Staying afloat

You are launched. You have premises, even if it is your own home. You have started selling and now must produce the goods. You may have raised money to help to finance the business. So what next? Staying afloat is the name of the game. Learning to live within the income your sales bring is a hard task, but one that has to be learned. A survey by Dun & Bradstreet found that some of the most common problem areas contributing towards failure are taking on contracts at too low a price, delays in receiving payments and being caught up in the cash flow problems of a larger company.

For some, it is easy: this could apply to you if your sort of business is consultancy, or design, or some other type of work where the overheads can be contained, at least until the time comes for expansion. For others, there is this point to strive towards before your business is truly afloat. This is known as the break-even point and is the point at which the contribution your sales bring is large enough to cover the overheads of your business, for example rent, rates, telephone and some employee costs.

When you see explanations of the break-even point in textbooks, it seems straightforward. Your business struggles towards the level of sales you find from the laid-down formula and once you have reached there, your business is ticking along nicely. In reality, break-even point is not like that at all. It has a most disconcerting habit of moving; as sales increase, so inevitably do the pressures on the business to get the job done. One way to ease the pressure is to increase the overheads and so the cycle continues. Trying to hit a moving target is notoriously difficult; and so is struggling to break even.

To stay afloat in the longer term requires more than being permanently at break-even; you need profits. These can be used to develop new products and markets as existing ones mature and decline.

These are the problems. What about the solution? Clearly, increasing the quantity and value of the sales are top priorities, as well as containing costs. But these take time. The business needs a breathing space to allow sales to develop. To allow yourself that leeway, you must control the business. And cash control assumes the major role in this. Your business will stay afloat (in the short term) if the money goes around; you hope you can keep it going long enough for sales to reach that moving target and get to break-even. You cannot do it for ever; at some stage, it will be clear that your business must raise more money or it will fail. If you are unable to get more funds, you do not want to reach the point of trading illegally, and you do not want your crash to take other small businesses with you. You have to recognise the warning signs (p. 358).

Any well-run business should be interested in cash control, whether struggling to break even or already well into profit. Making the cash go round more efficiently helps to increase your profits. Controlling cash is essentially a question of controlling debtors (that is, people who owe you money), creditors (that is, people to whom you owe money) and stock (including work in progress).

What is in this chapter?

Break-even point

One management technique you should get to grips with is break-even point. This assumes extreme importance for the sort of business that makes losses initially; possibly, you may raise money to cover that loss-making period or find it yourself. What you are working towards is the point at which the contribution (strictly, gross margin) that you make from sales is sufficient to cover the overheads (also called indirect or fixed costs).

Overheads are the cost of setting up the structure of your business. For example, the cost of your premises does not rise and fall with the quantity of sales you are making. In the long run, you could move to cheaper premises, but this is a major upheaval. In the meantime, this overhead cost is fixed. The value of your sales needs to be built up to the level that contributes to the expense of the premises.

Other examples of overheads are insurance, the cost of equipment – such as cars and computers – heating and lighting, and the telephone. One vexed problem is whether employees are a fixed cost or not. For most businesses, they will be, certainly for a few months. See p. 232 for more about the cost effect of employing people.

How to work out your break-even point

To do this you need to know:

- gross profit margin;

- total cost of overheads.

If your product or service is the same item sold many times, you can work out the gross profit (or contribution) on each item sold. The gross profit on each item is the selling price less the direct cost of each item. Direct costs are those items that you only have to pay for because you make a product or provide a service, for example raw materials.

However, if the product can vary, work out the gross profit for one month’s sales, say, and use this to find your gross profit margin.

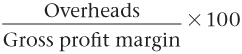

The formula for break-even point of sales is:

This gives you the number of items you must sell to cover the overhead costs (see Example 1 overleaf).

or

Gross profit margin is the gross profit divided by the value of sales times 100. This formula gives you the value of sales you must make to cover the overhead costs (see Example 2 overleaf).

Example 1

Robert Atherton sells quantities of paper cleaning cloths. He buys them in large rolls, cuts them and distributes them as duster-size (12 to each packet). He has worked out the direct cost of each packet of 12 as £1 and sells them for £2.60. Thus, gross profit on each packet of 12 is £1.60. His overheads are £12,000 in the year, £1,000 a month. His break-even sales of packets of 12 cloths each month are:

Example 2

Jane Edwards runs a web design company. Each web site depends on the customer’s requirements and the cheapest is likely to be £10,000. For her business plan for the next 12 months, Jane has worked out the number of web sites she is likely to design. For the year, sales are estimated at £300,000 and the direct costs, that is, hardware, software and so on, are forecast to be £120,000.

Gross profit margin is:

The overheads of the business are estimated at £108,000 for the next year, that is, £9,000 a month.

The break-even level of sales for each month is:

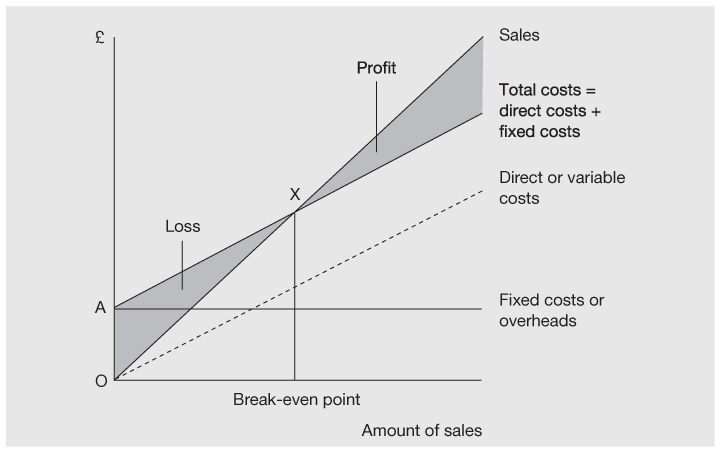

Figures 24.1 and 24.2 may help you to gain a better understanding of break-even. The level line shows the estimated level of overheads. The dotted line that starts at point O shows the amount of the direct costs for each level of sales. Total costs (line starts at A) are the sum of the direct costs and the overheads.

Figure 24.2 How an increase in fixed costs moves the break-even point upwards

The continuous sloping line starting at O shows the value of sales at different levels of units sold. X is the break-even point. To the left of X, your business is making a loss; to the right, your business is making a profit.

Figure 24.1 assumes that the level of overheads stays the same no matter what the level of sales you can make. Frankly, this is difficult to achieve in practice. Once you start doing more business, you may well find that your overheads will go up too. For example, you may find you need more admin support, given the increased amount of sales you are making. In Figure 24.2, you can see the effect on break-even point if there is an increase in overheads for the same business as below. Point X is now further to the right in Figure 24.2 compared with Figure 24.1. The break-even sales figure is now higher.

The plan to control the business

When you produced your business plan before you started your business (p. 49), you incorporated some forecasts: profit and loss and cash flow. These could form the basis for your plan (or budget) that you need to control the business, although probably with some adjustments.

What you need for a budget that you use to control your business, but that is also to give you (and any employees) something to aim for, is a plan incorporating figures that you believe you may be able to achieve.

As you are going to use the budget to control the business, you need to have the next year’s budget prepared before the previous year has ended, otherwise there is a time gap in which the business will drift. If you employ others in the business, they should be involved in drawing up the forecasts for their particular area of the business.

How to use the budget

Every month, as soon as possible after the end of it and not later than a fortnight after, you should have the actual profit, cost and cash figures to compare with the budget. Your comparison should be for two reasons:

- To identify what has gone wrong, and right, and to derive lessons for the future.

- To identify problem areas for the future, which may emerge only as your actual performance fails to keep up with budgeted performance.

Keeping in touch with the business

Once you start employing others, you will no longer be dealing with every single aspect of the business yourself. Once others have areas of responsibility, you will need to devise a system of management reporting. There is no one system that is perfect for a particular business, but it should include some of the following elements:

- Weekly reports: these could be verbal, for example a meeting. They need to be sufficiently detailed so that everyone in the business knows as a result their objectives for the next week and what is on the critical path to allow sales to be made and products to be purchased or made ready for sale.

- Monthly reports: these should be written by the person responsible, for example salesperson, manager or production staff. They should cover two aspects. First, what has been achieved over the past month, how it compares with budgeted figures and the objectives set in the weekly reports plus any explanations or lessons to be drawn from successes and failures. Second, the reports should consider the outlook for the next month, what should be achieved and what the objectives are.

While management reports allow you to keep informed about the business, they have an important side-effect. They force your employees to concentrate on the objectives of the business, their own performance against budgeted performance, and their own priorities for action in the weeks and months ahead.

Cash

If your cash runs out, your business will fail. It is as simple as that. Your cash can run out for several possible reasons:

- you do not sell enough;

- your costs are too high for the sales you make;

- you do not have enough cash to fund the increased number of debtors and stock quantities that extra business brings;

- you fail to collect the debts you are owed.

The cash budget

Preparing your business plan (p. 49) will have taken you some way towards knowing how much cash you will need in the business; indeed, the most important purpose of preparing the business plan may have been to raise the cash your forecasts show will be required. Once the business is trading, the cash flow forecasts need to be turned into monthly cash flow budgets.

You can help to conserve cash by paying by instalments as much as possible. For example, consider leasing cars or furniture rather than buying outright (p. 292).

Your aim should be not just to match your budget but to do better than it says. Never despise a penny or a pound that can be saved; very small savings build up over time into very large savings. This penny-pinching attitude applies just as strongly if you have raised money.

Comparing the actual cash performance with the cash budget is an important tool in controlling your cash. It enables you to learn from mistakes and plan your cash requirements in the future.

What else controls cash?

When cash is tight, you will take much more stringent measures than when you are cash-rich. For example, you could consider instituting the following control system:

- daily cash balance;

- weekly or daily bank statement;

- weekly forecast of each individual cash payment in (from customers) and planned cash payment out (to suppliers). This could be set up as a sheet with each named customer and supplier. Each day check what money you have received and tick off on your forecast sheet. Do not pay any cheques until you have received the money you need.

Obviously, when cash is short, you need to put your cash receipts in the bank as quickly as possible; and slow down the rate at which you pay your suppliers, though it is important to keep them informed.

Clearly, the system does not work for every business; it is a good control tool for businesses that have a smallish number of large receipts and payments. A retail business would not be able to operate in this way. However, a control sheet for a shop could consist of a weekly forecast of daily takings plus a list of those suppliers you intend to pay that week. Again, the suppliers will not be paid until the forecast cash comes in. Chapter 26, ‘Not waving but drowning’, looks at what happens when things are out of control (p. 357).

A cash system like this is a nuisance to operate, so if cash is not particularly short, you could use a variant of:

- weekly cash balance;

- weekly bank statement;

- monthly payment cycle, that is, set aside one day in each month on which you pay the bills you plan for that month. This means that there is only one day in each month devoted to writing cheques or authorising payments. If a bill is not paid on that day, it does not get paid until a month later.

Important note: no cash control system can operate if you do not keep proper cash records. This is explained in Chapter 27, ‘Keeping the record straight’ (p. 363).

Making cash work for you

Your problem may not be shortage of cash; on the contrary, you may have extra cash sitting around. In this case, do not leave it all in the current account. Instead, have sufficient handy to keep the business ticking over and put what you can in a seven-day-notice or call account that earns interest. Remember to give the required notice so that you can transfer what you need to cover your payments in your once-a-month cheque cycle.

Operating your bank account

Most banks have readily available leaflets detailing the charges on your business bank account. If your bank doesn’t, ask for the information, so you can work out in advance how much your bank charges are likely to be. Some banks will now tell you in advance what your next month’s charges will be based on the current month’s account usage. Most banks now make a standard charge for main account services, such as cheques, standing orders, direct debits and cash machine withdrawals. Charges may be lower for Internet banking. One way to economise is to use a credit or charge card for business expenses, as this is paid with a single payment, instead of lots of little ones.

However, it needs careful consideration before a card is given to an employee. Additionally, in the case of companies, use of a credit or charge card is a fringe benefit for employees, which would include you as a director; check how it would affect your individual tax bill.

If your business is on a very small scale, you should consider whether it is possible to run it using a building society account, rather than a bank account, bearing in mind there are limitations, such as no overdraft facility or business advice.

Some banks offer free banking for the first year (or even longer) if a small business opens an account. This can mean with some banks that there are no bank charges even if you have an overdraft.

Going into overdraft

It is becoming harder and harder to get an overdraft from a bank and the time to ask for one (p. 306) is not the day you realise that you will not be able to cover the bills of suppliers who are really pressing you for payment. The bank manager simply will not like it. It is much better for you to present a well-argued case one or two months before you think you will need the facility. This means planning ahead, by using your forecasts or budgets as a proper control tool.

Your customers

Selling is not the end of the story. Any old customer will not do. Making a sale to someone who does not pay their bill is worse than no sale at all. The ideal customer is one who pays their bill as soon as your product or service is handed over. Very few businesses are lucky enough to have that type of client. But there are steps you can take to try to ensure that you do get the cash in. First, you can check them out before you hand over the goods to them. Second, you can do everything you can to make them pay up as quickly as possible.

Giving credit to customers, that is, allowing them to become debtors and pay some time after they have received your service or product, costs you money. For example, if a bank charges 5 per cent on an overdraft, an outstanding bill of £1,000 costs you £50 if it is still unpaid after one year. Or, if it is unpaid after three months, the cost to you is £12.50. The more efficient you are at reducing the amount of time before you receive your payments, the lower the costs.

Investigating potential customers (credit control)

Few businesses can confine their sales to completely ‘safe’ customers who are guaranteed to pay what they owe and on time; usually, an element of risk is needed to meet your business objectives. But the riskiness or otherwise of customers needs to be assessed so that the risk is known and calculated. Assessment needs information, control and monitoring.

The extent of the investigation must also depend on the amount of the projected sale relative to your total sales. If it is a fairly small sale, the investigation alone may cost as much as the profit from the sale; you should establish a policy of rejecting or accepting such risks as a matter of course. But if the sale would be a significant order for you, further information is needed.

Consider the following steps:

- If you are dealing with a large quoted company, check its payment policy. This must be published in its annual report and accounts. Small businesses can by law claim interest for late payments from large businesses and public-sector bodies. However, surveys suggest that small businesses seldom use this right, possibly because they cannot afford to lose future business from a client as a result of a payment dispute. To find out more about your right to charge interest and the amount you can charge, see the Better Payment Practice Campaign* (at https://payontime.co.uk).

- Ask the prospective customer for a bank reference (but this will be based only on the bank’s experience, so it may indicate relatively little, but it will help in building a general picture).

- Ask for a couple of trade references. Put a specific question such as ‘Up to what level of trade credit is the customer considered a good risk?’.

- Ask a credit reference agency for a report about this prospective customer. There are three main agencies in the UK (Call Credit*, Equifax* and Experian*), and they keep records of how individuals and businesses manage their existing and past debts.

- Ask the customer for the latest report and accounts or a balance sheet and profit and loss account. Ask your accountant to analyse them for you.

- If you have not already done so, visit the business with a view to meeting the principals or directors. Put any questions that remain unanswered and use this visit to fill in the general picture.

Using the information you have garnered from all these sources, assess how risky you think this customer is and establish a credit limit. A common system is to have five categories of risk, ranging from the top category, who would be considered good for anything, to the bottom category, who you would sell to only on cash terms. You would draw up certain credit limits to apply to each category, for example allowed £1,000 on 30 days’ credit. The actual amounts would depend on the size of debts relative to your sales and what is considered normal practice in that industry.

The payment terms you offer (credit terms)

There is a range of possible credit terms you could offer customers. These include:

- cash with order (CWO);

- cash on delivery (COD);

- payment seven days after delivery (net seven);

- payment for goods supplied in one week by a certain day in the next week (weekly credit);

- payment for goods supplied in one month by a certain day in the next month (monthly credit);

- payment due 30 days after delivery (30 days’ credit).

You have to choose the best terms you can. This means that you extend credit for as short a time as possible, but obviously industry and competitive practice may to some extent put you in a straitjacket.

To encourage early payment of your bills, you can offer a cash discount for early payment; for example, payment within seven days of the invoice means the customer can claim a discount of 1 per cent. The problem with this sort of discount is that customers tend to take it (and, if your debtor control is a little sloppy, are allowed the discount) whenever they pay.

Sending out invoices

Be very prompt in sending out invoices. This is crucial to any policy of keeping tight credit control. Failure to do this will give the impression to debtors that you do not mind how long you wait for your money and, as we have seen, giving credit costs you money. No matter how busy you are keeping up with the work you do, sending out invoices, as soon as goods are delivered or services supplied, must take precedence.

The records you need for control

There is more detail on how to set up the records you need in Chapter 27, ‘Keeping the record straight’ (p. 363), but the records need to provide you with the following information:

- how much you are owed in total at any time;

- how long you have been owed the money and by whom; this information is known as an aged analysis of debts;

- a record of sales and payments including the date made for each customer. This allows you to build up your own picture of the credit-worthiness of individual debtors.

How to chase money you are owed

- Make sure your credit terms are known to your customer. The best way is to print them clearly on the invoice.

- As soon as your customer has overstepped the mark and the bill is overdue, ask for the money you are owed. This should be done politely in writing, preferably by e-mail or fax, with a follow-up in the post.

- If there is no reply within seven days, check that the details of the invoice are correct and that you have quoted all the information the customer needs to identify it, for example the customer’s own reference.

- E-mail or fax again. Follow up with a letter sent by recorded delivery.

- No reply within seven days? Make a telephone call to find out what the problem is. Do not assume that the customer has no money; there may be queries on the account or other problems. Find out the apparent reason for the non-payment.

- Use the telephone call to find out if the customer has a weekly or monthly payment run (p. 331) and find out the day this is done.

- Still no payment? Keep ringing and especially two or three days before the payment run. Try to extract a promise of payment.

- Keep the pressure up. Do not pester and then drop for a few weeks; all your previous chasing is undone. Keep up a steady and persistent guerrilla warfare.

- If the customer is always out or in a meeting when you telephone, and you suspect this is due to a desire not to speak to you, try pretending to be someone else who you are sure your customer will want to speak to. If you deal with an accountant or book-keeper, try speaking to the managing director of the customer’s business.

- Try different times of the day and the week: lunchtime is not usually a good time, but first thing Monday morning can be effective.

- When you eventually manage to speak to the person you want, if he or she says ‘I’ll chase it up and see what has happened’, say you will keep holding until they do.

- If the customer says ‘The cheque has been posted’, ask for the date this was done, whether it went first- or second-class, how much the cheque was for and what the cheque number is. Similarly, ask for the date the payment was authorised if it is being paid by automatic transfer. Transfers may take three working days to reach your account, but can be almost instantaneous if covered by the faster payments service. However, coverage of the faster payments service, which is limited to telephone and Internet transactions and standing orders, is patchy. You can check which types of payments and up to what amount are covered by each bank by going to www.fasterpayments.org.uk

- If the payment or cheque does not arrive, go to collect the money in person; this is what HMRC does. If paid by cheque, get the cheque cashed as soon as possible, so that it cannot be stopped.

- Check all the details of any cheque: your name, the amount, the date, the signature.

- If all the previous steps have failed, send a formal letter, preferably from your solicitor, either threatening to take legal action to recover the debt or to start bankruptcy or winding-up proceedings (p. 358) or threatening to use a debt-collection agency. Keep to the threat.

- Consider using an agency (see below).

- Consider issuing a writ for the debt or consider starting bankruptcy proceedings against an individual or winding-up proceedings against a company. Consider using the small claims court. Ask your solicitor’s advice.

Using a debt collection agency

Once the money has been overdue for two to three months, you could hand collection over to an agency. They will write and phone and eventually either collect the money, or report that it will only be collected by legal action. The usual charge for an agency is some percentage of the money recovered.

A halfway house to using the full-blown debt collection service is to use an agency to write to overdue customers pointing out that non-payment will be reported to credit reference agencies, which may harm the customer’s credit rating. As this is very important to a business, it often has the desired effect. However, payment is made to you not the debt collection agency and, so long as this is done, no entry is made on the customer’s file at the credit reference agencies.

Selling your debts to raise cash (factoring)

Essentially, a factor buys your debts in return for an immediate cash payment. Generally speaking, factoring is available for debts from other businesses, rather than individuals. In a full service, the factor takes over your records for debtors and collects the debts. In return, you could receive a payment of up to 80 per cent of the face value of the invoices. The balance of the money will be paid when the debts are collected. Factoring occurs on a continuing basis, not for one individual set of debtors. The factor will often offer insurance against bad debts. There are also less complete services, for example:

- the factor does not take over your records;

- the customer does not pay the factor but pays you;

- invoice discounting, that is, you maintain the records and collect the debts. This means that your use of the service remains confidential and your customers are not aware of it.

While a factoring service seems to be the answer to your cash flow dreams, there are some conditions:

- if your sales are less than £100,000 a year, you may find it difficult to factor your debtors;

- the factor will investigate your trading record, bad debt history, credit rating procedure, customers and so on before deciding whether to offer you a factoring service;

- some factors give automatic protection against bad debts; others do not;

- you are likely to have to agree to a one year’s contract with a lengthy period of notice.

Note that all the separate components of factoring, that is, keeping your debtor records, cash collection, invoice discounting and credit insurance, are available separately from a number of organisations. Compare costs of several factoring services and look at the cost of the individual components.

Your suppliers

Quite a lot of the way you can deal with your suppliers (or creditors when you owe them money) is simply the reverse of what you do with debtors. Taking credit from suppliers is a significant source of finance for most small businesses. However, the other side of the coin is that those suppliers may be short of funds themselves and heavily dependent on getting in the money they are owed as quickly as possible.

When you are short of cash, you may find yourself chasing your customers and cursing them for not paying up while doing exactly the same yourself to other businesses. As a starting point, your first step should be to try to negotiate improved credit terms from your suppliers rather than simply taking unapproved extended credit.

Unfortunately, being open with your suppliers does not always pay off. Saying that you are short of cash this week but you will pay next week can cause panic. Your creditor may issue a writ without delay, and your future credit terms may be affected.

Nevertheless, when the chips are down, one way of seeing yourself through a temporary shortage of cash is to push up the length of time you take to pay your creditors. However, it is a slippery road; what you fervently believe to be a temporary shortage of cash may turn into a permanent shortfall. If you cannot make good the shortfall by raising more permanent funds, you will go to the wall with a lot of unpaid bills. A lot of small businesses like yours will also lose money as a result of your action. Somehow, you have to know where to draw the line (p. 357).

What happens when a supplier investigates you?

Any well-organised supplier will carry out the same screening of you as you do of customers who are going to place largish orders with you. Expect to be asked for:

- permission to approach your bank for a reference;

- two trade references;

- a balance sheet or a set of the latest accounts;

- further information as a result of the supplier’s investigation.

The supplier will also probably approach a credit reference agency to see what it has on you and what your credit rating is. However, when you are starting in business, you can provide none of the information mentioned above. You may be forced to pay in cash initially, until you have built up some sort of record. A large supplier may even ask for a personal guarantee. You may be able to avoid this if you can demonstrate that you have sufficient funds raised to get the business through the building-up stage.

The records you need for control

Details of the records you should set up are given in Chapter 27, ‘Keeping the record straight’ (p. 363). But you should be able to derive the following information from them:

- how much you owe in total at any time;

- how long you have owed the money and to whom;

- a record of what you have paid each supplier and when.

How to delay paying what you owe

Essentially, you can use only a series of excuses, not to say downright lies; there are few honest ways of delaying payment. However, it may be some comfort to know that most successful small businesses at some stage have to delay payment.

The first step to take is not to consider paying any bills until you are asked to.

The second step is to introduce a paying schedule that involves making cheques out only once a month.

Further steps involve simply delaying paying. The sorts of excuse are those mirrored in ‘How to chase money you are owed’ earlier in this chapter (p. 335).

Summary

- The first stage for any new business is to get to the break-even point; after that, building up profits is needed for long-term survival.

- Watch out for overheads; they have a nasty knack of rising with sales, thus continually pushing up the break-even point.

- Convert your business plan and forecasts into a budget that gives you, and your employees, something to aim for.

- Keep control of your business by comparing actual with budget performance; try to draw the appropriate lessons to be learned and plot ahead any changes in your plan that are needed.

- If you have employees, introduce a system of weekly and monthly reporting and setting of objectives.

- Controlling cash can keep your business afloat until break-even is reached.

- Make your cash work for you; that is, if you have spare funds put them in an interest-earning account.

- Operate your bank account as efficiently as possible.

- Try to speed up the rate at which your sales are turned into cash. Do this by exercising credit control and investigating potential customers, offering the tightest credit terms you can, sending out invoices promptly and chasing overdue bills. Use ‘How to chase money you are owed’ on p. 335.

- Most successful small businesses have to stoop to delaying payment to their suppliers at some time during their development.