23. Bang & Olufsen: Modulating Strategic Renewal Through Innovation and Organizational Design

From an Incumbent Company’s Perspective

The history of Bang & Olufsen (B&O) started in Struer, a small village in the North of Denmark. In 1925 the two young engineers, Peter Bang and Svend Olufsen, pursued the dream of developing the perfect radio. Struggling in the first years to make a real profit, they did not falter in their determination—not even when saboteurs burnt down one of their early factories during World War II as they refused to collaborate with the Nazis. The persistence of the two young and undeterred engineers eventually paid off, and they built a company that evolved into an enterprise unanimously accepted as one of the hallmarks of Danish quality. B&O’s uncompromising attention to quality and design earned the company worldwide recognition and a spot in the permanent collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1972.

If success is hard to achieve, it is even harder to maintain; B&O faced several challenges on many fronts over decades, first from the low-price and high-volume Japanese products in the ‘70s, then by the economic downturn and loss of direction in the ‘80s, which brought the company to the brink of collapse.1 However, at the beginning of the ‘90s, B&O’s brand and profits began to shine again under the leadership of CEO Anders Knutsen and his vision “The best of both worlds: Bang & Olufsen, the unique combination of technological excellence and emotional appeal.” The re-establishment of B&O’s great design and technological innovation was championed new icons like the Beosound 9000, a music system that rapidly became one of the company’s most recognized products.2 The section below describes the recent history of B&O, together with the challenges and strategic choices that accompanied it.

1For more details on the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, see also Ravasi and Schultz (2006). For an encompassing history of B&O since the early days, see Bang (2005).

2For more details on the end of the ‘90’s and the first years of 2000s, see Austin and Beyersdorfer (2007).

Strategies

WOW: How to Continually Renew for Success in a Fast-Moving Industry?

For organizations like B&O, continuous strategic renewal is a key capability, in which the link between environmental change and corporate strategy is continuously modified over time. Closing the gap between the current core capabilities and the evolving base of competitive advantage, however, is a challenging process that clashes against the core norms and institutionalized practices of any organization. Renewal is only achieved through promoting, accommodating, and utilizing new knowledge and innovative behavior to refresh or replace the company’s tangible and intangible resources, to substantially affect its long-term prospects. A look into the history of B&O illustrates how they took up this challenge.

The Enduring History of B&O

The most recent chapter of B&O started in the early 2000 and challenged the now 90-year old company like never before. The rise of digital technology as the new paradigm affected all of B&O’s product lines. The market was stormed by companies like Apple or Google that still today are both competitors and partners and present throughout all levels of the value chain. Furthermore, the generational shift of B&O’s target customers from the “Baby boomers” to “Generation X” implied a completely new way of listening to music.

To meet up with the changing market, in 2001 new CEO Torben Ballegaard enhanced the product development process, leading to an increased production output and a reinforced position of recognized design and technological excellence. The production of Beolab 5 in 2003, employing the “acoustical lens technology,” achieved a new standard in technological excellence and triggered a partnership with Audi, which paved the road for the introduction of their new car stereo system. The brand kept on increasing its value, reaching a total turnover of DKK 4.38 billion in the financial year 2006 to 2007, and a peak in its operating profits of DKK 530 million.

However, the tide was about to turn. Following the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2008, the sales of luxury goods in the European market, 83 percent of B&O’s total turnover, were hit drastically. CEO Ballegaard was dismissed after a sharp 30 percent decline in turnover, and a 350 percent decline in profit3 in the financial year 2008–2009. Unprofitable explorative projects like the Serene mobile phone or ill-timed high-end products like the 103-inch plasma TV were indications of a troubled product pipeline. The underlying vulnerability was embodied by slow new product development process and problematic strategic direction, which largely failed to keep up with the convergence of digital technologies. B&O’s successful competences—crafting sculptural hardware while finely developing each product’s core from scratch—became a source of inertia and rigidity in developing the necessary capabilities for the new paradigm and in expanding the strategic horizon to effectively include and exploit them.

3Data from B&O annual reports.

In 2008, new CEO Karl “Kalle” Hvidt Nielsen improved the speed of product development by radically changing the technology strategy and developing technology platforms. This ensured shared development across products, thus decreasing complexities and development time.4 In 2009 Beosound 5, a music system that aims at creating one’s own digital library, was released as the first consistent attempt at digital technology—considerably later than the introduction of iPod and iTunes by Apple in 2001. Yet, despite stabilizing the company the company did not achieve growth under his guidance.

4Wheelwright and Clark (1992).

In 2011, the new CEO Tue Mantoni stepped in to shift the overly product-centric B&O toward becoming an international lifestyle brand, a move structured into a 6-year long strategy called Leaner, Faster, Stronger. Its key drivers have been a stronger customer-focused orientation and a clear re-focus on the core capabilities that have made the B&O brand strong: sound, design, and craftsmanship. “B&O Play,” the new product line for attracting younger customers was a first step in this direction, together with an increased focus on the profitable automotive business, the consolidation of the retail network by trimming off the least profitable shops, and an increased presence of B&O in BRIC countries.

As of the beginning of 2015, the new areas of business—Automotive and B&O Play—are growing strong and providing positive brand exposure through continuous awards of excellence. Sales per store increased, achieving overall profitability, supported by a complete product portfolio turnaround. The new generation of B&O’s products is championed by the wireless speaker series like Beolab 18 and the 4K TV Avant, followed by Beosound Moment, launched in January 2015. Despite the new launches however, the core product categories—Audio and Video—are still lacking the expected growth that was forecasted in the strategy.

How Is B&O a Positive Outlier?

A Look from Within

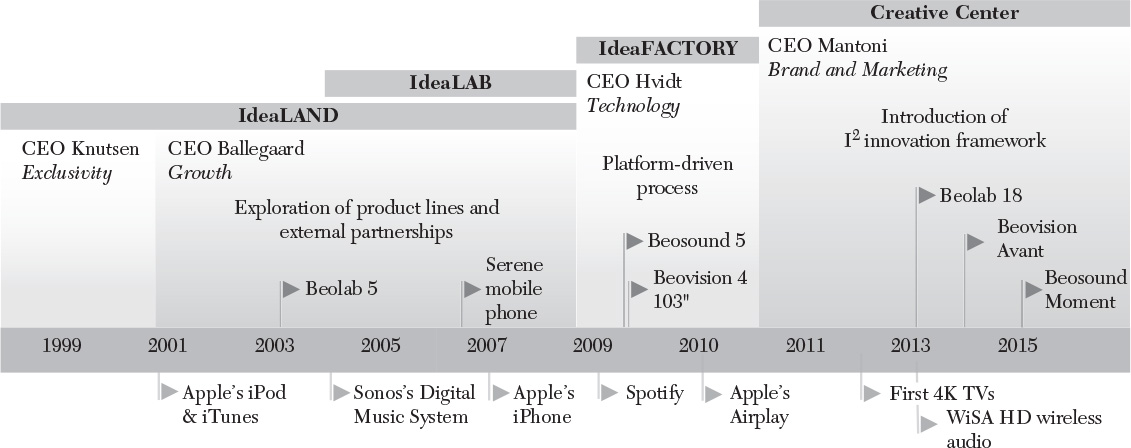

As Marie Schmidt (Vice president, Brand, Design & Marketing) noted, “If there is a place around the world where everyone is often convinced this product is his or her chance to create a masterpiece, that place has got to be B&O. Everybody knows about it, and everyone is proud about it.”5 The core essence of B&O can be defined as a delicate balance between meaning-driven6 (i.e., design and user experience) and technology-driven innovation, which needs to be synergistically integrated. Still, how B&O creates its products has changed over time. It has largely been affected by, and has itself affected the strategic direction of the company, as is summarized in Figure 23.1. Each phase is championed by a different CEO, and is characterized by the modification of the existing organizational design and the unit in charge of the innovation process.

5Interview on December 9, 2014.

6For meaning-driven innovation, see Norman and Verganti (2013); Verganti (2006).

In the so-called “IdeaLAND,” B&O’s concept developers linked a pool of highly skilled engineers to some of the world’s best designers, who are still today employed from outside the company so that they are not restrained by its dynamics and limitations. By relying on their understanding of the world, B&O delivered iconic products that would have been difficult to develop being bound to a standard technology-push approach. Designers were given total freedom of maneuvering when creating concepts and limited technological constraint, leading engineers to be constantly challenged by their often unique and extravagant ideas. In a predictable and fairly stable market, such approach allowed B&O to create a recipe for success—however, since the advent of the digital technology and players like Apple, Sonos, and Spotify, B&O has been challenged by a faster developing, more complex, and more design-conscious technology paradigm. In 2004, “IdeaLAB” was created to explore opportunities provided by the new landscape. The new unit was kept separate to avoid its immature projects being overruled. At the same time, they were put in situations of explicit conflict to emphasize B&O’s distinct process of continuous clashes between conflicting ideas by designers and engineers to reach an optimal synthesis.7 However, this worked only partially—on one hand, IdeaLAB took longer than expected to produce tangible results and thus justify its existence, on the other the product development process was clearly still dominated by the figures heading IdeaLAND. This led to a tendency to allocate more resources to IdeaLAND projects than to combined ideas and resulted in a series of either frozen or aborted projects. To tackle the problem, in 2008 CEO Hvidt Nielsen merged IdeaLAND with IdeaLAB to create the new “Idea Factory.” Initially reporting directly to the CEO, over the years the leadership of Idea Factory passed through a few top executives and a few restructuring processes before becoming the “Creative Centre,”8 reporting directly to the CEO again today.

7Austin and Beyersdorfer (2007) present this concept revamping the classic philosophical idea that a clash between competing ideas can lead to a superior idea as their synthesis.

8In February 2014, the Creative Centre (at the time brand, design, and concepting) absorbed the department of marketing to ensure a continuity in the value chain and was rebranded in today’s “Brand, Design, and Marketing.”

In 2014, the “Technology Centre” underwent restructuring as well. Tensions in the product development domain, which accompanied the partial relocation of production from Struer to the Czech Republic in 2006, and the subsequent undesired delays and quality issues,9 required a new COO—Stefan Persson—to take over and integrate R&D, Product Management, and Operations under his guidance.

9Press release No. 14.23, 22.12.2014.

With regard to the process of new product development, it was left to an informal sequence of interactions between designers, concept developers, and engineers until 2012. This process, while never formalized, became institutionalized, a norm the organization would fight to preserve. Realizing that such a process design left too many uncertainties and inefficiencies unsolved, the new top management launched a new framework to professionalize the process from idea creation to implementation, scrapping old ways. Despite some resistance, the unanimous recognition of the need for a faster and more efficient development process brought most of the people to formally align. The new innovation process, called “I2,” consisted of two blocks: one for the development of ideas and opportunities, and the other for execution and production.10 In 2014, an increased focus on ideation was signaled with two new processes: the first one connecting the most innovative people in the company through a series of workshops, to develop a set of creative ideas to be evaluated by top management. This led to the definition of many new opportunities, some of which are already positioned on the roadmap for development. The second process involved an internal idea management system supporting the opportunity process with an ongoing source of creativity—a larger base of skilled B&O employees—both in terms of product and process innovation. Besides the process of pure ideation, concepts at B&O are also created through the management of roadmaps, which could lead to either the improvement of an old product or the filling of a void in terms of features or revenues. However, the front-end of the new opportunity phase and the back-end of the execution phase are often felt to be distant from each other, leaving a gap of uncertainty for the implementation of the more explorative ideas. To fill such a gap, elements of new ideas are sometimes trimmed to land onto safer concepts, similar to how exploitation is often favored over exploration for its better-articulated propositions.11 Two activities increasingly support the innovation process by ensuring an assessment of feasibility and consistency of B&O’s competences. The first one advances members’ interaction from the “tough triangle” (creative, technology and business centers) to an earlier point in the conceptualization phase. The second involves a newly developed “maturity matrix” to assess each concept element of proposed briefs.

10Despite its focus on execution, the second block also includes a framing track for projects benefitting a larger product base, as well as an exploration track for concepts needing additional resources to be investigated.

11Crossan and Berdrow (2003).

What Next?

With regard to product development, the concept of success is still open for discussion. Projects of incremental nature, like the new wireless speaker series, are articulated by firm employees as the result of a successful process, respecting time and budget plans. On the other hand, projects involving unbalanced concepts and inefficient processes, like Beosound Moment, are praised for being radically innovative when hitting the market. For which product should B&O strive, and which process should support it? The current stage-gate system of I2 has worked fine for incremental innovation, but has proven inadequate for more radical projects. Radical innovation, despite its potential, requires more process flexibility, and should be measured differently than based on straight execution. Balancing the concept development in terms of early participation of the “tough triangle’s” members, as mentioned earlier, is increasingly being considered a potential solution that would not require the redefinition of the whole framework.12 Without renouncing the characteristic “initial spark of genius” from concept developers,13 a more comprehensive technology-market linkage process before entering the execution phase could anticipate and find solutions to uncertainties that today are discovered too late in the process. This could more effectively lead to a successful product development. Moreover, doing so would serve the purpose of consistently integrating the opportunities provided by in-house research and pioneering technologies like the current sound zones systems early in the process.14

12Also suggested by Dougherty (1992).

13Perhaps this is the spark from outliers the authors are referring to here.

14See Baykaner et al. (2015); Francombe, Mason, Dewhirst, and Bech (2015).

SO WHAT: Comparison with Other Companies (Incumbents and Adjacents)

When compared to the incumbent companies in the field (and many adjacents), what makes B&O stand out is its resilience and willingness to continuously challenge itself through a process of strategic renewal. There are three main lessons B&O can teach: the first involves strategic renewal and organizational design, in which the company adopts a new explicit strategy to be embraced by a newly established innovation unit. Today’s fast pace of industry developments emphasizes the act of balancing the exploitation of current business on one hand, and the creation of a competence base supporting exploration of new opportunities on the other. This cross-pressure is often embodied in such a new innovation unit, and can serve as a signal for change, especially for companies with mind-sets and culture strongly anchored in their previous successes. Failing to move on by resisting the renewal of the strategic direction, independent of its outcomes, is likely to result in a situation of complacency, which has led too many companies to fail.15

15See, e.g., the case of Polaroid by Tripsas (2013).

Secondly, B&O illustrates how organizational design affects the shifts in power and relationships among different groups involved in the innovation process, in this case, design and technology. Creative tension can be achieved across groups by acknowledging the other side’s expertise in a dynamic friendly fighting, or by overlapping knowledge domains with boundary spanning activities. The overpowering of one side (or individual) over the other might lead to a strong reliance on the former’s ability to synthesize them, leading to iconic products in lucky cases and to risky and unbalanced concepts in others.

The third lesson is to take strategy renewal to the innovation process, namely the process of translating a new vision into market-technology opportunities and subsequently crafting the resulting concepts into products. Despite the use of comprehensive frameworks defining roles and stages, the struggles in linking the various bits of the process and concretizing abstract visions into feasible projects make bridging activities by the individuals connected to the innovation process extremely valuable.

Challenges

As seen in the previous sections, B&O has faced several challenges over its 90-year history in the form of sabotage, competition, economic crisis, volatile market, quality issues, and many more. During these stages, B&O learned that many of these external contingencies could and should be overcome by adopting an encompassing process of strategic renewal, i.e., hitting the core product development process from the angles of strategy, organizational design, and innovation. Such processes however, often led to internal tensions related to the orchestrating and harmonizing strategy, organization design, and innovation processes, and to separate attempts to propose changes (design), to resist them (inertia), and, if any, to support them (entropy).16 Now, the critical challenge for B&O is to clearly frame the future direction of the company and move on from the past paradigms, both in terms of business model and operations. Moreover, while the balance of the creative and technology centers can be considered as the golden rule to B&O’s success, it is also the major source of inertia, together with tensions across managerial levels that often turn persistence into resistance from all sides.

16Oliver (1992).

The current competitive landscape of B&O puts an even stronger pressure for B&O to become Leaner, Faster, and Stronger. Bose and Harman are tough competitors in terms of sound quality and product selection, while Sonos is pushing B&O to include a comparable system of multi-channel and multi-room speakers in its portfolio. The hurdle for B&O is, with comparable resources, to compete on similar technical features and assortment while at the same time ensuring the integration of TVs and products from the Play line into the B&O system.

Such external and internal obstacles have seen the company struggling to deliver the expected growth. In June 2014, B&O issued additional shares worth 10 percent of the existing shared capital, aimed at raising resources for improving and strengthening sales and distribution channels, as well as maintaining the current level of investment in the continuous renewal of the product portfolio.17 Additionally, the second quarter of the financial year 2014–2015 saw B&O’s shares fall to the lowest level since 2009. In response to this challenge, Chairman Ole Andersen has announced that B&O would consider bid approaches by larger incumbents and adjacents, while CEO Mantoni announced the acquisition of B&O’s automotive division by Harman.18

17B&O Press release No. 14.02, 19.06.2014, Harman Press release 31.03.2015.

18Thomson Reuters, “Denmark’s Bang & Olufsen would listen to bid approaches.” http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/01/05/bang-olufsen-ma-idUSL6N0UK21X20150105 (accessed online January 15, 2015).

Outlook

B&O illustrates how the renewal of an organization needs to be considered through the relentless engagement of the triangle of strategy, organizational design, and innovation process. The current developments of market and technology make a continuous adaptation of the company’s capabilities necessary, yet increasingly complex. Companies’ strategies need to find their unique answer to the question of exploration and exploitation, and infuse clear direction even in daily activities. At the same time, companies should recognize that these activities could already embody partial answers to such questions, and hence should be embraced as part of the company’s future direction. Moving forward, like B&O is trying to do, is the only option. The open question is: Will the company be fast enough to generate the potential growth and re-establish themselves with a new wave of customers?

From the Perspective of Nicolai J. Foss, Professor of Strategy and Organization, Copenhagen Business School

Changing the Business Model of Bang & Olufsen

Cattaneo, Frederiksen, and Carugati (2015) provide a nice account of the strategic challenges of a company that while small in comparison to its huge competitors in the consumer electronics markets stands out on account of a long history of design-driven innovation that spans at least most of the nine decades of existence of the company. They make the reasonable point that choices related to overall strategic direction, innovation, and organizational design are strongly intertwined (or, “complementary”), which surely is a general proposition, but applies with perhaps particular force to B&O. The reason is that B&O is forced to find a new business model for its traditional video and audio products because of the increasingly strong competition from Internet-based services, and the likely decline of the traditional TV set.

Cattaneo et al. also seek to foster a discussion “about the existing models of strategic renewal,” based on how these fit with the case description. Specifically, they point to the importance of the organization of the innovation process in a company such as B&O that is entirely based on design-driven innovation, i.e., the notion that design is not about adding aesthetics to a product but at the very core of the product development process. This is an interesting point because discussion of internal organization tends to be sidelined in discussions of business model change (Foss and Saebi, 2015).

Bang & Olufsen: Icarus in Jutland?

Cattaneo et al.’s account is mainly focused on the B&O of the last decade. B&O suffered a major setback under the financial crisis of 2008–2009 (e.g., revenues dropped by 30+ percent), from which it has not yet recovered. Indeed, many commentators have argued, and Cattaneo et al. echo this, that B&O was, and still is, in the danger of falling victim to what Miller (1990) called the “Icarus Paradox,” i.e., the situation where a company fails massively and rather suddenly, after a long period of success—and the failure is brought about by the self-same reasons that drove success. The underlying drivers of the paradox are self-sufficiency, overconfidence, and complacency, an illusion of being (wholly) in control (e.g., neglecting technological change and competitor action), anchoring on too optimistic assumptions (about costs, sales, etc.) or misrepresenting these (to get projects accepted internally), and excessive specialization that introduce cognitive blinders that reduce flexibility.

Many such factors can be discerned in Cattaneo et al.’s account. For example, we learn of a “problematic strategic direction” which fails to keep up with digital developments in audio and video technologies and excessive focus on B&O’s core competence, the crafting of “sculptural hardware” in the context of a rock-bottom product development approach that emphasizes developing everything from scratch rather than relying on economies of scope across products and systems (p. 3). We similarly learn of overly targeting small, stagnant, and highly exclusive customer segments, and neglecting the markets that lie closer to consumer goods mass markets. In the light of such challenges, the new strategy (Bang & Olufsen, 2011) with its emphasis on lower-end markets, speedier and somewhat more formalized product development and improved customer focus, would seem to make much sense.

The Innovation Process in a Small Company

Of course, retrospective accounts easily falls prey to confirmation biases (e.g., Rosenzweig, 2007), i.e., the information looked for, presented, and discussed is driven by one hypothesis alone, to the neglect of rival hypotheses. Basic rival hypotheses are the financial crisis, changing consumer preferences (not everyone would agree that all B&O products are top-notch in the aesthetics/design dimension), difficulties of controlling internal costs and/or the distributor network, and internal conflicts and tensions (e.g., see Krause-Jensen’s [2010] account of the rise and fall of value-based management in B&O). Here is a brief attempt at a very simple alternative account of the troubles of B&O in recent years that centers on diseconomies in the innovation process.

Fundamentally, B&O is a tiny player in most of its markets, in particular, B2C markets, like consumer electronics, high-end consumer electronics, high-end audio systems, home luxury products, e.g., high-end furniture, etc. The exception is its position in the B2B market, where it was the dominant producer of exclusive sound systems for high-end cars (until the automotive division was divested in March 2015). In any case, the brand name value of B&O is arguably out of proportion compared to the size of the company (e.g., in terms of employees or sales; 2013 revenues of around 500 million USD is not a lot). Although a significant fraction of B&O employees are rather directly involved in the innovation process, the relatively small size of B&O places inherent limits on the number of trials in terms of new ideas, development efforts, and product launches that the company can perform.

To be sure, small size is not just a handicap from the point of view of innovation. In particular, it is easier to incentivize and motivate key innovation people in a small company and smallness also facilitates knowledge sharing and trust. Smallness may also mean close physical proximity between product development and production (as is the case in B&O). However, smallness may also impede innovation. One reason is that if the innovation process is mainly internal, access to external weak ties that can bring new insights and ideas is hampered, and the innovation process involves a relatively small number of internal ties. In fact, B&O has tried to handle this problem in a number of ways. Most importantly, many design services have been externally sourced. Thus, some of the fundamental design-breakthroughs have been supplied external designers, such as Jacob Jensen and David Lewis. Also, when B&O began to explore flat-screen TV technology, they did so by, among other things, arranging an ideas competition among nine designers from different parts of the world.

The deeper problem is arguably the small size of the company in combination with a rather sluggish product development process. In non-perfect capital markets, small size means fewer funds for explorative efforts. Companies seek to engage in innovation for a variety of reasons, but one has to do with the creation of real options that can produce flexibility when consumer/customer preferences and technologies change, often in ways that are far from predictable. However, creating such real options is costly, and small size therefore translates into creating few real options. Moreover, it seems likely that there are economies of scale in the process of creating real options, as larger firms typically control more technologies, and therefore can produce more combinations and recombinations of these technologies.

As a small, specialized company B&O is clearly disadvantaged in these respects. Moreover, B&O may be additionally disadvantaged because of what is often seen as a product development process that is both extremely ambitious and quite sluggish—and therefore costly. A number of B&O products (e.g., Beosound 9000) were initially “unmanufacturable” and took many years from concept to actual production. Betting on relatively few, very ambitious concepts that may take several years to commercialize is a risky strategy indeed in a market that moves fast and unpredictably, including those markets where B&O is present. Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose, and with only few bets, losses can have a heavy impact.

The current B&O Strategy (Bang & Olufsen, 2011) may be interpreted as trying to grapple with the issue of an innovation process that is not only ambitious, costly, and sluggish, but also forms a very large part of the cost base of the company. Thus, the ambition is to double, perhaps even triple, the current revenues within a few years to spread cost of innovation across more units. The means to do this is investing more in the core business, targeting new segments with higher potential sales (as represented in the B&O Play business unit), and strengthening sales channels (idem.). Part of the cost of these investments comes from the recent divestment of the highly successful B&O automotive business unit.

Coda

It is surely safest to pass judgment on the soundness of corporate strategy in a retrospective mode. However, the danger here is that one falls victim to the confirmation bias and present facts in a way that lend credence to only one interpretation. The claim here is not that this is what Cattaneo et al. are doing. Rather, the claim is that their case description and general information about B&O lend support to another interpretation, namely that B&O has faced difficulties because the small size of the company and the peculiar characteristics of its innovation process mean that it engages in “too little” exploration in the context of fast-moving markets and technologies and because its ambitious innovation process has also been associated with high costs.

Seen in this perspective, the emphasis of the current management on providing more structure around the B&O product development process, engaging the company more in external collaboration (Bang & Olufsen, 2011), and spreading costs of innovation across more units as volume is increased through more efficient sales channels make much sense. The potential danger is providing too much structure around the process, stifling development efforts.