23

EmanciPaytion

Only free men can negotiate; prisoners cannot enter into contracts. Your freedom and mine cannot be separated.

—Nelson Mandela1

The most important single central fact about a free market is that no exchange takes place unless both parties benefit.

—Milton Friedman2

Somewhere in the vast oeuvre of John Updike, I stumbled across this line: “We live in the age of full convenience.” It stuck my mind because it seemed perfect, yet had never been perfectly true—and never will be. In life, we often want more than we can get, and the delta between the two contains opportunity.

For example, sometimes when I give a talk here in the United States, I ask the audience a question: “How many people here listen to public radio?” Nearly all hands go up. Then I ask, “How many of you pay for it?” Around 10 percent of the hands stay up. (That’s a typical listener/customer ratio for public radio.3) Then I ask, “How many of you would pay if doing that was real easy?” Many more hands go up, usually about double the last number. Then, “How many of you would give if you didn’t have to wait through the stations’ fund-raising breaks?” More hands go up.

These hand raisings signal MLOTT (pronounced “m-lot”): money left on the table.

Clearly, there is more willingness to pay for public radio than there are means for doing so. This is surely the case for many other things as well. For example, I would love to be able to rent camera lenses that I can pick up when I arrive at an airport and then drop off when I pass back through. I’ve often wished for a business that provides a courier service to arriving business travelers, supplying projectors for laptops or forgotten laptop power adapters. When traveling, I also often find myself wanting to rent a specific car (say, one that seats seven, comes with a bike rack, and has satellite radio)—rather than the “or similar” that rental agencies happen to have on the lot at the time.

But, even though I’m usually willing to pay more for exactly what I want, that’s not how The System has been working in the age of adhesionism, and I have almost no direct input to that system other than to reinforce it by renting only what it offers me.

The problem in a general way is that means of engagement are constrained by systems on the sellers’ side that are rigged to ignore signals from buyers other than those that point to the standard list of offerings. Limited offerings are easy to rationalize, but the fact remains that there are many more signals that demand can send than it is able to now, or that supply is ready to hear. This fact suggests opportunity on both sides.

Public Advantage

Public radio has been begging for money since before the term public radio existed. Pacifica stations, starting in 1949 with flagship KPFA in Berkeley, California, called themselves “listener sponsored”—a term they still use. Noncommercial radio became “public” with the creation of National Public Radio (now just NPR) in 1970. More recently, the industry has been calling its category “Public Media,” to include not only public radio and TV, but podcasts, streaming over the Net, on-demand “content,” and many other kinds of stuff as well.

When ProjectVRM began, I thought public media (radio especially) might provide an ideal test bed for new VRM developments, especially around payment systems. Stations always need money, yet their systems for receiving it have always been limited by norms and practices that fall far short of what might be possible if listeners had more ways to give. Basically, stations make appeals for contributions on the air and on their Web sites and podcasts—then every few months, they hold fund-raising breaks when they turn off or interrupt programs to cajole listeners into making donations. This is what gets about 10 percent of listeners to help out. I figured we could easily raise that number just by improving means for giving on the listeners’ side.

One attraction was that public radio didn’t have many of the complications endemic to commercial retailing: no SKUs, no shipping, no pricing, no inventory management, no special hours. It had its own ways of taking in money, but there was nothing about them that precluded getting money in other new ways.

ProjectVRM also had connections through the Berkman Center. PRX (Public Radio Exchange), a public radio developer and producer like NPR, was located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and led by Jake Shapiro, who had also held a number of Berkman positions over the years. Our first ProjectVRM meeting at Berkman was on funding for public radio, which quickly made us a number of friends. Two of those, Keith Hopper of Public Interactive (now part of NPR) and Robin Lubbock of WBUR, were both very supportive. Keith became especially involved, as we’ll see shortly.

On the minus side, public radio had (and still has) a bad case of channel conflict. On the whole, listeners care more about programs than stations, and many of those programs are available directly by podcast, as well as over many different stations. Yet public radio is built for two-tier distribution. NPR and PRX sell programs to stations, which in turn sell them to the audience, which pays on a voluntary basis. If you like one program in particular, paying directly isn’t usually an option.4 You have to pay a station. This can cause problems. For example, take this blog post by Dave Winer on February 12, 2007:

WNYC spam

9 times out of 10, I don’t give money to public radio stations, because once you do, you never hear the end of it.

A few weeks ago, in response to a request for support from On The Media podcast, I gave $100 to WNYC. I don’t even live in NY. Now I’m getting a steady stream of spam from them with all kinds of special offers. This really sucks.

Of course I have asked to be removed from the spam list, and how tacky is it to ask for a pledge less than a month after getting a gift of $100.5

To its credit, WNYC has listened to people like Dave and has done its best to adjust its fund-raising systems. (Bill Swersey, director, Digital Media, for WNYC at the time, participated in early meetings and conversations with ProjectVRM.) But WNYC, along with the rest of public radio, is still on the cow side of the commercial Web’s calf-cow system. In fact, so is every organization that takes voluntary payments for goods that cost nothing for individuals to obtain.

Music is similar in the sense that you can get it for nothing, while some people are willing to pay something. A few well-known artists have taken advantage of this fact by selectively giving away some of their work. (Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails, for example.) Still, while the music industry’s business model is different than public radio’s, both have plenty of MLOTT.

Looking at public radio and the music business, I thought, “Hey, how about making it easy for anybody to pay (or at least offer) whatever they want for anything? For example, how about making it possible both to signal interest in paying, and to escrow the payment itself, or a pledge to pay?” ProjectVRM’s answer was EmanciPay.

EmanciPay

EmanciPay is a choosing system, rather than a payment system. Here are the kinds of things you might want to choose:

- How much to pay

- Where the seller can pick the payment up

- Whether this is a pledge or a payment

- What data to pass along with the payment

- Terms of use for personal data

Our first target market for EmanciPay was (and still is) public radio. Let’s look at two use cases I’ll call impulsive and considered.

In the impulsive case, you hear an especially good On The Media show and decide you want to throw a couple of bucks at the program. You don’t care that it comes from WNYC. You just like Brooke Gladstone and Bob Garfield, and feel like giving them something for a job well done. On your listening app, you bring up an interface that lets you select an amount, and you send it—but not straight to them. You have a payment service (say, a bank) that escrows the payment, waiting for WNYC to pick it up. You don’t have to become a member of WNYC, or you can express a willingness to do that, through choices four and five in the EmanciPay system. Either way, you’re in control. You’re not inside the systems of the radio app or of WNYC. You’re in your own system, which signals your intentions to the station.

In the considered case, you log all your listening and decide how much to pay (or pledge) to whom, based on what you’ve logged. Toward that end, Keith Hopper came up with ListenLog, which ProjectVRM built into a program that is now implemented in the Public Radio Player, an iPhone app from PRX. ListenLog tells what stations and programs I’ve been listening to, and for how long. In economic terms, it tells me what I value.

I can go a number of ways with ListenLog and the data it gathers:

- Decide how much to pay per minute or hour of listening, either up front or after totaling up findings.

- Decide what to pay to stations, programs, or other parties.

- Connect payment directly to listening.

- Share with others.

As I’m writing this, ListenLog is a prototype, a proof of concept. You should be able to take the code (it’s open source) and add, modify, or substitute what you like. For example, you might like to build in choices about payment rates for different kinds of uses. You might want to make it automatic, but with controls that are yours, rather than anybody else’s. Or you might tweak it to follow activities other than listening to media.

Now let’s go back to music. At this moment in time—at my house and possibly in yours as well—much of the world’s music listening takes place inside Apple’s iTunes, which logs a play count. In my own case, Weird Al Yankovic’s “Couch Potato” takes the lead with 104 plays, all by our son and his friends, back when they were about ten years old. Next is “Lay Lady Lay” by Bob Dylan, with sixty-eight plays. (I’m amazed that I’ve played it that much, but it’s possible I have.) Apple doesn’t provide a way for me to send more money to either of those guys (based on play count, or any other metric). Nor does it provide a way for me to send money to other artists I especially like or consider deserving of additional compensation. (One example is Mike Cross, a favorite of mine from my two decades as a North Carolinian).

I don’t want to wait for Apple to work something out with SoundExchange and other performance rights collection agencies, or with the artists themselves.6 I’d rather just keep track, put the money out there by some means, and tell the artists and agencies to come get it when they’re ready.

Toward that goal, I joined a group of people, several of whom were active with ProjectVRM, working with the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (better known as SWIFT), on new EmanciPay business model prototypes for banks and other financial institutions. Whether or not those prototypes pan out, we (in the largest sense) will standardize methods for making payment choices, escrowing money, recording pledges, notifying intended recipients that money awaits, and making the whole system secure. But for now, we just want to get the ball rolling.

ProjectVRM’s purpose with EmanciPay from the start has been to scaffold voluntary and genuine—rather than coerced—relationships between buyers and sellers in the marketplace. We want to give deeper meaning, for instance, to “membership” in nonprofits. (Under the current system, “membership” mostly means putting one’s name on a pitch list for future contributions.) We want to make the market truly free by giving any customer means for taking the lead, as well as for following. That lead includes signaling sums of value and extending hands with good intentions toward genuine relationships.

EmanciTerm

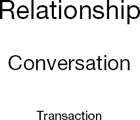

Three things happen in a marketplace: transaction, conversation, and relationship.7 In our industrialized world, transaction is the biggest thing (see figure 23-1).

FIGURE 23-1

Mass marketplace events

In the emerging world, where natural markets still thrive and serve as examples, the ratios are reversed (see figure 23-2).8

FIGURE 23-2

Networked marketplace events

In the mass marketplace, relationship wasn’t just subordinated to transaction. It is demeaned. We actually think, for example, that a mass-market vendor can (and should) control all the means by which relationships with customers should proceed. Still, as human beings, all of us also know we are capable of relating in our own ways and on our own terms, with anybody or anything. We also know our motivations are not all reducible to price. Many things are priceless, even in the marketplace. For example, relationships.

The commercial online world is very young. Born in 1995, it is still in high school. (Or, in the words of Frank Stasio, host of WUNC’s “The State of Things,” “It’s not old enough to download its own porn.”9) In the brick-and-mortar world, we have highly developed understandings of identity, privacy, friendship, and correct ways of interacting with strangers and familiar folk. There is enormous room for personal and cultural differences within these, and for improvisation.

We have nothing like that yet in the networked marketplace. “Friending” and “following” on Facebook and Twitter are barely at the stone-tool stage of what will become of civilized social interaction online. Both those activities also only work on those companies’ ranches. So, even if we become adept at using Facebook and Twitter, neither makes us adept as free agents in the vast marketplace outside Facebook and Twitter’s corporate reaches.

To work in the wild frontier of the networked commons, we are going to need instruments for relating as independent agents, and not just for transacting and conversing.

That’s the idea behind EmanciTerm. You offer your terms (including the legal ones listed in chapter 20). The seller makes its offer. It agrees or doesn’t, and you work out the differences, if you can.

This kind of thing is not complicated in the everyday world. First, we have very clear agreements already, both tacit and explicit, about what is private and what’s not, and about how and why we trust certain other people and institutions with private information about us. How we relate to our medical doctor, our financial adviser, our teacher, our student, our yoga instructor, our old friend, or the cop on the corner—all differ. And yet none of those require clicking “accept” to a pile of terms before we proceed.

We are years away from bringing this same level of casual ease to the online world. But those years will be decades if we don’t provide ways for individuals to make clear their intentions in the marketplace—especially for how we wish to be respected by entities we don’t yet know (or already know but don’t yet trust or barely understand).

Ascribenation

Over lunch several years ago, Bill Buzenberg, executive director of the Center for Public Integrity (CPI), told me how hard it is for CPI to get credit for the good work it does. It would do deep digging on one subject or another, produce a comprehensive report, and then watch as news organizations told the story while minimally crediting CPI as a source or not mentioning it at all.

Thinking about what Bill wanted here, I came up with the term ascribenation, which I chose in part because it wasn’t used by anybody yet and had no domain names using it at that time. In an April 2009 blog post, I defined ascribenation as “the ability to ascribe credit to sources—and to pay them as well.”10

In July 2009, the Associated Press, noting the same problem, issued a press release with this lead paragraph:

NEW YORK—The Associated Press Board of Directors today directed The Associated Press to create a news registry that will tag and track all AP content online to assure compliance with terms of use. The system will register key identifying information about each piece of content that AP distributes as well as the terms of use of that content, and employ a built-in beacon to notify AP about how the content is used.11

That turned into a proposed standard called Rnews.12 Another nascent standard called hNews13 also showed up. Both support ascribenation, though they don’t call it that (at least not yet). For VRM purposes, however, being able to say who you might want to single out for payment through EmanciPay is an interesting challenge as well.

Micro-accounting

When we talk about EmanciPay and ascribenation, the conversation almost always comes around to micropayments, and what’s wrong with them. So, to be clear, what we’re talking about here isn’t micropayments, but micro-accounting.

Accounting of small change has been around for a long time on the vendors’ side. Your phone company has being doing it forever. (Making nickel-and-dime into a verb.) It has also been happening with music on radio for most of a century and on Internet music streams since the turn of the millennium.

For example, the Copyright Arbitration Royalty Panel (CARP), and later the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB), both came up with “rates and terms that would have been negotiated in the marketplace between a willing buyer and a willing seller.”14 This language first appeared in the 1995 Digital Performance Royalty Act (DPRA), and was updated in 1998 by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).15 The rates they came up with have values such as $.0001 per “performance” (a song or recording), per listener, and have changed too many times over the years to bother citing.

Here’s the deal: EmanciPay creates the “willing buyer” that the DPRA thought the Net would not allow. It also can help the music industry do something it has failed to do from the beginning: stigmatize nonpayment for worthwhile media goods in a nonhostile and noncoercive way.

Micro-accounting, such as we have with ListenLog, can add up to many different ways for creators to be compensated for their work, by the market. That is, by customers. An individual listener, for example, can say, in effect, “I want to pay $.01 for every song I hear on the radio,” and “I’ll send SoundExchange a lump sum of all the pennies for all the songs I hear over the course of a year (or any other time period), along with an accounting of what artists and songs I’ve listened to”—and make dispersal of those pennies SoundExchange’s problem—or opportunity. (One it should like to have).

We can do the same thing for reading newspapers, blogs, and other journals. Heck, even for tweets, if Twitter is willing to risk a nonadvertising business model.

While all this might look complicated and labor-intensive for customers, it doesn’t have to be, once automated processes are set up, and much more activity becomes accountable.

Accountability is key. Everybody, including customers, should be able to record and audit whatever they do in the marketplace, as well as in the rest of their lives.

On the customers’ side, this is already happening through countless apps that track weight, exercise, spending, and other variables. Kevin Kelly, Gary Wolf, and friends have been on this case for years with their Quantified Self work. Adriana Lukas (a stalwart in the VRM community) and friends have been doing related work under the “self-hacking” label.

On the vendors’ side, a number of us (myself included) have been working with SWIFT (the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) on creating new business models for financial institutions based on EmanciPay, EmanciTerm, trust frameworks, and other VRM ideas. The first of those is a piece of infrastructure called the Digital Asset Grid, or DAG, described as a “certified pointer system pointing at the location of digital assets and the associated usage rights,” by SWIFT Innovation Leader Peter Vander Auwera.16

The vectors on both the demand and the supply side point toward a relationship that obsoletes old-fashioned marketing cruft (see chapter 8) and “confusopolies” (see chapter 14).

The difference between cruft and relationship is between what Umair Haque calls “thin value” and “thick value.” In The New Capitalist Manifesto he defines “thin value” as “artificial, often gained through harm, or at expense to people, communities, or society.”17 By contrast, “thick value” is “sustainable” and “meaningful.”18 You can’t get that by shooting messages at the feet of customers and saying “dance.” You get that by learning how to follow as well as to lead.