3

Behavioral Dimensions of Charismatic Leadership

Jay A. Conger

Rabindra N. Kanungo

Charismatic leadership is a very rich and complex social phenomenon, and its manifestation among different kinds of leaders and its overpowering effects on followers have lent it an elusive and mystical character. Yet, in spite of its complexity, its effects are widely recognized. For example, it is not uncommon to hear members of an organization describe a leader as charismatic or attribute their motivation to a leader's charisma. It would seem that most of us carry in our heads a naive theory of what charisma really is. However, a more precise and scientific understanding of charisma remains to be developed. Social scientists have shied away from studying charisma's seemingly mysterious and impressionistic qualities. As research has moved toward greater methodological rigor and control, behavioral scientists have been attracted to phenomena that they could quantify and test under controllable conditions. They have moved away from the more subjectively complex topics that are difficult to quantify or replicate in laboratory or field experiments. Charisma's complexity has led to its neglect as a subject worthy of scientific study.

If we are to develop a deeper understanding of this complex phenomenon, it is important that we begin to strip this impression of mysticism from charisma. Charismatic leadership, like any other type of leadership, should be considered an observable behavioral process that can be described and analyzed in terms of a formal model. With this in mind, we will describe a conceptual framework that will assist researchers and practitioners in coming to grips with this elusive phenomenon.

The model we present builds on the idea that charismatic leadership is an attribution based on followers' perceptions of their leader's behavior. For example, most social psychological theories consider leadership to be a by-product of interaction between members of a group (Yukl, 1981). As members work together to attain group objectives, they begin to realize their status in the group as either a leader or a follower. This realization is based on observations of the influence process within the group helping members to determine their status. The individual who exerts maximum influence over other members is perceived to be playing the leader role. Leadership is then consensually validated when the membership recognizes and identifies the leader on the basis of their interaction with that person. In other words, leadership qualities are attributed to an individual when group members accept and submit to that individual's influence.

Charismatic leadership is no exception to this process. Thus, charisma must be viewed as an attribution made by followers. The roles played by a person make that individual (in the eyes of followers) not only a task leader or a social leader and a participative or directive leader but also a charismatic or noncharismatic leader. The leader's observed behavior can be interpreted by his or her followers as expressions of charismatic qualities. Such qualities are seen as part of the leader's inner disposition or personal style of interacting with followers. These dispositional attributes are inferred from the leader's observed behavior in the same way as other styles of leadership that have been identified previously (Blake and Mouton, 1964; Fiedler, 1967; Hersey and Blanchard, 1977). In this sense, charisma can be considered an additional inferred dimension of leadership behavior. As such, it should be subjected to the same empirical and behavioral analysis as participative, task, or social dimensions of leadership.

The Behavioral Dimensions of Charisma

If a follower's attribution of charisma depends on the observed behavior of the leader, what are the behavioral components responsible for such an attribution? Can these components be identified and operationalized so that we may understand the nature of charisma among organizational leaders? In the following sections, we describe what we hypothesize to be the essential and distinguishable behavioral components of charismatic leadership. We also hypothesize that these behaviors are interrelated and that the presence and intensity of these characteristics are expressed in varying degrees among different charismatic leaders.

To begin, we can best frame and distinguish these components by examining leadership as a process that involves moving organizational members from an existing present state toward some future state. This dynamic might also be described as a movement away from the status quo toward the achievement of desired longer-term goals.

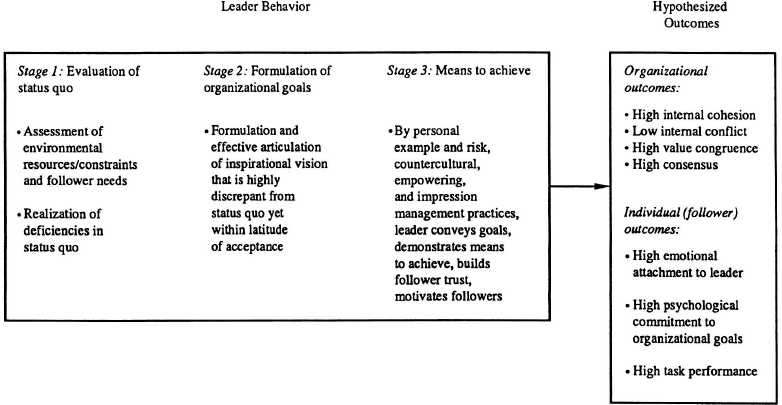

This process can be conceptualized into three specific stages (see Figure 1). In the initial stage, the leader must evaluate the existing situation or status quo. Before devising appropriate organizational goals, he or she must assess what resources are available and what constraints stand in the way of realizing future goals. As well, the leader must assess the needs and level of satisfaction experienced by followers. This evaluation leads to a second stage: the actual formulation and conveyance of goals. Finally, in stage three, the leader demonstrates how these goals can be achieved by the organization. It is along these three stages that we can identify behavioral components unique to charismatic leaders.

A caveat is in order. In reality, these stages do not follow such a simple linear flow. Instead, most organizations face ever changing environments, and their leadership must constantly be revising existing goals and tactics in response to unexpected opportunities or other environmental changes. This model, however, nicely simplifies this dynamic process and allows us to more effectively contrast the differences between charismatic and noncharismatic leadership. As such, the reader should keep in mind that, in reality, a leader is constantly moving back and forth between these stages.

Figure 1. The Charismatic Leadership Influence Process.

Specifically, we can distinguish charismatic leaders from noncharismatic leaders in stage one by their sensitivity to environmental constraints and follower needs and by their ability to identify deficiencies in the status quo. In stage two, it is their formulation of an idealized future vision and their extensive use of articulation and impression management skills that set them apart from other leaders. Finally, in stage three, it is their deployment of innovative and unconventional means for achieving their vision and their use of personal power to influence followers that are distinguishing characteristics. Figure 1 highlights these essential differences. The role of each of these behavioral criteria in the development of charisma is discussed in the sections that follow.

Stage One: Charisma and Sensitivity to the Environmental Context

Leaders of organizations have to be highly sensitive to both the social and the physical environments in which they operate. When a leader fails to assess properly constraints in the environment or the availability of resources, his or her strategies and actions may fail to achieve organizational objectives. Then he or she, in turn, is labeled ineffective. For this reason, it is important that leaders be able to make realistic assessments of the environmental constraints and resources needed to bring about change within their organizations. This is where the knowledge, experience, and expertise of the leader become critical. A leader must also be sensitive to both the abilities and the emotional needs of followers—who are the most important resources for attaining organizational goals. As Kenny and Zacarro (1983) point out, “persons who are consistently cast in the leadership role possess the ability to perceive and predict variations in group situations and pattern their own approaches accordingly. Such leaders are highly competent in reading the needs of their constituencies and altering their behaviors to more effectively respond to these needs” (p. 683).

Such assessments, while not a distinguishing feature of charismatic leaders, are nonetheless particularly important for these leaders because they often assume high risks by advocating radical changes. Their assessment of environmental resources and constraints then becomes extremely important before planning courses of action. Thus, instead of launching a course of action as soon as a vision is formulated, a leader's environmental assessment may dictate that he or she prepare the ground and wait for an appropriate time and place, and/or the availability of resources. It is presumed that many a time charisma has faded due to a lack of sensitivity for the environmental context.

In the assessment stage, what distinguishes charismatic from noncharismatic leaders is the charismatic leaders' ability to recognize deficiencies in the present system. In other words, they actively search out existing or potential shortcomings in the status quo. For example, the failure of a firm to exploit new technologies or new markets might be highlighted as a strategic or tactical opportunity by a charismatic. In other words, deficiencies in a firm's strategic objectives are more readily detected by the charismatic leader. Likewise, a charismatic entrepreneur might more readily perceive marketplace needs and transform them into opportunities for new products or services. In addition, internal organizational deficiencies may be perceived by the charismatic leader as platforms for advocating radical change.

Thus, any context that triggers a need for a major change and/or presents unexploited market opportunities is relevant for the emergence of a charismatic leader. In some cases, contextual factors are so overwhelmingly in favor of a change that leaders take advantage of them by advocating radical changes for the system. For example, when an organization is dysfunctional or when it faces crisis, leaders may find it to their advantage to advocate radical changes, thereby increasing the probability of fostering a charismatic image for themselves.

During periods of relative tranquillity, charismatic leaders may play a major role in fostering the need for change by creating deficiencies or exaggerating existing minor ones. They may also anticipate future changes and induce supportive conditions. In any case, context must be viewed as a precipitating factor, sometimes facilitating the emergence of certain behaviors in a leader that form the basis of his or her charisma. As Willner (1984) points out with regard to political leadership, “preconditions of exogenous social crisis and psychic distress are conducive to the emergence of charismatic political leadership, but they are not necessary…. If we extend the notion of crisis to include those largely generated by the actions of the leader, greater weight can be attached to crisis as an explanatory factor” (p. 52).

Because of their emphasis on deficiencies in the system and their high levels of intolerance for them, charismatic leaders are always seen as organizational reformers or entrepreneurs. In other words, they act as agents of innovative and radical change. However, the attribution of charisma is dependent not on the outcome of change but simply on the actions taken to bring about change or reform.

From the perspective of managing and fostering change, charismatic leaders then must be distinguished from administrators and other leaders (Zaleznik, 1977). Administrators generally act as caretakers who are responsible for the maintenance of the status quo. They influence others through the power of their positions as sanctioned by the organization. As such, they have little interest in significant organizational change. Noncharismatic leaders, as opposed to administrators, can be seen as change agents who may direct or nudge their followers toward established and more traditional goals. While they may advocate change, it is usually incremental and within the bounds of the status quo. Charismatic leaders, however, seek radical reforms for the achievement of their idealized goals and transform their followers (instead of directing or nudging them). Charisma, then, can never be perceived either in an administrator (caretaker) role or in a leadership role designed only to nudge the system.

Stage Two: Charisma and the Future Vision

Formulating the Vision. After assessing the environment, a leader will formulate goals for achieving the organization's objectives. Charismatic leaders can be distinguished from others by the nature of their goals and by the manner in which they articulate them. As the literature suggests, charismatic leaders are often characterized by a sense of strategic vision (Bass, 1985; Berlew, 1974; Conger, 1985; Dow, 1969; House, 1977; Marcus, 1961; Willner, 1984; Zaleznik and Kets de Vries, 1975). Here the word vision refers to some idealized goal that the leader wants the organization to achieve in the future. We hypothesize that the nature, formulation, articulation, and means for achievement of this goal proposed by the charismatic leader can be distinguished from those advocated by other types of leaders.

The more idealized or utopian the future goal advocated by the leader, the more discrepant it becomes in relation to the status quo. And the greater the discrepancy of the goal from the status quo, the more likely is the attribution that the leader has extraordinary vision, not just an ordinary goal. Moreover, by presenting a very discrepant and idealized goal to followers, a leader provides a sense of challenge and a motivating force for change. If we turn to the attitude change literature, it is suggested that a maximum discrepant position within the latitude of acceptance puts the greatest amount of pressure on followers to change their attitudes (Hovland and Pritzker, 1957; Petty and Cacioppo, 1981). Since the idealized goal represents a perspective shared by the followers and promises to meet their hopes and aspirations, it tends to be within this latitude of acceptance in spite of its extreme discrepancy. Leaders then become charismatic as they succeed in changing their followers' attitudes to accept their advocated vision. We argue that leaders are charismatic when their vision represents an embodiment of a perspective shared by followers in an idealized form.

What are the attributes of charismatic leaders that make them successful advocates of their discrepant vision? Research on persuasive communication suggests that in order to be a successful advocate, one needs to be a credible communicator and that credibility comes from projecting an image of being a likable, trustworthy, and knowledgeable person (Hovland, Janis, and Kelley, 1953; Sears, Freedman, and Peplau, 1985).

It is the shared perspective of the vision and its potential for satisfying followers' needs that make leaders “likable” persons. Both the perceived similarity and the need satisfaction potential of the leaders form the basis of their attraction (Byrne, 1977; Rubin, 1973). However, the idealized (and therefore discrepant) vision also makes the leaders adorable persons deserving of respect and worthy of identification and imitation by the followers. It is this idealized aspect of the vision that makes them charismatic. Charismatic leaders are not just similar others who are generally liked (as popular consensus-seeking leaders) but similar others who are also distinct because of their idealized vision.

Articulating the Vision. In order to be charismatic, leaders not only need to have visions and plans for achieving them, but they must also be able to articulate their visions and strategies for action in effective ways so as to influence their followers. Here articulation involves two separate processes: articulation of the context and articulation of the leader's motivation to lead. First, charismatic leaders must effectively articulate for followers the following scenarios representing the context: the nature of the status quo and its shortcomings, their future vision, how, when realized, the future vision will remove existing deficiencies and provide fulfillment of the hopes of followers, and their plans of action for realizing their vision.

In articulating the context, the charismatic's verbal messages construct reality in such a way that only the positive features of the future vision and the negative features of the status quo are emphasized. The status quo is often presented as intolerable, and the vision is presented, in clear specific terms, as the most attractive and attainable alternative. In articulating these elements for subordinates, the leader often constructs several scenarios representing the status quo, the goal for the future, the needed changes, and the ease or difficulty of achieving the goal depending on available resources and constraints. In his or her scenarios, the charismatic leader attempts to create among followers a disenchantment or discontentment with the status quo, a strong identification with the future goal, and a compelling desire to be led in the direction of the goal in spite of environmental hurdles. This process of influencing the followers is very similar to the path-goal approach to leadership behavior advocated by many theorists (for example, see House, 1971).

Besides verbally describing the status quo, the future goal, and the means to achieve the future goal, charismatic leaders must also articulate their own motivation for leading their followers. Using expressive modes of action, both verbal and nonverbal, they manifest their convictions, self-confidence, and dedication to materialize what they advocate. In the use of rhetoric, words are selected to reflect their assertiveness, confidence, expertise, and concern for followers' needs. These same qualities may also be expressed through their dress, their appearance, and their body language. Charismatic leaders' use of rhetoric, high energy, persistence, unconventional and risky behavior, heroic deeds, and personal sacrifices all serve to articulate their high motivation and enthusiasm, which then become contagious among their followers. These behaviors form part of a charismatic leader's impression management.

Stage Three: Achieving the Vision

In the final stage of the leadership process, effective leaders build in followers a sense of trust in their abilities and clearly demonstrate the tactics and behaviors required to achieve the organization's goals. The charismatic leader does this by building trust through personal example and risk taking and through unconventional expertise. It is critical that followers develop a trust in the leader's vision. Generally, leaders are perceived as trustworthy when they advocate their position in a disinterested manner and demonstrate a concern for followers' needs rather than their own self-interest (Walster, Aronson, and Abrahams, 1966). However, in order to be charismatic, leaders must make these qualities appear extraordinary. They must transform their concern for followers' needs into a total dedication and commitment to the common cause they share with followers and express them in a disinterested and selfless manner. They must engage in exemplary acts that are perceived by followers as involving great personal risk, cost, and energy (Friedland, 1964). In this case, personal risk might include the possible loss of personal finances, the possibility of being fired or demoted, and the potential loss of formal or informal status, power, authority, and credibility. Examples of such behaviors entailing risk include Lee Iacocca's reduction of his salary to one dollar in his first year at Chrysler (Iacocca and Novak, 1984) and John DeLorean's confrontations with General Motors's senior management (Martin and Siehl, 1983). The higher the manifest personal cost or sacrifice for the common goal, the greater is the trustworthiness of a leader. The more leaders are able to demonstrate that they are indefatigable workers prepared to take on high personal risks or incur high personal costs in order to achieve their shared vision, the more they reflect charisma in the sense of being worthy of complete trust.

Finally, charismatic leaders must appear to be knowledgeable and experts in their areas of influence. Some degree of demonstrated expertise, such as reflected in successes in the past, may be a necessary condition for the attribution of charisma (Weber, [1924] 1947)—for example, Iacocca's responsibility for the Ford Mustang. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that the attribution of charisma is generally influenced by the expertise of leaders in two areas. First, charismatic leaders use their expertise in demonstrating the inadequacy of the traditional technology, rules, and regulations of the status quo as a means of achieving the shared vision (Weber, [1924] 1947). Second, charismatic leaders show an expertise in devising effective but unconventional strategies and plans of action (Conger, 1985). Leaders are perceived as charismatic when they demonstrate expertise in transcending the existing order through the use of unconventional or countercultural means. Iacocca's use of government-backed loans, money-back guarantees on cars, union representation on the board, and advertisements featuring himself are examples of unconventional strategic actions in the automobile industry.

The attribution of charisma to leaders also depends on followers' perceptions of their leaders' “revolutionary” and “countercultural” qualities (Berger, 1963; Conger, 1985; Dow, 1969; Friedland, 1964; Marcus, 1961). The countercultural qualities of leaders are partly manifested in their discrepant idealized visions. But more important, charismatic leaders must engage in unconventional, countercultural, and therefore innovative behavior while leading their followers toward the realization of their visions. Martin and Siehl (1983) demonstrated this in their analysis of John DeLorean's countercultural behavior at General Motors. Charismatic leaders are not consensual leaders but active innovators and entrepreneurs. Their plans and strategies for achieving desired changes and their exemplary acts of heroism involving personal risks or self-sacrificing behaviors have to be novel and unconventional. Their uncommon behavior, when successful, evokes in their followers emotional responses of surprise and admiration. Such uncommon behavior also leads to a dispositional attribution of charisma (or the possession of superhuman abilities).

Personal Power and Charisma

A leader's influence over followers can stem from different bases of power, as suggested by French and Raven (1959). Charismatic influence, however, stems from the leader's personal idiosyncratic power (referent and expert powers) rather than from their position power (legal, coercive, and reward powers), which is determined by organizational rules and regulations. Participative leaders also may use personal power as the basis of their influence. Their personal power, however, is derived from consensus seeking. In addition, some organizational leaders may use personal power through their benevolent but directive behavior. But charismatic leaders are different from both consensual and directive leaders in the use of their personal power. The sources of charismatic leaders' personal power are manifest in their elitist idealized vision, their entrepreneurial advocacy for radical changes, and their depth of knowledge and expertise. In charismatic leaders, all these personal qualities appear extraordinary to followers, and these extraordinary qualities form the basis of both their personal power and their charisma.

Charisma as a Constellation of Behaviors

Through the leadership or influence process model just discussed, we have identified a number of behavioral components that distinguish charismatic from noncharismatic leaders. These components are listed in Table 1. Although each component when manifested in a leader's behavior can contribute to a follower's attribution of charisma to the leader, we consider all of these components interrelated because they often appear in a given leader in the form of a constellation rather than in isolation. It is this constellation of behavior components that distinguishes charismatic leaders from other leaders.

Certain features of the components listed in Table 1 are critical for the perception of charisma in a leader. It is quite probable that effective and noncharismatic leaders will sometimes exhibit one or more of the behavioral components we have identified. However, the likelihood of followers attributing charisma to a leader will depend on three major features of these components: the number of these components manifested in a leader's behavior, the level of intensity of each component as expressed in a leader's behavior, and the level of saliency or importance of individual components as determined by the existing situation or organizational context.

As the number of behavioral components manifested in a leader's behavior increases, the likelihood of a follower's attribution of charisma to the leader also increases. Thus, a leader who is only skillful at detecting deficiencies in the status quo is less likely to be seen as charismatic than is one who not only detects deficiencies but also formulates future visions, articulates them, and devises unconventional means for achieving them.

Besides the total number of manifested behavioral components, leaders may differ in the magnitude (and/or frequency) of a given behavioral component they exhibit. The higher the manifest intensity or frequency of a behavior, the more likely it is to reflect charisma. Thus, leaders who engage in advocating highly discrepant and idealized visions and use highly unconventional means to achieve these visions are more likely to be perceived as charismatic. Likewise, leaders who express high personal commitment to an objective, who take high personal risk, and who use intense articulation techniques are more likely to be perceived as charismatic.

Finally, followers are more likely to attribute charisma to a leader when they perceive his or her behavior to be contextually appropriate and/or in congruence with their own values. Thus, in a traditional organizational culture that subscribes to conservative modes of behavior among employees and the use of conventional means to achieve organizational objectives, leaders who engage in excessive unconventional behavior may be viewed more as deviants than as charismatic figures. Similarly, a leader whose vision fails to incorporate important values and lacks relevance for the organizational context is unlikely to be perceived as charismatic. Certain behavioral components are more critical and effective sources of charisma in some organizational or cultural contexts, but not in others. For example, in some contexts, unconventionality may be less valued as an attribute of charisma than articulation skills, and in other contexts it may be more valued. The constellation of behaviors and their relative importance as determinants of charisma will differ from one organization to another or from one cultural (or national) context to another. Thus, in order to develop a charismatic influence, a leader must have an understanding of the appropriateness or importance of the various behavioral components for a given context.

Table 1. Distinguishing Attributes of Charismatic and Noncharismatic Leaders.

Implications for Research and Practice

In order to demystify the notion of charisma, we have presented a model that describes a set of behavioral components that form the basis of an attribution of charisma to leaders. On the basis of this model, we proposed in an earlier article a set of tentative hypotheses for future testing (Conger and Kanungo, 1987). This set of testable hypotheses is reproduced in Table 2. Evidence in the literature supports the general framework we have suggested here, but the specific predictions listed in Table 2 remain to be tested. The development and validation of several new scales may be necessary to capture the phenomenon of charismatic leadership within organizations. Such measurement devices would lead to testing the validity of this model.

Table 2. Some Testable Hypotheses on Charismatic Leadership.

In the framework we are proposing, understanding charismatic leadership involves two steps. We have viewed charisma as representing two sides of the same coin: a set of dispositional attributions by followers and a set of leaders' manifest behavior. The two sides are linked in the sense that the leader's behaviors form the basis of followers' attributions. A comprehensive understanding of the charismatic influence process will involve both the identification of the various components of leaders' behavior and assessment of how the components affect the perceptions and attributions of followers.

In order to validate the behavioral model we have proposed, two steps in the research process are necessary. First, our proposed behavioral and dispositional attributes of charismatic leaders require independent empirical confirmation. For convergent validity purposes, a behavioral attribute checklist or questionnaire could be developed that would employ the attributes we have described as well as those cited in the literature for other leadership forms. A group of test subjects would then be asked to identify leaders whom they perceive as charismatic and as noncharismatic. Respondents would be instructed to describe the distinguishing attributes of the charismatic and noncharismatic forms using the checklist. With this format, it would be possible to test whether an attribution of charisma is associated with the behavioral components we are describing. It would also be important to test these behavioral dimensions across various contexts and cultures to determine situational variations.

A recent study (Butala, 1987) designed to test the convergent validity of the charismatic leadership construct provides encouraging evidence in support of our model. In this study, a sample of 105 M.B.A. students were first asked to name two familiar effective leaders, one whom they considered charismatic and one noncharismatic. Following this, the students were then asked to describe these leaders using a checklist of 300 adjectives (Gough, 1952). Comparison of frequency counts of adjectives attributed to the charismatic and the noncharismatic leaders provided support for many of the distinguishing characteristics suggested in our model. For instance, charismatic leaders were perceived to be daring, reckless, energetic, enterprising, unconventional, rebellious, and emotional. In contrast, noncharismatics were seen to be conventional, conservative, reflective, serious, timid, organized, and aloof. Qualities such as patient, realistic, clear thinking, intelligent, and clever were seen in both types of leaders with equal frequency. These results require further confirmation.

The second step in the research process requires tests of discriminant validity of the charismatic leadership construct. This can be done by designing studies to demonstrate that some dependent variables (such as followers' trust) are related to charisma differently than other leadership constructs. These dependent variables are listed in Figure 1 under the organizational and individual outcomes of the leadership process. This type of research will establish the unique effects of charismatic leadership on organizational and individual (follower) outcomes.

The model also has direct implications for management. Specifically, if the behavioral components of charismatic leadership can be isolated, it may be possible to develop in managers several of the model's attributes. Films and cases employing critical incidents demonstrating the characteristics we are considering, as well as behavioral exercises, could be used to train managers. Also, assuming that charismatic leadership is important for organizational reform, companies may wish to select managers on the basis of the characteristics we have identified. The assumption is that individuals appropriate for reformer roles may be those with the dispositional characteristics described in this chapter (for example, managers who tend to have discrepant views). Certain tests, such as those already developed to test sensitivity to the environment (Kenny and Zacarro, 1983), could be administered to potential managerial candidates. The need for such training and selection procedures is likely to be particularly important in developing countries, where greater levels of organizational change are necessary to adopt new technologies and transform traditional ways of operating.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have outlined an influence process model of leadership. In each stage of the influence process we have identified a set of behavioral components that are critical for the attribution of charisma to a leader. In doing so, we have argued that charismatic leadership be viewed as another critical dimension of leadership behavior with important effects on organizational and followers' outcomes. Furthermore, we have presented a set of testable hypotheses derived from our model. It is our hope that future research will be directed toward testing and refining the model.

References

Bass, B. M. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press, 1985.

Berger, P. L. “Charisma and Religious Innovation: The Social Location of the Israelite Prophecy.” American Sociological Review, 1963, 28, 940–950.

Berlew, D. E. “Leadership and Organizational Excitement.” California Management Review, 1974, 17 (2), 21–30.

Blake, R. R., and Mouton, J. S. The Managerial Grid. Houston: Gulf, 1964.

Blau, P. “Critical Remarks on Weber's Theory of Authority.” American Political Science Review, 1963, 57 (2), 305–315.

Butala, B. “Charismatic Leadership: A Behavioral Study.” Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, 1987.

Byrne, D. The Attraction Paradigm. New York: Academic Press, 1977.

Conger, J. A. “Charismatic Leadership in Business: An Exploratory Study.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, School of Business Administration, Harvard University, 1985.

Conger, J. A., and Kanungo, R. N. “Towards a Behavioral Theory of Charismatic Leadership in Organizational Settings.” Academy of Management Review, 1987, 12, 637–647.

Dow, T. E., Jr. “The Theory of Charisma.” Sociological Quarterly, 1969, 10, 306–318.

Fiedler, F. F. A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967.

French, J. R., Jr., and Raven, B. H. “The Bases of Social Power.” In D. Cartwright (ed.), Studies of Social Power. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1959.

Friedland, W. H. “For a Sociological Concept of Charisma.” Social Forces, 1964, 43 (1), 18–26.

Gough, H. G. The Adjective Check List. Palo Alto, Calif.: Consulting Psychologist Press, 1952.

Hersey, P., and Blanchard, K. H. Management of Organizational Behavior. (4th ed.) Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1977.

House, R. J. “A Path-Goal Theory of Leadership Effectiveness.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 1971, 16, 321–332.

House, R.J. “A 1976 Theory of Charismatic Leadership.” In J. G. Hunt and L. L. Larson (eds.), Leadership: The Cutting Edge. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1977.

Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., and Kelley, H. H. Communication and Persuasion. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1953.

Hovland, C. I., and Pritzker, H. A. “Extent of Opinion Change as a Function of Amount of Change Advocated.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1957, 54, 257–261.

Iacocca, L., and Novak, W. Iacocca: An Autobiography. New York: Bantam Books, 1984.

Katz, D., and Kahn, R. L. The Social Psychology of Organizations. New York: Wiley, 1978.

Kenny, D. A., and Zacarro, S. J. “An Estimate of Variance Due to Traits in Leadership.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 1983, 68, 678–685.

Marcus, J. T. “Transcendence and Charisma.” The Western Political Quarterly, 1961, 14, 236–241.

Martin, J., and Siehl, C. “Organizational Culture and Counterculture: An Uneasy Symbiosis.” Organizational Dynamics, 1983, 12, 52–64.

Petty, R. E., and Cacioppo, J. T. Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches. Dubuque, Iowa: Brown, 1981.

Rubin, Z. Liking and Loving: An Invitation to Social Psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1973.

Sears, D. O., Freedman, L., and Peplau, L. A. Social Psychology. (5th ed.) Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1985.

Walster, E., Aronson, D., and Abrahams, D. “On Increasing the Persuasiveness of a Low-Prestige Communicator.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1966, 2, 325–342.

Weber, M. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. (A. M. Henderson and T. Parsons, trans.; T. Parsons, ed.) New York: Free Press, 1947. (Originally published 1924.)

Willner, A. R. The Spellbinders: Charismatic Political Leadership. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1984.

Yukl, G. A. Leadership in Organizations. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1981.

Zaleznik, A. “Managers and Leaders: Are They Different?” Harvard Business Review, 1977, 15 (3), 67–78.

Zaleznik, A., and Kets de Vries, M. Power and the Corporate Mind. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975.