CHAPTER 16

TRANSFORMING A MANUFACTURING FIRM INTO A SERVICE BUSINESS

“In growing numbers customers consider manufacturers of physical products service providers, albeit often mediocre service providers. In order to maintain their competitive advantage it is time for manufacturers to start transforming themselves into service businesses.”

INTRODUCTION

In previous chapters we have discussed what it means to be a service organization, and to manage it and its customers with a customer focus in order to support the customers’ activities and processes in a value-supporting way. Here the need for traditional manufacturers, such as firms in metal, forest, electronic, chemical, IT and other industries, to find new sources of competitive advantage is discussed. Transforming into a service business is one logical way of getting closer to the customers and finding new opportunities to support customers’ processes in a more valuable manner than before. After reading the chapter the reader should understand the reason for manufacturers to transform into service businesses, and why this requires a strategic turnaround of the whole firm to be fully successful. The reader should also know what changes are needed to become a service business, how the product should be understood and what steps should be taken, according to the CSS (Conceptualizing, Systematizing, Servicizing) model, to make a transition.

THE CHALLENGE FOR MANUFACTURERS

It is generally agreed that markets have moved into a service economy, where the firm which can provide its customers with not only the best core solution, such as a physical product (or a core service), but also better overall value-supporting service than the competitors will survive. Product manufacturers increasingly voice a need to move into a service business mode. The traditional supplier–customer dyad has long been challenged by forces in the marketplace. To be able to support their customers, suppliers have had to move into networks with other suppliers and the customer’s customer becomes a part in the chain that has to be considered. Changes in the business environment relating to business-to-business markets can have dramatic consequences for firms. A competitive advantage cannot be achieved and maintained by traditional means. A supplier who, in a competitive market, only offers the core solution to its customers in the form of a physical product, from small-scale products to large investments such as a paper machine, will, among other things, soon find that the pressure on price gradually grows from what it used to be. The reason for this is quite obvious. As customers do not perceive any other support to their processes by a supplier than what the product offers, and as there is an abundance of competing offerings on the market, it is only natural for a buyer to look at price as a major and often even the major purchasing criterion. What the supplier traditionally does is offer its customer a technical solution to a customer process, for example a production, administrative, financial, marketing or HRM process, but not explicitly a value-creating support to this process that has a favourable effect on the customer’s business and commercial processes. The competitive advantage once created by a technological solution is in most industries long gone. And when new technological solutions are introduced, the advantage lasts less time than ever.

Furthermore, offering service, such as maintenance and upgrading, to an installed base provided by the manufacturer may provide a steady stream of revenues on top of those from delivering the product. Although the unit revenue of a single product transaction is often higher, the service-based revenue provides a continuous cash flow.

A value-creating support to a process provided by service requires, first of all, that the customer can perceive and preferably also calculate the effects on the outcome of the process that is supported. Second, a calculable longer-term effect on the customer’s business process, that is, on the customer’s revenue-generating capability or on its cost level, or on both, and ultimately on its profits, should at least approximately be visible for the customer. Or if for some reason it cannot be calculated, the existence of such a positive effect must at least be recognized and accepted. Otherwise the value of service remains abstract and incomprehensible, and difficult to evaluate by the buyer. If this is the case, price becomes the dominating decision-making criterion.

In order to provide more support over a longer time period than the physical product provides, suppliers often turn to various types of services, traditionally called after-sales services, or industrial services. For example, a physical product can be offered together with a service contract. This may be an improvement, but it turns out that it is often difficult to persuade customers to pay for these services. Moreover, the product as the core is often still managed and delivered with more of a product-focused than a customer-focused strategy. Hence, new visions and new actions are needed.

SERVITIZATION: INFUSING SERVICES INTO A PRODUCT OFFERING

In the management and also marketing literature the need for product manufacturers to turn to service has been recognised.1 Oliva and Kallenberg offer a four-phase process: (1) consolidating mostly existing product-related services, (2) entering a market of servicing an installed base, and (3) expanding to services based on customer relationships and developed from existing processes. The fourth phase would cover situations where the firm takes over an end-user’s operation, and for example manages a production plant.2

Almost invariably, the literature on how to transform product manufacturers into service businesses suggests that this transformation takes place through a gradually increasing infusion of services into a product-based offering (service infusion).3 A more commonly used term for this process is servitization. Andy Neely summarizes the discussion of what is meant by servitization with the following explanation:

In essence servitization is a transformation journey – it involves firms (often manufacturing firms) developing the capabilities they need to provide services and solutions that supplement their traditional product offerings.4

Hence, according to the servitization and service infusion approach, product manufacturers can move towards a service business mode, and eventually become a service firm, basically by gradually adding more service activities to their core offerings, which remain physical product-based. We do not believe that this would work. For this approach to be successful, a growing number of services should automatically change the overall strategy of the firm. However, if the core of the offering remains a resource, such as a physical product, there is a substantial risk that the firm’s strategy will remain product-based, and the accompanying services will be treated as add-ons and the dominating culture in the firm will continue to be product-centric.

In our view, servitization and service infusion is, at best, a transition stage. For a final transformation to take place, the manufacturing firm’s overall strategy has to be service-based, and the core of the offering has to be value-creating support to customers, not a physical product or any other type of resource. In the offering, products and service activities have to merge into an integrated process, which aims at supporting the customers’ processes and ultimately their business processes. Offering value-laden resources must be replaced by providing value-creating support. This means that unlike product-based offerings which tend to be transaction based, service offerings are based on relationships. Consequently, firms which are in a true service business mode have to change their business model from a transaction-based model to a relationship-based model.5

In a study of the effects of servitization on firm value, it was observed that adding services to a core product may add to the manufacturer’s value, but this requires a substantial level of service sales. It was also noted that if services offered are closely related to the core product, this effect grows.6 However, in the recent literature the weaknesses and insufficiencies of a servitization approach are clearly recognized. In a recently reported study about European manufacturing firms it was observed that in reality product offerings are supplemented only with a limited number of services.7 It has also been claimed that transforming into a service business mode is an evolutionary process rather than a transition from one phase to another8 and requires strategic rather than incremental change.9

This chapter will discuss how to transform from a product manufacturing firm into a service business by taking a service perspective and adopting a service strategy, rather than by following a servitization process.

ADOPTING A SERVICE PERSPECTIVE: A SERVICE STRATEGY APPROACH

The question is: What is meant by providing better service in a manufacturing industry? We do not believe that it is enough to add better industrial services or after-sales services to the core product. In this book we have defined service as supporting the customer’s everyday activities and processes in a value-creating manner.10 Hence, taking a service perspective, or adopting a service logic in a manufacturing firm would mean that the supplier alone, or together with network partners, develops and implements holistic offerings that successfully support its customers’ processes, for example, a production process, so that this process functions better than without the support of this offering or with the support of some other offering. Moreover, this offering should have a favourable and preferably quantifiable effect on the customers’ business processes, in terms of growth and renevue-generating opportunities and/or cost savings.11

The next important question is: What does this value-supporting offering include? Does it only include industrial services such as maintenance, repair or training? The answer is definitely no. Following a service perspective, an offering with which a supplier provides service in a value-supporting manner over time cannot include only after-sales and other service elements, it has to include the total support, thus encompassing the support provided by the physical product as the core solution as well as by service processes, such as deliveries, installation, repair, maintenance and customer training, and hidden services, such as invoicing, complaints handling, extranets, product documentation and ad hoc interactions between people. In this way a true service offering is provided, and not a product offering accompanied by services. In Chapter 1, hidden services were defined as activities that customers are influenced by which by the firm are considered administrative, financial, legal or technical routines, without any impact on the customers’ preferences. They are, therefore, treated and implemented as non-service. Badly managed and handled hidden services, such as complaints handling and invoicing, easily create emotional stress for customers and, in addition, unnecessary and unwanted sacrifice in the form of time spent, for example, on solving a service failure, checking the specification and correctness of an invoice or figuring out the meaning of product documentation, and costs created by this. In Chapter 6 such costs were discussed and termed indirect and psychological relationship costs.

Adding more services one by one to a product-based core offering may be counterproductive.12 To have a major effect on a firm’s competitiveness, servitization must lead to a strategic development of the entire manufacturing business into a service business, including its traditional product manufacturing part. Then a service perspective and service logic drives the whole business, both strategically and tactically.13

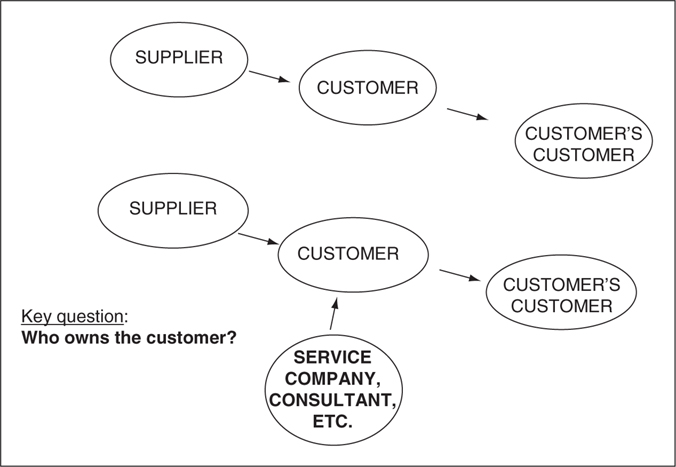

THE THIRD-PARTY THREAT

In addition to the price pressure from customers, and the fact that in most industries the technical solutions embedded in a physical product have become more or less similar, there is another threat that suppliers in manufacturing industries have to be aware of and handle. This can be called the third-party threat. This is illustrated in Figure 16.1.

In the upper part of the figure a traditional supplier–customer–customer’s customer chain is illustrated. In this situation, by providing the customer with a core solution, for example, a production machine or computer hardware, more effectively than competitors also offering core solutions only, the supplier can successfully develop a working relationship with its customer. As customers have traditionally considered the technical specifications of the product the essence of a successful solution, by offering a competitive technical solution the supplier has been able to claim and keep ownership of the customer.

However, this situation is changing. In the lower part of the figure a quickly emerging situation is illustrated. Customers’ preferences are changing from considering the technical specifications as the essence of a successful solution to looking at how efficiently and effectively a process, such as a production or an administrative process, runs using a given technical solution and other support, such as serviceability of the technical solution, repair, maintenance, training and call centre or website advice. Customers are even looking for support in operating a production line or a whole plant. Moreover, customers start to look at the effect on their business process of how well a given process functions, and at possibilities to serve their customers successfully. At this point, from having been tactical suppliers, service companies and consultants offering services that help the customer run a process successfully gradually gain a strategic position in the customer’s business. When a customer decides to outsource, for example, the operation of a production line or a plant to a third party, such as a service company, the position of the supplier becomes shaky.

FIGURE 16.1

Who owns the customer: the third-party threat.

What has happened to the supplier–customer–customer’s customer chain? The more the third-party actor gains a strategic position, the more the position of the supplier, who traditionally had this position in relation to the customer, declines and eventually becomes merely tactical. The supplier does not own the customer any more, the third-party actor does. This means that decisions regarding the supplier’s involvement with the customer are no longer primarily taken between the supplier and the customer, but between the customer and the third-party actor. The supplier may not even be asked. Hence, ownership of the customer has slipped away from the supplier to the service firm or consultant, or whichever type of firm has taken this position. The risk grows that the supplier becomes a subcontractor to the third-party actor.

HOW TO MAINTAIN A SUSTAINABLE COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE: ADOPT A SERVICE LOGIC

What can a manufacturing firm that is in the supplier’s position in Figure 16.1 do? One option is to continue to compete with price. In some markets and in some customer segments it works, but a price strategy is sustainable only if the firm has a lasting cost advantage. In the long run it seldom works. Moreover, a lowest price strategy also makes it difficult for a firm to invest enough in research and development, in technology and service development.

There is also another quite obvious option. The manufacturer can transform itself into a service company. Instead of remaining in a manufacturing business mode it can move into a service business mode. On top of its technological and product knowledge it can strive to create the same capabilities as a service company and consultant as third-party actors have, and thus create an even stronger strategic position in relation to the customer than the third-party actor can ever develop. Of course this does not mean that the manufacturer has to do everything. It can very well outsource some processes, such as deliveries or maintenance, but in this case it is the supplier which is the outsourcer, not the customer who uses a third party’s services. Consequently, the risk that a third-party threat develops is minimized.

Today it is seldom possible for a traditional manufacturer to create a sustainable advantage with a price strategy or based on technological development with a product strategy. The only option left is to adopt a service perspective and strategically and tactically develop into a service business.14 This, however, is easy to say, but turns out to be very difficult to do. It normally demands changes in attitudes, business mission and strategies, organizational and operational structures and leadership approaches. It takes a service-focused mission, service business-based strategies and a service culture. (These issues have been discussed at length in previous chapters.) In many cases, attitudes seem to be the most problematic issue. Without a change in attitudes throughout the entire organization, none of the other required changes will take place. However, it should be noted that unless top management truly embraces a service culture first, an organization-wide cultural change will not take place.

However, what part of the business should adopt a service logic? Is it enough that a separate service operation, industrial services, is transformed into a true service business? The answer is no. This is servitization and service infusion into manufacturing without reaching the ultimate goal, a true service business. To achieve a sustainable competitive advantage the entire firm, including its manufacturing part and service part, has to adopt a service logic and become a service business where the manufacturing and service operations are integrating into one business. There are three reasons for this:15

If the industrial services part – for example, engineering, consultancy, software supply, repair and maintenance, customer training, product upgrading – is developed according to a service logic, but the manufacturing business is not, the former becomes closer to understanding its customers’ value creation and geared towards supporting it (outside-in management), whereas the latter part of the business inevitably remains focused on manufacturing and the customers’ technical processes (inside-out management). However, the customers are the same both for the manufactured product and for industrial services, and therefore customers easily get confused and upset by the inconsistency in approach.

It is difficult for two different logics and cultures to exist and thrive in an organization. Normally, the manufacturing logic which exists in a much larger part of the organization and which has much older and deeper roots in the firm and its culture will become a hindrance to the development of a much younger and stranger service culture. In the end, the service culture will fade away and the whole business will slip back to the dominating manufacturing culture. If top management is in a manufacturing mode, the risk that this will happen is overwhelming.

If an industrial service business has been successfully established, it easily undermines the image of the product business in the minds of the firm’s customers. The service business represents solutions that are more attractive to customers than stand-alone products. The product business is perceived, relatively speaking at least, as more product-oriented and less customer-focused. Eventually customers consider stand-alone products more as commodities, which leads to an increasing price pressure.16

TRANSFORMING INTO A SERVICE BUSINESS–THE GAME PLAN

Being a service business means that a firm does not only provide its customers’ resources, such as physical products alone or together with stand-alone services, for their use. Instead the firm offers customers value-supporting processes, integrating a set of resources – physical products, services (including hidden services), people, systems, information – which in interactions with the customers and the customers’ resources, facilitate a customer process, such as a production line or sales automation. If this functions well, value is created in this customer process and, furthermore, in the customer’s business process as well in the form of a better revenue-generating capacity over time, lower costs of being a customer over time (lower relationship costs), or both, and eventually improved profits.

In business-to-business markets, supporting, for example, a customer’s production process in a way that has a positive effect both on the revenue side and the cost side, means that in addition to the core process, a multitude of other customer processes have to be supported in a successful way as well. Examples of such processes are the customer’s warehousing, repair and maintenance, need for basic product knowledge and ad hoc information, payment and cost control, problem solving and failure management. Only by supporting all these and other processes, in addition to the production process, is the customer’s business and commercial process backed up in a successful way. If the supplier manages to do so with adequate, customer-focused resources, a trusting relationship can be expected to emerge and the ‘customer’s heart and mind’ can be won.17

As MacMillan and McGrath18 point out in a discussion of finding ways of differentiating businesses, a supplier cannot concentrate on providing the customer with a good product only, it has to take a comprehensive look at the customer’s processes. According to them, the supplier should ask the following questions:19

• How do customers become aware of their need for your product or service?

• How do customers find your offering?

• How do customers make their final selections?

• How do customers order and purchase your product or service?

• How is your product or service delivered?

• What happens when your product and service is delivered?

• How is your product installed?

• How is your product or service paid for?

• How is your product stored?

• How is your product moved around?

• What is the customer really using your product for?

• What do customers need help with when they use your product?

• How is your product repaired and serviced?

• What happens when your product is disposed of or no longer used?

Going through these and possibly other questions, the customer’s experience is analysed. A manufacturer as a service business has to support all of the customer’s processes, which are important to the customer’s commercial outcome, in a satisfactory way. Some of these processes are more critical to the customer and its business process than others, and those processes have to be supported especially carefully. However, it must be realized that, in the end, all processes are important to the customer. Some activities can be outsourced, but in order for the supplier to maintain its strategic position in relation to its customers, the supplier has to stay in control of the network used and of outsourced processes.

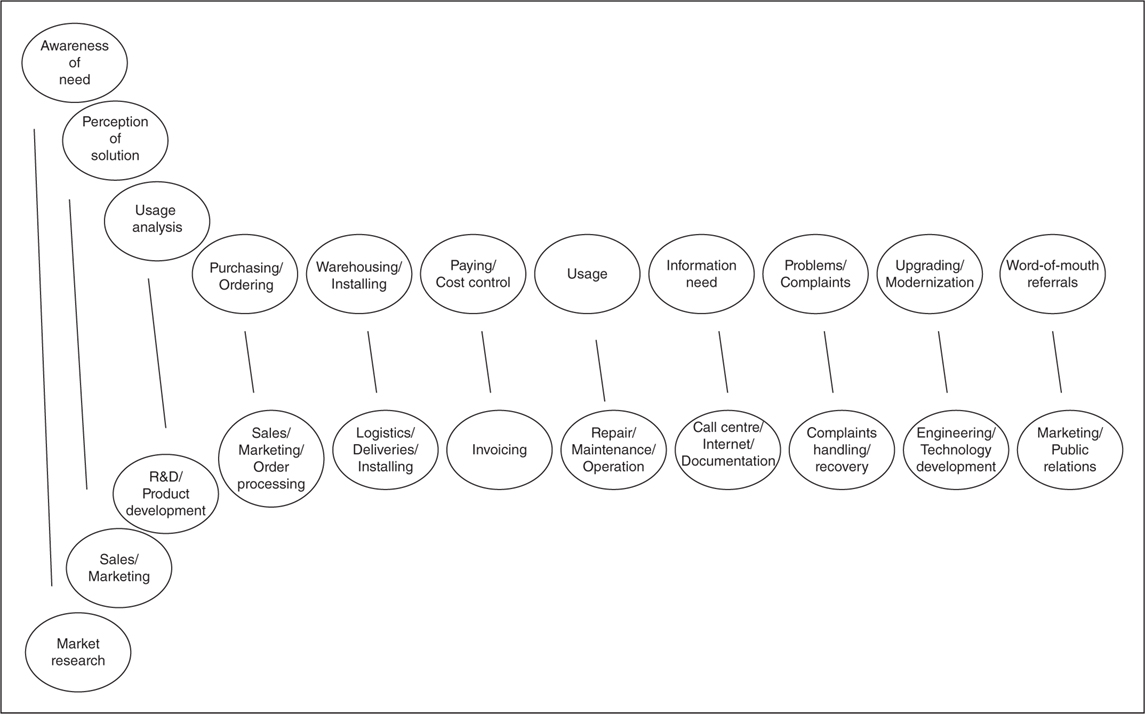

In Figure 16.2 a typical chain of processes of a customer and a corresponding chain of processes of a supplier are illustrated. In the figure they follow each other in a chain-like order. However, in reality the order may be different, and some processes may be simultaneous or iterative. For the sake of simplicity they are depicted as a chain.

The customer chain includes awareness of needs, perception of a solution, purchasing and ordering, warehousing and installing, payment and cost control, usage, information needs, problems and complaints, upgrading and modernization and, finally, word-of-mouth referrals.

The supplier chain includes market research, sales and traditional marketing, order processing, logistics and deliveries and installation, invoicing, repair and maintenance and process operation, call centre and Internet advice and documentation, complaints handling and recovery, engineering and technology development, and public relations and marketing.

These lists are, of course, only examples. The important thing is, however, that the customer’s process and the supplier’s process are linked to each other and interact with each other, that is, that the supplier’s activities are truly geared towards the requirements of the corresponding process on the customer side. For example, the supplier’s logistical process should meet the customer’s warehousing process with a delivery system that supports value creation in the customer’s goods-handling processes. As another example, the supplier’s invoicing system should meet the requirements of the customer’s payment and book-keeping and cost control system. Developing this system includes issues such as specification of the invoice, number of invoices sent during a given period and the receiver to whom invoices are sent, and so on.

Moreover, supplier processes that, when supporting a customer’s processes, need to function together or at least be informed about each other’s contacts with the customer must work closely together, share information and perhaps do joint planning. Such processes are, for example, product development, repair and maintenance and modernization. Far too often people in these processes never see each other or even talk to each other, either when planning or executing.

In the supplier firm the following questions should be asked:

• Do we know which customer processes are influenced by our activities and processes?

• Do we know how these customer processes function and who is involved in them?

• Do we know how these customer processes influence the customer’s business process, either through a revenue-supporting or a cost-creating effect?

• Do we know which of the customer’s processes are critical to the customer’s business process and commercial outcome?

• Do we know how the way we handle our activities and processes influences the customer’s processes today?

• Do we know how the customer’s processes could function more efficiently and effectively than today and support the business process better?

FIGURE 16.2

The customer lifecycle and supplier support chains.

• Do we know how we could support the customer’s processes more efficiently and effectively with a higher value-creating effect than today?

• Do we know the customer’s customers’ processes well enough so that we can advise the customer about how to serve their customers better than today?

Only after having asked these questions and found satisfactory answers to them is a firm prepared to develop a comprehensive offering to support the customer in a value-supporting manner. Before finding satisfactory answers the manufacturing firm does not know the game plan for operating as a service business and probably cannot successfully service its customers in a competitive way.

WHY IS A SERVICE BUSINESS APPROACH NEEDED?

The core competence of a traditional manufacturing firm is mainly related to how to manage manufacturing processes and an understanding of the customers’ processes in a technical sense. Therefore, such a firm offers its customers a technical solution for a technical process, for example for a production process, administrative process or sales process. This technical solution should make the customer’s technical process function more efficiently. The effects on the customer’s value creation and business process, not to say the processes of the customer’s customers, are normally not considered in an explicit way.

A manufacturer that wants to ensure it can stay in a strategic position in relation to its customers has to be able to support the customers’ various processes in a way that helps them create value in these processes (value-in-use) such that the customer’s business process is also supported in a value-creating way. As the previous section demonstrated, the core solution, the physical product as a technical solution, is not enough to achieve this. Traditionally, in a manufacturing firm the main knowledge base is geared towards knowledge about technologies, products and manufacturing processes. This knowledge base is still of paramount importance for being a successful service business. However, to compete successfully in the new situation, in relative terms, the required main knowledge base is not in manufacturing processes, technologies and products. Today, the traditional knowledge base can be characterized as a prerequisite for success, but the main knowledge base required is elsewhere.

To compete successfully for customers today, the main knowledge base has to be:

• Knowledge about customers’ processes and about how customers create value for themselves in these processes.

• Knowledge about how to support the customers’ everyday processes, so that value (value-in-use) emerges in them.

• Knowledge about how supporting customers’ everyday processes successfully contributes to commercial value for the customer, for example by providing growth and revenue-generation opportunities and/or cost savings.

This knowledge is what a service business is built upon. Service is support and the logic of a service organization is to know how to support its customers’ everyday activities and processes.

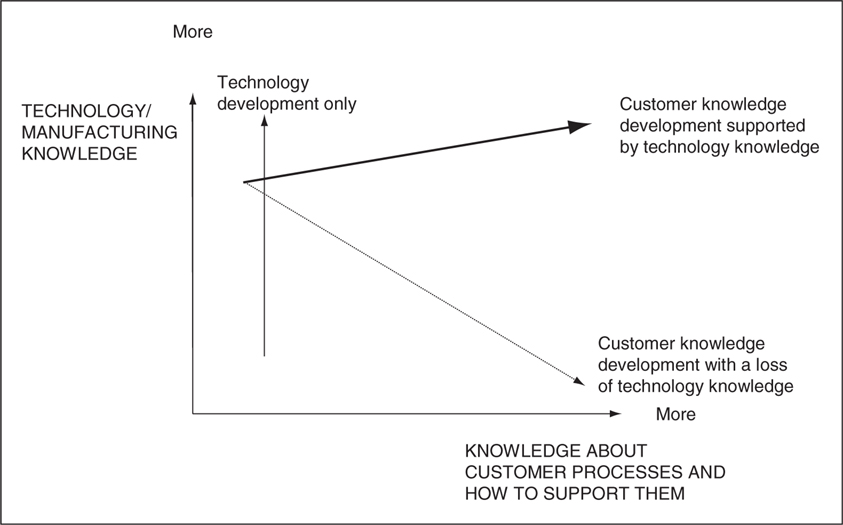

This refocusing of the required knowledge base does not mean that the traditional knowledge of a manufacturer is less important, probably in most situations it is the contrary. In Figure 16.3 the change in focus of how to improve the operations of a firm is illustrated schematically.

FIGURE 16.3

Moving towards a service business knowledge base in manufacturing.

In the figure a thin line shows the traditional way of creating a competitive advantage based on a knowledge base geared towards technology and manufacturing processes. The technology knowledge deepens and the level of technology goes up, but the knowledge geared towards understanding customers’ everyday processes and business process, and towards how to support them, other than with a technical solution for a technical process, remains on the same level as before. In value terms, this development is based on the idea that value for customers is embedded in the products developed and offered for the customers’ use (value-in-exchange).

The dotted line illustrates the worst development that can happen. The manufacturer devotes time to create an understanding of the customers’ processes, but does not maintain or when needed improve the technological knowledge. In that case the firm loses its capability to offer technical support in the form of products to its customers. The customers may like the supplier’s way of interacting with them, but not the way they help them keep their processes going, for example a production or administrative process. The prerequisite for being a customer-focused service business has been lost. Such a supplier will not survive long on the market.

The thick line in Figure 16.3 indicates the way to become a service business. The manufacturer must obtain an in-depth knowledge about all its customers’ processes (compare the game plan in Figure 16.2) as well as how they, and through them the business process, can be supported so that value is created in all processes. The customers are the key to value creation. They create value for themselves supported by the supplier,20 and this value is created in the customers’ processes where the support of the supplier is used (value-in use).

THE CUSTOMER’S VALUE FORMATION PROCESS

The core competence of a service business is related to an understanding of the customer’s value creation and business process and how to manage a system for supporting customer’s value creation. Based on its main knowledge base of understanding the customers’ activities and processes and their value creation, and understanding how to support this value creation, a manufacturer taking a service business approach would strive to provide support to its customers’ value-creating processes and business processes, and thus to total value creation. When doing so, it would probably also provide support for its customers’ capabilities to serve their customers and support the customers’ commercial outcome. This is achieved by offering customers, first of all, technical solutions to technical processes, but in addition, by managing all of its activities and processes, including hidden services, that have an impact on the customers’ total value creation, and hence also on their preferences towards the supplier, in a customer-focused and value-supporting manner throughout the customer relationship lifecycle.

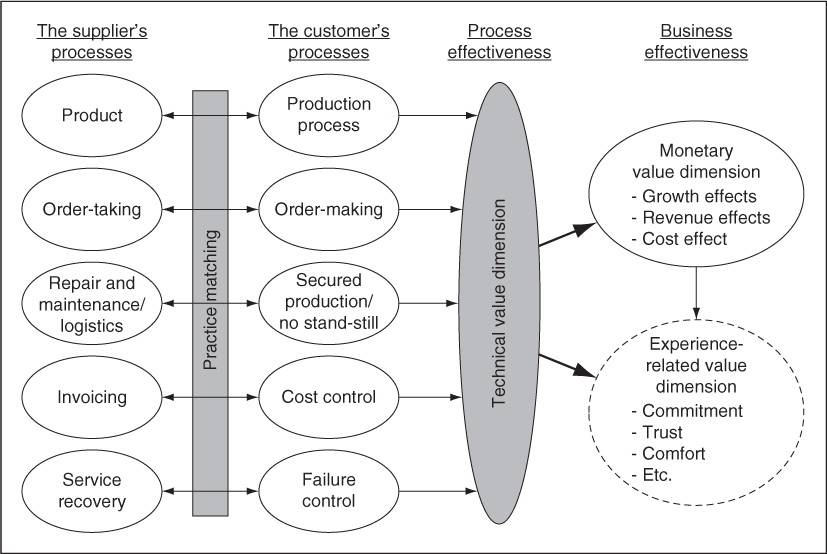

In Figure 16.4 a hypothetical example of how a customer’s value creation is supported through a four-stage process is schematically illustrated (compare Figure 6.10 in Chapter 6). The following steps should be taken:

Identify customer processes which are critical to the customer’s commercial result, that is, to the customer’s business effectiveness.

Match the customer’s key processes and the supplier’s corresponding processes (practice matching), such that the customer’s processes are successfully supported (creates process effectiveness), and facilitate the customer’s commercial result in a value-creating way (creates business effectiveness).

FIGURE 16.4

Supporting customers’ value creation – an example.

Manage the supplier processes such that the customer’s identified key processes are effectively supported in a technical sense (technical value dimension).

Make sure that the technical support to the customer’s processes is transformed into successful business effectiveness (monetary value dimension), and creates a favourable experience as well (experience-related value dimension).

In Figure 16.4 the core of the offering is exemplified with a physical product of some kind. The customer processes which are considered critical to the customer’s commercial result are the following (the supplier’s corresponding processes are in brackets): the production process (product), order-making (order-taking), secured production minimising stand-still time (repair and maintenance and logistics), cost control (invoicing), and failure control and correction (service recovery).

The supplier must first identify these pairs of critical processes, and thereafter initiate a practice matching process, where the way these processes are practised is analysed. The aim is to align the supplier’s and customer’s activities, competencies and processes, such that the customer’s different processes are successfully supported. Who adapts to whom is a matter of, among other things, the two parties’ strategies, power position, and also understanding of the potential of the service perspective.

Then the supplier should integrate support to each of the customer’s key processes into one offering, and then manage its processes in a way which creates a technical value21 in each of the customer’s processes, and consequently create process effectiveness. This value dimension can be measured, for example, in technical, temporal, or sometimes even monetary terms, such as quality of production output, amount of scrap, time from order to delivery, or lost sales due to stand-still or delayed problem recovery. Sales often aim at supporting process effectiveness, and often the effectiveness of a core customer process only. As a consequence, technical specification and price become key sales arguments on one hand, and dominating purchasing criteria on the other hand. By taking the process one step further, sales can move the purchasing agent’s interest into value for the customer on the commercial level, which leads to value-based sales. Sales and selling is, however, not part of the scope of this book.

The final step is to demonstrate for the customer how the combined process effectiveness in the customer’s key processes leads to a monetary commercial value or business effectiveness: which are the effects on the revenue side through possible growth or premium pricing opportunities, and which cost savings effects can be expected to occur. In Chapter 6 on return on service and relationships we showed how these monetary effects can be calculated.

Furthermore, positive effects on business effectiveness and on the monetary value dimension can be expected to have a favourable impact on experience-related value dimensions, such as commitment to the supplier, and trust and comfort in doing business with this supplier.

THE BENEFIT FOR A MANUFACTURING FIRM OF TAKING A SERVICE BUSINESS APPROACH

From transforming its approach towards customers into a service business approach at least the following benefits can be expected for a manufacturer:

• The firm becomes truly customer-focused and learns to understand not only its customers’ technical processes, but how value is created in those processes and in the customers’ business processes as well.

• By doing so, the firm can develop more valuable technical solutions than before as well as truly customer-focused and service-based ways of supporting all critical customer processes (warehousing, installation, maintenance, invoice processing, problem solving, etc. – compare Figures 16.2 and 16.4).

• The firm becomes more relevant for the customers’ business processes than any third-party actor and can maintain a strategic position in relation to its customers.

• The firm has the potential to help their customers serve their customers in a more efficient and effective, and therefore probably also more profitable, manner.

• By developing its solutions and ways of managing its customers as a service business, the firm differentiates its offering in a way that for competitors is substantially more difficult, sometimes almost impossible, to copy.

• In the final analysis, a service business approach enables the firm to strengthen its customer contacts and develop them into trustworthy and sustainable relationships that are less vulnerable to competitor actions and third-party threats, and hence a source of better and more profitable business.

Of course, not all customers are interested in getting into such close contact with a supplier and are not ready to open up for a supplier. For some customers the technical solution is the only part of an offering to consider, and the price remains the most important purchasing criterion. For such customers, or sometimes even for markets dominated by such customers, a service business approach may not be effective. For all other customers and markets such an approach may even be inevitable in the future for maintaining competitive advantage or even just for staying on the market.

A service business approach can be important for any type of firm in business-to-business markets, not only for those offering tailor-made solutions in markets where there is a need for after-sales service. Standardised products are myths and commodities only exist in the minds of managers who have not had the imagination to differentiate them by developing other interfaces with the customers that inevitably always exist.22 Offerings to customers and customer contacts with even simple products can be developed in this way. By taking a service perspective and adopting a service logic, undifferentiated, commodity-type products can be differentiated. The supplier needs to find out what would make a customer perceive the product and the supplier differently from the industry standard. There is always something in the customer relationship which a customer appreciates when it is offered and handled in a new and different way. It can relate to deliveries or delivery times, warehousing, product documentation, the invoicing system and the structure of the invoice, access to people, systems and information, or just anything that a customer may perceive as different and valuable compared to standard behaviour. By finding out what it is and offering it, the firm adds a customer-focused value-enhancing support to the core product. The supplier moves from a product manufacturing and delivery mode to a service business mode, and becomes a service firm.

TRANSFORMING INTO A SERVICE BUSINESS

In order for product manufacturers to become service businesses, two fundamental requirements have to be taken into account:

Becoming a service business is a strategic choice. There must be a strategic decision to be and perform as a service business. Such a strategic decision demonstrates top management’s wish and determination to transform the firm from a resource-delivering product business into a value-supporting service provider.

Performing as a service business and providing value-supporting service to customers (and other stakeholders) requires a dominating service culture throughout the firm. Unless such a culture can be created, the implementation of a service perspective and a service strategy will not be successful. In addition to employee training, internal communication and other efforts that may be necessary, creating and maintaining a service culture requires the continuous support through top management’s leadership (see Chapters 14 and 15 about internal marketing and service culture).

The case study on the Normet Group at the end of the chapter clearly illustrates these requirements.

Compared with a manufacturing approach, taking a service business approach requires at least three fundamental changes in the business logic. These changes are:

Redefining the business mission and strategies from a service perspective.

Redefining the offering as a process.

Servicising critical elements in the customer relationships.

REDEFINING THE BUSINESS MISSION AND STRATEGIES FROM A SERVICE PERSPECTIVE

Being a service business means that the firm does not view its manufacturing part as one business and industrial services as another business with different strategies and planning processes. The manufacturing part must be integrated with all other activities – service processes as well as hidden services – into one total continuous support to the customers’ processes over the customer lifecycle. The business mission is not to provide customers with excellent or high-technology resources only for their use, such as physical products as a technical solution, but to provide customers with excellent support to their processes so that value is created in them and in the customers’ business and commercial processes. Strategies have to be formulated accordingly.

This support is formed by a continuous flow of technical solutions, products, deliveries, customer training, invoicing, service recovery when needed and handling of complaints and problems, advice, repair and maintenance service, joint product and service development, and research and development, upgrading and modernization of installed equipment, etc. (see Figures 16.2 and 16.4). This flow of activities takes place in a continuous process of supporting the customers’ processes in a value-creating manner. In this way the customer is truly served with physical products and technical solutions, service processes (deliveries, training, maintenance, etc.), administrative and legal routines (hidden services such as invoicing and complaints handling), infrastructures (logistical systems, extranets, etc.), information (product documentation, advice, etc.) and people.

REDEFINING THE OFFERING AS A PROCESS

As the previous discussions of a service business-focused mission and of how customers’ business effectiveness is supported demonstrated, it is not enough to just provide customers with a technical solution for a technical process. This is only one element of a process of providing customers with all the support needed for them to be able to create adequate value in their processes and for their business. Hence, the offering of a manufacturing firm, which used to be a physical product, is dead in its traditional form. The physical products still exist, of course, but from having been the output of the manufacturer’s production process they become one input among others into the customer’s value-creating process. The physical product becomes a resource alongside a host of other resources needed in the constant flow of supporting the customer’s processes. This flow of resources and activities takes place in a continuous process. Hence, a service business’s offering is the process. This process takes the place of the traditional product.23

SERVICIZING CRITICAL ELEMENTS IN CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIPS

As was shown in the previous section, a firm’s productive (e.g. products), administrative (e.g. websites), financial (e.g. invoicing), legal (e.g. complaints handling) and other processes should be considered inputs into customers’ processes, where the goal is to support value creation in those processes, and ultimately the customers’ business processes. They have to be turned into true service for customers, or servicized. So, servicizing can be defined as turning all elements in a customer relationship, regardless of their type and nature, into value-supporting inputs into the customers’ processes, i.e. turning them into service for customers. Servicizing the supplier’s resources and activities makes a firm a true service business. Servicizing is not the same as servitization. The latter means that a growing number of services are added to a core product. Servicizing relates to the actions taken by a firm to transform resources and processes into a holistic offering, including products and recognized and hidden services into value-supporting processes that serve the customers’ processes and business.

Servicizing requires that:

• All customer contacts and all resources and activities in those contacts, and all interactions with the customer, are analysed and the effects they have on the customer process they influence are assessed.

• If this effect is neutral or even negative, that is, no value support to a customer process is achieved, or the customer’s process is affected unfavourably (unnecessary and unwanted costs are created for the customer, the customer’s revenue-generating capability is hurt, or both; the value of the core solution is hurt by value destroyers), an assessment is made of how critical this activity is for the customer’s value creation and commercial outcome (either perceptually or in financial terms, or both).

• Resources and activities with a neutral or negative effect are developed so that, in the future, they function as value-supporting service and not as value destroyers in the customer relationships.

In principle, anything can be servicized. It is just a matter of management attitude and the adoption of a service logic and customer focus. What in any given case should be servicized depends on what is critical for the customer, the competitive situation at hand and a long-term cost–benefit analysis. However, changing the focus and servicizing elements of the customer relationship will probably not create substantial extra costs, if any. Moreover, doing so can easily lead to cost savings for the suppliers. When the firm performs in a more service-focused manner, mistakes are avoided and unnecessary queries and complaints do not have to be attended to. Therefore, less resources, time and money are required for the unproductive processes of sorting out problems, correcting mistakes and discussing, negotiating and sometimes even quarrelling with customers. All badly-handled activities that lead to unnecessary costs for customers (rising relationship costs) normally at the same time also lead to similar unnecessary relationship costs for the supplier (see Chapter 6).

In Table 16.1, examples of how various systems, resources and activities in customer relationships can be servicized are described.

Examples of how systems, resources and activities in customer relationships can be servicized.

Products |

Products are traditionally seen as outputs of production processes. Servicizing products requires that they are considered inputs into the customers’ processes. Tailor-making products, using CAD/CAM and other techniques and bringing customers into design and production processes, and mass customization are examples of this. Other examples are making products easier to maintain, easier to make operational, and easier to handle. However, depending on the situation and the requirements of the customers, servicizing may also mean that products are standardized. It all depends on what is the most effective way of supporting value generation for customers. |

Logistics |

Just-in-time logistics is a well-known means of servicizing order-making, deliveries and warehousing. By this strategy a supplier aligns its logistical processes to the customer’s processes in order to minimize the customer’s costs of keeping products in stock. |

Deliveries |

Deliveries as a separate part of logistics can be servicized, for example, by customizing timetables and by keeping customers informed about the progress of a delivery. |

Information |

Documentation about how to use machines, software and other solutions can be servicized by turning it into real knowledge for customers. Knowledge requires that the information is easily retrievable and understandable and can be used immediately. |

Extranets and websites |

Servicizing extranets and websites requires that they are designed so that users can easily navigate them and find the information they are looking for in such a format that it can easily be transformed into usable knowledge. |

Managing quality problems and service failures |

If there is a problem with goods quality or a mistake or service failure has occurred, servicizing requires that such incidents are managed according to the principles of service recovery. The customers have to perceive that the supplier or service provider cares for their situation, quickly finds a solution, and compensates for losses that they may have suffered. |

Invoicing |

By developing an invoicing and payment system and by designing invoices so that they are easy to understand, check and process by customers, this element of customer relationships is turned into a cost-saving service for customers. Making sure that mistakes are avoided is, of course, also part of servicizing invoicing. |

Product and service development |

Bringing customers into the processes of developing and designing new resources and processes, such as products and services, potentially makes it possible for a supplier or service provider to develop solutions that better fit customers’ processes and, therefore, also more effectively support their value-creating processes. This may improve the revenue-generating capacity of customers, and reduce their costs, and is therefore an example of how to servicize the customer relationship. |

R&D |

Bringing customers into the processes of basic research and development may have similar effects to the ones discussed above. |

Etc. |

There are many more elements of the customer relationship where servicizing is possible. |

As can be seen from the examples in the previous section, there are several ways of servicizing customer relationships already at least partly in use (for example, involve customers in the design and development of products and other resources and processes, just-in-time logistics and joint R&D). However, the challenge is to not just take some elements of a relationship in isolation and treat them from a value-supporting perspective. As long as other elements of a relationship are not designed in a similar manner, the customer’s process may still be hurt and value destroyed.

DEVELOPING THE OFFERING AS SERVICE: THE CSS (CONCEPTUALIZING, SYSTEMATIZING, SERVICIZING) MODEL

A manufacturer that has adopted a service business logic has to develop its processes so that they support the corresponding customer processes (compare Figure 16.2). Formulated in a generic way, a business mission based on a service logic could read as follows (in Chapter 3 guidelines for developing a service-oriented business mission were discussed; see Figure 3.5):

The firm’s mission is to support the customer’s production process (or whichever process is concerned) and related processes (logistics, installation, maintenance, payment and book-keeping, information need, etc. depending on what is included in the customer relationship) in a way that creates value-in-use24 for the customer, and moreover supports the customer’s business process and commercial outcomes.

Hence, the business mission should not be to supply customers with, for example, the best product, but instead to support the customer’s activities and processes in a value-creating manner. The difference between the two formulations is huge. The first one is based on a manufacturer’s traditional main knowledge base and core competence, whereas the latter is based on a service logic and the main knowledge base and core competence of a service business.

However, once the business mission is formulated in a service-oriented manner and the manufacturing firm starts operating as a service business, the firm’s offering has to be organized and developed as one continuous flow of support to the customer’s various processes over the customer lifecycle. It is important to realize that service is a process, and however much this process is planned and organized, it will never become anything like a standardized product. Therefore, an idea of a ‘product’ must never be the ideal goal of the development of an offering. Here a three-stage approach called the CSS model is helpful. CSS stands for:

Conceptualizing.

Systematizing.

Servicizing.

Conceptualizing means that the firm decides what kind of support it should provide a customer with, how value should be created in the customer’s processes, and how customer touchpoints should be handled and interactions with the customer’s various processes should function and what they should lead to in terms of support to the customer’s everyday activities and processes, and how this should affect the customer’s business process commercially. Conceptualizing includes decisions about what core solutions (for example, a product, services, information, combinations of such and other resources) should be offered and how, for example, logistical, repair and maintenance, educational, advisory, invoicing, problem-solving and other activities should function in order to support value-in-use for the customer over the customer lifecycle.

In short, conceptualizing is to determine what to do for the firm’s customers and how to do it.

Systematizing means that the firm should decide what kind of resources are needed in order to implement the conceptualized offering and create a structural way of putting in place the various processes of the offering. This is done so that resources are used in a rational way. Cost–benefit considerations should be taken into account in the systematizing phase. An objective with systematizing is to make sure the unnecessary or unnecessarily expensive resources are not used, or that resources are not used and processes developed in an unorganized and unco-ordinated way. Thegoaloforganizing resources and processes used is to achieve a maximal effect in terms of supporting the customers’ everyday activities and processes without creating unnecessary costs. The goal of co-ordinating resources and processes is to make sure that they are not functioning in ways that create information problems and confusion in the customer contacts and in the customer’s processes.

In the systematizing phase it is important to realize that standardized packages must not be created. The customer contacts over time are not standardized. Instead, it is a question of developing organized guidelines for performance where flexibility is allowed and encouraged. However, at the same time systematizing also includes setting the limits for flexibility.25 These limits are, of course, based on a cost–benefit analysis, however a long-term analysis of what it costs and what can be gained is required. Standardized modules that can be combined in different ways to achieve flexibility can, of course, be used, but this must not lead to stereotyped behaviour.

In short, systematizing is:

• To determine what resources and processes are needed for the firm to support customers’ activities and processes in a value-creating way.

• To organize resources and processes that constitute the offering.

• To co-ordinate the way various resources and processes function.

• To determine the limits for flexibility in the way resources and processes function based on a long-term cost–benefit analysis.

Servicizing is the final phase of the CSS model. Once the resources and processes and the organized and co-ordinated ways of using them have been determined and the limits for flexibility set, one has to make sure that the various processes and customer contacts indeed function in a value-supporting manner. The attitudes, knowledge and skills of people, the capabilities of physical resources, systems and infrastructures to function in a customer-focused way, and the customer-focused quality of the leadership provided by managers and supervisors have to be ensured. Sometimes customers have to be educated about how to participate in the processes. The goal is to develop all resources and processes supporting the customers’ everyday activities and processes, regardless of what these activities and processes are, in a way the guarantees that value-in-use is created in those processes. Value-in-use means that the customer perceives and wherever possible can calculate that its processes function more efficiently and effectively with the support of the supplier’s activities than without them or with the support of a competitor. In the previous section, servicizing was discussed in detail and the question of what can be servicized was addressed with examples (see Table 16.1).

In short, servicizing is to make sure that the planned offering including a set of resources, processes, and interactions functions in a value-supporting way, that is, functions as service for the firm’s customers, or to put it in another way, truly serves the customers.

The CSS model can often be used in two stages. First, a general conceptualizing, systematizing and servicizing of the offering to customers can be undertaken. The result is an offering that can be used as a general guideline for the business. In the next phase, if and when appropriate, applications geared towards specific customers can be created as guidelines for how a specific customer should be served.

OUTSOURCING AND BUILDING NETWORKS

Outsourcing has been mentioned a number of times throughout this book. Outsourcing (sometimes also called ‘offshoring’) means that a firm lets an external organization perform an activity. For example, call centres answering customers’ queries about a product or a service, deliveries of goods, maintenance of products and equipment delivered, and also sometimes product development and the development of software are frequently outsourced. Sometimes outsourcing takes the form of formal networks, but the difference between building networks and outsourcing is not always very distinct. For example, in the construction industry it is normal that firms build stable or loosely-coupled networks of subcontractors that take care of parts of the construction process. Firms in the clothing industry form networks with designers, manufacturers and distributors to develop a successful business.

When, for example, product development or design of clothing are outsourced, the outsourcing firm’s customers do not experience the performance and behaviour of network partners or the outsourced activities other than indirectly in the form of the final product or clothing. However, in service the situation is typically different. The way a call centre answers a call by a given firm’s customer and how well it manages to solve the customer’s problem have a direct impact on this customer’s perception of the outsourcer’s service and its quality. If the firm that handles an outsourced activity misbehaves and provides bad service, it is the outsourcing firm that suffers. This means that outsourcing must be managed carefully, and activities outsourced for the right reasons.

Today service activities are far too often outsourced for the wrong reasons. In Chapter 1 the difference between outside-in management and inside-out management was discussed (see also Figures 1.1 and 1.2). The former approach means that managers’ first focus on understanding the customers’ processes and the firm’s revenue-generating capability, and only then on the firm’s own processes and technologies and costs. The latter approach means that focus on costs and the firm’s processes dominate managerial decision-making, and revenue-generating implications and the customers’ processes are given less or even marginal attention, if any. Cleary, for outsourcing to be successful, the outsourced service activity should support the service quality goals. This means that the dominating reason for outsourcing, for example, call centre services or maintenance services, should be a strenuous effort to maintain the overall perceived quality of the firm’s offering, and thereby strengthen or at least maintain the firm’s revenue-generating capability. Of course, cost considerations should also be made, but not dominate. Outsourcing decisions should be guided by outside-in management considerations.

In reality, outsourcing decisions are often made from an inside-out management perspective. Cost considerations determine what is outsourced and how. The result is often low perceived quality, and unsatisfied customers. As a consequence, limited or no positive effect on the firm’s performance is achieved through outsourcing.26

In conclusion, outsourcing and forming networks to serve customers may be useful. However, for service businesses one must always remember that the outsourced service activity always has a direct impact on the customers’ perceptions of the outsourcing firm’s service quality, and on the firm’s brand fulfilment and image. Hence, outsourcing decisions must not be made based primarily on cost considerations. Instead, an outside-in management approach needs to be taken. Questions about how outsourcing a service activity to an outside firm or network partner will support the customers’ processes and strengthen the outsourcing firm’s revenue-generation capabilities must be asked and properly answered. Cost considerations are of course also important, but they must not dominate decision-making. An outsourcing decision which saves costs but hurts the firm’s capability to generate revenues is clearly not wise, and should not be accepted from a commercial point of view.

WHAT DOES TRANSFORMATION INTO A SERVICE BUSINESS COST?

‘What does it cost to transform a manufacturing firm into a service business?’ and ‘Does it cost considerably more to operate as a service business?’ are frequently asked questions. The transformation process may require some investments in internal marketing and employee education and in development of some organizational structures, but most of all it requires intellectual effort. What is required in the transformation process is the development of a business mission geared towards a service logic, renewed strategies and service-focused operational routines, where the resources and operational pro-cesses throughout the organization are used in a new way that supports the customers’ everyday processes and activities throughout their organizations. Moreover, organizational structures, leadership models, and planning and budgeting routines may have to be changed. Finally and above all, for a service culture to emerge attitudes have to be changed among everyone from top management throughout the organization. Provided that the business mission and strategies are renewed, the rest does not have to cost too much. However, if old manufacturing-oriented attitudes, missions and strategies remain, transformation attempts will start to become expensive and will probably not lead to any lasting changes.

When the transformation has taken place, operating as a service business does not imply a higher cost level. Normally the resources needed already existed before the transformation, and processes to take care of all necessary activities were in place. The investments that may be required are in transformation, not in operating as a service business. On the contrary, relationship costs for the supplier may decrease, and probably will do so.

NOTES

1. See Bowen, D.E. & Siehl, C., A framework for analyzing customer service orientation in manufacturing. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 1989, 75–95. For an overview of the early literature on this need, see Oliva, R. & Kallenberg, R., Managing the transition from products to services. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 14(2), 2003, 160–172.

2. Oliva & Kallenberg, op. cit., 165fi.

3. A notable exception is Grönroos, C. & Helle, P., Adopting a service logic in manufacturing: conceptual foundation and metrics for mutual value creation. Journal of Service Management, 21(5), 2010, 564–590. Typologies of service infusion strategies have been suggested in Raddats, C. & Kowalkowski, C., Reconceptualization of manufacturers’ service strategies. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 21(1), 2014, 19–34. In Kowalkowski, C, Kindström, D, Brashear Alejandro, T., Brege, S. & Biggemann, S., Service infusion as agile incrementalism in action. Journal of Business Research, 65(6), 2012, 765–772, the authors discuss service infusion and demonstrate problems with applying this concept.

4. See http://andyneely.blogspot.fi/2013/11/what-is-servitization.html. (18 March 2014).

5. See Grönroos & Helle, op. cit., and also Oliva & Kallenberg, op. cit., who make this observation in their four-phase model.

6. Fang, E., Palmatier, R.W. & Steenkamp, J-B.E.M., Effect of service transition on strategies and firm value. Journal of Marketing, 72(5), 2008, 1–14. See also Visnjíc Kastelli, I. & Van Looy, B., Servitization: disentangling the impact of service business model innovation on manufacturing firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 31(4), 2013, 169–180.

7. Dachs, B., Biege, S., Borowiecki, M, Lay, G., Jäger, A. & Schartinger, D., Servitisation of European manufacturing: evidence from a large scale database. The Service Industries Journal, 34(1), 2014, 5–23. This study also indicates that small and large firms may benefit more from servitization.

8. See Smith, L., Maull, R. & Ng, I.C.L., Servitization and operations management: a service-dominant logic approach. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 34(2), 2014, 242–269, who conclude from their research that becoming a service business is not based on a transition from one stage to another, but an evolutionary process towards a service-based mode of operations.

9. See Barnett, N.J., Parry, G. Saad, M., Newnes, L.B. & Gah, Y.M., Servitization: is a paradigm shift in the business model and service enterprise required? Strategic Change, 22(3-4), 2013, 145–156.

10. See Grönroos, C., Adopting a service logic for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 2006, 317–333.

11. See Grönroos & Helle, op. cit.

12. See Brax, S., A manufacturer becoming service provider – challenges and a paradox. Managing Service Quality, 15(2), 2005, 142–155.

13. Grönroos & Helle, op. cit. Bowen and Siehl were one of the first, if not the first, to discuss the need for manufacturers to transform their whole business into a service business. See Bowen & Siehl, op. cit.

14. From a customer point of view, every business is a service business and every firm a service firm. See Webster Jr., F.E., Executing the new marketing concept. Marketing Management, 3(1), 1994, 9–18 and Vargo, S.L. & Lusch, R.F., Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(Jan), 2004, 1–17. See also Grönroos & Helle, op. cit., and Eggert, A., Hogreve, J., Ulaga, W. & Muenkhoff, E., Revenue and profit implications of industrial service strategies. Journal of Service Research, 17(1), 2013, 23–39, where the authors demonstrate empirically that a service-led strategy in manufacturing firms may have a positive effect on revenues and profits.

15. For an interesting discussion about the conflicts between product and service businesses in a manufacturing context see Auguste, B.G., Harmon, E.P. & Pandit, V., The right service strategies for product companies. The McKinsey Quarterly, 1, 2006, 41–51.

16. See Auguste, Harmon & Pandit, op. cit.

17. This metaphor was used in Storbacka, K. & Lehtinen, J.R., Customer Relationship Management. Singapore: McGraw-Hill, 2001.

18. MacMillan, I.C. & McGrath, R.G., Discovering new points of differentiation. Harvard Business Review, Jul–Aug, 1997, 133–145.

19. MacMillan & McGrath, op. cit., 134–137, 143.

20. See, for example, Grönroos, C. & Ravald, A., Service business logic: implications for value creation and marketing. Journal of Service Management, 22(1), 2011, 5–22. See also Prahalad, C.K. & Ramaswamy, V., The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2004.

21. The technical value dimension has also been labelled ‘functional value dimension’. See Gupta, S. & Lehman, D.R., Managing Customers as Investments. Wharton School, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2005. However, in order to avoid confusion with the functional quality concept of the perceived service quality model, the expression ‘functional value’ is not used here.

22. See MacMillan & McGrath, op. cit., 144–145, who use gasoline sales as an example.

23. Compare Storbacka & Lehtinen, op. cit.

24. Value-in-use means that the customer perceives and wherever possible can calculate how its processes function more efficiently and effectively with the support of the supplier’s activities.

25. Here we can see the difference between systematizing and productizing, a commonly used concept in service businesses. Productizing views standardized products as the ideal and service as problems. It is a matter of creating packages and eliminating flexibility as much as possible. The goal is to create standardized products out of service processes. However, the processes do not disappear anywhere. Customer-oriented flexibility is the strength of service and it is important not to eliminate that. Therefore, productizing as a concept and a term idealizing the manufactured product concept is dangerous in a service business. It is dangerous for two reasons: it is based on an impossible thought that service processes through productizing would disappear and could be reduced to a standardized thing, a package equalling a manufactured product; and psychologically it makes managers and customer contact employees alike turn their backs on the customers and focus on stereotyped behaviour instead of listening to the customers. Productizing kills a service. However, productizing aims at an important issue, the need to create organized guidelines for how service should support customers’ activities and processes. The CSS (Conceptualizing, Systematizing, Servicizing) model is offered as a service-oriented alternative for achieving that goal.

26. See Gilley, K.M. & Rasheed, A., Making more by doing less: an analysis of outsourcing and its effects on firm performance. Journal of Management, 26(4), 2000, 763–790, where the authors did not find significant effects of outsourcing on firm performance. If there is an effect, it depends on the firm’s strategy and also on the environment.

REFERENCES

Auguste, B.G., Harmon, E.P. & Pandit, V. (2006) The right service strategies for product companies. The McKinsey Quarterly, 1, 41–51.

Barnett, N.J., Parry, G. Saad, M., Newnes, L.B. & Gah, Y.M. (2013) Servitization: is a paradigm shift in the business model and service enterprise required? Strategic Change, 22(3-4), 145–156.

Bowen, D.E. & Siehl, C., (1989) A framework for analyzing customer service orientation in manufacturing. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 75–95.

Brax, S. (2005) A manufacturer becoming service provider – challenges and a paradox. Managing Service Quality, 15(2), 142–155.

Dachs, B., Biege, S., Borowiecki, M, Lay, G., Jäger, A. & Schartinger, D. (2014) Servitisation of European manufacturing: evidence from a large scale database. The Service Industries Journal, 34(1), 5–23.

Eggert, A., Hogreve, J., Ulaga, W. & Muenkhoff, E. (2013) Revenue and profit implications of industrial service strategies. Journal of Service Research, 17(1), 23–39.

Fang, E., Palmatier, R.W. & Steenkamp, J-B.E.M. (2008) Effect of service transition on strategies and firm value. Journal of Marketing, 72(5), 1–14.

Gilley, K.M. & Rasheed, A. (2000) Making more by doing less: an analysis of outsourcing and its effects on firm performance. Journal of Management, 26(4), 763–790.

Grönroos, C. (2006) Adopting a service logic for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 317–333.

Grönroos, C. & Helle, P. (2010) Adopting a service logic in manufacturing: conceptual foundation and metrics for mutual value creation. Journal of Service Management, 21(5), 564–590.

Grönroos, C. & Ravald, A. (2011) Service business logic: implications for value creation and marketing. Journal of Service Management, 22(1), 5–22.

Gupta, S. & Lehman, D.R. (2005) Managing Customers as Investments. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School.

http://andyneely.blogspot.fi/2013/11/what-is-servitization.html.

Kowalkowski, C., Kindström, D., Brashear Alejandro, T., Brege, S. & Biggemann, S. (2012) Service infusion as agile incrementalism in action. Journal of Business Research, 65(6), 765–772.

MacMillan, I.C. & McGrath, R.G. (1997) Discovering new points of differentiation. Harvard Business Review, Jul–Aug, 133–145.

Oliva, R. & Kallenberg, R. (2003) Managing the transition from products to services. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 14(2), 160–172.

Prahalad, C.K. & Ramaswamy, V. (2004) The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Raddats, C. & Kowalkowski, C. (2014) Reconceptualization of manufacturers’ service strategies. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 21(1), 19-34.

Smith, L., Maull, R. & Ng, I.C.L. (2014) Servitization and operations management: a service-dominant logic approach. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 34(2), 242–269.

Storbacka, K. & Lehtinen, J.R. (2001) Customer Relationship Management. Singapore: McGraw-Hill.

Vargo, S.L. & Lusch, R.F. (2004) Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(Jan), 1–17.

Visnjíc Kastelli, I. & Van Looy, B. (2013) Servitization: disentangling the impact of service business model innovation on manufacturing firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 31(4), 169–180.

Webster Jr., F.E. (1994) Executing the new marketing concept. Marketing Management, 3(1), 9–18.