8.2. Model Development Process

There is clearly more to the global oil system than a simple balancing loop with delay. To gain more insight into the structure of the industry the project team (10 people in all) came together to share their knowledge about oil companies, oil producing nations and motives for investment and production. The team met three times for working sessions lasting three hours each. The meetings were facilitated by an experienced system dynamics modeller. One member of the team kept detailed minutes of the meetings (including copies of flip-chart notes and diagrams) in order to preserve a permanent trace of the model's conceptualisation. A sub-group of the project team met separately to develop and test a full-blown algebraic model.

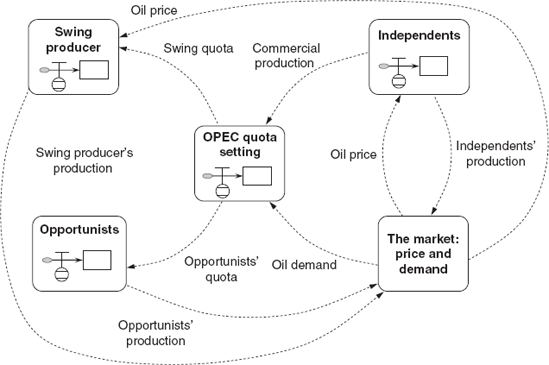

Figure 8.3. Overview of global oil producers

Figure 8.3 shows the resulting overview of global oil producers comprising five main sectors. On the right are the independent producers making commercial investment decisions in response to the needs of the market and oil consumers. On the left are the swing producer and the opportunists that make up the oil producers' organisation OPEC. This powerful group of producers has access to very large reserves of low-cost oil. Their production decisions are motivated principally by political and social pressures, in contrast to the commercial logic of the independents. They coordinate production through quota setting. The opportunists agree to abide by quota, but will sometimes cheat by producing above quota in order to secure more oil revenues. The combined output of all three producer groups supplies the market where both price and demand are set.

Price responds to imbalances in supply and demand and then feeds back to influence both demand and the behaviour of producers.

Now consider, in broad terms, how these five sectors are linked. In a purely commercial oil world there are only two sectors: the independents and the market. The market establishes the oil price and also consumers' demand for oil at the prevailing price. The oil price drives independents' investment and, eventually, leads to a change in production, which then feeds back to the market. The closed loop connecting the two sectors is none other than the balancing loop with delay mentioned earlier.

OPEC's involvement begins with quota setting. The nations of OPEC must collectively decide on an appropriate production quota. They do this by monitoring oil demand from the market and subtracting their estimate of independents' production. This difference is known as the call on OPEC and is the benchmark relative to which overall quota is set. The agreed quota is then allocated among member states. A portion called the swing quota goes to the swing producer and the rest to the opportunists. If OPEC is unified then all members follow quota, with the exception of the swing producer who makes tactical adjustments to production to ensure that oil price remains close to OPEC's target. In order to control oil price, the swing producer must closely monitor oil price and demand. Production from both the swing producer and opportunists then feeds back to the market, thereby completing the supply loop. As we shall see later there is much additional detail within each sector. For now, however, there is enough: five sectors and nine connecting lines to begin representing the rich and complex feedback structure of the global oil industry.

Why these five sectors? Why not lots more? Of course there is no one correct or best way to represent the industry. In reality, there are hundreds of companies and dozens of nations engaged in oil exploration and production. The project team was well aware of this detail complexity, but through experience had learned useful ways of simplifying the detail. In this case, the team agreed a unique conceptualisation of industry supply that focuses attention on the internal structure and political pressures governing a producers' organisation (OPEC) and its commercial rivals.

Models that fit the needs of executives and scenario planners do not have to be accurate predictive models. They should, however, have the capability to stimulate novel thinking about future business options. Moreover, models that are used to construct consistent stories about alternative futures need to be understood by the story writers (often senior planners) in order to be communicated effectively to corporate executives and business unit managers. A black-box predictor will not lead to the desired result, even if it has a good record of predictive power. These criteria help explain the style of modelling adopted – the need for a comparatively simple model, the relatively closed process (the project did not make direct use of other world oil market models or enlist the aid of world oil market experts as consultants) and the intense participation of senior planners in model conceptualisation. The project was not intended as an exercise in developing another general model of the oil trade to forecast better. The project team wanted to model their understanding of the oil market. Within the group, there was an enormous amount of experience, reflecting knowledge about the actors in the oil market and observations about market behaviour. But the knowledge was scattered and anecdotal, and therefore not very operational. The group also recognised that the interlinkages in the system were complex. The desire of the group was to engage in a joint process through which their knowledge could be pooled in a shared model and used to interpret real events. Most of the group members were not professional modellers. Other existing energy models to them were non-transparent black boxes, useful as a reflection of other's views, but quite unsuitable for framing their own knowledge.

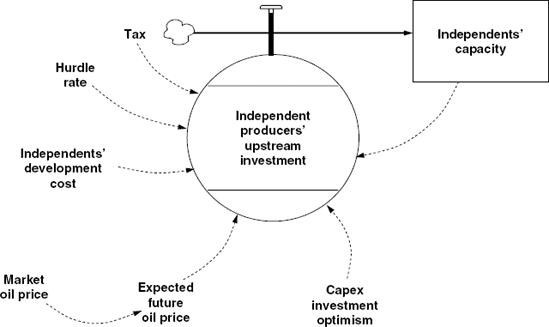

Figure 8.4. Independents' upstream investment