2

The Advertising Bubble

Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is, I don’t know which half.

—John Wanamaker1

Advertisements are now so numerous that they are very negligently perused, and it is therefore become necessary to gain attention by magnificence of promises, and by eloquence sometimes sublime and sometimes pathetic.

—Samuel Johnson2

Good journalists respect what they call the “Chinese wall.” That’s the virtual partition between what they do and what their business sells. For the most part, the latter is advertising. Journalists don’t want their interests conflicted, so they stay disinterested in the advertising side of the business.

There is a similar wall in the minds of advertising people, separating their inner John Wanamaker from their inner Samuel Johnson. On one side, they do their best to make good advertising. On the other side, they join the rest of us, drowning in a flood of it. Like journalists, advertising folk are aware of what’s happening on the other side of the wall. Unlike journalists, it’s not in their interest to ignore it.

Nobody is in a better position to understand what’s happening on both sides of both walls than Randall Rothenberg. For three decades, he’s worked as an author and journalist, covering marketing and advertising for Bloomberg, Wired, Esquire, Advertising Age, the New York Times, and other publications. For most of the time since 2007, he has been president and CEO of the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB). Here’s how he explains the role of advertising’s Chinese wall:

There are two discrete conversations taking place in our realm that simply don’t ever intersect. One conversation posits that the future of marketing will be based entirely on the reduction of all human interactions and interests into sets of data points that can be analyzed and traded. The other conversation posits that marketing success derives entirely from content, context, environment and the qualitative engagement of human emotion.3

Both conversations are professional factions, and both have their own approaches to the separate problems of Wanamaker and Johnson. The quantitative faction works on ways to make advertising as personalized and efficient as possible, with or without voluntary input from the persons targeted. The emotional faction works to improve advertising by changing its mission from targeting to engagement.

I think the emotional faction has the edge, because engagement is the only evolutionary path out of the pure-guesswork game that advertising has been for the duration. It’s what will survive of advertising when the Intention Economy emerges. In the short run, however, the quantitative faction is driving growth in the Attention Economy, and the flood of advertising output continues to rise. In June 2011, eMarketer estimated that the annual sum spent on advertising would exceed half a trillion dollars in 2012 and pass $.6 trillion in 2016.4 Four months later, eMarketer moved the dates closer by one year apiece.5

These numbers measure tolerance more than effects.

Tolerance

No medium has tested human tolerance of advertising more aggressively than television, which has long been the fattest wedge in advertising’s pie chart of spending6 (40.4 percent of the projected total worldwide in 2012, according to Zenith Optimedia;7 and around 72 percent in the United States, according to Nielsen and AdCross).8 So let’s dive into TV for a bit. How much advertising do we tolerate there? And how much less will we tolerate after we do all our TV watching on devices that are not designed and controlled by the TV industry?

In the United States, the typical hour-long American TV drama runs forty-two minutes. The remaining eighteen minutes are for advertising. Half-hour shows are twenty-one minutes long, with nine left for advertising. That’s 30 percent in each case. The European Union sets a limit of twelve minutes per hour for advertising on TV, which comes to 20 percent. Ireland holds broadcasters to ten minutes per hour, or 16.7 percent. Russia by law sets aside nineteen minutes per hour for advertising: four for “federal” messages and the rest for “regional” ones. Russia is also considering lowering those numbers, due to a decline in viewing.9 Thus, eighteen minutes seems to be the upper limit.

So far, nobody is pushing that limit online, except with simulcasts. On the Web, Hulu sells only two minutes of advertising per half hour.10 Commercial podcasts and streaming videos tend to have only “bumper” ads at the front and back. As viewing and listening migrate from TV and radio to the Net, however, it’s only natural for producers to look for ways to increase revenues by loading more advertising into content. To help with that, comScore in 2010 released a research report titled, “Great Expectations: How Advertising for Original Scripted TV Programming Works Online.”11 From the introduction:

Eager to sustain growth online both in audience size and time spent viewing long format TV content, publishers have erred on the side of fewer ads against a typical TV program. However, although audiences continue to grow in both size and engagement, this approach has resulted in challengingly low ratios of ads to content—typically, 6–8% of viewing time is ads against most long format TV programs viewed online, compared to 25% on television. Consequently, the business model around online distribution of TV programs is becoming difficult to sustain for many content providers.12

Note the perspective here. Publishers “have erred” by running fewer ads. To comScore, the problem is not enough advertising. So it surveyed to see how large an advertising load the audience will bear when viewing scripted TV on devices other than TVs. Not surprisingly, it found “cross-platform viewers” (ones that watched TV online as well as the old-fashioned way) were much more positive toward advertising than were TV-only viewers, that “43% of all cross platform viewers stopped watching a TV program online in order to visit an advertiser’s website,” and that “over 25% of the audience who were reached by online video advertising felt that the commercials were enjoyable.”13

Thanks to advertising’s Chinese wall, the reciprocal numbers don’t get mentioned. Here, they are: 57 percent didn’t stop to visit a promoted Web site, and 75 percent did not find commercials enjoyable.

ComScore also did a “sensitivity meter analysis” to find “ad load tolerance levels.” It surveyed 640 people and spread the results across a graph titled “Desired Length of Commercials Online: 18–49.” ComScore came to the conclusion that around six minutes was most “desirable,” because 50 percent or more of those surveyed considered six minutes to be either “long enough” or “too long.”14

Now, if you’re not in the advertising business, you might ask, Is advertising something viewers desire at all? In fact, comScore’s findings show that nearly all people find some level of advertising intolerable. Asking how much of an ad load people will bear is like asking how much brown matter they can stand in their water, or how many extra pounds of fat they’re willing to carry.

If advertisers would peek over on our side of the Chinese wall, they would see two icebergs toward which TV’s Titanic is headed, and both promise less tolerance for advertising. One is demographics and the other is choice.

The Ageberg

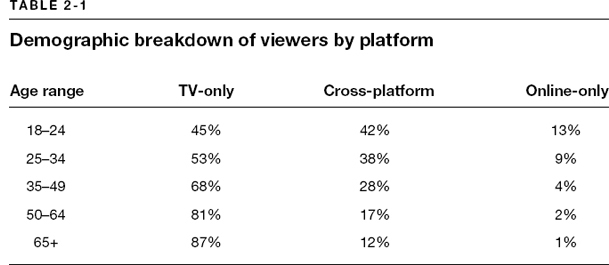

We can see the demographic iceberg approaching in the comScore’s breakdown, in the same study, for five demographics (see table 2-1).15

Already, the majority ages eighteen to twenty-four watch TV on devices other than TVs, and TV-only as a platform is going down while online-only is going up. At some point, it will become clear that TV is a video format and not a platform, and that the only platform still worthy of the noun is the Internet.

The Choiceberg

The tip of the choice iceberg is TiVo, which has been around for more than a decade. TiVo was the first digital video recorder (DVR, aka PVR). It gave users a way to store TV shows as files and to skip over ads when viewing shows later. The full implications of TiVo still haven’t fully sunk in, although there are plenty of people in The Industry (as they call it in L.A.) who saw the end coming from the start. One is Jonathan Taplin, a veteran Hollywood producer, writer, entrepreneur, and currently a professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism.16 At the Digital Hollywood conference in September 2002, Taplin was on a panel during which the moderator asked the audience to raise their hands if they had a TiVo.17 Nearly every hand went up. Then he asked them to drop their hands if they didn’t use their TiVo to skip over ads. The hands stayed up. “There goes your business model,” Taplin said.18

Six years later, in 2008, engadget published a press release by the management consulting firm Oliver Wyman reporting that 85 percent of those surveyed by the company used their DVR to skip at least three-quarters of all commercials. Those surveyed also said they would not want to “watch advertising even when it underwrites free content.” Nor would they pay extra to remove ads.19

These findings were published in the Oliver Wyman Journal, in a long report by John Senior and Rafael Asensio, titled “TV 2013: Is It All Over?”20 In it, they look at two scenarios they call “Non-TV” and “Next TV.” With Non-TV, video is just video. Watch it on anything: your flat screen, your laptop, your phone, your tablet, or any other device you like. Today’s TV content sources go direct, and sell or give you whatever you like. With Next TV, the cable and satellite systems continue couch potato farming the old-fashioned way, but with better Internet integration.

Non-TV is what the cable industry calls “over the top.” It’s a good metaphor, since the bottom is its whole old system, and it’s a dam that’s breaking down. What’s spilling over it isn’t a brook or a river anymore. It’s an ocean of video files and streams from millions of sources, most of which are already available à la carte through YouTube and other online distributors. So far, most “original scripted programming” is still confined to old-fashioned TV, but in time, that stuff will move online as well. Consider the choice. With TV, your choices are sphinctered through a set-top box. With the Internet, you can watch on whatever device you like. It’s no contest.

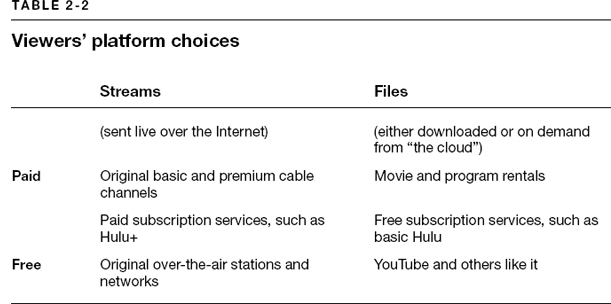

Meanwhile, we’re willing to put up with what’s left of TV, for two reasons: (1) because it’s still normative, and (2) because the stuff we want most is still trapped inside TNT, ESPN, HBO, and other cable-only networks. But how long will those networks put up with being stuck inside an old system that’s breaking down? They’ll bolt for the Net as soon as they’re sure they will still get paid for their goods. Once that’s worked out, your choices as a viewer will be simple: you’ll watch some mix of live streams and stored files, some of which you’ll pay for and some of which you won’t. Table 2-2 shows a possible sorting out.

How it all sorts out matters less than the fact that all of it will be “over the top” on the Internet.

More of Less

When TV’s sources go direct through the Internet, what happens to advertising? The old TV system was built to make you watch advertising, while the Internet is built to let you do whatever you like. Yes, there are ways you can be forced to watch ads on cable-over-Internet services such as Hulu and Xfinity. But we still have the “load” tolerance problem that comScore probes. We’ll put up with some advertising, but far less than we did in captivity. If the most we’ll tolerate is six minutes per hour, as comScore says, that’s a two-thirds drop from what you got over the old tube. You might put up with eighteen minutes per hour on a live sportscast, no matter what glowing rectangle you watch it on. But will you put up with it on everything else? Doubtful.

After reading the comScore study, Terry Heaton, one of the top consultants in the TV industry, posted an essay titled, “Media’s Real Doomsday Scenario.” An excerpt:

The advertising hegemony used by Madison Avenue is about to collapse, and when it goes, it will take traditional media with it. As alarming and preposterous as that might seem, it is exactly the impossibility of such a situation that makes it so likely and so dangerous. When it happens, those involved will look around in astonishment and insist that it couldn’t have happened and that, indeed, either advertisers or media moguls have lost their minds.21

Heaton isn’t alone. Bob Garfield, author of The Chaos Scenario, cohost of NPR’s On the Media, and veteran columnist for Ad Age, shook the walls of the advertising world in March 2009 with an Ad Age column titled, “Future May Be Brighter, but It’s Apocalypse Now.” He writes,

Chicken Little, don your hardhat. Nudged by recession, doom has arrived. The toll will be so vast—and the institutions of media and marketing are so central to our economy, our culture, our democracy and our very selves—that it’s easy to fantasize about some miraculous preserver of “reach” dangling just out of reach. We need “mass,” so mass, therefore, must survive. Alas, economies are unsentimental and denial unproductive. The post-advertising age is under way.22

The Greater Unknown

So why is advertising’s apocalypse running late? One reason is that the TV programs viewers like best (especially sports) are still trapped on cable, and cable isn’t giving up easily. (Even the live streaming of HBO GO requires a cable or satellite subscription.) The other is that online advertising is growing rapidly, thanks partly to a growth in the number of places where ads can be placed and partly to innovations in tracking, targeting, and personalization. This is the quantitative conversation Randall Rothenberg talked about, and it has become a craze.

The Wall Street Journal began following this craze in the summer of 2010, when it launched an investigative series titled, “What They Know.”23 The first article, which ran on July 30, 2010, said,

One of the fastest-growing businesses on the Internet … is the business of spying on Internet users. The Journal conducted a comprehensive study that assesses and analyzes the broad array of cookies and other surveillance technology that companies are deploying on Internet users. It reveals that the tracking of consumers has grown both far more pervasive and far more intrusive than is realized by all but a handful of people in the vanguard of the industry.24

Over the following months, the Journal’s series grew to dozens of reports, polls, and graphical illustrations. The findings were many. Here are a few, in summary form:

- Data gathering is a new and lightly regulated industry based on surveillance, harvesting, and selling data and data-educated guesses about what users might want, in real time.25

- All the largest commercial Web sites in the United States put intrusive tracking devices in computers visiting their sites. Some installed more than a hundred of these things in a single visit. Forty-nine of the fifty most popular Web sites installed a total of 3,180 tracking files on the Journal’s test computer. Twelve (including IAC/InterActive Corp.’s Dictionary.com, Comcast Corp.’s Comcast.net, and Microsoft’s MSN.com) had each installed more than a hundred files.

- It’s worse for kids. The top fifty sites targeting teens and children installed 4,123 tracking files on the Journal’s test computer: 30 percent more than for sites targeted at adults.26

- In response to the poll question, “How concerned are you about advertisers and companies tracking your behavior across the Web?” 85 percent of respondents were “very alarmed” or “somewhat concerned.”27

- In the back-end market for buying and selling personal data in real time, the biggest player is BlueKai, which “trades data on more than 200 million Internet users, boasting the ability to reach more than 80% of the U.S. Internet population.”28

- Most users had few if any clues that they were being tracked. Case in point: many phone apps share the customer’s user name, password, location, contacts, age, gender, location, unique phone ID (equivalent of a serial number), and phone number with third parties, which in turn represent countless advertisers.29

- The biggest exposure comes not from location-oriented apps like Foursquare, but from apps that do not appear to be location-based, or even advertising-supported—and quietly make money by selling users’ location data to advertisers, without users’ knowledge or permission. One app tested by the Journal sent personal data to eight different ad networks.30

- There is a big business in building detailed information about people, gleaned from tracked browsing and digital crumb trails. Writes the Journal,

firms like [x+1] [sic] tap into vast databases of people’s online behavior—mainly gathered surreptitiously by tracking technologies that have become ubiquitous on websites across the Internet. They don’t have people’s names, but cross-reference that data with records of home ownership, family income, marital status and favorite restaurants, among other things. Then, using statistical analysis, they start to make assumptions about the proclivities of individual Web surfers. “We never don’t know anything about someone,” says John Nardone, [x+1]’s chief executive.31

- Companies such as Kindsight and Phorm do “deep packet inspection”—the same technology used by spy agencies for surveillance of terrorism suspects—to “give advertisers the ability to show ads to people based on extremely detailed profiles of their Internet activity.”32

- “Scraping”—copying every message an individual posts, even on private sites—is another popular way for advertisers to gather information about individuals. The Journal found a number of companies that live to “harvest online conversations and collect personal details from social-networking sites, résumé sites and online forums where people might discuss their lives.”33

- Answering the poll question, “Would you use an Internet ‘do-not-track’ tool if it were included in your Web browser?” more than 92 percent said yes.34

Not surprisingly, on December 1, 2010, the Federal Trade Commission issued recommendations for a “do not track” mechanism on browsers.35

Picking up on the FTC’s cue, USA Today and Gallup conducted a poll of a random-dialed sample of 1,019 adults over eighteen years old on December 11–12, 2010.36 To the question, “Should advertisers be allowed to match ads to your specific interests based on Web sites you have visited?” 67 percent said no. And, while 30 percent agreed with the statement, “Yes, advertisers should be allowed to match ads to interests based on websites visited,” and 35 percent also agreed with, “Yes, the invasion of privacy involved is worth it to allow people free access to websites,” the reciprocal numbers—70 percent and 65 percent—show negative demand by its recipients for tracking and advertising personalization.

At some point, The Market—meaning people gagging on advertising—will pull their invisible hands out of their pockets and strangle the source.

Waste

One might think all this personalized advertising must be pretty good, or it wouldn’t be such a hot new business category. But that’s only if one ignores the bubbly nature of the craze or the negative demand on the receiving end for most of advertising’s goods. In fact, the results of personalized advertising, so far, have been lousy for actual persons.

Chikita Research, a primary source for online advertising statistics, published a report in September 2010 with the headline, “Ad Layout Series: Above The Fold Ads Get 44% Higher CTR.”37 The fold is an old newspaper term and was meant literally. Full-size papers (non-tabloids, such as the New York Times) are folded, and in the caste system of newspaper advertising and editorial placement, “above the fold” is always better, no matter what the page. Online, “below the fold” refers to space outside the typical browser’s viewing area. Chikita found that CTRs both above and below the fold run at less than 1 percent (0.939 percent and 0.651 percent, which combined are 0.818 percent).

From advertising’s side of its Chinese wall, all this waste is okay, because advertising is guesswork, and online the waste is easier to ignore because it has been relocated: moved from airwaves, billboards, and newsprint to server farms, pixels, rods, and cones. But it’s still there. So are the costs, which far exceed zero.

Branding

Of course, that’s the view from our side of the Chinese wall. From the side where advertising comes from, most of that waste can be excused, because even its failures can be rationalized as “branding.” Within the industry—and even outside it (see the sidebar, “Nothing Personal”)—branding is a subject of countless books, articles, and postings on the Web. What was once an “image” is now a “promise,” an “experience,” and an “asset” that has “equity.”

It’s easy to forget that the term branding was borrowed from the cattle industry. The idea was to burn the name of a company or a product onto the brains of potential customers.

Procter & Gamble’s first brand was Ivory soap, in 1878. The product and its strategy were so successful over the following decades that brand management eventually became a serious business discipline.38 This happened in the 1930s, when America was getting hooked on radio, and women listening at home were entertained by soap operas, which were mostly sponsored by brands of cleaning products. It was in this era that grocery store chains also grew, and “shelf wars” were won by companies that maximized varieties of packaging and promises, while minimizing the actual differences between the products themselves. This is also when the first jingles came along. Hence the old industry adage, “If you’ve got nothing to say, sing it.”

Clogged Filters

In The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You, Eli Pariser writes,

“You have one identity,” Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg told journalist David Kirkpatrick for his book The Facebook Effect. “The days of having a different image for your work friends or coworkers and for the other people you may know are probably coming to an end pretty quickly … Having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity.”47

Later, Zuckerberg discounted the remark as “just a sentence I said,” but to Facebook, the only you that matters is the one it knows. Not the one you are.

In the closing sentences of The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to our Brains, Nicholas Carr writes,

In the world of 2001, people have become so machinelike that the most human character turns out to be a machine. That’s the essence of Kubrick’s dark prophecy: as we come to rely on computers to mediate our understanding of the world, it is our own intelligence that flattens into artificial intelligence.48

Even if our own intelligence is not yet artificialized, what’s feeding it surely is.

Pariser sums up the absurdity of it all in a subchapter titled, “A Bad Theory of You.” After explaining Google’s and Facebook’s very different approaches to personalized “experience” filtration and the assumptions behind both, he concludes, “Both are pretty poor representations of who we are, in part because there is no one set of data that describes who we are.” He says both companies have dumped us into what animators and robotics engineers call the uncanny valley: “the place where something is lifelike but not convincingly alive, and it gives people the creeps.”49

Lost Signals

The ideal of perfectly personalized advertising is also at odds with the nature of advertising at its most ideal. This ideal is perhaps best expressed by the most canonical of all ads for advertising: McGraw-Hill’s “The Man in the Chair.” Of it, David Ogilvy (the most respected—and certainly the most widely quoted—figure in the history of advertising) wrote, “This ad summarizes the case for corporate advertising.” It features a bald guy in a suit and bow tie, sitting in an office chair with his fingers folded, looking out at the reader. Beside him, in the white space of the ad, runs this copy:

“I don’t know who you are.

I don’t know your company.

I don’t know your company’s products.

I don’t know what your company stands for.

I don’t know your company’s record.

I don’t know your company’s reputation.

Now—what was it you wanted to sell me?”

MORAL: Sales start before your salesman calls—with business publication advertising.

In economic terms, what the man wants are signals, and those signals are not just about what’s for sale. In “Advertising as a Signal,” Richard E. Kihlstrom and Michael H. Riordan explain how advertising signals the substance of the company placing it:

When a firm signals by advertising, it demonstrates to consumers that its production costs and the demand for its product are such that advertising costs can be recovered. In order for advertising to be an effective signal, high-quality firms must be able to recover advertising costs while low-quality firms cannot.50

In “The Waste in Advertising is the Part that Works,” Tim Ambler and E. Ann Hollier compare advertising to the male peacock’s tail: a signal of worthiness that a strong company with a quality product can afford to display, but a weak company cannot.51

Therefore, placing an ad in a McGraw-Hill publication wasn’t just a branding effort or a briefing in advance of a sales call. It was a signal of financial sufficiency. But that ad ran back when Mad Men ruled the advertising world, and print publications conveyed the most substance. Today, the grandchildren of the man in the chair get their news from the Net. Thus, Don Marti, former Editor-in-Chief of Linux Journal, suggests one more item for the Man In The Chair’s list: “I don’t know if your company is really spending a lot on advertising, or if you’re just targeting me.” He explains,

Here’s the problem. As targeting for online advertising gets better and better, the man in the chair has less and less knowledge of how much the companies whose ads he sees are spending to reach him. He’s losing the signal … On the web, how do you tell a massive campaign from a well-targeted campaign? And if you can’t spot the “waste,” how do you pick out the signal?52

Perhaps the financial sufficiency signal doesn’t matter much in a time when advertising from a zillion unknown sources is the norm and companies come and go at the speed of fads. But if that’s the case, advertising itself might not matter much, either. In other words, advertising may now be giving away some of the soul it has left.

The true lodestar of advertising has always been the customer. This is why “the man in the chair” ad was so important. It was a signal sent by McGraw-Hill to advertisers on behalf of its readers. It spoke of the company’s relationship with those readers and said to advertisers that it stood on the readers’ side. It demanded substance, relevance, and earned reputation from its advertisers. It said relationships were possible, but only when customers sat with companies at the same table, at the same level.

Anonymity

Tracking and “personalizing”—the current frontier of online advertising—probe the limits of tolerance. While harvesting mountains of data about individuals and signaling nothing obvious about their methods, tracking and personalizing together ditch one of the few noble virtues to which advertising at its best aspires: respect for the prospect’s privacy and integrity, which has long included a default assumption of anonymity.

Ask any celebrity about the price of fame and he or she will tell you: it’s anonymity. This wouldn’t be a Faustian bargain (or a bargain at all) if anonymity did not have real worth. Tracking, filtering, and personalizing advertising all compromise our anonymity, even if no PII (personally identifiable information) is collected. Even if these systems don’t know us by name, their hands are still in our pants.

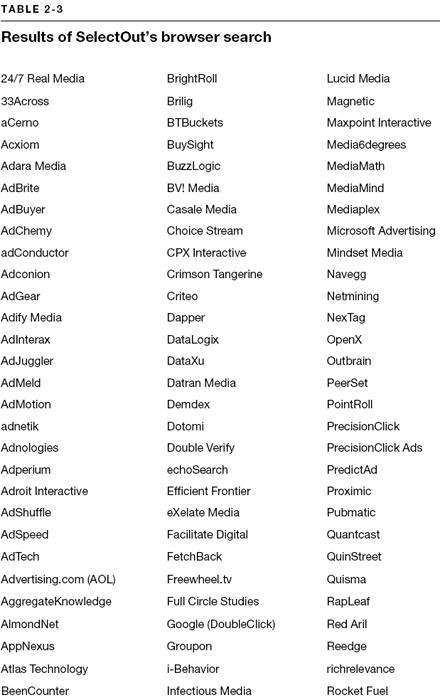

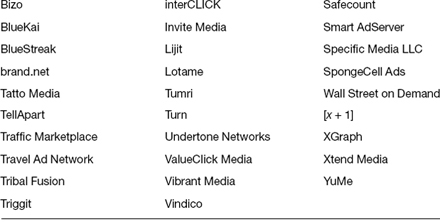

SelectOut.org is a “privacy manager” Web site that cleverly surfaces all the advertising companies with tracking hands inside your browser’s trousers. Table 2-3 shows a list of the company hands SelectOut just found inside one of my browsers.

If you’re not familiar with the companies listed in the table (and this is just a subset of the whole business), it helps to look at what they say about themselves. I’ll choose one at random: Reedge. This is from Reedge’s “Our Company” Web page:

Reedge offers online software that helps site operators to identify and track user behavior, optimize the site performance and serve customized pages to improve conversion and drive more transaction revenue. Reedge customers pay a monthly subscription fee and receive unlimited access to Reedge tools, software and professional support.

Reedge works by segmenting the audience based on their browser type, location and online behavior to identify their intent, then dynamically customizes the text, images, pop-up offers and other content to improve conversion and boost sales.53

And here’s what Rocket Fuel says on its “About” page:

Rocket Fuel goes beyond other audience targeting technologies by combining demographic, lifestyle, purchase intent and social data with its own suite of targeting algorithms, blended analytics and expert analysis to find active customers. Rocket Fuel uses its technology to deliver better ROI for premium brand marketers—whether their objectives are brand-oriented or designed to drive a conversion event.54

The italics are mine.

Note how both these companies assume that user intent is something the company needs to figure out. They are not alone in this. All the companies on the list in the table have the same ambition.

The distance between what tracking does and what users want, expect, and intend is so extreme that backlash is inevitable. The only question is how much it will damage a business that is vulnerable in the first place.

Terminal Delusions

Eric K. Clemons, professor of operations and information management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, visited those vulnerabilities in a March 2009 guest post on TechCrunch titled, “Why Advertising Is Failing On The Internet.”55 His post is long and detailed, but compressed to its essence, it says this:

- There must be something else. (There will be other business models.)

- We don’t trust advertising. (It’s among the least trusted forms of communication.)

- We don’t want to view advertising. (Given the option, we avoid it.)

- We don’t need advertising. (There are plenty of other ways to get information.)

TechCrunch readers didn’t like what Clemons wrote. Of the six hundred comments below the post, nearly all were negative. “WOW!” wrote one reader, “This is one of the most ignorant and misinformed articles I have ever read! First, Internet advertising is one of the most profitable, fastest growing industries in existence.”

Clemons replied,

I’ve been attacked and ridiculed before. I warned the floor traders in New York about the coming of online trading back in 1989 and was fired for it. I warned traditional people-based travel agents about dropping commissions and their eventual bypass through online booking systems and was ridiculed …

And even if you continue to ridicule my piece, there are too many other professionals noticing the same thing. Consider the recent article in the Economist56 on essentially the same thing: advertising cannot fully support the net. You cannot ridicule everything you do not like off the net.57

Yet we can’t ignore the huge numbers of people who live within or on the shores of the vast money river that flows through advertising, especially online. That’s where the ridicule comes from, and it won’t stop until the bubble pops.

Advertimania

The etymologist Douglas Harper calls mania “mental derangement characterized by excitement and delusion,” adding that it has been used in the “sense of ‘fad, craze’” since the 1680s, and since the 1500s “as the second element in compounds expressing particular types of madness (cf. nymphomania, 1775; kleptomania, 1830; megalomania, 1890).”58 I believe we have advertimania today.59 Here’s why:

- An overly generous infusion of liquidity, in the form of venture capital. This capital is invested both in companies that expect to make money through advertising, and in advertising for those companies and others. This was rampant in the dot-com boom and is again today.

- Faith in endless growth for advertising and in its boundless capacity to fund free services to users.

- Herd mentality—around advertising itself and in faith that ad-supported social media will persist and grow indefinitely.

- Huge increase in trading. This is happening with user data bought and sold in back-end markets, employing the same kind of “quants” who worked on Wall Street during the housing bubble.60

- Low quality of personal information, despite the claims of companies specializing in personalization.

And that’s just on advertising’s side of the Chinese wall. Over here on our side, we can add to that list (especially the last item) six delusions, inclusive of the ones listed by professor Clemons:

- We are always ready to buy something. We’re not. In fact, most of the time we’re not about to buy anything. Even if we don’t mind being exposed to advertising when we’re not buying, nearly all of us do mind being watched constantly—especially by parties whose main interest is in selling us stuff.

- People will welcome totally personalized advertising. Even if people allowed themselves to be tracked constantly through the world and to be understood in great detail (a privilege that advertisers have done little if anything to earn), the result would still be guesswork, which is the very nature of advertising. For customers, rough impersonal guesswork is tolerable, because they’re used to it. Totally personalized guesswork is not. At least not by advertising. To become totally personal, advertising needs to cross an existential bridge, to become a different corporate function. It must become sales—without the human sound or the human touch.

- The market for tracking-based advertising is large enough to justify the huge investments being made in it. Christopher Meyer, founder of Monitor Talent and frequent author on the impact of technology on markets (including Blur: The Speed of Change in the Connected Economy,61 coauthored with Stanley M. Davis) says, “It’s an eyeball bubble. Investments in tracking-based advertising assume impossibly high values for a customer’s attention. The incremental business just won’t be that big. And if eyeballs are overvalued, then advertising as a category should crash.”62

- Advertising is something people actually like or can be made to like. It’s not. With a few all-too-rare exceptions (such as Super Bowl ads, which are typical mostly of themselves), advertising is something people tolerate at best and loathe at worst. Improving a pain in the ass does not make it a kiss. Nor does putting a thumbs-up “like” button next to an ad that gets ignored 99.X percent of the time.

- The client-server structure of e-commerce will persist unchanged. It won’t. I’ll explain why in the next chapter, meanwhile, here’s Kynetx CEO Phil Windley: “There are a billion commercial sites on the Web, each with its own selling systems, its own cookies, its own way of dealing with customers, and its own pile of data about each customer. This whole architecture will collapse as soon as customers have their own systems for dealing with sellers, their own piles of data, and their own contexts for interaction.”63

- Companies have to advertise. In fact, advertising is not an essential function of any company. The difference between an advertiser and an ordinary company is zero. Even if we call advertising an investment, it’s on the expense side of the balance sheet and an easy item to cut.

Each of those delusions is a brick in the Chinese wall between the industry’s mentality and the larger marketplace outside it. You could call that wall a blind side, but it’s more than that. It’s a screen on which an industry that smokes its own exhaust has long been projecting its fantasies. It sees those projections rather than the real human beings on the other side. It also fails to see what those human beings might bring to the market’s table, beyond cash, credit cards, and coerced “loyalty.”

The Fix

Advertising may fund lots of stuff that we take for granted (such as Google’s search), but it flourishes in the absence of more efficient and direct demand-supply interactions. The Internet was built to facilitate exactly those kinds of interactions. This it has done since the mid-nineties, but only within a billion different silos, each with its own system for interacting with users, and each with its own asymmetrical power relationship between seller and buyer.64 This system is old, broken, and long overdue for a fix.

The Internet, meanwhile, has always been a symmetrical system. Its architecture, defined by its founding protocols (which we’ll visit in chapter 9) embodies end-to-end principles. Every end on the Net has equal status, whether that end is Amazon.com, the White House, your laptop, or your phone. This architectural fact is a background against which advertising’s asymmetries, and its delusional assumptions, have always stood in sharp relief.