16. Transformation of Marketing at the Ohio Art Company

Transformation of Marketing at the Ohio Art Company (A)

The Ohio Art Company—among America’s oldest toymakers—was headquartered in Bryan, Ohio, a small town in the northwest part of the state. Although Ohio Art made over 50 toy varieties including dolls and water toys, its flagship product was a drawing toy it had been selling for more than 52 years: the Etch A Sketch (EAS). In that time, over 100 million units had been sold to consumers in dozens of countries. Ohio Art’s slogan, “Making Creativity Fun,” demonstrated the company’s commitment to arts and crafts products. Although most of its sales came from its toy business, Ohio Art also produced and sold custom metal lithography, which contributed one third of the company’s revenues and a disproportionate share of profits.1 In recent years, Ohio Art’s toy business had experienced a bumpy ride, alternating between profits and losses throughout the 1990s and up through 2011. Product placement of EAS in the hit animated movie Toy Story was a shot in the arm for Ohio Art in 1995. In 1998, the company introduced a new doll called Betty Spaghetty, which was an initial hit with consumers, but its popularity and sales had waned over time. “Aimed at girls ages four and up, the small doll featured interchangeable limbs, spaghetti-like hair, and a variety of accessories, such as a cell phone, a laptop computer, and in-line skates.”2

Toy Supply Chain and Seasonality

Toy retailing had become more concentrated, with Walmart, Toys “R” Us, and Target accounting for the overwhelming majority of sales.3 The need for lower costs (to compete effectively in the mass-merchant channel) forced Ohio Art to shift all production of its toys to China in 2001. Making an EAS in China and delivering it to the warehouse in Bryan, Ohio, cost the company 20% to 30% less than making it on-site.4 The shift in production to Asia magnified the already high risks of introducing new products. Long shipping times and the seasonality of most toy sales meant that inventory management and tooling risks were significant. In 1998, a “‘major retailer’ abruptly canceled a $15.2 million toy order just before the holiday season. [Ohio Art] was left with a large amount of excess inventory and also was unable to cancel television advertising commitments that had been made in support of the holiday line.”5 Fortunately, in 1999, the company was again helped by the release of Toy Story 2, which featured a 30-second spot showing the Etch A Sketch. Management attributed the 20% increase in holiday EAS sales to that exposure.

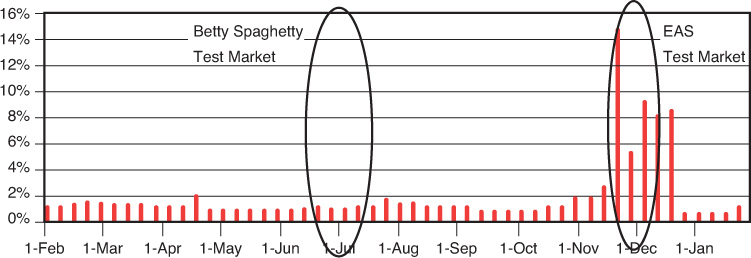

The company’s fiscal year ended January 31; November and December typically accounted for 45% of retail sales. Each of the other 10 months averaged close to 5.5% (see Figure 16-1). This same pattern was typical for almost all toys, including Ohio Art’s.

The Etch A Sketch Experiment

Although the EAS line had been promoted initially with heavy television advertising, by late 2006, advertising budgets for the EAS were below $1 million, most of which went toward reimbursing retailers for cooperative advertising. Too often, these funds did little more than fund temporary price reductions. No national television advertising had been done for several years. In late 2006, however, the company’s advertising agency proposed a new campaign to enhance the toy’s continued popularity. In part, this was due to a recent request by Target to include the EAS in its own television spot.

Although management was divided on whether an advertising campaign would be economical, it was decided to test the effectiveness of renewed television advertising through a field experiment that lasted from November 27 to December 16, 2006, a three-week period during which approximately 35% of retail toy sales normally occurred. Management intended to assess the results by comparing the test and control market sales of its largest retail customer (25% sales). This retailer had retail stores in all control markets and POS systems that allowed accurate monitoring of sales. The expectation was that observed sales increases would accrue to all retailers. Sales data from the previous year were not available because the merchant had removed EAS from its shelves for much of the year due to a pricing disagreement. The resolution of that disagreement had put EAS back on the shelves, and some of the management team thought that a sales boost through advertising would be a timely move to restore good relations between Ohio Arts and the retailer.

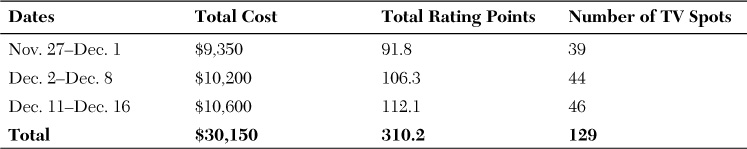

Television commercials for the EAS were aired during syndicated morning and evening talk shows, daytime soaps, and evening news programs only in Cincinnati, Ohio, during the three test weeks. There were internal concerns that Cincinnati might not be a good test market because it was in the same state as the company’s headquarters. But research showed that not only was company location not a concern for buyers, but an overwhelming majority of consumers didn’t even know that EAS was made and marketed by an Ohio company. Commercials were not aired in any other place in the United States during the test period. The breakdown of the total advertising spend in the three weeks is provided in Table 16-1. The cost of working with an outside agency to develop the test EAS commercials was $75,000. The media spend called for more than 100 spots, each with an average rating of 2.7 to be broadcast over the three weeks.6 The $30,150 media spend in Cincinnati would be equivalent to a $5 million national budget.

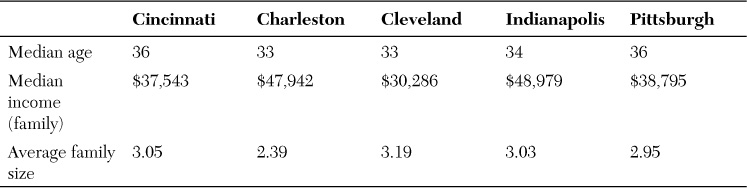

Four other cities—Charleston, South Carolina; Cleveland, Ohio; Indianapolis, Indiana; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—were chosen as controls to evaluate whether the EAS advertising led to increased sales (see Table 16-2 for city demographics). In choosing test market cities, several factors should generally be considered. First, the test city (or cities) must reflect market conditions in the product’s market area, whether it was local, regional, national, or global. No city could represent all market conditions perfectly, and success in one city did not guarantee success elsewhere. Typical criteria for good test markets included similarity to planned distribution outlets: representative population size, demographics, income, purchasing habits, and freedom from atypical competitive activity.7

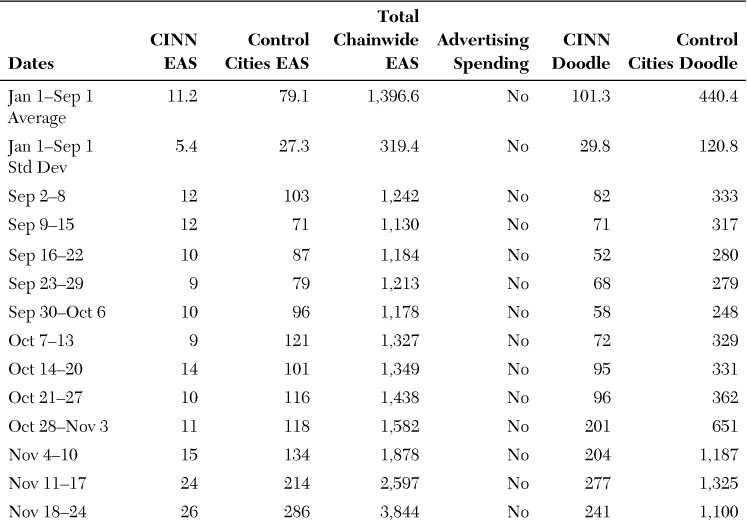

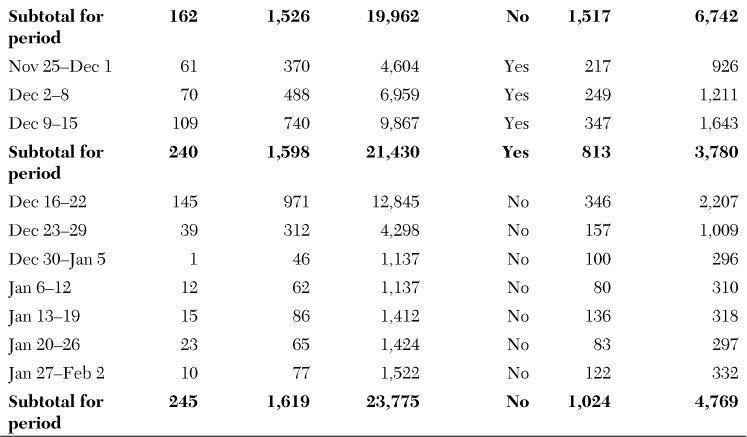

The greater Cincinnati area represented about 0.7% of the U.S. population. The average population of the control cities was around 2 million, which represented about 0.6% of the U.S. population. See Table 16-3 for sales data for EAS and another new Ohio Art product, Doodle Doug, in Cincinnati and the four control cities at selected stores of the major mass merchant.8 Doodle Doug was not advertised, but sales were tracked in the cities as an additional control in interpreting the results.

Source: Ohio Art. Used with permission.

Table 16-3 EAS and Doodle Doug Weekly Unit Sales in Test and Control Cities (1/1/05–2/2/07)

One Ohio Art executive worried that the test would be difficult to read and suggested that a split-cable test9 could be implemented in April of the following year for about $500,000. He believed the estimate of the projected sales lift from such a split-cable test would be much more accurate.

The suggested retail price for EAS was $12.99. The Travel, Pocket, and Mini Etch A Sketch were less expensive at $8.99, $4.99, and $2.99, respectively. Given unit sales for each product, the weighted average of all EAS products sold in the holiday time period was $10.00. It was this $10.00 price that was suggested for use in calculating the percentage increase required for a national campaign. The suggested retail price for Doodle Doug was $14.99. The company’s average gross margin for the EAS products was 58%, and the average retail margin was 36%. (See Figure 16-2 for pictures of the EAS and Doodle Doug.)

The Betty Spaghetty Experiment

In mid-2007, the company implemented another field experiment for a revamped Betty Spaghetty product line. The test had three objectives: (1) estimating consumer demand for the revised Betty Spaghetty line, (2) testing whether advertising could increase sales (and profits) obtained for the redesigned Betty Spaghetty, and (3) convincing the merchandise manager at a mass-merchant chain that those sales of Betty Spaghetty would justify the allocation of shelf space. For the Betty Spaghetty experiment, television and radio commercials were aired in Arizona for four weeks from June 17, 2007, to July 14, 2007. The company purchased 600 gross rating points (GRPs) for the television advertisements for a total cost of $31,500. The ads were aimed at girls between the ages of two and eleven and were aired on local cable channels, such as Nickelodeon and the Cartoon Network. Management also purchased 64 GRPs for radio commercials for a total cost of $8,022. The radio commercials were aired during morning and evening commutes. Each of the television and radio programs selected for the commercials reached about 1.8% of the population in Phoenix. The cost of developing the commercial through an outside agency was $150,000.

Management estimated that an equivalent ad budget for eight to ten weeks of preholiday advertising, factoring in certain economies as well as the higher seasonal cost of media, would be approximately $3 million. The average retail selling price of Betty Spaghetty during the test was about $15.00. Retailer and Ohio Art margins were about the same as for EAS, 36% and 58%, respectively. Given that some time would be required to read the test, obtain shelf space, and ship product to stores, management estimated that the four-week test market sales period represented about 10% of the total remaining sales potential for the year.

Table 16-4 reports weekly sales in 23 Arizona stores (test) and in 24 stores of the same mass merchant in California (control) for two versions of Betty Spaghetty. The stores represented 50% of the retailer’s Arizona sales and 10% of California sales, respectively. Arizona and California represented 2% and 12%, respectively, of the retailer’s national sales, and that same retailer was expected to account for 25% of total Betty Spaghetty sales. Management intended to use the test to help estimate Betty Spaghetty sales with and without advertising.

Source: Ohio Art. Used with permission.

Table 16-4 Weekly Unit Sales of Betty Spaghetty in Test and Control Cities

Transformation of Marketing at the Ohio Art Company (B)

In March 2012, the Ohio Art Company, best known as the manufacturer and marketer of the classic toy, Etch A Sketch (EAS), had been distracted from its efforts to shift its marketing emphasis from traditional mass-marketing channels to more targeted digital marketing. Management believed such a shift would be necessary for the company to thrive in the next decade. The distraction came from the media attention surrounding recent comments made by a campaign manager of Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney. Having been thrust into the middle of a political controversy, Ohio Art needed to decide how (and whether) to react to the growing media attention.

Distraction or Opportunity?

When asked how a campaign might change tactics from primary to general elections, Romney’s adviser Eric Fehrnstrom replied, “You hit a reset button for the fall campaign. Everything changes. It’s almost like an Etch a Sketch. You can kind of shake it up and we start all over again.”10 The result was a media firestorm. Ohio Art received numerous calls from the media, and management knew it had to decide on a plan.

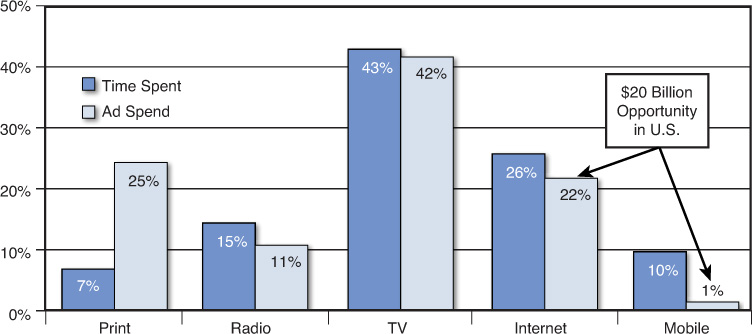

Management was concerned that investing time and financial resources to leverage the media attention might take resources away from the company’s new star product: nanoblock construction toys. Because it appealed to a wide range of ages, it would be a great candidate for promotion through digital media. For both nanoblock and the traditional EAS line, digital, social media, and online retailers offered opportunities Ohio Art had yet to explore. Figure 16-3 suggests that there was significant room for further growth in both Internet and mobile advertising, due to the gap between the percentage of time consumers spent with Internet and mobile devices and the percentage of dollars advertisers devoted to these media.

Source: Adapted from Mary Meeker, “Internet Trends,” Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers presentation transcript, D10 Conference, May 30, 2012, 17, http://www.scribd.com/doc/95259089/KPCB-Internet-Trends-2012 (accessed July 26, 2012).

Figure 16-3 Percentage of time spent using media versus percentage of advertising spend, 2011

In addition to the Internet search and display ads, there were rapidly emerging opportunities to promote through Amazon.com and social media. Social media was particularly intriguing because management thought that outlet might offer new revenue models for the EAS brand. Up until this point, the EAS brand had been mainly leveraged through an increasing number of product variants (Figure 16-4), and the productivity of introducing more EAS product extensions seemed limited. Over 150 million EAS-related products had been sold by mid-2012.

Martin Killgallon, Ohio Art’s VP of marketing, thought he could capitalize on the iconic nature of the brand by exploring partnership opportunities with other marketers. For example, the company had licensed iPhone and iPad covers that gave those devices the appearance of the EAS. iPad and iPhone mobile applications also mimicked the action of the EAS on the iPad and iPhone screens. These EAS apps, offered through Apple, Amazon, Google, and Barnes & Noble, had over 1.3 million downloads between mid-2010 and mid-2012. And interest in the timeless toy did not seem to be slowing down. In May 2012, a California start-up company created an accessory called “Etcher” as part of a project with Ohio Art: an iPad case styled after the EAS. It consisted of a bright-red plastic case with two familiar-looking knobs that were used for drawing horizontal and vertical lines. The system interfaced with an iOS app that replicated the toy’s drawing experience. The iPad version allowed users to save and share their work with others on social networks or simply shake the screen to erase their creation and start over.

The company typically negotiated a royalty payment of 5% to 10% of gross revenue for licensed products such as this. The image of the EAS product was also often used in advertising as a prop, conveying fun and creativity in the context. Sometimes Ohio Art paid to be included (such as in the Target holiday commercials), and sometimes the company granted permission in return for expected favorable exposures (like the ESPN and BMW Mini commercials). Management thought there was more the company could do to capitalize on the high brand recognition and nostalgia associated with the EAS product, but it was unsure exactly what to do and how it might be monetized.

A Shift in Strategy

Ohio Art made shifts in all aspects of its marketing mix in reaction to developments in the toy industry and the growth of online retailing. Management believed these shifts were investments that would make Ohio Art a stronger competitor in the upcoming years.

Product

Instead of designing toys from the ground up and investing in its own tooling, Ohio Art began looking to license toys for exclusive distribution that were developed by other international toy companies or smaller entrepreneurial toy companies that were trying to gain access to stronger distribution and marketing capabilities. With this approach, focusing on new channels and monitoring marketing investments, the company believed it could reduce the risk of introducing new products. Early signs were that the strategy was working at least with its new nanoblock product, which seemed to have a lot of potential. Other licensed products included K’s Kids (infant and toddler toys) and Clics (construction) for younger children and Air Picks (an “air guitar” toy that played famous guitar riffs) for preteens and older kids.11

Channels

The traditional line of products (EAS and Doodlesketch) was stocked by the three largest toy retailers—Walmart, Target, and Toys “R” Us—as well as a number of other mass and discount retailers, including dollar stores and drug stores. For the new line of licensed products, including nanoblock, the company was shifting to specialty toy stores, plus Toys “R” Us and a few bookstores, such as Barnes & Noble and Amazon.com. Management believed that attempting to distribute the new products through mass merchandisers would reduce the enthusiasm of the specialty channels (including Toys “R” Us) to stock and promote these items. Also, broadening the distribution channels would make the company less vulnerable to sudden changes in stocking, merchandising, and promotion decisions by individual retail chains. By mid-2012, approximately 1,100 accounts stocked at least some of the nanoblock line. Of those, most were specialty toy retailers or accounts such as Urban Outfitters or Barnes & Noble, which also sold hobbies and toys. Toys “R” Us and Amazon were expected to account for 65% of nanoblock units sold in 2012.

Pricing, Discounts, and Margins

One of the reasons for moving to new channels was an attempt to escape the relentless price pressure, “unauthorized deductions,” and promotional allowances required by large retailers. Specialty toy retailers tended to price products to earn 50% margins. These independent toy retailers were serviced by manufacturer representatives who typically earned commissions of 10% for sales to specialty stores. Mass retailer margins were lower. For a heavily promoted item, they were 35% or so, and for Ohio Art products, they were closer to 45%. Manufacturer representative commissions to this channel were lower: 4% to 5%. Ohio Art was determined that the new product line would not be subject to the same price pressure as the traditional line and intended to discontinue retailers that did not respect the suggested retail price levels.

Marketing Communications

Historically, sales of the core EAS line had increased in response to such publicity as the featured role in the movie Toy Story, but the gains had been short-lived and might have been due to retailer reactions—more displays, better shelf space, fewer out-of-stocks, and the like—as much as consumer demand. Finding efficient ways to promote the line of Ohio Art toys was an ongoing challenge. Traditional marketing channels were not growing sales of EAS, and the nanoblock line was an impetus to try new strategies.

Nanoblock History

Developed and manufactured by Kawada and first sold in Japan in October 2008, nanoblock allowed users to build detailed, intricate models because of their tiny size (Figure 16-5). The blocks, which were about one eighth the size of other popular building bricks, were made from high-quality ABS plastic and featured a double-ridged backing that enabled the tiny pieces to fit together almost seamlessly. They appealed to various age groups because of the variety of building sets offered.

Source: Ohio Art. Used with permission.

Figure 16-5 Sample nanoblock sets (suggested retail prices $9.99, $12.99, $19.99, and $164.99)

Because of the blocks’ instant popularity in Japan, large Japanese retail chains had dedicated much shelf display space to nanoblock. In addition to its regular lineup of products, Kawada also offered licensed products and special-edition products. The company also regularly added new items to its catalog, sometimes based on user-submitted ideas.

In late 2011, Ohio Art conducted an online survey to evaluate the demographics of its core customers. The survey revealed that almost 90% of its purchasers were between 25 and 54 years of age.12

With this valuable information about buyers, Ohio Art could now make informed decisions about marketing dollars for nanoblock. Specifically, Amazon aimed to use data, technology, and expertise to put the most appropriate products in front of the most qualified and receptive potential buyers. Amazon had built proprietary merchandising technology that allowed it to present a fully customized store to every consumer who visited its website. Companies selling on Amazon benefitted from Amazon’s commitment to drive sales by putting the right products in front of the right customers.

A study of online shopping behavior reported that Amazon.com was the source used most frequently for product reviews and ratings. Amazon was used by 58% of respondents, compared with 45% for other retailers (such as Walmart and Best Buy), 41% for search engines (such as Google and Bing), 32% for manufacturers’ websites (such as Nike and Lego), 25% for review sites (such as Epinions and CNet), 11% for Facebook, and 7% for Twitter.13

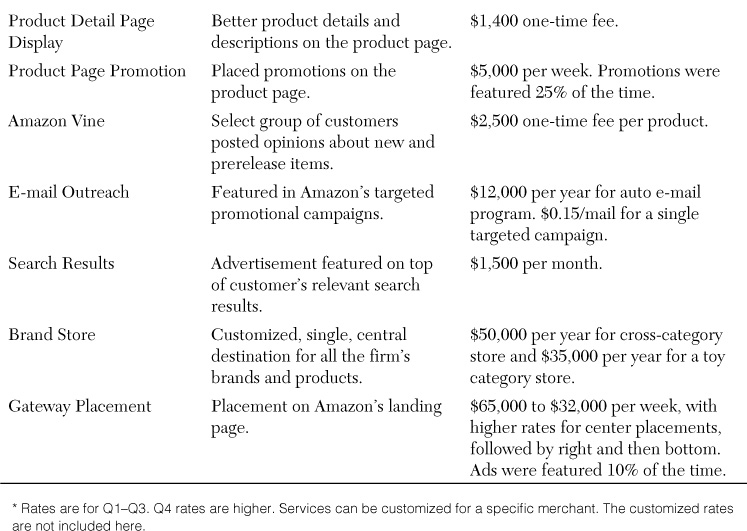

Amazon also offered a variety of targeted advertising options (see Table 16-5 for a description of the typical merchant services offered by Amazon.com) with rates that generally doubled for the toy category in the last quarter of 2011.

According to Larry Culp, an Ohio Art sales rep, the company had always had a consistent presence on Amazon due to the EAS products. But the company had not done much to promote new products on Amazon until the debut of nanoblock. Amazon, like many technology-driven sites, used algorithms and collaborative filtering to determine search results’ relevance. Collaborative filtering was a process used to generate product recommendations by matching the purchase histories of many different users. Without a minimum purchase volume, these recommendation algorithms did not have enough history to generate relevant recommendations for nanoblock.

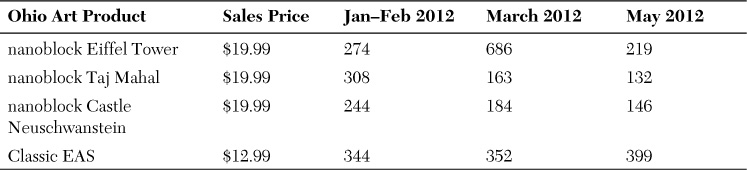

One way the company was able to increase the potential for relevant recommendations was through Amazon’s “Gold Box” promotion, where items were offered at reduced prices for an hour or two on a given day. Ohio Art decided to fund a promotion for its Eiffel Tower nanoblock set in the “Lightning Deals” section of Gold Box on March 4, 2012 (see Table 16-6 for sales data on select products). Companies paid Amazon to promote their products this way; fees were determined by the number of units companies made available for the deal multiplied by the discount (versus Amazon’s normal price). In this way, companies were challenged to forecast properly; an overestimation would result in higher promotional costs while an underestimation would result in foregone sales. These “Lightning Deals” increased the number of user clicks on the nanoblock product, thereby increasing the relevance of Ohio Art and nanoblock. That, in turn, increased the number of appearances for Ohio Art’s products even after the promotion ended. Ohio Art sold all 300 Eiffel Tower sets it offered at $12.99 in the “Lightning Deal.” The rest of March volume was sold at the regular $19.99 price.

Finally, Amazon charged suppliers a 10% cooperative advertising fee. This fee was justified by Amazon providing search capabilities and using Google AdWords/Microsoft AdCenter to get top results in searches for merchants’ products. For example, the top advertised spot in a Google search for “nanoblocks” was the Amazon.com link to Ohio Art’s products. Ohio Art was trying to determine if Amazon was a great new channel or if the challenges associated with it would be just as tricky as those it faced in dealing with traditional retailers.

Opportunities

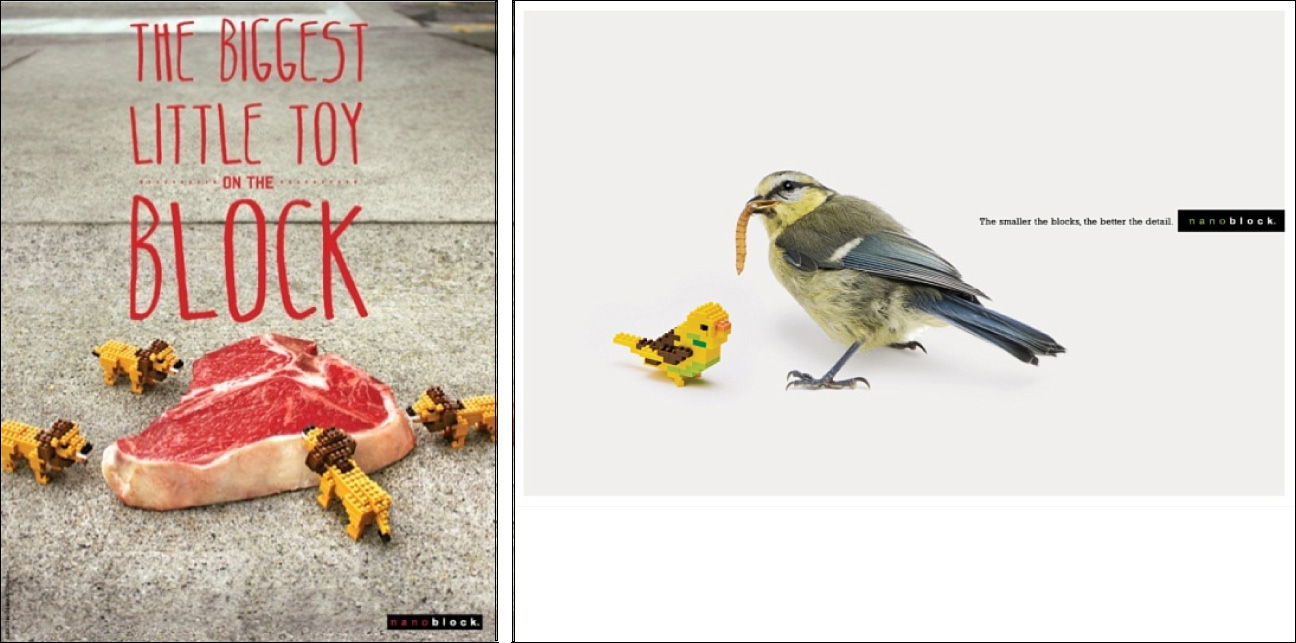

EAS sales were stagnant, but nanoblock sales were growing. The targeted-audience data about nanoblock’s customers coupled with a taste of Amazon’s variable pricing motivated management to consider engaging in other new media. Ohio Art’s ad agency recommended advertising that was playful and sophisticated for the adult audience. And the Amazon sales empowered management to recognize that it could push for positive return on investment rather than financing a large traditional ad campaign and then sitting around hoping for results. The new model of testing several tactics, discontinuing the ones that did not work, and honing the definitive successes was much more appealing—for all products, not just nanoblock.

Ohio Art utilized its Facebook.com/EAS page primarily for polls and factoids. Posts ranged from “Fun Fact: World’s Largest #EtchASketch weighs 300lbs” to “Does this expertly sketched Mona Lisa make you smile or pout?” These efforts earned it over 7,000 fans by mid-2012. For the nanoblock Facebook page, Ohio Art produced a series of targeted poster ads (Figure 16-6), special offers, and announcements about fun things that were going on. With nanoblock in particular, the company attempted to create a forum for fans to communicate with each other, asking questions and sharing creations. The videos were quite popular on the nanoblock USA Facebook page, resulting in over 3,000 fans by mid-2012.

There were several ways that companies could use blogs to promote their products. In 2010, Google Blogger introduced BlogSense accounts. Companies would pay for advertising on blogs that Google determined were related to their products. A percentage of the proceeds would go to the blogger. Of particular interest to Ohio Art was the fact that “Mommy Bloggers” had recently become very popular. Top Mommy Bloggers had thousands of daily visitors to their sites, many of whom were avid, loyal readers who deeply valued the writer’s opinions. Companies could create incentives for these bloggers to promote or review their products on their blogs, which Ohio Art pursued in 2010 and 2011. The venture resulted in over 350 websites creating permanent links to the Ohio Art sites—http://www.world-of-toys.com/ (the retail website) and www.OhioArt.com. By mid-2012, the company was evaluating whether to attempt to convert certain Mommy Bloggers into affiliates. Affiliates would link to Ohio Art’s website and receive commissions on sales that resulted from those click-throughs. Company-sponsored events, such as luncheons to demonstrate new products, functioned as forums to inform and entertain 20 or so bloggers at a time. The success of these small events was one argument for considering larger events (for example, inviting 350 bloggers to events sponsored by third parties or sponsoring booths at blogger conventions).

Ohio Art had also developed an interest in Pinterest, a content-sharing website where users could create, manage, and share theme-based “pinboards.” Users could browse other users’ pinboards, follow other pinners, and repin images to their own collections. Pinterest allowed users to share their pins on Twitter and Facebook, and with more than 12 million users (more than 80% female), it was the fastest social media site in history to break 10 million unique visitors.15 Users typically pinned things such as recipes, décor, children’s toys, and do-it-yourself crafts. But by the middle of 2012, Pinterest had not yet been explored by Ohio Art.

Overall website traffic was of interest to the company because direct-to-consumer sales represented the highest-margin sales and also because Ohio Art controlled that consumer experience completely, from product copy to price. As of mid-2012, search engines referred 22% of visits to the site. Thanks to the bloggers, there were 365 sites linking to OhioArt.com and 110 sites linking to World-of-Toys.com. Of the search-generated traffic, Ohio Art accounted for 25% of visits and some version of “Etch A Sketch” almost 40%.16

Ohio Art had e-mail addresses for approximately 18,000 customers, which were primarily collected from orders placed on the company’s website. Many of those orders were for bulk quantities, intended for events where the number of products a customer needed exceeded what a local store might keep in stock. Ohio Art had used these e-mails to send new product announcements and promotional codes to encourage orders from its website.

Conclusion

Management at Ohio Art was convinced that finding marketing investments that produced trackable, positive returns would be the key to its future success. It was no longer acceptable to take the risks associated with expensive national television ad campaigns and the associated inventory and receivables risk required to support broad retail distribution. The new philosophy was that as returns could be demonstrated, marketing investments could be rapidly scaled behind successful campaigns.

So, when Mitt Romney’s campaign manager said the candidate’s platform was “...almost like an Etch a Sketch,” the Ohio Art team had a decision to make: either have its staff and ad agency jump into social media to capitalize on the opportunity or stay the course with other targeted efforts.

Endnotes

1. “The Ohio Art Company,” International Directory of Company Histories, vol. 59, (Farmington Hills, Michigan: St. James Press, 2004).

2. “The Ohio Art Company History,” http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/the-ohio-art-company-history/ (accessed June 8, 2012).

3. Walmart had the highest market share at about 25%, followed by Toys “R” Us at 17%, and Target at 12%.

4. Joseph Kahn, “Ruse in Toyland: Chinese Workers’ Hidden Woe,” New York Times, December 7, 2003.

5. http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/the-ohio-art-company-history/.

6. One rating point was equal to 1% of the total population in a given area.

7. Charles W. Lamb, Joseph F. Hair, Carl D. McDaniel, and Daniel L. Wardlow, Essentials of Marketing (Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College Pub., 1999).

8. Unit sales figures are not provided in some weeks because EAS was not carried by the mass merchant in these weeks due to disagreements over price points.

9. Split-cable testing systems allow for delivery of separate advertising campaigns or a different level of advertising exposures to different groups of households within a given market and tracked purchases through consumer diaries or other panel data. This eliminated differences in retail environments, competitive activity, and other market characteristics among test and control groups.

10. Sam Stein, “Mitt Romney Platform ‘Like an Etch A Sketch,’ Top Spokesman Says,” Huffington Post, March 21, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/21/mitt-romney-etch-a-sketch_n_1369769.html (accessed July 23, 2012).

11. See the Ohio Art website for a complete listing of individual products: http://www.world-of-toys.com/category_s/58.htm (accessed July 30, 2012).

12. Christopher Tan is a self-proclaimed “nanoblock enthusiast” from Malaysia. He wrote a blog specifically dedicated to the product. See his post “Why nanoblock Is Cool!” September 21, 2011, http://www.inanoblock.com/2011/09/why-nanoblock-is-cool.html (accessed July 30, 2012) to understand more about the product and what types of consumers were interested in it.

13. “The 2011 Social Shopping Study,” Power Reviews, June 2011, p. 14, http://www.powerreviews.com/assets/download/Social_Shopping_2011_Brief1.pdf (accessed July 24, 2012).

14. See the Facebook page for examples of video and poster ads created by the company advertising agency: https://www.facebook.com/nanoblockUSA.

15. Josh Constine, “Pinterest Hits 10 Million U.S. Monthly Uniques Faster Than Any Standalone Site Ever—comScore,” February 7, 2012, http://techcrunch.com/2012/02/07/pinterest-monthly-uniques/ (accessed July 24, 2012).

16. “Statistics Summary for OhioArt.com,” http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/ohioart.com (accessed July 24, 2012).

Assignment Questions

1. Why did the company think it might be a good idea to advertise the EAS products? What does the experiment tell you? How would you decide whether the more reliable and more expensive split-cable experiment would be worthwhile?

2. How does the EAS experiment compare with the Betty Spaghetty experiment? In your opinion, which experiment is more suitable for evaluating whether an advertising campaign is effective?

3. Use the test results to forecast sales for Betty Spaghetty, and prepare a production order for the factory in China.

4. Evaluate the Amazon.com promotion for nanoblock. Will such promotions lead the way or get in the way of distributing through independent toy stores?

5. Which products and what kind of social media campaigns do you believe have the most potential for Ohio Art? What actions would you propose in response to the media reactions to the comments by Romney’s aide?

6. How might the company capitalize on the EAS’s iconic brand status?