5

Asymmetrical Relations

CRM … moved from having been brought in as a platform for driving improvements in the customer experience, to being run as a platform for cost cutting and for risk management … in many cases all it did was move the waste/inefficiency on to the customer.

—Iain Henderson1

CRM came into vogue as a label in the mid-1990s, after sales force automation (SFA) met the Internet. SFA began as database marketing in the 1980s, but began to take off in a big way when Tom Siebel and Rebecca House founded Siebel Systems (now Oracle CRM) in 1993. Gartner projects $13.1 billion in sales for CRM vendors in 2012. That’s up from $8.9 billion in 2008.2 According to the research firm Trefis, the “Global Customer Relationship Management (CRM) Software Market has increased from $6.6 billion in 2006 to about $10 billion in 2009,” and has steady projected growth to $22 billion by 2017.3

Gartner, the giant analyst sometimes credited with coining the term CRM, continues to make a distinction between SFA and CRM, with the former as a subset of the latter.4 Currently, it ranks Salesforce at the top of both.5 Here’s what Salesforce says about CRM on its home page:

Customer relationship management (CRM) is all about managing the relationships you have with your customers. CRM combines business processes, people, and technology to achieve this single goal: getting and keeping customers. It’s an overall strategy to help you learn more about their behavior so you can develop stronger, lasting relationships that will benefit both of you. It’s very hard to run a successful business without a strong focus on CRM, as well as adding elements of social media and making the transition to a social enterprise to connect with customers in new ways.

The second person “you” and “your” are Salesforce’s corporate customers. Each of them has its own ways of relating to customers. So, while Toyota, Siemens, Starbucks, and Dell all use Salesforce to relate to their customers, as a customer of those four companies, you don’t have a single way to change your address or phone number with all of them at once. You have to do that separately with each. Multiply that work times all the different companies that see you as their customer alone and you meet a problem that CRM does not yet solve.

As a result, satisfaction with CRM’s work is not especially high at our end of the supply chain. In October 2010, Michael Maoz, vice president and distinguished analyst with Gartner, wrote,

Over the past ten years the level of customer satisfaction has edged up only slightly—for most industries in the vicinity of 3–5 percent. Considering that over US $75 billion was spent on CRM-related business applications in that time period, and triple that sum on process improvement, and hundreds of books written, you might expect better … 6

Yet this is not all CRM’s fault. CRM bears the full relationship burden because there are no corresponding tools on your side that allow you to manage many vendors in the same way vendors manage many of you. Those tools are coming, with VRM, for vendor relationship management. We’ll get to those in part III. Meanwhile, let’s take a closer look at where CRM is now, and where it’s going, on the way to meeting VRM.

Wasting Ways

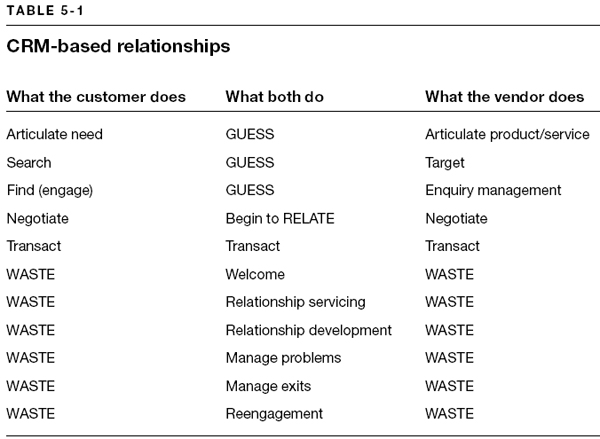

Iain Henderson, who labored many years in the CRM business, characterizes CRM-based relations as “islands of success surrounded by seas of guesswork and waste.” In relationships, the islands and seas look those in table 5-1, going through time from top to bottom (seas of guesswork and waste are in upper-case type).

The lowercase items in “What both do” and “What the vendor does” are all in the lingo of CRM, which has developed many ways of minimizing actual contact with customers and normalizing service around a minimized set of variables. This involves even more guesswork and waste than we can depict here—again, on both sides.

As a customer, you typically encounter this when your problem is not one of the few the call center provides when it says, “Press 4 for (whatever).”

In summarizing his research on CRM effectiveness for different kinds of companies, Iain rates CRM performance with different data types, which he gives green, yellow, or red markings. Green is good, yellow is blah, and red is bad. I’ve turned his graphics into a table with values: 1 for good, 0 for blah, and –1 for bad (see table 5-2).

Not all the companies studied had the same data types, and the data types have different weights, but this gives a good picture of how poorly CRM actually works.

Customer Disservice

Have you noticed how extra-friendly and concerned call-center people have become? Here’s the script-guided verbal handshake:

“Hello, my name is Bill. How are you today?”

“I’m fine. How are you?”

“Thank you for asking. I’m fine. How can I help you today?”

“My X is F’d.”

“I’m sorry you’re having that problem.”

They always ask how you are, thank you for asking how they are, and are sorry you have a problem. After loading Adobe’s latest suite of apps on one of my laptops, almost all my Adobe apps stopped working, including prior generations of the same suite. I spent three days on the phone with Adobe, unscrewing all the problems. I lost count of the number of people I spoke to. Except for the last call—the ultimately successful one—all the calls began with an exchange like the one recounted and ended by being dropped. And, in each case, the next service person at the call center said that the last person I spoke to marked down my problem as “solved.”

They even talk like that in chat sessions. A while back I had four chat sessions in a row with different agents of Charter Communications, the cable company that provides Internet service at a relative’s house. The sessions took place on a laptop in the crawl space below, where Charter’s equipment was located. Every chat was comically absurd and involved no institutional memory of the prior chat. The clear message that ran through the whole exchange was, We’re just here to give you a slow-mo dose of futility, and hope you figure out your problem in the meantime.

And many of us do. In fact, lots of us take up the slack where company support is absent or dysfunctional. In “Customer Service? Ask a Volunteer,” Steve Lohr of the New York Times writes about “an emerging corps of Web-savvy helpers that large corporations, start-up companies and venture capitalists are betting will transform the field of customer service.”7 He cites the work of enjoyment-motivated volunteers “known as lead users, or super-users” who have made unpaid contributions to product development in a diversity of fields, from skateboarding to open-source software. Then he asks, “But can this same kind of economy of social rewards develop in the realm of customer service? It is, after all, a field that companies typically regard as a costly nuisance and that consumers often view as a source of frustration.”

This is all part of a larger trend my wife calls “outsourcing customer service to the customer.” For evidence, she cites ATMs, self-service gas stations, self-service checkout in grocery stores, call-center mazes that send customers to Web sites, and Web sites that bury or refuse to reveal information (such as addresses and phone numbers) that would help a customer contact human beings at a company directly.

At its best, this kind of outsourcing falls into a creative category that Eric von Hippel, professor of technological innovation in the MIT Sloan School of Management, calls Democratizing Innovation (also the name of his best-known book).8 Demand and supply join hands and help each other out, in full respect for what the other side is best equipped to bring to the table both share. At its worst, you get customers wandering around in futility, occasionally venting on public forums, in faint hope that somebody else out there might be able to help solve a problem.

That was my own experience after a complete breakdown in communications with Sprint. The saga began when I got a “courtesy call from Sprint in July 2009, offering to “work out” a bill for more than $500, racked up, allegedly, when I went past the 5Gb per month usage limit on my laptop’s Sprint EvDO data card in June. I not only didn’t know Sprint had imposed a data limit, but had chosen Sprint as a mobile data vendor precisely because it didn’t have a data limit. And yet I was sure that my usual monthly usage was far less than 5Gb, and I hadn’t done anything that special in June. Surely there was a mistake somewhere. But the courtesy caller couldn’t look into that. All she could do was “work” with me. “What would you be willing to pay?” she asked. “Nothing,” I replied. The $59.99 per month I already paid was all the “work” I was willing to do.

Which wasn’t quite true. I had to find out what went wrong and fix it. So I called various numbers at Sprint and, at length, got exactly nowhere. So I put up a blog post titled, “What’s 10,241,704.22kb between ex-friends?” and hoped that exposing the problem to thousands of readers might get me somewhere.

It didn’t. Several months went by, Sprint cut me off, and then began to threaten action to collect the overage charge. So I tweeted an appeal to @SprintCares on Twitter, with a pointer back to my blog post. Somebody from Sprint then got in touch with me, checked back on my usage history and payment record, saw that the oddball month was a complete anomaly, and dropped the charges. (At this writing, Sprint is back to offering unlimited data again.)

Getting Social

I doubt that @SprintCares was part of whatever Sprint at the time had for a CRM system, and I suspect it still isn’t, more than two years later. But @SprintCares is considered part of a new CRM breed, called sCRM, for social CRM. Think of sCRM as a way for “social customers” to interact with companies, not as a new CRM offering. Not officially, anyway.

During the time I consulted for BT in the U.K., I watched sCRM start with one person solving problems for customers on Twitter using the handle @BTcare. This turned into a whole staff of customer service people, as @BTcare began working 24/7 to deal with customers engaging BT through Twitter, rather than through the company’s call center. Facilitating that move was J. P. Rangaswami, then the chief scientist at BT. He now holds the same title with Salesforce.

And, as a social customer myself, I have found sCRM very handy. For example, @CZ, a Verizon employee, has helped with my Verizon FiOS account. I’ve also had good luck engaging with other companies, as a journalist, by knocking first on the @CompanyName door. And, last but far from least, there’s my social experience with @Microsoft. Specifically, Microsoft Word for Macintosh 2011. Word is pro forma in publishing these days, and it’s what I’m using to write and edit this book. When something went wrong with the manuscript (I’ll spare you the gory details), I appealed to @Microsoft on Twitter and got help directly from the Word development team. Still, would everybody tweeting to @Microsoft get the same level of help? Kinda doubtful.

So there’s a huge gap here.

CRM vendors are addressing the issue with new “social” offerings for their customers, which are the companies that sell stuff to you and me.

In CRM at the Speed of Light, Paul Greenberg says we are now in “the era of the social customer,” that “the customer has taken control of the conversation,” and that the social transformation happening around CRM is much bigger than the one happening within CRM, or within business itself.9

No doubt that’s true. But CRM companies are pushing social hard now. In August 2011, Salesforce introduced The Social Enterprise, which aims to turn the company’s customers—businesses—into “social enterprises.” This means three things:

- Connect the company to social networks, including Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

- Create internal corporate social networks that work the same way.

- Make the company’s enterprise applications more social.

These are all good, but don’t cover the full range of what it means for individuals to be social in the networked world:

- Many customers are not on social networks, and never will be.

- Many customers on social networks wish to be social with companies only when there’s trouble, and don’t want to be contacted or pitched to at other times.

- Direct interactions between customers and companies are personal, not social.

- sCRM is so unlike the rest of CRM that integrating it is likely to take a lot of work and time.

For an example of how far the industry needs to travel on this new path, Greenberg contrasts the success of Bill Gerth—better known as @comcastcares on Twitter—with Comcast’s bottom-tier reputation for customer service. The latter is exemplified by the oft-told story of Mona Shaw, the Virginia grandmother who snapped after one too many mistreatments by her local Comcast office, trashed the place with a hammer, and got hit with only a small fine by a sympathetic court.