The Impact of the Global Economic Crisis on CIS Economies

Overview

Emerging market economies, including the CIS countries, were major beneficiaries of the economic boom before 2007. Nonetheless, they have become victims of the global financial crisis. Their future development depends, to a larger extent, on global economic prospects. Today the global economy and the European economy are much more integrated and interdependent than they were 10 or 20 years ago. Every country must recognize its limited economic sovereignty and must be prepared to deal with the consequences of global macroeconomic fluctuations.

Overall, the CIS countries, excluding Russia, have been generally badly affected by the global financial crisis and economic downturn in 2008. The impact on growth has varied but weak demand for commodities and exports, as well as the drying-up of international liquidity had significant repercussions. CIS countries were particularly affected by commodity prices, which fell because of slowing global demand. Ukraine, for instance, is highly dependent on steel. Similarly, oil-rich central Asian countries such as Kazakhstan were affected in a similar way.

As a result of the global financial crisis, emerging and developing economies across the globe experienced a sharp slowdown in output growth. In aggregate, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth in emerging and developing economies fell from 8.3 percent in 2007 to 6.1 percent in 2008 and just 1.2 percent in 2015 (IMF 2016). Commodity concentration was a problem for many of the CIS and is the result of their minimal production and export of manufactured goods and heavy reliance on commodity exports, primarily oil and gas.

Global Economic Crisis Impact on CIS Economies

On average, the CEE region experienced a smaller output decline than the Euro area and the entire EU while the CIS, especially its European part, contracted more dramatically. However, there was a deep differentiation within each country group. Looking globally, richer countries, which are more open to trade and in which the banking sector plays a larger role and which rely more on external financing, suffered more than less-sophisticated economies, which are less dependent on trade and credit. With some exceptions, the previous good growth performance helped rather than handicapped countries in the CIS regions in the crisis year of 2009.

CIS countries which had no EU membership perspective, or even close association, benefited from the global commodity boom. All post-communist economies gained from the previous decade of painful economic reforms and restructuring. But with the inception of the global financial crisis, liquidity and credit dried up, capital started to leave the CIS region and fly back to the main financial centers, mostly the U.S. Stock markets and commodity prices declined, although there was almost a 1-year time mismatch between the collapse of these two asset markets, risk premia for both sovereign and private borrowing grew dramatically, and many national currencies depreciated, especially in countries which run floating exchange rate regimes, threatening the massive insolvency of economic agents borrowing in foreign currencies.

Some countries experienced banking sector troubles. Few financial institutions in the CIS were directly affected by the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis, thanks to their comparatively small exposure to overseas assets. However, financial institutions were far from immune. Banks in Kazakhstan, Central Asia’s largest economy, were thought to be particularly badly affected as they borrowed heavily from foreign institutions, including those in the United States, and were overexposed to the domestic construction sector which experienced a sharp downturn immediately after the crisis started. But these Central Asian countries seemed to be better insulated than the CEE countries. For instance, windfall oil revenues had allowed Kazakhstan to build up estimated foreign exchange reserves of $16.8 billion in 2008, and in October 2008 the government had announced it was going to spend $5 billion to recapitalize struggling banks.

During the financial crisis, some sectors were more impacted than others. The uncertainty during the crisis caused consumers and businesses to postpone discretionary purchases, of which consumer durables and investment goods are the most important. In addition, these types of products are much more likely to be bought on credit than consumption nondurables, and once capital markets froze, financing was no longer available. In some countries, especially those with housing bubbles, the construction sector was also severely impacted.

The resource rich CIS, which includes Russia, had surpluses of over 10 percent of GDP going into the crisis and although these fell slightly in 2009 due to the fall in commodity prices early in that year, the surpluses were expected to start growing again in the following year. However, one should realize that although the CIS economies had overall current account surpluses, their private financial sectors were heavily dependent on external capital inflows. Thus, the dependence of the region on foreign capital to finance their future development was one of the most significant medium-run consequences of the current global economic crisis.

Some banks have failed during the crisis. In Russia about 20 banks failed. The government provided bailouts to systemically or regionally important banks. Depositors were generally protected and have not lost their money as they did in some previous crises. However, there were some minor problems, such as in Ukraine, where there were restrictions on bank withdrawals for a time. In a few cases, however, foreign bond holders or bank syndicates have had to take a haircut.

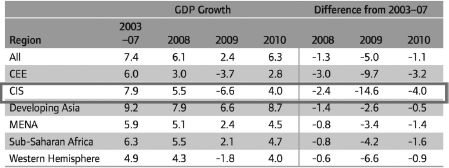

One simple way to gauge the effect of the crisis on CIS economies is to compare GDP growth over the period 2003 through 2007 with growth in 2008, 2009, and 2010, as outlined in Table 4.1. This suggests a shortfall of 1.3 percent in 2008, 5 percent in 2009, and 1.1 percent in 2010—or a cumulative loss of around 7.5 percent by 2010. The CIS region experienced a drop from 7.9 percent in 2003 to -6.6 percent in 2009, a total drop of 14.6 percent.

In the CIS, six of its economies, including Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Ukraine, had to resort to IMF assistance in the second half of 2008 and the beginning of 2009 to secure their international liquidity and avoid both sovereign default and an uncontrolled run on their currencies. Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, two of the least developed countries in the region, were better insulated due to their weaker international financial and trade links, but still were more affected than initially thought.

Table 4.1 GDP growth in emerging and developing economies (percent)

Source: IMF (2010).

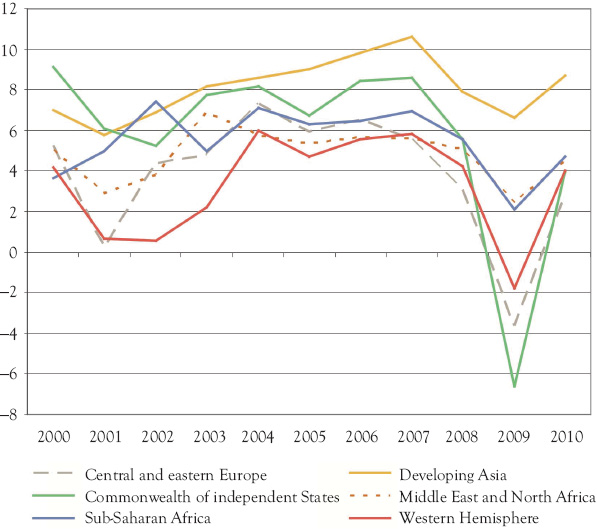

Figure 4.1 Real GDP growth in emerging and developing economies (percent)

Source: IMF.

As depicted on Figure 4.1, the real GDP of countries in the CIS, central and eastern Europe (CEE) and the Western Hemisphere contracted in 2009, while in developing Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) real GDP growth in 2009 was well below its average rate in the years leading up to the crisis.

Challenges and Implications

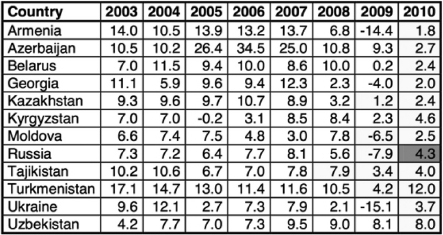

When it became clear that the crisis hit most emerging markets heavily, especially former communist economies in CEE and CIS, the previously optimistic forecasts gave way to alarming expectations and comments like that of the World Bank President Robert Zoellick’s on February 27, 2009.1 Even greater differences were observed within the CIS, as depicted in Table 4.2, where Ukraine contracted by 15.1 percent, Armenia by 14.4 percent, Russia by 7.9 percent, and Moldova by 6.5 percent. On the other hand, all 5 Central Asian countries, Azerbaijan, and Belarus continued growing, in some cases, Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan, at a pretty high rate. The CIS economies were the most impacted, dropping below -6 percent, but were also the ones to most aggressively recover, back to par with all other economic groups, except to developing Asia. Fortunately, these fears proved to be a bit exaggerated.

Clearly, all regions were badly affected. Countries in the CIS, as well as emerging economies in Asia, central and eastern Europe suffered the biggest falls in exports in 2009, both in absolute terms and relative to expectations, but even sub-Saharan Africa, which is less well integrated into the global economy, experienced a fall of 7 percent in exports in 2009.2

Table 4.2 Annual growth of real GDP, in percent, 2003–2010, CIS

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2010.

The effect of the crisis on private capital flows was another important factor as CIS countries were severely impacted, seeing some large inflows in 2007 replaced by large outflows in 2008 and 2009. The biggest increases and subsequent declines in capital flows were in portfolio and other financial flows. Direct investment flows were boosted in 2007 and 2008, probably due mainly to extraordinary increases in some commodity prices. They have subsequently fallen back, but look set to remain above their 2006 level.

The regions most badly hit by the freezing of credit markets and a consequent drying up of capital inflows were the CIS countries and central and eastern Europe. This led to what are best described as depressions in the region, where GDP contracted by between 14 and 18 percent in 2009, and to severe recessions in many other economies.

When one limits the analyzed cross-country panel to Europe and CIS, the correlations remain the same in terms of direction but not in terms of strength. Three of the aforementioned correlations—between the growth rate of real GDP in 2009 and GDP PPP per capita level in 2006, exports-to-GDP ratio in 2006 and domestic credit-to-GDP ratio in 2006 are negative but weaker for Europe and CIS than globally. The same concerns the positive correlation between the 2009 growth rate and the average growth rate in 2003 to 2007, which is weaker for Europe and the CIS. However, another positive correlation—between the 2009 growth rate and the average current account balance in 2005 to 2007—proved to be stronger for Europe and the CIS than globally.

Economic Prospects

There is little prospect of growth in the CIS region returning to its precrisis level any time soon and unemployment will remain high for many years. This is almost certain to lead to hysteresis effects, or what economists refer to as the risk of some cyclical effects, such as an increase in unemployment during a recession, become more permanent, or structural. For example, workers who are unemployed in the CIS region for any length of time may lose the skills they need to find employment or find it difficult to acquire new skills that may be needed to find a job. Thus, they may settle for employment that is less productive than what they are capable of, or they may drop out of the labor force altogether. The economy’s productive potential is, therefore, diminished.

Russia also experienced a sharp fall in capital in inflows in 2008 and 2009. These had been boosted ahead of the crisis by the high price of oil but fell away as the crisis developed. This had a very significant effect on the Russian economy, but also on the economies of many other countries in the CIS which had come to rely on exports to and remittance flows from Russia. We need to be careful, however, before attributing the problems of the CIS countries to the financial crisis alone. The exceptionally strong growth rates recorded there in the mid-2000s were, with the benefit of hindsight, unsustainable and only achievable because of some of the activities that ultimately caused the crisis.

Going beyond these general observations would require an analysis of structural data (e.g., the share of various sectors and industries) which are not available in terms of a cross-country comparative dataset. The only available figure of this kind, the average growth rate of the group of fuel exporters, indicates that they were more heavily hit in 2009 than other economies. Some anecdotal evidence may suggest that large shares of the construction, metallurgy, the automobile industries or the financial sector made the recent recession more severe.

On average, CIS countries have the chance to grow faster than the Euro area and the entire EU. This gives them the opportunity to continue the catching up process, although at a slower pace than during the boom preceding the recent crisis. However, the picture will be uneven within each regional group or subgroup as it was in 2009. And returning to the precrisis boom does not seem likely at least in the near future. In addition, the overall macroeconomic environment will be less comfortable, with higher debt-to-GDP ratios in most countries, and tighter credit conditions.

1 http://ft.com/cms/3cf2381c-c064-11dd-9559-000077b07658.html

2 It is not the focus of this chapter, not this book, for comprehensive analysis of the effects on individual countries. The Overseas Development Institute has examined the impact of the crisis on selected economies (ODI 2010).