14

Vertical and Horizontal

So then Apple is the ultimate unGoogle. Right? Not so fast.

—Jeff Jarvis1

The smartphone business was invented by Nokia and RIM around the turn of the millennium and then royally disrupted by Apple and Google a few years later. Today, Apple and Google define the smartphone business, together, though not always in direct competition. It is important to understand how this works, because the two companies’ directions are orthogonal: ninety degrees off from each other. And because they do that, the market for both—and for everybody else as well—is huge.

Apple’s punch to the smartphone market was vertical. It came up from below like a volcano and went straight toward the sky. With the iPhone, Apple showed how much invention and innovation the old original equipment manufacturer (OEM)–operator marriage had locked out of the smartphone marketplace, completely redefining the smartphone as a pocket computer that also worked as a phone.2 iPhones were beautiful, easy to use, and open to a zillion applications that were easy for programmers to write and for users to install.

The Google punch was horizontal. It came from the side, spreading its open Android platform toward the far horizons. As a platform, Android supported everything Apple’s iOS did—and more, because it was open to anybody, making it more like geology than a foundation. The old cartels could still build vertical silos on Android, but anybody could build just about anything, anywhere.3

So, while Apple shows how high one can pile up features and services inside one big beautiful high-rise of a silo, Google provides a way not only to match or beat Apple’s portfolio, but to show how broad and rich the open marketplace can be.

We need innovation in both directions, but we can’t see how complementary these vectors are if we cast the companies innovating in both directions as competitors for just one space. So, while it’s true that Apple phones compete with Android-based phones straight up, it’s also true that Apple makes phones and Google doesn’t.4 And, while it’s true that iOS and Android compete for developers, iOS only runs on Apple devices; there is no limit to the number and variety of devices that run on Android. In the larger picture here, Apple and Google are stretching the market in orthogonal directions. The result is a bigger marketplace for both and for everybody else who depends on smartphones.

Chief among those are users. There are now many more users of smartphones than of laptops, just as there are many more users of pockets than of cars. What smartphones do for users—specifically, for customers—is provide a box of tools customers can use to engage vendors in the marketplace. Liberated customers will rely on smartphones more than on any other single device. In other words, no device will be more essential to the development and growth of the Intention Economy than smartphones.

To understand what will make the Intention Economy spring forth from customers’ purses and pockets, let’s look at the orthogonal directions in which Apple and Google are taking us.

Steve Being Steve

To understand the iPhone, one must understand Apple, and to understand Apple, one must understand Steve Jobs. This is hard, because Apple is like Steve and Steve was unlike anybody. As a result, both are examples only of themselves: unique to a near-absolute degree. This is why it makes little or no sense to “be like Apple.” It can’t be done, except in some of the exemplary ways that Apple does what every other company ought to do, but too often neglects—such as customer service. But no company can do the one thing Apple does best, which is transform industries by opening up whole new markets, over and over again. That was what Steve did, and it’s not something any other company has ever done so well, and for so long—or is ever likely to do again.

Case in point: not long after Steve returned to Apple, one of the first things he did was kill off Apple’s clones. Naturally, a great cry of outrage went up. One response to the outrage was an e-mail I wrote to Dave Winer, which he published, on September 4, 1997:

So Steve Jobs just shot the cloners in the head, indirectly doing the same to the growing percentage of Mac users who preferred cloned Mac systems to Apple’s own. So his message to everybody was no different than it was at Day One: all I want from the rest of you is your money and your appreciation for my Art.

It was a nasty move, but bless his ass: Steve’s art has always been first class, and priced accordingly. There was nothing ordinary about it. The Mac “ecosystem” Steve talks about is one that rises from that Art, not from market demand or other more obvious forces. And that art has no more to do with developers, customers and users than Van Gogh’s has to do with Sotheby’s, Christie’s and art collectors …

The simple fact is that Apple always was Steve’s company, even when he wasn’t there. The force that allowed Apple to survive more than a decade of bad leadership, cluelessness and constant mistakes was the legacy of Steve’s original Art. That legacy was not just an OS that was 10 years ahead of the rest of the world, but a Cause that induced a righteousness of purpose centered around a will to innovate—to perpetuate the original artistic achievements …

Now Steve is back, and gradually renovating his old company. He’ll do it his way, and it will once again express his Art.

These things I can guarantee about whatever Apple makes from this point forward:

- It will be original.

- It will be innovative.

- It will be exclusive.

- It will be expensive.

- Its aesthetics will be impeccable.

The influence of developers, even influential developers like you, will be minimal. The influence of customers and users will be held in even higher contempt.

The influence of fellow business artisans such as Larry Ellison (and even Larry’s nemesis, Bill Gates) will be significant, though secondary at best to Steve’s own muse.5

I share this because I think we need at least some of what Steve did best, and what nearly all CEOs simply can’t do at all: create markets while proving out ideas in a contained vertical space that the founding vendor alone controls. While Apple’s controlling nature rubs my FOSS fur the wrong way, I cut Steve and his company some slack, because constructive creation is a good thing, and great artists can’t help wanting to control things.

Back in the mid 2000s, I was catching up with Tony Fadell on the phone. Tony at the time was vice president of engineering at Apple and involved in many successes there, starting with the iPod. (He resigned in 2008, but stayed on as a special adviser until 2010.) I’ve known Tony since the mid-nineties and found him exceptionally good at providing helpful intelligence about Apple while revealing absolutely nothing about the company’s secrets. On this call, he said, “If you want to understand Steve, don’t look at Apple, look at Pixar.” His points, from bulleted notes I took at the time:

- As few products as possible.

- Every product is original (nothing derivative).

- Every product is delightful, beautiful, successful, and profitable.

- Every product breaks new ground and moves both technology and art forward.

At that time, Apple Stores were still new, and few. Tony pointed out that there was nothing in the history of retailing that would encourage anybody to try starting another computer store. The smoking ruins of similar efforts by ComputerLand, Radio Shack, CompUSA, Circuit City, Gateway, and Sony all gave unanimously dire warnings. Meanwhile Dell and many other companies were kicking butt selling directly to individual customers or to the enterprise market. Yet Steve wanted to build out this new retail channel and knew it would succeed. And it did.

Likewise with the iPhone.

This is where another of Steve’s motivations comes in. He liked to fix product categories that are stuck or broken. That’s what the Macintosh did for personal computing in 1984, with its graphical user interface and simple industrial design. It’s what the iPod did for digital audio players in 2001.

Smartphones in the mid-2000s were so stuck in unholy alliances between operators and OEMs that little that was promising or cool had happened there—or would ever happen, if progress were left up to just those two parties. Apple broke that logjam by making its own phone: one that embodied all the numbered and bulleted points listed in my notes. Apple also eliminated billing complexity for mobile data, with the original, unlimited $25 per month data plan with AT&T.6 (Similar simplicities for phone call billing were beyond Apple’s reach.) This was huge, and would never have happened without inspired work on Apple’s part.

Then, in the summer of 2007, Apple opened the iTunes app store and introduced the iPhone 3G. The market for apps on smartphones exploded. This changed the handheld data device market forever, just as the Macintosh changed the PC market forever in 1984. The difference this time was that the iPhone became wildly popular, while the original Mac served mostly as a prototype.

But, even though the smartphone and app booms were huge, their dimensions were those of Apple’s vertical monopoly. The whole thing was contained within Apple’s silo. In order to grow, the smartphone and app markets needed to spread horizontally. That’s where Google and Android came in.

Google’s World

If Apple’s philosophy is Think Different, Google’s orthogonal corollary would be Think Same—by creating a big, wide open, and new market space, where lots of similar things could grow, outside of anybody’s silo.

That probably flatters Google a bit too much, because it’s not all-open and has its silos, too. (Plus other problems, some of which we’ve visited already and others of which we’ll tackle later.)

See, Google is a net-head company. In a deep and abiding way, it gets the Net and what the Net does for the connected world. Thus, Jeff Jarvis’s book, What Would Google Do?, might as well have been titled, What Would the Net Do? In Jeff’s words, the Net “commodifies everything.”7 Google and the Net do this to obtain because effects. Rather than make money with Android, Google wants to make money because of it. And it doesn’t mind lots of other companies making money because of it, too. In fact, that’s exactly what Google wants.

So, like Apple, Google wants to fix slow, damaged, or broken markets. But unlike Apple, Google wants to fix those markets by making them freer and more open for everybody—and therefore much larger as well. That is, to grow markets horizontally.

Google also likes to explore and demonstrate what can be done with a new idea, new code, new hardware technologies, new apps, new forms of infrastructure, and new ways of doing business. Google is also committed to open source and understands in its bones how open source works, which is horizontally rather than vertically. Those bones, by the way, are comprised of engineers: thousands of them, including the company’s two founders.

Open source building materials and designs are ideal for creating foundations of broad new markets. That was the idea behind Android, and that’s why Android succeeded. Thanks to Android, customers have a choice of more than one true smartphone and countless new, smart, handheld devices. No one hardware OEM can control those markets anymore, and developers have a choice of platforms other than Apple’s closed one.

True, there are problems with Android for developers, just as there are problems with Apple’s iOS. The biggest one with Android is too many target devices and too many feature differences among them. Developers had the same problem with RIM’s BlackBerry and Nokia’s smartphones, which have used several different operating systems and had radically different versions for different operators. The difference with Android is that there are still hundreds of thousands of applications working on Android devices and more coming out all the time, in spite of the complicated terrain there.

Generativity

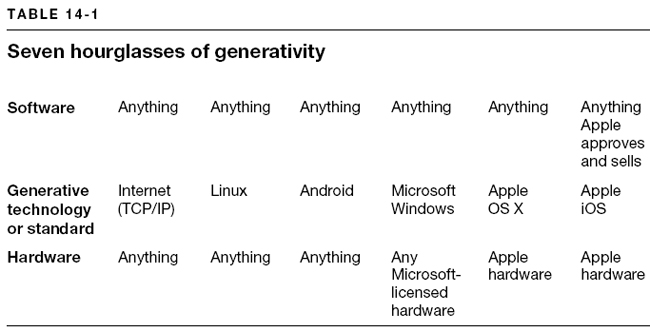

In The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It, Jonathan Zittrain borrows a word from biology to label the capacity of an enabling technology or standard to encourage boundless growth, in hardware, software, and usage. The word is generativity.

JZ (as he is known to friends) illustrates generativity with an hourglass.8 At the waist of the hourglass is the generative technology. Below the waist is all the hardware it invites, enables, and runs on. Above the waist is all the software and uses the technology invites and supports. His point: generative standards (such as the Internet) and technologies (such as generic PCs and mobile devices) invite, run on, and support a boundless variety of other standards, technologies, and uses, for both hardware and software. So, while platforms support only what runs on top of them, generative standards facilitate development below them as well as above.

Look at table 14-1 as seven hourglasses. Note that, for software, nearly anything runs on all seven standards (the Net) and technologies (popular computer and mobile operating systems). For hardware, the Net, Linux, and Android run on any hardware, while Windows runs only on licensed hardware (though there is a lot of that), while Apple’s operating systems run only on Apple’s hardware.

But there are advantages to vertical integration, and to control by one company. Apple’s products are famously beautiful, easy to use, backed by good customer service, and so brilliantly marketed that they often establish and define whole product categories. This is not something any company can do.

In all these respects Apple makes what Regis McKenna, Geoffrey Moore, and other marketing gurus call a whole product. That is, one that provides everything both customers and third parties need.

With Android, Google does not make a whole product—and doesn’t want to. Instead, it makes a purposely partial non-product that device makers, mobile service companies, and customers are free to complete in the form of their own products. In this way Google expands public markets horizontally—for everybody—at least as well as Apple expands private markets vertically. The difference is the one between a high-rise office building and the rest of the city. It is also the difference between the industrial and the information ages.

While Apple tries to build an all-encompassing company, Google equips everybody with a way to make an all-encompassing city that will be good for many companies.

At this early stage in the growth of smart mobile devices, progress in both directions has been dramatic. Apple’s iPhone continues to lead both in innovation and in customer entrapment. Android leads in opening opportunities for everybody on the World Live Web. Thus, Android became the world’s top-selling smartphone by the end of 2010 and will continue to lead until something even more live and open comes along.9

Closed Frontiers

Meanwhile, the problem today for both Apple and Android is that mobile operators still own the frontier, and they don’t like the mobile equivalent of “white box” (generic, functionally identical) computers. Not if those devices are going to connect to the Net over cellular phone and data systems, both of which are controlled by mobile operators—and by national laws that go back to the dawn of telephony.

My first encounter with this problem came in the summer of 2010, when I took a new Google Nexus One smartphone (intentionally a generic, white-box Android device, made for Google by HTC) to France for a few weeks, where I incorrectly assumed it would enjoy some of Bob Frankston’s ambient connectivity. After all, for years Europe has been way ahead of the United States in mobile telephony. I figured the same would be true of mobile data.

Not so. Outside the wi-fi zone in our rented apartment, the Nexus One failed completely as a data device, through no fault of its own. My chosen provider, Orange, sold me two data plans in a row that the phone burned through in a matter of minutes. The reason was that reasonable rates were available only with two-year contracts, and by French law those were available only to those holding French bank accounts. Unreasonable rates were what you got with prepaid plans. These rates were so high that not one of the four Orange stores I dealt with could tell me what they were. “Just don’t use data,” was the final advice of the last salesperson I bothered with the problem. So, after spending €75 and a week of troubleshooting failure, I gave up on data over mobile telephony outside the United States—at least until I could find a work-around.

“No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it,” Einstein said.10 This is why the carriers’ plans to turn the Internet into a big phone system will fail. End-to-end is simply a better way to get ambient connectivity than by endlessly improving the old phone system. But it’s impossible to see that future as long as we’re stuck in the framework of telephony’s past. That’s what we have with 3G, 4G, and all the bells and whistles of “high speed” mobile data service from phone companies.

The Net Rules

Every technology, every domain of science, has what are called boundary conditions between levels of an operational hierarchy. Take, for example, a mechanical clock. You can understand the clock at a number of levels. At the bottom level, the clock depends on the laws of chemistry and physics. Without good materials, you can’t make the clock. Above that, you have laws of mechanics. These depend on the laws of chemistry and physics but cannot be reduced to them. This is because chemistry and physics have a boundary above which they have nothing to say. Even if you know everything about chemistry and physics, you can’t explain mechanics with them. Likewise, the laws of mechanics are harnessed by the purpose of the clock, but you can’t use mechanics alone to explain the clock because the clock’s purpose is above the upper boundary of mechanics. If you were to disassemble the clock and lay out all its gears and other parts, you wouldn’t know what to make of them unless you understood that these make up a clock. In fact, the clock itself would make no sense unless you knew its purpose was to tell time. Thus, we have this hierarchy of domains, each of which has an upper and lower boundary.

In this sense, the Internet is about telling time, not about maintaining the mechanics for doing that. The mechanics of the Net are endlessly varied and substitutable. The Internet Protocol itself simply requires that a best effort be made to find a path from one end of the Net to the other. John Gillmore, civil libertarian and co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), famously said, “The Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.”11

This is an intentional design feature of the Internet and not just an accidental property. And this feature comes, at least in part, from study of the phone system by the Internet’s founding geeks. The phone system used what’s called “circuit switching,” which was ideal for billing everything that could possibly be billed. The Internet uses “packet switching,” which very pointedly does not care about billing. In fact, it was invented to relieve the world of a need for billing on networks.

That’s why the Internet is good for business, but not its own business. Business protocols—ceremonies of relationship, conversation, and transaction—are supported almost perfectly by the technical protocols of packet switching and best-effort data transport. And the cost of moving bits is not high, once the capacity is installed. Since fiber-optic cabling is capable of carrying enormous sums of data traffic, while disturbing the physical environment remarkably little (especially when compared to the easement and build-out requirements of electricity, gas, water, roads, waste treatment, and other public utilities), business should have a great deal of interest in seeing Internet infrastructure completed everywhere. But it can’t feel or express that interest if it can’t understand what the Internet is, or at least settle on one metaphor that makes clear how something so huge and stupid as the core of the Earth can be good for business.

A Frame for Business

We frame the Internet in many ways, but the most common three are transport, place, and publishing.

When we call the Internet a medium through which content can be uploaded, downloaded, and delivered to consumers through pipes, we’re thinking and talking inside the transport frame. We find it in the tech language as well. The Net’s core protocol pair, TCP/IP, stands for Transmission Control Protocol and Internetworking Protocol (together generalized as the Internet Protocol), and concerns itself with packets in the transport layer. The File Transport Protocol (FTP) and all the mail protocols also use transport language and framing.

When we speak of sites with domains and locations that we architect, design, build, and construct for visitors and traffic, we employ the language and framing of real estate, or place. We do the same when we speak of going on the Net, and when we call it a world, a sphere, a space, and an environment and ecology.

When we say we author, edit, put up, post, and syndicate things called pages, we employ the language and framing of publishing. When Dave Winer improved its technology and practices with RSS, the Web became even more of a publishing platform.12

We can’t help using all three frames, but the one that works best for all business (and not just those in transport, such as phone and cable companies) is place. That’s because it’s beginning to dawn on business that the worldwide marketplace we call the Internet is indeed a place, and that we’re leaving a lot of money on the table if both demand and supply are not sitting there, facing each other and dealing as equals. Personally. Anywhere. Even if the two are not in the same country or continent.

Wide Wins

Cities also grow in vertical and horizontal dimensions. Prosperous companies (and ones that just like to show off) build skyscrapers, while less vertical companies build their businesses on streets and crossroads where customers live and travel. For most of the last millennium, the biggest buildings at the centers of cities were churches or seats of government. Then, in the industrial age, the biggest buildings were retailing establishments and corporate headquarters, such as the Woolworth and Chrysler buildings in New York, and the Home Insurance Building in Chicago.

Today, Chrysler no longer owns or runs the building that bears its name. The Hancock name still resides on a pair of skyscrapers in Chicago and Boston, but the company that built them has since been absorbed into the Canadian company Manulife Financial, which may be called something else by the time you read this. The Sears Tower in Chicago now called Willis is also sure to be renamed again and again before it comes down.

Most major league sports fields and stadiums are now named after companies that pay for the privilege. Why build something when you can just buy “naming rights”? (Perhaps not coincidentally, the failure rate for buyers of naming rights for ball fields is rather high. Air Canada, CMGI, Enron, 3Com, PSINet, Adelphia, and Trans World have all been hit with what has come to be called the “stadium curse.”13)

No doubt the most beautiful building in California will be the new one Apple builds, according to a design led by Steve Jobs and approved by the Cupertino City Council after a pitch by the Man Himself in his last public appearance as CEO and less than two months before he died. Even more certainly, Apple will follow Steve to the grave. Unless it adapts.

This is an open question. What if companies open up, turn their silos inside out (see chapter 22), interact productively with everybody and everything, and become more citylike in the way they work in the world? Is that adaptive enough for them to survive?

Whether or not the answers are yes, the symbiosis between vertical and horizontal economic, social, and political entities will be better understood, especially after the amount of signaling explodes and far more—and better—research can be done.