39. “WHAT DO I DO WITH MY HANDS?”

WHATEVER YOU DO, avoid the “fig leaf” pose in which the portrait subject holds both of his hands together over his crotch. Under no circumstance should you use it. Ever.

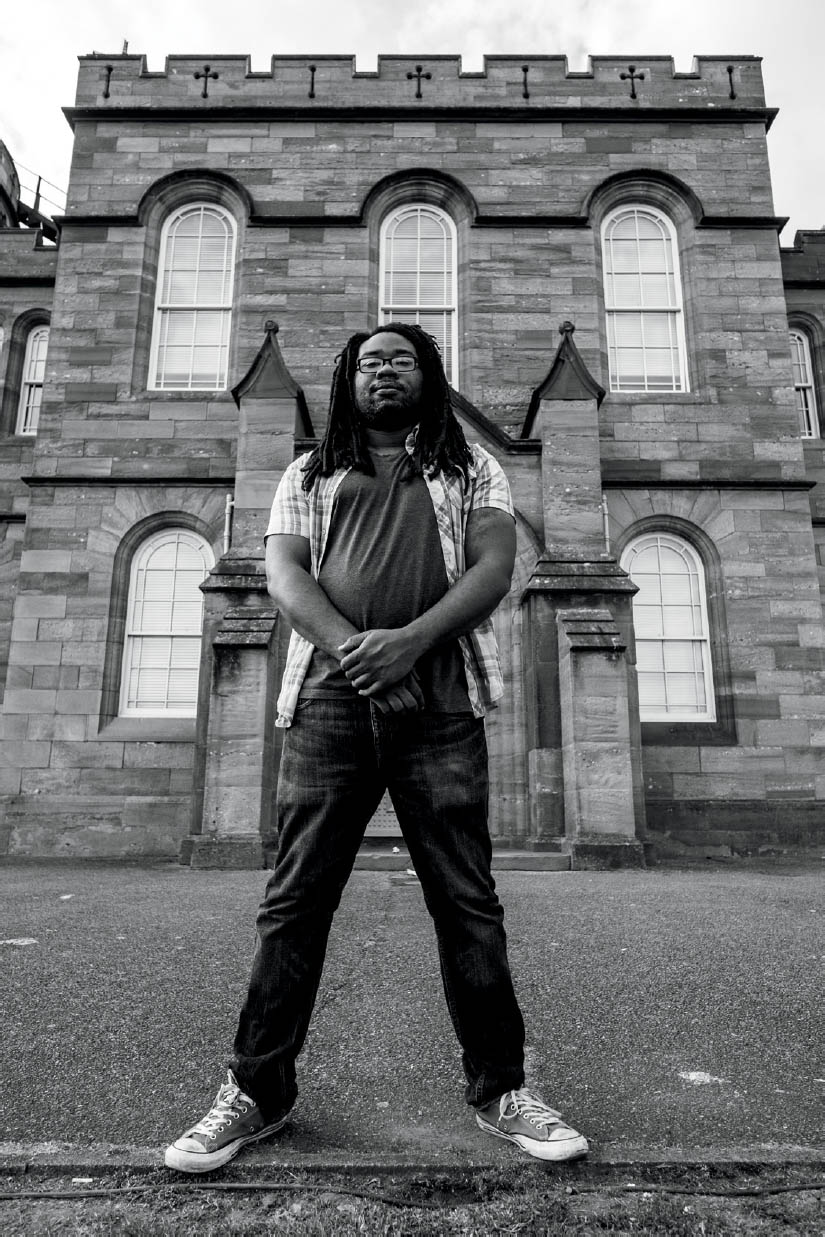

Alright, so I might be a bit hard on the “fig leaf” pose, but without any instruction, many portrait subjects (especially males) resort to using this very common hand position because they’ve seen it before or believe it to be the most formal way of posing their hands (Figure 39.1). Certainly, it has its uses—it stresses formality, seriousness, and, when combined with a low angle, intimidation—but it can also be a bit unflattering and uninteresting.

So, what do you do with your subject’s hands? The simple answer is to try to make them seem natural. For general portraiture, I encourage the subject to relax physically and see where their hands (and arms) fall. At this point, you can coach them to improve the appearance of the hands. Just as the “fig leaf” pose can get a little old, so can arms hanging down at your subject’s sides. It’s good to give the hands something to do.

39.1 The “fig leaf” pose is one that, if done well, will probably go unnoticed. However, in many cases, it’s a good way to direct your viewer’s attention to the subject’s midsection and crotch.

ISO 400; 1/550 sec.; f/4; 14mm

My go-to hand and arm positioning is to have the subject cross their arms (Figure 39.2). You’ll like it or you won’t, and that’s fine. However, crossed arms are useful for everything from relaxed, candid-like portraits to serious, dramatic-looking images. The thing I like the most about crossed arms is that they make the subject look confident, regardless of whether the face suggests joy or sternness. However natural crossed arms may be for a portrait, one thing to avoid is the subject tucking their hands behind their arms (Figure 39.3). Coach the subject to bring their hands out and bend them up into the elbows (Figure 39.4). This will appear more relaxed and relieve visual tension created by the missing hands.

For more relaxed portraiture, I also suggest having the subject place his hands in his pants pockets (Figure 39.5). This is an especially natural thing to do for male subjects. However, I make sure they don’t stick their hands in so far that the hands disappear at the wrists (Figure 39.6). Instead, I leave a portion of their fingers emerging from their pockets, indicating that they do have fingers. This also helps keep the subject from looking uptight and nervous.

Speaking of fingers, photographers go back and forth on what to do with them. It’s important to keep your subject from holding their fingers too tightly together. Discourage your subject from clenching a fist unless it is an essential part of the portrait. Likewise, avoid hands in which the fingers are spread too far apart. Fingers are best when they appear comfortably spaced from each other (Figure 39.7).

39.2 Having your subject cross their arms gives them something to do and establishes a level of attitude that, when combined with the right content, speaks volumes about their personality.

ISO 100; 1/80 sec.; f/11; 22mm

39.3 Avoid allowing your subject to stuff their hands inside their arms when crossing them. Not only does this leave the hands hidden, it also can convey a sense of nervousness or anxiety.

ISO 400; 1/450 sec.; f/2; 90mm

39.4 Instead, coach your subject to bring their hands out from behind their arms, and further give their arms dimension by turning the wrist up so the fingers point somewhat toward the subject’s shoulders.

39.5 I wanted this portrait conservation director Jason Wrinkle to convey his personality, so I coached him to put his hands in his pockets. He then hooked his thumbs into his pockets, which reflected his background growing up close to agriculture and as a cowboy.

ISO 100; 1/2500 sec.; f/2.8; 55mm

39.6 It’s the little things that count. Coaching the male subject to pull some of his hand out of his pocket would allow him to relax his arm more and separate it from his body.

ISO 200; 1/160 sec.; f/4.5; 175mm

39.7 The subject’s right hand seems relaxed in this environmental portrait—it’s not clenched, nor are the fingers tightly pressed together—exactly the visual suggestion I wanted to create for the director of an outdoor museum.

ISO 200; 1/320 sec.; f/2.8; 145mm

In many cases, you’ll more than likely coach the subject on what not to do with their hands, and they’ll pick up on it. Regardless of how well they accept that coaching, you’ll need to keep an eye on their hands to avoid those problematic issues, including awkward placement and letting them disappear behind other appendages, clothing, etc. One solution that really trumps them all (but, only if the portrait calls for it) is to give the hands something to do. As complicated as it makes other considerations of a portrait, putting something in the subject’s hands is a great way to create a natural presence for the hands and convey a narrative about your subject (Figure 39.8). Consider a cowboy holding a rope. He knows how to hold the rope, so it visually strengthens the visual notions presented in the photo. Of course, you don’t necessarily have to make your subject hold something in their hands; you could place them up against a rail and have them hold onto it or drape their arms and hands over it, for example (Figure 39.9). There’s an unending pool of options for this technique. However, be conscientious of how well the prop fits the subject. If it doesn’t, you’ll know it, they’ll know it, and viewers will notice something is awkward about the portrait.

Lastly, all this talk about hands and fingers makes it seem like they need to be in every shot. However, when you need a change of pace, a different shot perspective, or you just keep getting frustrated with the hands, it’s a good idea to switch gears and take them out of the shot altogether. Move from a medium shot to a head shot, using the frame to compose them out (and to provide your subject another “look”). Have your subject hold her hands behind her if the portrait style allows. You’re going to have to photograph hands, but it’s nice knowing that you can reduce the amount of stress surrounding the concept of photographing them by simply moving on to another type of shot or moving them out of the frame in a similarly appropriate manner.

39.8 For this conservationist’s portrait, I had him hold onto his binoculars, which gave his hands something to do. Likewise, doing so paired well with the direction he was looking—up, as if he was ready to take a closer look at a bird at a moment’s notice.

ISO 400; 1/250 sec.; f/4; 155mm

39.9 Draping an arm and hand over a railing offers new composition, new attitude and emotion, and it creates diversity among your shoot’s overall take.

ISO 400; 1/950 sec.; f/2; 90mm