2

VERY REAL THREATS TO A VERY FRAGILE EGG

Running Out of Money, Risk, and Fees

“Nest egg.” What a strange phrase this is! According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the official definition of “nest egg” is: an amount of money that is saved over a long period of time in order to pay for something in the future.

These days, the term “nest egg” usually refers to our life savings for our hopeful, one-day retirement. However, there is evidence of the term being used as far back as the late 17th century to refer to saving money for any specific long-term goal. The term comes from the practice of leaving a real or fake egg in a hen’s nest in order to induce her to continue laying her own eggs there.

I find it fascinating that something as crucial as saving for retirement, or for our older years in general, has become metaphorically attached to something as fragile as an egg. Can you think of anything more fragile? This is why the “egg-drop challenge” is so popular for kids’ science classes and why the “egg-toss” game is so fun (and messy!).

We’ve all had the experience at some point in our lives of accidentally dropping a raw egg on the floor. One of my most vivid middle-school memories has to do with just that. I was in “home ec,” which really meant cooking and sewing. (Strange, now that I think about it, that “home economics” didn’t involve classes on money management, budgeting, or economics. But anyway, I digress.) One day in home ec, we were cooking something that involved eggs when one of the girls in my class left her egg on the counter, and . . . off it rolled. Splat! I remember this so well because the teacher chastised her loud enough for the whole class to learn a lesson from her apparently unforgivable mistake. The teacher boomed, “An egg is fragile! You must protect your egg!”

You must protect your egg. But what if it’s your nest egg, and it’s exposed to the threats that are seemingly beyond your control? In this chapter, I will show you what these dangers are so that you can be more aware and motivated to take the steps necessary to protect your own fragile egg. The rest of this book, including strategies in this chapter, are about protecting your nest egg and retirement prospects. The three biggest threats are:

1. Running out of money

2. Risk

3. Fees

![]()

Truth will ultimately prevail where there are pains taken to bring it to light.

GEORGE WASHINGTON

Founding Father and first president of the United States (1732–1799)

THREAT #1: RUNNING OUT OF MONEY

Over the course of your life, how many times have you been advised or even admonished to save for retirement? These days, we’re bombarded from all sides with warnings to build our nest egg. Whether it’s through advertisements from financial institutions, general stories in the news, or pop-culture financial “gurus,” the message is consistent: we’re doing a terrible job of saving and we need to do better, or else . . .

However, there’s an elephant in the room that nobody seems to want to talk about. The problem is this: When it comes to saving for retirement, there simply is no way to really know how much you will need. There are countless retirement calculators out there, but no matter how sophisticated they are, these calculators are likely to fail you.

For starters, it is simply impossible to know exactly how long you will live. You could look forward to retirement your whole life, only to have a sudden illness or accident rob you of all that you’ve stashed away, and all the time and forsaken lattes and dinners out that these savings represent.

On the other hand, you could outlive your savings. Since people are generally living longer than ever before, your nest egg will need to stretch further in retirement than it would have had to for our parents and grandparents (those of whom who were without pensions, that is).

If you are worried, you are not alone. In fact, the degree to which feelings of uncertainty are plaguing us is evidenced by the following stats. (The stats vary somewhat, but the gist is consistent.) A poll by the AARP found that 61 percent of adults feared running out of money in retirement more than death itself.1 This poll also found that the majority of people between ages 44 and 54 are worried that they won’t be able to cover basic living expenses once they retire. More than a third of those polled had no idea whether, at the end of the day, their savings would be enough. Similarly, the 15th Annual Transamerica Retirement Survey by the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies found that 70 percent of female and 63 percent of male workers believe they could work until age 65 and still not have enough money saved to safely retire.2 A recent survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute found that 82 percent of working adults believe they won’t have enough money to live on comfortably throughout their retirement years; 71 percent feared not having enough money to take care of their basic expenses in retirement.3

Adding to this fairly endemic level of concern, there is no way to really know what your standard of living or necessary expenses will be once you stop working. Many financial advisers make certain assumptions in their calculations. For example, many assume you will spend less in retirement than you do now. In reality, retirees frequently find that with more time on their hands, they tend to spend more, whether it’s on travel, dining out, or doing things they enjoy that cost money. As people age, they also tend to have more health-related expenses, sometimes many more. As our homes and vehicles age, we can expect more of these unexpected expenses, not less. Retirement calculators are not crystal balls, and yet they are often treated as such when it comes to planning for life after leaving the world of steady income. While we can take some measures to try to safeguard our financial future, we can’t ever fully plan for the unexpected. Unforeseen expenses will come up.

![]()

I can’t change the direction of the wind, but I can adjust my sails to always reach my destination.

JIMMY DEAN

American country-music singer (1928–2010)

A Million Dollars?

Many people assume that a million dollars is the golden ticket for retirement. However, this number has no real meaning, especially given the uniqueness of everyone’s circumstance and lifestyle. According to popular investment advice, retirees can live on $40,000 per year if they take out 4 percent of their one million dollars each year.4, 5 However, according to Jeff Sommer, a New York Times financial columnist, even if that million bucks is invested in so-called risk-free municipal bonds, your chance of outliving your savings is a whopping 72 percent.6

But most people don’t have a million dollars. Not even close. It’s just too hard to save. Plus there is the ever-present reality of mutual-fund and financial-adviser fees, which you will read about under Threat #3 later in this chapter.

In 2015, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) conducted a study and found that half of adults ages 55 and older have no retirement savings whatsoever and one quarter have less than $148,000.7 The Economics Policy Institute found that the average person with a 401(k) is on track to retire with only 20 to 40 percent of what they need to maintain their current standard of living.8

The problem is that we are approaching the idea of retirement from the wrong angle. It’s just not practical for many individuals to save enough to safely retire, especially when there’s no way of safely knowing how much is enough.

From this point forward, rather than feeling bad about how you’re doing in this department, and instead of burying your head in the sand and hoping it will all turn out okay, I encourage you to start thinking outside the box. Think beyond the nest egg.

![]()

Most people cannot save their way to retirement today.

KIM KIYOSAKI

Author of It’s Rising Time

THREAT #2: RISK

Whether it’s a first date or a wedding, there’s always a chance that things might not go as planned. This is risk. When we hop in the car to drive to the post office, there is risk. Even if it’s quite small, we risk getting in an accident on the way there. And if we do get in an accident, our risk of suffering injury or death can be dramatically lessened by buckling up. Risk speaks to the unknown.

This section will go into the three main risks associated with mutual fund–based retirement accounts:

1. The stock market

2. Financial advisers

3. Electronic and cyber-related risks

Keep in mind as you read this section that, in spite of these risks, I’m not proposing we stop contributing to our retirement accounts. Indeed, we should continue to fund our retirement accounts for many of the reasons explained in chapter 1, in the section “Benefits of Traditional Retirement Vehicles,” just as we should continue using our car to do whatever we need to do. I’m simply suggesting that you understand the risks and wear your seat belt. And in this area of life, diversification is your seat belt. Diversification is about doing something completely different from what you are currently doing, in addition to doing what you are currently doing, in order to lessen risk as you prepare for the future. Simply said, it is about not putting all your eggs in one basket.

![]()

Anyone who thinks there’s safety in numbers hasn’t looked at the stock market pages.

IRENE PETER

American writer

Risk #1: The Stock Market

We all know there is risk in the stock market. We’ve seen our accounts plummet (and then bounce back sooner or later). We understand that recession is a normal part of the business cycle. We understand the risk.

And while the stock market does tend to trend upward over time, the question is: What if . . . What if all your retirement savings are tied up in the stock market? What if the market drops just when you plan to retire? What if it drops later on, like in your seventies, when you are mandated to take withdrawals regardless of the price of your stock? What if the dip is major and long-lasting?

When it comes to the stock market, risk is defined as the chance that an investment will do worse than expected, or that we will lose money. This is because the entire system is built on the premise of buying shares at one price and selling at a higher price. And, as much as we like to reassure ourselves that the market always bounces back, the truth is that we’re playing with risk. This is why financial advisers ask you about your “risk tolerance,” and why we have low-, medium-, and high-risk stocks.

Risk in the stock market is not about whether it will bounce back. Risk is about timing. Because the stock market is intimately tied to risk, and because it naturally moves in up-and-down cycles, the stock market has an odd way of working when it comes to retirement. Not completely unlike the lottery, it creates winners and losers at random. The difference is that winning and losing in the stock market depends largely on your timing. If you are retiring and the market is up, and stays up, you’re a winner. If the market falls after you’ve stopped working, you’re not.

To compound the issue, the inherent risk in the stock market is actually greatest for those who are closest to retirement. Even those with moderate to substantial amounts invested are subject to this risk. In the words of Stephen Gandel, author of Time magazine’s seminal article on the retirement crisis:

In what must seem like a cruel joke to many, the accounts proved the most dangerous for those closest to retirement. During the market downturn, the 401(k)s of 55-to-65-year-olds lost a quarter more than those of their 35-to-45-year-old colleagues. That’s because in your early years, your 401(k)’s growth is driven mostly by contributions. You control your own destiny. But the longer you hold a 401(k), the more market-exposed it becomes. It’s a twist that breaks the most basic rule of financial planning.9

The financial industry has attempted to convince us that our 401(k) plans will make us wealthy by the time we are ready to retire, certainly wealthy enough to retire. And yet in October 2008, when the stock market tanked, triggering what is known as the Great Recession, more than seventy million Baby Boomers on the brink of retirement lost vast sums of their life savings. In fact, nearly everyone with a 401(k) saw their accounts tumble by 25 to 50 percent overnight, depending on how they had their investments allocated.10

As I described in chapter 1, our society has simply veered into this nest-egg way of planning for retirement; it was never planned, researched, modeled, or tested. So in essence, at the expense of those early Baby Boomers who happened to be without a pension, the Great Recession constituted a test drive of the 401(k).

And sadly, the road test failed for those retiring in or around 2008. Many people were forced to delay their retirements or cancel them altogether, depending on circumstance, while others were forced out of their jobs and thrust into “early retirement” as companies trimmed down their workforces. It is a cruel reality that when the economy suffers, companies can be quick to let go of workers, and often older workers are the first to go. Losing one’s job late in life—but earlier than planned—can mean losing nearly everything at once: daily routine, community of friends and co-workers, and pride. This also comes with the possible loss of promised pension benefits and retirement account values.

![]()

The main purpose of the stock market is to make fools of as many men as possible.

BERNARD BARUCH

Stock market financier and adviser to Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt (1870–1965)

The last thing to point out here is that as Baby Boomers continue to retire over the next couple of decades, they will collectively be pulling vast sums of money out of the stock market. This will occur in part by choice, part by necessity, and part by mandate (see the section on the RMD from chapter 1). Do with this information what you may; however, in the sage words of Robert Kiyosaki, author of Rich Dad Poor Dad: “You do not need to be a rocket scientist to know that it is hard for a market to keep going up when more and more people are getting out.”11

The point of this section is not to scare you off from investing in your 401(k), IRA, or other type of retirement account or mutual fund. The point is to help you become aware of the risks of investing solely in these vehicles in the hope of your accounts appreciating in value. Just as you might have a fire extinguisher in your kitchen for an event that may never happen, you need a backup plan for retirement. A retirement portfolio that is truly diverse includes types of assets that entail completely different types of risk from each other, as you’ll see in the next chapter.

![]()

October: This is one of the peculiarly dangerous months to speculate in stocks. The others are July, January, September, April, November, May, March, June, December, August, and February.

MARK TWAIN

Risk #2: Financial Advisers

Since this section is about risk, it would be a disservice not to mention financial advisers here. After all, we collectively entrust our advisers with billions of our dollars each year. In other words, we delegate risk to them in the hope that they will know more about investing than we do. Many of us may even expect them to “beat the market.”

We’ll cover fee structures of financial advisers and fee-related risk in the next section. However, it is worth mentioning here that you need to really trust your financial planner. By trust, I mean having confidence in both their level of competence and their honesty. I don’t mean the warm, fuzzy feeling that comes from their enthusiasm, friendliness, and apparent interest in your kids or favorite sports team! Nor does it mean the sense of confidence inspired by their no-nonsense professional disposition. Good eggs and bad eggs look the same on the outside. This goes for your financial planner, too. Unethical, unscrupulous, or simply bad financial planners present themselves just as well as the ones who are knowledgeable, impartial, and honest.

Financial planners have a range of education, experience, and expertise. Some are trained by the companies they represent, while others are independently credentialed as a Certified Financial Planner. Some receive a percentage of your investments whether or not they go up or down in value, while others provide investment advice on an hourly basis.

If your investment adviser claims that he or she can “beat the market,” run away fast. It is now widely accepted that advisers are not able to outperform the market. In fact, given the often-exorbitant fee structure charged by some advisers, John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, and other finance experts, assert that most people would be better off investing in a low-fee index fund, themselves, than investing with a financial planner.12,13 The last section in this chapter, “Threat #3: Silent but Deadly Fees,” is a must-read because it shows you exactly why millions of people are being robbed by retirement-account companies and financial planners . . . and how to find out if you are one of these unlucky ones.

![]()

The difference between playing the stock market and the horses is that one of the horses must win.

JOEY ADAMS

Comedian and New York Post columnist (1911–1999)

A Word About Unscrupulous Financial Advisers

When it comes to unscrupulous financial advisers, the name “Bernie Madoff” often is the first to come to mind. After all, he destroyed the financial security and retirement dreams of thousands of individuals by swindling them out of billions of dollars collectively. He also wiped out charitable organizations and their beneficiaries, owners, and employees of small businesses, and customers of the banks that had invested with him.14,15,16 Madoff ran the largest and most infamous Ponzi scheme in history.

While the scale of Madoff’s scam is unparalleled, and while we may be inclined to think that this kind of crime only happens to “other people,” the undeniable truth is that smaller-scale and potentially less obvious financial scams are around us all the time. In fact, roughly one Ponzi scheme was uncovered every six days in the United States in 2015.17

In an effort to help everyday investors like you and me, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has published a list of Ponzi-scheme red flags, as shown below:

1. Promises of high returns and little to no investment risk

2. Overly consistent returns

3. Investments that are not registered with the SEC or state regulators

4. Sellers that are unlicensed (either companies or individuals)

5. Secretive and/or complex investment strategies

6. Issues with producing timely statements

7. Errors and/or inconsistencies on statements

8. Difficulty receiving payments

9. Pressure to “roll over” gains into other investments18

Scam artists can be unscrupulous financial advisers, insurance brokers, and annuity salespeople. I spoke with an elderly widow, whom I will call Charlotte, who had been conned by her annuity salesman into buying a policy with a well-known insurance company. After seemingly elite treatment, a physical exam, and an extensive application, the company required $20,000 up front, plus another $20,000 each year thereafter. Charlotte moved forward and generously enrolled in this policy so that her grown kids would not have to pay taxes on her estate upon her death. Her problem was that this $20,000 annual price tag would have substantially dented her limited nest egg and jeopardized her chances of outliving her own money or even having anything left in her estate to be taxed on at all.

Risk #3: Electronic and Cyber-Related Risk

This section on risk was not fun to write. I’m sure it will be equally depressing to read. However, back to the analogy of the fire extinguisher in your kitchen, it is important to acknowledge that having all your money in virtual accounts, with online accessibility, comes with a certain level of risk. There are many different types of electronic and cyber-related risks, and the lines between them are fuzzy. However, there are three general categories:

1. Identity theft and “ransomware”

2. Cyberterrorism and cyberwarfare

3. Technology errors and frozen accounts

Any mutual-fund manager or investment adviser will tell you that you need to diversify. They will inform you about high- and low-risk stocks. They will tell you about bonds. But what most won’t tell you, what most may not even recognize, is that diversification must go beyond virtual accounts. True diversification requires diversifying across both electronic and non-electronic accounts. What is a non-electronic account? It is real estate. It is a house or building that you can walk into, touch, and improve with your own hands.

Identity Theft and Ransomware

According to the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, identity theft is one of the fastest growing crimes. It entails the fraudulent acquisition and use of a person’s private identifying information for financial gain. Just as your bank accounts and credit cards are at risk of being wiped out by a malicious computer hacker, your retirement accounts are also at risk. While the hacking of retirement accounts currently seems to be relatively rare as compared to credit card and bank accounts, their very online nature and virtual existence make them prime targets. Recognizing this, Steve Vernon of CBS Money Watch has provided a resource for safeguarding your retirement accounts at the following website: www.cbsnews.com/news/how-to-protect-your-retirement-savings-from-identity-theft-and-internet-fraud/.19 In addition to the tips he provides on protecting your retirement accounts from identity theft, think about building something separate, something tangible, something that is not vulnerable to a computer hacker at all.

Ransomware is a whole new breed of computer hacking. It involves a type of malicious software designed to block the owner’s access to a computer system until a sum of money is paid as a ransom. It can be aimed at individuals, businesses, and governments. According to a National Public Radio segment, fourteen hospitals in the United States were targeted with ransomware in the spring of 2016.20 The medical files were literally held hostage, compromising patients’ health, until a large sum of money was paid for their release. Similar incidents have been reported by a police department in Massachusetts, a café in Maryland, and an incident that affected over six thousand Mac computer users.21 In each case, the malicious hackers demanded, and received, money for the release of files.

Cyberterrorism or Cyberwarfare

There are numerous examples of hacks into governmental and nongovernmental computer networks by foreign governments or entities. For example, there was the foreign infiltration of the U.S. electrical grid in 2009.22 There was the attack on Sony Pictures’ computer system in 2014 in which personal employee information was leaked to the public.23 And there was the massive attack on the U.S. government with the stolen identities of an almost unfathomable 21.5 million federal employees in 2015.24

Cyberterrorism and cyberwarfare involve threats to our national security and stability. They are malicious acts by terrorists or nations to penetrate computers or networks for the purpose of causing massive disruption. The concern, which is not insignificant, is that a large-scale cyber-attack could seriously damage the financial-services industry or other aspects of our national infrastructure.25,26

Technology Errors and Frozen Accounts

Let’s face it. Computers are fallible. They break down. Software sometimes does funky stuff. And on occasion, they are attacked by malicious viruses. When it comes to our own computers, technology breakdown—in one form or another—is not only possible, it is almost inevitable. In fact, we’ve almost come to expect it. This is why we go to great lengths to protect ourselves from our own computers. We back stuff up. We download the latest anti-virus software. We buy a new computer every few years (usually after our last one crashes!).

Banks, mutual-fund companies, and even the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) all deal with the same issues, but on a larger scale. They have more (way more!) stuff at risk. They have better (way better!) anti-virus software and firewalls. And they have more bad guys (way “badder”) trying to hack into their systems. What this means is that, even at the level of the NYSE, things have the potential to go awry.

On August 1, 2012, tens of thousands of accidental stock trades flooded the stock market. This major “oops” moment was caused by a simple software glitch at a high-speed electronic trading company, Knight Capital, in which legitimate stock trades were each multiplied accidentally by one thousand. The error was detected and halted within forty-five minutes, but it caused the company’s stock price drop from $10.33 to $2.84 per share.

This was not the only time a technical issue sent the stock market flying into a tailspin. In July 2015, the NYSE shut down for nearly four hours. At this writing, it was still unclear whether the shutdown was in response to a technical error or cyberthreat.27

Simultaneously, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the citizens of Greece saw their bank accounts essentially frozen by the government in an attempt to fix the Greek government debt crisis. Banks and the stock market were shuttered, with ATMs being the only source of cash. Greeks were limited to withdrawals of 60 Euros ($66) per day.28,29 While these “capital controls” were only expected to last a couple of weeks to a month, two years later, these ATM withdrawal limits and other capital controls were still in effect and are expected to remain so indefinitely.30

You take so many measures to protect your own computer and personal information. Yet, because of cyber-related risks beyond your control (identity theft, ransomware, cyberwarfare, technology snafus, and frozen accounts), it must be acknowledged that virtual assets do come with a certain level of risk. And having all your money—from your bank account to your retirement account—residing electronically escalates your level of risk. Failing to diversify into tangible assets (like real estate) is like driving without a seat belt or having no fire extinguisher in your kitchen. And in this technology-dominant era, the best safeguard is one that is not, also, technology-based.

THREAT #3: SILENT (BUT DEADLY) FEES

The third threat goes beyond risk into the land of certainty. What you’re going to read next will floor you. Seriously, if you are not sitting on the floor right now, you might want to take a moment to get there in order to prevent injury.

Have you ever heard that saying about casinos? “The house always wins.” Well, when it comes to your retirement accounts, there are good ones and, well . . . let’s just say, there are casinos.

The fees you pay to your retirement or mutual-fund company can be devastating. If you add up all the fees and if they are under one half of 1 percent, then you can feel confident that you have a really good plan.31 If you are between half a percent and 1 percent, then you have an okay plan. If your plan’s fees are between 1 and 2 percent, then you are losing money. Anything more than 2 percent and you’re being robbed.

While fees that add up to a couple of percentage points may not sound like a lot, they translate into big bucks. Really big bucks. In an attempt to help consumers understand whether their plan is a good egg or a bad one, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) published information, in 2013, on the topic at www.dol.gov/ebsa/publications/401k_employee.html#section9 and explained the impact of fees by way of the following example:

Assume that you are an employee with 35 years until retirement and a current 401(k) account balance of $25,000. If returns on investments in your account over the next 35 years average 7 percent and fees and expenses reduce your average returns by 0.5 percent, your account balance will grow to $227,000 at retirement, even if there are no further contributions to your account. If fees and expenses are 1.5 percent, however, your account balance will grow to only $163,000. The 1 percent difference in fees and expenses would reduce your account balance at retirement by 28 percent.32

This is just one example. The impact of the fees depends on how long you invest, whether you continue to make contributions, and your average rate of return. And of course, more than anything else, the impact depends on the fees that are charged by your plan.

John Bogle, the aforementioned founder of Vanguard and author of many investment-related books, has been aiming to get the word out about fees for a while. On the PBS Frontline episode “The Retirement Gamble,” he said:

What happens in the fund business is that the magic of compound returns is overwhelmed by the tyranny of compounding costs. It’s a mathematical fact. There’s no getting around it.

He gives an example of a mutual fund with a 7 percent average return and a 2 percent annual fee. Over fifty years of investing, the fund will have lost almost two thirds of its value!33

The impact of seemingly small fees boils down to simple math. In this example, the 7 percent rate of return will have been essentially reduced to a 5 percent rate of return. The remaining 2 percent rate of return goes directly toward your company’s bottom line. From the consumer’s perspective, the 2 percent loss is not even noticeable. It just quietly comes out of the balance each month, often not even showing up as a line item.

As James Ridgeway, former Wall Street Journal and Mother Jones journalist, states: “Fees have always been one of the built-in scams of mutual funds.” He quotes Representative George Miller (D-California), chairman of the House Committee on Education and Labor, as saying during a February 2009 hearing on retirement security,

Wall Street middlemen live off the billions they generate from 401(k)s by imposing hidden and excessive fees that swallow up workers’ money. Over a lifetime of work, these hidden fees can take an enormous bite out of workers’ accounts.34

In other words, the mutual-fund and retirement-account companies with high fees are literally banking on your not paying attention.

![]()

The 401(k) mutual fund is one of the only products that Americans buy that they don’t know the price of. It’s also one of the products that Americans buy that they don’t even know its quality or know how to judge its quality. It’s one of the products that Americans buy that they don’t know its danger.

PROFESSOR TERESA GHILARDUCCI

Professor of Economics at The New School and author of When I’m Sixty Four: The Plot Against Pensions and the Plan to Save Them, on PBS Frontline (April 23, 2013)

An Example of How Fees Work

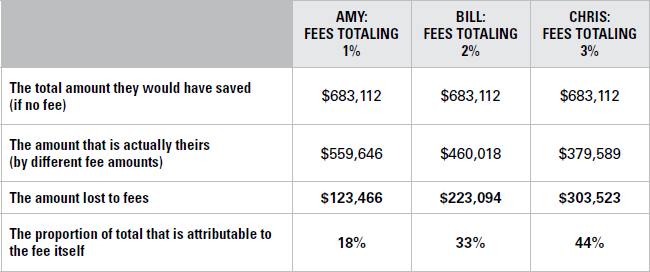

As another example of how this works, let’s assume that three triplet siblings (let’s call them Amy, Bill, and Chris) just celebrated their 40th birthdays together. Toward the end of the bash, and feeling slightly uninhibited, they ended up talking money with each other. As they shared their situations, it dawned on them that their retirement-savings situations were shockingly similar. That is, all except for one small detail hidden in the fine print of their companies’ prospectuses. The amounts they were paying in fees to their companies were 1, 2, and 3 percent, respectively. Other than the varying fees, Amy, Bill, and Chris each had retirement account balances of exactly $50,000, were invested in mutual funds with a 7 percent average rate of return, planned to make no additional contributions, and hoped to retire at age 67.

Table 2.1 and Figure 2.1 show the impact of the different fees on Amy’s, Bill’s, and Chris’s future account balances at age 67. For Amy, the 1 percent in fees will dent her ultimate retirement savings by 22 percent (one fifth). She was pretty depressed about this until she learned that Bill’s 2 percent in fees will eat up 40 percent of his entire account balance in the end. Chris, on the other hand, left the party thoroughly depressed (though enlightened). Chris realized that if he stays with his current plan, the fees of 3 percent will consume more than half of his total savings by the time he hopes to retire! You can see from Table 2.1 that—in the end—the mutual-fund company will actually make more money than Chris will . . . when it was Chris’s money to begin with! And when Chris was the one shouldering all the risk! It’s almost unbelievable.

The next day, Chris took action to find an index fund with a new company with fees, at less than 1 percent, that were even lower than Amy’s. Being the good brother that he is, he quickly informed his sibs and they all made the change together to the consumer-friendly mutual fund.

TABLE 2.1. TOTAL RETIREMENT SAVINGS AND TOTAL LOST TO FEES BY AGE 67

(Assuming $50,000 Balance by Age 40, No Additional Contributions After Age 40, And a 7% Average Rate Of Return)

FIGURE 2.1. DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE AMOUNT SAVED WITHOUT FEES VERSUS SAVED WITH FEES RANGING FROM 1% TO 3%

Table 2.1 shows exactly how the 401(k) and IRAs are failing workers, using our hypothetical triplets as an example. Figure 2.1 is a graphical representation of the same information. This graph shows the difference between what Amy, Bill, and Chris would have accrued after twenty-seven years with no fee (the solid and striped sections, combined, at $310,692), compared to the amount they would have built up with fees of 1, 2, and 3 percent (shown as the solid section on the graph). Another way of looking at this graph is that the striped section represents the total amount of money that Amy, Bill, and Chris would have lost to their mutual-fund companies under their different fee scenarios (ranging from $69,576 to $166,524).

I should note that if Amy, Bill, and Chris had continued making contributions to their plans until age 67, rather than stopping at age 40, they would have each amassed much more money (in spite of also bringing in more money for the mutual-fund companies). In fact, as you can see from Table 2.2, each of their total account values, as well as the amounts that they would have been able to keep for themselves, would have more than doubled.

TABLE 2.2. TOTAL RETIREMENT SAVINGS AND TOTAL LOST TO FEES BY AGE 67

(Assuming Continued Contributions of $5,000 per Year After Age 40)

Table 2.2 is good evidence for the importance of continuing to make contributions to your retirement plan or mutual fund. However, it is equally good evidence for the importance of taking a close look at your accounts to ensure that you are in a low-fee plan. Find out the annual operating expenses (also called the expense ratio) and all other fees, using the method in the next section, and make any necessary changes to ensure that you are in a low-fee plan, as soon as humanly possible.

Figure Out Your Plan’s Fees and Their Impact

You can determine the damage that fees will have on your own mutual fund and retirement accounts. To do this, you need to gather your numbers and simply plug them into the calculator at the following website: www.401kfee.com. The hard part will be gathering your numbers. Some companies make it almost impossible to determine your fees, while others make it a bit easier. Sometimes these fees are either not disclosed, disclosed only to your employer, or disclosed in such a confusing way that they can be impossible to interpret.35,36

You have a few options when it comes to finding out what your fees are. First, you can go through the mutual-fund-company prospectus that comes in the mail. Look for a number that is expressed in the form of a percentage. Once you’ve found the percentage, check to see if this is called an “expense ratio” or “annual operating expenses.” If it is, you’ve found the right number. These annual operating expenses may not encompass all the fees that you might be subject to with your plan; however, they are a good starting point.†

A second option is to call the company to ask about the fees. However, don’t put too much weight on anything they say over the phone. Ask them to send you the prospectus or some other document so you can see it in black and white.

Finally, you can look up the fees online. There are at least two free resources for checking out many plans’ fee structure. The company Brightscope is an independent financial information and technology site aiming to bring “transparency to opaque markets.” Their site (www.brightscope.com/ratings/) provides the expense ratios for different funds. For comparison, it also provides information on how your fund compares to others in the same category.

The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) also provides assistance in determining fees through its site: http://apps.finra.org/fundanalyzer/1/fa.aspx. On this site, fees are called “annual operating expenses.” FINRA also lists any front-end, back-end, or redemption fees that may be associated with your plan. However, the site also discloses that “the results do not reflect the application of other fees that may apply, such as ETF commissions, exchange fees, or account maintenance fees. Had these fees been considered, your costs would be higher and account values lower.”

It is important to note that the fee information from both sites also does not account for any fees that your financial planner charges, if you have one. I’ll go into this redundancy a bit more in the next section. For both websites, when you enter the ticker symbol for your fund, you receive instantaneous results. Note that the results from the two sites will probably not be identical, so it is a good idea to look at your fees both ways, and go with the higher one, knowing that some fees never make it into the calculations.

Finally, it is worth noting that if you are unable to locate your plan’s fees, either through a prospectus or either of the above websites, you may have a dud of a plan. Meaning, as I discuss in the next section, get out.

Getting the Best Return on Your Retirement Accounts

The simple exercise that I proposed in the last section will either reassure you that all is well with your accounts, or it will arm you to take action. If you have one retirement account, you can evaluate whether you want to stay, or switch to a lower-fee plan. If you have more than one plan, say from past and present employers, you could save potentially tens of thousands of dollars in redundant fees alone by consolidating your funds into the one with the lowest fees. Or, if none of your plans have fees under 1 percent, find a plan that does and move all your accounts into that new plan. There is no need to “diversify” across different fee amounts. It is always best to ensure that you are in the lowest-fee plan possible. Talk to an accountant before moving your funds across plan type (Roth, non-Roth, 401[k], IRA, etc.) to understand any taxes or penalties based on your own personal situation.

Your retirement account is a critical part of a diverse retirement plan. The key is to make sure you are in the right one. As I shared in chapter 1, there are several benefits to employer-sponsored retirement plans. The direct-deposit feature makes it almost effortless to save money. If your workplace provides matching funds, then this is essentially free money for your account. Finally, as I share later in this book, once your account builds to some value, you can leverage those funds to purchase income-generating real estate if you like, and then pay yourself back, with a net result of two asset classes (your retirement account plus a rental property) rather than simply your one retirement account. Again, for all these reasons, the take-home point from this chapter is this: Don’t ditch your 401(k) or other retirement plan, and don’t stop your contributions, but do make sure you are invested in the right one.

Fees and Your Financial Adviser

Many people swear by their financial adviser. After all, most of us don’t have the expertise—or even the interest—to safely make our own investment or retirement-planning decisions. And while this may be true, especially when it comes to understanding the technicalities related to the stock market, bonds, annuities, and the like, there are two very important concepts that everyone should understand. How do financial planners get paid? And, to whom are they are loyal? This section goes into these two critical questions.

As you read this section, also keep in mind another critical question. I will share the answer with you toward the end, but for now, just see if the answer bubbles up on its own. The question to contemplate is this: Why don’t most financial planners ever talk about investing in real estate?

According to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, there are true investment advisers and there are “broker-dealers” who are, quite literally, salespeople. It is difficult to tell them apart because both types go by the term “financial adviser” or “financial planner,” and both types market themselves in ways that emphasize the financial-advisory aspect of their services.37 Where it gets confusing is that, under U.S. law, broker-dealers are not required to make their customers aware of any conflict of interest that could bias their recommendations.38 This means that, by law, broker-dealers are allowed to be secret salespeople with no legal obligation to act in the best interests of their clients. They are merely required to find investments that are “suitable” enough.

Helaine Olen, author of Pound Foolish and former personal finance columnist for the Los Angeles Times, stated on the PBS Frontline episode “The Retirement Gamble” (April 23, 2013) that the term “financial adviser” is “a term that means almost nothing. It is somebody who might be a financial planner, or it could be a broker who is really a salesperson.”

![]()

We have a system today where anybody can hold themselves out as an expert. They call themselves retirement planners, financial planners, advisers, et cetera. We don’t have a standard way that the consumer can figure out who has the expertise to provide advice.

PHYLLIS BORZI

Assistant Secretary of Labor, 2013, U.S. Department of Labor, on PBS Frontline (April 23, 2013)

At roughly 85 percent, the vast majority of “financial advisers” are registered as broker-dealers.39,40 These salespeople usually represent one or more companies, and they are paid by commission to sign you up for certain products even if those products are not necessarily in your best interest, as long as they are suitable enough.41,42 Their decisions can be swayed by the product types that offer the best commission, or by the products that have sales-target incentives in terms of the number of customers they enroll.43

A 2015 White House report titled The Effects of Conflicted Investment Advice on Retirement Savings found that the advice provided by broker-dealers is estimated to cost individuals an average of 1 percent in fees, translating to a 25 percent loss in total portfolio accumulation, on average.44 Now that you understand the impact of fees (from earlier in this chapter), you can see that this additional 1 percent in fees due to conflicted investment advice is on top of the mutual-fund fees that were just discussed in the examples of Amy, Bill, and Chris.

On top of that, have you ever wondered how your financial planner makes his or her money? If your adviser is a broker-dealer, you can be fairly certain that they are taking a slice of your annual return in the form of fees. Again, take Amy, Bill, and Chris. Their mutual-fund fees were 1, 2, and 3 percent, respectively, and their rates of return were—in truth—6, 5, and 4 percent, respectively (not the 7 percent that was advertised). Now imagine that, instead of either enrolling in an IRA or mutual fund on their own, or enrolling in their work-sponsored plan, they had enlisted the help of a financial adviser to invest their money in a mutual fund for them. If that adviser charges 1 percent in fees, then in the end, Amy would actually be getting Bill’s earlier rate of return (5 percent); Bill would be getting Chris’s rate of return (4 percent); and Chris? Poor Chris would have a rate of return of only 3 percent (7 percent initial return minus 3 percent in plan fees minus 1 percent in fees from his financial planner). Finally, once we add in the cost of conflicted advice, just discussed, Amy’s, Bill’s, and Chris’s returns drop again to 4, 3, and 2 percent, respectively. Yikes.

![]()

The problem is that the investor puts up 100 percent of the money, takes 100 percent of the risk, and receives only 20 percent of the profits (if there are profits).

ROBERT KIYOSAKI

The truth is that in spite of the holiday cards, free dinners, and apparent interest in your life, many broker-dealing financial advisers don’t necessarily have your best interests in mind. Some may, of course. But for some, the lure of lifelong commissions is simply too powerful. And this also brings to light the answer to the question I posed at the beginning of this section: Why don’t they typically encourage real estate investing? It’s simple . . . they would have no piece of the pie, no commissions, no way to collect money on those types of investments. Plus, you would have less money to invest in their products that are laced with commissions and bonuses.

So, if roughly 85 percent of financial planners are broker-dealer types, what about the other 15 percent? These “fiduciary” financial planners are a completely different breed. These are true advisers, or “fiduciaries,” because they tend to be exclusively fee-based. In this context, fees are a good thing. What this means is that you pay your adviser either a flat fee or an hourly fee in exchange for their wisdom and guidance. These advisers represent their clients, only, rather than trying to walk the fine line between their clients’ best interests and their companies’ quotas and tempting commissions and bonuses. Since exclusively fee-based advisers do not receive commissions, they have no conflicts of interest. And, if there are any conflicts of interest, they are required by law to divulge them. Since they are free agents, they are true advisers rather than salespeople.

The one drawback of some exclusively fee-based advisers, however, is that their expertise may be limited to non-tangible (virtual or electronic) assets such as stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and real estate investment trusts (REITs). This lack of diversification into the world of tangible real estate is potentially problematic due to Threat #1, the danger of running out of money, and Threat #2, risk, as discussed earlier in this chapter. When selecting an adviser, you should always interview a few, before selecting one, to get a sense of how their ranges of expertise compare to each other. Pay attention to whether they bring up real estate on their own. If they don’t, be sure to ask questions to probe their comfort level with real estate investments.

By design, mutual fund companies, managers, and financial advisers (who are not exclusively fee-based) are set up to make lots of money, risk-free for themselves, while we shoulder all the risk. Since they make money in fees that are often collected as a percentage of their clients’ account balance as time goes on, they make actual money whether the accounts go up or down in value. In contrast, we only make theoretical money when the account value goes up, and we only make actual money if the investments are sold at a higher price than when they were purchased. This also means that, even though fund managers may be well meaning and may sincerely want their portfolios to do well, they don’t have a truly vested interest in their performance because it is not their skin in the game. In addition, the often-touted method of dollar cost averaging keeps our money flowing into the system and it keeps mutual-fund companies, managers, and advisers paid, one way or another, even when our accounts are losing value.

A SPECIAL NOTE FOR WOMEN

This is a special note for women, and men who care about their wives, mothers, daughters, sisters, and women in general. As you probably know, women tend to live longer than men. This means that if a woman retires at the same age as a man, she will probably need to stretch her savings further. On top of needing her nest egg to last longer, women typically reach retirement age at a disadvantage. This is due to many factors. It is well established that women continue to earn only 78 percent of men’s pay for comparable work.45 This means that, assuming men and women save the same proportion of their income each year, and since women typically make less than men, they also save less. For easy math, consider the example of a woman making $78,000 and a man making $100,000, both of whom sock away 5 percent each year in their retirement accounts. Five percent for the woman equates to $3,900, while five percent for the man is $5,000. Over thirty years, at 6 percent interest, the compounding effect of this (assuming no pay raises for either) adds up to a whopping $74,247 difference!

Unfortunately, however, this was a best-case scenario. The reality is that we can’t assume women and men save at the same rate. Research from the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies (TCRS) found that among employees of medium to large companies, fewer women than men work for employers that sponsor a 401(k) plan and, of those who do, women are less likely to participate.46 Furthermore, among those who do participate, women tend to auto-invest smaller percentages of their paychecks than men.47 A study by the Employment Benefit Research Institute found similar results among Individual Retirement Account (IRA) holders, with the female–male gap in savings being greatest among those who are closest to retirement age.48 There are probably many reasons for the lower savings rates among women, including the finding from the TCRS survey that female employees are focused on “just getting by” while more male workers prioritize “saving for retirement.”49 Taken together, these smaller percentages saved on lower amounts earned can add up to significantly lower savings by retirement age for women as compared to men.

What this means is that unless you do something radical, right now, surviving retirement as a woman may mean substantial sacrifice. You either sacrifice now (by forcing yourself to save more and living with less money and the risks described earlier in this chapter) or you sacrifice later (by adopting a lower standard of living in retirement or not retiring at all). Alternatively, you can use the strategies in this book to jettison yourself out of the limited-nest-egg way of thinking and into a sustainable cash-flowing asset . . . one that will never be used up and that will pay you every month, now, throughout your retirement, and “beyond” in the form of an inheritance for your heirs.

† The range of fees can include any of the following: back-end load (also known as deferred sales charge or redemption fee, when shares are sold), bookkeeping fees, finders’ fees, front-end load (when shares are purchased), insurance-related charges, legal fees, management fees (also known as investment advisory fees or account maintenance fees), revenue sharing, rule 12b-1 fees (ongoing), sales charges (aka: loads or commissions), shelf space, soft dollars, surrender and transfer charges, stewardship fees, transactional fees, trustee fees, wrap fees.