, originating internally), and the sound of the lyrics as sung (performed, originating externally). This distinction becomes clearer as lyrics and melody fuse into a single expression.

LYRICS IN PERFORMANCE: GIVING VOICE TO THE SONG

Alchemy of Lyrics and Melody

Obvious but significant: song lyrics differ from poetry in that they are written to be sung. This difference takes many forms. The singing voice is substantially different from the narrator of verse; the singer is external to the listener, the poem’s narrator speaks from within the reader. The singing voice represents an individual (and their personal interpretation) interjected between the author of the lyrics and the listener, while the poet (or the persona the poet crafts for speaking) is the narrator of the poem. Poetry is mostly read silently from written form (although many poets write with the spoken word in mind), and may be studied, reviewed, paused, contemplated; the song happens in real time, the singer presenting the lyrics within the performance of the song (Pattison 2009).

In song, the performance itself shapes the text. The drama and story of song lyrics are brought to unfold over time, and lyrics are articulated in time and rhythm. Their sound characteristics are shaped in performance, and perhaps reshaped; perhaps their meaning is enhanced or transformed.

The singer provides voice to the song, through the persona they establish and project, and in their performance. “Aside from their role in signifying ideas, lyrics also play an important role in enabling listeners to construct an image of the persona embodied by the singer” (Moore 2001, 186).

Lyrics and melody blend in fusion. Melody and lyrics form a natural linkage, which is symbiotic. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish where music (melody, plus other elements) and language diverge. Language itself has a musical side—in the hidden melody of pitch inflection and rhythmic pacing and patterns, sentences, words and even syllables have melodic traits. Some perceive certain languages as more melodic than others,17 and some people have speech patterns that are melodic, sometimes even ‘singsong-y.’ All these traits might be amplified within a vocal line, as melodic contours can seem to mirror the intonations of verbal phrases.

Especially common in song verses, melody can have linguistic pacing and inflection that reflects a narrative character; recitative lines are common, allowing the narrative or story to be emphasized over the music; in such cases little might separate speech and the sung lyrics. Here, the text can largely minimize pitch changes in melody, and bring melody’s content to be largely rhythm with dynamic and pitch inflections. A context of “speech rhythm” results, where the sung phrase appears much as it would if it were spoken (Bradby and Torode 2000, 214). At the other extreme, melody itself may take the musictraits of language to great sophistication; instead of mirroring speech, melody can magnify it. Melody can exaggerate the sounds, rhythms and phrasing of text; it may take language traits and rework them into musical effects, or into substantive materials.

While melody and lyrics inherently have great connectivity, in many contexts melody and lyrics will establish traits independent of the other. The two are just as likely to appear with different content and characters—from slightly varied to distinctly different to contrasting. Melody and lyrics may be contrasting or even oppositional in their content and characters, though they are most often complementary in some way, and to some degree. An effective song is likely to have a melodic setting of lyrics that together produce something wholly different than their independent contributions; melody and text working off one another, sharing and enhancing characteristics, bringing the concepts of the text into the activity and character of the melody. Lyrics are elevated by music’s content and context; music is elevated by the sounds and the meaning of the lyrics; together they fashion a more meaningful and more sophisticated voice.

Middleton (1990, 231–232) outlines a three-pole model to this melody and lyrics interaction that identifies how “the hybrid practices of actual popular songs come into being.” The model distinguishes between story, affect and gesture.

In the ‘story,’ words are in narrative form; the voice tends toward speech and can be prose-like; the lyrics direct rhythmic flow and harmonic movement. The text merges with melody in ‘affect,’ where words contain expression and the voice tends toward song, intoned feeling. Words functioning as sound qualities define ‘gesture’; as gestures, words are prone to being absorbed into the music, and the voice may resemble an instrument. While individual songs might not clearly fall into any one of these three practices, one trait is likely to dominate within any section or song. These concepts might help guide an understanding of the relationship(s) of lyrics and melody.

Dai Griffiths has identified the concept of ‘verbal space’ as an alternative approach to evaluating phrase structure of lyrics within the track. Verbal space is the result of “the pop song’s basic compromise: the words agree to work within the spaces of tonal music’s phrases, and the potential expressive intensity of music’s melody is held back for the sake of the clarity of verbal communication” (2003, 43). The idea is the music’s phrasing creates spaces, and the performed words occupy a portion of that phrase. The approach seeks to establish a ‘word consciousness’ to systematically explore how the words and lines of the lyrics work. Verbal space is explored more deeply in Chapter 5’s observations of lyrics.

Phrasing and the words produce lines, just as with poems. The prevailing time unit and hypermeter establish the clear dominant phrase length within which lines of text are contained. This phrase length is the basis for this examination. Griffiths conceptualizes pillars at each end of the phrase, with the lines of words unfolding in time, from left to right. Between these pillars there is a point where the words begin and where they end; this establishes the boundaries of the line of text.

Within these lines, phrases can be evaluated for their word content. Lines can be full or empty, and words can be positioned at various points on the line. How the words occupy the space is the central issue; compiling information on syllable count and placement of words allow the relative density within and between each line to be revealed. This ‘syllabic density’ (or syllable count) reveals important information of the word-presence in the line. This density is impacted by word rhythms and tempo, by the speed of a song and the way it is phrased. The approach offers a way to understand the relationship between lyrics and the relative speed of their delivery.

Changes in density as the song progresses can be telling; Griffiths (ibid., 47) notes a doubling syllable count in a middle-eight is common in some pop song styles. Patterns of density might emerge, along with other aspects of syllable density and rhythms. Verbal phrasing and musical phrasing will come together in many aspects of rhythm, as music and words trade off each other’s rhythm. Other characteristics will be readily apparent in the data collected here, such as a change in syllable count shaping a stanza, or propelling motion within a line.

This concept of verbal space has considerable potential for the collection and evaluation of other lyrics-related relationships, as well. Repeating words or word sounds might be identified in lines; literary information of story, subject matter. Drama and pacing of action can be collected and made evident as well; Griffiths notes “the return of the pillar can be a moment of some drama” (ibid., 43). This concept of verbal space might be broadened to determine what information is to be collected (beyond syllable count and placement); we can develop ways of evaluating and talking about the proportional relationships within the verbal space of any particular song that begin with syllable density and perhaps encompass word sounds and rhythms, meaning and story, and more.

Just as a prevailing time unit might flex, verbal space can be malleable. Verbal space can change position, both within the time unit and shifting to overlapping musical phrasing. It can extend or contract in time as the line is shaped. This can be a valuable concept, as one can readily observe how activities shift with and without the presence of the vocal, as well as observe central characteristics of the performance of the lyrics—and ‘anti-lyrics.’

Within the anti-lyric, the “emphasis shifts away from sonorous rhythm towards the detail of its statement, away from rectitude of rhyme and rhythm towards the novelty or interest of words and ideas” (ibid., 55). More prose-like lyrics loosen language and sound; here Griffiths describes Patti Smith in writing: “[T]he words are free to lose the markers of lyric, rhyme and syllabic consistency, in favor of a looser relation more akin to prose forms: less poem as analogy, then, and more short story, novel, letter, confession, manifesto” (ibid., 54).

Sound Qualities of Sung Lyrics

The singing voice and its musical line introduce characteristics and dimensions, and add many sound qualities to the lyrics.

To start, all human voices are unique; each contains a vocal timbre and speaks (sings) with a vocal style like no others. The unique sound of each voice is a one-of-a-kind musical instrument. A singer’s unique sound adds qualities to the song lyrics that are unmatched by any others. Each voice contributes in its own way to support the presentation of the text, and add to the character of the persona. In production, this brings great significance to matching the song (with its lyrics, music, persona) with the sound and character of the individual singer’s voice—and to the singer’s performance style and persona.

In the recorded performance the persona becomes more fully developed. It manifests as a synergy of the content and expression of musical material, the literary and dramatic content of song lyrics, and the expressive qualities of paralanguage, non-linguistic vocalizations and the real-life qualities generated by physical sounds from the singer (such as breath and mouth sounds).

We recognize the music domain of the sung line is most closely linked with melody, while other musical qualities (rhythm, dynamics, register, timbre) can be significant. The lyrics domain continues to carry the sonic substance of linguistics—the rhythms, timbres, inflections, accentuations and diction of speech—and layers of communication and literary meaning. This traditional connection plays out in the shaping of individual words and word sounds, the individual lines of text that are fused with lines of music, and the lyrics and the vocal line as a whole. The persona is deeply enmeshed with its delivery of the lyrics and its performance of the melody.

Returning to the singer, we recognize the sound qualities of sung lyrics are a blend of the timbre of the individual’s singing voice and the qualities of the language. This blend establishes the singer’s voice as a unique musical instrument, and the singer as a unique individual, capable of projecting a unique persona. Additionally, the individual singer has an inherent vocal technique; technique is often influenced by speech dialect, and will exhibit personalized characteristics of performance style and sound quality.