Country Scanning of the CIS States

The following is a brief scanning of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries to help in the understanding of their challenges and competitive advantages in furthering their economies and global market integrations that are discussed in this book. The CIS is a regional organization which was created in December 1991 by the former Soviet Republics. In the adopted Declaration, the participants of the Commonwealth declared their interaction based on sovereign equality.

Originally, there were 12 member states that were part of the CIS, including Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, and Georgia. Both Ukraine and Georgia left the CIS in 2014 and 2009, respectively.

Armenia

Armenia is a unitary, multiparty, democratic nation-state with an ancient cultural heritage. The Satrapy of Armenia was established in the 6th century BC, after the fall of Urartu. In the 1st century BC the Kingdom of Armenia reached its height under Tigranes the Great. Armenia became the first country in the world to adopt Christianity as its official religion1 in between late 3rd century to early years of the 4th century, becoming the first Christian nation.2 Thus, previously predominant Zoroastrianism and paganism in Armenia gradually declined.

Figure A.1 Armenia is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia to the north, the de facto independent Nagorno-Karabakh Republic and Azerbaijan to the east, and Iran and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan to the south

Source: Magellan Geographix.

As depicted in Figure A.1, Armenia is a landlocked country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia, bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia to the north, the de facto independent Nagorno-Karabakh Republic and Azerbaijan to the east, and Iran and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan to the south. Armenia is the second most densely populated country of the former Soviet republics because of its small size.

Between the 16th century and first half of the 19th century, the traditional Armenian homeland composed of Eastern Armenia and Western Armenia came under rule of the rivaling Ottoman and successive Iranian Empires, passing between the two over the centuries. By the mid-19th century, Eastern Armenia had been conquered by Russia from Qajar Iran, while most of the western parts of the traditional Armenian homeland remained under Ottoman rule.

During World War I, the Armenians living in their ancestral lands in the Ottoman Empire were systematically exterminated in the Armenian Genocide in two phases: the wholesale killing of the able-bodied male population through massacre and subjection of army conscripts to forced labor, followed by the deportation of women, children, the elderly, and infirm on death marches leading to the Syrian desert. Driven forward by military escorts, the deportees were deprived of food and water and subjected to periodic robbery, rape, and massacre.3, 4 The Armenian Genocide is acknowledged to have been one of the first modern genocides.5 As per the research conducted by Arnold J. Toynbee, an estimated 600,000 Armenians died during deportation from 1915 to 1916. This figure, however, accounts for solely the first year of the Genocide and does not consider those who died or were killed after the report was compiled on the May 24, 1916.6 The International Association of Genocide Scholars places the death toll at “more than a million.”7 The total number of people killed has been most widely estimated at between 1 and 1.5 million.8

In 1918, during the Russian Revolution, all non-Russian countries were granted independence from the dissolved empire, leading to the establishment of the First Republic of Armenia. By 1920, the state was incorporated into the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, a founding member of the Soviet Union in 1922. In 1936, the Transcaucasian state was dissolved, leaving its constituent states, including the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, as full Union republics. The modern Republic of Armenia became independent in 1991 during the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Until its independence, Armenia’s economy was based largely on industries including chemicals, electronic products, machinery, processed food, synthetic rubber, and textiles. It has also been highly dependent on outside resources. Agriculture accounted for only 20 percent of net material product and 10 percent of employment before the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. Armenian mines produce copper, zinc, gold, and lead. The clear majority of energy is produced with imported fuel, including gas and nuclear fuel from Russia, to power its single nuclear power plant. The main domestic energy source is hydroelectric. Small amounts of coal, gas, and petroleum have not yet been developed.

Like other former states, Armenia’s economy suffers from the legacy of a centrally planned economy and the breakdown of former Soviet trading patterns. Soviet investment in and support of Armenian industry has virtually disappeared, so that few major enterprises are still able to function. In addition, the effects of the 1988 earthquake, which killed more than 25,000 people and left more than 500,000 people homeless, are still being felt. Although a ceasefire has held since 1994, the conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh has not been resolved. The consequent blockade along both the Azerbaijani and Turkish borders has devastated the economy, because of Armenia’s dependence on outside supplies of energy and most raw materials. Land routes through Azerbaijan and Turkey are still closed, while routes through Georgia and Iran are adequate and reliable.

In 1992 to 1993, the GDP had fallen nearly 60 percent from its 1989 level. The national currency, the dram, suffered hyperinflation for the first few years after its introduction in 1993. Nonetheless, Armenia has registered strong economic growth since 1995 and inflation has been negligible for the past several years. New sectors, such as precious stone processing, jewelry making and communication technology are flourishing. This steady economic progress has earned Armenia increasing support from international institutions. The government has made major strides toward joining the WTO, which it joined in 2003. The government also launched in 1994 an ambitious IMF-sponsored economic liberalization program that resulted in growth rates in 1995 to 2005.

Armenia also has managed to slash inflation, stabilize its currency, and privatize most small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Armenia’s unemployment rate, however, remains high, despite strong economic growth. Armenia is now a net energy exporter, although it does not have sufficient generating capacity to replace its nuclear power plant in Metsamor, which is under international pressure to close. The electricity distribution system was privatized in 2002.

The IMF, World Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), as well as other international financial institutions and foreign countries have been extending considerable grants and loans to the country targeted at reducing the budget deficit, stabilizing the local currency; developing private businesses; energy; the agriculture, food processing, transportation, and health and education sectors; and ongoing rehabilitation work in the earthquake zone. Hence, Armenia’s severe trade imbalance has been offset somewhat by international aid, remittances from Armenians working abroad, and foreign direct investment.

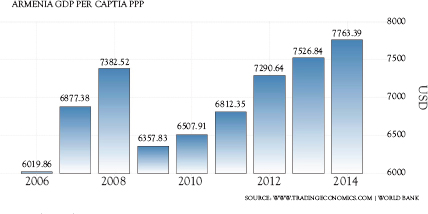

Per the World Bank, and depicted in Figure A.2, the GDP per capita in Armenia was last recorded at $7,763.39 in 2014, when adjusted by purchasing power parity (PPP). The GDP per Capita, in Armenia, when adjusted by PPP is equivalent to 44 percent of the world’s average. GDP per capita PPP in Armenia averaged $4,464.91 from 1990 until 2014, reaching an all-time high of $7,763.39 in 2014 and a record low of $1,841.72 in 1993.

Continued progress will depend on the ability of the government to strengthen its macroeconomic management, including increasing revenue collection, improving the investment climate, and accelerating privatization. A liberal foreign investment law was approved in June 1994, and a law on privatization was adopted in 1997, as well as a program on state property privatization.

Figure A.2 Armenia GDP per capita

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.com.

Located in the South Caucasus, Azerbaijan is a transcontinental country situated at the crossroads of The CIS and Western Asia. While often politically aligned with Europe, Azerbaijan is generally considered to be at least mostly in Southwest Asia geographically with its northern part bisected by the standard Asia-Europe divide, the Greater Caucasus. The UN and CIA classification of the country differs, with the UN placing Azerbaijan in Western Asia, while the CIA World Factbook places it mostly in Southwest Asia, and the Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary places them in both! We’ll let you take a pick! Nonetheless, the country, as depicted in Figure A.3, bordered by the Caspian Sea to the east, Russia to the north, Georgia to the northwest, Armenia to the west and Iran to the south. In addition, the exclave of Nakhchivan is bounded by Armenia to the north and east, Iran to the south and west, while having a short border with Turkey in the northwest.

The country proclaimed its independence in 1918 and became the first Muslim-majority democratic and secular republic and to have operas, theaters and modern universities.9,10 The Constitution of Azerbaijan does not declare an official religion, and all major political forces in the country are secularist, but most people and some opposition movements adhere to Shia Islam.11 Azerbaijan was incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1920 as the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, proclaiming its independence from the USSR in August 1991, before the official dissolution of the USSR.12 In September 1991, the disputed Armenian-majority Nagorno-Karabakh region reaffirmed its willingness to create a separate state as the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. The region, effectively independent since the beginning of the Nagorno-Karabakh War in 1991, is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan until a final solution to its status is found through negotiations facilitated by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).13

Figure A.3 Azerbaijan is bordered by the Caspian Sea to the east, Russia to the north, and Georgia to the northwest, and Armenia to the west and Iran to the south

Source: CDC.

Azerbaijan is a unitary semipresidential republic. The country is a member state of the Council of Europe, the OSCE and the NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP) program. It is one of the six independent Turkic-speaking states, being an active member of the Turkic Council and the TÜRKSOY community. The country has diplomatic relations with 158 countries and holds membership in 38 international organizations. It is one of the founding members of the CIS14 and Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Also, a member of the UN since 1992, Azerbaijan was elected to membership in the newly established Human Rights Council by the United Nations General Assembly in May 2006. The country is also a member state of the Non-Aligned Movement, holds observer status in World Trade Organization and is a correspondent at the International Telecommunication Union.

Economically, Azerbaijan has completed its post-Soviet transition into a major oil-based economy from one where the state played the major role. Economic growth has been spurred by the exploration and development of oil and gas reserves, high levels of public expenditure, and substantial reforms to support a market-based economy. Despite robust growth, the economy of Azerbaijan remains largely dependent upon the extraction and production of fossil fuels. Today, however, the country is an oil-rich economy whose gross national income per capita has increased approximately tenfold since 2001.

As depicted in Figure A.4, Azerbaijan’s GDP per capita in Azerbaijan was last recorded at $16,710.30 in 2014, when adjusted by PPP. The country’s GDP per capita when adjusted by PPP is equivalent to 94 percent of the world’s average. GDP per capita PPP in Azerbaijan averaged $8,777.13 from 1990 until 2014, reaching an all-time high of $16,710.30 in 2014 and a record low of $3,319.77 in 1995.15 Such rates cannot be sustained, but despite reaching 26.4 percent in 2005 (second highest GDP growth in the world in 2005 only to Equatorial Guinea), and 2006 over 34.6 percent (world highest), in 2008 dropped to 10.8 percent, and dropped further to 9.3 percent in 2009.16 The national currency, the Azerbaijani manat, was stable in 2000, depreciating 3.8 percent against the dollar. The budget deficit equaled 1.3 percent of GDP in 2000.

Figure A.4 Azerbaijan GDP growth

Source: World Bank, trendingeconomics.com.

Progress on economic reform has generally lagged macroeconomic stabilization. The government has undertaken regulatory reforms in some areas, including substantial opening of trade policy, but inefficient public administration in which commercial and regulatory interests are comingled limit the impact of these reforms. The government has largely completed privatization of agricultural lands and SMEs. In August 2000, the government launched a second-stage privatization program, in which many large state enterprises will be privatized. Since 2001, the economic activity in the country is regulated by the Ministry of Economic Development of Azerbaijan Republic.

The manat tumbled by more than 30 percent following Azerbaijan’s switch from a currency peg to a free-floating exchange rate. The move, which represented the second drastic devaluation of the currency in 2015, is aimed at protecting the country’s dwindling foreign exchange reserves, which have come under pressure from falling oil prices and the economic crisis in Russia, and to restore export competitiveness. Oil and gas account for more than 90 percent of Azerbaijan’s exports and 70 percent of government revenues. While the devaluation seemed inevitable against the backdrop of tumbling foreign reserves, it will likely have a negative impact on salaries, pensions and savings in local currency, fuel inflation and increase concerns over the Azerbaijani banking sector, which has a large share of bank deposits denominated in foreign currency.

In 2015, Azerbaijan’s economy rebounded, however, with robust growth of 5.7 percent in the first half of the year, up from 2.1 percent in the same period in 2014. Boosted mainly by government capital expenditure, the economy outside of the large petroleum sector was the major driver of growth. The public investment program remains a key source of economic expansion and employment, but budget revenues are under pressure from lower oil prices.

Official foreign currency reserves fell by more than 30 percent in January to August 2015 because the central bank intervened to maintain the new exchange rate after the February 2015 devaluation of the Azerbaijan manat. Oil prices, key to local currency stability, have fallen dramatically over the past year, from $103.08 per barrel of Azeri light crude in August 2014 to $46.23 a year later.

To limit inflation, the central bank has reduced local currency liquidity. With tepid domestic demand, largely offsetting price pressures from the devaluation, year-on-year inflation rose to only 3.5 percent in the first half of 2015, which was nevertheless up from 1.6 percent for the same period in 2014. The devaluation will continue to put inflationary pressure on imports other than food.

Azerbaijan faces a multifaceted crisis in 2016 to 2017. Low oil prices led to a major currency devaluation in 2015, which will depress consumption and investment and push up inflation. Pressure on the currency remains high, and the authorities imposed currency controls in mid-January 2016. The banking sector will suffer major losses this year, and depend heavily on state support. Falling incomes and rising unemployment will lead to protests in some areas and a rise in political uncertainty.

Belarus

Belarus, as depicted in Figure A.5, is a landlocked country in the CIS bordered by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk, and count with over 40 percent of its 207,600 square kilometers (80,200 sq. mi.) is forested. Its strongest economic sectors are service industries and manufacturing.

Until the 20th century, different states at various times controlled the lands of today’s Belarus. In the aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution, Belarus declared independence as the Belarusian People’s Republic, succeeded by the Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia, which became a founding constituent republic of the Soviet Union in 1922, then renamed as the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. The country lost almost half of its territory to Poland after the Polish-Soviet war of 1919 to 1921, with most of the borders of Belarus adopting their modern shape in 1939 when some lands of the Second Polish Republic were reintegrated into it after the Soviet invasion of Poland and were finalized after World War II.17,18

Figure A.5 Belarus is a landlocked country in the CIS bordered by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest

Source: globalsecurity.org.

During World War II, military operations devastated Belarus, which lost about a third of its population and more than half of its economic resources.19 The republic was redeveloped in the postwar years. In 1945 Belarus became a founding member of the UN, along with the Soviet Union and the Ukrainian SSR. Later, during the dissolution of the Soviet Union the parliament of the republic declared the sovereignty of Belarus, in July 1990, becoming independence on August 25, 1991.

As per data from the U.S. government,20 most of the Belarusian economy remains state controlled and has been described as “Soviet-style.” In 2006, foreign companies employed state-controlled companies employed 51.2 percent of Belarusians, 47.4 percent were employed by private companies, of which 5.7 percent were partially foreign owned. Important agricultural products include potatoes and cattle byproducts, including meat.21

After the fall of the Soviet Union, all former Soviet republics faced a deep economic crisis. Belarus has however chosen its own way of overcoming this crisis. After the 1994 election of Alexander Lukashenko as the country’s first president, he launched the country on a path of “market socialism” as opposed to what Lukashenko considered “wild capitalism” chosen by Russia at that time. In keeping with this policy, administrative controls over prices and currency exchange rates were then introduced. Also, the state’s right to intervene in the management of private enterprise was expanded, but on March 4, 2008, the president issues a decree abolishing the golden share rule in a clear movement to improve its international rating regarding the foreign investment.

Historically, textiles and wood processing had constituted a large part of the industrial activity in the country. Belarus’s main exports included heavy machinery, agricultural products, and energy products. At the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Belarus was one of the world’s most industrially developed states by percentage of GDP as well as the richest CIS member state. Economically, Belarus involved itself in the CIS, Eurasian Economic Community, and Union with Russia.

The currency, the Belarusian ruble (BYR), was introduced in May 1992, replacing the Soviet ruble. The first coins of the Republic of Belarus were issued on December 27, 1996. The ruble was reintroduced with new values in 2000 and has been in use ever since. As part of the Union of Russia and Belarus, both states have discussed using a single currency along the same lines as the Euro. This led to a proposal that the Belarusian ruble be discontinued in favor of the Russian ruble (RUB), starting as early as January 1, 2008. The National Bank of Belarus abandoned pegging the Belarusian ruble to the Russian ruble in August 2007. A new currency, the new Belarusian ruble (BYN) will be introduced in July 2016, replacing the Belarusian ruble in a rate of 1:10,000 (10,000 old rubles = 1 new ruble). This redenomination can be considered an effort to fight the high inflation rate.

Regarding GDP growth, back in the 1990s-industrial production had plunged due to decreases in imports, investment, and demand for Belarusian products from its trading partners, which impacted GDP growth. But as depicted in Figure A.6, GDP began rising again in 1996, when Belarus became the fastest-recovering former Soviet republic in the terms of its economy. The GDP per capita in Belarus was last recorded at $17,348.77 in 2014, when adjusted by PPP, which is equivalent to 98 percent of the world’s average.22

In 2006, Belarus’s largest trading partner was Russia, which accounted for nearly half of total trade, with the EU was the next largest trading partner, with nearly a third of foreign trade. In 2005, about a quarter of the population was employed by industrial factories but employment was, and continue to be, high in agriculture, manufacturing sales, trading goods, and education. Because of its failure to protect labor rights for a labor force of more than 4 million people, among whom women hold slightly more jobs than men, Belarus lost its EU Generalized System of Preferences status in June 2007, which raised tariff rates to their prior most favored nation levels.23

Figure A.6 Belarus GDP per capital in PPP terms 1990–2015

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.

Weak external demand from the key trading partners of Russia and Ukraine has depressed Belarus’ output in early 2015. In addition, despite tightening of monetary policy, inflation has been high due to the impact from exchange rate depreciation. Although net exports slightly improved, foreign exchange reserves declined due to large external debt repayments. Despite the weaker economy, the government has managed to keep fiscal policy prudent. Stability-oriented macroeconomic tightening has occurred in response to a deteriorating external environment. The economy was expected to enter a recession during 2015, which was likely to endure in 2016. The current economic challenges and domestic structural constraints reinforce the need for a comprehensive economic transformation.

Georgia

Georgia is a country in Eurasia, located on the crossroads of the CIS and West Asia. As depicted in Figure A.7, the country is nestled between the Greater Caucasus and Lesser Caucasus mountain ranges. It is bordered to the west by the Black Sea, to the north and northeast by Russia, to the south by Turkey and Armenia, and to the southeast by Azerbaijan. The capital and largest city is Tbilisi. Georgia covers a territory of 69,700 square kilometers (26,911 sq. mi.), and its 2015 population is about 3.75 million. Georgia is a unitary, semipresidential republic, with the government elected through a representative democracy.

During classical antiquity, several independent kingdoms became established in what is now Georgia, including the kingdoms of Colchis and Iberia, which adopted Christianity as their state religion in the early 4th century, leading to the decline and elimination of previously dominant paganism, Zoroastrianism, and Mithraism. Thereafter and throughout the early modern period Georgia became fractured and fell into decline due to the onslaught of various hostile empires, including the Mongols, the Ottoman Empire, and successive dynasties of Iran. After a brief period of independence following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the first Georgian Republic was occupied by Soviet Russia in 1921, and absorbed into the Soviet Union as the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1922. After restoring its independence in 1991, post-communist Georgia suffered from a civil unrest and economic crisis for most of the 1990s. After a peaceful change of power in the Rose Revolution of 2003, Georgia pursued a strongly pro-Western foreign policy, introducing a series of political and economic reforms.

Figure A.7 Georgia is bordered by the Black Sea on the west, to the north and northeast by Russia, to the south by Turkey and Armenia, and to the southeast by Azerbaijan

Source: RandMcnally.

Georgia is a member of the Council of Europe and the GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development. It contains two de facto independent regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which gained limited international recognition after the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. Georgia and a major part of the international community consider the regions to be part of Georgia’s sovereign territory under Russian military occupation.

In February 1921, the Red Army attacked Georgia defeating the Georgian army and prompting the Social-Democratic government to flee the country. By the end of February 1921, the Red Army entered Tbilisi and installed a communist government loyal to Moscow, led by a Georgian Bolshevik named Filipp Makharadze. There remained, however, significant opposition to the Bolsheviks, which culminated in the August 1924 Uprising. Soviet rule was firmly established only after this uprising was suppressed.24 Georgia was then incorporated into the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (TSFSR), which united Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Later, in 1936, the TSFSR was disaggregated into its component elements and Georgia became the Georgian SSR.

Joseph Stalin, an ethnic Georgian born Ioseb Besarionis Dze Jugashvili in Gori, was prominent among the Bolsheviks. Stalin was to rise to the highest position, leading the Soviet Union from April 3, 1922 until his death on March 5, 1953. Few years later, for most of the World War II period, during 1941 to 1945, almost 700,000 Georgians fought in the Red Army against Nazi Germany, even though a few fought on the German side. About 350,000 Georgians died in the battlefields of the Eastern Front.

Georgia’s main economic activities include cultivation of agricultural products such as grapes, citrus fruits, and hazelnuts, as well as mining of manganese, copper, and gold. It also produces alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages, metals, machinery, and chemicals in small-scale industries. The country imports nearly all its needed supplies of natural gas and oil products. It has sizeable hydropower capacity that now provides most of its energy needs. Georgia has overcome the chronic energy shortages and gas supply interruptions of the past by renovating hydropower plants and by increasingly relying on natural gas imports from Azerbaijan instead of from Russia.

Despite the severe damage the economy of Georgia suffered due to civil strife in the 1990s, the country has recovered significantly by 2000, with the help of the IMF and World Bank. As depicted in Figure A.8, robust GDP growth has been achieved since then. GDP growth, spurred by gains in the industrial and service sectors, remaining in the 9 to 12 percent range in 2005 to 07, but during 2006 and in 2008, the World Bank named Georgia the top reformer in the world.25

Figure A.8 Georgia GDP growth in PPP, period 2006–2014

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.

Favorable domestic conditions and strong external demand supported economic growth in the first half of this year, demonstrating that regional economic tensions have not yet adversely affected Georgia. The large Russian market, which opened for Georgian products in July 2015, helped increase exports, particularly of wine. Greater consumer and business confidence gave a boost to manufacturing and trade. In addition, the construction sector benefited from renewed public infrastructure projects and resumption in business related investments. The agricultural sector grew at a relatively modest pace compared with industry and services.

GDP growth did slow in the first quarter of 2015 to 3.2 percent from 4.8 percent for the whole of 2014. Preliminary data show a further slowdown to 2.6 percent in the first half of 2015. The slowdown largely reflects declines of 5.2 percent in manufacturing and 2.5 percent in trade, and it came despite strong growth of 22.9 percent in mining and 17.2 percent in construction. After expanding by 12.2 percent in the first quarter, bank credit fell by 1.5 percent in the second in line with slower growth.

Annual average inflation in August 2015 amounted to 3.2 percent as large increases for tobacco and alcoholic beverages and furnishings, household equipment, and maintenance offset smaller declines for transport and clothing and footwear. Continuing moderate inflation, despite depreciation of the Georgia lari by nearly 33 percent since November 2014, reflects weakening domestic demand and reduced profit margins for firms, along with lower prices for imported food and energy. Inflationary expectations have recently increased, however, with the depletion of inventories accumulated at cheaper prices, rising production costs, and extensive dollarization in the economy.

Though export data for the first 6 months of 2015 suggested a further cut in exports of nearly 24 percent, reflecting a drop-in vehicle exports by nearly two-thirds, lower oil prices helped cut imports by about 9 percent. In addition, sharp declines in remittances, from the Russian Federation and Greece by 41 and 19 percent, respectively, caused total remittances to fall by almost 23 percent in the first half of 2015.

Despite planned fiscal consolidation, capital spending is expected to contribute to growth in the second half of 2015 and in 2016. However, net exports will remain a drag on growth, as recession in the Russian Federation and Ukraine weakens the external outlook. Inflation is expected to accelerate to about 6 percent by the end of 2016. With tighter monetary policy, according to the Asian Development Bank26 outlook for Georgia in 2015 and 2016, the current account deficit may reach 14.1 percent of GDP in the first quarter of 2016 as the trade deficit widened and the regional economic slowdown trimmed remittances. The deficit was funded largely through foreign direct investment inflows and official development assistance.

Georgia has a developed, stable, and reliable energy sector but efforts are required to improve the efficiency in domestic energy use. The most promising source of additional energy generation is hydropower and the Government is focused on securing private investments for construction of new hydropower stations. Currently, only 12 percent of Georgia’s hydropower potential is being utilized.

One of the potential drivers of economic growth in cities and regions is tourism, which recently saw rapid growth in Georgia and has become an important source of job creation. The number of visitors increased from 560,000 in 2005 to 5 million in 2015, with 6.3 million expected in 2015. An integrated and demand-driven approach to regional development has been designed with the support of the Bank and is currently seen as critical in spurring growth and job creation in historic cities and cultural villages.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, the world’s largest landlocked country by land area, is a country in Central Asia, with a minor part west of the Ural River and thus in Europe. As depicted in Figure A.9, the country borders Russia on the north, China on the east, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan on the south, and the Caspian Sea on the west.

The terrain of Kazakhstan includes flatlands, steppe, taiga, rock canyons, hills, deltas, snow-capped mountains, and deserts. With an estimated 18 million people, as of 2014, Kazakhstan is the 61st most populous country in the world. Given its large land area, its population density is among the lowest, at less than 6 people per square kilometer (15 people per sq. mi.). The capital is Astana, where it was moved in 1997 from Almaty. Nomadic tribes have historically inhabited the territory of Kazakhstan. This changed in the 13th century, when Genghis Khan occupied the country as part of the Mongolian Empire.

Figure A.9 Kazakhstan borders Russia on the north, China on the east, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan on the south, and the Caspian Sea on the west

Source: Eurasianet.org.

Following internal struggles among the conquerors, power eventually reverted to the nomads. By the 16th century, the Kazakh emerged as a distinct group, divided into three jüz (ancestor branches occupying specific territories). The Russians began advancing into the Kazakh steppe in the 18th century, and by the mid-19th century, they nominally ruled all of Kazakhstan as part of the Russian Empire. Following the 1917 Russian Revolution and subsequent civil war, the territory of Kazakhstan was reorganized several times. In 1936 it was made the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, considered an integral part of the Soviet Union.

Kazakhstan was the last of the Soviet republics to declare independence following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Kazakhstan has worked to develop its economy, especially its dominant hydrocarbon industry.27 Human Rights Watch says that “Kazakhstan heavily restricts freedom of assembly, speech, and religion,28” and other human rights organizations regularly describe Kazakhstan’s human rights situation as poor.

The country is populated by 131 ethnicities, including Kazakhs (who make up 63 percent of the population), Russians, Uzbeks, Ukrainians, Germans, Tatars, and Uyghurs. Islam is the religion of about 70 percent of the population, with Christianity practiced by 26 percent. Kazakhstan officially allows freedom of religion, but religious leaders who oppose the government are suppressed. The Kazakh language is the state language, and Russian has equal official status for all levels of administrative and institutional purposes, reflecting the long history of Russian dominance in the region.

Kazakhstan is an upper-middle-income country with per capita GDP adjusted for PPP, as depicted in Figure A.10, of nearly $22,469 thousand in 2015. Its per capita GDP grew in 2014 although real GDP dropped due to internal capacity constraints in the oil industry, less favorable terms of trade, and an economic slowdown in Russia. The contribution of net exports to GDP growth improved materially followed by a sharp devaluation of the Kazakhstan tenge in February 2014, leading to a strong drop in imports of goods that became costlier. Because of the devaluation, domestic inflation, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI), increased from 4.8 percent year-on-year in December 2015 to 6.9 percent in August 2014, due to higher imported input prices.

Figure A.10 Kazakhstan GDP per capita PPP 2006–2014

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.

Income growth in the country had a positive impact on poverty indicators, with prosperity shared broadly. The share of the Kazakhstan population living in poverty went down from 47 percent in 2001 to about 3 percent in 2015, as measured by the national poverty line. Similarly, at the international poverty line, as measured by the PPP-corrected $2.50 per capita per day, poverty in Kazakhstan fell from 41 percent in 2001 to 4 percent in 2009.

However, against a benchmark of a higher poverty line at the PPP-corrected $5 per capita per day (which is more appropriate for countries with a higher level of income per capita), some 42 percent of Kazakhstan’s population were still living in poverty in 2009, though down from 79 percent in 2001. Kazakhstan’s performance in the World Bank’s indicator of shared prosperity also shows progress, with growth rate of consumption per capita of the bottom 40 percent of households of about 6 percent, while the average consumption growth for all households was about 5 percent during 2006 to 2010.

Trade policy will remain a central instrument to help the country integrate into the global economy, but Kazakhstan will face a complex trade policy environment in the medium term. The economy is adjusting to the Eurasia Customs Union which it joined in 2010 and is pursuing an accelerated schedule of further integration into the Common Economic Space by 2015. Kazakhstan is also expected to join the World Trade Organization soon while its trade strategy lists several free trade agreements to be negotiated.

Education is a high priority for Kazakhstan, and in 2011, Kazakhstan ranked first on UNESCO’s “Education for All Development Index” by achieving near-universal levels of primary education, adult literacy, and gender parity. These results have reflected Kazakhstan’s efforts of expanding preschool access and free, compulsory secondary education. For the next 10 years, Kazakhstan is embarking on further major reforms across all education levels.

Kazakhstan faces challenges in restructuring its health care system. The country’s health outcomes lag its rapidly increasing income. The major causes of adult mortality are noncommunicable diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other tobacco and alcohol-related diseases and injuries. The new State Health Care Development Program recognizes health as one of the country’s major priorities and a prerequisite for sustainable socioeconomic development.

Looking forward, despite the short-term vulnerabilities accentuated by the uncertain regional economic outlook, Kazakhstan’s medium-term prospects look promising. In the medium term, the economy will continue to grow on the back of the expanding oil sector, while growth of the nonoil economy will be lower due to lower domestic demand. In the longer run, Kazakhstan’s development objective of joining the rank of the top 30 most developed countries by 2050 will depend on its ability to sustain balanced and inclusive growth. Enhancing medium- to long-term development prospects depends on Kazakhstan’s success in diversifying its endowments, namely, creating highly skilled human capital, improving the quality of physical capital, and more importantly, strengthening institutional capital—all the necessary ingredients for the development and expansion of the private sector in the country.

Kyrgyzstan’s history spans over 2,000 years, encompassing a variety of cultures and empires. Although geographically isolated by its highly mountainous terrain, which has helped preserve its ancient culture, Kyrgyzstan has historically been at the crossroads of several great civilizations, namely as part of the Silk Road and other commercial and cultural routes. Though long inhabited by a succession of independent tribes and clans, Kyrgyzstan has periodically come under foreign domination and attained sovereignty as a nation state only after the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The country, officially known as Kyrgyz Republic, is a country located in Central Asia. As depicted in Figure A.11, the country is landlocked and mountainous, bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, and Tajikistan to the southwest and China to the east. Its capital and largest city is Bishkek.

Since independence, Kyrgyzstan has officially been a unitary parliamentary republic, although it continues to endure ethnic conflicts, revolts, economic troubles, transitional governments, and political party conflicts.29 Kyrgyzstan is a member of the CIS, the Eurasian Economic Union, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, the Turkic Council, the TÜRKSOY community, and the UN.

Figure A.11 Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the southwest and China to the east

Ethnic Kyrgyz make up much of the country’s 5.7 million people, followed by significant minorities of Uzbeks and Russians. The official language, Kyrgyz, is closely related to the other Turkic languages, although Russian remains widely spoken, a legacy of a century-long policy of Russification. Most of the population, about 64 percent, is nondenominational Muslims. In addition to its Turkic origins, Kyrgyz culture bears elements of Persian, Mongolian, and Russian influence.

After independence in 1992, the Kyrgyz Republic’s economy and public services were hit hard by the breakup of the Soviet economic zone and the end of subsidies from Moscow. Thanks to the adoption of market-based economic reforms in the 1990s, the economy has nearly recovered to its pre-independence level of output, but infrastructure and social services have suffered from low investment. With a per capita PPP GDP of $2,920.60 in 2011, as depicted in Figure A.12, the Kyrgyz Republic remains a low-income country. Moreover, the global economic crisis, the political unrest of April and June 2010 and food price increases in 2011 and 2012 have reversed earlier gains in poverty reduction with GDP dropping to $2,869.82. The absolute poverty rate increased from 33.7 percent in 2010 to 36.8 percent in 2011.

Figure A.12 Kyrgyzstan per capita GDP 2006–2014

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.

A series of reform-oriented government policies since the political crises of 2010, have sought to restore economic and social stability, and to address shortcomings in public governance and the investment climate. Following strong growth in 2015, the Kyrgyz economy was hit by a significant decline in gold production due to geological movements at the Kumtor gold mine. Real GDP in the first half of 2012 contracted by 5.6 percent as gold production at Kumtor fell by 60 percent. Excluding Kumtor, real output grew moderately at 3.9 percent with growth across all sectors.

Weak economic governance and a high level of perceived corruption remain key obstacles to development in the Kyrgyz Republic, and were considered causes of the political unrest of 2010. The government’s Medium Term Development Program, adopted in 2011, stated improving governance and fighting corruption to be its top priority.

The agricultural sector, which accounts for about a quarter of the country’s GDP and about one third of employment, expanded rapidly between 1996 and 2002. The Government successfully completed a land reform, created a rural bank and agribusiness or rural advisory services, and established water-user associations and pasture committees. The energy sector is one of the largest in the Kyrgyz economy, accounting for around 3.9 percent of GDP and 16 percent of industrial production. The bulk of the country’s current generating capacity is hydropower. The key challenges faced by the sector are high commercial losses and low tariffs, leading to inadequate funding for maintenance and investment, winter energy shortages, and governance issues. All these led to significant deterioration of energy assets and poor sector performance. Mining constitutes about 26 percent of tax revenues, about 10 percent of GDP, and 50 percent of export earnings. The country has been reviewing mining legislation and mineral licensing procedures. To address governance issues in mining, the Kyrgyz Government started implementing the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative in 2004.

The road network connects remote communities and links the Kyrgyz Republic to neighboring countries. Rehabilitating strategic road corridors is on the Government’s priority list, given their importance in providing access to international markets and basic public services. However, basic preventative maintenance is seriously underfunded.

Improving education, health care and social protection is another top priority for the Kyrgyz Republic. The Government is currently implementing medium term reforms in these sectors.

Moldova

Moldova, as depicted in Figure A.13, is a landlocked country in the CIS, bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The capital city is Chișinău. Moldova is a parliamentary republic with a president as head of state and a prime minister as head of government. It is a member state of the UN, the Council of Europe, the WTO, the OSCE, the GUUAM (Georgia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Moldova), the CIS and the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) and aspires to join the EU.

Figure A.13 Moldova is a landlocked country in The CIS, bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south

Source: Magellan Geographix.

Moldova declared independence on August 27, 1991 as part of the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The current Constitution of Moldova was adopted in 1994. A strip of Moldovan territory on the east bank of the river Dniester has been under the de facto control of the breakaway government of Transnistria since 1990, which includes a large proportion of predominantly russophone East Slavs of Ukrainian (28 percent) and Russian (26 percent) descent (altogether 54 percent as of 1989), while Moldovans (40 percent) have been the largest ethnic group, and where the headquarters and many units of the Soviet 14th Guards Army were stationed, an independent Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed on August 16, 1990, with its capital in Tiraspol.

The motives behind this move were fear of the rise of nationalism in Moldova and the country’s expected reunification with Romania upon secession from the USSR. In the winter of 1991 to 1992 clashes occurred between Transnistrian forces, supported by elements of the 14th Army, and the Moldovan police. Between March 2 and July 26, 1992, the conflict escalated into a military engagement.

After the breakup from the USSR in 1991, energy shortages, political uncertainty, trade obstacles and weak administrative capacity contributed to the decline of economy. In January 1992, Moldova introduced a market economy, liberalizing prices, which resulted in rapid inflation. As a part of an ambitious economic liberalization effort, Moldova introduced a convertible currency, liberalized all prices, stopped issuing preferential credits to state enterprises, backed steady land privatization, removed export controls, and liberalized interest rates. The government entered agreements with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to promote growth. The economy reversed from decline in late 1990s.

From 1992 to 2001, the country suffered a serious economic crisis, leaving most of the population below the poverty line. In 1993, a national currency, the Moldovan leu, was introduced to replace the temporary coupon. The economy of Moldova began to change in 2001, and until 2008 the country saw a steady annual growth of between 5 and 10 percent.

The early 2000s also saw a considerable growth of emigration of Moldovans looking for work in Russia, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, and other countries. Thus, remittances from Moldovans abroad account for almost 38 percent of Moldova’s GDP, the second-highest percentage in the world, after Tajikistan. Due to a decrease in industrial and agricultural output following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the service sector has grown to dominate Moldova’s economy and currently composes over 60 percent of the nation’s GDP. However, Moldova remains the poorest country in Europe.

Moldova’s economic performance over the last few years, as depicted in Figure A.14, has been relatively strong, aided by improved fiscal, monetary and exchange rate policy. Moldova experienced the highest cumulative per capita PPP GDP growth, relative to the precrisis year of 2007, in the region. However, growth has been volatile because of climatic and global economic conditions. The GDP per capita in Moldova was last recorded at $4,753.55 in 2014, when adjusted by PPP. The GDP per capita, in the country, when adjusted by PPP is equivalent to 27 percent of the world’s average. GDP per capita PPP in Moldova averaged $3,476.80 from 1990 until 2014, reaching an all-time high of $6,416.46 in 1990 and a record low of $2,267.88 in 1999.

Figure A.14 Moldova’s per capita PPP GDP 2006–2015

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.com.

However, the economy decreased 3.7 percent in the third quarter of 2015. Due to a bad harvest, agriculture decreased 17.4 percent and on the expenditure, side the internal demand was weak due to low remittances. Nonetheless, good economic performance in the first half of the year, maintained Moldova’s GDP growth positive, increasing 0.5 percent, y/y, in January to September 2015.

The existing macroeconomic framework is considered broadly adequate, even though macroeconomic risks associated with the financial sector, vulnerabilities to external and climatic shocks, institutional weaknesses and related slippages in the implementation of macroeconomic and structural reforms will continue to be substantial over the medium term. European integration anchors the Government’s policy reform agenda, but political tensions and weak governance pose risks to reforms.

Moldova’s recent economic performance reduced poverty and promoted shared prosperity. The national poverty and extreme poverty rates, using national poverty definitions, fell from 30.2 and 4.5 percent in 2006 to 16.6 and 0.6 percent respectively in 2012, making Moldova one of the world’s top performers in terms of poverty reduction. Similarly, consumption growth among the bottom 40 percent of the population outpaced average consumption growth.

Despite a sharp decline in poverty, however, Moldova remains one of the poorest countries in Europe. The most vulnerable groups at risk of poverty in Moldova remain those with low education levels, households with three or more children, those in rural areas, families relying on self-employment, the elderly, and Roma. Additionally, the reduction in remittances could negatively impact consumption and poverty. Moldova performs well in some areas of gender equality, yet disparities persist in education, health, economic opportunity, agency, and violence against women. Human trafficking is a serious problem; Moldova is a source, and to a lesser extent a transit and destination country, for both sex trafficking and forced labor.

Considering the fragile economic and political external environment the pace of reforms must be accelerated. Key challenges include fighting corruption, improving the investment climate, removing obstacles for exporters, channeling remittances into productive investments, and developing a sound financial sector. Moldova needs to improve the efficiency and equity of its public spending, through better management of public capital investments, which are crucial for higher growth. Administrative and judicial reforms remain a challenge for improving public sector governance, which is a precondition for European integration and economic modernization.

Russia

Russia, a federal semipresidential republic, is a country in northern Eurasia, the largest country in the world, covering more than one-eighth of the Earth’s inhabited land area. Russia is the world’s ninth most populous country with over 144 million people at the end of 2015. Extending across the entirety of northern Asia and much of The CIS, Russia spans over 11 time zones and incorporates a wide range of environments and landforms. As depicted in Figure A.15, from northwest to southeast, Russia is boarded by Norway, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine on the west, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, China, Mongolia, and North Korea to the south, and the North Pacific Ocean to the east. It shares maritime borders with Japan by the Sea of Okhotsk and the U.S. state of Alaska across the Bering Strait.

Figure A.15 Russia is boarded by Norway, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine to the west; Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, China, Mongolia, and North Korea to the south; and the North Pacific Ocean to the east; it shares maritime borders with Japan by the Sea of Okhotsk and the U.S. state of Alaska across the Bering Strait

Source: Russialist.org.

The nation’s history began with that of the East Slavs, who emerged as a recognizable group in Europe between the 3rd and 8th centuries AD. Founded and ruled by a Varangian warrior elite and their descendants, the medieval state of Rus arose in the 9th century. In 988 it adopted Orthodox Christianity from the Byzantine Empire, beginning the synthesis of Byzantine and Slavic cultures that defined Russian culture for the next millennium. Rus’ ultimately disintegrated into several smaller states; most of the Rus’ lands were overrun by the Mongol invasion and became tributaries of the nomadic Golden Horde in the 13th century.

The Grand Duchy of Moscow gradually reunified the surrounding Russian principalities, achieved independence from the Golden Horde, and came to dominate the cultural and political legacy of Kievan Rus.’ By the 18th century, the nation had greatly expanded through conquest, annexation, and exploration to become the Russian Empire, which was the third largest empire in history, stretching from Poland in Europe to Alaska in North America.30

Following the Russian Revolution, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic became the largest and leading constituent of the Soviet Union, the world’s first constitutionally socialist state and a recognized world superpower, and a rival to the United States,31 which played a decisive role in the Allied victory in World War II. The Soviet era saw some of the most significant technological achievements of the 20th century, including the world’s first human-made satellite, and the first man in space. By the end of 1990, the Soviet Union had the world’s second largest economy, largest standing military in the world and the largest stockpile of weapons of mass destruction.

Following the partition of the Soviet Union in 1991, 14 Independent republic nations emerged from the USSR, including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan. As the largest, most populous, and most economically developed republic, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (SFSR) reconstituted itself as the Russian Federation and is recognized as the continuing legal personality of the Soviet Union.

The Russian economy ranks as the tenth largest by nominal GDP and sixth largest by PPP as of 2015.32 Russia’s extensive mineral and energy resources, the largest reserves in the world, have made it one of the largest producers of oil and natural gas globally.33 The country is one of the five recognized nuclear weapons states and possesses the largest stockpile of weapons of mass destruction. Russia was the world’s second biggest exporter of major arms in 2010 to 2014, per Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) data.34

Russia is a great power and a permanent member of the UN Security Council, a member of the G20, the Council of Europe, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), and the World Trade Organization (WTO), as well as being the leading member of the CIS, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and one of the five members of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), along with Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Russia has a developed, high-income market economy with enormous natural resources, particularly oil and natural gas. It has the 15th largest economy in the world by nominal GDP and the 6th largest by PPP. As depicted in Figure A.16, since the turn of the 21st century, higher domestic consumption and greater political stability have bolstered economic growth in Russia. The GDP per capita in Russia was last recorded at $23,292.91 in 2014, when adjusted by PPP. The GDP per capita, in Russia, when adjusted by PPP is equivalent to 131 percent of the world’s average. GDP per capita PPP in Russia averaged $17,196.23 from 1990 until 2014, reaching an all-time high of $23,561.37 in 2015 and a record low of $11,173.03 in 1998.

Figure A.16 Russia’s per capita PPP GDP 2006–2015

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.com

The country ended 2008 with its 9th straight year of growth, but growth has slowed with the decline in the price of oil and gas. Non-traded services and goods for the domestic market, as opposed to oil or mineral extraction and exports, primarily drove growth. Approximately 12.8 percent of Russians lived below the national poverty line in 2011, significantly down from 40 percent in 1998 at the worst point of the post-Soviet collapse. Unemployment in Russia was 5.4 percent in 2014, down from about 12.4 percent in 1999. The middle class has grown from just 8 million persons in 2000 to 104 million persons in 2015. However, after U.S.-led sanctions since 2014 and a collapse in oil prices, the proportion of middle class could halve to 20 percent. Sugar imports reportedly dropped 82 percent between 2012 and 2015 because of the increase in domestic output.

Russia’s recession deepened in the first half of 2015 with a severe impact on households. The economy continues to adjust to the 2014 terms-of-trade shock amid a tense geopolitical context marked by ongoing international sanctions. Oil and gas prices remained low through the first half of 2015, further underscoring Russia’s vulnerability to volatile global commodity markets. The weakening of the ruble created a price advantage for some industries, boosting a narrow range of exports and encouraging investment in a certain sector, but this was not sufficient to generate an overall increase in nonenergy exports. Investment demand continued to contract for a third consecutive year.

Economic policy uncertainty arising from an unpredictable geopolitical situation and the continuation of the sanctions regime caused private investment to decline rapidly as capital costs rose and consumer demand evaporated. The record drop in consumer demand was driven by a sharp contraction in real wages, which fell by an average of 8.5 percent in the first 6 months of 2015, illustrating the severity of the recession. However, the deterioration of real wages was also the primary mechanism through which the labor market adjusted to lower demand, and unemployment increased only slightly from 5.3 percent in 2014 to 5.6 percent in the first half of 2015. The erosion of real income significantly increased the poverty rate and exacerbated the vulnerability of households in the lower 40 percent of the income distribution.

The policy response by the authorities successfully stabilized the economy. The transition to a free-floating exchange rate allowed imports to adjust to 17 percent depreciation in the real effective exchange rate during the first half of 2015, strengthening the current-account balance. Meanwhile, measures to support the financial sector appear to have contained systemic risks, and there are early signs of stabilization. Nevertheless, the pass-through effect of the December 2014 depreciation boosted inflation to levels not seen since 2002.

Even as the recession deepened in the first half of 2015 controlling inflation became the central bank’s main policy challenge. Low oil prices continue to put downward pressure on federal revenue, ushering in a period of difficult fiscal consolidation. Real public spending is expected to fall by 5 percent in 2015, notwithstanding a temporary increase in the first half of the year caused by frontloaded expenditures as part of the government’s anticrisis plan to cushion some of the fiscal consolidation impact. Falling oil revenues constrained the government’s ability to counter the decline in real income, and nominal increases in pensions and social benefits were below the headline inflation rate. This accelerated an already troubling rise in the poverty rate, which climbed from 13.1 percent in the first half of 2014 to 15.1 percent in the first half of 2015.

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan, as depicted in Figure A.17, is a country in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north and east, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the south and southwest, and the Caspian Sea to the west.

Turkmenistan has been at the crossroads of civilizations for centuries. In medieval times, Merv was one of the great cities of the Islamic world and an important stop on the Silk Road, a caravan route used for trade with China until the mid-15th century. Annexed by the Russian Empire in 1881, Turkmenistan later figured prominently in the anti-Bolshevik movement in Central Asia. In 1924, Turkmenistan became a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic (Turkmen SSR). The country became independent upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Turkmenistan possesses the world’s fourth largest reserves of natural gas resources.35 Most of the country is covered by the Karakum (Black Sand) Desert. Since 1993, citizens have received government-provided electricity, water, and natural gas free of charge.

Figure A.17 Turkmenistan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north and east, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the south and southwest, and the Caspian Sea to the west

Source: Encyclopedia Britannica.

President for Life Saparmurat Niyazov ruled Turkmenistan until his death in 2006. Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow was elected president in 2007. As per Human Rights Watch, “Turkmenistan remains one of the world’s most repressive countries. The country is virtually closed to independent scrutiny, media and religious freedoms are subject to draconian restrictions, and human rights defenders and other activists face the constant threat of government reprisal.” President Berdymukhamedow promotes a personality cult in which he, his relatives, and associates enjoy unlimited power and total control over all aspects of public life.36

The Turkmen economy, as depicted in Figure A.18, continued strong growth performance in 2012, expanding by 11.1 percent. High growth performance sustained over an extended period led to a steady increase in income levels and moved the country to an upper middle-income status. Preliminary outcomes of the annual economic developments demonstrate that the Turkmen economy remains resilient to the global uncertainties stemming from the Eurozone crisis. The GDP per capita in Turkmenistan was last recorded at $14,762.19 in 2014, when adjusted by PPP. The GDP per capita, in Turkmenistan, when adjusted by PPP is equivalent to 83 percent of the world’s average. GDP per capita PPP in Turkmenistan averaged $7,471.40 from 1990 until 2014, reaching an all-time high of $14,762.19 in 2014 and a record low of $4,221.14 in 1997.

Figure A.18 Turkmenistan GDP per capita PPP 2006–2014

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.com.

The country possesses the world’s fourth-largest reserves of natural gas and substantial oil resources. Turkmenistan has taken a cautious approach to economic reform, hoping to use gas and cotton sales to sustain its economy. In 2004, the unemployment rate was estimated to be 60 percent. However, between 1998 and 2002, Turkmenistan suffered from the continued lack of adequate export routes for natural gas and from obligations on extensive short-term external debt. At the same time, however, the value of total exports has risen sharply because of increases in international oil and gas prices. Economic prospects soon are discouraging because of widespread internal poverty and the burden of foreign debt.

The government maintains a large portfolio of social transfers and budget subsidies. Currently, all 17 subsidies have a universal character and are guaranteed until 2030, after which time the government may decide to move to a more targeted public social transfer policy. Social indicators have showed improvements commensurate with the country’s economic performance. Per the State Statistics Committee of Turkmenistan, wages and salaries have increased by 11.2 percent during 2012 compared to 2011. After adjusting for inflation, the real rate of wage increase still make up 6 percent.

The Government’s National Socio-Economic Development Program for 2011 to 2030 and the National Rural Development Program focus on inclusive economic growth while preserving economic independence, modernizing the country’s infrastructure, and promoting foreign direct investment.

Tajikistan is a mountainous landlocked sovereign country in Central Asia, with an estimated 8 million people in 2015, it is the 98th most populous country and with an area of 143,100 square kilometers (55,300 sq. mi.). It is the 96th largest country in the world. The territory that now constitutes the country was previously home to several ancient cultures, including the city of Sarazm of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, and was later home to kingdoms ruled by people of different faiths and cultures, including the Oxus civilization, Andronovo culture, Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Manichaeism.

As depicted in Figure A.19, the country is bordered by Afghanistan to the south, Uzbekistan to the west, Kyrgyzstan to the north, and China to the east. Pakistan lies to the south separated by the narrow Wakhan Corridor. Traditional homelands of Tajik people included present-day Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan.

Numerous empires and dynasties, including the Achaemenid Empire, Sassanian Empire, Hephthalite Empire, Samanid Empire, Mongol Empire, Timurid dynasty, and the Russian Empire, have ruled the area. Because of the breakup of the Soviet Union, Tajikistan became an independent nation in 1991. A civil war was fought almost immediately after independence, lasting from 1992 to 1997. Since the end of the war, newly established political stability and foreign aid have allowed the country’s economy to grow.

Figure A.19 Tajikistan is bordered by Afghanistan to the south, Uzbekistan to the west, Kyrgyzstan to the north, and China to the east

Source: Operationworld.com.

Tajikistan is a presidential republic consisting of four provinces. Most of Tajikistan’s 8 million people belong to the Tajik ethnic group, who speak Tajik (Persian), although many people also speak Russian. Mountains cover more than 90 percent of the country. It has a transition economy that is dependent on aluminum and cotton production. Its economy is the 126th largest in the world in terms of purchasing power and 136th largest in terms of nominal GDP.

Because of the economic recession in Russia, weakening of the Russian ruble and tightening of migration regulations, economic growth in Tajikistan slowed from an average of 7.5 percent a year over the past decade to 6.4 percent in the first 6 months of 2015. The U.S. dollar value of remittances, about 80 percent of which originate from Russia, fell by 32 percent in January to June 2015, compared to the same period in 2014, largely due to the sharp depreciation of the Russian ruble. The slowdown in remittances affected domestic demand, which in turn depressed growth in services, the major contributor to economic growth in the past.

Growth is projected to significantly slowdown in the medium term, with a very gradual recovery, putting Tajikistan’s poverty reduction gains of the last decade at great risk. As this trend in the economy is likely to persist in the medium term, it is even more important that Tajikistan implements sound macroeconomic policies and structural reforms that are necessary to create the foundation for more domestically generated inclusive growth, while investing in quality public services. The current situation should be an opportunity to reform the economy and to adopt new engines of growth—private investment and export—to generate more and better-paying jobs in the country.

To date, Tajikistan has done a remarkable job in reducing poverty. During the period 1999 to 2014, poverty fell from over 80 percent to about 32 percent in the country. Tajikistan’s pace of poverty reduction over the past 15 years has been among the top 10 percent in the world. However, the country has done less well in reducing nonmonetary poverty. Recently available micro-data suggest that limited or no access to education (secondary and tertiary), heating, and sanitation is the main contributors to nonmonetary poverty. These three are the most unequally distributed services, with access to education varying by income level and heating and sanitation per location.

Figure A.20 Tajikistan GDP per capita PPP 2006–2015

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.com.

As depicted in Figure A.20, Tajikistan’s GDP per capita was last recorded at $2,532.51 in 2014, when adjusted by PPP. The GDP per capita, in Tajikistan, when adjusted by PPP is equivalent to 14 percent of the world’s average. GDP per capita PPP in Tajikistan averaged $1,849.28 from 1990 until 2014, reaching an all-time high of $3,635.34 in 1990 and a record low of $1,040.23 in 1996.

The Government of Tajikistan has set ambitious goals to be reached by 2020: to double GDP, to reduce poverty to 20 percent, and to expand the middle class. To achieve higher growth, Tajikistan needs to implement a deeper structural reform agenda designed to (a) reduce the role of the state and enlarge that of the private sector in the economy through a more conducive business climate, thus increasing private investment and generating more productive jobs; (b) modernize and improve the efficiency and social inclusiveness of basic public services; and (c) enhance the country’s connectivity to regional and global markets and knowledge.

The difficult environment for doing business in Tajikistan, as well as obstacles to foreign direct investment, have discouraged private investment and limited overall investment. Averaging about 15 percent of GDP annually since 2008, total investment is low by regional and international standards.

Public investment accounts for 80 percent of the total, or 12 percent of GDP, and private investment for 20 percent, or only 3 percent of GDP—much lower than the Europe and Central Asia developing country average. The main obstacles cited by both local and foreign entrepreneurs are inadequate infrastructure, insufficient and unreliable energy supply, the weak rule of law, especially about property rights, and tax policy and administration. Increased private investment and new business development are crucial prerequisites for increased job creation.

With 20 percent of GDP and 53 percent of employment, the agriculture sector in Tajikistan offers a solid foundation for economic development. The Government of Tajikistan displays a strong commitment to the agricultural reform program, which includes the resolution of the cotton debt crisis, accelerated land reform, freedom to farm, improved access to rural finance, and increased diversification of agriculture.

Efforts are underway to make investment in agriculture more profitable, especially for exports, by enhancing access to markets and by empowering farmers through strengthening their land-use rights, improving their access to credit and inputs, and enabling them to make their own cropping decisions. The recent growth of non-cotton agricultural exports indicates the potential for growth in agro-processing, including storage of fruit and vegetables, which holds great promise for development, along with textiles and clothing.

Meeting Tajikistan’s energy demand will be an important part of the agenda to reduce poverty and create an enabling environment for private businesses. Approximately 70 percent of the population suffers from extensive electricity shortages during winter. The shortages increased considerably starting in 2009, when Tajikistan’s power network was severed from the Central Asia Power System and power trade with Central Asian countries stopped. Electricity shortages in winter are estimated to be at least 2,000 gigawatt-hours, or about 20 percent of winter electricity demand.

Tajikistan is also faced with a young and rapidly growing population. Recent estimates show that 55 percent of the population in Tajikistan is under the age of 25, making improved public services in social sectors (education, health, and social protection), as well as job creation, imperative components of Government’s Poverty Reduction Strategy.

The territory of modern Ukraine has been inhabited since 32,000 BC. During the middle Ages, the area was a key center of East Slavic culture, with the powerful state of Kievan Rus’ forming the basis of Ukrainian identity. The country is currently in dispute with Russia over the Crimean, which Russia annexed back in 2014, although Ukraine and most of the international community still do not recognize as Russian. If we include Crimea, Ukraine has a total area of 603,628 square kilometers (233,062 sq. mi.), which makes the country the largest within the entire Europe and the 46th largest country in the world. With a total population of about 44.5 million, Ukraine is the 32nd most populous country in the world. Ukraine, as depicted in Figure A.21, is a country in the CIS bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Belarus to the northwest, Poland and Slovakia to the west, Hungary, Romania, and Moldova to the southwest, and the Black Sea and Sea of Azov to the south and southeast, respectively.

Following its fragmentation in the 13th century, the territory was contested, ruled, and divided by a variety of powers, including Lithuania, Poland, the Ottoman Empire, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. A Cossack republic emerged and prospered during the 17th and 18th centuries, but its territory was eventually split between Poland and the Russian Empire, and later submerged fully into Russia. Two brief periods of independence occurred during the 20th century, once near the end of World War I and another during World War II, but both occasions would ultimately see Ukraine’s territories conquered and consolidated into a Soviet republic, a situation that persisted until 1991, when Ukraine gained its independence from the Soviet Union in the aftermath of its dissolution at the end of the Cold War.

Figure A.21 Ukraine is a country in the CIS bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Belarus to the northwest, Poland and Slovakia to the west, Hungary, Romania, and Moldova to the southwest, and the Black Sea and Sea of Azov to the south and southeast, respectively

Source: Worldtravels.com.

Following independence, Ukraine declared itself a neutral state.37 Nonetheless, the country formed a limited military partnership with the Russian Federation, other CIS countries and a partnership with NATO since 1994. In the 2000s, the government began leaning toward NATO, and the NATO-Ukraine Action Plan signed in 2002 set a deeper cooperation with the alliance. It was later agreed that the question of joining NATO should be answered by a national referendum at some point in the future.

Former President Viktor Yanukovych considered the current level of cooperation between Ukraine and NATO sufficient, and was against Ukraine joining NATO. In 2015, protests against the government of President Yanukovych broke out in downtown Kiev after the government made the decision to suspend the Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement and sought closer economic ties with Russia. This began a several-months-long wave of demonstrations and protests known as the Euromaidan, which later escalated into the 2014 Ukrainian revolution that ultimately resulted in the overthrowing of Yanukovych and the establishment of a new government. These events precipitated the Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation in February 2014, and the War in Donbass in March 2014; both are still ongoing as of December 2015. On January 1, 2016, Ukraine joined the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area with the European Union.38

Ukraine has long been a global breadbasket because of its extensive, fertile farmlands, and it remains one of the world’s largest grain exporters. The diversified economy of Ukraine includes a large heavy industry sector, particularly in aerospace and industrial equipment.

Ukraine is a unitary republic under a semipresidential system with separate powers: legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Its capital and largest city is Kiev. Ukraine maintains the second-largest military in Europe, after that of Russia, when reserves and paramilitary personnel are considered. The country is home to 45.4 million people (including Crimea), 77.8 percent of whom are Ukrainians by ethnicity, followed by a sizeable minority of Russians (17.3 percent) as well as Romanians/ Moldovans, Belarusians, Crimean Tatars, and Hungarians. Ukrainian is the official language of Ukraine; its alphabet is Cyrillic. The dominant religion in the country is Eastern Orthodoxy, which has strongly influenced Ukrainian architecture, literature, and music.

Ukraine’s GDP per capita PPP, as depicted in Figure A.22, was last recorded at $8,267.07 in 2014, when adjusted by PPP. The GDP per capita, in Ukraine, when adjusted by PPP is equivalent to 47 percent of the world’s average. GDP per capita PPP in Ukraine averaged $6,996.86 from 1990 until 2014, reaching an all-time high of $10,490.37 in 1990 and a record low of $4,462.78 in 1998.

Ukraine posted zero economic growth over 2012 and 2015 because serious macroeconomic and structural weaknesses remain unaddressed. A combination of de facto fixed exchange rate policy, loose fiscal policy together with considerable quasi fiscal subsidies in the energy sector has led to further widening of the budget and the external imbalances and threatens sustainability.

Figure A.22 Ukraine GDP per capita PPP 2006–2015

Source: World Bank, tradingeconomics.com

Top concerns for Ukraine now are the developments in the Euro zone and the state of the global economy together with resolution of the political crisis in the country. Confidence in the government and the state institutions is low. Economic growth remained weak for the last 2 years. After five consequent quotes of economic slowdown started in the second half of 2012, Ukraine’s GDP posted growth of 3.7 percent y/y in 4Q2013 driven by good harvest and low statistical base. This brought FY GDP growth to 0.0 percent (after 0.2 percent in 2012). Performance of the key sectors remained week due to weak external conditions and delays in domestic policy adjustment.