Chapter 2

Overview of Framework: Principles and Concepts, Materials and Organization

This chapter adds detail to the three domains (music, lyrics and recording), and will engage several of the framework’s central principles and concepts in greater depth. The three domains are each examined for their unique syntax and language, and the materials they may generate. The various functions which elements and materials might assume will follow. Principles and concepts of the framework are clarified by examining:

- Perspective

- The delineation of the various concepts of form

- The relationships of form and perspective to structural hierarchy

- Listening with intention and attention

The framework’s guiding principles of each record’s uniqueness and of equivalence are imbedded in the discussion of domains and syntax. The principle of perspective is investigated as the concepts of form and structure are distinguished. Here the passage of sound in time as events and the stilling of sound and time formulating sound as object are contrasted; this distinction is clarified by the concepts of shape and movement.

Listening with intention and attention is the fourth principle of the framework. Accurate listening is central to successfully perceiving the qualities of the record; the confluence within records easily obscures its individual elements as well as their subtle features. The highly personal nature of listening brings challenges to identifying universal information and understanding personal bias and our unique perceptions and understandings. Listening with intention (supported by knowledge and sense of awareness), cultivating attention, and listening without expectations can bring the listener/reader to hear and recognize the record’s qualities—those qualities that are actually present—in ever-greater precision, clarity and detail.

THE THREE DOMAINS: MUSIC, LYRICS AND RECORDING

As briefly discussed in Chapter 1, the recorded song is comprised of three streams of distinctly different information: the domains of the music (and its performance), of the text (lyrics), and of the sonic qualities of the recording. These three realms form the materials of the record—and the record’s content, its message and meanings, and its expression. They merge in confluence, blending synergistically into a single multidimensional sonic tapestry.

Despite this intricate confluence, the three domains exist individually with their own unique elements and characteristics, and may function independently as well as in tandem with other domains. Each of the three domains contributes its individual materials and imparts a characteristic imprint on the track; each may be created independently, though they may be crafted to complement another or both others. On some level, they are each crafted and shaped individually, in their own distinct voice.

We engage all three domains within the recording analysis process, seeking to understand their materials and organization, and their contributions to the recorded song. We examine how they interact to form intricate relationships—interactions that add significantly to the overall depth and complexity, richness and subtle detail of the song. An emphasis on the elements of the recording lights an examination of how the ‘record shapes the song.’

The content of each domain is shaped by its elements. Their elements function with purpose, and carry the potential to contribute fundamentally to the character and content of the song. Next is a brief outline of the elements of each domain, to set the context for the discussions that follow. These elements are explored more deeply later, in chapters dedicated to each domain.

Elements of Music

Elements of music in the record are more than the traditional score, or even the live performance and the score; the elements represent a specific performance, captured in a specific time and place. The performance is intrinsic to recorded song, and embodies the musical elements. Here the music and the performance have potential to contribute equally to the musical idea. Most significantly, they combine collaboratively into a single sonic and musical statement.

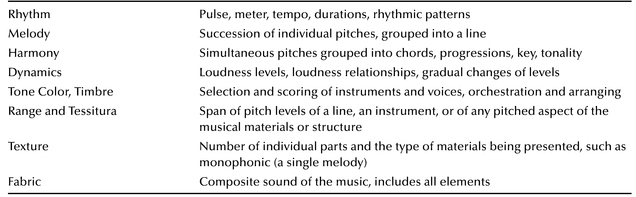

The traditional elements of music in the ‘music’ domain are shown in Table 2.1. In much of recorded song, it has been practice to engage music with a focus on pitch relationships—with successions of single pitches forming melody and groupings of simultaneous pitches creating chords, thereby enacting harmony and tonality. Rhythm manifests the temporal to become integral to and to propel melody and harmony through organized time. Traditionally pitch-based elements and rhythm have been enhanced by dynamics and timbral constructs of instrumentation and arranging, and tessitura and range. Ultimately all coalesce into states of texture and fabric.

Table 2.1 Elements of music.

Melody and harmony are commonly examined in traditional music analysis. The other elements found here are typically less often evaluated, and appear less explicitly (if at all) in the musical score. These will receive detailed attention alongside melody, harmony and rhythm as we examine them within recorded song.

In the approach presented herein, all elements are examined for their contributions to the music’s character, flow and substance. Each element is examined with equal attention, and all elements are examined for their place in the interrelationships that are formed in many ways and on many levels, as a complex web of the interaction of elements is integral to even the simplest music.

In contrast to traditional, score-based analysis processes, analysis here will emerge from the sounds of the music itself; evaluated directly from the record, where the song is complete.

Subtleties of music performance are integral to the musical materials, musical expression and other musical qualities of the record. In the record, sonic aspects of the performance are elements as well. The energies and sounds of performance meld with the ideas of composition to create a larger experience—especially once transformed by recording processes. Albin Zak (2001, 51) recognizes this as he articulates:

The performance is about intensity and expression, as much as any other element; these are present in the nuance of timbre or sound quality most strongly, but are also reflected in other elements, such as dynamics or subtle flexing of time, silence and pitch.

All of the sound qualities of musical performance blend into the substance of the music. They are woven into the complex tapestry of the record, just as fundamentally as the traditional elements of music. These performance characteristics include a “flexible molding of pitch, rhythm and timbre” (Winkler 1997, 186) that establish fluidity of the line, and considerable added substance. This substance becomes inherent to musical material; it brings the performance to be inseparable from the composition.

To not study the performance, then, is to omit significant substance as well as the music’s living experience, diminishing full understanding of the content of the record. Our approach to understanding the music domain must extend to encompass both musical materials and their shaping by music performance, and acknowledge their inherent contributions to the record. Though not a simple undertaking, the dimensions and qualities of the performance are part of the analysis of the record’s ‘music.’ Every detail is part of the whole; every subtlety of the captured performance shapes the musical idea and the musical experience, though not momentarily as in a live performance but in perpetuity as a recording. Following and examining this detail, so important to the music, is rife with challenges; our music notation system is not designed to effectively depict this information, and our ear has a tendency to distort, simplify or ignore details of what we are hearing in order to allow a passage to conform to our limited notation system. We will work to address this matter; as “those elements which listeners tend to find most interesting in popular music [records] and which most nearly capture the music’s particular strengths (rhythmic and pitch nuance, texture and timbre) are impossible to notate accurately” (Moore 1997, x), a window into understanding these materials is needed.

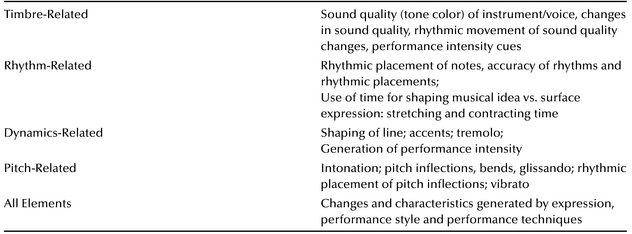

Table 2.2 outlines some of the elements generated by a musical performance.

Table 2.2 Elements generated by music performance technique and expression.

| Message and Story | Theme and subject; narrator and protagonist; Voice and persona; story and narrative; Figurative language devices; References to external sources |

| Structure | Stanzas; lines; patterns and relationships; structural devices. |

| Sound: Timbre, Rhythm, Pitch and Dynamic Inflection | Word sounds and patterns of sounds (such as rhyme); Rhythms (word, line, patterns between lines and stanzas); Diction; Performance techniques and qualities |

Lyrics and Text

Even the ‘unrecorded’ song contains much more than music. Lyrics provide a core dimension of the song, and are readily recognized as equal in significance to the music (and at times more so). From earliest known songs, the lyrics and the music interact synergistically and establish a larger whole; generating great richness of interrelated and complementary materials, communication and expression for the song.

Typically the song’s music provides a platform upon which the story, theme, narrative or drama of the lyrics unfold. The text generates the song’s message and communicates its meaning. As the vocalist delivers the lyrics, the persona of the storyteller is revealed; the performer and the lyrics become enmeshed; a myriad of performance aspects enhance and enrich each sound of each word to further the presentation, drama and expression of the lyrics. The text communicates the theme, and defines the song’s character; it creates motion in time and a sense of intrigue, and it provides the narrative of the song. Lyrics may contribute strongly to the song’s movement in time, through time, or as shifting time, and may present a message of direct simplicity or interwoven complexity.

Lyrics also generate sonic qualities when they are sung. Timbral sound qualities and rhythmic patterns, tonal inflection and stress emphasis points are integral elements to the lyrics. Structural organization of sounds, theme and story, concepts of delivery and persona provide additional elements. Great richness of ideas and sounds, word play and meanings, expression and contemplation, and much more may be instilled in the text.

Table 2.4 Elements of the recording.

In short, lyrics provide the message, sonic and the structural elements in the text domain. These will be examined in Chapter 4.

Elements of Recording

The recording process and reproduction medium of the record impart sound qualities and sonic dimensions to the record (Moylan 1992). This creates the elements of the recording—sonic qualities that are unique and distinct dimensions of the recorded song.

These elements are condensed in Table 2.4. The elements’ qualities and relationships shape each track uniquely, just as each song’s music and lyrics establish it as unique. The elements of recordings transform, enrich and enhance musical materials and the lyrics; they may also provide core substance to the song (Moylan 2015).

Some elements—such as dynamic contours, pitch areas, timbral balance, and others—are conceptually linked to music and music performance elements; while associated with music-related elements, these elements function differently and appear in different dimensionalities in recordings. Other elements such as spatial properties of lateral location, distance and environments are elements that provide qualities that clearly delineate the uniqueness of records, and the unique experiences of recorded music.

These interactions establish a rich set of relationships where elements may reinforce one another, may contrast with or complement others, may balance or may delineate any of the other elements. In much the same way as traditional musical elements interact to create larger concepts like implied harmonies in melody, the elements of recordings interact to establish larger concepts such as the sound stage. Chapters 6 through 9 will detail these elements.

THE LANGUAGES OF DOMAINS

A language is a system of communication. Most often we conceive ‘language’ to be human communication related to linguistics—perhaps existing in both spoken and written forms. As such, language is a set of words and a system of rules for combining them (grammar and syntax), through which a community can communicate. The concept of the syntax of language might be extended to materials and organizational systems in music, and perhaps to communication and to meaning in music. To a lesser extent there is a language created by usage of the recording’s elements; recording’s language and its syntax of defining materials and building structure is in its beginning stages (Moore 2012a; Tagg 2013).

Syntax in Each Domain

The use of the term ‘syntax’ and its concepts in linguistics are adopted here to conceptually represent relationships and materials within each domain, especially those in music and in the recording. With this, ‘syntax’ creates a means to link all three domains in terms of basic-levels, structures, materials, and more.1 This allows insight into how the domains are contrasted and how they interact.

In the field of linguistics, the syntax of a language is generally agreed to be a set of rules, principles and processes governing the structure of sentences. Syntax dictates how words, clauses and phrases are combined into well-formed sentences, into sentences that conform to governing rules of structure in a language. In different terms, syntax provides the basis for coherent ordering of words (of various types) and phrases (with their different characteristics and functions) into properly constructed sentences, and how smaller units might combine into larger to result in fully formed sentences. From a finite set of rules for connecting words, an infinite number of sentences can be generated; each meaningful to one knowing the vocabulary and syntax of the language. Grammar, in contrast, dictates agreement between words and other aspects of the sentence, in how clauses and phrases communicate; syntax is a subset of grammar. It is common for people to be able to speak a language fluently with no formal knowledge of the language’s grammar.

These concepts of language and syntax are extended to organizational systems in music (Cogan and Escot, 1984), as well as related to meaning (Sloboda 2005; Tagg 2013). Syntax in music is generally agreed to refer to rules and conventions that shape musical materials and that guide its structure. Music has a syntax that is conceptually and (in some ways) functionally comparable to linguistic syntax in its hierarchical organization and complexity of variables—though, of course, containing its own substance.

Syntax of Music

Dominant theories of musical syntax are grounded in the principles and conventions of tonality; most particularly, the tonality reflected in the procedures of eighteenth-century European art music (reflected in its scale degrees, chord structures, key structure). Thus, traditional theories and related methods of evaluating musical syntax will have varying degrees of relevance (or irrelevance) to the analysis of the music of an individual popular song. The harmonic language of a song may well have little in common to the art music conventions.2 What might be considered a ‘universal law’ in the syntax of a formal language (or perhaps in any established musical tradition such as any European art music of an era predating the twentieth century) (Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1983) is in popular music a convention or a matter of musical practice slowly resulting in loose guiding principles. Conventions are established as musical practices are repeated and refined, though conventions are inherently a matter of artistic choice to conform to a common set of sonic qualities and principles of organization; conventions are invented constructions, not an inherent and universal ‘law’ of organization. A tremendous variety of music and production qualities is found in the tracks of today, coupled with all those stretching back to the beginning of recorded songs. There are few (if any) governing rules or principles outside individual genres (although the ‘words’ of music’s language may be borrowed or adopted across genres), and I venture to offer there is very little universal across them all. In reality, while (as with language) some syntax must be intact for music to be coherent, it is not rare for popular music artists to seek to ignore or wilfully counter anything that could be recognized as a ‘rule.’3 Think of how quickly one might recognize that a new track is by a known artist simply by recognizing telling qualities of the ‘sound’ of the track, or by language of the opening bars of the music, and when the text enters, if the syntax of the lyrics is not telling, the vocal timbre removes all doubt.

The ethereal language of musical style in popular music, the evolving language of the artist, and the language of the individual song are all in play in the syntax of a popular song. Examining syntax, it should be possible for every song to be recognized as unique in its materials, syntax and language of musical elements. Similarly, artists develop unique inclinations leading to a personal syntax within the language of the style. In some styles more than others, the individual piece of music may be based on a language or syntax that is uniquely its own (Zbikowski 2002, 138).

Just as with verbal language, we do not need to know explicit rules of grammar to understand music—or to perform music, or compose music. Music makes sense to us as we recognize its construction and materials—even if that recognition is not conscious (or non-discursive or nonverbal) and calculating of the matter and materials of construction (syntax and language) (White 1994, 55). At some inherent level, music communicates to a listener who is at least somewhat acquainted with its syntax. What it communicates to the listener, though, can vary—as how it makes sense can be individual, and what sense it makes might be immensely personal. As a musical style’s principles and conventions are known across a social group, the music communicates more broadly, and is understood similarly throughout a community and between its individuals. John Sloboda (2005, 179) offers: “It seems the mere exposure to the standard musical culture is enough for children to build grammatical structures.”

Syntax of Recording

There is an emerging language represented in the structure, content and usage of the recording’s elements; not surprisingly its depth and sophistication is much looser and simpler than what appears in lyrics and music. The typology and organization of recording’s elements establish its relationships of structure and its character. These can be conceptualized as syntax, and what is perceived as the recording’s sound qualities and their evolving appearances is generated by production style. Because recording is a young language (or languages if separately considering stereo, surround, VR, mono, etc.), its syntax is not as thoroughly developed, and its activities are largely static for extended time periods and are rarely temporal at the level of surface rhythms.

Listeners have few production-related expectations of sound qualities of recordings, although some generalized practices and conventions have become established that create an expected sense of relationships (such as the lead vocal located in stereo’s center). Recording’s syntax provides little sense of directed motion and of what should logically follow next, however—the grammar and syntax of succession that creates the tensions, expectations and resolutions of directed motion are latent, and remain in a process of being defined and established. One such example, though is the shifting presence of the lead vocal that often occurs in an established pattern of qualities between verses and choruses. The elements of recordings are still understood by the listener on a nonverbal level, however; the elements ‘make sense’ and function in ways that are recognized and processed by the listener, even in the absence of grammar in the language of recordings.

Still there is the basis of language and syntax. The attributes of elements shift through various values, and create patterns over periods time in their own ways (from microrhythms through macrorhythms); they form simultaneous groupings of attributes with and between other sound sources, establish relationships within elements. Further, recording’s elements substantially determine the character of the track’s overall sound. These all are leading to conventions of usage for consistently producing sonic qualities and relationships resulting in shape and motion within an element, but in ways vastly different from the elements of music or of lyrics. These have brought stylized production principles within genres of music—principles that might be explored through examining typologies.

Approaching elements by typology can provide some access to their content and activities. The approach to typology adopted here blends aspects of type 1 categorization and prototype effects explained by Lawrence Zbikowski (2002, 36–49), with principles of various computer programming techniques for data collection and analysis, and the concepts of a spectra of characteristics and contrasts of musical elements and materials employed by LaRue (2011).

Typology of recording’s elements can follow some of the identifying principles as music’s elements— though they are all unique in content.

Typology (as used here) is a flexible process of categorization, a way to organize data and make available pertinent examination of its content. The unique qualities of recording’s elements can be reflected in a typology that is set up to categorize its unique attributes and values. A typology might collect the following information (these are examples, not an exhaustive listing):

- Collection of identifiable attributes (or variables) and their values (levels, etc.), activities, states, or qualities within each element

- Spectrum or inventory of all values (levels, characteristics, etc.) within an attribute

- Range of values, levels or qualities within each attribute (such as the highest and lowest level)

- Increments between the values assembled in the 'spectrum of values' to identify the smallest and largest increments in use, and, if present, the lowest common value (this might be conceived as synonymous with the half-step in pitch as its smallest increment)

- Preferred or predominant values of each attribute or element

- Relationships of values between successive sounds, and/or between other sound sources that are simultaneously present

- Speed (tempo) of change of values (levels or qualities)

- Amount of change of values

- Static attributes (unchanging characteristics)

- Patterns of activity in and/or patterns of characteristics throughout events

- Any number of other attributes might most appropriately serve the goals of the analysis

Typology establishes the lexicon of the individual qualities within elements, and perhaps their organization. This set of data is (to extend the association with syntax) the alphabet and a budding vocabulary of the elements of recording. This will be of great use as we later evaluate the content and characteristics of the track.

Any element might generate materials that can create larger ideas by combining smaller ideas, resulting in more complete artistic statements, or in sound objects; and materials might likewise be divided into similar divisions. In this way the structure of linguistics’ syntax tree can be conceived as branches of structural relationships, and is context dependent—such an example would be space within space (see Chapter 8). With this approach it can be evident that the syntax of recording is both functionally and conceptually present, and will be approached as such in our explorations of the recording’s materials and organization.

To summarize this section, the concept of ‘syntax’ has been adopted in order to observe how ‘the language’ of each domain functions uniquely and to identify any similarity. It serves as a tool through which each element of each domain might be observed and evaluated, compared and synthesized with others. Thus far discussion has focused on the individual domains, and on the unique language and content of each.

Ultimately we engage the confluence of the three domains as the single overall sound—a multidimensional texture. Continuing the association with language and syntax, with this overall sound a ‘dialect’ of the record is formed. The dialect results from the three domains of the record communicating with a single voice. The unique qualities of individual tracks are reflected in this syntax of confluence, as well as in the ways its materials are constructed (typology) and the ways they are organized (structure) within the individual streams of each domain. Through examining syntax, the unique qualities of the individual record will begin to emerge.

FUNCTIONS AND MATERIALS OF DOMAINS AND THEIR ELEMENTS

The multidimensional texture created by the confluence of the three domains can seem a kaleidoscopic array of activity. Elements within all three domains contribute to the song in any number of unique ways, at every moment in time. In doing so, the domains and their elements acquire function within the materials they shape; they come together in various ways to create vocal lines, instrumental parts, accompaniments, and much more.

Elements contribute to and present the musical, lyric and recording materials and ideas that are infused with the expression of the song. Each element is in a defined role; each at a certain level of significance. Domains, their elements and the materials of the song they establish all function in various ways within the song, and often change roles as the track unfolds.

Elements can play a primary, supportive, ornamental or contextual role (function) in shaping materials. For instance, traditional approaches to analysis will identify the melody of a lead vocal as being comprised of pitch and rhythm, and perhaps harmonic implications of the line. There are many other elements that appear as well; each is of concern to us. A few might appear as a slowly changing vocal timbre shaping performance intensity of the line, dynamic shaping of individual notes and/or of the entire line, unique alignments of pitches and vibrato against the metric grid, subtle expansion of the phantom image, distance placement, and more. These elements all have a role in shaping the line, some primary, others in another role (but all sharing an equal potential to function at any other level of significance), as they coalesce into a single idea or material.

The materials of the recorded song and the sources that perform them also assume one of these same four functions, though in their own way. Table 2.5 outlines a potential hierarchy of performers/ instrumentation and their materials based on function in a hypothetical song. The table identifies the significance of each part based on function. The dominant element(s) that shape those parts follow. The table represents typical parts and instrumentation of a track, but does not represent a model; an

| Primary Materials & Elements | Supportive Materials & Elements | Ornamental Materials & Elements | Contextual Materials & Elements |

| Lead vocal - song's persona; delivery of text; melody/pitch, lyrics/sound quality, rhythm | Rhythm guitar - harmonic accompaniment- harmony, rhythm, sound quality | Backing vocals - verse ornamentation; sustained harmonies, sound quality, register | Drum set - groove, pulse; rhythm, pitch registers, sound quality |

| Lead guitar - melody/pitch counter melody, solo section; chord progression theme | Piano - harmonic accompaniment; harmony, melody, sound quality | Ancillary percussion strikes - rhythmic reinforcement; rhythm, sound quality | Bass - groove, pulse; melody/pitch, register, rhythm, implied harmony |

appropriate reduction of possible collections and relationships of parts and materials will emerge from the track itself to illuminate an analysis.

Functions

The four fundamental functions are primary, supportive, ornamental and contextual functions. These functions are roles, elements and materials (musical, text or recording materials) that, respectively, serve to deliver primary ideas, support or reinforce the primary material, embellish material, or create a sonic context or backdrop.

Elements, domains or materials that carry the weight of content and expression are substantive; they present the central ideas of the song represent the primary function. Examples of these in the music domain might be the ‘material’ of main melodies of the song—typically the lead vocal line is shaped primarily by the musical element of ‘pitch,’ of course. The primary materials might also include other musical elements: a dominating beat, groove or a recurring rhythmic pattern occurring within the element of ‘rhythm,’ or a ‘striking chord progression’;4 elements of the text can typically be primary elements as well, or elements of the record might serve a primary function. Parts with primary functions are essential to the song, and deliver its core themes and ideas, character and characteristics.

Materials, elements and domains in a supportive role provide reinforcement to those in a primary role. In providing reinforcement, they add critical dimension(s) to the core character and are also essential to the fundamental qualities and nature of the record. They add character to the primary materials and support that material in contributing to fundamental shape and motion.

Elements (or groups of elements) that dominate primary materials of a track (or a specific section or structural level) are controlling elements. Controlling elements are those elements that contribute most significantly to structural organization and/or to the over-riding motion of the track. Controlling elements drive movement and/or are the most substantive contributors to shaping the primary materials and concepts of the track.

Those elements with an ornamental function provide enhancement to the essential—whether supportive or primary. An ornamental element adds character by providing decoration to the essential qualities of materials. Materials/elements in an ornamental role embellish the substance found in others; they are not essential to the track’s core, but provide important nuance and adornment. Ornamental treatments are often important characteristics of musical style and performance technique.

Elements or materials with contextual functions establish a sonic context or backdrop that is more or less consistent throughout the entire track or major sections. They might present an ambience or some specific dimension to an overall sound, against which all other materials and all other functions play out. Contextual functions are inherently stable, and create a unifying aspect to the track.

In typical recorded songs, primary materials are dominated by the elements: melody and pitch relationships. The supportive roles might be comprised of rhythmic activity and pitch relationships providing harmony, and some parts emphasizing sound quality; ornamental roles might be assumed by dynamics and the timbre changes of interpretation; contextual roles might be reflected in the sound stage dimensions or perceived performance environment, and others. Obviously, these examples are highly simplified, incomplete and are not universal. The track is much more complex.

Recognizing this concept of interrelationships of elements and functions applies to each domain and between domains, a myriad of possible combinations results. This vast number of potential interactions point to the complexities within even the simplest of records—and the number of potential ways a song might be shaped. These many interrelationships shape and create its many dimensions and structural levels—this stratification is explored below.

Domains also assume these roles of function—at a higher dimension. Any domain can serve the primary function for the entire song, or might switch to a supporting or an ornamental role. Using text as an example, that domain might provide the controlling elements and primary materials throughout much of the song, and assume a secondary role when only backing vocals delivering only vowel sounds are present during a certain section. Switching of roles for domains is typically apparent between sections, but might occur at any moment in the record.

Still, in recorded song, the lead vocal nearly always plays the central role, and assumes a primary function. This is perhaps the only universal rule or principle of recorded song.

The conventions5 that establish any musical style bring certain relationships of elements (creating stylized musical materials) and their functions to dominate, or be most common. Conventions may also be reflected in typologies and characteristics of the materials. Individual songs in any musical style will deviate from convention at least somewhat in order to provide novelty, interest or variety, though certain intrinsic relationships of materials and elements will remain evident.

In all types of song, along with the lead vocal (with its musical elements and its text) any of the elements of music might be ornamental, supportive or primary at any moment, or throughout a major section of the song; any element or group of elements may be its controlling element. Similarly, any of the elements of the domain of the record hold equal potential to assume any function in shaping the materials of the track, and in relation to the musical elements, or to the text. All elements of all three domains share the potential to be equally significant (or provide context, support or ornamentation) in shaping and providing content for the song.

This concept of equivalence is the recognition that each element has an equal potential to assume any function at any moment in time—no matter its domain. Any element has the potential to be the central carrier of the artistic statement at any moment in time; any element may also be in any other role, and that function might shift at any moment (Tenney 1986). This is a guiding principle in listening as well as in analysis.

This discussion of functions of elements and of formulations of conventions in the record brings a way to access and recognize the contributions and qualities of the recording’s elements, typologies and concepts.

Inside the Elements and the Materials of the Song

Reviewing Table 2.5, common allocations of materials are apparent. Some individual parts/lines are performed by a group of instruments, and others are performed by a group of voices; many materials are presented by a single instrument or voice, while some instruments may present several musical ideas simultaneously (common in piano parts). Each of the musical materials may be defined by a number of elements that are actively shaping or otherwise significant to those materials. Identifying the activities and functions of the elements that shape and characterize the musical materials is a central concern in recording analysis.

By considering George Harrison’s lead vocal in the first verse of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” (LOVE stereo version, 2006), we might recognize some of the contributions of elements to the track’s materials.

From the entry of the vocal we readily identify a single line of pitches, organized by rhythmic patterns and patterns of intervals, delivering a text exhibiting a variety of sound qualities and rhythmic elements, and performed with dynamic shaping of the melodic line and precisely placed vocal timbral qualities. This statement is purposefully vague to illustrate it could apply to any vocal line, and that it is without distinguishing detail—it does not allow us to learn about the line. To bring clarity to the content of the vocal part we might examine (as appropriate): (1) the melodic structure and pitch content of the vocal line, and its phrasing, (2) implied harmony and other patterns of intervals, and repeated phrases or repetitions of partial phrases, (3) the rhythmic and dynamic elements that further shape the phrases, (4) the text sounds and rhyme scheme, text rhythm and the repeated lines and words. This is only a start.

Upon further examination of these text and musical elements in Harrison’s vocal, we identify the significance of various pitch relationships within the context of the song; the placements and stresses of the rhythms related to the meter, phrasing, text structure; the timbral modifications of the text to bring expression and emphasis, and clarify meaning; the tessitura of the line, placement within the singers range; and more. There are intentional qualities to the recording, too; the proximity of the vocal, distance of the guitar, and the open areas of lateral space between Harrison’s vocals and the strings. The exposed nature of the vocal allows ready access to these observations, including intentional recording gestures.

With further listening, one becomes increasingly aware that the lead vocal is more than a melody of pitches, rhythm and words. It is the result of the performance, where pitches do not always conform to scales, and rhythms flex for expression or to more closely reflect speech inflection. Word timbres morph in quality without changing vowels, all the while communicating intensity, a certain level of tension and an expression of melancholy—and more.

Harrison’s first verse vocal is also shaped by the elements of the record. The vocal has a width of approximately 8-degrees and is centered in the stereo field; it is located within close proximity to the listener, and while there is just a short length of distance between Harrison’s voice and the perceived location of the listener, there is also some instability to distance cues generating some ambiguity and motion. The vocal’s dynamic level in the mix is markedly louder than the moderately soft intensity level at the performance’s beginning. Finally, there is a negligible influence of environment cues with only the environment’s barely noticeable accentuation of timbral characteristics within the vocal’s frequency range.

As these observations demonstrate, methods used to evaluate the lead vocal’s melody, harmony and rhythm are of no use to evaluating the record’s elements. Nor are they applicable directly to evaluating the lyrics. Elements from each domain are unique, and can be vastly different from one another. As we have just observed, the record’s elements are equally important to hear and understand as the music elements, or the content of the text. This gives rise to questions of concern on how the elements, materials and domains interact. A beginning might be:

- How does the music present the lyrics, enhance them, support them?

- How are the lyrics and the singer's voice quality utilized to present the musical ideas and materials?

- What does the recording contribute to the character of the music, of the lyrics, of the track?

FORM, STRUCTURE AND PERSPECTIVE

Within our human experiences of time and space, internal or external, we grasp to make sense of our perceptions—of all kinds. The record is no exception. As we experience materials and their component elements, they coalesce into shapes and events, into sequences and patterns, into hierarchies and structure, into concepts and form.

Recorded songs have form, in three types. First, form is an overall shape comprised of recurring large sections, defined by their materials (Cook 1987). Second, form might be framed as a global quality, whereby the record crystallizes into a singular core essence (Moylan 2015). Third, form can be conceived to reformulate the recorded song from a temporal experience to a realization, or conceptualization of out of time (Tagg 2013).

Herein ‘form’ and ‘structure’ are defined and used as separate entities and concepts. While many sources and common convention might use them synonymously, a distinction is made here so these terms might bring some clarity to important opposing, but complementary ideas.

In this approach, form is the record’s shape, frozen in time. It is the recorded song crystallized into a single sound object, one unified and multidimensional entity or conception. Form does not evolve as an event; it is a memory of the song fully formed, as an object of many dimensions. Crystallized form, like sound object, embraces the notion of music as a memory, crystallized into a single representation of overall qualities comprised of rich detail and existing out of time. Crystallized form is distinct from the concept of sound object (Schaeffer 1966), however; a sound object is isolated from the context of the track, whereas crystallized form is the context of the track.

This contrasts with structure. Structure provides hierarchies and the relationships that bring form to its overall shape. The recorded song’s structure is the architecture of its materials. As such, structure is comprised of many component parts that represent the materials of the song, at various levels of scale and significance. These materials establish interrelationships as the track progresses throughout its duration; its many section, phrase, sub-phrase and combination of section time-spans establish a complex hierarchy and stratification of structure—and the materials of the recording are also present within the structure, as are those of the lyrics.

Structure is dynamic and continually unfolding. Its materials are sound events. Events begin, progress and conclude; they appear experientially while unfolding over time. Structure recognizes motion and movement, departure and arrival, tension and resolution. The sound event draws attention to the experience of the existence of sound and music over time, as unfolding structure.

Table 2.6 Defining and contrasting concepts of form versus structure.

Structure encompasses the characteristics of all materials (and all elements that shape them) coupled with a hierarchy of their interrelationships, as they function and provide motion. The structure of the music will be the basis for examining the structure of the track; in other words, the song’s structure will be used as the reference against which the structures of the three domains are related to one another. The elements of all domains function to provide the musical materials with their unique character. All musical materials, their functions, content, and time-spans can be related within the hierarchies of structure.6

Time Perception and Pattern Perception

Two areas of perception are central to experiencing the track and its structure and form: time perception and pattern perception. These also impact the perception of all temporal aspects of the record, its domains and its elements.

We might understand the track more deeply by examining time perception and how our perception of the passage of time differs markedly with and without engaging the metric grid. Recognizing our innate and our learned organizational abilities for pattern perception, will provide some clarity when engaging groupings of materials of all elements and dimensions. The motion and dramatic effects of rhythm and its organizational force will become clearer as examination of each element unfolds.

Time perception not only factors into the perception of rhythm, it also factors into the perception of time units for evaluating subtle qualities of environmental characteristics and timbre. It is also central to the listening process and in recognizing the global qualities of form. The following discussion is applied in observing all elements, refining listening skills and in conceptualizing the track.

Time perception is distinctly different from duration perception. We make judgments of elapsed time based on the perceived length of the present. The length of time humans perceive to be “the present” is normally two to three seconds, but might be extended to as much as five seconds and beyond. We do not perceive the passage of time as such, but rather what we do perceive, we perceive as the window of time of our existence, the present time—as what is going on right now. This ‘right now’ is a window of time within which occurrences are perceived as occurring during the moments of active, conscious awareness; the tipping point between the past and the future within which our lives play out. The present has “fuzzy edges” (Snyder 2000, 51) that are limited by the type, speed and amount of information that occur within short-term memory (STM)—averaging 3–5 seconds, and may reach as long as 10–12 seconds.

From this we recognize, while we are hearing in the present, we are hearing and understanding as a function of memory. This front edge also contains the briefest of the three memory types, echoic memory; its duration is maybe 2 to 3 seconds and it functions for perceptual processing of various sensory memory systems (Zbikowski 2011, 185). The maximum length of the experience of hypermeter seems to be influenced by the amount of information (lengths of measures, number of measures, amount of stimuli within measures) that can be held in STM (Kramer 1988, 372). Working memory is a buffer of around 10–15 seconds duration “within which information provided by perceptual processing can be evaluated” (Zbikowski 2011, 185); it is important for many processes, one ready example being the processing of language, which requires holding an amount of information, evaluating it and then determining its content and what to do with it.

This is the psychological present; it is our window of consciousness. It allows conscious awareness with which we perceive the world and listen to sound. We are at once experiencing the moment of our existence, evaluating the immediate past of what has just happened and anticipating the future (projecting what will follow the present moment, given our experiences of the recently passed moments, and our knowledge of previous, similar events).

Humans do not perceive the passage of clock time accurately; judgments of clock time are inherently imprecise. The time length of a piece of music (or any temporal art form, such as a motion picture) and all temporal aspects within the metric contexts of the record are separate and distinct from clock time. A lifetime can pass in a moment, through the experience of a work of art, and its aesthetic and dramatic statements. A brief moment of sound might elevate the listener to extend the experience to an infinite span of existence. Just how the experience shapes time perception is complex, and is not consistent between listening sessions to the same work, let alone between individuals. Time judgments are strongly influenced by the listener’s attentiveness and interest. If the material is stimulating, the event might appear shorter in duration; desirable experiences typically seem to occupy less time than would an undesirable experience of the same (or even shorter) length. Expectations, interest, contemplation, mood, energy and even pleasure caused by music can alter the listener’s sense of elapsed time.

Within musical contexts, humans have the potential to accurately gauge clock time. The metric grid can be used to calculate clock time. The process is to recognize a tempo meaningful to the listener, and to transform that tempo into a metric pulse; the pulse may then be transposed into a tempo of a pulse per second or half second. This will obviously work more effectively for some tempos than others. With this sense of recognizing clock time, time units can be recognized, allowing observations of timbre and spatial dimensions to be practical. Time units as short as a few milliseconds will become recognized as timbres of time, containing unique sound qualities; this allows access into identifying and understanding several important dimensions of recordings. This skill will also be useful in hearing the nuance of subtle rhythmic fluctuations of performances, and will assist in defining the characteristics of materials; praxis studies for developing an awareness of small increments of duration as timbre-related percepts and as related to clock-time are contained in Appendix A.

Listening to records is facilitated with an awareness of the window of the present. This is an understanding that what is being heard ‘now’ will soon be past, and will be replaced. It sets intention, heightens and cultivates attention and focus.

An event occurring over time might be perceived as an aural image, its qualities simultaneous instead of sequential. The temporal aspects of perception are suspended and awareness shifts to the global qualities of a piece of a recorded song, and toward appreciating the broad and textured shape of form as ‘stilled time.’ The entirety of the record is thus represented as auditory image (not unlike a visual image), where information on the work has coalesced within long-term memory into a single object; such a perceptual representation is not time-dependent and is pre-verbal.7 Our creating auditory images of music might explain why many aspects of music’s meaning and expression defy verbal explanation (Snyder 2000, 23). The qualities of crystallized form appear largely dependent on suspending the temporal experience of music—and broadening the perception of the passage of musical materials across the listener’s focus of conscious awareness. In effect, this allows the listener access to the entirety of the piece of music within the elongated window of the present.

Pattern perception is a deeply ingrained cognitive process; it is central to how we perceive our complex environment. We use pattern perception to process the complex information that arrives through sight as well as sound. At its most basic, structure (and the activities of all elements, especially as related to rhythm) is comprised of patterns of activities and their durations—durations that are organized into patterns within perception (Sloboda 2005). Pattern perception carries to pitch, where melody and harmony are understood by their patterns of pitches; patterns can be established in all other elements, as well.

These patterns are deciphered from the mass of sound (the acoustic wave) arriving at each ear through groupings of acoustic events “formed by their basic similarity and proximity to each other” (Snyder 2000, 264), and “the tendency for individual elements in perception to seem related and to bond into units” (ibid., 259).8 Here we interpret ‘elements’ to refer to activities occurring within each element of the track, bonding into an event (such as a musical idea or a language statement). Grouping may be innate (happening automatically) or learned (requiring the engagement of long-term memory), and thus can conform to changing contexts—individual records (Sloboda 2005, 135–146). Grouping can occur at multiple levels, and results in the breaking of the acoustic wave into separate events (typically any number of simultaneous events) (Handel 1993, 185). This is stream segregation that brings the perception of individual temporal ideas (including language and music), where each event becomes a separate stream—even if overlaying or overlapping. Streams may be sound sources, musical lines and materials, lyrics, performances, recording’s gestures—anything that can be identified as a separate event. This is relevant for us because each event stream unfolds in time, and has its own iterations, its own rhythmic patterns, its own structural relationship with other streams and to the whole.

These rhythmic patterns are created differently within each individual element in each domain, and (as we have already encountered) the elements in play all fuse to formulate the track’s materials and also multi-dimensions in elements of music such as melody and harmony. The ways patterns are established within individual elements will be examined as each is presented.

Hierarchies and Structure

Within the hierarchy of structure, the song branches out into structural layers and sections of time units. These time divisions are reflected in the sections of the song, and used as a reference herein; larger sections may be verses or choruses, groups of verse-chorus combinations; smaller sections are compound phrases within song-sections (such as verse or chorus), phrases within song-sections, sub-phrases, beat patterns, and so forth. In this way, every musical material is a subpart of other, higher-order order musical materials; all time spans of beats, measures, phrases, etc., are imbedded within other higher-order sections.

Further, this hierarchy of the musical structure organizes musical materials into patterns and patterns of patterns; contrasting and complementary materials; repetitions and variations; etc. In this way, relationships are established between the subparts of a work and the work as a whole. The hierarchy is such that any time span may contain any number of strata of smaller time-spans, and may be contained within any number of strata of larger time spans; musical material at any level may be related to material at any other structural level. This musical structure can serve as the basis for organizing the materials and elements of the recording, and a template upon which the structure of the lyrics can be displayed.

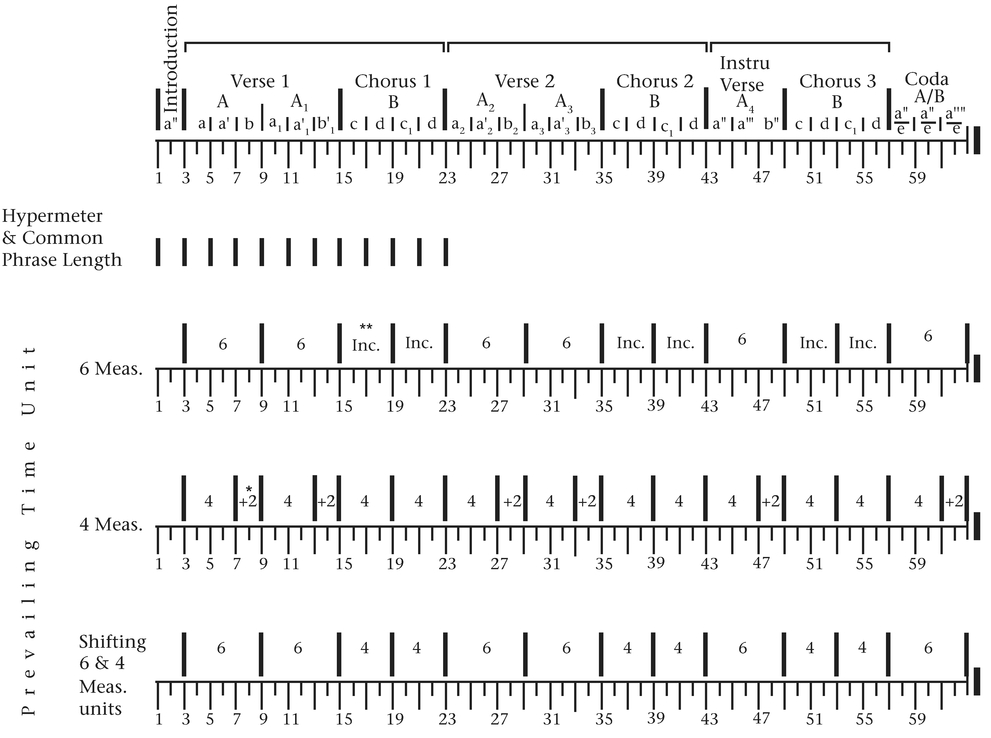

Figure 2.1 presents the structural hierarchy of the Beatles’ “Every Little Thing” (1964). This diagram allows us to recognize the common phrase length between all sections is 2 measures in duration, and the patterns created by these phrase-level materials. In this example, phrases are labelled using lower case letters; numbers following the letter denote changing lyrics, tick marks denote changes in musical materials. Compound phrases within song sections are upper case letters, and song sections are named. Groupings of song sections are bracketed, allowing quick recognition of the verse-plus-chorus groupings that reside at a higher structural level than the sections.9

These temporal divisions represent passage of time. The materials within the divisions chronicle the flow of movement to the song—gauged against the underlying pulse of the metric grid. This allows observation of processes that draw music through time. Movement is created by directed motion of tension pushing or leaning toward resolution, temporary relaxation of arrival points, cycling oscillations of activity that provide minimal forward momentum, and more. Created by musical materials, their interactions, and stylistic tendencies, movement delivers the moment-to-moment experience of structural materials and relationships unfolding. Movement’s journey through time—embodied in a myriad of speeds, amounts and intensities of motion from the slightest, most restrained crawl of complacency to the immense, most extreme burst of urgency—is propelled by any of the elements of the record, the intensities of the performance, the drama and unfolding story of the lyrics, scene changes between invented worlds in the recording, and all that is the record.

*Extention of Unit (floater) **Incomplete Unit Figure 2.1 Structural hierarchy and overall shape (form) of “Every Little Thing” by the Beatles.

Within this sense of motion and rhythm of time passage, there exists an underlying dominant section length. Each song will have this time module of activity—a phrase-length or section length that establishes a fundamental characteristic of the song. This phrasing drives or propels the song along with a regularity of pacing; it forms a steady, cycling, pulsating wave of forward motion. This is the ‘prevailing time unit’ (PTU). It resides in the middle dimension of the song—its length is typically aligned with the ‘basic-level material’ (explained below) or a multiple of that length.10 It is the hypermetric grouping that organizes the passage of materials into a fundamental recurring structural division. This is a syncrisis unit—manifesting here as a perception of a coherent temporal grouping with a duration that repeats incessantly—as will be discussed below.

Thus, the prevailing time unit is a length of metric time that repeats throughout the song. It establishes an underlying, regular wave of time—a consistent pulsation—within the structure. It is a regular rhythm of groups of measures or beats (other than a single metric bar) that form a dominant, reference time unit within the structure. It establishes a section-length reference for the song, whereby all time units and other aspects of the song can be related. This phrase length that is the PTU is evident; it is a strong organizational factor that is felt as well as heard in the regular succession of materials; its length is not subjective and is just as evident as is the metric grid. 11

The prevailing time unit may be momentarily interrupted—extended or contracted, and several iterations of the PTU may even overlap—but it is always present. This temporal distortion of the regular time flow of the song is felt as a shift and/or a disruption, and its impacts are often temporary. Primary musical materials will directly align with the PTU in some way, as will the basic-level materials of the other domains. The PTU functions as a reference time length whereby we calculate or recognize (often subliminally) changes and points of arrival within the structure, and the significant materials.

Examples of tracks with a clearly apparent and consistent prevailing time unit are many. They are by far the most common in popular song. Figures 5.3 and 9.4 outlines the structure of “Let It Be” (in various versions); the track’s PTU of four measures grounds each version and does not waiver in the context of pacing it provides. The shifting groove of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” (1968) underlies the song’s driving and incessant PTU of eight measures (Figure 5.1); continually pushing forward, the regularity of this eight-measure prevailing time unit persists even through the fade of the coda, with its last sounds absorbed into silence during the eighth measure of the final PTU.

Still, every recorded song is unique; the regular, structural ebb and flow of the PTU is also subject to appearing in a unique manner. For example, the prevailing time unit in “Every Little Thing” is more ambiguous than most popular songs. One is inclined to interpret it in a number of ways. These are illustrated in Figure 2.1; there the two-measure common phrase length is identified as well as major (song-section) structural divisions, and the verse-plus-chorus groupings that establish a higher order strata of the song’s structure. The potential PTU lengths that emerge are:

- Four (4)-measure PTU, with two-measure extensions in each major phrase within the verses; the PTU then is unaltered in each chorus appearance

- Six (6)-measure PTU with interrupted or incomplete units in the choruses; the PTU is unaltered in each verse

- Shifting of the PTU between verses and chorus appearances

A four-measure PTU is clear within each chorus appearance. Applying the four-measure PTU throughout the song requires a division of each six-measure phrase of the verses, bringing the PTU to be heard as extended by a two-measure phrase that completes the ‘aab’ sequence; the verse divisions are structurally organized and are propelled by movement of three two-measure phrases that form a 4+2 grouping. Walter Everett (2009a, 187) identifies this structural concept as an “expanded prototype” and calls this added two-measure phrase a “floater”; a floater is usually two measures in length and is attached to the front or back end of a four-measure phrase. The “floater” extends the four-measure phrase to six-measures; this would temporarily disrupt or shift the PTU.

A six-measure PTU might also be considered, as that is the length of the defining grouping of each half of each verse (each ‘aab’ sequence). This requires each half of choruses to be heard as being an incomplete presentation of the PTU, or heard as one that has been interrupted; neither of these fit the material, as the phrases are complete, coherent materials with their own structure and movement. While a six-measure PTU tends to be reinforced by the solo and the coda, the chorus appearances do not have structural or movement characteristics of being contractions or interruptions of six measures. The chorus is stable as it appears, and so is the verse. While the two measure phrase length is common between both sections, it does not reflect the musical movement of either the verse or the chorus— where materials clearly articulate closure at the end of either four- or six-measure phrases.

While a shifting prevailing time unit counters the definition of an underlying, consistent wave of time throughout the work, some works exploit ways to interrupt, shift, expand, contract, or bring ambiguity to it. Songs like “Every Little Thing” are the exceptions that confirm convention by offering contrast. The verses are clearly 6+6, and the choruses 4+4. The PTU might be interpreted as shifting between verses and chorus; a changing span of syncrisis. This contrast is not typical, but not uncommon. The Beatles used wide ranging surface rhythms, asymmetrical meters in songs such as “Within You Without You” (1967), and many examples of freely mixed meter as in the repeated 4/4 and 3/4 alternation in “All You Need is Love” (1967). Their creative use of phrase rhythm brings larger-scale patterning generating hypermeter and PTU that can exhibit instability, but also movement (notice the PTU shift in the middle section of “Here Comes the Sun” in Figure 9.2). Walter Everett (2009a) explores the Beatles’ free phrase rhythms in considerable depth, identifying six characteristics of these irregularities that impact PTU. The Beatles used what might be heard as a shifting prevailing time unit numerous times, and perhaps more than other songwriters. A shifting PTU of contrasting lengths is clearly present in “You Never Give Me Your Money” (1969) and “We Can Work It Out” (1965). The shifting meters between and within sections of “She Said She Said” (1966) and “Here Comes the Sun” (1969) bring PTU and hypermeter adjustments as well. Metric modulations between sections in “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (1967) (illustrated in Figure 9.3) and transitioning into the final phrase of “The End” (1969) provide coherence to changing tempo, meter and PTU; the result is a shifting of the prevailing length (both metric and clock time) of the unit that depicts the time span of movement as well as surface rhythm.

Dimensions of Structure

The hierarchy of structural divisions can be grouped into three basic dimensions: large, middle, and small (Moylan 2015). These allow the examination of structure and musical materials at clearly defined levels of detail, and allow levels to be compared in many ways. All strata (levels) of structural hierarchy are contained in one of these three dimensions—dimensions that are sometimes conceived as micro-, middle- and macro-levels in music analysis (White 1994, 24–27). 12 Note, these three dimensions have no relationship to the Schenkerian analysis concepts of foreground, middleground and background.13

Large dimension concepts concern the entire song. Should one be examining an entire album, this large dimension might be a group of songs or the entire album. Large dimension may also be considered as the uppermost level and highest, simplest grouping(s) of major sections/time-spans of the song. Large dimension relates to language at the level of the entire work (poem, story, book), or major divisions such as the parts of a book that group chapters into a few key subjects (roughly the equivalent to the movements of a symphony).

Small dimension recognizes the smallest ideas and relationships. Small dimension materials are related to sub-phrases, melodic motives, rhythmic cells, riffs, beats, timbres of individual sounds, and so forth; in some songs shorter phrase lengths may be small dimension. The smallest, subtlest details of musical materials and performance, of music elements, the elements of the record, or the text’s elements are represented in the small dimension. Much detail will be discovered here. The small dimension detail functions to embellish or combine its groupings to create middle dimension materials.

The small dimension relates to language at the level of words and syllables, where complete ideas are not formed. The middle dimension is related to language—structural levels of clauses, phrases, sentences, paragraphs, sections, and chapters. The middle dimension is the most varied and complex of the three dimensions.

The multi-layered middle dimension holds the majority of the information and activity of the song. It is comprised of strata of mid-level activity, and is where the primary ideas and concepts of the track are present and evolve. The majority of individualizing characteristics of a song and its characteristic materials and internal workings are resident in this dimension. Songs differ in complexity, and many individual levels can exist between the small and large dimensions, or there may be just a few, depending on the individual song.

In this stratified middle dimension, we find some references by which we calculate workings of the song, as materials and elements carve out and establish their places. The prevailing time unit will exist somewhere within the middle dimension; this precise level of where the PTU is present is the ‘characteristic dimension’ of the recorded song. This is the level of dimension that inherently reflects the motion of the song, and which serves as a structural reference against which other levels of the structural hierarchy are gauged.

As mentioned above, the primary musical materials of the song directly align with the PTU in some way, as will the materials of the other domains. These all are resident in the middle dimension at the level related to the idea of the ‘basic-level’ of categorizing materials. ‘Basic-level’ is a mid-level perception/cognition that is central to categorization and to our structural grouping. It also pertains to delineation of sound sources and their materials; in future discussions we will observe how the basic-level is the perspective at which humans interact, and sound sources (performers) exist as the categorization of reference. Discussing the categorization of objects, Lawrence Zbikowski (2002, 33) explains:

These basic-level shapes reside in the middle dimension, and represent individual concepts within a larger context (middle dimension within the large). It is in the middle of the dimension, the most useful for categorization and also clearly presents the central, primary materials and concepts of the song— these materials are complete (rather than parts of whole thoughts, statements, ideas), and are perceived by shape as much as content. Therefore, in this one specific level of the middle dimension we find the primary musical ideas, the primary statements and concepts of the lyrics, and the central characteristics and relationships of the recording—a level that provides a critical reference to the song.14

Perspective

This division of structure into three dimensions is related here to perspective. Perspective is one of the guiding principles of the analysis framework.

Perspective is the act of perceiving at a specific level of detail, as if from a defined vantage point of observation. Eric Clarke (2005, 188) has called this the “scale of focus” of attention, “one of the remarkable characteristics of our perceptual systems, and the adaptability of human consciousness, is to change the focus . . . of attention.” 15 This may be applied to listening at any level of the structural hierarchy—attention focused, observing materials/elements functioning or appearing at the same level of structural activity. Perspective allows the recorded song to be observed from various but specific levels of detail, and with attention directed to musical materials, specific elements, any groupings of activities within that structural level, etc. Clear use of perspective relies on the listener’s ability to bring focus of attention to specific materials at specific levels of detail.

Each level of detail represents a unique perspective from which the material can be heard, and the song examined. Perspective allows the listener to observe different qualities, content and activities of the sound material and its elements. At times it is helpful for perspective to be considered as a conceptual distance between the listener and the sound material; the nearer the listener to the material, the more detail the listener is able to perceive. Simply, perspective is the level of detail at which one is listening; focus brings the listener’s attention to a specific level of perspective. (Moylan 2015, 92–95, 112)

Critical to utilizing perspective is the ability to consider elements/materials in relation to one another clearly and accurately. Elements/materials are compared at the same level of detail in the structural hierarchy; there each has equal opportunity to assume any level of significance; further, any element might have a different function in any dimension, or level of perspective, simultaneously.

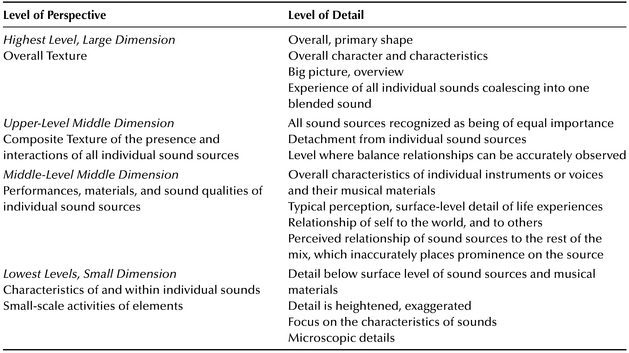

Levels of perspective and related levels of detail for the recording are outlined in Table 2.7. Observing this table, we might identify the overall qualities and shapes created by the recording’s elements and materials. On the other extreme will be the subtle details of individual sounds, materials, elements, etc., that take place below the surface; such information demands heightened attention to detail within sounds. As in discussion of middle-dimension structure, a significant amount of information and activity takes place in the middle dimension perspective. Two primary perspectives are central to understanding the recording, they are (1) the texture established through the interactions of all sound sources within an upper level of the middle dimension (this is the ‘composite texture’ where all sources appear as an equal presence), and (2) the level of the characteristics and activities of the individual sources. These similar but distinctly different perspectives allow the sound sources (instruments and voices) of the recording to be accurately perceived and accurately compared (Moylan 2017).

The structural hierarchies of the three domains might now be recognized as functioning in parallel. The strata of structural hierarchies function similarly within each domain; each domain functions according to its unique syntax, materials, elements and modes of expression. Structural levels can be compared across domains by observations at the correct perspective, from the lowest through the highest levels.

Table 2.7 Levels of perspective and related levels of detail.

While at the highest level of perspective each domain may be heard individually as an overall quality (as a fabric of its unique elements, character and characteristics), within the experience of the record the domains fuse. All blends into a single complex, multidimensional quality that is more than the sum of all of its parts—as elements complement, support, enrich and add meaning to other parts, across domains, across levels of perspective and structure. In an all-inclusive “weave of fabrics” (Erickson 1975, 139) the three domains create a multidimensional texture.

Arriving at this highest level of perspective and the upper stratum of structure, we encounter the traditional concept of form as shape.

Form: Shape and Stilled Time

Form is a term used here for three separate concepts:

- Traditional shape. Comprised of the succession of major sections.

- 'Now sound' of syncrisis. The intensional, synchronic sonority within the window of the extended present.

- Crystallized form. The mental representation of the work's essence, conceptualized as a single manifestation, heard simultaneously, crystallized out of time.

In its traditional usage, form is the shape created by the progression of the song’s major sections—the sections at the highest level of structure. Form is the memory of movement. The sections are labelled and arranged as they move in succession, in passing time, until the whole is represented. This approach to ‘form’ or ‘formal structure’ (structure at the highest, ‘form’ level) is still useful to illustrate the shape of the song as produced by structure. These highest order sections allow the ‘shape’ of the work (song) by the relationships of major sections to be recognized.

After acknowledging this traditional notion of musical form, Philip Tagg (2013, 385) has identified “aspects of form and signification bearing on the synchronic, intensional, arrangement of structural elements inside the extended present.” In this concept of form, which he calls syncrisis and ‘now sound,’ form is “created through the arrangement of simultaneously sounding strands of music into a synchronic whole inside the extended present.”16 The vertical aspect of musical expression (intensional) within the limits of the extended present (ibid., 591) is often called ‘texture,’ but there is further richness here. “Syncrisis involves the simultaneous combination of elements and can also be considered in terms of shape, form, size, and texture of a scene or situation” (ibid., 417) within the time perceived as ‘now’ extended to encompass the experience (incorporating aspects of short-term memory functions).

This provides a window for the immense complexity of the track to be observed with greater clarity. Further, the notion of the extended present related to musical materials allows the individual sound to be a ‘sound object,’ and is also important for recognizing musical structures (such as the prevailing time unit) and materials (such as ‘pitch density’) where sound activity over a period of time is linked, or for chunking (memory process identified in psychology) which binds the pieces into a meaningful whole, into a unit that can be recognized and remembered.

Syncrisis also acknowledges the ‘scene’ as a span of time (a window of the present) in which materials are grouped and shaped, ideas and drama play out; “a pop song . . . is more likely to [derive interest] in batches of ‘now sound’ in the extended present” of which the “3.6 seconds of guitar riff accompanied by bass and drumkit in Satisfaction (Rolling Stones, 1965) is a textbook example” (ibid., 272). Metaphorically the composite ‘now sound’ can be considered as a scene; as part of the whole song, with its own contained sound and message. It can also “connect with patterns of social interaction specific to the culture in which they are produced”; in this way

Within the track, syncrisis can manifest the prevailing time unit as a scene (or rather a consistent pulsation of scenes), can bring musical gestures to be coherent sound events or sound objects. Chunking helps moments to be linked into scenes of greater breadth, but with a singular impression; it brings us to experience syncrisis. For the analyst, syncrisis opens considerations of characteristics and qualities of different sorts—ones at different structural levels, different conceptualizations, and more.

The third concept of form—crystallized form—is central to the analysis framework. It is integral with shape, reconceived to acknowledge the piece of music can be perceived synchronously, all at once, as a single large-scale percept or conception. This is somewhat akin to how we are able to engage a work of visual art (a painting, photograph or sculpture) in its entirety, as a single impression of many dimensions, all at once. In observing a sculpture, for instance, its elements and form (composition in the visual arts) of their presentations do not change while one is examining the work—though one’s gaze may linger at any point, view the object from any angle, examine it up close or from afar, or even see the work in a different setting (context), with different lighting, or under different circumstances. The many aspects of composition related to the sculpture are as rich in detail and variety as the elements of the track—except they do not unfold over time.

This brings us to define this sense of ‘form’ as a conceptualization of the song, as if perceived in total, all at once.18 The record’s form is conceptualized in an open consciousness, perceived as an object like a sculpture—but now a sound object, existing out of time. This object is multidimensional, faceted, textured; the record is crystallized into a fundamental shape that represents all that makes it unique, along with its essence, its core impression; its time stilled, time passage simply becomes but one of its qualities. It is a conceptual or mental representation of the whole that contains what unfolded temporally but is not chronological, or episodic memory, and that contains all different types of patterns, at all structural levels, in all three domains, but of no assigned significance. The significance of materials and message, energies and expressions that establish its core impression are unique to the individual track.

The record might now be conceptualized, observed and understood as if by processing all of its variables all at once, into a single expressive, aesthetic object. The record becomes a single, global, multidimensional object or manifestation. The recorded song becomes one, as if all is sounding simultaneously, and in an instant; the shape of the song and the essence of its character and content are recognized within a single, broad, rich understanding; a manifestation of what the song ‘is.’

The idea of the sound object helps us understand music out of time, crystallized into a singular singular whole, into one complex aural image. All of the song’s multidimensional characteristics can be examined while considering it as a whole, all at once as if it were a physical object. The complex composite sound itself is observed as if suspended from time, crystallized. In this concept of ‘form,’ the sound object is the perception of the whole recorded song in an instant, with time stilled.