XML is like a VW Jetta: environmentally sensitive, slow, dependable, and terminally uncool. Lasts a lifetime. | ||

| --Nat Torkington | ||

As terminally uncool as XML may be perceived by some, one aspect of XML that certainly isn’t uncool is XML formatting. The reason is because you can dress up XML quite a bit by formatting it properly. There are two fundamentally different approaches to formatting XML documents, both of which you learn about in this hour and in the remainder of this part of the book. I’m referring to Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) and eXtensible Style Language (XSL). CSS is already in use around the Web as a means of formatting HTML web pages above and beyond the limited formatting capabilities of HTML. XSL, on the other hand, is purely designed for use with XML and is ultimately much more powerful and flexible than CSS. Even so, these technologies aren’t really in competition with each other. As you learn in this hour, they offer unique solutions to different problems, so you will likely find a use for each of them in different scenarios.

In this hour, you’ll learn

The basics of style sheets and XML formatting

When and why to use CSS and XSL on the Web

The practical differences between CSS and XSL style sheets

How to format a basic XML document using CSS and XSLT style sheets

Very few XML-based markup languages are designed to accommodate the formatting of content described with them. This is actually by design—the whole premise of XML is to provide a way of associating meaning to information while separating the appearance of the information. The appearance of information is very much a secondary issue in XML. Of course, there are situations where it can be very important to view XML content in a more understandable context than raw XML code (elements and attributes), in which case it becomes necessary to format the content for display. Formatting XML content for display primarily involves determining the layout and positioning of the content, along with the fonts and colors used to render the content and any related graphics that accompany the content. XML content is typically formatted for specific display purposes, such as within a web browser.

Similar to HTML, XML documents are formatted using special formatting instructions known as styles. A style can be something as simple as a font size or as powerful as a transformation of an XML element into an HTML element or an element in some other XML-based language. The general mechanism used to apply formatting to XML documents is known as a style sheet. I say “general” because there are two different approaches to styling XML documents with style sheets: CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) and XSL (eXtensible Style Language). Although I’d love to jump into a detailed discussion of CSS and XSL, I think a quick history lesson is in order so that you understand the relevance of style sheets. The next couple of sections provide you with some background on style sheets as they relate to HTML, along with how they enter the picture with XML. I’ll make it as brief as possible so that you can get down to the business of seeing style sheets in action with XML.

If it wasn’t for the success of HTML, it’s unlikely that XML would have ever been created. The concept of using a markup language to code information is nothing new, but the idea of doing it with a simple, compact language is relatively new. HTML is the first markup language that made it possible to code information in a compact format that could be displayed without too much complexity. However, HTML wasn’t intended to be a presentation language. Generally speaking, markup languages are designed to add structure and context to information, which usually has nothing to do with how the information is displayed. The idea is that you use markup code to describe the content of documents and then apply styles to the content to render it for display purposes. The problem with this approach is that it has only recently been adopted by HTML. This has to do with the fact that HTML evolved so rapidly that presentation elements were added to the language without any concern over how it might complicate things.

In its original form, HTML stuck to the notion of being a purely content-based markup language. More specifically, HTML was designed as a markup language that allowed physicists to share technical notes. Early web browsers allowed you to view HTML documents, but the browsers, not the HTML markup, determined the layout of the documents. For example, paragraphs marked up with the <p> tag might have been displayed in a 12-point Arial font in a certain browser. A different browser might have used a 14-point Helvetica font. The point is that the browsers made the presentation decisions, not the documents themselves, which is in keeping with the general concept of a markup language.

As you probably know, things changed quickly for HTML when the popularity of the Web necessitated improvements in the appearance of web pages. In fact, HTML quickly turned into something it was never meant to be—a jumbled mess of content and presentation markup. At the time it made sense to hack on presentation elements to HTML because it allowed for better-looking web pages. Another factor that complicated HTML was the “browser wars,” which pitted web browser vendors against one another in a game of feature one-upmanship that resulted in all kinds of new HTML presentation tags. These tags proved extremely problematic for web developers because they were usually supported on only one browser or another.

To summarize my HTML soapbox speech, we all got a little carried away and tried to turn HTML into something it was never intended to be. No one really thought about what would happen after a few years of tacking on tag after presentation tag to HTML. Fortunately, the web development community took some time to assess the future of the Web and went back to the ideal of separating content from presentation. Style sheets provide the mechanism that makes it possible to separate content from presentation and bring some order to HTML. Whereas style sheets are a good idea for HTML documents, they are a necessity for displaying XML documents—more on this in a moment. A style sheet addresses the presentation needs of HTML documents by defining layout and formatting rules that tell a browser how to display the different parts of a document.

Unlike HTML, XML doesn’t include any standard elements that can be used to describe the appearance of XML documents. For example, there is no standard <b> tag in XML for adding bold formatting to text in XML. For this reason, style sheets are an absolute necessity when it comes to displaying XML documents.

By the Way

Technically, you could create your own XML-based markup language and include any presentation-specific tags you wanted, such as <bold>, <big>, <small>, <blurry>, and so on. However, web browsers are designed specifically to understand HTML and HTML only and therefore wouldn’t inherently understand your presentation tags. This is why style sheets are so important to XML.

Style sheets aren’t really anything new to web developers, but they were initially slow to take off primarily due to the fact that browser support for them was sketchy for quite some time. Cascading Style Sheets, or CSS, represent the HTML approach to style sheets because they were designed specifically to solve the presentation problems inherent in HTML. Because CSS originally targeted HTML, it has been around the longest and has garnered the most support among web developers. Even so, only recently has CSS finally gained reasonably consistent support in major web browsers; all major web browsers now more or less offer full support for the latest CSS standard, CSS 2.

eXtensible Style Language, or XSL, is a much newer technology than CSS and represents the pure XML approach to styling XML documents. XSL has had somewhat of a hurdle to clear in terms of browser acceptance but the latest releases of most major web browsers provide solid support for a subset of XSL known as XSLT (XSL Transformation), which allows you to translate XML documents into HTML. XSLT doesn’t tackle the same layout and formatting issues as CSS and therefore isn’t really a competing technology. The layout and formatting portion of XSL is known as XSL Formatting Objects, or XSL-FO, and is unfortunately not as fully supported as XSLT. For the time being, XSL-FO is primarily being used to format XML data for printing. In fact, XSL-FO is commonly used to generate printer-friendly Adobe Acrobat PDF documents from XML documents.

Generally speaking, you can think of XSL’s relationship to XML as being similar to CSS’s relationship to HTML. This comparison isn’t entirely accurate since XSL effectively defines a superset of the styling functionality in CSS thanks to XSL-FO, whereas XSLT offers a transformation feature that has no equivalent in CSS. But in very broad terms, you can think of XSL as the pure XML equivalent of CSS. The next couple of sections explain CSS and XSL in more detail.

As you’ve learned, CSS is a style sheet language designed to style HTML documents, thereby allowing web developers to separate content from presentation. Prior to CSS, the only options for styling HTML documents beyond the presentation tags built into HTML were scripting languages and hybrid solutions such as Dynamic HTML (DHTML). CSS is much simpler to learn and use than these approaches, which makes it ideal for styling HTML documents, and it doesn’t impose any of the security risks associated with scripts. Although CSS was designed for use with HTML, there is nothing stopping you from using it with XML. In fact, it is quite useful for styling XML documents.

When a CSS style sheet is applied to an XML document, it uses the structure of the document as the basis for applying style rules. More specifically, the hierarchical “tree” of document data is used to apply style rules. Although this works great in some scenarios, it’s sometimes necessary to alter the structure of an XML document before applying style rules. For example, you might want to sort the contents of a document alphabetically before displaying it. CSS is very useful for styling XML data, but it has no way of allowing you to collate, sort, or otherwise rearrange document data. This type of task is best suited to a transformation technology such as XSLT. The bottom line is that CSS is better suited to the simple styling of XML documents for display purposes. Of course, you can always transform a document using XSLT and then style it with CSS, which is in some ways the best of both worlds, at least in terms of XML and traditional style sheets.

By the Way

On behalf of die-hard CSS advocates, I’d like to point out that you can transform an XML document using a scripting language and the Document Object Model (DOM) prior to applying CSS style sheets, which achieves roughly the same effect as using XSLT to transform the document. Although the DOM certainly presents an option for transforming XML documents, there are those of us who would rather use a structured transformation language instead of having to rely on custom scripts. You learn how to use scripts and the DOM with XML in Part IV, “Processing and Managing XML Data.”

Earlier in the hour I mentioned that XSL consists of two primary components that address the styling of XML documents: XSLT and XSL-FO. XSLT stands for XSL Transformation and is the component of XSL that allows you to transform an XML document from one language to another. For example, with XSLT you could translate one of your custom ETML training log documents into HTML that is capable of being displayed in a web browser. The other part of XSL is XSL-FO, which stands for XSL Formatting Objects. XSL-FO is somewhat of a supercharged CSS designed specifically for XML. Both XSLT and XSL-FO are implemented as XML-based markup languages. Using these two languages, web developers theoretically have complete control over both the transformation of XML document content and its subsequent display. I say “theoretically” because XSL-FO has yet to catch on as a browser rendering style sheet language, and thus far has been relegated to assisting in formatting XML documents for printing.

Because both components of XSL are implemented as XML languages, style sheets created from them are XML documents. This allows you to create XSL style sheets using familiar XML syntax, not to mention being able to use XML development tools. You might see a familiar connection between XSL and another XML technology, XML Schema. As you may recall from the previous hour, XML Schema is implemented as an XML language (XSD) that replaces a pre-XML approach (DTD) for describing the structure of XML documents. XSL is similar in that it, too, employs XML languages to eventually replace a pre-XML approach (CSS) to styling XML documents.

Although the general premise of style sheets is to provide a means of displaying XML content, it’s important to understand that style sheets don’t necessarily have complete control over how XML content appears. For example, text that is styled with emphasis in a style sheet might be displayed in italics in a traditional browser, but it could be spoken with emphasis in a browser for the visually impaired. This distinction doesn’t necessarily impact the creation of style sheets, but it is worth keeping in mind, especially as new types of web-enabled devices are created. Some of these new devices will render documents in different ways than we’re currently accustomed to. On the other hand, it is possible to create style sheets that are very exacting when it comes to how XML data is displayed. For example, using XSL-FO you can specify the exact dimensions of a printed page, including margin sizes and the specific location of XML content on the page. The degree to which you have control over the appearance of styled XML content largely has to do with whether the content is being rendered in a web browser or in some other medium, such as print.

The concept of different devices rendering XML documents in different ways has been referred to as cross-medium rendering due to the fact that the devices typically represent different mediums. Historically, HTML has had to contend with cross-browser rendering, which was caused by different browsers supporting different presentation tags. Even though style sheets alleviate the cross-browser problem, they don’t always deal with the cross-medium problem. To understand what I mean by this, consider CSS style sheets, which provide a means of applying layout rules to XML so that it can be displayed. The relatively simplistic styling approach taken by CSS isn’t powerful enough to deal with the cross-medium issue because it can’t transform an XML document into a different format, which is often required to successfully render a document in a different medium.

XSLT addresses the need for transforming XML documents according to a set of highly structured patterns. For display purposes, you can use XSLT to translate an XML document into an HTML document. This is the primary way XML developers are currently using XSL because it doesn’t require anything more on the part of browsers than support for XSLT; they don’t have to be able to render a document directly from XML. CSS doesn’t involve any transformation; it simply provides a means of describing how different parts of a document should be displayed.

By the Way

Some people incorrectly perceive XSL and CSS as competing technologies, but they really aren’t. In fact, it can be very advantageous to use XSLT and CSS together. Competition primarily enters the picture with XSL-FO, which indeed does everything that CSS can do, and much more. Even so, the popularity of CSS as a style sheet technology for web pages will likely prevent XSL-FO from seriously encroaching on it in the near term. For now, we’ll likely see CSS continue to be used as the dominant style sheet technology for web-based XML formatting, while XSL-FO will continue to rise in importance for print-based XML formatting.

You’ve already spent some time learning about the differences between CSS and XSL, but it’s worth going through a more detailed comparison so that you have a solid understanding of your style sheet options. More importantly, I want to point out some of the issues for choosing one style sheet technology over the other, especially when working with documents in a web environment. The technologies are just similar enough that it can be difficult determining when to use which one. You may find that the best approach to styling XML documents is a hybrid approach involving both XSL and CSS.

There are several key differences between CSS, XSLT, and XSL-FO, which I’ve alluded to earlier in the hour:

CSS allows you to style HTML documents (XSLT cannot, and XSL-FO cannot unless the documents are valid XHTML documents)

XSL-FO allows you to style XML documents via an XML syntax (CSS and XSLT cannot), although web support is lacking

XSLT allows you to transform XML documents (CSS and XSL-FO cannot)

You’re here to learn about XML, not HTML, so the first difference between CSS and XSLT/XSL-FO might not seem to matter much. However, when you consider the fact that many XML applications currently involve HTML documents to some degree, this may be an issue when assessing the appropriate style sheet technology for a given project. And more importantly, you have to consider the fact that XSL-FO has yet to garner browser support, which means that it isn’t a viable option for formatting data to be displayed on the Web.

The third difference is critical in that CSS provides no direct means of transforming XML documents. You can use a scripting language with the DOM to transform XML documents, but that’s another issue that requires considerable knowledge of XML scripting, which you gain in Part IV. Unlike scripting languages, CSS was explicitly designed for use by nonprogrammers, which explains why it is so easy to learn and use. CSS simply attaches style properties to elements in an XML/HTML document. The simplicity of CSS comes with limitations, some of which follow:

CSS cannot reuse document data

CSS cannot conditionally select document data (other than hiding specific types of elements)

CSS cannot calculate quantities or store values in variables

CSS cannot generate dynamic text, such as page numbers

These limitations of CSS are important because they are noticeably missing in XSLT. In other words, XSLT is capable of carrying out these tasks and therefore doesn’t suffer from the same weaknesses. If you don’t mind a steeper learning curve, the XSLT capabilities for searching and rearranging document content are far superior to both CSS and XSL-FO. Of course, XSLT doesn’t directly support formatting styles in the way that CSS and XSL-FO do, so you may find that using XSLT by itself still falls short in some regards. This may lead you to consider pairing XSLT with CSS or XSL-FO for the ultimate flexibility in styling XML documents. Following are a couple of ways that XSLT and CSS/XSL-FO can be used together to provide a hybrid XML style sheet solution:

Use XSLT to transform XML documents into HTML documents that are styled with CSS style sheets.

Use XSLT to transform XML documents into XML documents that are styled with CSS or XSL-FO style sheets.

The first approach represents the most straightforward combination of XSLT and CSS because its results are in HTML form, which is more easily understood by web browsers. In fact, a web browser doesn’t even know that XML is involved when using this approach; all that the browser sees is a regular HTML document that is the result of an XSLT transformation on the server. The second approach is interesting because it involves styling XML code directly in browsers. This means that it isn’t necessary to first transform XML documents into HTML/XHTML documents; the only transformation that takes place in this case is the transformation from one XML document into another XML document that is better suited for presentation.

By the Way

The emphasis for now needs to be on styling XML documents for the Web using CSS as opposed to XSL-FO because CSS is much more widely supported in browsers. However, this may change as web developers continue to inject more XML into their web sites, which could lead browser vendors to eventually offer better support for XSL-FO.

Every style sheet regardless of its type is a text file. CSS style sheets adhere to their own text format, whereas XSLT and XSL-FO style sheets are considered XML documents. CSS style sheets are always given a file extension of .css. XSLT and XSL-FO style sheets are a little different in that they can use one of several file extensions. First of all, it’s completely legal to use the general .xml file extension for both XSLT and XSL-FO style sheets. However, if you want to get more specific you can use the .xsl file extension for either type of style sheet. Or if you want to take things a step further, you can use the .xslt file extension for XSLT style sheets and .fo file extension for XSL-FO style sheets. The bottom line is that the type of the file is determined only when the content is processed, so the file extension is more for your purposes in quickly identifying the types of files.

By the Way

The XSLT example later in this lesson uses the .xsl file extension to reference an XSLT style sheet.

The next few hours spend plenty of time exploring the inner workings of CSS and XSL, but I hate for you to leave this hour without seeing a practical example of the technologies in action. Earlier in the book I used an XML document (talltales.xml) that contained questions and answers for a trivia game called Tall Tales as an example. I’d like to revisit that document, as it presents a perfect opportunity to demonstrate the basic usage of CSS and XSLT style sheets. Listing 9.1 is the Tall Tales trivia document.

By the Way

If you’re wondering why I don’t provide an example of an XSL-FO style sheet here, it’s because I want you to be able to immediately see the results in a web browser. As you learn in Hour 14, “Formatting XML with XSL-FO,” XSL-FO requires the assistance of a special processor application known as a FOP (XSL-FO Processor).

Example 9.1. The Tall Tales Example XML Document

1: <?xml version="1.0"?>

2:

3: <talltales>

4: <tt answer="a">

5: <question>

6: In 1994, a man had an accident while robbing a pizza restaurant in

7: Akron, Ohio, that resulted in his arrest. What happened to him?

8: </question>

9: <a>He slipped on a patch of grease on the floor and knocked himself

out.</a>

10: <b>He backed into a police car while attempting to drive off.</b>

11: <c>He choked on a breadstick that he had grabbed as he was running

out.</c>

12: </tt>

13:

14: <tt answer="c">

15: <question>

16: In 1993, a man was charged with burglary in Martinsville, Indiana,

17: after the homeowners discovered his presence. How were the homeowners

18: alerted to his presence?

19: </question>

20: <a>He had rung the doorbell before entering.</a>

21: <b>He had rattled some pots and pans while making himself a waffle in

22: their kitchen.</b>

23: <c>He was playing their piano.</c>

24: </tt>

25:

26: <tt answer="a">

27: <question>

28: In 1994, the Nestle UK food company was fined for injuries suffered

29: by a 36 year-old employee at a plant in York, England. What happened

30: to the man?

31: </question>

32: <a>He fell in a giant mixing bowl and was whipped for over a minute.</a>

33: <b>He developed an ulcer while working as a candy bar tester.</b>

34: <c>He was hit in the head with a large piece of flying chocolate.</c>

35: </tt>

36: </talltales>Nothing is too tricky here; it’s just XML code for questions and answers in a quirky trivia game. Notice that each question/answer set is enclosed within a tt element—this will be important in a moment when you see the CSS and XSLT style sheets used to transform the document.

By the Way

It’s worth pointing out that there are slightly different versions of the XML document required for each style sheet. This is because an XML document must reference the appropriate style sheet that is used to format its content.

The CSS solution to styling any XML document is simply to provide style rules for the different elements in the document. These style rules are applied to all of the elements in a document in order to provide a visualization of the document. In the case of the Tall Tales document, there are really only five elements of interest: tt, question, a, b, and c. Listing 9.2 is the CSS style sheet (talltales.css) that defines style rules for these elements.

Example 9.2. The talltales.css CSS Style Sheet for Formatting the Tall Tales XML Document

1: talltales {

2: background-image: url(background.gif);

3: background-repeat: repeat;

4: }

5:

6: tt {

7: display: block;

8: width: 700px;

9: padding: 10px;

10: margin: 10px;

11: border: 5px groove #353A54;

12: background-color: #353A54;

13: }

14:

15: question {

16: display: block;

17: color: #F4EECA;

18: font-family: Verdana, Arial;

19: font-size: 13pt;

20: text-align: left;

21: }

22:

23: a, b, c {

24: display: block;

25: color: #6388A0;

26: font-family: Verdana, Arial;

27: font-size: 12pt;

28: text-indent: 14px;

29: text-align: left;

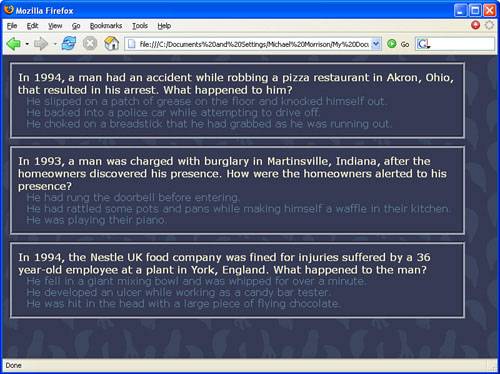

30: }Before we go any further, understand that I don’t expect you to understand the inner workings of this CSS code. You don’t formally learn about CSS style rules until the next hour—right now I just wanted to hit you with a practical example so you could at least see what a CSS style sheet looks like. If you already have experience with CSS by way of HTML, this style sheet should be pretty easy to understand. If not, you can hopefully study it and at least take in the high points. For example, it’s not too hard to figure out that colors and fonts are being set for each of the elements. Figure 9.1 shows the result of using this style sheet to display the Tall Tales XML document in Firefox.

By the Way

As with all the examples throughout the book, the complete code for the Tall Tales example is available from my web site at http://www.michaelmorrison.com/. The version of the Tall Tales XML document that is styled via CSS is titled talltales_css.xml.

Although you can’t quite make out the colors in this figure, it’s apparent from the style sheet code that colors are being used to display the elements. Now it’s time to take a look at how XSLT can be used to arrive at the same visual result.

The XSLT approach to the Tall Tales document involves translating the document into HTML. Although it’s possible to simply translate the document into HTML and let HTML do the job of determining how the data is displayed, a better idea is to use inline CSS styles to format the data directly within the HTML code. Keep in mind that when you translate an XML document into HTML using XSLT, you can include anything that you would otherwise include in an HTML document, including inline CSS styles. Listing 9.3 shows the XSLT style sheet (talltales.xslt) for use with the Tall Tales document.

Example 9.3. The talltales.xsl XSLT Style Sheet for Transforming the Tall Tales XML Document into HTML

1: <?xml version="1.0"?>

2: <xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

3: xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

4: xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

5: <xsl:template match="/">

6: <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

7: <head>

8: </head>

9: <body style="background-image: url(background.gif); background-repeat:

repeat">

10: <xsl:for-each select="talltales/tt">

11: <div style="width:700px; padding:10px; margin: 10px;

12: border:5px groove #353A54; background-color:#353A54">

13: <xsl:apply-templates select="question"/>

14: <xsl:apply-templates select="a"/>

15: <xsl:apply-templates select="b"/>

16: <xsl:apply-templates select="c"/>

17: </div>

18: </xsl:for-each>

19: </body>

20: </html>

21: </xsl:template>

22:

23: <xsl:template match="question">

24: <div style="color:#F4EECA; font-family:Verdana,Arial; font-size:13pt">

25: <xsl:value-of select="."/>

26: </div>

27: </xsl:template>

28:

29: <xsl:template match="a|b|c">

30: <div style="color:#6388A0; font-family:Verdana,Arial; font-size:12pt;

text-indent:14px">

31: <xsl:value-of select="."/>

32: </div>

33: </xsl:template>

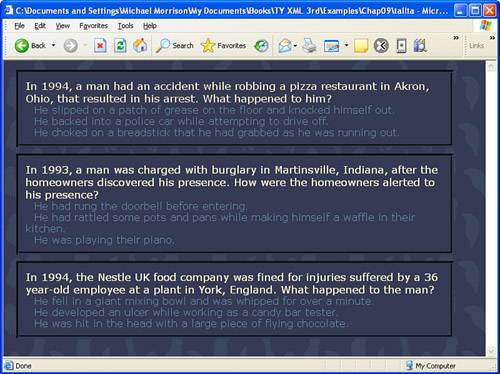

34: </xsl:stylesheet>Notice that this style sheet is considerably more complex than its CSS counterpart. This has to do with the fact that this style sheet is actually constructing an HTML document on the fly. In other words, the XSLT code is describing how to build an HTML document out of XML data, complete with inline CSS styles. Again, you could accomplish a similar feat without the CSS styles, but you wouldn’t be able to make the resulting page look exactly like the result of the CSS style sheet. This is because XSLT isn’t in the business of controlling font sizes and colors; XSLT is all about transforming data. Figure 9.2 shows the result of viewing the Tall Tales document in Internet Explorer using the XSLT style sheet.

Figure 9.2. The Tall Tales example document is displayed in Internet Explorer using an XSLT style sheet.

By the Way

The version of the Tall Tales XML document that is styled via XSLT is titled talltales_xslt.xml, and is available for download as part of the complete example code for this book at my web site (http://www.michaelmorrison.com/).

If you look back to Figure 9.1, you’ll be hard pressed to tell the difference between it and this figure. In fact, the only noticeable difference is the file name of the document in the title bar of the web browser. This reveals how it is often possible to accomplish similar tasks using either CSS or XSLT. Obviously, CSS is superior for styling simple XML documents due to the simplicity of CSS style sheets. However, any time you need to massage the data in an XML document before displaying it, you’ll have to go with XSLT.

Style sheets represent an important technological innovation with respect to the Web because they make it possible to exert exacting control over the appearance of content in both HTML and XML documents. Style sheets allow markup languages such as HTML and other custom XML-based languages to focus on their primary job—structuring data according to its meaning. With a clean separation between content and presentation, documents coded in HTML and XML are better organized and more easily managed.

This hour introduced you to the basics of style sheets, including the three main style sheet technologies that are applicable to XML: CSS, XSLT, and XSL-FO. Although these technologies all solve similar problems, they are very different technologies with unique pros and cons. Although you learned the fundamentals of how and when to use each type of style sheet, the remaining hours in this part of the book paint a much clearer picture of what can be done in the way of styling XML data with CSS, XSLT, and XSL-FO style sheets.

Why is it so important to separate the presentation of a document from its content? | |

It’s been proven time and again that mixing data with its presentation severely hampers the structure and organization of the data because it becomes very difficult to draw a line between what is content and what is presentation. For example, it is currently difficult for search engines to extract meaningful information about web pages because most HTML documents are concerned solely with how information is to be displayed. If those documents were coded according to meaning, as opposed to worrying so much about presentation, the Web and its search engines would be much smarter. Of course, we all care about how information looks, especially on the Web, so no one ever said to do away with presentation. The idea is to make a clean separation between content and presentation so that both of them can be more easily managed. A good example of how this concept is being applied to a very practical web service is Yahoo!’s Flickr online photo service (http://www.flickr.com/), which allows you to associate keywords with photographs that you post online. As more and more people add context to their photographs via keywords, it will be increasingly possible to search the Web for the content of photographs, which is something previously impossible. With photographs, the content is inherently linked with the presentation but keywords allow you to tack on additional information about the content. | |

What does it mean to state that XSL-FO is a superset of CSS? | |

When I say that XSL-FO is a superset of CSS, I mean that XSL-FO encompasses the functionality of CSS and also goes far beyond CSS. In other words, XSL-FO is designed to support the features of CSS along with many new features of its own. The idea behind this approach is to provide a smooth migration path between CSS and XSL-FO because XSL-FO inherently supports CSS features. |

The Workshop is designed to help you anticipate possible questions, review what you’ve learned, and begin learning how to put your knowledge into practice.