Someone told me that each equation I included in the book would halve the sales. | ||

| --Stephen Hawking (on his book A Brief History of Time) | ||

Unlike Mr. Hawking, I’m not afraid of a little extra complexity hurting the sales of this book. In fact, it’s necessary because XSL is a more complex style sheet technology than CSS, so there is no way to thoroughly cover style sheets without things getting a little messy. Fortunately, as you learn in this hour, XSL is a technology that has considerably more to offer than CSS. XSL is designed to do a whole lot more than just format XML content for display purposes; it gives you the ability to completely transform XML documents. You learn in this hour how to transform XML documents into HTML documents that can be viewed in web browsers. Additionally, you should realize that the extra complexity in XSL is quite worth the learning curve because of its immense power and flexibility.

In this hour, you’ll learn

The basics of XSL and the technologies that comprise it

The building blocks of the XSL Transformation (XSLT) language

How to wire an XSL style sheet to an XML document

How to develop an XSLT style sheet

As you’ve learned in previous hours, style sheets are special documents or pieces of code that are used to format XML content for display purposes. This definition of a style sheet is perfectly accurate for CSS, which is a style sheet technology that originated as a means of adding tighter control of HTML content formatting. XSL is also a style sheet technology, but it reaches beyond the simple formatting of content by also allowing you to completely transform content. Unlike CSS, XSL was solely designed as a style sheet technology for XML. In many ways, XSL accomplishes the same things that can be accomplished using CSS. However, XSL goes much further than CSS in its support for manipulating the structure of XML documents.

As you might expect, XSL is implemented using XML, which means that you code XSL style sheets using XML code. Even so, you may find it necessary to still use CSS in conjunction with XSL, at least in the near future. The reason for this has to do with the current state of XSL support in web browsers. The component of XSL currently supported in web browsers is XSLT, which allows you to transform XML documents via style sheet code. XSLT doesn’t directly support the formatting of XML content for display purposes. The formatting component of XSL is XSL Formatting Objects, or XSL-FO, which consists of special style objects that can be applied to XML content to format it for display. Support for XSL-FO is currently weak in major web browsers, which doesn’t make XSL-FO a viable alternative for the Web at the moment. In the meantime, XSLT is quite useful when paired with CSS; XSLT allows you to transform any XML document into HTML that can be styled and displayed with CSS in a web browser.

By the Way

Although XSL-FO isn’t currently a good option for styling XML documents for web browsers, it is quite effective at styling XML documents for printing. For example, you can use XSL-FO to convert an XML document into an Adobe Acrobat PDF document that has a very exacting layout. You learn how to carry out this exact task in Hour 14, “Formatting XML with XSL-FO.”

It is important to understand how an XSL style sheet is processed and applied to an XML document. This task begins with an XML processor, which is responsible for reading an XML document and processing it into meaningful pieces of information known as nodes. More specifically, you learned earlier in the book that XML documents are processed into a hierarchical tree containing nodes for each piece of information in a document. For example, every element and attribute in a document represents a node in the tree representation of a document. Thinking of an XML document as a tree is extremely important when it comes to understanding XSL. After a document has been processed into a tree, a special processor known as an XSL processor begins applying the rules of an XSL style sheet to the document tree.

The XSL processor starts with the root node (root element) in the tree and uses it as the basis for performing pattern matching in the style sheet. Pattern matching is the process of using patterns to identify nodes in the tree that are to be processed according to XSL styles. These patterns are stored within constructs known as templates in XSL style sheets. The XSL processor analyzes templates and the patterns associated with them to process different parts of the document tree. When a match is made, the portion of the tree matching the given pattern is processed by the appropriate style sheet template. At this point, the rules of the template are applied to the content to generate a result tree. The result tree is itself a tree of data, but the data in this case has somehow been transformed by the style sheet. To put it another way, the XSL processor takes a document tree as input and generates another tree, a result tree, as output. Figure 11.1 illustrates the process of using a pattern to match a portion of a document tree and then applying a pattern to it to generate a result tree.

Figure 11.1. A pattern is used to match a portion of a document, which is then transformed into a result tree using a template.

By the Way

When I refer to a “tree” of data, I’m really talking about the logical structure of the data. To better understand what I mean, think in terms of your family tree, where each relationship forms a branch and each person forms a leaf, or node, on the tree. The same logical relationships apply to XML trees, except the nodes are elements and attributes as opposed to people.

The result tree may contain XML code, HTML code, or special objects known as XSL formatting objects. In the case of XML code, the result tree represents a transformation from one form of XML to another. In the case of HTML code, the result tree represents a transformation from XML code into HTML code that can be viewed in a web browser. Technically speaking, you can’t use traditional HTML code as the basis for an XSL result tree because traditional HTML isn’t considered an XML-based language. However, if the HTML code adheres to XHTML standards, which is a stricter version of HTML formulated as an XML language, everything will work fine. You learn more about XHTML in Hour 21, “Adding Structure to the Web with XHTML.” You also learn how to transform XML code into HTML (XHTML) later in this hour in the section titled, “Your First XSLT Style Sheet.”

In order to finish creating the result tree, the XSL processor continues processing each node in the document tree, applying all the templates defined in the style sheet. When all the nodes have been processed and all the style sheet templates applied, the XSL processor returns the completed result tree, which is often in a format suitable for display. I say “often” because it is possible to use XSL to transform a from one XML language to another instead of to XHTML, in which case the resulting document may or may not be used for display purposes.

In order to understand the relevance of XSL technologies, it’s important to examine the role of the XSL processor once more. The XSL processor is responsible for performing two fundamental tasks:

Construct a result tree from a transformation of a source document tree

Interpret the result tree for formatting purposes

The first task addressed by the XSL processor is known as tree transformation and involves transforming a source tree of document content into a result tree. Tree transformation is basically the process of transforming XML content from one XML language into another and involves the use of XSLT. The second task performed by the XSL processor involves examining the result tree for formatting information and formatting the content for each node accordingly. This task requires the use of XSL-FO and is currently not supported very well in web browsers. Even so, it is a critical part of XSL that will likely play a significant role in the future of XML.

Although it certainly seems convenient to break up XSL processing into two tasks, there is a much more important reason for doing so than mere convenience. One way to understand this significance is to consider CSS, which supports only the formatting of XML content. The limitations of CSS are obvious when you consider that a source document can’t really be modified in any way for display purposes. On the other hand, with XSL you have complete freedom to massage the source document at will during the transformation part of the document processing. The one-two punch of transformation followed by formatting provides an incredible degree of flexibility for rendering XML documents for display.

The two fundamental tasks taken on by the XML processor directly correspond to two XSL technologies: XSLT and XSL-FO. Additionally, there is a third XSL technology, XPath, which factors heavily into XSLT. XSLT and XSL-FO are both implemented as XML languages, which makes their syntax familiar. This also means that style sheets created from them are XML documents. The interesting thing about these two components of XSL is that they can be used together or separately. You can use XSLT to transform documents without any concern over how the documents are formatted. Similarly, you can use XSL Formatting Objects to format XML documents without necessarily performing any transformation on them.

By the Way

Keep in mind that while web browsers have been slow to adopt XSL-FO, there are plenty of tools available for formatting XML code using XSL-FO. Later in the book in Hour 14 you find out how to use one of these tools to convert an XML document into a PDF document via XSL-FO.

The important thing to keep in mind regarding the structure of XSL is the fact that XSL is really three languages, not one. XSLT is the XSL transformation language that is used to transform XML documents from one vocabulary to another. XSL-FO is the XSL formatting language that is used to apply formatting styles to XML documents for presentation purposes. And finally, XPath is a special non-XML expression language used to address parts of an XML document.

By the Way

Although you learn the basics of XPath in this hour and the next, you aren’t formally introduced to it until Hour 22, “Addressing and Linking XML Documents.” In that hour you learn the details of how to address portions of an XML document using XPath.

XSL Transformation (XSLT) is the transformation component of the XSL style sheet technology. XSLT consists of an XML-based markup language that is used to create style sheets for transforming XML documents. These style sheets operate on parsed XML data in a tree form, which is then output as a result tree consisting of the transformed data. XSLT uses a powerful pattern-matching mechanism to select portions of an XML document for transformation. When a pattern is matched for a portion of a tree, a template is used to determine how that portion of the tree is transformed. You learn more about how templates and patterns are used to transform XML documents a little later in this lesson.

An integral part of XSLT is a technology known as XPath, which is used to select nodes for processing and generating text. The next section examines XPath in more detail. The remainder of this hour and the next tackles XSLT in greater detail.

XPath is a non-XML expression language that is used to address parts of an XML document. XPath is different from its other XSL counterparts (XSLT and XSL-FO) in that it isn’t implemented as an XML language. This is due to the fact that XPath expressions are used in situations where XML markup isn’t really applicable, such as within attribute values. As you know, attribute values are simple text and therefore can’t contain additional XML markup. So, although XPath expressions are used within XML markup, they don’t directly use familiar XML tags and attributes themselves.

The central function of XPath is to provide an abstract means of addressing XML document parts—for this reason, XPath forms the basis for document addressing in XSLT. The syntax used by XPath is designed for use in URIs and XML attribute values, which requires it to be extremely concise. The name XPath is based on the notion of using a path notation to address XML documents, much as you might use a path in a file system to describe the location of a file. Similar to XSLT, XPath operates under the assumption that a document has been parsed into a tree of nodes. XPath defines different node types that are used to describe the nodes that appear within a tree. There is always a single root node that serves as the root of an XPath tree, and that appears as the first node in the tree. Every element in a document has a corresponding element node that appears in the tree under the root node. Within an element node there are other types of nodes that correspond to the element’s content. Element nodes may have a unique identifier associated with them, which is used to reference the node with XPath.

Following is an example of a simple XPath expression, which demonstrates how XPath expressions are used in attribute values:

<xsl:for-each select="contacts/contact">

This code shows how an XPath expression is used within an XSLT element (xsl:for-each) to reference elements named contact that are children of an element named contacts. Although it isn’t important for you to understand the implications of this code in an XSLT style sheet, it is important to realize that XPath is used to address certain nodes (elements) within a document.

When an XPath expression is used in an XSLT style sheet, the evaluation of the expression results in a data object of a specific type, such as a Boolean (true/false) or a number. The manner in which an XPath expression is evaluated is entirely dependent upon the context of the expression, which isn’t determined by XPath. The context of an XPath expression is determined by XSLT, which in turn determines how expressions are evaluated. This is the abstract nature of XPath that allows it to be used as a helper technology alongside XSLT to address parts of documents.

By the Way

XPath’s role in XSL doesn’t end with XSLT—XPath is also used with XLink and XPointer, which you learn about in Hour 22.

XSL Formatting Objects (XSL-FO) represents the formatting component of the XSL style sheet technology and is designed to be a functional superset of CSS. This means that XSL-FO contains all of the functionality of CSS, even though it uses its own XML-based syntax. Similar to XSLT, XSL-FO is implemented as an XML language, which is beneficial for both minimizing the learning curve for XML developers and easing its integration into existing XML tools. Also like XSLT, XSL-FO operates on a tree of XML data, which can either be parsed directly from a document or transformed from a document using XSLT. For formatting purposes, XSL-FO treats every node in the tree as a formatting object, with each node supporting a wide range of presentation styles. You can apply styles by setting attributes on a given element (node) in the tree.

There are formatting objects that correspond to different aspects of document formatting such as layout, pagination, and content styling. Every formatting object has properties that are used to somehow describe the object. Some properties directly specify a formatted result, such as a color or font, whereas other properties establish constraints on a set of possible formatted results. Following is perhaps the simplest possible example of XSL-FO, which sets the font family and font size for a block of text:

<fo:block font-family="Arial" font-size="16pt"> This text has been styled with XSL-FO! </fo:block>

As you can see, this code performs a similar function to CSS in establishing the font family and font size of a block of text. XSL-FO actually goes further than CSS in allowing you to control the formatting of XML content in extreme detail. The layout model employed by XSL-FO is described in terms of rectangular areas and spaces, which isn’t too surprising considering that this approach is employed by most desktop publishing applications. Rectangular areas in XSL-FO are not objects themselves, however; it is up to formatting objects to establish rectangular areas and the relationships between them. This is somewhat similar to rectangular areas in CSS, where you establish the size of an area (box) by setting the width and height of a paragraph of text. XSL-FO also offers a very high degree of control over print-specific page attributes such as page margins.

The XSL processor is heavily involved in carrying out the functionality in XSL-FO style sheets. When the XSL processor processes a formatting object within a style sheet, the object is mapped into a rectangular area on the display surface. The properties of the object determine how it is formatted, along with the parameters of the area into which it is mapped.

By the Way

The immediate downside to XSL-FO is that there is little support for it in major web browsers. For this reason, coverage of XSL-FO in this book focuses solely on formatting XML data for print purposes (Hour 14).

Seeing as how XSL-FO is extremely limited in current major web browsers, the practical usage of XSL with respect to the Web must focus on XSLT for the time being. This isn’t entirely a bad thing when you consider the learning curve for XSL in general. It may be that by staggering the adoption of the two technologies, the W3C may be inadvertently giving developers time to get up to speed with XSLT before tackling XSL-FO. The remainder of this hour focuses on XSLT and how you can use it to transform XML documents.

As you now know, the purpose of an XSLT style sheet is to process the nodes of an XML document and apply a pattern-matching mechanism to determine which nodes are to be transformed. Both the pattern-matching mechanism and the details of each transformation are spelled out in an XSLT style sheet. More specifically, an XSLT style sheet consists of one or more templates that describe patterns and expressions, which are used to match XML content for transformation purposes. The three fundamental constructs in an XSL style sheet are as follows:

Templates

Patterns

Expressions

Before getting into these constructs, however, you need to learn about the xsl:stylesheet element and learn how the XSLT namespace is used in XSLT style sheets. The stylesheet element is the document (root) element for XSL style sheets and is part of the XSLT namespace. You are required to declare the XSLT namespace in order to use XSLT elements and attributes. Following is an example of declaring the XSLT namespace inside of the stylesheet element:

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

This example namespace declaration sets the prefix for the XSLT namespace to xsl, which is the standard prefix used in XSL style sheets. You must precede all XSLT elements and attributes with this prefix. Notice in the code that the XSLT namespace is http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform. Another important aspect of this code is the version attribute, which sets the version of XSL used in the style sheet. Currently the only version of XSL is 1.0, so you should set the version attribute to 1.0 in your style sheets.

By the Way

The XSLT namespace is specific to XSLT and does not apply to all of XSL. If you plan on developing style sheets that use XSL-FO, you’ll also need to declare the XSL-FO namespace, which is http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format and typically has the prefix fo. Furthermore, if you plan on using XSLT to transform web pages, it’s a good idea to declare the XHTML namespace: http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml.

A template is an XSL construct that describes output to be generated based upon certain pattern-matching criteria. The idea behind a template is to define a transformation mechanism that applies to a certain portion of an XML document, which is a node or group of nodes. Although it is possible to create style sheets consisting of a single template, you will more than likely create multiple templates to transform different portions of the XML document tree.

Templates are defined in XSL style sheets using the xsl:template element, which is primarily a container element for patterns, expressions, and transformation logic. The xsl:template element uses an optional attribute named match to match patterns and expressions in an XSLT style sheet. You can think of the match attribute as specifying a portion of the XML tree for a document. The widest possible match for a document is to set the match attribute to /, which indicates that the root of the tree is to be matched. This results in the entire tree being selected for transformation by the template, as the following code demonstrates:

<xsl:template match="/"> ... </xsl:template>

If you have any experience with databases, you might recognize the match attribute as being somewhat similar to a query in a database language. To understand what I mean by this, consider the following example, which uses the match attribute to match only elements named state:

<xsl:template match="state"> ... </xsl:template>

This template would come in useful for XML documents that have elements named state. For example, the template would match the state element in the following XML code:

<contact> <name>Frank Rizzo</name> <address>1212 W 304th Street</address> <city>New York</city> <state>New York</state> <zip>10011</zip> </contact>

Matching a portion of an XML document wouldn’t mean much if the template didn’t carry out any kind of transformation. Transformation logic is created using several template constructs that are used to control the application of templates in XSL style sheets. These template constructs are actually elements defined in the XSLT namespace. Following are some of the more commonly used XSLT elements:

A crucial part of XSLT document transformation is the insertion of document content into the result tree, which is carried out with the xsl:value-of element. The xsl:value-of element provides the mechanism for transforming XML documents because it allows you to output XML data in virtually any context, such as within HTML markup. The xsl:value-of element requires an attribute named select that identifies the specific content to be inserted. Following is an example of a simple template that uses the xsl:value-of element and the select attribute to output the value of an element named title:

<xsl:template match="title"> <xsl:value-of select="."/> </xsl:template>

In this example, the select attribute is set to ., which indicates that the current node is to be inserted into the result tree. The value of the select attribute works very much like the path of a file on a hard drive. For example, a file on a hard drive might be specified as docsletterslovenote.txt. This path indicates the folder hierarchy of the file lovenote.txt. In a similar way, the select attribute specifies the location of the node to be inserted in the result tree. A dot (.) indicates a node in the current context, as determined by the match attribute. An element or attribute name indicates a node beneath the current node, whereas two dots (..) indicate the parent of the current node. This approach to specifying node paths using a special expression language is covered in much greater detail in Hour 22.

To get an idea as to how the previous example template (matching title elements) can be used to transform XML code, take a look at the following code excerpt:

<book> <title>All The King's Men</title> <author>Robert Penn Warren</author> </book> <book> <title>Atlas Shrugged</title> <author>Ayn Rand</author> </book> <book> <title>Ain't Nobody's Business If You Do</title> <author>Peter McWilliams</author> </book>

Applying the previous template to this code would result in the following results:

All The King's Men Atlas Shrugged Ain't Nobody's Business If You Do

As you can see, the titles of the books are plucked out of the code because the template matched title elements and then inserted their contents into the resulting document.

In addition to inserting XML content using the xsl:value-of element in a style sheet, it is also possible to conditionally carry out portions of the logic in a style sheet. More specifically, the xsl:if element is used to perform conditional matches in templates. This element uses the same match attribute as the xsl:template element to establish conditional branching in templates. Following is an example of how the xsl:if element is used to test if the name of a state attribute is equal to TN:

<xsl:if match="@state=TN"> <xsl:apply-templates select="location"/> </xsl:if>

This code might be used as part of an online mapping application. Notice in the code that the state attribute is preceded by an “at” symbol (@); this symbol is used in XPath to identify an attribute, as opposed to an element. Another important aspect of this code is the manner in which the location template is applied only if the state attribute is equal to TN. The end result is that only the location elements whose state attribute is set to TN are processed for transformation.

If you have any programming experience, you are no doubt familiar with loops, which allow you to repeatedly perform an operation on a number of items. If you don’t have programming experience, understand that a loop is a way of performing an action over and over. In the case of XSLT, loops are created with the xsl:for-each element, which is used to loop through elements in a document. The xsl:for-each element requires a select attribute that determines which elements are selected as part of the loop’s iteration. Following is an example of using the xsl:for-each element to iterate through a list of locations:

<xsl:for-each select="locations/location"> <h1><xsl:value-of select="@city"/>, <xsl:value-of select="@state"/></h1> <h2><xsl:value-of select="description"/></h2> </xsl:for-each>

In this example, the xsl:for-each element is used to loop through location elements that are stored within the parent locations element. Within the loop, the city and state attributes are inserted into the result tree, along with the description element. This template is interesting in that it uses carefully placed HTML elements to transform the XML code into HTML code that can be viewed in a web browser. Following is some example code to which you might apply this template:

</locations>

<location city="Washington" state="DC">

<description>The United States Capital</description>

</location>

<location city="Nashville" state="TN">

<description>Music City USA</description>

</location>

<location city="Chicago" state="IL">

<description>The Windy City</description>

</location>

</locations>Applying the previous template to this code yields the following results:

<h1>Washington, DC</h1> <h2>The United States Capital</h2> <h1>Nashville, TN</h1> <h2>Music City USA</h2> <h1>Chicago, IL</h1> <h2>The Windy City</h2>

As you can see, the template successfully transforms the XML code into XHTML code that is capable of being viewed in a web browser. Notice that the cities and states are combined within large heading elements (h1), followed by the descriptions, which are coded in smaller heading elements (h2).

In order for a template to be applied to XML content, you must explicitly apply the template with the xsl:apply-templates element. The xsl:apply-templates element supports the familiar select attribute, which performs a similar role to the one it does in the xsl:for-each element. When the XSL processor encounters an xsl:apply-templates element in a style sheet, the template corresponding to the pattern or expression in the select attribute is applied, which means that relevant document data is fed into the template and transformed. Following is an example of applying a template using the xsl:apply-templates element:

<xsl:apply-templates select="location"/>

By the Way

The exception to the rule of having to use the xsl:apply-templates element to apply templates in an XSLT style sheet is the root element, whose template is automatically applied if one exists.

This code results in the template for the location element being invoked in the current context.

Patterns and expressions are used in XSLT templates to perform matches and are ultimately responsible for determining what portions of an XML document are passed through a particular template for transformation. A pattern describes a branch of an XML tree, which in turn consists of a set of hierarchical nodes. Patterns are used throughout XSL to describe portions of a document tree for applying templates. Patterns can be constructed to perform relatively complex pattern-matching tasks. When you think of patterns in this light, they form somewhat of a mini-query language that can be used to provide exacting controls over the portions of an XML document that are selected for transformation in templates.

As you learned earlier, the syntax used by XSL patterns is somewhat similar to that used when specifying paths to files on a disk drive. For example, the contacts/contact/phone pattern selects phone elements that are children of a contact element, which itself is a child of a contacts element. It is possible, and often useful, to select the entire document tree in a pattern, which is carried out with a single forward slash (/). This pattern is also known as the root pattern and is assumed in other patterns if you leave it off. For example, the contacts/contact/phone pattern is assumed to begin at the root of the document, which means that contacts is the root element for the document.

Expressions are similar to patterns in that they also impact which nodes are selected for transformation. However, expressions are capable of carrying out processing of their own, such as mathematical calculations, text processing, and conditional tests. XSL includes numerous built-in functions that are used to construct expressions within style sheets. Following is a simple example of an expression:

<xsl:value-of select="sum(@price)"/>

This code demonstrates how to use the standard sum() function to calculate the sum of the price attributes within a particular set of elements. This could be useful in a shopping cart application that needs to calculate a subtotal of the items located in the cart.

Admittedly, this discussion isn’t the last word on XSL patterns and expressions. Fortunately, you learn a great deal more about patterns and expressions in Hour 22. In the meantime, this introduction will get you started creating XSL style sheets.

In Hour 10, “Styling XML Content with CSS,” you learned how to create and connect CSS style sheets to XML documents. These types of style sheets are known as external style sheets because they are stored in separate, external files. XSL style sheets are also typically stored in external files, in which case you must wire them to XML documents in order for them to be applied. XSL style sheets are typically stored in files with a .xsl filename extension and are wired to XML documents using the xml-stylesheet processing instruction. The xml-stylesheet processing instruction includes a couple of attributes that determine the type and location of the style sheet:

By the Way

You can also use the general file extension .xml or the more specific extension .xslt for your XSLT style sheets. The extension really doesn’t matter so long as you reference the style sheet properly from the XML document to which it applies.

type— The type of the style sheet (text/xsl, for example)href— The location of the style sheet

By the Way

You may notice that this discussion focuses on XSL style sheets in general, as opposed to XSLT style sheets. That’s because XSLT style sheets are really just a specific kind of XSL style sheet, and from the perspective of an XML document there is no difference between the two. So, when it comes to associating an XSLT style sheet with an XML document, you simply reference it as an XSL style sheet.

These two attributes should be somewhat familiar to you from the discussion of CSS because they are also used to wire CSS to XML documents. The difference in their usage with XSL is revealed in their values—the type attribute must be set to text/xsl for XSL style sheets, whereas the href attribute must be set to the name of the XSL style sheet. These two attributes are both required in order to wire an XSL style sheet to an XML document. Following is an example of how to use the xml-stylesheet processing instruction with an XSL style sheet:

<?xml-stylesheet type="text/xsl" href="contacts.xsl"?>

In this example, the type attribute is used to specify that the type of the style sheet is text/xsl, which means that the style sheet is an XSL style sheet. The style sheet file is then referenced in the href attribute, which in this case points to the file contacts.xsl.

With just enough XSLT knowledge to get you in trouble, why not go ahead and tackle a complete example style sheet? Don’t worry, this example shouldn’t be too hard to grasp because it is focuses on familiar territory. I’m referring to the Contacts example XML document from Hour 10. If you recall, in that hour you created a CSS style sheet to display the content from an XML document containing a list of contacts. Now it’s time to take a look at how similar functionality is carried out using an XSLT style sheet. In fact, you take things a bit further in the XSLT version of the Contacts style sheet. To refresh your memory, the Contacts XML document is shown in Listing 11.1.

Example 11.1. The Familiar Contacts Example XML Document

1: <?xml version="1.0"?> 2: <?xml-stylesheet type="text/xsl" href="contacts.xsl"?> 3: <!DOCTYPE contacts SYSTEM "contacts.dtd"> 4: 5: <contacts> 6: <!— This is my good friend Frank. —> 7: <contact> 8: <name>Frank Rizzo</name> 9: <address>1212 W 304th Street</address> 10: <city>New York</city> 11: <state>New York</state> 12: <zip>10011</zip> 13: <phone> 14: <voice>212-555-1212</voice> 15: <fax>212-555-1342</fax> 16: <mobile>212-555-1115</mobile> 17: </phone> 18: <email>[email protected]</email> 19: <company>Frank's Ratchet Service</company> 20: <notes>I owe Frank 50 dollars.</notes> 21: </contact> 22: 23: <!— This is my old college roommate Sol. —> 24: <contact> 25: <name>Sol Rosenberg</name> 26: <address>1162 E 412th Street</address> 27: <city>New York</city> 28: <state>New York</state> 29: <zip>10011</zip> 30: <phone> 31: <voice>212-555-1818</voice> 32: <fax>212-555-1828</fax> 33: <mobile>212-555-1521</mobile> 34: </phone> 35: <email>[email protected]</email> 36: <company>Rosenberg's Shoes & Glasses</company> 37: <notes>Sol collects Civil War artifacts.</notes> 38: </contact> 39: </contacts>

The only noticeable change in this version of the Contacts document is the xml-stylesheet declaration (line 2), which now references the style sheet file contacts.xsl. Beyond this change, the document is exactly as it appeared in Hour 10. In Hour 10, the role of the XSLT style sheet was to display the contacts in a format somewhat like a mailing list, where the phone numbers, email address, company name, and notes are hidden. This time around the style sheet is going to provide more of a contact manager view of the contacts and only hide the fax number, company name, and notes. In other words, you’re going to see a more complete view of each contact.

Before getting into the XSLT code, it’s worth reminding you that XSLT isn’t directly capable of formatting the document content for display; don’t forget that XSLT is used only to transform XML code. Knowing this, it becomes apparent that CSS must still enter the picture with this example. However, in this case CSS is used purely for display formatting, whereas XSLT takes care of determining which portions of the document are displayed.

In order to use CSS with XSLT, it is necessary to transform an XML document into HTML, or more specifically, XHTML. If you recall, XHTML is the more structured version of HTML that conforms to the rules of XML. The idea is to transform relevant XML content into an XHTML web page that uses CSS styles for specific display formatting. The resulting XHTML document can then be displayed in a web browser. Listing 11.2 contains the XSLT style sheet (contacts.xsl) that carries out this functionality.

Example 11.2. The contacts.xsl Style Sheet Used to Transform and Format the Contacts XML Document

1: <?xml version="1.0"?>

2: <xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

3: xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

4: xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

5: <xsl:template match="/">

6: <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

7: <head><title>Contact List</title></head>

8: <body style="background-color:silver">

9: <xsl:for-each select="contacts/contact">

10: <div style="width:450px; padding:5px; margin-bottom:10px;

11: border:5px double black; color:black; background-color:white;

12: text-align:left">

13: <xsl:apply-templates select="name"/>

14: <xsl:apply-templates select="address"/>

15: <xsl:apply-templates select="city"/>

16: <xsl:apply-templates select="state"/>

17: <xsl:apply-templates select="zip"/>

18: <hr />

19: <xsl:apply-templates select="phone/voice"/>

20: <xsl:apply-templates select="phone/mobile"/>

21: <hr />

22: <xsl:apply-templates select="email"/>

23: </div>

24: </xsl:for-each>

25: </body>

26: </html>

27: </xsl:template>

28:

29: <xsl:template match="name">

30: <div style="font-family:Verdana, Arial; font-size:18pt; font-

weight:bold">

31: <xsl:value-of select="."/>

32: </div>

33: </xsl:template>

34:

35: <xsl:template match="address">

36: <div style="font-family:Verdana, Arial; font-size:14pt">

37: <xsl:value-of select="."/>

38: </div>

39: </xsl:template>

40:

41: <xsl:template match="city">

42: <span style="font-family:Verdana, Arial; font-size:14pt">

43: <xsl:value-of select="."/>,

44: </span>

45: </xsl:template>

46:

47: <xsl:template match="state">

48: <span style="font-family:Verdana, Arial; font-size:14pt">

49: <xsl:value-of select="."/>

50: </span>

51: </xsl:template>

52:

53: <xsl:template match="zip">

54: <span style="font-family:Verdana, Arial; font-size:14pt">

55: <xsl:value-of select="."/>

56: </span>

57: </xsl:template>

58:

59: <xsl:template match="phone/voice">

60: <div style="font-family:Verdana, Arial; font-size:14pt">

61: <img src="phone.gif" alt="Voice Phone" />

62: <xsl:value-of select="."/>

63: </div>

64: </xsl:template>

65:

66: <xsl:template match="phone/mobile">

67: <div style="font-family:Verdana, Arial; font-size:14pt">

68: <img src="mobilephone.gif" alt="Mobile Phone" />

69: <xsl:value-of select="."/>

70: </div>

71: </xsl:template>

72:

73: <xsl:template match="email">

74: <div style="font-family:Verdana, Arial; font-size:12pt">

75: <img src="email.gif" alt="Email" />

76: <xsl:value-of select="."/>

77: </div>

78: </xsl:template>

79: </xsl:stylesheet>I know, there is quite a bit of code in this style sheet. Even so, the functionality of the code is relatively straightforward. The style sheet begins by declaring the XSLT and XHSTML namespaces (lines 3–4). With that bit of standard bookkeeping out of the way, the style sheet creates a template used to match the root element of the document (line 5); this is indicated by the match attribute being set to /. Notice that within this template there is XHTML code that is used to construct an XHTML web page. Inside the body of the newly constructed web page is where the interesting things take place with the style sheet (lines 9–24).

An xsl:for-each element is used to loop through the contact elements in the document (line 9); each of the contacts is displayed inside of a div element. The specific content associated with a contact is inserted into the div element using the xsl:apply-templates element to apply a template to each piece of information. More specifically, templates are applied to the name, address, city, state, zip, phone/voice, phone/mobile, and email child elements of the contact element (lines 13–22), along with a couple of horizontal rules in between the templates to provide some visual organization. Of course, in order to apply these templates, the templates themselves must exist.

The first child template matches the name element (lines 29–33) and uses CSS to format the content in the name element for display. Notice that the xsl:value-of element is used to insert the content of the name element into the transformed XHTML code. The dot (.) specified in the select attribute indicates that the value applies to the current node, which is the name element. Similar templates are defined for the remaining child elements, which are transformed and formatted in a similar fashion.

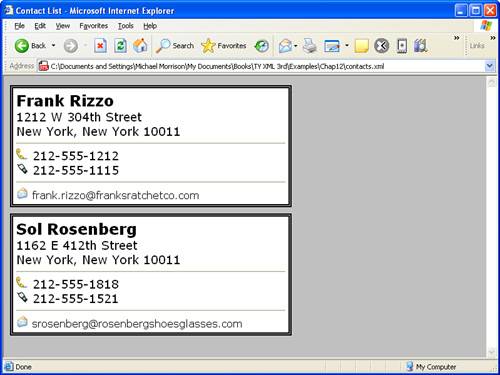

The end result of this style sheet is a transformed XHTML document that can be viewed as a web page in a web browser. Figure 11.2 shows the resulting web page generated by this XSLT style sheet.

Figure 11.2. The Contacts example document is displayed in Internet Explorer using the contacts.xsl style sheet.

The figure reveals how the contacts.xsl style sheet carries out similar functionality as its CSS counterpart from Hour 10, but with noticeably more flair. The flexibility of being able to transform XML code into any XHTML code you want is what allows the XSLT version of the Contacts style sheet to look a bit flashier. Again, this is because the XSLT style sheet is literally transforming XML content into XHTML content, applying CSS styles to the XHTML, and ultimately making the end result available for display in a web browser. Although this style sheet certainly demonstrates the basic functionality of XSLT, it doesn’t touch the powerful transformation features at your disposal with XSLT. I’ll leave that for the next hour.

XSL (Extensible Style Language) is an extremely powerful style sheet technology that is aimed at providing a purely XML-based solution for the transformation and formatting of XML documents. XSL consists of three fundamental technologies: XSL Transformation (XSLT), XPath, and XSL Formatting Objects (XSL-FO). XSLT tackles the transformation aspect of XSL and is capable of transforming an XML document in a particular language into a completely different XML-based language. XPath is used within XSLT to identify portions of an XML document for transformation. XSL-FO addresses the need for a high-powered XML-based formatting language. XSL-FO has limited support in current web browsers, but XSLT and XPath are more than ready to deliver for web-based applications.

This hour introduced you to the different technologies that comprise XSL. Perhaps more important is the practical knowledge you gained of XSLT, which culminated in a complete XSLT style sheet example. Just in case you’re worried that this hour hit only the high points of XSLT, the next hour digs deeper into the technology and uncovers topics such as sorting nodes and using expressions to perform mathematical computations.

The Workshop is designed to help you anticipate possible questions, review what you’ve learned, and begin learning how to put your knowledge into practice.