40 • Supply Chain Risk Management: An Emerging Discipline

SCRM Adoption

We know that leading- edge companies are much more likely to integrate

and align risk with corporate goals. ey generally have more visibility

into their organization as they are substantially more likely to perform

“what- if” scenario- planning and change analysis. On average, leaders

achieve almost 95% better accuracy of cash ow forecasts, which is clearly

better than what their peers achieve. And they tend to mitigate their nan-

cial losses down to 3% of revenue as opposed to their peers, who average

10% of revenue due to nancial loss. What characterizes early adopters,

industry average, and laggards?

Early Adopter Companies. Early adopters leverage their ERM tools

and technology to enhance the integration of risk management across the

business. ey continually link risk management to company goals and

compensation. And, they are improving visibility and monitoring of Key

Risk Indicators with new business analytic tools.

Early adopters also implement processes that are aligned with risk man-

agement and compliance, build a risk awareness culture throughout the

organization, and secure executive commitment for risk management ini-

tiatives. ese practices are being driven by the early adopters by a factor

of two- or three- to- one above the industry average and laggard companies.

Other attributes characterize early adopters. ese companies maintain a

senior management champion of risk, segment risk duties, cross- functionally

coordinate risk management, establish roles and responsibilities to execute

risk, and establish a risk committee to oversee key risks. ese commit-

ments by early adopters eclipse the industry average and laggards again by

a factor of two- or three- to- one.

Industry Average Companies. Average companies attempt a standard-

ized approach to communication and organizational collaboration rela-

tive to risk. Some of these companies are beginning to integrate and align

risk with corporate goals. Some are also developing and measuring risk

and performance. Several are beginning to improve the time- to- decision

by optimizing risk knowledge management activities and expanding risk

visibility throughout the organization. Senior management oversight and

engagement associated with risk to improve executive buy- in is starting to

occur at this level.

Laggard Companies. Laggards talk about supply chain risk but do not

fund projects to prepare for and respond to risk events at any real level.

Most have someone in the CFO’s oce reviewing enterprise risk in the

Supply Chain Risk Management: e As-Is Landscape • 41

classical nancial terms, such as hazard, nancial, and strategic risk. e

average operational and supply chain professional does not maintain sce-

nario game plans for risk events; therefore, SCRM is an event- driven, ad

hoc, or part- time experience. Most executives in this category assume

incorrectly that their people will know what to do in a risk event.

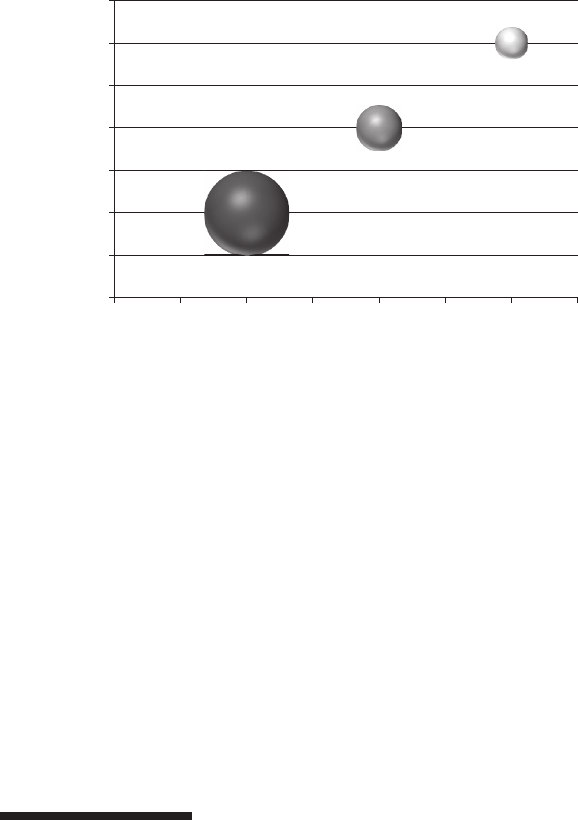

Figure2.4 depicts a graph encompassing laggards, industry average, and

early adopter companies in terms of the adoption rate of SCRM concepts.

In terms of the as- is state, it is safe to conclude that a majority of compa-

nies are still considered laggards in terms of their SCRM capabilities. is

suggests that we have more work to do to move companies away from the

laggard status. Subsequent chapters will concentrate on how to do that.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

e purpose of this chapter is to help us understand the current state of

supply chain risk management. From our analysis we can reach some over-

arching conclusions. First, the negative outcomes from supply chain risk

events are oen quite severe. Only a fool would believe otherwise. Second,

no consensus exists among companies or industries concerning how

to organize for or manage supply chain risks. e ways that companies

approach SCRM are varied. ird, most companies are ill- prepared from

Laggards, 70%

of Sample Size

Average, 20% of

Sample Size

Early Adopters,

10% of Sample Size

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

0 0.511.5 2 2.5 3

3.5

Maturity Level – Low to High

Adoption Rate – Low to High

FIGURE 2.4

SCRM adoption.

42 • Supply Chain Risk Management: An Emerging Discipline

an employee, measurement, organizational, and IT perspective to operate

in an environment characterized by increased uncertainty and volatility.

Another major conclusion is that most companies recognize the threat

of supply chain uncertainty and understand that operating in a condition

called the “new normal” will not be as enjoyable as operating in the “old

normal.” A study by Zurich Insurance, for example, reported that 75% of

respondents state they still do not have full visibility into their supplier

base. is is concerning because several studies have concluded that sup-

ply disruptions are the most widely cited supply chain risk event.

Finally, most SCRM eorts rely on heroics rather than planning and pre-

vention. In terms of SCRM maturity, most companies are considered lag-

gards with some movement toward average. Minimal proactive supply chain

risk management appears to be occurring. Growth along the maturity curve

needs to accelerate, especially when we consider that almost 75% of risk

managers believe that supply chain risk levels are higher than just a few years

ago and that risk will continue to increase. More than 70% of risk manag-

ers say the nancial impact of supply chain disruptions has also increased

compared with just a few years ago.

11

As a sign of the times, the Allianz Risk

Barometer in 2013 ranked for the rst time ever business interruption and

supply chain risks as the top concerns of businesses globally. One of the main

objectives of this book is to prepare us to manage in this “new (ab)normal.”

Summary of Key Points

• Most supply chain executives became interested in SCRM aer the

nancial meltdown of 2008. For many, 2008 was the genesis of their

risk management eorts.

• In 2009, the ISO Group delivered its rst set of standards directly

relating to supply chain risk, which was a major recognition of the

importance of SCRM. ese standards include ISO 73 and ISO 31000.

• e Supply Chain Risk Assessment Tool encompasses about 100

questions- of- discovery about a company’s supply chain across

10 tenets covering the entire supply chain. e basic premise is that

as the supply chain matures, the inherent risks faced by that supply

chain diminish.

• e new normal of global supply chains features more global sourc-

ing and manufacturing, hyper- demand requirements, longer supply

chain lead times, more potential points of failure, and managing

supply chains in far- ung corners of the world.

Supply Chain Risk Management: e As-Is Landscape • 43

• Over a period of several years, Zurich found that 85% of organiza-

tions experienced at least one supply chain incident that caused dis-

ruption to their business.

• e Risk Maturity Index suggests that companies with the highest

level of risk maturity experience 50% lower stock price volatility

than less- developed counterparts.

• e Four Pillars of SCRM are supply risk, process risk, demand risk,

and environmental risk. e supply pillar is by far the most mature

of the four because procurement professionals have been dealing

with supplier uncertainty and risk for over 50years. e demand

pillar ranks second in terms of maturity, followed by the process pil-

lar and nally the environmental pillar.

• SCRM Adoption utilizes a categorization scheme revolving around

laggards, industry average, and early adopters. In terms of the as- is

state, it is safe to conclude that a majority of companies are still con-

sidered laggards in terms of their SCRM capabilities.

ENDNOTES

1. “Managing Risk for High Performance in Extraordinary Times.” Accenture 2009

Global Management Study. 2009.

2. Arntzen, Dr. Bruce, Prof. Maria Jesus Saenz, and Isabel Agudelo. “e SCALE,

Supply Chain & Logistics Excellence Network.” MIT’s Global Scale Risk Initiative,

MIT’s Center for Transportation & Logistics, March 2010.

3. Accessed from Aberdeen Group CPO Survey Report & SCRM Report, 2010.

4. Burson, Patrick. “PRTM’s Global Supply Chain Trends 2010–2012 Survey.” Supply

Chain Management Review, (June 2010).

5. Pearson, Mark. “Inoculate against Supply Chain Risk.” Logistics Management, April

2011: 20–21.

6. Lee, Hau, PhD, and Kevin O’Marah. “Chief Supply Chain Ocer Report.” SCM

World, October 2011.

7. Pettit, Timothy J., Joseph Fiskel, PhD, and Keely L. Croxton, PhD. “Can You Measure

Your Supply Chain Resilience?” Supply Chain and Logistics Journal, Canada,

Spring 2008.

8. Catellina, Nick, and William Jan. “Leveraging Risk- adjusted Strategies to Enable

Corporate Accuracy.” Adapted from Aberdeen Group, April 2012.

9. Accessed from Zurich Re’s Knowledge Vault on Risk, July 2012.

10. Sodhi, Manmohan S., Byung- Gak Son, and Christopher S. Tang. “Researcher’s

Perspective on Supply Chain Risk Management.” Production and Operations

Management, (2011), Accessed from Jan Husdal’s SCRM blog (www.husdal.com).

11. Favre, Donovan, and John McCreery, “Coming to Grips with Supplier Risk.” Supply

Chain Management Review, 12, 6 (September 2008): 26. Citing statistics from Marsh,

Inc. and Risk & Insurance magazine.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.