24. Outlook for the Strategist

Toward Strategic Resilience: Learning from Strategic Novelty (or What Is About to Leap at You)

“Everybody always wants to know what’s next. I always say that what I can imagine is rather dull. What I can’t imagine is what excites me.”

—Arthur Schawlow, Stanford physicist and Nobel Laureate1

1A History of the OTL. Stanford University. http://otl.stanford.edu/about/about_history.html.

Strategists beware. In 2 years, this book and the world will look different. Some of the outliers here may have fallen by the wayside. Some might turn into incumbents (i.e., the major firms in their industry or form entirely new sectors). Take this book as a guide by which to sample strategic novelty—novelty that will keep on reinventing itself whilst causing disruption. As we’ve shown over in the preceding pages, the most successful outliers revitalize our world not only by experimenting with strategic novelty but also by amplifying its effects. Thus, the kinds of disruptions that are most powerful are the ones we do not expect. Not only do they surprise us, they take us by force. They leap on us.

Where does such a force come from? One of the researchers involved in this project, Lakshmi Nair, described the companies as follows.

“I think these are companies with a permeable flow of information and resources between themselves and the customers. They are creative in uncovering unmet customer needs and are open to feedback from the users/customers. They continuously revise their ideas in response to such feedback. They envision growing beyond their current base, into something bigger and more impactful in the market.”

Another researcher, Inês Peixoto, described her learnings as follows:

“These companies are not afraid of making themselves vulnerable: like launching in alpha stage and iterating on the fly, as MakieLab did, putting the novelty out there and see what people make of it. It can seem a little foolish to by-the-book advice. Yet, I find it interesting beyond the “fail early” or “fail fast” mantras. While exposing vulnerability bears risks in two extremes: from being ridiculed to being imitated very easily by more powerful incumbents, it can be used to reduce the risk of growing/evolving the business, by learning. These companies don’t ask for permission either. Beyond boldness, I relate this to harnessing resources—e.g., digital platforms for social interaction, either pre-existing or custom-made—in order to create value. As discussed in the Introduction, the Internet makes this possible.”

Emergent Outlier-Incumbent Arenas

Which areas (even 2 years from now) do we think will be most affected by the dynamics we illustrated in this book? Let’s look at the arena of outlier-incumbent interaction to situate the forces we outlined industry-wise. Our case studies point to three arenas in which outliers’ and incumbents’ knowledge processes, organizational structures, technology, business models, etc., interact with significant potential for transformative impact that can cascade beyond any single industry. These arenas are open manufacturing, participant architectures, and inclusive financing.

Innovation in manufacturing currently encompasses the digitization of manufacturing and technologies such as 3D printing, an increasingly inexpensive technology enabling small-scale, localized production activity. Open manufacturing is thus a term that indicates the transformation ongoing in production and logistics activities that take many of these activities out of a dedicated factory and cause them to eventually become much more distributed and diffused, under no central planning or decision authority. Thus, these new open manufacturing models bring in new participants, from individuals to organizations. In the process it also changes the production and creation of knowledge as well as the processes by which it is transferred. This is an arena ripe for incumbent-outlier collaboration.

Architecting such participant contribution is a theme that cuts across all emergent outliers yet deserves to be distinguished in its own right. From companies such as Kaggle where data scientists compete to solve difficult tasks, to BioCurious where laboratory members work with biotech, to Genomera where anyone can seek to improve their physical well-being by collaborating online; participating in organizational activity is radically changing. The participants—amateurs—are sometimes people with (occasionally double) PhD degrees or impassioned autodidacts both with fantastic community connections in part due to their shared activities. They build new ways of working which are better suited for people who have a passion for doing something, irrespective of the pay. Such an amateur, or a “lover of” something, influences management professionals by insinuating the need to develop new attitudes toward organizing. It may not be fruitful to think about how to capture value and tie the resources to the organizations contractually, but rather about how to make the organization—the architecture of contribution—as attractive as possible and thus no longer requiring conventional ties. The resulting participant contributions may be fleeting, yet important. Kaggle organizes competitions through which the best scientists are recognized. BioCurious maintains a laboratory that members can use for doing whatever they are interested in. Strategically this means that emergent technologies are less noteworthy for what they enable in terms of new content of offering, but more so for how they make the offering possible, and how the people producing the new possibilities participate in their making and consumption. It is the organization of technology that enables people that matters. Resources are becoming increasingly mutable. Managers of incumbent companies need new organizing tools and managerial attitudes2 to collaborate with these outliers.

2G. Sevon and Liisa Välikangas: Strategies of Detachment—Of Mutable Resources and Late Modernity, Paper presented at EGOS Colloquium, July 5–7, 2012, Helsinki, Finland.

A third arena in which outlier knowledge models appear to be having industry-crossing repercussions is the theme of inclusiveness, particularly in financing. New models are extending financing to wider numbers of participants and organizations and, in doing so, are “democratizing finance” and shifting the channels for entrepreneurial competence flows, for example. This change will benefit from inclusive finance in the sense that capital, not just financial but also sweat equity and knowledge, will become much more available, transferable, and be governed by different rules and conditions compared to the previously dominant funding logics. Such shifts will not only result in a relative change of power positions in different industries (lessening the role of traditional banks, for instance) and societal arenas (with many new non-profits becoming players) but also alter underlying knowledge flows. Many established financial veteran companies are already vested in the opportunity frontiers that outlier finance firms are opening up in, for example, crowdfunding. Other firms will also benefit in broader funding for innovation, most importantly in expanding the range of innovation that attracts funding. Grow VC Group is an example of a firm funding innovation beyond the relatively few start-ups of interest to venture capitalists. Such new funding models are radically enlarging opportunities for financing innovation across the world beyond the small fraction that venture capitalists are interested in.

Strategic Resilience, or Learning from Things That Have Not Yet Happened

This book has important leadership implications in leveraging novelty. We call for strategic resilience. Being able to anticipate and adapt to change before a crisis forces a company into a painful reckoning is the hallmark of strategic resilience (Hamel and Välikangas, 2003; Välikangas, 2010). Such proactivity requires that a company and its leadership are able to learn from things that have not yet happened, in other words, from the peeks behind the curtain of the future that is embodied by outliers. These opportunity horizons that outliers point to may take a year or 10 to materialize but eventually many of these ideas will, through some outlet, become the mainstream. By then, those strategically resilient have made full use of the potential while the rest of the incumbents are still trying to make sense of the disruption at hand (see Figure 24.1).

Strategic resilience is the ability to undergo such ongoing change without having to resort to the production of great urgency—how many times a year can you evoke a “burning platform” or a must-win battle—or call for a crisis before people will burn out? A true crisis will bring its own change, and hence leaders who resort to such crisis tactics have abandoned leadership to the force of inevitability. Crises are also, by definition, not very manageable and may result in outcomes that may not be strategically desirable. Creative destruction then makes outliers into incumbents, until the next crisis arises.

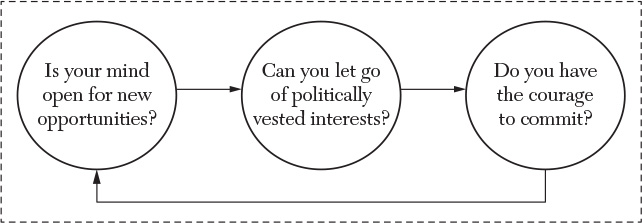

The first key to strategic resilience is the ability to have the cognitive flexibility to constantly assess the strategic novelty horizon such as described here and accept the challenge and uncertainty it proposes. The acceptance may mean incrementally experimenting with the implications of the new and adopt new ways of business while there is still time to learn from the outliers. Most importantly, such acceptance calls for the abandonment of unnecessary nostalgia for the tired past while mustering the courage to take up the new. The company mission may remain but the form by which the mission is implemented and executed that must be renewed.

The second key to strategic resilience is political. The pursuit of novelty requires the vesting of power from those that for reasons of self-preservation may resist renewal. It is very important to distinguish between resistance to novelty that is caused by a lack of courage to move on and the kind of resistance that may be justifiable—it may indeed be too early to make the big leap. A good test is this willingness to de-risk the effort and embark on related discovery and experimentation. An upfront dismissal often indicates that a person’s own interests are put ahead of those of the organization’s. Occasionally such resistance may simply be a matter of not caring or laziness—it is easy to keep doing what has been done in the past. Then it is even more important to infuse the organization with positive energy and commitment to the future.

The third key to strategic resilience is moving beyond the experimentation phase that does not yet require commitment to a transformation. If such a commitment continues to be postponed due to “not enough” evidence or information, or the opportunity horizon is always too far out to make the leap, these are signs of a lack of strategic resilience. The inevitable crisis will then eventually force the situation. To maintain strategic resilience capability, the organization ought to rehearse changing regularly, change even when it is not absolutely necessary, just to stay in shape. Organizations are a lot like people that inhabit them in that if the change is not exercised, the capability is lost. The change muscles decay and lose their mass. Strategic resilience means that change by crisis will never be necessary. However, if this capability has never been created, rehearsed, nor tested, as one executive puts it: “When the tiger is on your tail, it is too late to learn to run.” By then those who are strategically resilient have already spurted away, having long since leveraged the lessons from “things that have not yet happened.”