Chapter 9

Loudness, the Confluence of Domains and Deep Listening

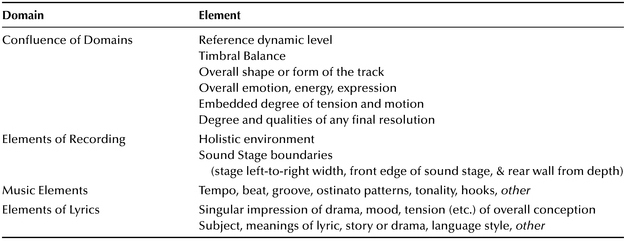

This chapter explores three subject areas: the recording element of loudness, the confluence of all the track's contents and resulting timbre percepts, and a more thorough coverage of deep listening (a subject briefly introduced in Chapter 2). These are presented by dividing the chapter into four parts. Together these topics (1) conclude our exploration of recording elements, (2) situate recording elements within the confluence of all domains, (3) acknowledge timbre as a confluence, and (4) introduce the reader to new ways of listening to tracks.

In the first section, loudness as a recording element is the last of the recording elements to be explored. It is discussed last because loudness determines if and when all other elements are audible. It is also, perhaps, the most misunderstood of the elements. Loudness is examined in its appearances at all levels of perspective, ranging from the individual loudness contours of partials inside the spectral envelope up to the overall loudness contour of the track (program dynamic contour). Loudness balance, loudness levels and contours of sources, and source performance intensity (a timbral quality) are each in turn presented in detail; each are central concerns of records. These percepts commonly bring challenges to the listener’s sense of prominence, and largely shape expression leading to listener interpretations.

The second section presents the ‘confluence’ that leads to the perception that all elements blend; all elements of the three domains, all contributions of performances within the track, along with the outside semiotic associations, affective states, and so forth entwine within listener interpretation. The mix stage of the recording process is used to illustrate confluence concepts. Discussion begins with the confluence of recording elements, shedding light on how they may combine to establish larger concepts of how recording shapes the song; this is often associated with the three percepts of lateral image and sound stage width, distance and depth, and timbral balance. Prominence is further explored in this context. The exploration of confluence leads to the third part, ‘timbre as confluence,’ and a presentation of timbre as a multi-domain and multi-faceted percept. Timbres of sound sources and the timbre of the track are investigated as a confluence of domains; this allows the analyst to engage the contexts, character and content of sound source timbres and the timbre of the track, and leads to engaging crystallized form. A detailed account of crystallized form concludes this section.

The last section of this chapter expands coverage of deep listening. Deep listening concepts have been introduced throughout this book, though not explicitly. It is the basis for numerous approaches offered for hearing many of the qualities of the track, especially recording elements. This chapter concludes by contrasting open listening and directed listening. The deep listening principle to allow whatever comes along to hold equal potential is a significant aspect of our framework.

LOUDNESS AS A RECORDING ELEMENT

Loudness is the perceived magnitude of sound; it is the sensation of the amplitude of the waveform. Loudness is the percept resulting from the psychological impression of the physical intensity of pressure (sound pressure) (Handel 1993, 63). Loudness as a recording element utilizes our sense of this sensation of amplitude.

Loudness, though, can encompass more than sensation. Loudness “is a concept that has implicit meaning for nearly everyone” (Schlauch 2004, 317) yet its sense of magnitude is subjective to the individual and to context (both cultural and environmental). All of us might ‘know’ when a sound is soft and when it is loud, but we all carry our own sense of these concepts, and this sense of ‘loud and soft’ shifts. These ratings of loud and soft are largely meaningless out of context—they carry no association to any actual and measureable sound pressure level. Environment context impacts ‘loud and soft’ so what is perceived as loud in a small room might be moderately soft from the back of a lecture hall. Cultural and social context are even more complicated, adding norms, notions of acceptable levels, and more; a softly spoken word in the midst of a noisy crowd is far different than the same level of speech within a quiet theatre. Loudness percepts are subjective between individuals, are subject to social and cultural conventions, and are perceived differently within various contexts. In addition, perceived level of loudness can vary under influence of other elements—whether or not the actual amplitude of the signal differs.

Perceived loudness can be significantly transformed without an actual change in sound level. We learned, beginning with earliest psychoacoustic studies, that functional dependencies exist between loudness and all other elements, and that there are underlying psychological and physiological factors that may impact loudness perception. Spectral content, duration, time relationships, bandwidth, frequency/pitch level/range, and even visual cues (experienced or imaged) are among percepts that can transform the experience of perceived loudness. Even surprise, shifting attention, pleasure, interest, and discomfort impact loudness perception—psychological influences on perceived loudness can be highly influential, and highly personal. Loudness is a subjective impression we can “assume to be influenced by different nonsensory factors and biases” (ibid.,318), and by selective attention and focus on perspective level, as much as the impression of loudness is influenced by other elements within the sound and by the sound qualities and aesthetic activities of other sound sources. Loudness perception has many layers of subjective influences, laid upon the subjective impression of the sensation of the magnitude of sound.

Loudness manipulation is an important function of recording. Loudness levels of sources and sounds can be profoundly shaped by the recording process. When many of us consider the recording process, our thoughts turn to changing loudness levels of sources and mixing them together in different proportions from what occurs live (or what might have occurred live, given appropriate circumstances). The subtle qualities of loudness, then, can provide qualities and relationships that distinguish tracks as well as the sources they contain. Loudness can create surreal relationships of sounds, where gentle whispers can be incorporated at very loud levels, and instruments performed with great exertion are altered so the timbre generated by such a performance appears at a subdued loudness level in the mix; the balanced mixture of sound sources that comprise the track’s aggregate texture need not reflect acoustic realism.

Loudness as a recording element is focused on the sensation of amplitude, separated (in as much as it is possible) from context of the performance (performance intensity, timbre, etc.). This sensation is loudness as loudness alone; it distinguishes loudness as a recording element from dynamics as a music element, and the dynamics coupled with loudness of performance. Here, the loudness percept and observation is separated from all of the influences of interpretation and impression; it is the perception of actual physical sensation. Loudness can be perceived as sensation, but typically we process loudness quite differently. In our daily experiences, loudness is rarely experienced solely as the sensation of the magnitude of the sound. It is counter to our natural listening tendencies to process (hear) loudness as sensation alone (without influences outside the sensation of magnitude). To separate listening to loudness from the above mentioned factors requires intention, and a control of attention and focus; this listening process seeks to isolate sensation from other influences within the sound. In this way, listening for loudness alone pulls the sound or sound materials out of context and the subjective factors they contribute to the interpretation of the sound’s loudness. This attention to loudness is a critical listening process; it examines the experience as a sound object, void of causal factors and contextual implications. Attention to dynamics, as stated above, incorporates context and character of sounds and materials; dynamics is as much (and often more) about timbre, expression, energy, intensity, and nonsensory factors as it is about the sensation of loudness.

This separation makes it possible to approximate actual loudness levels against a reference, and to calculate loudness contours over time. The sensation of loudness is observed within the context of the track, a context established by its reference dynamic level. Loudness as an element of recording shares an equal role in shaping the track. Hearing the percept of loudness as a sensation of the magnitude of sound can unveil sonic characteristics and gestures inherent to the track that might otherwise go unobserved. The recording element of loudness/dynamics can add dimension to a recording analysis at all levels of perspective. Loudness establishes the presence of sounds and sound sources, but does not in itself establish prominence.

Prominence and Loudness

Attention itself can play a role in loudness perception. Attention is the act of bringing active awareness to the listening process. It can also be holding something within the center of that awareness—an act that by its nature diminishes the prominence of all other sounds, impressions, thoughts, aesthetic ideas, materials, etc. What is held in the center of one’s attention is most prominent to the listener; this prominence from focus of attention is often mistaken to also be the loudest aspect of the track.

Prominence is what is most noticeable or conspicuous at a particular moment in time; it is what has grabbed the listener’s attention. It is not necessarily the most important or most significant sound or material in the track, but only what the listener—at that moment, or in this listening—finds most interesting (Moylan 2015, 452). What is most prominent is also not necessarily what is loudest; prominent sounds are often not the loudest. A sound can be most prominent in the listener’s consciousness, while being at a lower loudness level than all other sounds.

A sound, sound source, aesthetic idea, lyric or musical idea can dominate the listener’s attention for a myriad of reasons. All elements of the track have an equal potential to provide qualities that cause sounds or materials to standout and be noticed. The entry of the lead vocal very often captures the listener’s attention, and at least for a moment can seem to dominate by loudness; when language is present, or pronounced affects of a voice, our life experiences direct us to give it our attention. Prominence can be personal, and influenced by the listener’s prior experience; what stands out to listeners on a personal level can be highly unique.

Unexpected events can attract attention and thus bring prominence, as can those that are unusual in some way. There is a prominent hi-hat entrance in Phil Spector’s mix of “Let It Be” (Let It Be, 1970) at 0:53. The instrument is not the loudest in the mix. It is prominent because it is the first appearance of a percussion sound in the track, and it is a new addition to the texture. The listener’s attention is likely immediately captured by the new sound that is unlike anything that has preceded it—though they may also remain engaged in the lead vocal melody or the content of the lyrics. Immediately the instrument’s unusual spatial identity becomes pronounced as its delayed iterations provide movement on the sound stage. Never is it the loudest sound, or the track’s most significant aesthetic voice. Whether or not it is more prominent than the lead vocal rests in the attention of the listener. Shifting one’s focus of attention between the lead vocal, piano and hi-hat, one might experience a shift in loudness accompanying a shift in prominence, or awareness. Recognizing this shift in prominence can lead toward experiencing the sensation of loudness decoupled from other aspects of sound.

Prominence can be influenced by interpretive factors, and our perception of it may be detached from the actual context of the track. Prominence can be brought into context, though. This is accomplished through intention to perceive all sounds and activities in the track as being equivalent to all others. A balance of prominence (an equality of all that is occurring) will allow one to ‘hear’ all sounds as equivalent. This can be accomplished by directing attention to a higher level of perspective, where the sources (or whatever is being compared) can be heard as equals; this can reveal their differences and unique states most accurately. In this way we can perceive the balance of loudness levels without the influence of prominence. This chapter’s praxis studies can assist the reader in acquiring skill in these areas.

Measuring Loudness Perception

Measuring loudness and establishing identifiable (or perceptible) loudness increments is highly problematic, and not entirely possible.

First is the matter of equal loudness throughout the hearing range of pitch/frequency. As we have learned, two sounds of different frequencies will very likely require different physical amplitudes to establish the sensation of equal loudness. The sensation of loudness can change throughout the hearing range, while levels of acoustic energy might remain consistent—and these inconsistencies of loudness sensitivity are non-linear, and vary significantly at different pressure and frequency levels (as the equal-loudness contour previously informed us). Loudness perception of the track is linked with the loudness level of playback, and its ability to reproduce the frequency range with relatively even response. Identifying equal loudness levels between diverse pitches and frequencies (and the timbres presenting them) is one significant problem of measuring loudness.

Identifying increments of loudness levels is the second significant problem we encounter.

Loudness (a subjective measure) is often confused with sound pressure (Mather 2016, 128–131). Sound pressure is a physical characteristic of how tightly air molecules are compressed together; as the displacement and compacting of air molecules increases (as a sound body moves farther) the greater the pressure increase in the waveform. Sound pressure is measured in decibels as sound pressure level. When we measure the physical amplitude of a sound, we identify its sound pressure level and establish its relationship to a reference level; we arbitrarily choose one value of sound pressure as a reference, and then measure all sounds as relative multiples of that reference level. Thus, the decibel is a comparative measure (a ratio) relating a reference value of the threshold for human hearing1 to the current sound’s measured sound pressure level. This measure of amplitude does not transfer into perception for numerous reasons. The most obvious might be the range of loudness we can perceive. If we accept the threshold of pain (for most listeners) to be 160 dB SPL, the loudest sounds are about 100,000,000 times more intense than the slightest perceivable sound (threshold of hearing for young ears); workable numbers are derived by converting the ratios to the logarithms of the ratios as decibels (dB). The sensations of loudness and sound energy are not proportional, but are calculated as a logarithmic function. Decibel’s logarithmic scaling is not helpful for establishing perceptual increments, as an increase of 3 dB is a doubling of power, but this is unrelated to an increase in perceived loudness; a sound 10 times the intensity as another is 1 Bel greater in loudness. (B. Moore 2013, 133–167) We “can only infer loudness from objective measures” (Schlauch 2004, 318); the measure of sound intensity does not transfer into a measurable perception of loudness.

The methods of measuring loudness explored in psychoacoustics, music psychology and recent ecological studies have little to offer recording analysis. The methodologies used to study loudness sensation have ranged widely. They have included paired comparisons, loudness matching, magnitude scaling, category ranking, cross-modal matching and psychological scaling; included also are studies in ecological loudness—the relation between loudness and the naturally occurring events that they represent. Much about loudness has been examined—both as simple stimuli in laboratories and as environmental sounds.2 While these studies have further informed our understanding of loudness perception, they have not opened a path toward devising a way to identify and compare loudness levels against some scaling or objective measure (like we do pitch and frequency). Our means to engage loudness levels—identifying levels and differences (intervals) between levels—has not advanced in a way that can be incorporated into studying the content of tracks. Loudness levels cannot be doubled to establish an identifiable clone of itself at another level of sound pressure, as pitch can be recognized as being an octave higher; the range of loudness cannot be divided into equal increments that are perceivable and recognizable, such as the half-steps of pitch.

Loudness in the Context of the Track

The category ratings of dynamic markings remain the most readily useable scale available to compare loudness levels and loudness relationships; dynamic markings are range areas of dynamics/loudness, not discrete levels. Discussed at length in Chapter 3 and the following: dynamics differ from loudness in that they reflect timbral characteristics, energy, expression, intensity; dynamics carry subjectivity of interpretation and intermodal connections (physical exertion, connotations of expression, etc.); dynamics are relative to the context of the track. Further, a range of loudness levels exist within each dynamic area—and the actual loudness levels of areas can overlap (also a reflection of dynamics privileging timbre over loudness).

Loudness as a sensation of sound intensity may be situated within this context, with recognition of its sensation being associated with, though distinguishable from those of dynamics. As a recording element, the sensation of loudness is understood within the context of the track. Its level may be defined within the continuum of dynamic ranges.

The reference dynamic level is used to relate dynamic levels, and has been adapted and adopted here (from what was presented earlier) to calculate loudness. It is a holistic impression of all of the sounds of the track and their musical materials and performances; this impression also embraces the content of the lyrics and the meanings and affects it generates. Reference dynamic level was discussed at length in Chapter 3, and will be discussed in more detail here.

The RDL is a specific level within a specific dynamic area; it can be placed at a precise point on the continuum of dynamic ranges, representing a clearly defined level of intensity. The RDL is a stable, unchanging reference within a track; no matter what occurs within the track, the RDL remains a consistent reference.

The track’s reference dynamic level (RDL) provides a stable level of intensity against which levels of sources and sounds can be calculated. Loudness will be identified on the basis of sensation alone, and placed within the context of the track against the ‘conceived’ loudness level that is implied by the reference dynamic level; this carries modest subjectivity from (1) the analyst’s determination of the RDL and also of (2) the transference of the RDL’s ‘dynamic’ level into a loudness level sensation. The RDL implies a ‘loudness level’ that reflects the energy, intensity and expression of its ‘dynamic level’ related to music contexts (pppp, mp, etc.). To allow this transfer, the thresholds of hearing and pain need to have corresponding dynamic levels. The reference levels of the threshold of hearing and the threshold of pain have been assigned the dynamic markings:

The selection of these markings is somewhat arbitrary; five p’s and/or five f’s might seem appropriate to some analysts. Some analysts may find tracks that require more than five increments to reflect its dynamic continuum. These were chosen because they are rarely encountered extremes in musical score markings, and the markings represent rarely encountered extremes of loud and soft within musical contexts. These markings will typically allow for a clear observation and presentation of data. The analyst may adjust this scale if it seems appropriate to the track; for instance, some metal tracks may use only a range from f–ffff, while a folk track might use a range of p–mf .

Using the RDL and these references for extreme levels, loudness levels encountered might be understood and calculated within the context of the individual track. Calculating and comparing loudness levels utilizes numerous processes. They can differ somewhat at various levels of perspective and with various types of observation. Nearly all can be related to one or several of the following steps, however:

- Identifying the level of the sensation as compared with that of the RDL; this determines its loudness level within the context of the track

- Matching or comparing loudness levels within the same gesture or percept stream (a musical line, for instance) at different points in time; this establishes points within a gesture, and allows loudness contour to be mapped against time

- Matching the loudness sensations of two or more different sounds/sources occurring simultaneously; this allows separate parts to be observed for their relationships and interactions, as well as their individual characteristics

- Placing loudness within dynamic ranges from an interpretive calculation of sustainable physical exertion (see Chapter 3)

Interpreting Reference Dynamic Level and Crystallized Form

Crystallized form is the highest dimension of form; it is the track (in its entirety) existing out of time, ‘heard’ non-temporally within the experiential present. Perceived in an instant of realization, it is a single, multidimensional shape, and a large-scale nonverbal conception and experience. Crystallized form is an aural image and a large-dimension sound object—a unified presence of all qualities present at once. It establishes a sense of knowing the track’s fundamental substance (manifesting as a core essence, inherent nature, a unique presence) and its individual form (multidimensional shape) and character (energy, expression, affects, meanings).

In the silence after the track, allow the listening experience of the track to dissipate into a single awareness and reflect on the impression that remains. Reflect on this presence of the track that lingers in your memory and psyche, in your consciousness and awareness. The goal is to not ‘make sense of it’ but rather to ‘recognize it’ for what it is, perhaps to ‘feel’ its character. This overall presence is—at least in part—crystallized form.

Within this impression and conception is a sense of the amount of energy and the level of exertion of the performance, the tempo and the speed of motion, and the magnitude of intensity within its expression; these are supplemented with the drama and meanings of the lyrics and the spatial attributes and other characteristics of the recording. These all coalesce into a manifestation of the performance intensity of the track.

This performance intensity of the track is the reference dynamic level (RDL). The goal, here, is to experience the RDL as a sense of the intensity of the track. Perceived holistically and considered without interference from verbalization, it is a single level of intensity that embodies the track.

The reference dynamic level is the part or quality of crystallized form that embodies the intensity of the track—in all the elements and materials and outside associations that shape and establish it. While Table 9.1 presents factors that potentially influence RDL, it is important to remember this it is the result of an experience, not a calculation. Listening from the position of accessing musical expression and an appreciation of the singular, coherent whole will open attention and awareness; attention is directed toward nonverbal qualitative reflection and a recognition of its expression; one that is based on musical thought and aural imagery. This contrasts markedly with the analytic reasoning required of analysis, which engages the rational thought processes of calculating, deducing, problem solving and otherwise attempting to assemble a result for the RDL—a process that quickly and prematurely brings verbalization, and does not access the inherent character of crystallized form and the intensity of the RDL. This will be addressed in more detail later under crystallized form.

Revealing an RDL involves listening and finding the level at which the track’s energy and expression reflect its intrinsic character. Table 9.1 is presented to identify sources that may contribute to the RDL of a track. They are not intended to bring the reader to divert attention to these sources; attention should remain at the highest level of perspective, to experience the intensity dimension of the track. Each track, every individual track, will have a different combination of factors, and different proportions of factors that formulate a sensation of RDL that is unique. There is no formula for RDL, as it is an interpretation. One can expect one’s sense of the RDL to evolve—especially while one is becoming more acquainted with a track. As an interpretation, the RDL will (to some unknown extent) reflect the analyst’s biases, though this interpretation should (as much as is possible) reflect an objective interpretation of culturally shared perceptions.

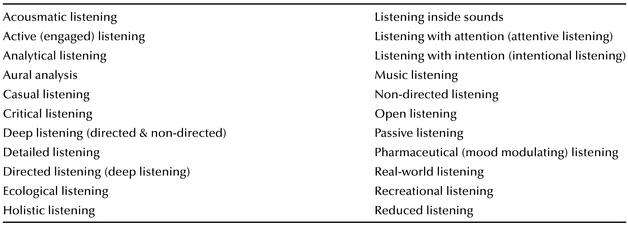

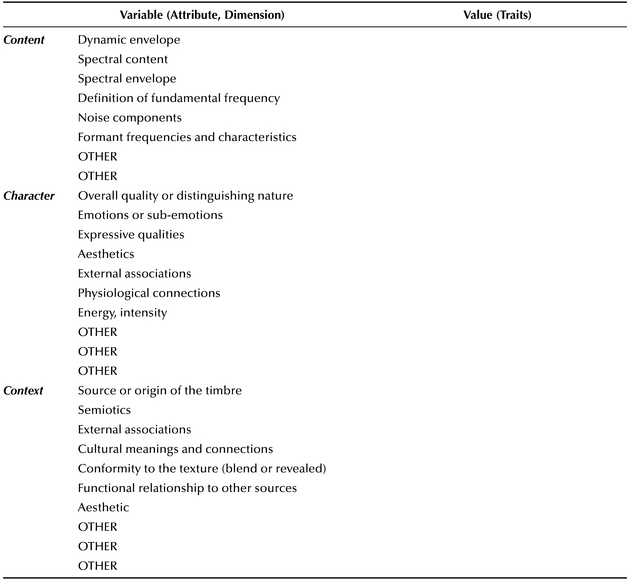

Table 9.1 Potential factors that can influence reference dynamic level. These factors potentially provide a variable level of influence toward establishing a singular, overall impression of intensity for the individual track.

Overall Loudness Level of the Track

A hierarchy of loudness-level strata exists similar to hierarchies of other elements. The above comparison types for loudness levels will occur at all levels of perspective, except one sensation of loudness exists at the highest level of perspective and comparisons will be made only within that single contour. Table 9.2 illustrates the hierarchy of loudness levels.

Attention to the sensation of loudness can be directed to any of these levels of perspective. Simultaneous sounds or successive sounds can be compared in all of these perspectives—allowing a single stream of sounds to be followed, or various streams to be compared to one another. These levels of perspective differ greatly, ranging from the singular loudness of the aggregate texture to the strata within a sound’s components and its reverberation (loudness levels within timbres were encountered in Chapter 7, and Chapter 8 introduced loudness levels within environments).

At the highest level of perspective, the track is distilled to a single sensation of loudness; we perceive this level to change continually and to form a contour across the entire track. In earlier writings (Moylan 1992 and 2015) I have referred to this as ‘program dynamic contour.’ In these I was writing from the vantage point of an engineer/producer (I prefer the term ‘recordist’)3 where the term ‘program’ has been commonly used to describe the overall track or its singular sound; ‘dynamic’ was used synonymously with the sensation of ‘loudness’ to connect the two concepts (though this connection was rarely explicitly articulated) in order to connect the role of loudness sensation to the musicality of the track. This overall loudness level could be re-named as ‘track loudness contour’4 should one wish to be more accurate and perhaps less confusing. I will use both terms synonymously as this discussion unfolds.

Table 9.2 Hierarchy of loudness-level strata as a recording element in relationship to levels of perspective.

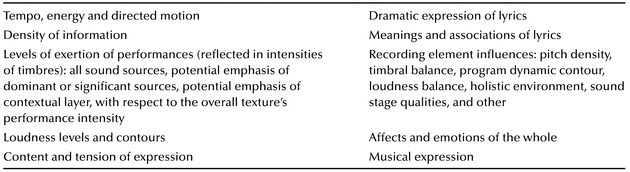

The track loudness contour is the single loudness-level of the track’s aggregate sound; it is the result of the combination of all source loudness levels. It helps some to envision this sensation and concept by thinking of a single VU (voltage unit) meter that displays a representation of the signal level, following the loudness level of the program as it potentially changes at every moment. The contour is the shape of the track’s changing loudness that is revealed as it progresses from beginning to end. This loudness shape often has structural significance to tracks, and can support its drama; this sensation in itself it is capable of generating movement and tension within the track. It is unusual to listen for overall loudness of many sources in our everyday lives; many practicing musicians, including conductors, are not aware of or seek to engage this sensation of combined loudness levels, though some certainly do. Recordists, in contrast, often bring their attention to this level of detail while shaping various stages of the recording process. This overall loudness contour may be deliberately shaped in the recording process; its subtle changes are often the result of the track’s arrangement or of its mix; these are significant contributions to the character of the track.5

This loudness shape often has structural significance to tracks, and it can support its expression. Jada Watson and Lori Burns (2010) use the loudness-wave shapes of a track’s two channels to illustrate this overall loudness as amplitude; while this is not precisely aligned with program dynamic contour (it depicts a physical measure and not the perceived dynamic shape, and it treats channels independently instead of bringing attention to a single impression), such a diagram can guide perception and observation, especially when acquiring this skill. They note their amplitude diagram of the Dixie Chicks song “Not Ready to Make Nice” (2006) “reveals that the song has an overarching increase and decrease in dynamic amplitude (< >), a design that reflects the growing intensity of the vocal gestures and instrumentation and complements the intensification of anger and resistance in the lyrics” (Watson & Burns 2010, 345). Here they connect structure, performance intensity, dramatic expression and the content of the lyrics into a statement that provides much important information to the track, and to its overall loudness shape.

A program dynamic contour graph allows the loudness contour of the track to be observed and notated. Listening to this overall loudness sensation will be a new experience to some readers, though it can be developed with directed attention; praxis study 9.2 can guide this experience. Engaging this level of perspective will lead to new observations, even for tracks one already knows well. When engaging the track’s loudness contour care should be taken to remain focused on the sensation of loudness alone, and to remain uninfluenced by the timbres and intensity levels of the ensemble or the drama of the music. Timbre and expression characteristics (and other percepts) can bring the impression of increased or diminished loudness, without an actual change in acoustic energy; likewise, loudness can change without a change in timbre (or another element of recording or another domain). Remember to monitor playback level; consistent playback level is needed for accurate observations between listening sessions.

Figure 9.1 VU (volume unit) meter. Image courtesy of API (Automated Processes, Inc.).

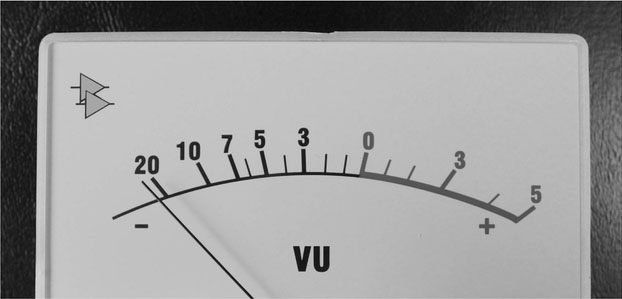

Figure 9.2 Program dynamic contour (track loudness contour) graph of the Beatles' "Here Comes the Sun," Abbey Road (1969, 1987).

Figure 9.2 illustrates the changes in overall loudness level throughout the track “Here Comes the Sun” (1969, 1987). The graph contains the reference dynamic level of the track, against which the contour can be heard. Imbedded in the contour are shapes of loudness that correspond to structural divisions; as the shapes emerge within one’s hearing of the track, their role in defining sections through their repetition becomes apparent. The loudness shape of the track is clearly evident from its beginning at the lower portion of mp to its peak within ff. The wide dynamic range of the track contains subtle changes of loudness as well as large and sudden shifts.

“Here Comes the Sun” is among the uncommon tracks in which the reference dynamic level is prominently experienced. During the final moments of the coda, the level of the track loudness contour matches the track’s RDL; the reference dynamic level is audible as the track’s overall loudness arrives at the track’s overall sense of energy, exertion, and expression (that is the RDL). At this moment, the low mf RDL delivers a sense of arrival and a settling in the place of the conception and expression in which the track exists. It is common for a track to arrive at its RDL as an important occurrence, but it is not common for it to be a point of arrival that provides aesthetic closure to a track.

Loudness Balance, Musical Balance

The balance of sound source loudness levels established by recording exerts significant influence on the track. The level of loudness of sources and their resulting interrelationships represents an important element of recording—this is loudness balance. Though loudness balance is but one of the recording elements applying influence on the track, it has the potential to prominently shape the content and character of the track.

The recording’s role shaping relationships of sounds is often reflected—to some degree—within loudness balance. Loudness balance situates each source in the mix in terms of loudness; as loudness brings all sound into perception, loudness brings it to be audible and establishes its presence. Observing the actual loudness levels of sources can bring an understanding of the loudness contours of each source, of their loudness relationships, and of the composite texture’s loudness balance. In music settings, loudness balance of instruments and voices (sound sources) is commonly framed as ‘musical balance.’ In earlier writings (Moylan 1992 and 2015) I have used ‘musical balance’ synonymously with what is referred to as ‘loudness balance’ here. ‘Loudness balance’ will be used here to more clearly differentiate this recording element from the elements of music.

Loudness contours of individual sound sources can be notated on an individual or a collective ‘loudness contour graph.’ This can provide a clear way to notate even the subtlest loudness/dynamic changes of individual sources and their gestures, or musical lines. It can also reveal loudness relationships and groupings of sources where they combine to create particular contours. The loudness balance X-Y graph will illustrate the actual loudness levels of sources; the graph can be used to make general loudness observations, or it may be calculated in detail against the reference dynamic level. Either approach may be most appropriate, depending on the goals of the individual analysis. Sound sources are represented by a separate line of the graph, allowing their contours to be mapped as it changes over time. The graph displays loudness as loudness—it does not factor in the influences of timbre, register, or prominence of any other origin. We remember that loudness is the perception of the amplitude of sound as we bring our attention to this element. It is important to remember to hold all sounds in equal prominence, as loudness can easily be distorted by listener perspective and focus. A source in the center

Figure 9.3 Loudness balance graph of the Beatles' "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" from Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967, 1987).

of one’s attention will be emphasized in one’s awareness, and cause loudness judgement to be skewed. Listening for loudness contours, and judging relationships to the RDL does, however, bring one to listen at the perspective of the individual source. Praxis study 9.3 can guide these listening experiences.

Figure 9.3 illustrates the loudness balance of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967, 1987). This graph provides great detail on the loudness shapes and relationships of all sounds against the track’s RDL. Note the designation of the RDL’s placement related to the dynamic areas; the loudness levels of individual sounds are interpreted against that level just as occurred with the program dynamic contour (track loudness contour). The RDL is the same in each graph (observing the same track).

This graph brings the activities of all sources into keen focus, and closely observes their loudness interrelationships.

Not all analyses require this highly detailed data collection, though. A more general assessment of loudness levels might provide adequate insight into tracks. Figure 9.4 illustrates the loudness levels of sound sources in three versions of the Beatles’ “Let It Be.” The sources are identified within the more generally-defined (though closely consistent with traditional dynamic areas) loudness areas ranging from very soft to very loud. These graphs contain general contours of loudness levels of little detail; they provide an impression of the overall loudness level of sources during a section or passage. A reference dynamic level is absent from each version as well; this also contributes to the general nature of these loudness level and relationship observations. A quick glance at these graphs identifies fundamental loudness differences between the three versions, even with observations quite generalized. Much detail could be extracted from these examples, adding to what has been provided here.

The original, single-release version produced by George Martin has a narrow range of loudness levels. All sounds are in the lower half of ‘moderately loud.’ The lead vocal is loudest, except for a short phrase at the end of Verse 1. The background vocals have a similar loudness, to the lead vocal and piano, and is situated between them until the piano increases in loudness at the end of the chorus. The piano’s rise in level at the end of sections is obvious from the graph.

Phil Spector’s version from the Let It Be (1970, 1987) album has clear contrasts. Loudness varies between high ‘moderately loud’ to the upper portion of ‘soft.’ The background vocals passage changes loudness level markedly. The piano retains its general loudness contour, though the chorus level is some magnitude lower in this version. Billy Preston’s Hammond organ resides at a soft loudness in the chorus, removed from all other sources until its level is approached by the backing vocals at the end of the chorus.

The graph for the Let It Be . . . Naked (2003) version makes clear it has the widest range of loudness levels of the three versions. The lead vocal is loudest in this version; just as in the other two versions, it is the loudest within the track. The background vocals are louder in this version than in the others, and the general loudness contour of the piano is slightly modified in the chorus. The Hammond organ is present throughout all sections graphed; though it is extremely soft and at times barely present, it has a distinct loudness contour.

Performance Intensity

Contrasting performance intensity with loudness balance allows the analyst to observe the impact of the mix on the performances of sources. Here, loudness contrasts with timbre instead of working in synergy. Loudness changes not accompanied by timbral changes emerge, and the reverse occurs as well, as timbres remain stable while loudness is altered. This contrast will often provide information on the relationships of sound sources to the overall loudness level of the track (program dynamic contour).

Figure 9.4 Generalized loudness balance graphs of three versions of the Beatles' "Let It Be."

Performance intensity reflects the qualities present when a voice or an instrument is recorded; it is reflected in the timbre of the sound source. Performance intensity is the timbre of the instrument resulting from the levels of physical exertion, energy, expression, performance techniques, and any other timbral qualities related to performance present in the sound and the performance when it was captured (recorded) (Moylan 2015, 450).

The loudness level that established performance intensity when the source was recorded is transformed within the mix process. This allows performance intensity—and its expressive content—to be a separate percept in the track. This dichotomy separates reality from the crafted world within the record; this is an inherent trait of popular music recordings. The timbre of performance intensity is often used aesthetically to carefully shape the performance itself. In this way it is used to enhance the drama and expressions of the track, and for many other purposes. For example, sounds of low performance intensity often appear at higher loudness levels in the mix than their timbres indicate; this is especially common within vocal performances, where a whispered word can appear loudly in the track. In expressing lyrics and the musical line, a lead vocal can vary in performance intensity considerably and often—sometimes within a word or a syllable. The voice—“full of concrete meaning that is not conveyed through lyrics is to be found in all forms of musical expression, but in recorded music, precisely because it is recorded . . . the effect is especially discernable” (Lefford 2014, 44)—clearly illustrates the significance of performance intensity to shaping interpretation by performers and listeners. Performance intensity is often the primary carrier of musical expression, and also of the drama delivery and the shaping of meanings within the lyrics. It can create and carry the level of urgency in the track and establish a sense of tension or of ease.

The levels of performance intensity are interpreted by listeners by observing timbral qualities as they relate to physical exertion and expression. Denis Smalley (2007, 39) notes: “[O]ur experience of the physical act of sound making involves both touch and proprioception—the tensing and relaxation of muscles in relation to all types of body movement.” This experience can be one of observation as well as participation. A listener’s prior experience with and knowledge of the particular instrument’s timbre, as well as their abilities to remember and match the timbre in a state of normalcy, play central roles in this interpretation, and its relative accuracy. The deeper the experience and prior knowledge, the more likely the listener will successfully and accurately recognize the instrument’s performance intensity through perceived timbral qualities. In absence of experience, this interrelationship of timbral quality and performance intensity may have its “content . . . simply assumed, or even invented, by the listener” (A.F. Moore 2010, 259). No matter the accuracy of the percept to the actual act, performance intensity contributes substantively to a listener’s interpretation of important aspects of the track.

The threshold level that separates expending and restraining energy—the transitions from force to resistance as discussed in Chapter 3—is a reference for calculating performance intensity. At this level, resting between mp and mf, performance intensity (and source timbre) is in a state of normalcy for timbral characteristics, where the timbre is not altered by the energies of performance. This level of effort can theoretically be sustained indefinitely. In “Burnt Norton” from Four Quartets, T.S. Eliot (1943, 15–16) called this idea “the still point”; his poem describes this “still point of the turning world” as being “neither from nor towards ... neither arrest nor movement . . . neither ascent nor decline . . . except for ... the still point, there would be no dance, and there is only the dance.”

This “still point” provides a reference to allow loudness related to the listener’s perception of body movement’s role in sound making to be calculated. Embodied music cognition tends to recognize music perception as based on action—those of the listener body movements, and perception of kinesthetic properties and musical gestures involved in creating the sounds of the performance (Zbikowski 2011, 181–190).

Performance intensity in itself can produce directed motion in a line. The urgency of performance intensity’s expression and perceived actions of its physicality can create motion and tension in music, and in subdued expression it can create calm, ease, and repose, and thus mitigate all but the slightest tension; this is not a duality, but rather a continuum that may establish many states between the greatest tension and most urgency imaginable, and the slightest motion of ease and a most minimal sense of tension. Performance intensity can communicate urgency and energy, drama and expression, directed motion and stillness, tension and release, exertion and restraint, and more. Changes can be extreme and fast, subtle and gradual, but all contribute character and substance to sound sources and their materials—all are embodied in the timbre of the sound source and its invisible performance gestures. Performance intensity does much to shape the character of timbres and the affects of their delivery, and define the qualities of individual performances and the delivery of their musical idea.

A confluence of all domains and many of their elements can be found within performance intensity—as timbre, musical lines, and perhaps lyrics blend into one gesture. Performance intensity— and all that it carries—is an important aspect of performances in the track (Moylan 2015, 323).

In the context of the track, performance intensity may be accompanied by loudness changes, but not necessarily. Timbre can change without loudness changes, and performance intensity is reflected in timbre much more than loudness. These are controlled separately in the mix process.

Performance Intensity and Loudness Balance Graph

Figure 9.5 is a performance intensity and loudness contour graph. This graph is uniquely suited to the analysis of recorded performances, and can reveal a wealth of pertinent information.

Performance intensity is notated on the upper tier of the X-Y graph, charting the dynamic levels and contours of each source’s original performance. The timbres of sources are not related to the reference dynamic level; rather their intensity is calculated based on their timbre and expressive character. The lower tier of the graph provides the loudness balance of sources; the loudness levels of sources are calculated relative to the track’s RDL. Contrasting performance intensity with loudness balance, one is comparing two separate elements against the same timeline—the interaction of implied loudness of timbre and actual loudness in the track illustrates a confluence of the recording elements as well as their independence. The graph allows direct comparison of two different states of the same sound sources, as they change over the duration of the example.

Performance intensity and loudness contour graphs may contain all sources, or a selection of sources of significance to an analysis. When needed, a single source might be observed through this approach. The level of detail of data from both performance intensity and loudness balance can also be adjusted to reflect the needs of an analysis, from a significant attention to detail to general impressions.

Figure 9.5 provides much detail of contours and levels in both tiers. The graph could have greater detail, though. Subtle changes of timbre in the vocals and in several instruments are not contained here. In examining the two tiers of Figure 9.5, one can immediately recognize the disparity in levels of the Lowrey organ, as it is much louder in the mix that its performance intensity suggests. Comparing the two tiers, one can determine how sources deviate from their original levels, and just how far the loudness balance has strayed from the original

Figure 9.5 Performance intensity and loudness balance graph of the Beatles' "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds," Yellow Submarine (1999).

performances of the parts; the loudness relationships suggested by the timbres of the original performances are represented in the ‘performance intensity’ tier.

Figure 9.5 presents the Yellow Submarine (1999) version of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” graphing both performance intensity and loudness balance. It contrasts with the original Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band version in Figure 9.3, which provides the loudness balance of this same sections as 9.5. These two versions were created from the same source tape, with the same performances— allowing the opportunity to bring our attention to clear differences of loudness balance, loudness levels, and loudness contours from the same performances. Comparing the two versions of loudness balance allow us to recognize that they have slightly different reference dynamic levels, a product of their different mixes (loudness level shifts, plus changes in other recording elements); both RDLs are in the upper portion of mf, with the Yellow Submarine version being slightly higher. While many loudness levels of sources have similar relationships between the two mixes, some sources have distinctly different loudness levels (such as the vocals in the chorus) and contours (observe the Lowrey organ in the introduction). Notice the shaping of the bass line; more nuance of changing levels is present in the original version. Numerous other differences can be observed from the graphs, and from listening to the tracks.

THE CONFLUENCE OF ALL THE TRACK CONTAINS

Confluence acknowledges the interdependence of all domains, all of their elements, and the performance. There is a complex interplay—as we have examined in materials, perspective and structural levels, aesthetics and affects—where we find no single thing dominates the track at any moment, though anything may be most prominent within (or dominate) our attention and interpretation at any moment. This interdependence within the track establishes a tapestry of all that is present— an intricate web of interrelationships and sound qualities that is an inner dimension of crystallized form. This confluence can be extraordinarily intricate, and yet appear unadorned, as Albin Zak has observed:

In the recording process, the mix establishes this confluence. It is in the mix process that recording elements are largely defined, blending and delineating pitch/frequency, timbral, spatial and loudness attributes. The process of mixing also blends the individual performances of all sources; it provides each source with a spatial identity and final alterations of timbre. The performances of musical materials and lyrics are shaped by recording elements within this process, establishing the fundamental qualities of the final track—qualities that provide the track with a level of distinction. The mix process occurs at the basic-level of sound source and at the composite level that compares them as equivalent and equals, though its confluence influences relationships of all elements at all levels of perspective. The mix shapes and blends even the subtlest aspects of each element of each domain into a sonic tapestry that ultimately manifests as the overall timbre of the track and the track’s spatial identity.

The mix manifests the confluence of the track. It is also a metaphor for the confluence of all the qualities, proportions, character and expression the track contains. Elements lose their individuality as they blend into gestures and materials, aural images and aural events, and a rich and complex texture. The acoustic wave (the result of all of the sounds of the track) that arrives to us (slightly differently at each ear)

There is good reason we often have trouble making sense of what we hear in the record; confluence establishes a rich and multidimensional texture that can blend sounds so they are no longer distinguishable.

Prominence Emerging from Confluence

The mix establishes a balance of all parts within that complex texture. From that balance, any sound or element may emerge to be more prominent than others. As we learned above, prominence is established by listener attention. Attention is drawn to what stands out from all else—this exists at all levels of perspective, comparing sounds of sources, observing the elements within sounds or musical lines, observing the interactions of musical materials, hearing a text emerge from a musical fabric, and more. Albin Zak (2001, 157) significantly notes that “prominence is perceptible only in relationship. That is, to assess prominence we need a frame of reference.” A frame of reference exists from the materials and elements within the track, whereby some ideas emerge as more significant, and others fall into other roles; sounds can also emerge because they are interesting in some way, or simply discovered and brought into the center of one’s attention. From the latter, we might begin to understand how prominence can be personal—what emerges from the texture for one person (and their listening interests, skills, sensibilities, experiences, etc.) may not emerge for others, and certainly will carry some level of individual interpretation.

Allan Moore and Albin Zak both use the term ‘prominence’ in a manner that contrasts with this writing (see earlier this chapter). Zak states: “[R]elations of prominence are analogous to ‘depth,’ among Massenburg’s four dimensions of the mix. They impart impressions of proximity and emphasis along with whatever associations these may have” (ibid., 155); this points to Massenburg’s blending of the terms proximity (depth) and prominence. Allan Moore (2012a, 31) uses the term ‘prominence’ to represent “sounds . . . more (or less) distant than each other” referring to perceived proximity or distance, the second dimension of his soundbox.

I use the term ‘prominence’ as a perceived emphasis of one material (element, domain, etc.) over another that is determined from a manner of attention, and from a direction of focus. I use the terms and concepts of ‘depth’ and ‘distance’ as dimensions of physical space—dimensions one might physically measure, or perceive, and/or interpret depending on context. The percepts of depth and distance are distinctly separate, and both are removed from prominence, which I approach as a manner of interpretation that may emerge as evoked from any element, sound or material.

When Albin Zak (2001) discusses ‘prominence,’ he approaches the concept more broadly, thereby touching upon several key concepts that are relevant here. First, he clearly identifies depth as existing at many levels of perspective, from the overall texture to the individual event—a central consideration related to confluence and the mix that applies to all elements. Next, he also extends his use of the term ‘prominence’ toward engaging the ways tracks reveal and emphasize elements and materials; especially significant is his recognition of the “multifaceted nature of prominence perception” (2001, 156). He makes it clear ‘prominence’ is distinct from ‘loudness;’ though prominence might be established by loudness, it is only one facet that might influence the impression. Prominence may also be established by timbre, its level of diffusion in the mix (environment quality), ambience, sense of distance or location in the stereo field. This acknowledgement of the multifaceted nature of prominence is significant. Sounds will emerge from the confluence of the track at all levels of perspective, and within all domains—including the confluence of recording elements and the confluence of all that the track contains. These concepts support the roles of equivalence as a factor in the potentials of any element to have significance, and in bringing attention to prominence perception (Moylan 2015, 320–321).

A sense of shifting perspective—intentionally shifting the focus of attention from one level of detail to another—allows prominence to be recognized as a matter of context, relative to its surrounding materials and elements. Eric Clarke (2005, 188) describes:

A sense of control develops as attention is deliberately and clearly focused to various perspectives, various domains, various elements, and so forth. With this sense of control, a perception of prominence that is the result of context rather than bias has the potential to emerge. The analyst might then be able to choose whether to seek “what is most prominent within the texture” or “what appears to them the most prominent based on their own sensibilities”; the deliberate choice is what is important here. One choice allows the analysis to be based on (or at least emphasize) content within context of the track and within a culturally bonded interpretation, and the other emphasizes personal interpretation—of course, a continuum of shadings exist between these two poles.

Confluence of Recording Elements

The interrelationships and interdependence of recording elements manifest within the confluence of the mix, as each individual recorded performance (or track) is combined and mixed with others. Richard Middleton (1990) has framed this process as ‘polyvocality’:

This section examines ways data collected from several recording elements can be displayed to allow their individual traits and their interactions to be observed. What is offered is far from exhaustive, but can lead the analyst to determine how to most suitably explore elements within individual tracks. The most significant difference in these approaches to comparing elements lies in the factoring of time into observation methods. Some recording elements in some tracks are substantially fluid and temporal, changing over time. Other elements may be largely or completely static or stationary, their qualities fixed throughout a track or within sections; non-temporal graphs or diagrams bring a visual representation of the data of these elements. The temporal nature of any recording element within any track may establish surface rhythms aligned with the metric grid—though this is uncommon, especially an element like environments; elements establish their own pacing and morphology (changes of quality) within individual tracks, and also at each level of perspective.

The number of sources examined in diagrams, graphs or within any process might range from all sources present to a smaller number of select sound sources; a single source could also be graphed in all of these forms, allowing it to later be examined in great depth. Timelines for graphs might range from the entire track, to major sections, or perhaps single measures or more extended phrases. The span of time represented by illustrations and diagrams might be defined similarly.

Temporal Graphs for Comparing Recording Elements

Interrelationships of recording elements can be observed by comparing the observations of elements. The juxtaposition of loudness balance and performance intensity X-Y graphs discussed above allowed those elements to be observed simultaneously, as they evolved temporally over the duration of the example; changes of levels (either general or in detail) could be displayed in their magnitude and at the time of their change(s). Time marks the place (or moment) of change, and comparing these places of change represents rhythm.

Graphing two or more elements against a common timeline might display the elements’ data so as to allow their interrelationships to emerge more visibly—in other tracks this effort might yield less richness.

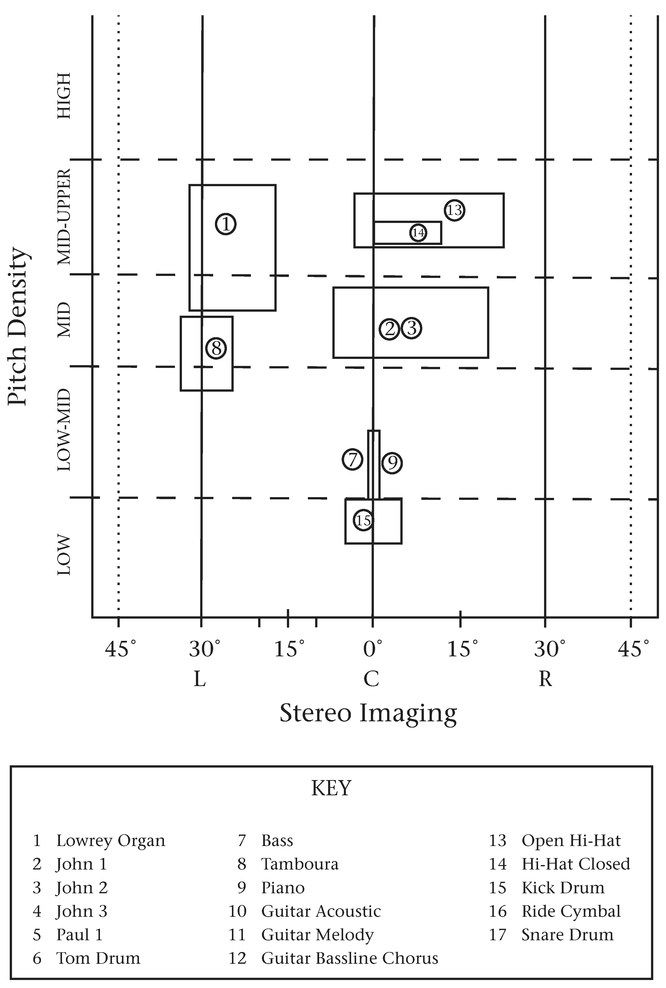

This approach can be used similarly for any other combination of two elements to be compared at the same level of perspective. At the perspective level of the composite texture where the interdependence and interrelationships of elements manifest, we have identified five qualities of this texture:

- Pitch density

- Loudness balance

- Performance intensity

- Stereo imaging (image positions and sizes, transferable to surround sound)

- Distance positions

The reader may notice host environments and timbre are omitted from this listing. Timbre and host environments do not function directly at the composite level, interacting with others; they function most strongly at the basic-level of defining the character and content of sources into an identity (“an acoustic guitar in a small hall with vaulted ceiling”) or at the overall texture (as timbral balance and holistic environment). These more complex percepts are comprised of several elements from this list functioning at a lower perspective.

These five qualities may be coupled into ten (10) X-Y graph pairs—ten ways the qualities of the composite texture might be observed in groups of two. Among the possible permutations, interesting evaluations might emerge from observing the following pairings at the perspective of the composite level, plotted against the same timeline:

- Distance positions and stereo imaging X-Y graphs

- Stereo imaging and pitch density X-Y graphs

- Performance intensity and pitch density X-Y graphs

- Loudness balance and distance positions X-Y graphs

- Loudness balance and pitch density X-Y graphs

In addition to the coupling of performance intensity and loudness balance offered before, other dual combinations of elements may be desirable, as they hold potential to generate pertinent observations

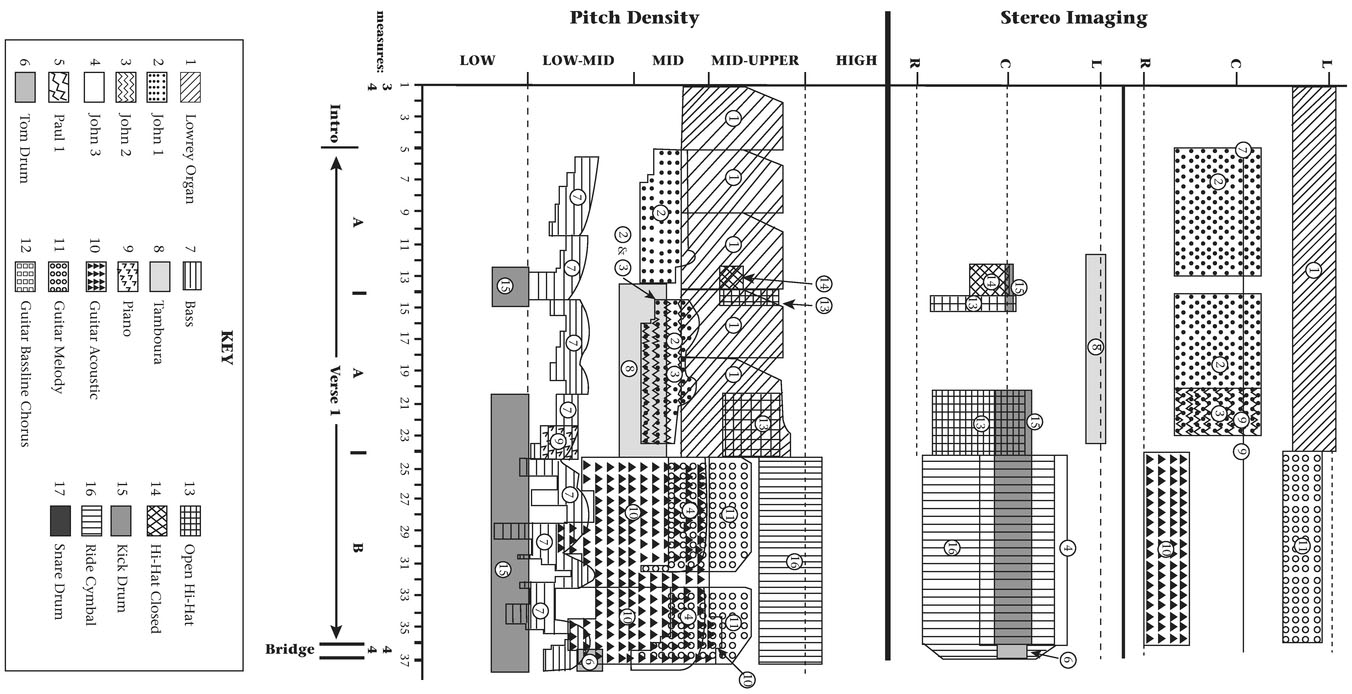

Figure 9.6 Temporal X-Y graph comparing pitch density and stereo imaging against a common timeline; from the Beatles' "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds," Yellow Submarine (1999).

for an individual track (or section thereof). These other combinations are (1) pitch density and distance position, (2) loudness balance and stereo imaging, (3) performance intensity and stereo imaging, and (4) distance position and performance intensity. Some graphs are more workable than others, and the value of any graph is related its usefulness or appropriateness for an individual track; a graph’s usefulness is based on the content of an individual track, the goals of an analysis and the intentions of the analysist. All temporal graphs can allow subtle changes to be illustrated and observations can be detailed, or they may be approached observing more general values.

Examining combinations of three or more elements might progress similarly at the composite texture, illustrating the various elements of basic-level sources. Figure 6.2 illustrated loudness balance, stereo imaging and distance positions for four sources against a common timeline. Any combination of elements may be examined in this way, so long as observations remain at the same level of perspective. Returning to the five composite texture qualities listed above, there are ten (10) possible combinations of three qualities, and five (5) possible combinations of four qualities that could appear on a single graph, on separate tiers and against a common timeline.

The combination of pitch density, stereo image width and location, and of distance position is one of the ten possible combinations that could comprise a three-tier X-Y graph against the same timeline. This combination is the same as the soundbox (explored later).

Non-Temporal Graphs and Diagrams for Comparing Recording Elements

Table 9.3 Possible recording-element combinations of three (3) and of four (4) elements that may interact and/ or establish inter-dependence within the composite texture.

Certain combinations of elements may also be charted as opposing axes on the same X-Y graph. Some combinations of elements are better suited than others for illustrating data. Figure 9.7 plots the stereo image size and position and the pitch density of several sound sources, positioning the sounds in perceived lateral space and by frequency/pitch content—what some refer to as “spectral space” (Smalley 2007) or “pitch space” (A.F. Moore 2012a, 31). This juxtaposition works visually, whereas graphing other combinations from the ten pairings described above may not be as successful—for instance, materials in a graph of performance intensity on the X-axis and loudness level on the Y-axis may be confusing. These two axes are capable of presenting these two source attributes with as much precision and accuracy the analyst wishes to seek; this graph allows considerable detail to be observed for these two dimensions of the “soundbox,” described in the next section.

Figure 9.7 Non-temporal X-Y graph comparing pitch density and stereo imaging; the Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” Yellow Submarine (1999), 0:00–0:31.

Subtle changes or aspects such as small gradations of size, location, etc. are often significant to recording elements, and are often temporal in some way. All subtle changes and qualities have the potential to be significant to the track. An analyst choosing to use non-temporal graphs or diagrams may be forced to omit or condense details that cannot be incorporated into the format; changing formats for displaying data may be required if the data of the track cannot be clearly represented.

As these graphs are non-temporal (do not change over time), materials or elements that change over time are typically generalized into a single image. Elements that exhibit changes are difficult to notate, or illustrate, and might be generalized similarly. It follows that these graphs are inherently less detailed, imprecise to some degree (depending on the track and materials), and represent some span of time.

As time is not incorporated into these illustrations, the time period represented needs to be identified. These graphs (or illustrations) represent snap shots of time, or defined durations within which the graph’s content is present. This time period can represent syncrisis time units (Tagg 2013, 385) of an extended present, an integrated auditory scene (Bregman 1990) of some duration less than a syncrisis unit or extending beyond the window of ‘now sound,’ a structural song section (an appropriate division for numerous elements of many tracks), or a generalization of an entire track. Any time span appropriate to the element(s) and to the track may be represented here. Typically, the longer the time span the more likely the illustration contained missed details, as the track’s subtle information is increasingly absorbed into an overall impression.

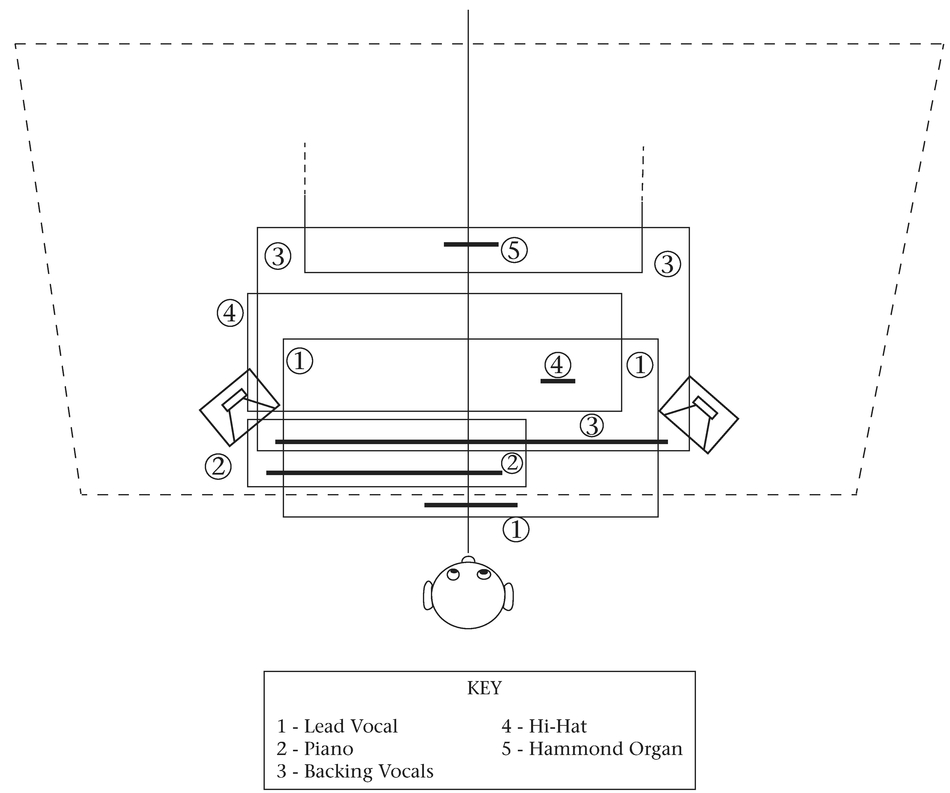

The sound stage diagrams introduced in Chapter 8 are examples of non-temporal illustrations. Those diagrams represent defined periods of time; these may be considered as ‘scenes’ (Chapter 8) that take place over defined periods of time. Sources placed on those diagrams can be precisely located on the scaled sound stage (see Figure 8.9), for image location and width boundaries as well as distance position; those diagrams incorporate scales allowing detail to accurately place sounds.

Sources are located with less precision on the proximate sound stage (see Figure 8.8), where lateral and distance axes are not scaled. Image boundaries and positions are more generalized, though their relationships with other sources and the listener position are apparent. Figure 9.8 uses this proximate sound stage to localize sources in lateral size and distance from the listener point of audition, and also to provide an illustration of the size of source host environments, and their relationships.

Thus, the perceived depth of the sound source plus their individual host environment might be incorporated into the proximate sound stage, providing additional detail to the depth of the sources and of the sound stage. This allows source and environment placements to be conceptualized on the sound stage, though not placed in exact positions. Sources can be localized with proxemics (with as much detail as needed) though environment size is an interpretive approximation of the size of the space and the distance of the source from the front of the space and its rear wall. Some of these qualities are not present in artificial spaces. Sizes and locations of host environments are determined largely by comparing one sound to another, one space to others, etc. The non-scaled placements of sources within this format is more appropriate for these percepts which cannot be placed with proxemics or against a scale. The increments of space used to divide the scaled sound stage do not conform to these percepts; while one can identify precise widths and depths of spaces, we do have a sense of the distance of the source from the boundaries of the space, and can use that sense to assess the relationship of the source to the geometry of its host environment. Figure 9.8 demonstrates placements of sources plus their host environments on a sound stage—stated differently, this non-temporal figure allows three elements (stereo imaging, distance location, host environment size) to be illustrated in one place, and for comparisons to emerge. The track’s multiple spaces, the interactions of spatial simultaneity (Smalley 1997, 124), and the interrelationships of host spaces to the holistic space might be observed aided by this illustration.

The Soundbox and Other Approaches to Observing Multiple Recording Elements

The approaches discussed here—including the soundbox and various sound stages—mark a transition from data collection and display, toward and engaging the potentials of the elements in shaping the record (we will seek to retain clarity between the acts of collecting or observing data, and of evaluating it). Each offer guidance to access and recognize the contributions of recording elements to the track, and the interdependence of elements as each contributes to confluence. The acts of examining and of recognizing contributions of elements are the evaluation and conclusion processes—processes that will be explored in detail within Chapter 10. Only a few of these approaches below offer ways to illustrate or notate elements. While illustration and notation (of all sorts) is rife with issues we have discussed before, it holds benefits of collecting, refining, visualizing and holding data; as observation progresses, it is simply impossible to accurately hold all information in one’s mind.

Figure 9.8 Proximate sound stage of “Let It Be” (Past Masters, Volume Two, 1988) 0:00–1:01. Diagram illustrates sound source image positions and size, outlined by the widths and depths of their host environments.

The general qualities of the proximate sound stage have some similarity to the soundbox (briefly discussed in previous chapters). The soundbox contains the dimensions that numerous scholars engage when discussing tracks: stereo field, depth of sound stage and frequency range.

Allan Moore (1992) offered the soundbox as an approach to illustrating some of the primary elements of records; while in a way that has some similarity to sound staging it was devised quite separately. It is also distinctly different. The soundbox “is a heuristic model of the way sound-source location works in recordings, acting as a virtual spatial ‘enclosure’ for the mapping of sources . . . locations can be described in terms of four dimensions. The first, time, is obvious” (A.F. Moore 2012a, 31). The other three are the stereo image, distance (which he identifies as “perceived proximity of aspects of the image to ... a listener”) and “the perceived frequency characteristics of sound-sources” (ibid.). The soundbox is “almost like an abstract, three dimensional television screen” (Moore & Martin 2019, 149), positioning sound sources in frequency/pitch range (as in pitch density, above), in stereo positioning and image size, and in perceived proximity to (distance from) the listener position; using terminology offered within this writing, it combines stereo imaging, distance positioning, and pitch density. Like sound stage diagrams, the soundbox is at the perspective of the composite sound; it illustrates strands of instrumental timbre “conceived with reference to a ‘virtual textural space,’ envisaged as an empty cube” (ibid.). Fourth dimension of time represents a span of time, much like sound stages; illustrating changes to source positions in any of the three dimensions requires a new soundbox. It is challenging to make motion of images (changes of positions) clear in any illustration that does not incorporate a timeline— including the soundbox.

Allan Moore and colleagues have applied the soundbox to numerous tracks pursuing a variety of goals,6 including a taxonomy study (Dockwray & Moore 2010). The soundbox can convincingly illustrate the relative placement of a moderate number of sources (adequate for many tracks) within a conceptual three dimensionality of space. It combines percepts of two perceived physical dimensions and one metaphorical conception of the“‘highness’ or ‘lowness’” of pitch/frequency (Doyle 2005, 27). What the soundbox loses by way of precision of displaying data, it often gains in establishing a readily identifiable three-dimensional visual representation of sources. The similarity of the soundbox to the visual approach of representing sound sources as circles used by David Gibson (2005) has been acknowledged (Dockwray & Moore 2010, 224–225). Soundbox diagrams use simplified representations of specific sound sources—images of instruments and voices—morphed to occupy the three-dimensional space of the sound.

It should be clear the soundbox examines individual sound sources at the basic-level, as does the sound stage; this perspective allows comparison of sources at the level of the composite texture as well. These levels of perspective are the basis of approaches offered by the following scholars as well. As we have engaged many times to this point, the same percept can be defined differently on different levels of perspective. The audible pitch/frequency range (divided into registers) that I use to chart “pitch density” on the composite level (and timbral balance in overall texture) is defined as ‘register’ or the “height” of a sound by Allan Moore (2012a, 31) for the vertical axis in the soundbox. Lelio Camilleri (2010, 202) conceives the audible pitch/frequency range as “spectral space”; it is “height” to Anne Danielsen (2006, 52) and “frequency spectrum (height)” to Albin Zak (2001, 144); Jay Hodgson (2017, 220) approaches the audible pitch/frequency range as a “vertical plane.” Considering a percept from a slightly different conceptual angle—perhaps as an object experienced in crystallized form—can change how one perceives the concept (element, percept, or confluence) without altering its substance; if solely for this reason, each of these approaches (and those of others) holds value for our analyses. There are other reasons to be sure; each considers similar aspects in unique ways, and some explore other dimensions of tracks. These approaches have some inherent differences, but largely the same percepts engaged from different angles.

Lelio Camilleri (2010, 201) approaches the interaction of recording elements as a three-dimensional “sonic space” “to indicate the space in which the piece unfolds in recorded format.” The three dimensions are localized space, spectral space and morphological space. Localised space is the area wherein sounds are placed in stereo and mono, and includes depth, position and motion; this reflects two axes of the soundbox and also of the sound stage. Camilleri offers: “[T]he spectral content (timbre) of sound plays a relevant role in the overall perception of space. . . . the notion of spectral space . . . is metaphorical since there is no such physical space” (ibid., 202). Within the spectral space [the pitch/frequency range of the track], the spectral content of the sounds used can establish experiences of saturation or emptiness within the space; in addition, Camilleri acknowledges the perspective of spectral space at the perspective of overall sound (timbral balance): “[T]he combination of the spectral content of sounds and their disposition can accentuate the various sensory experiences to be had from listening to the overall sound structure” (ibid.). The third dimension is morphological space, as sound unfolds temporally to develop the shapes of sounds, and perhaps evoke motion and a sense of direction; this can be at the perspective of sound source timbre, though its implications can manifest at all structural levels if one remembers the equivalence of elements at all structural levels, and timbre’s central role as a recording element.

Albin Zak (2001) views the confluence of recording elements as a four-dimensional space, supported by incorporating concepts of mixing music offered by George Massenburg. The approach “highlights the interactive nature of the relationships among individual elements and larger composites—artifacts and gestures—and points to the ongoing shifts in perspective that a record makes available through its manipulation of ‘four-dimensional space’” (Zak 2001, 144). Three of the dimensions are familiar: the stereo soundstage (width), the frequency spectrum (height), and “the combination of elements that account for relations of prominence (depth)” and the “fourth dimension is the progression of events, the narrative or montage” (ibid.). The fourth is temporal (as also identified by A.F. Moore and Camilleri), though it seeks information on all levels of perspective and acknowledges the unfolding of drama, structure and simultaneous, perhaps unrelated materials, elements or sounds. His use of ‘prominence’ was discussed earlier.