7

Two Faces of Charisma: Socialized and Personalized Leadership in Organizations

Jane M. Howell

As several chapter authors have discussed, charismatic and transformational leadership have recently emerged as important concepts among organizational leadership scholars. Political scientist James MacGregor Burns (1978) initiated the distinction between exchange-oriented transactional leaders, who reward followers for reaching established objectives, and transformational leaders, who inspire followers to transcend their immediate self-interests for superordinate goals. In their best-selling book, In Search of Excellence, Peters and Waterman (1982) observe that at some point in the histories of successfully managed companies transformational leaders have arisen and instilled purpose, shaped values, and engendered excitement. In his recent book, Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations, Bass (1985) argues that transformational leadership is necessary to promote follower performance beyond ordinary limits. Finally, House and Singh (1987), in reviewing the burgeoning research on the behavior and effects of charismatic and transformational leaders, conclude that such leaders profoundly influence follower effort, performance, and affective responses toward them.

Despite the increased attention being focused on transformational and charismatic leadership in both the academic literature and the popular press, to date no scholarly consensus has emerged on the precise application of the concept of charisma. The term charismatic has been applied to very diverse leaders emerging in political arenas (Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Fidel Castro, Franklin Delano Roosevelt), in religious spheres (Jesus Christ, Jim Jones), in social movement organizations (Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X), and in business organizations (Lee Iacocca, Mary Kay Ash, John DeLorean). However, such a widespread application of the term obscures the term's meaning.

If the concept of charisma is to serve a useful purpose in scientific inquiry, then it cannot embrace leadership styles as disparate as those cited above. By distilling the elements that differentiate the range of leaders captured within this broad concept, the explanatory power of charisma will be increased. Therefore, a theory that distinguishes among different forms of charisma is proposed in this chapter. The theory looks not only at the possibilities of charismatic leadership, but, importantly, also at its limitations. For while the reader of this volume may be developing a sense of charisma's profound impact, it must be seen both in its positive and negative light.

Following several authors of this book (Bass, Chapter Two; Conger and Kanungo, Chapter Three; House, Woycke, and Fodor, Chapter Four), I define charisma in terms of particular leadership abilities. These include the leader's ability to: articulate a captivating vision or mission in ideological terms; create and maintain a positive image in the minds of followers; show a high degree of confidence in him- or herself and his or her beliefs; set a personal example for followers to emulate; behave in a manner that reinforces the vision or mission; communicate high expectations to followers and confidence in their ability to meet such expectations; show individualized consideration toward followers and provide them with intellectual stimulation; and demonstrate a high degree of linguistic ability and nonverbal expressiveness. These abilities of a leader represent a “generic” conceptualization of charisma. However, it is the intent of this chapter to tease out the distinctive components of charisma that delineate different charismatic forms.

It should be underscored that, in accordance with Weber's example ([1924] 1947), charisma is used in a value-neutral manner. As Willner (1984, p. 12) points out, charismatic leadership is “inherently neither moral nor immoral, neither virtuous nor wicked … such questions arise only when we wish to evaluate whether a particular charismatic leader has used the relationship in the service of good or evil.”

An Overview of the Theory

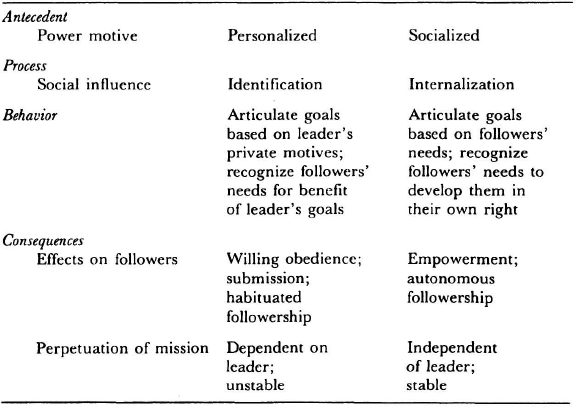

McClelland (1985), in his work on power motives, suggested two types of power: socialized and personalized. Based on such a distinction, the theory of charismatic leadership proposed in this chapter distinguishes two types of charisma: one based on the use of socialized power and the other based on the use of personalized power. The theory further suggests that these two types of charisma are exercised through different social influence processes (Kelman, 1958) and behaviors and that they result in different effects on followers and on the perpetuation of the leader's mission. Table 1 summarizes the components of the theory and their interrelationships.

Table 1. Components of Socialized and Personalized Leadership.

While this chapter distinguishes between two types of charisma—socialized and personalized—these leadership types are not mutually exclusive. It is conceivable that socialized leaders might revert to personalized leadership or personalized leaders might become socialized, depending on follower responses, situational contingencies, or a leader's personal development. In addition, a leader might simultaneously display behavior that reflects some aspects of both socialized and personalized tendencies. Although such transitional or mixed forms of charisma might be noticed in a leader's behavior, the extreme or pure types of charismatic leadership—socialized and personalized—are analyzed here for the purpose of differentiating the two faces of charisma. To achieve this purpose, the chapter is organized into six sections.

I begin by reviewing the work of McClelland and his colleagues on the power motive and deriving hypotheses concerning the two types of charismatic leadership based on a differential exercise of power. In the second section, I review Kelman's (1958) theory on social influence processes and deduce from it hypotheses concerning a differential use of social influence processes by socialized and personalized leaders. In the third section, I describe the behaviors of the two charismatic types. In the fourth section, the effects of socialized and personalized leaders on followers and on the perpetuation of the mission are outlined, citing examples from the literature to illustrate the varying effects. In the fifth section, I discuss the implications for theory on organizational and individual effectiveness. Directions for further theoretical development and research are proposed in the final section.

The Power Motive

Several scholars have postulated that charismatic leaders possess high needs for power or influence. Etzioni (1961, p. 203), for example, contends that charisma is the “ability of an actor to exercise diffuse and intensive influence over the normative orientations of other actors.” In his theory of charismatic leadership within organizations, House (1977) argues that charismatic leaders have extremely high levels of dominance and need for influence over others. In order to further our understanding of the different forms of charisma, it is instructive to examine the literature on power motivation.

McClelland and his colleagues have extensively studied the motivational aspect of power—the desire to have a strong impact on others (McClelland, 1970, 1975, 1985; McClelland and Boyatzis, 1982; McClelland and Burnham, 1976). They contend that individuals with a high need for power can be expected to take an activist role with respect to their work environment and thus more frequently attempt to influence the outcomes of important decisions.

In an examination of an individual's need for power (measured by content analysis of stories written in response to the Thematic Apperception Test [TAT]), McClelland, Davis, Kalin, and Warner (1972) found that the expression of power varied qualitatively, depending on activity inhibition. Activity inhibition is defined as the degree of restraint one feels toward the use of power. It determines whether power is expressed in socialized and controlled ways or in self-aggrandizement and impulsive aggressiveness (McClelland, 1985, p. 302).

More specifically, the socialized face of power (high need for power and high activity inhibition) is in theory characterized by efforts to assist organizational members in formulating higher-order, transcendent goals and by instilling in them a sense of power to pursue such goals. The power drive is “socialized” in the service of others. In contrast, the personalized face of power (high need for power and low activity inhibition) is characterized by the exertion of personal dominance or by seeking to “win out” over adversaries. Life is seen as a zero-sum game; power is used for personal gain or impact.

Research supporting the distinction between high and low activity inhibition is presented by McClelland. In a 1975 study, he found that individuals with greater needs for power than for affiliation but with a highly inhibited sense of power exhibited behavior characterized by respect for institutional authority, discipline, self-control, caring for others, demonstration of public concern, and a strong sense of justice. Correlations between the need for power and the presence of these behaviors with individuals high in activity inhibition ranged from .23 to .48. In contrast, for individuals low in activity inhibition, correlations were either insignificant or negative, ranging from .07 to –.35.

A longitudinal test comparing what McClelland describes as the “leadership motive pattern” (moderate to high need for power, low need for affiliation, and high activity inhibition) with long-term management success at AT&T further supports the differential effects of activity inhibition (McClelland and Boyatzis, 1982). The results revealed that managers in nontechnical jobs who possessed the leadership motive pattern upon entry into management (in comparison with nontechnical managers who did not possess this pattern) had significantly higher levels of advancement after eight and sixteen years of experience. No correlation was found between the leadership motive pattern and the level of promotion attained for technical managers.

Other studies have provided consistent support for the positive association between this leadership motive pattern and management success. For instance, McClelland and Burnham (1976) found that the subordinates of managers characterized by this pattern had higher morale and hence better sales performance than did subordinates of managers with other motive patterns. In another study, Winter (1979) reported that the leadership motive pattern was associated with success for nontechnical leadership positions in the United States Navy. There was no association between the leadership motive pattern and success for high-ranking technical officers.

In summary, the theoretical formulations and supportive research evidence presented by McClelland (1985) and McClelland and Boyatzis (1982) suggest that individual expression of the power motive varies qualitatively depending on the degree of activity inhibition. Accordingly, charismatic leaders, given their high need for power, might be differentiated by a high or low degree of activity inhibition in their expression of power. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Charismatic leaders high in activity inhibition (socialized leaders) will express and satisfy their need for power through socially constructive and egalitarian behaviors.

Hypothesis 2. Charismatic leaders low in activity inhibition (personalized leaders) will express and satisfy their need for power through personally dominant and authoritarian behaviors.

Exercise of Social Influence

Given the different power motives of personalized and socialized leaders, it may be postulated that such leaders utilize different social influence processes. In his theory of attitude formation and change, Kelman (1958) describes three conceptually distinct processes of social influence: compliance or exchange, identification or affiliation, and internalization or value congruence.

Compliance occurs when individuals adopt attitudes and behaviors in order to gain specific rewards or avoid certain punishments. This induced behavior is instrumental in producing a satisfying social effect. Under this process, the power of the influencing agent is based on control of rewards and punishments.

Identification occurs when an individual accepts outside influence in order to establish or maintain a satisfying relationship with the influencing agent. Opinions adopted through identification thus are dependent on an external source and on social support. As such, they are not integrated with the individual's value system. The satisfaction derived from identification is due to the act of conforming, not the specific content of the induced behavior. According to Kelman (1958), in the identification process, the power of the influencer is based on attractiveness: The individual possesses qualities that make a continued relationship with him or her desirable.

Internalization occurs when an individual accepts the influence of another's ideas and actions because they are congruent with his or her own value system. The adopted behavior becomes part of a personal system as opposed to a social role expectation; it is independent of an external source. The satisfaction derived from internalization is due to the content of the new behavior: It is intrinsically rewarding or appropriate for the context, and therefore it is instrumental. In this case, the power of the influencing agent is based on credibility—that is, expertise or trustworthiness.

Parallels between the three social influence processes proposed by Kelman and writings on transactional, charismatic, and transformational leadership can be drawn. The social influence process of compliance appears to be associated with transactional leadership. In his incisive analysis of transactional leadership, Burns (1978) suggests that the relationship between transactional leaders and their followers is entrenched in a bargaining process. Both parties to the exchange pursue their respective purposes and maintain the relationship as long as the individual needs of leader and follower can be met through a reciprocal exchange of rewards for services provided. However, as Burns (1978, p. 20) observes, while a leadership act has occurred, it is not one that “binds leader and follower together in a mutual and continuing pursuit of a higher purpose.”

The process of identification appears relevant to charismatic leadership. According to Dow (1969, p. 315): “It [charisma] involves a distinct social relationship between leader and follower in which the leader presents a revolutionary idea, a transcendent image or ideal which goes beyond the immediate, the proximate, or the reasonable; while the follower accepts this course of action not because of its rational likelihood of success … but because of an affective belief in the extraordinary qualities of the leader. Thus the leader appeals to … the revolutionary image and his own exemplary qualities with which the follower may identify.” Dow further states (1969, p. 308): “It is this irrational bond, or identification between leader and led, that provides the follower with an opportunity for transcendence and requires the leader, in turn, to maintain the revolutionary quality of the movement.”

In accordance with Dow, other leadership scholars have argued that charisma involves strong follower identification with the leader (see Bass, Chapter Two; Downton, 1973; House, 1977; Willner, 1984). For example, in his 1976 theory of charismatic leadership, House (1977, p. 191) argues that the charismatic leader is “an object of identification by which the followers emulate the leader's values, goals, and behavior.” Downton (1973), in his incisive analysis of charismatic and inspirational leadership, contends that followers form a strong commitment to the person of the charismatic leader as revealed in their unquestioning obedience to the leader's desires, in their capacity to criticize the leader, and in their tendency to impute special powers to the leader.

The process of internalization is closely linked to the notion of transformational leadership. Burns (1978, p. 4) posits that the transformational leader “looks for potential motives in followers, seeks to satisfy higher needs, and engages the full person of the follower.” Such leaders appeal to higher-order values that encompass followers' more fundamental and enduring needs (Burns, 1978, p. 42). Accordingly, followers' goals and aspirations transcend their immediate self-interests and are focused on the collective purpose.

A similar analysis of the social influence process employed by inspirational (socialized) leaders is presented by Downton (1973). He contends that followers' willingness to accept the leader's initiatives stems from their belief that the leader shares their social philosophy. In essence, the leader represents the collective world view of his or her followers.

Regarding charismatic leadership, power motive patterns and social influence processes may be linked together as follows. For socialized leaders, the primary focus of the power motive is the communication of higher-order values: understanding of others, tolerance, and serving the common good. I would hypothesize that the primary source of social influence employed by socialized leaders is internalization, which emphasizes the value congruence of behavior. It should be noted, however, that socialized leaders probably employ identification as a secondary mode of social influence in order to gain followers' respect and trust in themselves and in the mission they espouse.

For personalized leaders, the focus of the power motive is to exert dominance or influence over others. It is therefore postulated that the primary source of social influence utilized by personalized leaders is identification, which emphasizes the social relationship with followers. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3. Socialized leaders will exert their influence primarily through the process of internalization, which emphasizes value congruence.

Hypothesis 4. Personalized leaders will exert their influence primarily through the process of identification, which emphasizes affiliation between leader and led.

Behaviors of Socialized and Personalized Leaders

Socialized and personalized leaders appear to exhibit a common core of behaviors associated with charisma, including the ability to set high expectations for followers and express confidence in their ability to meet these expectations; create and maintain a positive image in the minds of followers, peers, and superiors; provide personal examples for followers to emulate; behave in a manner that reinforces the vision; show a high degree of confidence in themselves and their beliefs; and exhibit linguistic skill and nonverbal expressiveness (Bass, 1985; Conger and Kanungo, Chapter Three; House, 1977; House, Woycke, and Fodor, Chapter Four). These charismatic behaviors create favorable perceptions on the part of followers and foster their receptivity toward the charismatic image.

However, given the employment of different power motives and social influence processes by socialized and personalized leaders, different leader behaviors may be delineated. Socialized leaders, who make followers feel stronger and more in control of their own destinies, appear to exhibit qualitatively different behaviors than do personalized leaders, who foster followers' unquestioning trust and loyal obedience. It is argued that three behaviors differentiate socialized from personalized leaders: the articulation of a captivating vision and a set of values and beliefs to which leaders want followers to subscribe; the leader's recognition of the individual needs of followers; and the intellectual stimulation of followers.

Expression of Goals and Values. Socialized leaders express goals that are follower driven—that is, they appeal to subordinates' fundamental and enduring needs. More specifically, socialized leaders articulate general and comprehensive values that reflect the felt needs, wants, and aspirations of both leaders and followers (Burns, 1978). Goals are mutual and shared. Hence, leaders and followers are bound together in the pursuit of a common purpose.

In contrast to socialized leaders, personalized leaders articulate goals that come from within themselves—that is, they are leader driven. In particular, a leader's private motives are displaced onto followers and rationalized in terms of follower interest (Burns, 1978). These personal motives may or may not coincide with follower needs; it is the leader's intention that predominates (Burns, 1978).

Since personalized leaders express their own views, not followers' views, it is likely that more radical missions that break with tradition may be espoused. Leaders are not constrained by followers' needs, aspirations, and desires; they are driven by a highly personalized vision. Accordingly, the expression of “explosively novel” innovations and solutions (Shils, 1965, p. 199) is more probable.

Recognition of Follower Needs. Another distinctive behavior of socialized leaders is individualized consideration: the leader's developmental and individualistic orientation toward followers (Bass, 1985). According to Bass, the leader, by recognizing the needs, aspirations, and values of followers, provides examples and assigns tasks to followers on an individual basis to help them significantly alter their abilities and motivation. Therefore, through individualized consideration, socialized leaders engage followers and help them develop in their own right (Avolio and Bass, 1987).

Personalized leaders recognize followers' wants and needs only to the degree necessary to achieve their goals. Burns (1978) argues that such leaders search for the lowest common denominator of motives among and within followers and exploit those motives for their own rather than followers' benefit. Thus, personalized leaders objectify their followers, viewing them as objects to be manipulated. Adolf Hitler provides an illustration of this depersonalization of followers. According to biographer Richard Hughes (1962, p. 266), Hitler saw the universe as containing no persons other than himself—only things. Personalized leaders appeal to follower wants and needs not for developmental purposes but to advance their own purposes.

Intellectual Stimulation. According to Burns (1978) and Bass (1985), a distinctive behavior of transforming leaders is intellectual inspiration and stimulation of followers. In Burns's (1978, p. 163) view, transformational leaders in the political arena have “a capacity to conceive values or purpose in such a way that ends and means are linked analytically and creatively and that the implications of certain values for political action and governmental organization are clarified.” Therefore, a fundamental component of transformative power is the expression of analytical and normative ideas in order to change social milieus (Burns, 1978).

Bass (1985), in his discussion of transformational leadership, has extended Burns's conceptualization by explicitly recognizing the impact of the leader's intellectual creativity on followers' thinking. According to Bass, intellectual stimulation encompasses the leader's ability to suggest creative, novel ideas that result in a discrete leap in the followers' conceptualization, comprehension, and discernment of the nature of problems and their solutions. Avolio and Bass (1987) contend that the transformational leader attempts to instill in followers the ability to question not only established views but, eventually, those espoused by the leader. Through intellectual stimulation, the socialized charismatic leader coaches followers to think on their own and to develop new ventures that will further the group's goals.

Based on the above contentions, the following hypotheses are advanced with respect to the behaviors of socialized and personalized leaders:

Hypothesis 5. The behaviors of socialized leaders include articulating goals that originate from followers' fundamental wants, recognizing followers' needs in order to help them develop in their own right, and stimulating followers intellectually.

Hypothesis 6. The behaviors of personalized leaders include articulating goals that originate from leaders' private motives or intentions and recognizing followers' needs only to the degree necessary to achieve leaders' goals.

The Effects of Personalized and Socialized Charismatic Leaders

The different power motives, social influence processes, and behaviors discussed above have interesting implications with respect to their effects. Two can be readily identified: (1) in the followers' response to the leader, and (2) in perpetuation of the leader's charisma.

Followers' Response to Leaders. By expressing goals that followers want and by communicating confidence in their followers' abilities to accomplish these goals, socialized leaders strengthen and inspirit their followers to accomplish these goals (McClelland, 1975). Followers appear to become empowered and ultimately converted from followers to leaders. Graham (1982) terms this phenomenon “autonomous followership.” She suggests that preserving the capacity of followers to act autonomously is essential to maintaining the possibility of effective leadership in the future.

Writings on transformational leadership effects support this view of follower autonomy. According to Burns (1978, p. 4), the result of transformational leadership is a “relationship of mutual stimulation and elevation that converts followers into leaders and may convert leaders into moral agents.” A consistent view of follower effects is offered by Bass (1985). He proposes that transformational leaders cause followers to become more independent, self-directed, self-actualized, and altruistic.

Examples of socialized leadership effects on promoting follower autonomy and empowerment are prevalent in the literature. For instance, in an experiment designed by Winter (1967), business school students viewed a film of John F. Kennedy delivering his inaugural address. After viewing the film, the students wrote short imaginary stories to a series of TAT stimuli. Content analysis of the thoughts of students revealed that they felt strengthened, inspired, and more confident relative to a group of students exposed to a neutral control film. Using a similar methodology, consistent findings have been reported by Stewart and Winter (1976) and Steele (1977).

To cite a further example, in a case study of a charismatic superintendent in a midwestern school district facing a budgetary crisis, Roberts and Bradley (see Chapter Nine) observed that a crucial component of her charismatic power was the superintendent's ability to help people see what their skills were and to encourage them to take risks and apply their talents. According to Roberts, this socialized leader empowered or energized people by providing opportunities for personal initiative, responsibility, and participation in decision making. In this case, the leader encouraged people to use their ideas and see if they worked.

According to McClelland (1975, p. 259), personalized leaders, by force of their overwhelming persuasive powers and authority, evoke feelings of obedience or loyal submission in followers. Followers appear to surrender their power to the leader and become dependent on him or her. Graham (1982) calls this phenomenon “habituated followership”: Followers embrace their subordinate status so completely that failure to comply with the leader's requests is unthinkable.

Followers' unquestioning trust and obedience is a common theme in writings on charisma (Downton, 1973; House, 1977; Weber, [1924] 1947). In his discussion of charismatic authority, Weber (pp. 358–359) observed that charisma involves a purely personal relationship between leader and led. Due to their love, passionate devotion, and enthusiasm, followers willingly subscribe to the charismatic leader and his or her mission. In his theory of charismatic leadership, House (1977) proposes similar charismatic effects on followers: willing obedience to the leader, unquestioning acceptance of the leader, loyalty to and affection for the leader, identification with and emulation of the leader, and trust in the correctness of the leader's beliefs.

Illustrations of the effects of personalized leaders in creating follower dependence are observed in the literature. For example, Smith and Simmons (1983) give a detailed account of leader effects on followers in a new facility for emotionally disturbed children. The medical director, labeled by these investigators as charismatic, had a personally powerful presence and captivating dream of an ideal service organization. Interviews with new staff members revealed that a compelling force in their joining the medical facility was the opportunity to work with the director, who had such a clear vision of their organization's future. In delegating program planning to his clinical staff, the director, however, demanded control. When action plans were proposed by the staff, the director often vetoed them because they did not meet his vision. Accordingly, he fostered dependency and compliance among his clinical staff leading to an avoidance of needed confrontations and to an undermining of the staffs capacity and willingness to take initiative. Ultimately, the staff revolted and began working to undermine him.

An in-depth analysis of the strategies employed by the Reverend Jim Jones to foster an extraordinary degree of psychological submission among his followers is presented by Johnson (1979). Jim Jones used several means to strengthen his position of power and thereby create follower dependence: Members were required to sever their ties with the outside (including their families), contribute all their resources to the group, and migrate to an isolated environment in Guyana. Accordingly, followers became highly dependent on their leader for meeting their social, emotional, and material needs. Jim Jones's unwillingness to allow followers to be individualistic precluded their growth toward autonomy. Rather, through his actions, Jim Jones developed an adoring and totally compliant fellowship (Rutan and Rice, 1981).

The preceding theoretical arguments and illustrations lead to the following hypotheses regarding socialized and personalized effects on followers:

Hypothesis 7. Socialized leaders, by strengthening and inspiriting their followers to accomplish higher-order goals, create follower autonomy and empowerment.

Hypothesis 8. Personalized leaders, by evoking feelings of obedience and loyal submission in followers, create follower dependence and conformity.

Perpetuation of Charisma. For each social influence process, Kelman (1958) has described the conditions under which it manifests. He contends that behavior through identification occurs when an individual's relationship to the influencing agent is salient. As noted earlier, behavior adopted through identification not only is tied to an external source (that is, the influencing agent), but it also depends on social support. It is further argued that if a satisfying self-defining relationship is not maintained, identification will be discontinued. The effect of identification on an individual's responses is consistent with Weber's ([1924] 1947) notion of charismatic authority. As Weber notes (pp. 358–359), if charismatic leaders fail to benefit their followers, their charismatic authority will likely disappear.

These conceptual arguments have implications for the perpetuation of the personalized leader's charisma. Specifically, continuing identification with the personalized leader depends on the maintenance of a satisfying relationship with the leader. If this condition is not met, the potency of the ideas and actions espoused by personalized leaders and their effects on followers will decline.

According to Kelman (1958), behavior through internalization occurs under conditions when values are perceived to be shared and relevant regardless of the salience of the relationship with the influencing agent. As Kelman (1958) observes, if individuals change their perceptions of the conditions for value maximization, the induced response will be extinguished. This suggests that followers' accomplishment of a mission is independent of the leader's presence. Accordingly, the potency of ideas and actions espoused by the socialized leader should be perpetuated given the continuing relevance of the mission for the followers.

From the above conceptual arguments, the following hypotheses are proposed regarding the perpetuation of charisma:

Hypothesis 9. The potency of ideas and actions espoused by the socialized leader should be perpetuated beyond the tenure of the leader given the continued meaningfulness of the values for followers.

Hypothesis 10. The potency of ideas and actions espoused by the personalized leader will only be perpetuated given the maintenance of a satisfying relationship between leader and follower. If this relationship is attenuated, then the potency of the personalized leader will decline.

Implications of Socialized and Personalized Leadership for Organizational and Individual Effectiveness

The theory of socialized and personalized charismatic leadership developed in this chapter has important implications for organizational effectiveness and individual well-being. The functional and dysfunctional consequences of these leaders are briefly outlined below.

Personalized Leadership. From an organizational perspective, personalized leaders may have both desirable and deleterious effects. In times of crisis, for example, personalized leaders might be very beneficial for organizational health. By espousing a radical vision that offers a possible functional solution for overcoming distressful conditions, personalized leaders may serve as a source of organizational renewal and redirection. Moreover, by virtue of their overwhelming presence and dominance, these leaders can harness the energies of followers to single-mindedly devote themselves to the cause and to the leader. Such sustained efforts on the part of followers may speed organizational revitalization.

Beyond the crisis phase, however, the long-term effectiveness of an organization may be jeopardized by personalized leaders. For example, in order to perpetuate their charismatic image, these leaders may create stressful circumstances. They may subvert institutional innovations in order to pursue their own course of action or propound values that are personally based, not organizationally derived. Therefore, in the long run, personalized leaders may represent a very unsettling and disruptive force in the organization, inappropriate for the stability and continuity of the existing structure, systems, and culture.

From an individual perspective, personalized leaders appear to have negative effects on followers' personal growth and career development. By fostering followers' dependence, conformity, and obedience, personalized leaders undermine followers' motivation and ability to challenge existing views, develop independent perspectives, and undertake new ventures. In the short run, followers' capacity for independent thought and action may be impaired. Ultimately, the personalized leaders' effort to win devotion and commitment of followers may turn to the tyranny of thought control and brainwashing.

Socialized Leadership. Adopting an organizational view, socialized leaders appear to have a positive effect on organizational life. By expressing followers' wants, needs, and aspirations, socialized leaders represent a force for evolutionary, not revolutionary, changes that are aligned with organizational interests. In addition to serving as a positive force for change, socialized leaders raise the level of consciousness of human conduct and the ethical aspirations of both leader and led (Burns, 1978). Accordingly, socialized leaders may transform and elevate the values and conduct of the organization.

Socialized leaders also appear to enhance individual effectiveness. By encouraging followers to think on their own, to question established ways of doing things, and to focus on their collective purpose, socialized leaders mobilize their followers' potential for the independent pursuit of activities, creative action, and personal development. Accordingly, these leaders may develop a cadre of possible future leaders, not followers (Burns, 1978). Therefore, the pool of talent necessary for executive succession may be expanded.

Toward the Future: Implications for Theoretical Development and Research

In this chapter, I have proposed a theory to explain the variances we see in charismatic leaders. However, further theoretical developments are clearly required. As discussed in the introduction, transitions between socialized and personalized leadership are conceivable. In addition, leaders may manifest both socialized and personalized behaviors, utilize a variety of social influence processes, and obtain a range of follower responses. For example, a personalized leader might utilize all three influence processes (compliance, identification, and internalization) with primary emphasis on identification. Given certain circumstances, a different influence process might be employed as a secondary mode.

Further theoretical development is also needed with respect to other predispositions (in addition to need for power) that distinguish socialized and personalized leaders. For example, the level of socioemotional maturity or of generalized self-efficacy may differ for these leadership forms. As well, personality characteristics that predispose followers to support or oppose leaders need to be explored. For instance, are followers with an external locus of control, a low need for dominance, and low tolerance for ambiguity more receptive to a personalized leader than are followers with an internal locus of control, a high need for dominance, and high tolerance for ambiguity?

Situational contingencies that might influence followers' receptiveness to and acceptance of socialized and personalized leaders need to be determined. Perhaps followers may be more willing to embrace a personalized leader during times of crisis. As several leadership scholars have observed (Halpin, 1954; Korten, 1968; Mulder, Ritsema van Eck, and de Jong, 1970; Mulder and Stemerding, 1963; Torrance, 1954; Tucker, 1970; Weber, [1924] 1947; Ziller, 1955), people in need of deliverance from distress more easily respond with great emotional fervor to a leader who offers or strengthens faith in that possibility. A state of acute distress predisposes people to perceive extraordinary qualities and to follow with enthusiastic loyalty a leader offering salvation from distress (Tucker, 1970; Weber, [1924] 1947). Under these circumstances, personalized leaders who exert personal dominance and authority may be more appropriate from the followers' perspective. However, to speculate, as crisis subsides or pressures abate, receptivity to the personalized leader may decline.

It also seems probable that socialized leaders emerge during times of crisis. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, for example, won the American presidency at the nadir of the nation's worst depression. However, in contrast to personalized leadership, there may be more opportunities for socialized leadership in less intense situational contexts. For example, House and Singh (1987) contend that egalitarian (socialized) charismatic leaders may be appropriate for situations requiring creativity, adaptability to changing conditions and uncertain environments, extraordinarily high initiative, and personal assumption of responsibility on the part of followers.

Another area for further exploration is the emotional responses of followers to socialized and personalized leadership. Do both leadership forms equally inspire love and hatred in followers? Or are personalized leaders, given their focus on personal dominance, more likely to polarize followers, commanding allegiance, reverence, and loyalty among supporters and generating hatred, animosity, and fear among opponents? A related issue to be addressed is the basis for follower commitment to the leader. For instance, followers' willingness to accept personalized leaders' initiatives, which may be interpreted as a manifestation of devotion to the leader, might be a facade rooted in followers' fear of punishment (Downton, 1973, p. 77).

In addition to theoretical developments, testing of the hypotheses advanced in this chapter is required. Three research methodologies can be proposed for such testing. First, following the methodology used in Chapter Four, the motivational imagery in the speeches of charismatic leaders could be content analyzed for low and high activity inhibition. Second, field studies might be conducted to test the proposed theory. Using Bass's Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, profiles of charismatic (personalized) and transformational (socialized) leaders could be obtained. To determine the differential use of social influence processes by these leaders, followers' identification and internalization could be measured using O'Reilly and Chatman's (1986) instrument. Third, laboratory experiments could be designed in which confederate leaders would be trained to display either personalized or socialized behaviors. Their effects on their followers' task performance, task identification, and satisfaction and the followers' relationship with the leader could then be measured. The convergence of findings from these multiple methodologies would strengthen the validity of the theory's propositions.

Conclusion

A significant gap in our current thinking about charisma is the lack of delineation between different forms of charisma. To date, a wide range of leadership has been captured by the generic label “charisma.” However, in order to aid scientific inquiry, it is critical for organizational scholars to distill the elements that differentiate leaders as disparate as Mahatma Gandhi, Adolf Hitler, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jim Jones, and Martin Luther King, Jr. To that end, this chapter has attempted to distinguish between socialized and personalized leaders with respect to their power motives, social influence processes, behaviors, and effects on followers and on the perpetuation of charisma. By differentiating these two forms of charismatic expression, the possibilities and limitations for organizational and individual effectiveness are highlighted. It is hoped that by identifying socialized and personalized leaders in advance we can eventually enhance the effectiveness of such leaders and minimize their dysfunctional outcomes in organizations.

References

Avolio, B. J., and Bass, B. M. “Charisma and Beyond.” In J. G. Hunt (ed.), Emerging Leadership Vistas. Elmsford, N.Y.: Pergamon Press, 1987.

Bass, B. M. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press, 1985.

Bennis, W., and Nanus, B. Leaders: The Strategies for Taking Charge. New York: Harper & Row, 1985.

Burns, J. M. Leadership. New York: Harper & Row, 1978.

Clark, B. R. The Distinctive College: Antioch, Reed and Swarthmore. Hawthorne, N.Y.: Aldine, 1970.

Dow, T. E. “The Theory of Charisma.” Sociological Quarterly, 1969, 10, 306–318.

Downton, J. V. Rebel Leadership: Commitment and Charisma in the Revolutionary Process. New York: Free Press, 1973.

Etzioni, A. A Comparative Analysis of Complex Organizations. New York: Free Press, 1961.

Graham, J. W. “Leadership: A Critical Analysis.” Paper presented at annual meeting of the Academy of Management, New York, Aug. 1982.

Halpin, A. W. “The Leadership Behavior and Combat Performance of Airplane Commanders.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1954, 49, 19–22.

House, R. J. “A 1976 Theory of Charismatic Leadership.” In J. G. Hunt and L. L. Larson (eds.), Leadership: The Cutting Edge. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1977.

House, R. J., and Singh, J. V. “Organizational Behavior: Some New Directions for I/O Psychology.” Annual Review of Psychology, 1987, 38, 669–718.

Howell, J. M. “Charismatic Leadership: Effects of Leadership Style and Group Productivity on Individual Adjustment and Performance.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Faculty of Commerce and Business Administration, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 1986.

Howell, J. M., and Frost, P. J. “A Laboratory Study of Charismatic Leadership.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, forthcoming.

Hughes, R. The Fox in the Attic. New York: Harper & Row, 1962.

Johnson, D. P. “Dilemmas of Charismatic Leadership: The Case of the People's Temple.” Sociological Analysis, 1979, 40, 315–323.

Kelman, H. C. “Compliance, Identification, and Internalization: Three Processes of Attitude Change.” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 1958, 2, 51–60.

Korten, D. C. “Situational Determinants of Leadership Structure.” In D. Cartwright and A. Zander (eds.), Group Dynamics: Research and Theory. New York: Harper & Row, 1968.

McClelland, D. C. “The Two Faces of Power.” Journal of International Affairs, 1970, 24, 29–47.

McClelland, D. C. Power: The Inner Experience. New York: Irvington, 1975.

McClelland, D. C. Human Motivation. Glenview, Ill.: Scott, Foresman, 1985.

McClelland, D. C., and Boyatzis, R. E. “Leadership Motive Pattern and Long-Term Success in Management.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 1982, 67, 737–743.

McClelland, D. C., and Burnham, D. H. “Power Is the Great Motivator.” Harvard Business Review, 1976, 54 (2), 100–111.

McClelland, D. C., Davis, W. N., Kalin, R., and Warner, R. The Drinking Man. New York: Free Press, 1972.

Mulder, M., Ritsema van Eck, J. R., and de Jong, R. D. “An Organization in Crisis and Non-Crisis Situations.” Human Relations, 1970, 24, 19–41.

Mulder, M., and Stemerding, A. “Threat, Attraction to Group and Need for Strong Leadership: A Laboratory Experiment in a Natural Setting.” Human Relations, 1963, 16, 317–334.

O'Reilly, C., and Chatman, J. “Organizational Commitment and Psychological Attachment: The Effects of Compliance, Identification, and Internalization on Prosocial Behavior.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 1986, 71, 492–499.

Peters, T. J., and Waterman, R. H., Jr. In Search of Excellence. New York: Harper & Row, 1982.

Roberts, N. C. “Transforming Leadership: Sources, Process, Consequences.” Paper presented at annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Boston, Aug. 1984.

Rutan, J. S., and Rice, C. A. “The Charismatic Leader: Asset or Liability?” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 1981, 18, 487–492.

Shils, E. A. “Charisma, Order, and Status.” American Sociological Review, 1965, 30, 199–213.

Smith, K. K., and Simmons, V. M. “A Rumpelstiltskin Organization: Metaphors on Metaphors in Field Research.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 1983, 28, 377–392.

Steele, R. S. “Power Motivation, Activation, and Inspirational Speeches.” Journal of Personality, 1977, 45, 53–64.

Stewart, A. J., and Winter, D. G. “Arousal of the Power Motive in Women.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1976, 44, 495–496.

Tichy, N. M., and Devanna, M. A. The Transformational Leader. New York: Wiley, 1986.

Torrance, E. P. “The Behavior of Small Groups Under Stress Conditions of Survival.” American Sociological Review, 1954, 19, 751–755.

Trice, H. M., and Beyer, J. M. “Charisma and Its Routinization in Two Social Movement Organizations.” Research in Organizational Behavior, 1986, 8, 113–164.

Tucker, R. C. “The Theory of Charismatic Leadership.” In D. A. Rustow (ed.), Philosophers and Kings: Studies in Leadership. New York: Braziller, 1970.

Weber, M. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. (A. M. Henderson and T. Parsons, trans.; T. Parsons, ed.) New York: Free Press, 1947. (Originally published 1924.)

Willner, A. R. The Spellbinders: Charismatic Political Leadership. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1984.

Winter, D. G. “Power Motivation in Thought and Action.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, Harvard University, 1967.

Winter, D. G. Navy Leadership and Management Competencies: Convergence Among Tests, Interviews, and Performance Ratines. Boston: MA, McBer, 1979.

Ziller, R. C. “Leaders' Acceptance of Responsibility for Group Action Under Conditions of Uncertainty and Risk.” American Psychologist, 1955, 10, 475–476.