10

Developing Transformational Leaders: A Life Span Approach

Bruce J. Avolio

Tracy C. Gibbons

“In archaic societies, the appropriate way to honor progenitors, mythical or actual, is to repeat their gestures and their sacred words. In ‘modern societies,’ the way to show esteem and honor is not to repeat but to build on; not ritually to invoke but productively to extend; not to follow in the footsteps but to widen the path” (Wapner and others, 1983; p. 111).

Much of the discussion in the previous chapters of this book has concentrated on the nature and the limits of charismatic leadership. In this chapter, our intent is to expand the discussion of charisma in the context of transformational leadership within a framework of developmental theory. Our primary objective is to explain how charismatic leaders develop them-selves and their followers.

In introducing the idea of development into an analysis of charismatic leadership, we make several assumptions. First, the development of charismatic leadership is assumed to be a transformational leadership process. Second, transformational leaders are assumed to be charismatic as well as intellectually stimulating, inspirational, and so forth; thus, to understand how charismatic leaders develop or transform others, we must broaden our scope of analysis to include all relevant facets of transformational leadership. Third, we assume that “pure” charismatics are not concerned with the development of others. Optimally, the pure charismatic has attracted followers' attention, convinced them of the merits of his or her vision, and established a strong following. Yet the pure charismatic does not focus on developing followers into leaders. At the extreme, charismatic leaders may fail to develop themselves, and in turn their missions may fail from a lack of sensitivity to environmental demands (Avolio and Bass, 1987). Our own conceptualization of the pure charismatic is similar to Howell's discussion of personalized charisma (Chapter Seven), while her socialized charisma is more in line with our conception of charismatic/transformational leadership. Finally, we view the charisma of the transformational leader as the emotional fuel that energizes and transforms followers into leaders.

We begin our discussion by examining the construct of leadership with respect to developmental theory. A discussion of transformational leadership follows, with an emphasis on explaining how development occurs. Findings from preliminary work on the developmental antecedents of charismatic/transformational leadership are also included, as well as recommendations for future research and training.

A One-Minute Critique

Leaders are by definition change (developmental) agents in organizations. Yet we know very little about how leaders develop followers (the process), how individual differences affect the time it takes a leader to develop one follower rather than another, and how specific life events moderate the influence a leader has on his or her followers. And while thousands of studies have examined the content, process, and impact of leadership, most of the literature has portrayed leadership as a “timeless” dimension rather than as an ongoing process (McCauley, 1986; Gordon and Rosen, 1981). Although there are exceptions, the majority of leadership studies have not examined leadership within life-span and developmental frameworks.

As such, research has yet to produce a strong developmental theory of leadership. By “strong” theory we mean one that attempts to explain changes in human behavior in terms of its form, the conditions contributing to behavioral change, and the time interval required for change to take place. Weak developmental theories note the occurrence of change but fail to explain the form and the conditions that contribute to or inhibit the change process.

Instead, the leadership literature is largely composed of research that has been collected cross-sectionally, whereby leadership and such outcome measures as effort, performance, and satisfaction are obtained at similar points in time. Yet using such cross-sectional research designs results in a single, static estimate of the leader's effect on followers' motivation and performance and inhibits researchers from effectively evaluating the developmental role that leaders take on in organizational settings.

Before we can begin evaluating developmental and transformational changes in followers that are attributed to charismatic leaders, we must first determine the appropriate time intervals within which to measure leadership and its effect(s) on followers. Deciding on appropriate intervals is essential to a model that describes how leaders influence higher- and lower-order needs in followers, as suggested by the transformational leadership model (Bass, 1985). Since development proceeds at different rates for different individuals, it is also essential to determine the time intervals in which to examine whether change correctly (or incorrectly) attributed to a leader has occurred. Building such parameters into our analysis of leadership is a prerequisite for testing the construct validity of a leadership model that depicts how charismatic leaders develop and transform situations and followers. A possible strategy is to operationalize expected changes due to leadership and then estimate the time interval necessary to assess the full impact of leadership on the relevant process and outcome variables.

An appropriate time interval will depend on the type of change that is expected, the individuals involved, and the organizational context in which change (higher- or lower-order) will occur. Estimating these intervals in which change is expected to occur will, however, require a closer look at both leader and follower interactions. A useful framework for analyzing leader-follower interactions is the vertical dyad linkage model (Graen and Cashman, 1975; Dansereau, Alutto, and Yammarino, 1985).

A Developmental Perspective

Before discussing our additions to Bass's (1985) model of transformational leadership, an appropriate framework for discussing developmental change and leadership is required. One of our primary assumptions is that developmental change should be viewed as a continuous process accumulated, for the most part, gradually and incrementally over time. As such, and contrary to popular crisis-stage models of development (Levinson, 1978), individual development results from smaller and less obvious incremental changes involving the circumstances of daily events and the individual's interpretation of those events. Development is not necessarily due to a crisis or abrupt change (Brim and Ryff, 1980; Campbell, 1980). Whereas crisis theories posit the resolution of a life crisis as the impetus for individual development, it is equally plausible that, for many, crisis is simply a reaction to the awareness of change or the need for change and not necessarily the driving force behind development.

Development, then, entails the accumulation of both minor and major events across one's life span resulting in what Whitbourne (1985) refers to as the life span construct. The life span construct is the script of an individual's past and present. It establishes a basic framework for interpreting future events and is the mechanism used to organize an individual's life experiences into an integrated and interpretable whole (Whitbourne, 1985). Explaining development, leadership or otherwise, using the life span construct also assumes that people play an active role in structuring their own development.

Development is also seen as a continuous process of change and reaction to life events that occur over time. For example, Campbell (1980) concludes that most adults do not partition their life spans into major age-related shifts or stages but rather see them as a continuous process of change and development without abrupt stages or crisis. The delineation of broad stages of development most likely underestimates the continuity, as well as the numerous transitions, associated with individual development (Gubrium and Burkholdt, 1977).

Some may argue, however, that there are common or universal developmental events or stages that are culturally determined and that occur at standard points in time for most, if not all, individuals. We, however, would argue that such constructs underestimate many areas of life span development. The three-stage model framework is too simplistic a classification system for capturing the dynamic nature of life span development and too simplistic to explain charismatic/transformational leadership.

The mode of analysis we recommend for studying charismatic/transformational leadership focuses on transitions (critical or not) using a longitudinal framework. The unit of analysis is the interaction of the leader with his or her environment over a specific time interval. A similar framework for studying human development was recommended by Murray (1938) and, more recently, by Stokals (1982). Both recommended an analysis of life span development that is unique to the individual but does not disregard historical events common to a particular individual or group.

Our framework is also tied to Werner's (1926, 1940) thesis on comparative developmental psychology—an organismic developmental systems approach. Werner discusses two key elements for studying change: the structural components (in our case, the leader, follower, and context) and the dynamic components (the interactions of the structural components). The components of systems, the relations among those components, and the interaction of the personal system with the environmental system are assumed to have a developmental order (Wapner and others, 1983; Werner, 1957). Over time, they become more differentiated. At the upper endpoint of the developmental continuum, optimal development was operationalized by Kaplan (1966) as “a differentiated and hierarchically integrated person-in-environment system with capacity for flexibility, freedom, self-mastery and ability to shift from one mode of person-in-environment relationship to another as required by goals, by the demands of the situation, and by the instrumentalities available” (p. 11). Kaplan's definition of optimal development comes close to describing several popular definitions of charismatic/transformational leaders (see Avolio and Bass, 1987).

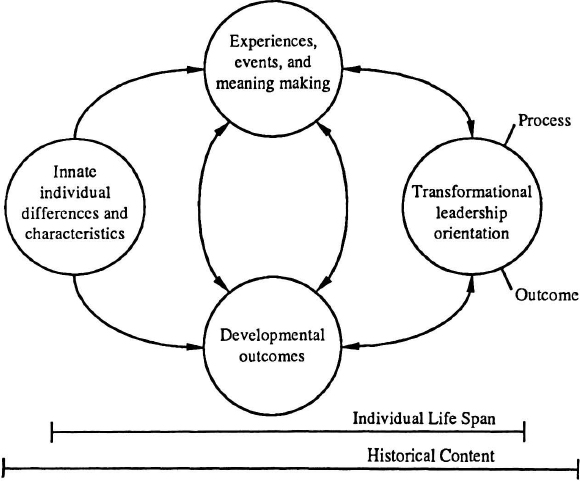

The developmental lens we have proposed for analyzing charismatic/transformational leadership has several important characteristics, which are summarized in Figure 1. First, critical and noncritical transitions of development are dependent on an individual reaction to major and minor life events, which in turn depend upon the life span construct developed by each individual. Second, developmental transitions associated with transformational leadership should be interpreted with respect to the time period in which they occur, such as individual or historical time. Third, the time interval selected in which to study developmental changes associated with charismatic/transformational leadership will vary depending on the phenomenon being studied—for example, the leader's own development, the followers' development, the development of the environmental/organizational context, and/or some interaction of the three.

Figure 1. How Transformational Leaders Develop and How They Develop Others.

To summarize, experiences and events are accumulated over personal and historical time and result in a meaning-making system that offers each individual a unique perspective of his or her stimulus world. The way in which life events are interpreted is a function of such individual characteristics as intelligence and cultural upbringing. The meaning-making lens used to interpret life events affects an individual's pattern of development. Development, in turn, affects the meaning-making system utilized by the individual to interpret his or her world. They feed into each other. Taken together, personal characteristics, developmental experiences and outcomes, and the individual's meaning-making system built up over time and used to interpret life events affect the leadership orientation exhibited by that individual at a particular time. The process shown in Figure 1 is continuous and interactive, and takes place across an individual's life span.

Overview of Transformational Leadership

Since Bass's (1981) discussion of transformational leadership in Stogdill's Handbook of Leadership, considerable data have accumulated regarding the factors that comprise transformational leadership, some of its effects on follower effort and performance, and certain developmental antecedents that instill leaders with transformational qualities. While these are discussed by Bass and by other chapter authors in this volume, it is important to note that charismatic leadership is central to the transformational process and accounts for the largest percentage of common variance in transformational leadership ratings. Followers want to emulate their charismatic leader, they place a great deal of trust in their leader's judgment, as well as in his or her mission, they support the leader's values and typically adopt them, and they frequently form strong emotional ties to the leader.

Charismatic/transformational leadership, however, differs from earlier conceptualizations of charisma (see, for example, House, 1977) in that the leader is also seen as demonstrating a concern for the individual needs of followers (treating followers on a one-to-one basis) and encouraging followers to look at old problems in new ways through intellectual stimulation. This is unlike purely charismatic leaders, who may intentionally or unintentionally fail to transform followers. Pure charismatics may find followers' desire for autonomy a threat to their own leadership and hence intentionally keep followers from developing. They may also unintentionally fail to recognize followers' needs (Avolio and Bass, 1987). And in regard to intellectual stimulation, we see a fundamental difference between the purely charismatic leader, who has trained followers to blind obedience or habituated subordination (Graham, 1987), and the transformational leader, who encourages followers to think on their own.

Understanding the antecedents to charismatic/transformational leadership theory comes at an appropriate time in the development of this construct. The concept of transformational leadership did not formally appear in the literature until Burns's 1978 book entitled Leadership was published. Since its introduction of this concept to the field of leadership, the focus in the literature has been primarily on operationalizing what transformational leadership is, who has it, what it can do, and how it differs from other conceptualizations of leadership. Although some disagreement still remains in the literature concerning these fundamental issues, it seems appropriate to turn our attention to analyzing transformational leadership using a life span orientation. The justification for a developmental analysis comes from the consensus in the field that transformational leaders change and develop followers. Equally important, transformational leaders also change and develop themselves.

Gibbons (1986) summarized and integrated three theories of human development to explain the origin, acquisition, and development of transformational leadership. Figure 2 provides an overview of those antecedent events and conditions that previously have been linked to the development of charismatic/transformational leadership. The three theories are the psychoanalytical, the humanistic, and the constructivist. All three theories lean toward explaining transformational leadership as having its primordial roots in childhood. For example, Bass (1960) identified several family factors, such as birth order, sibling relationships, the home environment, parental ambitions, and attitudes toward the child as having a significant influence on leadership development. He also credited peer group relationships and the nature of an individual's school environment with having an impact on leadership potential.

Figure 2. A Model of Life Span Events That Contribute to Leadership.

Psychoanalytical Theory. From a psychoanalytical perspective, Zaleznik (1977) attributed the development of charismatic leadership to early childhood experiences, although he assigned greater importance to crisis experiences, such as when an individual separates from his or her parents. His “twice-born” charismatic leaders experienced early development and separation from their parents as a crisis and a painful experience, which resulted in a sense of isolation, of being different (perhaps special), and in a turning away from the outer world. Corresponding with a shift inward, the twice borns became more dependent on their own beliefs and thoughts as their standard of reference for making decisions. They developed an inner strength and sense of resolution.

Through this resolution of inner conflict, disappointment, and problems, the leader moves to a level of development at which he or she can be responsible for resolving the conflicts, disappointments, and problems of others (Bass, 1985). According to the psychoanalytical model, higher-level stages of development are only possible through the resolution of early inner conflict (Zaleznik, 1963). Zaleznik (1984) portrayed development as a crusade for “self-mastery” through a field of internal conflicts. By learning how to deal with and resolve (master) personal conflict and disappointment in childhood, leaders can turn their attention to more substantive, far-reaching issues. Bass (1985) referred to the visionary qualities of charismatic/transformational leaders as a function of the leader's freedom from inner conflict. After getting their personal shops in order, charismatic/transformational leaders are free to look outward and beyond the time period in which they operate to solve significant problems (Zaleznik, 1984).

Humanistic Theory. The humanistic model of development stems from the work of Allport (1961), Rogers (1961), and Maslow (1970). Allport felt that all behaviors and thoughts were unique to the individual and could be understood by examining the individual's developmental history or what he called the life script. Maslow focused on the individual's innate potential. According to Maslow, environments shape an individual's development only to the degree that they help, permit, and encourage the potential that is already there to become actualized (Maslow, 1968). Similar to Maslow and Allport, Rogers viewed the optimum level of development as the “fully functioning” person. Rogers described such an individual as having characteristics similar to those in Maslow's stage of self-actualization: accepting of one's feelings, more creative than average, and more accepting of others. Rogers's point of departure with other humanistic theorists was in the variance in development he attributed to interactions with significant others, such as with one's parents. Human qualities, such as personal self-regard and inner self, were viewed by Rogers as dependent on the approval (or disapproval) received from one's parents in early childhood development (Rogers, 1951). Rogers's view of human development also differed from Maslow's and Allport's to the degree that he felt that interventions later in life, such as psychotherapy, could lead to overdue adjustments in development—that is, get the individual back on his or her optimal developmental track.

The views of humanists and psychoanalysts overlap with respect to the relevance of the inner self to an individual's personality and to transformational leadership development. While both humanistic and psychoanalytical theories can contribute to our understanding of charismatic/transformational leadership development, we consider them weak developmental theories in that each does not adequately explain changes in leadership development across the life span.

Constructivist Theory. The constructivist view of development, however, focuses on explaining how individuals perceive or make meaning of the world around them (Kegan, 1982; Kegan and Lahey, 1984). Kegan and Lahey's theory has more of a life span orientation than either the psychoanalytical or the humanistic model. Significant to our earlier discussion regarding the life span construct is the idea that people respond to change and life events according to their individual world view or meaning-making system (Kegan and Lahey, 1984).

Kegan and Lahey suggest that development is a function of the way people make meaning out of their experiences, regardless of their age. People at the same point in their life spans may experience events differently based on their interpretation of those events. The interpretation of an event is dependent upon an individual's life construct and his or her cognitive development level. Basing their discussion on Piagetian stages of cognitive development, Kegan and Lahey view leadership development as a function of “the qualitative change in the meaning system which occurs as one's cognitive complexity level increases” (Kegan and Lahey, 1984, p. 202). The meaning system employed by an individual to interpret events, in turn, is tied to his or her prior experiences and how those experiences were interpreted.

Kegan and Lahey refer to three cognitive stages or levels of adult development to explain three developmental phases of leadership—interpersonal, institutional, and interindividual. The three levels represent different stages of one's identity or ego development. At the primary level, the leader is able to switch back and forth between concern for others and concern for him- or herself. The individual's identity is codetermined based on other people's needs, the situation, and so forth. The interpersonal leader is seen shifting with the wind and is often labeled inconsistent. In stage two, the leader becomes more autonomous and self-directing; however, the identity he or she develops may be too rigidly adhered to with no built-in mechanism for alteration or self-correction. The leader's identity is inextricably linked to the organization's identity. Rather than being the shaper, such leaders are the shaped. In stage three, the individual's identity is more firmly established and independent. There is a capacity for self-reflection and correction not observed in stage two. In stage three (or interindividual), the leader is more concerned about development of systems and people than about their maintenance. The leader's identity transcends the present demands placed on him or her; thus, he or she is more willing and able to change and develop others as well as him- or herself.

Lewis and Kuhnert (1987) have generalized the constructivist view to describe the development of transformational leaders. Viewing development hierarchically and in stages, Lewis and Kuhnert discuss four qualitatively different stages or levels of leadership. At the lowest level (stage one), leaders are developmentally incapable of transcending their own self-interests and needs, while at the highest developmental level (stage four), transformational leaders operate out of a personal value system that transcends immediate transactions, goals, and individual loyalties. Leaders at stage four construct or make meaning out of the world through their end values. Stage four leaders have a self-determined sense of identity. As suggested by the psycho-analytical view, the leader is more inner-directed and therefore more able to transcend the interests of the moment. This inner-directedness provides a transformational view as an unusual energy for pursuing goals, missions, and, ultimately, the leader's vision. The leader's enthusiasm for an objective can become infectious. The sense of inner-direction, if translated properly by the leader, will attract followers who agree with the leader's end values. How effectively those end values are communicated and the degree to which followers identify with the leader's end values both result in what House (1977) described as charismatic leadership. The values of the leader and their expression become the foundation for higher-order change in followers (Bass, 1985; Waldman, Bass, and Einstein, 1987).

A Retrospective Study of the Developmental Life Events of Transformational Leaders

Gibbons's (1986) investigation represents the most comprehensive attempt to combine the three models of leadership development previously discussed in this chapter. Gibbons used the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) to differentiate transformational leaders from other types of leaders—transactional, laissez-faire, and management-by-exception—in a sample of top-level corporate executives. Her analysis of leadership development was based primarily on retrospective life histories generated from in-depth clinical interviews with sixteen individuals whose MLQ scores showed them to be transformational and transactional, pure transformational, pure transactional, or laissez-faire leaders. Gibbons's analysis of the qualitatively generated data resulted in the identification of seven key elements that encompass some of the significant antecedents to the development of transformational leadership. The seven factors, which, when present, appear to result in transformational leadership, are shown in Figure 3. (Note that the size of the circle presented in Figure 3 denotes the importance attributed to that factor in the development of transformational leadership.) These seven factors are:

Figure 3. A Model of Life Span Events That Contribute to Leadership.

- A predisposition is established as a result of parental encouragement and expectation to set high standards for achievement, which extends to many arenas of life. As children, these leaders are expected to be the best and are given a moderately high amount of early responsibility in the family.

- The family situation, conditions, and circumstances may be difficult and often demanding, but sufficient resources, both individual and systemic, are available to avoid being overwhelmed. Balance is the important condition and is relative to each family situation.

- The individual learns how to deal with his or her emotions, including conflict and disappointment and their effects, as well as other emotions and feelings. If this condition is not learned within the family, then it is learned by choice or necessity at a later point in the leader's life span.

- The leader has had many previous leadership opportunities and experiences in a variety of settings. (The transformational leaders studied often reflected on those experiences that helped shape them for the leadership position they occupied at the time of Gibbons's study.)

- The leaders have a strong desire to engage in developmental work, especially as adults. Such work is undertaken in a conscious, deliberate way, and it becomes so much a part of transformational leaders that it appears automatic. Development is an orientation or way of being, not a role transformational leaders take on. The same high standards and expectations that were learned as a child are applied to other areas of work and life. There is a willingness to take risks on behalf of one's personal development. Personal development is a primary work goal, as well as life goal.

- Workshops, events, other more formal, structured developmental activities, and relationships with influential people who may also have been role models are used to augment and enhance the developmental orientation and process. The activities selected are related to personal development and are not specifically confined to skill training in leadership. Short-term workshops are not viewed as being critically important to the development of transformational leadership.

- The leader views all experiences as learning experiences and demonstrates a strong tendency to be self-reflective and to integrate learning. The integrated learnings are more often than not used to make self-enhancing rather than self-limiting choices.

In sum, Gibbons's findings provided support for all three models of leadership development previously discussed. Moreover, her conclusions highlight the importance of using a developmental lens to study leadership, a lens that focuses on continuous and incremental life span changes. Finally, supporting earlier research by Campbell (1980) and Whitbourne (1985), Gibbons's results did not present consistent evidence that necessarily supports a “critical life events” model of leadership development.

Gibbons's findings affirm our earlier argument that there are commonalities across leaders with respect to developmental life experiences but there is no evidence for specific and/or universal stages of development that culminate in producing a charismatic/transformational leader. Rather, development of charismatic/transformational leaders is best characterized as a life span process of change with early, as well as later, life events affecting the development of leadership potential.

It suffices to say that companies and/or individuals who rely principally on one or even a few developmental strategies for building transformational leaders will probably be disappointed, since the most successful developmental programs are those that reflect the individual and his or her unique needs and strengths. The critical elements making up the chemistry of a charismatic/transformational leader appear to vary across individual leaders.

Gibbons's work does represent one of the most comprehensive studies to date of the antecedents to charismatic/transformational leadership. However, her conclusions are based on a retrospective analysis and reconstruction of the leader's life history and events and therefore are subject to errors of omission and intrusion. People remember events on the basis of their reconstruction of those events in recall, not necessarily the actual events or facts (Cantor and Mischel, 1977; Phillips and Lord, 1982). For example, one may initially classify an experience as unpleasant but later in his or her life span go back and reclassify the experience as developmental—seeing the experience as having made a positive contribution to development. The key question is how much of anyone's inner self is a composite of reconstructed prior events and experiences? Also, to what extent are the developmental stages referred to in the literature actually an explanation of developmental processes rather than merely a convenient system of classification for recalling events? Nevertheless, while criticizing retrospective accounts as a means of conducting life span leadership research, one must realize that at present there are no ongoing longitudinal research studies of charismatic/transformational leadership. The type of data needed to build a strong developmental theory of leadership is still many years away from being collected.

Although there are no longitudinal research programs currently studying charismatic/transformational leadership, the Management Potential Study conducted at AT&T has produced some interesting parallels to Gibbons's findings (see Bray, Campbell, and Grant, 1974; Bray and Howard, 1983). Specifically, the overlap between the characteristics associated with transformational leaders and what Bray, Campbell, and Grant (1974) called the “enlargers” in their study of managers at AT&T is rather direct. Enlargers are attracted to challenges and to extending themselves, demonstrate greater than average emotional and intellectual independence (inner self), desire more responsibility and autonomy than others, and have developed a more sophisticated framework for making meaning out of reality (Lewis and Kuhnert's [1987] stage four leaders). Also, supporting Gibbons's conclusions, intrapersonal development over the two decades of data collection in the Management Potential Study was seen as a key factor in the success (rate of promotion) of the enlargers at AT&T (Bray and Howard, 1983).

In sum, our analysis of the models presented in this section argues in favor of looking at leadership as a continuous developmental process. Up to this point, based on the focus of previous literature, the emphasis in our discussion has been on the leaders' development and in particular on their personality/cognitive development. Each of the models reviewed has made a contribution to our understanding of how charismatic/transformational leaders develop. Our primary criticism of all three models, however, is that they all fall into the category of weak developmental theories. The strongest of the developmental theories—the constructivist view—still falls short of explaining how developmental change and transitions occur. Moreover, the central focus of the constructivist's explanation of change is based on developmental stages. Unfortunately, the stage theories cited do not explain how transitions between and within stages occur or whether passing through each of the stages in a prescribed order is necessary to achieve the highest level of development. However, the classification system proposed by Lewis and Kuhnert (1987) is useful in helping us capture leadership development as an orderable process of increasing complexity and differentiation (the orthogenetic principle). Its fundamental flaw is the idea that leaders need to be at the highest stage of cognitive development in order to be charismatic and transformational. Our view is that charismatic/transformational leadership occurs relative to the group with which the leader interacts and that transformational leadership can occur even at lower levels of cognitive development.

Emotional and Cognitive Development of Transformational Leaders and Their Followers

Most of the prior research on charismatic/transformational leadership has been conducted with top organizational leaders, with the exception of the work of Bass and his colleagues. Therefore, we have a theory of charismatic/transformational leadership that is bounded by the sample characteristics of the population upon which it has been construct validated.

There are two important distinctions to be made here. First, in terms of the individual, transformational leadership can occur at different levels of cognitive and emotional development. There is no empirical evidence that a certain stage of development or specific cutoff must be reached before one can be a charismatic/transformational leader. The level of individual development required to be transformational is, in part, relative to the developmental level of the individual or group being led. Raising the needs of followers who are at the lowest developmental level to a qualitatively higher level is transformational. However, previous authors have often referred to charismatic/transformational leadership as a dichotomous condition—that is, one either is or is not transformational—when in fact it is a matter of degree.

The second distinction involves the level within an organization at which charismatic/transformational leadership is observed. Recent evidence summarized by Avolio and Bass (1987) shows that charismatic/transformational leadership can occur at all organizational levels in varying degrees. The charismatic/transformational leadership qualities we commonly associate with top corporate leaders appear to also be present in leaders at lower levels of the organizational hierarchy. In this case, the degree of charismatic/transformational leadership observed is relative to the organizational level. At different levels, as well as in different organizational settings, the likelihood of observing some charismatic/transformational leadership varies.

One assumption about a charismatic/transformational leader's developmental level is clear: A leader who operates at a lower developmental level than his or her followers cannot transform followers to a level higher than his or her own. Conversely, a leader who views the world from a developmental level that is not understood by his or her followers will also have difficulty transforming followers to his or her way of thinking. Tichy and Devanna (1986), in their summarization of transformational leaders, suggest that the more successful transformational leaders are able to “dumb down” their vision to grab followers' interest, attention, and understanding. We hope that our discussion here puts a new light on the relativity of “dumbing down” the leader's message.

After interviewing ninety leaders, Bennis and Nanus (1985) reported that what differentiates leaders from nonleaders is a commitment to personal development as well as to the development of others. Similarly, Burns (1978), in his analysis of world-class political leaders, concluded that transformational leaders are characterized by a desire and intrinsic drive to engage in growth and development of the self. Bass (1985) similarly described transformational leaders as continually developing to higher levels and to developing followers into leaders. Gibbons (1986) concluded that transformational leaders are eager to develop and challenge themselves consciously throughout their careers. Similarly, providing challenges is also a key factor in the development and transformation of their followers.

Berlew and Hall (1966) reported that the more challenging one's first job with a company, the greater one's advancement rate will be within the company-Early job challenge also has been correlated with developmental career success in several other research investigations (Bray, Campbell, and Grant, 1974; Broderick, 1983; Davies and Easterby-Smith, 1984; Digman, 1978; Vicino and Bass, 1978). If we assume that these results are not totally attributable to methodological artifacts, such as more able people being selected for more challenging jobs or more challenging jobs increasing the visibility of an individual in his or her organization (Kanter, 1977), then there are two developmental connections that can be drawn to charismatic/transformational leadership. First, providing intellectual challenges for followers can affect the followers' cognitive development by encouraging the development of new information structures or cognitive scripts to address the impending challenge. The developmental process is analogous to our earlier discussion of how life events shape an individual's life construct. Second, job challenges can—and usually do—result in increased levels of emotional stress. The increased stress results in a need to seek ways to cope effectively with the challenge. If the challenge is appropriate for the individual's current developmental level (or potential), then challenge can result in emotional development as well. This situation is similar to our earlier discussion of overcoming early life conflicts/transitions and the impact of those events on the development of the inner self. If we expand on Zaleznik's (1977) concept of the twice-born leader, challenges throughout life, job or otherwise, can potentially stimulate a partial (or total) reevaluation of the inner self each time a minor (or major) challenge is confronted.

Providing intellectual challenges to followers promotes a key facet of individual development—the evolution of meaning-making systems to higher levels of cognitive complexity (Kohlberg, 1969; Loevinger, 1966; Merron, Fisher, and Torbert, 1986). Developing an ability in followers to see problems through a more sophisticated and creative lens reduces the use of more dogmatic approaches to problem solving on the job (Costa and McCrae, 1980). Merron, Fisher, and Torbert (1986) found that managers at higher developmental levels see problems as opportunities to observe and learn; managers at lower developmental levels see problems as fires to be put out.

Intellectual stimulation is also an important component of building autonomy in followers or developing followers into leaders. Intellectual stimulation may encourage the acceptance of others who have different points of view (Bartunek, Gordon, and Weatherby, 1983), which ties into an important facet of emotional development—one's level of empathy for other people's needs. Transformational leaders show empathy toward followers through individualized consideration (Bass, 1985). Development leads to higher forms of empathy, such as those described by Kohlberg in his moral development stage (Kohlberg, 1969). Part of developing followers' individualized consideration (empathy) is to move them developmentally from being able to recognize affective states in others to being able to assume the perspectives of others and ultimately to be responsive to them. How much empathy followers are capable of depends on their view of the world (or meaning-making system) and their level of emotional development (Feshbach, 1978, 1982; Parke and Asher, 1983). Leaders must concentrate on the cognitive and emotional development of followers if the followers are to lead themselves as well as others and ultimately transform.

The presentation of challenges to followers provides opportunities—for those who are developmentally ready to accept them—to learn and develop from the challenges. Lessons learned from a challenge, whether it was handled successfully or not, can be used as a basis for creating future opportunities in an individual's life span. All problems can be viewed as learning experiences, both cognitively and emotionally; to do so is to be seen as a transformational leader (Gibbons, 1986).

Of course, challenges can also lead to regression or the institutionalization of nondevelopment. Salaman (1978) described how nondevelopment became institutionalized in an organizational case study of an autocratic leader. The autocratic leader described by Salaman institutionalized his power base, as well as nondevelopment, by overseeing all decisions, personally selecting all of his subordinates, ambiguously describing all jobs, and keeping to himself information necessary for making even the lowest-level decision. Eventually, no one in the organization would undertake new initiatives without explicit permission from the leader. Self-doubt and the doubting of co-workers' competence cascaded throughout the organization. Everyone became convinced that everyone else was incompetent, which led to over-regulation and increasing levels of institutional controls. When the leader was finally removed, the controls became worse: Non-development had become institutionalized.

Challenge, as we have already seen from Gibbons's (1986) results, can be developmental and transformational. Unlike the challenges confronting the transformational leaders in Gibbons's sample, the people in the autocratically run organization described by Salaman (1978) felt no sense of balance between the challenge and the support and other resources made available to them. Obviously, both support and resources were intentionally withheld by the autocratic leader, which led to increased dependence on the person in charge and less desire for growth and individual development. Charismatic/transformational leadership thrives in an environment in which some sort of balance is maintained. Transformation and development also can become institutionalized and have been shown to cascade from one level of an organization to the next (Bass, Waldman, Avolio, and Bebb, 1987).

In sum, charismatic/transformational leaders provide challenges to both followers and themselves to move to higher levels of development. By addressing those challenges and building some record of successful achievement, the leader develops to a higher level of emotional and cognitive development. A leader's level of success in overcoming challenges has a direct bearing on his or her level of perceived self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977). Self-efficacy, or the confidence an individual has in his or her ability to overcome a challenge, is an integral component of the development of transformational leadership.

Self-Efficacy, Self-Management, and Self-Development

A useful model for evaluating individual development, particularly development linked to personal challenges, is provided by Bandura's (1977) discussion of social learning theory. According to social learning theorists, behavior is a function of both internal and external events. Self-efficacy represents one's belief that a certain amount of effort will result in the achievement of a desired outcome. The internal mechanism to which Bandura refers is represented by feelings of self-efficacy, while the external event is the challenge and the risk that goes along with that challenge. A significant part of developing or transforming followers is developing their feelings of self-efficacy. The four primary contributors to self-efficacy through which transformational leaders can affect followers' development are acknowledging previous accomplishments, providing emotional challenges, conveying high expectations, and modeling appropriate strategies for success. Charismatic/transformational leaders can develop a follower's self-efficacy in the following manner:

- The leader provides for followers tasks that result in experiences of success. Incremental successes encourage followers to pursue more difficult objectives. As feelings of self-efficacy develop, the probability assigned by followers to the risk of failure decreases. Explicit challenges also provide for the development of an alteration in an individual's meaning-making system.

- The leader gets the followers appropriately involved by providing emotional challenges, which results in higher intrinsic motivation and an increase in feelings of self-efficacy.

- The leader's ability to convey the importance of completing a task (verbal persuasion) for the leader's and follower's goals, values, mission, or even their vision increases the probability that the follower will attempt to accomplish the task.

- The leader models for the follower appropriate strategies for achieving success.

By raising followers' self-efficacy levels, the charismatic/transformational leader enables those followers to address more challenging problems. A further logical extension of developing self-efficacy in followers is the institutionalization of self-control and self-development.

Manz and Sims (1980) have used social learning theory as a framework for discussing the development of self-management skills. They recommend that, in order to develop self-management skills (or to transform followers into leaders), we need to concentrate on both environmental planning and behavioral change. Based on social learning theory, the simplest suggestion for developing followers into leaders and/or raising personal standards is to have leaders model self-management techniques (Bandura and Cervone, 1986). However, Manz and Sims (1986) recently found that simple modeling does not result in the desired behavioral effects. Their research showed that followers who observed specific behaviors modeled by a leader (simple modeling) did not adopt those behaviors beyond chance levels. These results demonstrate that there are more complex linkages between behavioral modeling and the behaviors we are attempting to develop than a simple imitation-demand effect model would indicate. In order to change and develop followers into leaders, we will have to do more than simply model desirable behaviors.

Another primary goal of transformational leadership is to develop in followers mechanisms for self-confidence and self-development. The leader transforms followers into leaders who are responsible for their own actions, behaviors, performance, and development. For some followers, this is represented by a gradual developmental process in which the leader reduces external reinforcement for specific behaviors as internal self-control mechanisms come into place; for others, the process may be accelerated if they are developmentally able and willing to take on more responsibility. Social learning theory is useful for understanding how transformational leaders both shape behaviors to desired end states and affect the cognitive scripts or mental road maps followers use to interpret the world around them.

In addition to social learning theory, we have put forth a life span orientation to help examine the events that move people to developmental levels at which they are able to handle more responsibility for their own behavior and eventually, for some, the behavior of others. The development of our understanding of how self-management comes about and the effects that charismatic/transformational leadership can have on the process of shifting from external to internal controls should provide a more comprehensive view of individual development of leaders in organizational settings. The biggest contributor to understanding how development takes place is understanding how the personal history of an individual has contributed to his or her current developmental level (Bandura and Cervone, 1986).

Conclusion

Our discussion has focused primarily on the dynamic components and processes underlying a form of leadership concerned with the development of followers. The model of transformational leadership presented by Bass (1985) has been used as a basis for discussing leadership development as a transformative process—a process that entails a progressive reorganization and reformulation of frames of reference and that results in higher levels of development. Heeding the advice of Weick (1979), we have attempted to blend together different theoretical views and perspectives (Weick's theory of complementarity) into a broader understanding of a complex phenomenon called charismatic/transformational leadership.

Some of the groundwork has been established to move the field a step closer to a strong developmental theory of leadership. A significant amount of work still needs to be accomplished before that goal is realized. In the interest of molding the frame of reference for studying charismatic/transformational leadership further, we have outlined some additional ideas for future research to consider. First, Bandura and Cervone (1986) have indicated that the single most important contributor to self-efficacy is the individual's personal history. Since self-efficacy plays such an integral role in the development of followers, greater attention needs to be paid to the connection between life events, self-efficacy, and developmental leadership. Individually perceived self-efficacy does directly relate to perseverance, level of effort, and eventual task accomplishment. Charismatic/transformational leaders can affect self-efficacy through their charisma or by providing a common vision for followers to make them feel stronger and more in control of their own destinies; through intellectual stimulation by providing a different frame of reference to overcome any impediments; and through individualized consideration or elevation of follower needs to accomplish more and to take more personal responsibility for their self-development. Second, we need to explore in greater detail the developmental antecedents to charismatic/transformational leadership. This will involve a reorientation of our approach to studying leadership—moving away from a timeless orientation to one that recognizes the importance of life events in the shaping of individual life constructs. It will also require the following assumption: The developmental experiences of individuals that result in charismatic/transformational leaders are orderable but not necessarily universal. And third, it will be worthwhile for leadership researchers to develop some guidelines for determining the length of time necessary for a leader to have some influence on followers in terms of development, effort levels, and also performance.

One specific reason for incorporating time intervals into our study of leadership relates to what Bass (1985) referred to as higher- and lower-order change in followers. With lower-order change, a charismatic/transformational leader is attempting to identify a follower's current material and psychic needs and to help provide a job environment that can satisfy those needs. The time interval necessary for achieving lower-order change should be shorter than the interval necessary for a leader to influence higher-order change—change in which a follower's needs, goals, desires, and values are qualitatively elevated and altered. Looking at higher- and lower-order change along a continuum regarding the degree of change expected should help determine when and where measurement of the effects of charismatic/transformational leadership should take place.

A second advantage of studying leadership with respect to time concerns the information it will provide about leadership itself. Assuming as we have that leadership is a continuous, progressive, developmental process, knowing how certain leaders' actions effect more or less immediate change in followers should offer some insights into the leadership process itself. Specifically, we can learn which leadership actions are more (or less) effective, which leadership actions take more time to incubate before change can be observed, and what type of follower responds more or less readily to those actions. By examining leadership according to time and inter- and intraindividual change, we can begin to build a model of leadership that more accurately predicts a leader's ability to influence individual as well as group behavior within appropriately defined time intervals.

Evaluating effects of charismatic/transformational leadership will require some additional changes in research strategy. A combination of longitudinal and cross-sectional research designs seems appropriate. A cross-sequential design may be the most appropriate model for maximizing the amount of information one can obtain in the shortest possible time. With a cross-sequential design, we start by collecting data cross-sectionally at the first period of measurement, then we follow respective cohorts over time longitudinally. Using this design, we can examine both inter- and intraindividual change while also looking at the effects of time, of measurement, and of cohort membership on the dependent variables of interest.

Short-term experimental simulations are appropriate when used to establish preliminary groundwork on the rate and direction of change expected due to certain leadership actions and behaviors. However, analyzing higher-order changes in followers will require a longer-term strategy to capture the phenomenon under investigation.

Given what we already know about charismatic/transformational leaders, we can offer the following recommendations for developing such leaders in organizations:

- The MLQ survey developed by Bass and his colleagues can be used initially to help identify charismatic/transformational leaders and also to make individuals aware of where they stand with respect to being charismatic/transformational leaders.

- Building on self-awareness, a developmental plan can be constructed that incorporates the strengths and weaknesses of the leader. The plan should have a life span orientation with respect to how the individual leader will build on his or her strengths while reducing his or her weaknesses. The plan must be individually oriented, keyed to earlier life events that can be obtained through interviews or biographical surveys, and flexible enough to accommodate changes in the individual and in the context in which he or she operates.

- Behavior and skills exhibited by charismatic/transformational leaders can be taught in workshops focused on intrapersonal (self-) development. Much of what we already know concerning self-development and confidence building can be used in the development of the charismatic/transformational leader.

- Emphasis needs to be placed on transferring skills and behaviors learned in workbooks back to the job. A careful analysis of potential “roadblocks” in the development of a charismatic/transformational leader should be identified. Optimally, training can take place on the job, making appropriate changes in context and culture to accommodate the developmental aspirations of the leader.

- All of our previous recommendations lead to one basic conclusion: The program of intervention should focus on changing the meaning-making system of the individual to approximate the framework that would be used by a charismatic/transformational leader.

This chapter has discussed charismatic/transformational leadership as a developmental process that unfolds across the life span. Empirical work is now needed to evaluate in a more systematic manner the developmental factors that result in what Bass and his colleagues refer to as the optimal form of leadership. We hope that our discussion has established a new frame of reference for studying leadership as it must be studied—using a developmental perspective.

References

Allport, G. W. Pattern and Growth in Personality. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1961.

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. Organizational Learning. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1978.

Avolio, B. J., and Bass, B. M. “Charisma and Beyond.” In J. G. Hunt (ed.), Emerging Leadership Vistas. Elmsford, N.Y.: Pergamon Press, 1987.

Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1977.

Bandura, A., and Cervone, D. “Differential Engagement of Self-Reactive Influences in Cognitive Motivation.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 1986, 38, 92–113.

Bartunek, J. M., Gordon, J. R., and Weatherby, R. P. “Developing Complicated Understanding in Administrators.” Academy of Management Review, 1983, 8, 273–284.

Bass, B. M. Leadership, Psychology and Organizational Behavior. New York: Harper & Row, 1960.

Bass, B. M. Stogdill's Handbook of Leadership. New York: Free Press, 1981.

Bass, B. M. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press, 1985.

Bass, B. M., Waldman, D. A., Avolio, B. J., and Bebb, M. “Transformational Leadership and the Falling Dominoes Effect.” Group and Organizational Studies, 1987, 12, 73–87.

Bennis, W., and Nanus, B. Leaders: The Strategies for Taking Charge. New York: Harper & Row, 1985.

Berlew, D. E., and Hall, D. T. “The Socialization of Managers: Effects of Expectations on Performance.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 1966, 11, 207–233.

Bray, D. W., Campbell, R. J., and Grant, D. L. Formative Years in Business. New York: Wiley, 1974.

Bray, D. W., and Howard, A. “The AT&T Longitudinal Studies of Managers.” In K. W. Schaie (ed.), Longitudinal Studies of Adult Psychological Development. New York: Guilford Press, 1983.

Brim, O. G., and Ryff, C. D. “On the Properties of Life Events.” Lifespan Development and Behavior, 1980, 3, 367–388.

Broderick, R. “How Honeywell Teaches Its Managers to Manage.” Training, Jan. 1983, pp. 18–22.

Burns, J. M. Leadership. New York: Harper & Row, 1978.

Campbell, A. The Sense of Well-Being in America. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1980.

Cantor, N., and Mischel, W. “Traits as Prototypes: Effects on Recognition Memory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1977, 35, 38–48.

Costa, P. T., Jr., and McCrae, R. R. “Still Stable After All These Years: Personality as a Key to Some Issues in Aging.” In P. B. Baltes and O. G. Brim (eds.), Lifespan Development and Behavior. Vol. 3. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1980.

Dansereau, F., Alutto, J. A., and Yammarino, F.J. Theory Testing in Organizational Behavior: The Varient Approach. Engle-wood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1985.

Davies, J., and Easterby-Smith, N. “Learning and Developing from Managerial Work Experiences.” Journal of Management Studies, 1984, 2, 1969–1983.

Digman, L. A. “How Well-Managed Organizations Develop Their Executives.” Organizational Dynamics, 1978, 1, 63–79.

Feshbach, N. D. “Studies of Empathic Behavior in Children.” In B. A. Maher (ed.), Progress in Experimental Personality Research. Vol. 8. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1978.

Feshbach, N. D. “Sex Differences in Empathy and Social Behavior in Children.” In N. Eisenberg-Berg (ed.), The Development of Prosocial Behavior. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1982.

Gibbons, T. C. “Revisiting the Question of Born vs. Made: Toward a Theory of Development of Transformational Leaders.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Human and Organization Systems, Fielding Institute, 1986.

Gordon, G. E., and Rosen, N. “Critical Factors in Leadership Succession.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 1981, 27, 227–254.

Graen, G., and Cashman, J. F. “A Role-Making Model of Leadership in Formal Organizations: A Developmental Approach.” In J. G. Hunt and L. L. Larson (eds.), Leadership Frontiers. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1975.

Graham, J. W. “The Essence of Leadership: Fostering Follower Autonomy, Not Automatic Followership.” In J. G. Hunt (ed.), Emerging Leadership Vistas. Elmsford, N.Y.: Pergamon Press, 1987.

Gubrium, J. F., and Burkholdt, D. R. Toward Maturity: The Social Processing of Human Development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1977.

House, R.J. “A 1976 Theory of Charismatic Leadership.” In J. G. Hunt and L. L. Larson (eds.), Leadership: The Cutting Edge. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1977.

Kanter, R. M. Men and Women of the Corporation. New York: Basic Books, 1977.

Kaplan, B. “The Comparative Developmental Approach and Its Application to Symbolization and Language in Psycho-pathology.” In S. Arieti (ed.), American Handbook of Psychiatry. Vol. 3. New York: Basic Books, 1966.

Kegan, R. The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982.

Kegan, R., and Lahey, L. L. “Adult Leadership and Adult Development: A Constructivist View.” In B. Kellerman (ed.), Leadership: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1984.

Kohlberg, L. “Stage and Sequence: The Cognitive-Developmental Approach to Socialization.” In D. A. Goslin (ed.), Handbook of Socialization Theory and Research. Skokie, I11.: Rand McNally, 1969.

Levinson, D. The Seasons of a Man's Life. New York: Ballantine Books, 1978.

Lewis, P., and Kuhnert, K. “Post-Transactional Leaders: A Constructive Developmental View.” Paper presented at the second annual conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Atlanta, Aug. 1987.

Loevinger, J. “The Meaning and Measurement of Ego Development.” American Psychologist, 1966, 21, 195–206.

McCauley, C. D. Developmental Experiences in Managerial Work: A Literature Review. Technical Report No. 26. Greensboro, N.C.: Center for Creative Leadership, 1986.

Manz, C. C., and Sims, H. P., Jr. “Self-Management as a Substitute for Leadership: A Social Learning Theory Perspective.” Academy of Management Review, 1980, 5, 361–367.

Manz, C. C., and Sims, H. P. “Beyond Imitation: Complex Behavior and Affective Linkages Resulting from Exposure to Leadership Training Models.'' Journal of Applied Psychology, 1986, 71, 571–578.

Margerison, C., and Kakabadse, A. How American Executives Succeed. New York: American Management Association, 1984.

Maslow, A. H. Toward a Psychology of Being. (2nd ed.) New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1968.

Maslow, A. H. Motivation and Personality. (2nd ed.) New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

Merron, D., Fisher, D., and Torbert, W. R. “Meaning Making and Managerial Effectiveness: A Developmental Perspective.” Paper presented at the national meeting of the Academy of Management, Chicago, Aug. 1986.

Murray, H. A. Explorations in Personality. New York: Oxford University Press, 1938.

Parke, R. D., and Asher, S. R. “Social and Personality Development.” Annual Review of Psychology, 1983, 34, 465–509.

Phillips, J. S., and Lord, R. G. “Schematic Information Processing and Perceptions of Leadership in Problem-Solving Groups Journal of Applied Psychology, 1982, 67, 486–492.

Rogers, C. R. Client-Centered Therapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951.

Rogers, C. R. On Becoming a Person: A Therapist's View of Psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961.

Salaman, G. “An Historical Discontinuity: From Charisma to Routinization.” Human Relations, 1978, 30, 373–388.

Stokals, D. “Environmental Psychology: A Coming of Age.” In A. Kraut (ed.), G. Stanley Hall Lecture Series. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 1982.

Tichy, N. M., and Devanna, M. A. The Transformational Leader. New York: Wiley, 1986.

Vicino, F. L., and Bass, B. M. “Lifespace Variables and Managerial Success.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 1978, 63, 81–88.

Waldman, D. A., Bass, B. M., and Einstein, W. O. “Effort, Performance and Transformational Leadership in Industrial and Military Service.” Journal of Occupational Psychology, 1987, 60, 1–10.

Wapner, S., and others. “An Examination of Studies of Critical Transitions Through the Life Cycle.” In S. Wapner and B. Kaplan (eds.), Toward a Holistic Developmental Psychology. Hillside, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1983.

Weick, K. The Social Psychology of Organizations. (2nd ed.) Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979.

Werner, H. Einfuhrungindie Entwicklungs-Psychologie. Leipzig, E. Germany: Barth, 1926.

Werner, H. Comparative Psychology of Mental Development. New York: Harper & Row, 1940.

Werner, H. “The Concept of Development from a Comparative and Organismic Point of View.” In D. B. Harris (ed.), The Concept of Development. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1957.

Whitbourne, S. K. “The Psychological Connection of the Lifespan.” In J. E. Birren and K. W. Schaie (eds.), The Psychology and Aging Handbook. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1985.

Zaleznik, A. “The Human Dilemmas of Leadership.” Harvard Business Review, 1963, 41, 49–55.

Zaleznik, A. “Managers and Leaders: Are They Different?” Harvard Business Review, 1977, 15, 67–78.

Zaleznik, A. “Charismatic and Consensus Leaders: A Psychological Comparison.” In M.F.R. Kets de Vries (ed.), The Irrational Executive: Psychoanalytic Explorations in Management. New York: International Universities Press, 1984.