3. Operational Flexibility—Don’t Analyze What You Can’t Act On

Analytic insights have no value if they can’t be put to work. Melanie Murphy, Director of Analytics for the home goods retailer Bed Bath & Beyond, says, “If you can’t act on the model, you probably shouldn’t build it.” This chapter describes and explores dimensions of marketing and sales processes and infrastructure so managers and executives on both sides of the analysis/operations divide can properly time their investments in their respective capabilities to make sure they aren’t idle while they wait on each other.

Marketing operations limitations come in several different shapes. You may discover certain differences in customer demographics or behavior that predict purchase or some other target action. But you may lack a marketing automation platform that can react quickly enough, with sufficiently fine-grained pricing or messaging, to take advantage of these differences during relevant time windows. Or, the systems you do have may not be functioning as they should because of imperfect maintenance (a failure to whitelist your mail server, for example).

Three scenarios emerge from the conversations for this book.

1. You don’t have the marketing and sales automation machinery to execute tests or solutions for the insights you’ve developed.

2. You have the machinery, but either it’s not fully implemented or the processes that support it (for example, getting creative content developed for testing a landing page variant) are still done “the old way.”

3. You have the machinery, but there’s a line to stand in for resources, and you have to take a number.

We’ll look at each of these in turn to describe challenges you might run into and how to deal with them.

As with the need to find common analytic frameworks to drive strategic alignment discussed in Chapter 1, “Strategic Alignment,” any successful effort to match operational flexibility to analytic capability has to start with a common understanding of the operations that the analysis might impact. So, what is marketing and sales automation? What capabilities does it include? What should you get first, next, later? Lots of vendors, including big ones such as IBM, Oracle, and TeraData, as well as hundreds more, are now investing in answering these questions, especially as they try to reach beyond IT to sell directly to the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO). These vendors provide myriad marketing materials to describe both the landscape and their products, which variously are described as “campaign management systems” or even more gloriously as “marketing automation solutions.” The proliferation of solutions is so mind-blowing that analyst firms build whole practices making sense of the category. For example, Terence Kawaja’s very popular “LUMAscape” charts illustrate the relevant domains memorably and comprehensively.1

1. “Lumascapes,” Luma Partners, http://www.lumapartners.com/resource-center/lumascapes-2/.

A “Common Requirements Framework”

Yet even with this guidance, organizations struggle to get relevant stakeholders on the same page about what’s needed and how to proceed. My own experience has been that this is because they’re missing a simple “Common Requirements Framework” that everyone can share as a point of departure for the conversation. Here’s one I’ve found useful.

Basically, marketing is about targeting the right customers and getting them the right content (product information, pricing, and all the before-during-and-after trimmings) through the right channels at the right time. So, for example, a marketing automation solution, well, automates this. More specifically, since there are lots of homegrown hacks and point solutions for different pieces of this, what’s really getting automated is the manual conversion and shuffling of files from one system to the next, or in other words, the integration of it all. Some of these solutions also let you run analyses and tests out of the same platform (or partnered components).

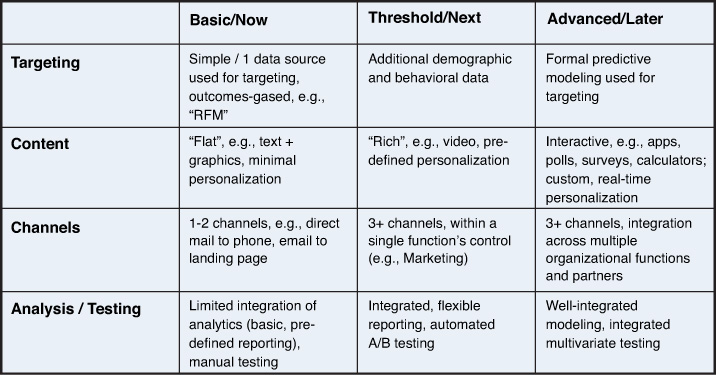

Each of these functions has increasing levels of sophistication; I’ve characterized them into “basic,” “threshold,” and “advanced.” For simple road mapping and prioritization purposes, you might also call these “now,” “next,” and “later.”

Targeting

The simplest form of targeting uses a single data source—past experience at the cash register—to decide whom to go back to, on the idea that you build a business inside out from your best, most loyal customers. Cataloguers have a fancy term for this: “RFM,” which stands for “Recency, Frequency, and Monetary Value.” RFM grades customers, typically into deciles, according to, well, how recently, how frequently, and how much they’ve bought from you. Folks who score high get solicited more intensively (for example, more catalog drops). By looking back at a customer’s past RFM-defined marginal value to you (the gross margin you earned from stuff you sold her), you can make a decision about how much to spend marketing to her.

One step up, you add demographic and behavioral information about customers and prospects to refine and expand your lists of folks to target. Demographically, for example, you might say, “Hey, my best customers all seem to come from Greenwich, CT. Maybe I should target other folks who live there.” You might add a few other dimensions to that, such as age and gender. Or you might buy synthetic, “psychographic” definitions from data vendors who roll a variety of demographic markers into inferred attitudes. Behaviorally, you might say, “Let’s retarget folks who walk into our store or who put stuff into our online shopping cart but don’t check out.” These are conceptually straightforward things to do, but they are logistically harder because now you have to integrate external and internal data sources, comply with privacy policies, and so on.

In the third level, you begin to formalize the models implicit in these prior two steps and build lists of folks to target based on their predicted propensity to buy (lots) from you. For example, you might say, “Folks who bought this much of this product this frequently, this recently, who live in Greenwich, and who visited our web site last week, have this probability of buying this much from me, so therefore I can afford to target them with a marketing program that costs X dollars per person.” That’s “predictive modeling.”

Some folks evaluate the sophistication of a targeting capability by how fine-grained the target segments get, or by how close to 1-1 personalization you can get. In my experience, there are often diminishing returns to this, often because the firm can’t always practically execute differentiated experiences, even if the marginal value of a personalized experience warrants it. This isn’t universally the case of course: Promotional offers and similar experience variables (for example, credit limits) are easier to vary than, say, a hotel lobby.

Content

Again, a simple progression exists here, for me defined by the complexity of the content you can provide (“plain,” “rich,” “interactive,” and so on) and by the flexibility and precision (“none,” “pre-defined options,” “custom options,” and so on) with which you can target the content through any given channel or combination of channels. Wayfair’s Ben Clark offered a particularly rich illustration of the cutting edge of this dimension in our conversation for this book (see Chapter 14, “Conversations with Practitioners”).

Another content dimension to consider is the complexity of the organizations and processes necessary to produce this content. For example, in highly regulated environments like health care or financial services, you may need multiple approvals before you can publish something. And the more folks involved, the more sophisticated and valuable the coordination tools, ranging from central repositories for templates, version control systems, alerts, and even joint editing. Beware, though, of simply paving cow paths—be sure you need all that content variety and process complexity before enabling it technologically, or it will simply expand to fit what the technology permits (the same way computer operating systems bloat as processors get more powerful).

Channels

The big dimension here is the number of channels you can string together for an integrated experience. For example, in a simple case you have one channel, say email, to work with. In a more sophisticated system, you can say, “When people who look like this come to our website, retarget them with ads in the display ad network we use.” (Google recently integrated Google Analytics with Google Display Network to do just this,2 an ingenious move that further illustrates why they lead the pack in the display ad world.) Pushing it even further, you could also say, “In addition to retargeting website visitors who do X out in our display network, let’s also send them an email/postcard combination with connections to a landing page or phone center.”

2. “Features,” Google Analytics, http://www.google.com/analytics/features/remarketing.html.

Analysis and Testing

In addition to execution of campaigns and programs, a marketing solution might also support evaluation and exploration of what campaigns and programs, or components thereof, might work best. This happens in a couple of ways. You can examine past behavior of customers and prospects to look for trends and build models that explain how changes and saliencies along one or more dimensions might have been associated with buying. Also, you can define and execute A/B and multivariate tests (with control groups) for targeting, content, and channel choices.

Again, the question here is not just about how much data flexibility and algorithmic power you have to work with within the system, but how many integration hoops you have to go through to move from exploration to execution. Obviously you won’t want to run exploration and execution off the same physical data store, or even the same logical model, but it shouldn’t take a major IT initiative to flip the right operational switches when you have an insight you’d like to try, or a successful experiment you’d like to scale to cover more of your customers.

Concretely, the requirement you’re evaluating here is best summarized by a couple of questions. First, “Show me how I can track and evaluate differential responses in the marketing campaigns and programs I execute through your proposed solution,” and then, “Show me how I can define and test targeting, content, and channel variants of the base campaigns or programs, and then work the winners into a dominant share of our mix.”

A Summary Picture

See Figure 3.1 for a simple table that tries to bundle all this up. Notice that, in contrast with representations such as Terence Kawaja’s LUMAscapes, it focuses more on function than features and capabilities instead of components. Also, in terms of the progression it describes, it is equally applicable to sales as to marketing.

What’s Right for You?

The important thing to remember is that these functions and capabilities are means not ends. To figure out what you need, you should reflect first on how any particular combination of capabilities would fit into your marketing organization’s “vector and momentum.” How is your marketing performance trending? How does it compare with competitors? In what parts (targets, content, and channels) is it better or worse? What have you deployed recently and learned through its operation? What kind of track record have you established in terms of successful deployment and leverage from your efforts?

If your answers are not strong or clear, then you might be better off signing onto a mostly-integrated, cloud-based (so you don’t compound business value uncertainty with IT risk), good-enough-across-most-things solution for a few years until you sort out—affordably (read: rent, don’t buy)—what works for you and what capability you need to go deep on. If, on the other hand, you’re confident you have a good grip on where your opportunities are and you have momentum and confidence in your team, you might add best-of-breed capabilities at the margins of the more general “logical model” this proposed framework provides. What’s generally risky is to start with an under-performing operation built on spaghetti and plan for a smooth multi-year transition to a fully integrated on-premise option—that just puts too many moving parts into play, with too high of an up-front, bet-on-the-come investment.

Again, remember that the point of a “Common Requirements Framework” isn’t to serve as an exhaustive checklist for evaluating vendors. It’s best used as a simple model you can carry around in your head and share with others, so that when you do dive deep into requirements, you don’t lose the forest for the trees, in a category that’s become quite a jungle.

Integrating Analytics into Operational Capability Planning

As we discussed in Chapter 1, we’ve observed three different analytic perspectives at work in marketing and sales. With marketing operations and planning for those operations sometimes organized separately from analytics groups, plans for what to build next can also often be divorced from groups that analyze and report how well existing capabilities are performing. As a consequence of this, the requirements for these systems to support ongoing analytics and testing can also be an afterthought. Even the tools themselves reinforce this balkanization. How else to explain why most modern content management systems still have not integrated testing as a native feature? It could be, for example, that the vendors behind these systems cannily play on the organizational silos. After all, it’s likely more profitable to divide and conquer by selling the CMS to the operators and the A/B testing platform after the fact to a different group.

The charter of the modern analytics group is evolving to influence not just analytic capabilities but execution-oriented ones as well. Lenovo’s Mo Chaara describes how for certain “chartered” analytic initiatives, such as determining indicators and causes for potentially “pervasive quality issues,” his group’s charge is to go all the way from exploring data for insights to standing up the platforms through which the opportunity will be realized. Generally this means being comprehensively involved at least through an operational pilot, in order to shake out all the bugs in practice. He describes this expansive role for the analyst as “the beginning of a new way of business management, where an analytics team leads the development of solutions that drive strategy,” as opposed to simply reporting and analyzing the results after they happen. Paul Magill’s newly centralized marketing intelligence function at Abbott provides another example of this modern role for the analytics group; there, Paul is counting on that team to inform the capabilities of Abbott’s investments in digital channels, and in particular to make them as relevant for brand marketing as they have been for direct efforts.

Some discussion questions:

• How in sync (or not) are your analytic and execution capabilities?

• Which one is further ahead? How, and how far?

• What’s your current plan for closing the gap?

• Is that plan an appropriate leap, or too short or too far?

• Along which dimension of execution—targeting, creative, channel, and so on—do you think your greatest opportunities lie?

• Are your current efforts aimed at this opportunity?

• If not, what can you do to adjust course?

• To what degree are you technology-constrained versus people-constrained?