Economic Activity in the CIS Region

Overview

One of the clearest failures of the CIS has been on the economic front. Although the member states pledged cooperation, things began to break down early on. By 1993, the ruble zone collapsed, with each state issuing its own currency. In 1993 and 1994, eleven CIS states ratified a Treaty on an Economic Union, in which Ukraine joined as an associate member. A free-trade zone was proposed in 1994, but by 2002 it still had not yet been fully established. In 1996 four states, including Russia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan, created a Customs Union,1 but others refused to join. All these efforts were designed to increase trade, but, due to several factors, trade among CIS countries has lagged targeted figures. More broadly speaking, economic cooperation has suffered because states had adopted economic reforms and programs with little regard for the CIS and have put more emphasis on redirecting their trade to neighboring European or Asian states.

Economic Challenges

Per Marek Dabrowski,2 a scholar and Professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow and Fellow at CASE—Centre for Social and Economic Research in Warsaw, the period of fast economic growth and relative macroeconomic stability in the CIS seems to be over. The collapse of the Russian ruble, expected recession in Russia, the stronger U.S. dollar and lower commodity prices have negatively affected the entire region through trade, labor remittance, and financial-market channels, resulting in negative expectations and leading to either substantial depreciation of national currencies, or decline in countries international reserves, or both. This means that the EU’s entire eastern neighborhood faces serious economic, social, and political challenges coming from weaker currencies, higher inflation, decreasing export revenues and labor remittances, net capital outflows and stagnating or declining GDP.

The currency crisis started in Russia and Ukraine during 2014 because of the combination of global, regional and country-specific factors. Among the latter, the ongoing conflicts between the two countries and the associated U.S. and EU sanctions against Russia have played the most prominent role. At the end of 2014 and in early 2015, the currency crisis spread to Russia and Ukraine’s neighbors.

The gradual depreciation of the ruble against both the euro and U.S. dollar, as depicted in Figure 2.1, started in November 2015, before the Russian-Ukraine conflict emerged and when oil prices were high. The depreciation intensified in March and April 2014, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the first round of U.S. and EU sanctions against Russia. Between May and July 2014, the ruble partly regained its previous value.

The depreciation trend, however, returned in the second half of July 2014. Its pace increased in October with a culmination in mid-December 2014, as also depicted in Figure 2.1. After a massive intervention on the foreign exchange market and the adoption by Russia of other anticrisis measures the situation stabilized for a while. However, depreciation started again in January 2015, boosted by Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s downgrading of Russia’s credit rating, and the subsequent escalation of the Donbass3 conflict in the Ukraine.

Figure 2.1 Ruble exchange rate against the euro and dollar, 2013–15

Source: Central Bank of Russia, http://cbr.ru/eng/currency_base/dynamics.aspx

Figure 2.2 Russia’s international reserves in $ billions, 2013–14

Source: Central Bank of Russia, http://cbr.ru/eng/hd_base/default.aspx?Prtid=mrrf_m

Cumulatively, between the end of November 2015 and end of 2014, Russia lost in the region $130 billion of its international reserves, as shown in Figure 2.2, which resulted from a large-scale capital outflow estimated to exceed $150 billion in 2014. Nevertheless, Russia continues to have a sizeable current account surplus. In the first half of January 2015, the reserves decreased further by about $7 billion.

Economies at War

This currency crisis challenges in Russia and in the CIS (more on this in the next section) is in fact a result of a much bigger threat to the global economy, often dubbed by economists at large because of currency wars. For the past few years, at least since 2010, government officials from the G7 economies have been very concerned with the potential escalation of a global economic war. Not a conventional war, with fighter jets, bullets, and bombs, but instead, a “currency war.” Finance ministers and central bankers from advanced economies worry that their peers in the G20, which also include several emerging economies, may devalue their currencies to boost exports and grow their economies at their neighbors’ expense.

Brazil led the charge, being the first emerging economy to accuse the United States of instigating a currency war in 2010, when the U.S. Federal Reserve bought piles of bonds with newly created money. From a Chinese perspective, with the world’s largest holdings of U.S. dollar reserves, a U.S. lead currency war based on dollar debasement is an American act of default to its foreign creditors no matter how you disguise it. So far the Chinese have been more diplomatic, but their patience is wearing thin.

These two countries are not alone, as depicted in Figure 2.3, several other emerging markets, such as Saudi Arabia, Korea, Russia, Turkey and Taiwan have also been impacted by a weak dollar. That “quantitative easing” (QE) made investors flood emerging markets with hot money in search of better returns, which consequently lifted their exchange rates. But Brazil was not alone, as Japan’s Shinzo Abe, the new prime minister, has also reacted to the QEs in the United States and pledged bold stimulus to restart growth and vanquish deflation in the country.

As advanced economies, like the first three largest world economies—United States, China, and Japan respectively—try to kick-start their sluggish economies with ultralow interest rates and sprees of money printing, they are putting downward pressure on their currencies. The loose monetary policies are primarily aimed at stimulating domestic demand. But their effects spill over into the currency world.

Figure 2.3 Emerging market currencies inflated by weak dollar

Source: Thompson Reuters Datastream.

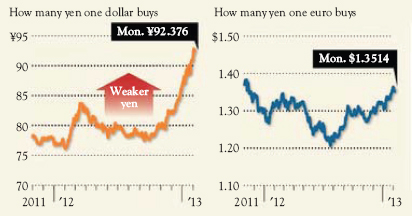

Japan is facing charges that it is trying first and foremost to lower the value of its currency, the yen, to stimulate its economy and get the edge over other countries. The new government is trying to get Japan, which has been in recession, moving again after a two-decade bout of stagnant growth and deflation. Hence, it has embarked on an economic course it hopes will finally jump-start the economy. The government pushed the Bank of Japan to accept a higher inflation target, which has triggered speculation the bank will create more money. The prospect of more yen in circulation has been the main reason behind the yen’s recent falls to a 21-month low against the dollar and a near 3-year record against the euro.

Since Shinzo Abe called for a weaker yen to bolster exports the currency has fallen by 16 percent against the dollar and 19 percent against the euro. As the yen falls, its exports become cheaper, and those of Asian neighbors South Korea and Taiwan, as well as those countries further afield in Europe, become relatively more expensive. As depicted in Figure 2.4, central banks in the United States and Japan have flooded their economies with liquidity since mid-2012 into 2015, causing the yen and the dollar to weaken against other major currencies.

Figure 2.4 Central banks in the United States and Japan have flooded their economies with liquidity

Source: WSJ Market Data Group.

In our opinion, common sense could prevail, putting an end to the dangerous game of beggar (and blame) thy neighbor. After all, the International Monetary Fund was created to prevent such races to the bottom, and should try to broker a truce among foreign exchange competitors. The critical issues in the United States, as well as China and Japan, stem from minimally a blatantly ineffective public policy, but overridingly a failed and destructive economic policy. These policy errors are directly responsible for the opening salvos of the currency war clouds now looming overhead.4

So far, Europe has felt the impact of the falling yen the most. At the height of the Eurozone’s financial crisis in 2012, the euro was worth $1.21, which was potentially benefitting big exporters like BMW, AUDI, Mercedes, or Airbus. However, at the time of these writing, December 2015, the euro is at $1.38 even though the Eurozone is still the laggard of the world economy.

Across the 17-strong euro area a recovery has got under way following a double-dip recession lasting 18 months, but it is a feeble one. For 2015 GDP, will continue to fall by 0.4 percent (after declining by 0.6 percent in 2012), but it is expected to rise by 1.1 percent in 2014.5 A rise in the value of euro, which is also partly to do with the diminishing threat of a collapse of the currency, will do little to help companies in the Eurozone—and will hardly help getting it growing again.

Chinese policy makers reject the conventional thinking proposed by advanced economies. How about the yen’s extraordinary rise over the last 40 years, from JPY360 against the dollar at the beginning of the 1970s to about JPY102 today?6 Not to mention that despite this huge appreciation, Japan’s current account surplus has only got bigger, not smaller. They could also argue that the United States’ prescription for China’s economic rebalancing, a stronger currency and a boost to domestic demand, was precisely the policy followed by the Japanese in the late-1980s, leading to the biggest financial bubble in living memory and the 20-year hangover that followed.

Furthermore, the demand by the United States, which is backed by the G7 for a renminbi revaluation, is, in our view, a policy of the United States’ default. During the Asian crisis in 1997 through 1998, advanced economies, under the auspices of the IMF, insisted that Asian nations, having borrowed so much, should now tighten their belts. Shouldn’t advance economies be doing the same? In addition, Chinese manufacturing margins are so slim that significant change in exchange rates could wipe them out and force layoffs of millions of Chinese. As it is, labor rates are already climbing in China, further squeezing margins. Lastly, a revaluation of the yuan would only push manufacturing to other cheaper emerging markets, such as Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Bangladesh, and other lower-paying nations without improving the advanced economies trade deficits.

Notwithstanding, some G7 policy makers believe these grumbles are overdone; arguing that the rest of the world should praise the United States and Japan for such monetary policies, suggesting the Eurozone should do the same. The war rhetoric implies that the United States and Japan are directly suppressing their currencies to boost exports and suppress imports, which in our view is a zero-sum game, which could degenerate into protectionism and a collapse in trade.

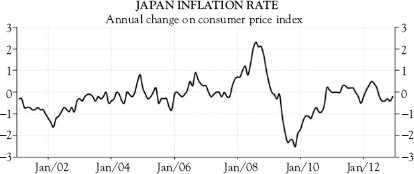

These countries, however, do not believe such currency devaluation strategy will threaten trade. Instead, their belief seems to be that as central banks continue to lower their short-term interest rate to near zero, exhausting their conventional monetary methods, they must employ unconventional methods, such as QE, or trying to convince consumers that inflation will raise. Their goal with these actions is to lower real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. If so, inflation should be rising in Japan and in the United States, which as per Figure 2.5 it is.

As Figure 2.5 also shows, over the past decade, Japan has seen the consumer price index (CPI) for most periods hover just below the zero-percent inflation line. The notable exceptions were in 2008, when inflation rose as high as 2 percent, and in late 2009, when prices fell at close to a 2 percent rate. The rise in inflation coincided with a crash in capital spending. The worst period of deflation preceded an upturn. Of course, the earlier figure does not provide enough data to infer causal effects, but it seems, however, that the relationship between growth and Japan’s mild deflation may be more complicated than the Great Depression-inspired deflationary spiral narrative suggests. The principal goal of this policy was to stimulate domestic spending and investment, but lower real rates usually weaken the currency as well, and that in turn tends to depress imports. Nevertheless, if the policy is successful in reviving domestic demand, it will eventually lead to higher imports.

Figure 2.5 Japan’s inflation rate has been climbing since 2010 because of economic stimulus

Source: Trading Economics,7 Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

At least that’s how the argument goes. The IMF concluded that the United States’ first rounds of QE boosted its trading partners’ output by as much as 0.3 percent. The dollar did weaken, but that became a motivation for Japan’s stepped-up assault on deflation. The combined monetary boost on opposite sides of the Pacific has been a powerful elixir for global investor confidence, if anything, to move hot money onto emerging markets where the interests were much higher than at advanced economies.

The reality is that most advanced economies have overconsumed in recent years. It has too many debts. But rather than dealing with those debts—living a life of austerity, accepting a period of relative stagnation—these economies want to shift the burden of adjustment on to its creditors, even when those creditors are relatively poor nations with low per capita incomes. This is true not only for Chinese but also for many other countries in Asia and in other parts of the emerging world. During the Asian crisis in 1997 through 1998, Western nations, under the auspices of the IMF, insisted that Asian nations, having borrowed too much, should now tighten their belts. But the United States doesn’t seem to think it should abide by the same rules. Far better to use the exchange rate to pass the burden on to someone else than to swallow the bitter pill of austerity.

Meanwhile, European policy makers, fearful that their countries’ exports are caught in this currency war crossfire, have entertained unwise ideas such as directly managing the value of the euro. While the option of generating money out of thin air may not be available to emerging markets, where inflation tends to remain a problem, limited capital controls may be a sensible short-term defense against destabilizing inflows of hot money. Figure 2.6 illustrates how the inflows of hot money leaving advanced economies in search of better returns on investments in emerging markets have caused these markets to significantly outperform advanced (developed) markets.

Figure 2.6 In 2009 emerging markets significantly outperformed advanced (developed) economies

Source: FTSE All-World Indices.

Currency War May Cause Damage to Global Economy

As more countries try to weaken their currencies for economic gain, there may come a point where the fragile global economic recovery could be derailed and the international financial system thrown into chaos. That’s why financial representatives from the world’s leading 20 industrial and developing nations, spent most of their time during the G20 summit in Moscow in September 2015.

In September 2011, Switzerland acted to arrest the rise of its currency, the Swiss franc, when investors, looking for somewhere safe to store their cash from the debt crisis afflicting the 17-country Eurozone, saw in the Swiss franc the traditional instrument to fulfill that role. The Swiss intervention was viewed as an attempt to protect the country’s exporters.

In our view, policy makers are focusing on the wrong issue. Rather than focus on currency manipulation, all sides would be better served to zero in on structural reforms. The effects of that would be far more beneficial in the long run than unilateral United States, China, or Japan currency action, and more sustainable. The G20 should focus on a comprehensive package centered on structural reforms in all countries, both advanced economies and emerging markets. Exchange rates should be an important part of that package, no doubt. For instance, to reduce the U.S. current-account deficits, Americans must save more. To continue to simply devalue the dollar will not be sufficient for that purpose. Likewise, China’s current-account surpluses were caused by a broad set of domestic economic distortions, from state-allocated credit to artificially low interest rates. Correcting China’s external imbalances requires eliminating these distortions as well.

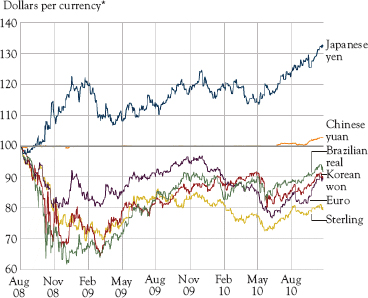

As long as policy makers continue to focus on currency exchange issues, the volatility in the currency markets will continue to escalate. It has become so worrisome that the G7 advanced economies have warned that volatile movements in exchange rates could adversely hit the global economy. Figure 2.7 provides a broad view (rebased at 100 percent on August 1, 2008) of main exchange rates against the dollar.

When it became clear that Shinzo Abe and his agenda of growth-at-all-costs would win Japan’s elections, the yen lost more than 10 percent against the dollar and some 15 percent against the euro. In turn, the dollar has also plumbed to its lowest level against the euro in nearly 15 months. These monetary debasement strategies are adversely impacting and angering export-driven countries such as Brazil, and many of the BRICS, ASEAN, CIVETS, and MENA blocs. But they also are stirring the pot in Europe. The Eurozone has largely sat out this round of monetary stimulus and now finds itself in the invidious position of having a contracting economy and a rising currency.

Figure 2.7 Exchange rates against the dollar

Source: Bloomberg.

These currency moves have shocked BRICS countries as well as other emerging-market economies, including Thailand. The G20 is clearly divided between the advanced economies—the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan, France, Canada, Italy, Germany—and emerging countries such as Russia, China, South Korea, India, Brazil, Argentina, Indonesia, and the like. Top leaders of Russia, South Korea, Germany, Brazil, and China have all expressed their concern over the currency moves, which drive up the value of their currencies and undermine the competitiveness of their exports. If they decide to enter the game, like Venezuela, which has devalued its currency by 32 percent, the world would be plunged into competitive devaluations. At the end of the day, competitive devaluations would lead to run-away inflation or hyperinflation. Nobody will win with these currency wars.

James Rickards, author of “Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisis,” expect the international monetary system to destabilize and collapse. In his views, “there will be so much money-printing by so many central banks that people’s confidence in paper money will wane, and inflation will rise sharply.8”

If policy makers truly want to stage off this currency war, then it is a matter of doing what it was done in 1985 with the Plaza Accord.9 This time, however, we will need a different version, as it will not be about the United States and the G5 of the time, in 1985. It must be an Asian Plaza Accord under the support and auspices of the G20. It must be about the Asia export led and mercantilist leadership agreeing amongst them. The chances of this happening, of advanced economies seeing the requirement for it, or these economies relinquishing its powers in any measurable fashion are not at all possible under the current political gamesmanship presently being played.

Currency War Also Means Currency Suicide

—Special contribution by Patrick Barron10

What the media calls a “currency war,” whereby nations engage in competitive currency devaluations to increase exports, is really “currency suicide.” National governments persist in the fallacious belief that weakening one’s own currency will improve domestically produced products’ competitiveness in world markets and lead to an export driven recovery. As it intervenes to give more of its own currency in exchange for the currency of foreign buyers, a country expects that its export industries will benefit with increased sales, which will stimulate the rest of the economy. So, we often read that a country is trying to “export its way to prosperity.”

Mainstream economists everywhere believe that this tactic also exports unemployment to its trading partners by showering them with cheap goods and destroying domestic production and jobs. Therefore, they call for their own countries to engage in reciprocal measures. Recently Martin Wolfe in the Financial Times of London and Paul Krugman of The New York Times both accuse their countries’ trading partners of engaging in this “beggar-thy-neighbor” policy and recommend that England and the United States respectively enter this so-called “currency war” with full monetary ammunition to further weaken the pound and the dollar.

I, Patrick, am struck by the similarity of this currency-war argument in favor of monetary inflation to that of the need for reciprocal trade agreements. This argument supposes that trade barriers against foreign goods are a boon to a country’s domestic manufacturers at the expense of foreign manufacturers.

Therefore, reciprocal trade barrier reductions need to be negotiated, otherwise the country that refuses to lower them will benefit. It will increase exports to countries that do lower their trade barriers without accepting an increase in imports that could threaten domestic industries and jobs. This fallacious mercantilist theory never dies because there are always industries and workers who seek special favors from government at the expense of the rest of society. Economists call this “rent seeking.”

Contagion Effect: The Spreading of the Crisis to CIS Member Countries

Since November 2014, the crisis has spread to number of former Soviet Union countries, especially Belarus, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Moldova. It also affected, to a lesser extent, some countries in central and the CIS. The crisis-contagion mechanisms worked through several channels: Decreasing trade and deteriorating terms of trade with Russia, decreasing remittances from migrants working in Russia and, most importantly, the devaluation expectations of households and financial market players. Those former Soviet Union countries, for which Russia is an important trade partner, could not sustain continuation of the nominal appreciation of their currencies in relation to the ruble.

In addition, during the December 2014 phase of the CIS currency crisis a degree of contagion effect was visible on foreign exchange markets in central Europe, where currencies with flexible exchange rates depreciated against both the dollar and the euro. This affected the Hungarian forint, Serbian dinar, Polish zloty, Romanian leu, and Turkish lira. However, because of the limited trade and financial links between these countries and Russia and Ukraine, investors’ negative reactions to these currencies were rather short-lived.

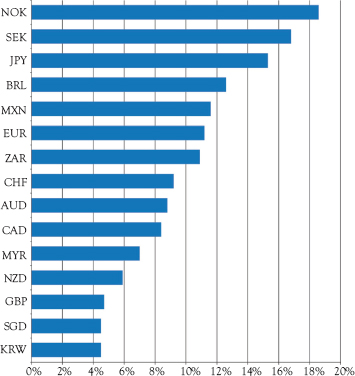

As discussed in the previous section, among the global factors that contributed to the CIS currency crisis, U.S. monetary policy seems to have played an important role. Since mid-2015, the expectation of the phasing down of QE 3, which eventually happened in October 2014, and more recently, expectations of an increase in the U.S. Federal Fund Rate in 2015,11 has led to tighter global liquidity conditions. This could not be fully compensated for by simultaneous monetary policy easing in the euro area and Japan because of the much smaller size of financial markets in euro and yen. As result, net capital inflows into emerging-market economies decreased, growth in the latter decelerated and commodity prices started to fall12 (see Feldstein, 2014 and Frankel 2015, on the effects of U.S. monetary tightening on oil and commodity prices). During 2014, as depicted in Figure 2.8, especially in the fourth quarter, the dollar appreciated against most currencies with flexible exchange rates.

Figure 2.8 Depreciation against the dollar, in percent, December 2015 to December 2014, selected currencies

Source: U.S. Federal Reserve Board, http://federalreserve.gov/releases/g5/current/default.htm

1 A group of countries that have agreed to charge the same import duties as each other and usually to allow free trade between themselves.

2 Dabrowski, M. 2015. “It is not just Russia: current crisis in the CIS.” Bruegel Policy Contribution, Issue 2015/01, February 2015, http://bruegel.org/wpcontent/uploads/imported/publications/pc_2015_01_CIS_.pdf, last accessed on 01/10/2016.

3 The War in Donbass, also known as the War in Ukraine or the War in Eastern Ukraine, is an armed conflict in the Donbass region of Ukraine. From the beginning of March 2014, demonstrations by pro-Russian and anti-government groups took place in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine, together commonly called the “Donbass,” in the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution and the Euromaidan movement.

4 Our opinion expressed here is from the point of you of international trade and currency exchange as far as it affects international trade, and not from the geopolitical and economic aspects of the issue. We approach the issue of currency wars not from the theoretical, or even simulation models undertaken from behind a desk in an office, but from the point of view of practitioners engaged in international business and foreign trade, on the ground, in four different countries.

5 The Economist’s Writers 2015. “Taking Europe’s pulse.” The Economist, 11/05/2015. http://economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2015/11/europeaneconomy-guide. Last accessed on 12/13/2015.

6 As of December 2015.

7 http://tradingeconomics.com, last accessed on 09/12/2015.

8 Francesco, G. 2015. “Currency War Has Started.” The Wall Street journal, 02/04/2015. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424127887324761004578283684195892250. Last accessed on 12/13/2015.

9 The Plaza Accord was an agreement between the governments of France, West Germany, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom, to depreciate the U.S. dollar in relation to the Japanese yen and German Deutsche Mark by intervening in currency markets. The five governments signed the accord on September 22, 1985 at the Plaza Hotel in New York City.

10 Patrick Barron is a private consultant in the banking industry. He teaches in the Graduate School of Banking at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and teaches Austrian economics at the University of Iowa, in Iowa City, where he lives with his wife of 40 years. We recommend you to visit his blog at http://patrickbarron.blogspot.com/ or contact him at [email protected].

11 Darvas, Z. 2014. “Central Bank Rates Deep in Shadow.” Bruegel blog, http://bruegel.org/nc/blog/detail/article/1497-central-bank-rates-deep-in-shadow/

12 Feldstein, M. 2014. “The Geopolitical Impact of Cheap Oil.” Project Syndicate, 26 November, http://project-syndicate.org/commentary/oil-prices-geopolitical-stability-by-martin-feldstein-2014-11;Frankel,J.2014. “The Euro Crisis: Where to From Here?,” Faculty Research Working Paper Series, Harvard Kennedy School, RWP15-015.