Chapter 13. Photos

It’s no wonder digital cameras are so popular: You don’t need film, you don’t need processing, and you don’t need extra shoeboxes to store the pictures until you get around to buying photo albums. And digital cameras are everywhere: in cellphones, on the ends of keychains, peeping out of PDAs, nestled in shirt pockets, and even hanging around the necks of tourists in Oahu. With all these cameras out there—and the human urge to communicate visually and share experiences—there’s bound to be a whole lot of digital photographs to see.

And there are. The Internet is brimming with pictures, from Web-based vacation photo albums to electronic snapshots of newborn babies. The Web’s vast archive of images is at your service for research purposes, too—with a few simple searches, you can go back in time and see the celebration in Trafalgar Square on VE Day in 1945, or Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington in 1963. Photographs have been documenting life on earth since the 1830s, but finding and sharing them has never been as easy as it is now.

Finding Photos

Locating pictures on the Web isn’t difficult at all, but finding pictures you actually want to see can take some search time. Using a site specifically designed to look for image files can speed things up.

Once you find a photo you want, you can drag a copy right out of your browser window to your desktop, where you can turn it into wallpaper, a screensaver, or some other decorative object.

You can use photos to illustrate personal newsletters, personal book reports, and personal whatever. Just don’t use them on posters, brochures, or other copyrighted material, because copyright laws come into play here. You need the copyright holder’s permission if you want to publicly reproduce the work for your own purposes. If there’s no photographer or photo agency name on the image file, try contacting the owner or Webmaster of the site where you originally found the image.

There are two types of sites where you can find photographs:

Photo-sharing sites like Flickr (www.flickr.com ) combine millions of images with an online community where members can browse each other’s work and post messages next to the photos. These sites are great for snaps of the Zeitgeist and modern daily life frozen in pixels.

Photo search sites like Google Images (http://images.google.com) can round up photos by analyzing whatever keywords were assigned to them. They’re even better at finding historical and commercial images.

Here’s what Flickr and Google have to show you.

Flickr

Flickr is a great big photo-sharing site (www.flickr.com) that lets its members upload and organize their own personal pictures. Both amateur and professional photographers use the service, which is free. And, since Flickr’s owned by (can you guess?) Yahoo, you can use your existing Yahoo ID.

You don’t need a Flickr account to browse or search the collections. But if you want to post a comment or download the full-resolution original of the photo (if it’s been made available), you need to sign up for a free account. (This section focuses on finding pictures; if you want to know more about uploading your own images to Flickr, flip to Section 13.2.2.)

Searching for photos on Flickr

Flickr encourages its members to tag their photos with keywords—text labels—to make them easier to find. (For more about tagging your own pictures, see Section 13.2.2.4.) For example, if you’re looking for photos of Paris, type paris in the box on the Flickr home page. Flickr puts tagged photos from a broad category into clusters, or subsets of the larger set (see Figure 13-1).

So when you get hundreds of Paris photos back from your search, look for a link for “Paris clusters” on the side of the page, which leads you to a page of more specific shots, like sacre coeur or louvre or seine, to drill down further. Click a photo thumbnail to see a larger version of it with more information, like the date it was taken, how many times it’s been viewed, and any comments people have left.

Each photo thumbnail on a search results page has a link to its photographer underneath as well, so you can go right to the person’s own Flickr collection (called a photostream) to see more. Each photostream can be divided up into sets by its owner, so you can hone in on a roundup of similar pictures like “airborne cats” or shots of fancy club chairs.

Flickr members can also see and join groups, which collaborate on pools of photos on a certain theme—say, Altered Signs (creative graffiti) or Rural Decay (rusting barns). Group members can upload contributions and post messages on public forums.

Tip

A picture’s worth a thousand words, but you can add a few more words by embedding notes in photos to point out certain elements or comment on parts of the picture. Point to a photo without clicking it. If there are notes attached, the text appears in a floaty yellow balloon. Both the photographer and the viewer can leave notes, and all the text within is searchable.

Flickr is especially great for finding photos of extremely current or offbeat events, because people can snap photos with their cellphone cameras and send them directly to their Flickr pages without having to stop and use a computer. Its freshness, along with its freeness and tagging features, make it easy to find quirky collections devoted to say, street art or underground events like New York’s annual Idiotarod race (where, instead of dogs and sleds, costumed teams of people push decorative, “borrowed” shopping carts along in a madcap race through Brooklyn and Manhattan). (To see some hysterical race-day coverage, search Flickr for idiotarod, as shown in Figure 13-1.)

Other Flickr features

If you have a Flickr membership, you can tag certain photos as favorites and send messages to other members with Flickr Mail. The Flickr staff itself helps round up the most interesting photos it can find each month and posts them on the Explore Flickr page, which is sort of a snapshot of all the different kinds of snapshots it’s added in the last 30 days.

Flickr may not be your best choice if you need a picture of Henry Ford for your school report on American industry, but it’s a great place to go to see a slice of life—even if it’s not your own.

Google Images

If you can search for it, Google can probably find it, and images are no exception. You don’t even have to remember or bookmark a new URL, either: Go to www.google.com and click the word Images above the search box. (But if that extra mouse click bugs you, just go to http://images.google.com.)

Searching for images on Google

To find pictures of something specific, type into the search box—Tom Cruise, say, or Sony HC3. Even Google can’t “see” a photo, recognizing what’s in it; it can only search the names of photos on the Web and whatever text keywords their creators have associated with them. (Google also takes a peek at text surrounding an image, deducing, for example, that a page with an unlabeled picture and a line of text that says “Look at my beautiful panda” probably contains an image of a panda.)

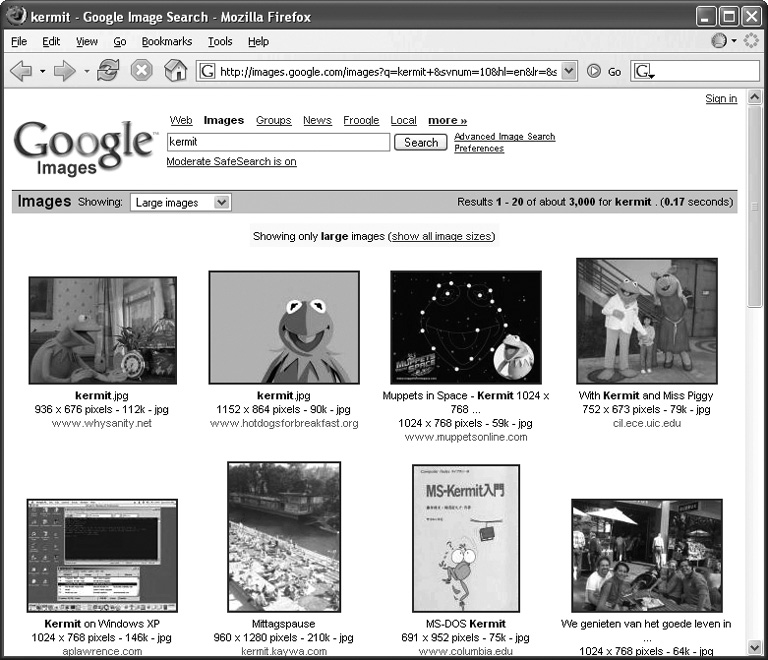

After you click Search, Google Images brings back a results page full of little thumbnail images, as shown in Figure 13-2.

Note

You can filter your results based on image size—small, medium, or large—which can make it easier to find, say, a photograph of a turkey that’s big enough to print clearly on your Thanksgiving dinner invitations. That’s important because Web graphics usually wind up blurry and pixilated when printed out. Turns out that a photo with enough pixels (resolution) to look good onscreen may not have nearly enough resolution for a printer. So the bigger the image file, the better chance you usually have of a decent print. In fact, you should probably avoid printing any photos Google designates as Small or Medium, unless you print them at very small sizes.

Each thumbnail tells you something about the picture, like the file name, how big the file is, and where it originally came from. Click the thumbnail to go to the original page, where you can see the image at its full size and in its intended context. Getting linked back to the original page is quite useful if you’re doing both photo and text research on a topic because the links often lead back to articles on the subject of your image search.

Google Images knows about photo files in the .JPG, .GIF, and .PNG formats (see the box in Section 13.2 for more about file formats). In addition to photographs, search results may include maps, charts, diagrams, and graphics. Search for pantheon, for example, and you get thousands of pictures of the old Roman temple, plus floor plans, cross sections, and virtual 3-D models of the building.

Fine-tuning a Google Image search

Getting so many results for general topics is more of a bad thing than a good one because you may have to wade through page after page looking for what you had in mind. To narrow things down a bit, here are a few tricks of the image-search trade:

Stick to short but specific keywords. Searching for kermit brings up thousands of pictures of a certain green cloth frog, but if you were actually looking for screenshots of the eponymous computer program or a photo of the 26th president’s son, specify kermit software or kermit roosevelt.

Fiddle around. Experiment with your keywords. Google can sometimes be inconsistent with its keywords for images, so what makes sense to you may not have occurred to Google. If you don’t like your results for 1974 volkswagen microbus, try volkswagen van or 1974 volkswagen bus.

Use the Advanced Image Search page. Similar to the Advanced Search page for text queries (Section 3.1.3), Google Images has its own full-page form to fill out. Click the Advanced Image Search link next to the search box to get to it. There you can specify file type, file size, or color mode (full color, grayscale, black-and-white) of the images you want to find. You also get some guidance on your choice of keywords and can instruct Google to look only within a certain domain.

Google generally tries to weed out pornographic images, but a few may occasionally slip through, depending on how you worded your search. You can use settings on the Advanced Search page to up the filtering to “strict” (in an attempt to screen out more of Those Types of Images) or turn filtering off entirely (if adult material is, in fact, what you’re looking for).

Tip

The search pages for Yahoo and MSN mentioned back in Chapter 3 have similar image search functions. If Google doesn’t goggle your eyes, try http://images.search.yahoo.com or http://search.msn.com/images.

Sharing Photos Online

If you have a digital camera, you no longer have to order multiple copies of photos and mail them to share with friends. Of course, you can still order prints for your friends who don’t have Internet access. Most drugstores and photo-processing places can give you a CD of your images even if you took the pictures with a film-based camera, so there are still many ways to share digital photos. But one of the most common ways is through a photo-sharing site, like the previously discussed Flickr.

Photo-sharing sites let you display pictures in an online album for friends and family to see. This means you don’t have to attach 15 pictures to an email message addressed to 30 people and clog up their inboxes; your buddies come to the photos instead. If the images are deeply personal, like pictures of a newborn baby that you want to share only with a close circle of family and friends, you can even password-protect your photo pages to keep strangers from wandering through.

Most photo- sharing sites let you turn your pictures into prints or novelty items like calendars, greeting cards, stickers, and mugs. Many of the bigger companies have a photo-book service where you can arrange to have a select group of images printed and bound in a paperback or hardcover album delivered by mail.

Uploading Your Images

How you get your pictures up online varies slightly depending on which photo-sharing service you decide to use, but the rough outline goes like this:

Find a photo-sharing site you like and sign up for an account.

Not surprisingly, a few of the big sites are owned by companies that sell digital cameras; you may get coupons, onscreen hints, or brochures inviting you to sign up when you install your camera’s software. Hewlett-Packard owns Snapfish, and Kodak owns EasyShare Gallery (both described in a moment). Depending on the site you choose, you may also need to install special software to do things like upload a bunch of images all at once.

Once you’re signed in, look for a link or button that says something like Upload Photos.

The site takes you to a screen and asks you to locate the pictures you want to put online. In some cases, you can just drag the pictures you want to use into the browser window. Other sites may require you to use a dialog box to navigate to the folder where the images are stored. (If you pulled them off the camera with Windows, check your My Pictures folder. Mac OS X fans, click your Pictures icon in the Finder window.)

Select the images from their location on the hard drive and upload.

Some services let you do minor image editing (like removing red eye or rotating a horizontal shot to a vertical one) before anyone else can see the pictures.

Along the way, you’re given the chance to tag your pictures (Section 13.2.2.4), arrange them in sequence, add captions, and perform other organizational tasks. You can also add a password to your photo page to keep it private.

Tell your friends where to look for your photos.

Some sites let you email a URL out to friends and family right there, or you can paste the new album’s link into an email message yourself and send it around. If you put a password on your pictures, be sure to give it.

That’s it. You’ve just created an online photo album—no glue stick or plastic sheets necessary.

Choosing a Photo-Sharing Site

The big photo-sharing sites all give you a place to publicly post your pictures and offer optional services like photo prints. Some may only give you a certain amount of space to store pictures online, especially if you have a free basic account with the site. If you’re a prolific photographer (or have a brand new photogenic kitten/baby/antique car), you may quickly max out the amount of space you’re allotted, but you can get more room to show off your handiwork with an upgraded account or additional fee.

Flickr

As mentioned earlier in the chapter, Flickr (www.flickr.com ) is a great place to find photos, but you can also use it to share your own. With a Flickr account, you can upload photos from your computer, send photos straight onto your page by emailing them, or send them directly from your camera-equipped cellphone; Flickr supplies you with the email address needed to post the images. You can order prints from a Flickr partner and, if you have your own blog (Section 19.1), you can also send copies of your pix right to your Web journal as well.

A free Flickr account lets you upload 20 megabytes’ worth of pictures a month. Flickr doesn’t measure that 20 megabytes by the amount of space your pictures take up on a hard drive, though, but by how much bandwidth you take up to get them online. Bandwidth is the amount of data you can transfer over a network from one computer to another.

Tip

High- resolution photos can weigh in at about one or two megabytes apiece, which quickly eats up your Flickr limit. Lots of pixels are great for quality prints, but a photo needs far fewer dots to look good on a computer screen. Reducing copies of your pictures to Web-friendly sizes, therefore, lets you upload more of them to Flickr; programs like iPhoto or Photoshop Elements can shrink a 2 MB picture down to a mere 300 kilobytes and still have it look fine online.

So why should you care about the bandwidth limit? Because the site’s keeping tabs on your bandwidth usage—and not the amount of hard drive space you’re occupying—deleting photos you’ve already uploaded doesn’t give you the ability to add more pictures if you’ve already hit your monthly bandwidth allowance. You either have to wait until the bandwidth meter is reset the first day of each month or give Flickr some money for an upgraded account.

If you choose a paid Flickr account for $25 a year, you get two gigabytes of uploads, unlimited photo sets ( Flickr’s version of the “album” feature in most photo organizer programs), ad-free pages, and permanent storage for archiving your high-resolution shots. (Free accounts get only three photo sets and can display only the 200 most recent photos.)

Once you’re signed in to Flickr, you’re ready to upload photos. Click the Upload link at the top of the page. The site gives you two ways to upload your pictures. You can use the Web form on the Upload page to manually select and tag six pictures at a time, as shown in Figure 13-3, or you can download the free Flickr Uploadr program that lets you put up a pile of pictures all at once. There’s a link for the Flickr Uploadr on the main Upload page, and the software works with most versions of Windows and Mac OS X 10.3 or later.

Tip

Industrious Mac/ Flickr fans have also created their own Mac-friendly upload programs (available right on Flickr.com), including a plug-in that lets you send photos right from iPhoto to Flickr—an incredibly convenient feature.

Using Flickr’s privacy settings, you can restrict pictures to just people you designate as Family, just Friends (in case you don’t want your Family to see those shots of you with the lampshade on your head), or both.

Once you’ve got your photos uploaded, you can use the Flickr Organizr to arrange them in sets or pools (Section 13.1.1). There’s a lot more fun on Flickr, so the best way to see it all is to sign up and dive in.

Shutterfly

If you want to make things with your photos (including prints) as well as share them online, Shutterfly (www.shutterfly.com) has plenty of projects for you. Like Flickr, you can either upload photos through Shutterfly’s Web page or with free utility software provided by the site after you’ve signed up and created a Shutterfly account. You can do basic photo editing with the site’s free tools, like crop images, apply color effects and borders, reduce red eye, and add captions to your images.

When you upload your pictures, the site guides you through sending out email invitations for people to come see the photos at your own Web page address, with optional password protection. People on your list have the opportunity to order prints of your work from Shutterfly, so Grandma can take matters into her own hands if she feels she’s not getting enough action shots of the grandkids to suit her.

You can make all sorts of things out of your uploaded photos and order the finished products: photo books, calendars, coffee mugs, T-shirts, tote bags, playing cards, mouse pads, coasters, jigsaw puzzles, and more. All kinds of photo albums and brag books are available, too; you can even reproduce a photo on canvas with fade-resistant inks. For about $150, that shot of the two of you at the Left Bank café on your honeymoon can become a 24 x 36-inch framed portrait hanging over the couch.

Snapfish

Snapfish (www.snapfish.com) doesn’t care if you don’t have a digital camera. It politely offers to process your 35mm and APS film rolls, send you prints and negatives, and put all the pictures online—all for $3 and mailing costs.

If you do have a digital camera, you can upload your images right from your computer, email them from a computer or cameraphone, and order prints.

A Snapfish account is free and lets you store as many pictures as you’d like. You can let your friends and family see your online albums in the usual way: sending them an email invitation with a Web link and a password. Like Shutterfly, you have basic image-editing tools at your disposal to crop, rotate, and adjust colors in your pictures.

Along with film processing, Snapfish makes its cash by selling you all sorts of objects adorned with your images—mini-soccer balls, shirt-wearing teddy bears, golf towels, candy tins, boxer shorts, baby bibs, pillowcases, and more—to show off your photographic efforts on a variety of surfaces.

Kodak EasyShare Gallery

Kodak’s online gallery (the sharing site formerly known as Ofoto) adds a sense of history to the notion of Web-based picture pages. Kodak, after all, has been in the consumer photography business since 1888, which is plenty of time to figure out how people like to take and share pictures. It even offers famous archival images from Life magazine for sale in its gallery pages, including the photograph of Margaret Bourke-White snapping pictures atop the Chrysler Building, an astronaut walking on the moon, and a cow wearing a cowboy hat (Figure 13-4).

To get started on the personal part of the Kodak Gallery, sign up for a free account at www.kodakgallery.com. (If you have a Kodak digital camera, the EasyShare software that came with it makes it easy to upload your pictures to your EasyShare Gallery page.)

With your free account all set up, you can upload images one at a time at the Web site, or in batches with special Mac or Windows software. Like Snapfish, Kodak also accepts and processes film rolls by mail for a few bucks; it will automatically park digital copies of the resulting prints on your EasyShare page for you.

You can send out invitations to select viewers, enhance your images with basic editing tools, and create online slideshows from your pictures. If you like one of your pictures so much you want to carry it around with you like a wallet photo, you can transfer your photos to your cellphone with the Kodak Mobile Service for $3 a month.

This being Kodak, you can order all sizes and kinds of prints right from the site, plus photo-decorated tchotchkes like mugs, tote bags, and calendars. Paid “Premier” Gallery accounts, starting at $25 a year, give you more flexibility in what your home page looks like and discounts on prints.

Sending Photos to a Printing Service

All four of the big photo-sharing sites offer printing services, should you decide you want some hard copies of your pictures. True, printing photos at home on an inkjet photo printer has an appeal all its own—namely, that you get the pictures right now. But, the truth is, when you factor in the special photo paper and all the ink those printers guzzle down, you might find that, economically speaking, ordering prints online is actually a better deal.

Flickr, Shutterfly, Snapfish, and Kodak let you order prints in all shapes and sizes and have them mailed right to you. The Web is also crawling with services that do nothing but create prints (and de-emphasize all the photo-sharing stuff):

Winkflash. You can upload your photos to Winkflash and use the site’s free organizing and editing program (Windows only) before ordering prints. If you connect to the Internet with a dial-up modem and don’t particularly relish the thought of spending the entire weekend uploading photos, Winkflash will mail you a CD; you burn your photos to it and mail it back to them with your print order form. (www.winkflash.com)

dotPhoto. With free software for Windows folks called dotPhotoGo, you can crop, adjust, and upload your digital images to the site. Basic membership is free, provides Web space to show off pictures, and lets you order 3 x 5-inch prints for 15 cents each. Monthly plans ($5 and up) give you a certain allotment of prints per month. (www.dotphoto.com)

Walgreens. The venerable Main Street drugstore chain has gone high tech. You can upload your pictures to Walgreens’ photo site or email them in (even by cameraphone) to place your print order. If you live near a Walgreens store, you can pick them up in person an hour later; alternatively, the service can mail you the goods. The digital pictures you upload for printing stay on the site—no charge—and can be viewed by your pals. (http://photo.walgreens.com)

Wal-Mart stores (www.walmart.com/photo-center) have jumped into online photo-processing with in-store pickup as well, so check with your area stores to see if that’s an option.

Tip

Mac OS X fans can order and buy prints, cards, calendars, and photo-books right from the iPhoto program that comes free on new Macs. Those with .Mac accounts ($100 a year at www.apple.com/dotmac) get a gigabyte of online storage to use for email accounts and displaying photos.

If you, your friends, and family use iPhoto 6 (or have an RSS reader—see Section 5.5), you can even publish photocasts. These are sets of pictures that you’ve broadcast to selected friends and family, which they can view online at no charge. What’s cool is that every time you update your set of “published” photos, your subscribers can see the changes, too.

Sending Photos via Email

If you just have a few photos you want to share—or would prefer to keep Web sites out of it for whatever reason—sending pictures as email attachments (Section 14.3) is still a perfectly fine way to send them around to your friends.

There are several ways to attach a picture (or pictures) to an email message, including:

In Windows, right-click a photo file or selected group of files (on your Desktop or in your My Pictures folder or wherever) and choose Send to → Mail Recipient from the shortcut menu. Your email program opens a new outgoing message, with the photo already attached; just address and send.

On the Mac, drag photo files from your desktop onto the Dock icon of your email program (Mail, Entourage, or whatever). Once again, the program is smart enough to get the hint; it creates an outgoing message and attaches the files, ready to send. (You can also drag photos into the body of an outgoing message you’ve already created.)

If you keep your pictures in iPhoto, it’s equally easy: Select a photo (or several) and then click the Email button at the bottom of the window. The beauty of this approach is that iPhoto offers to resize the photos to screen resolution before sending them (read on).

If an outgoing message is already open and addressed in your email program, click the Attach File button. The standard Open File dialog box appears; navigate to the place on your hard drive where the picture you want to send lives.

Before you try any of these techniques, however, steel yourself for the Email Resolution Nightmare.

The Email Resolution Nightmare

The most important thing to know about emailing photos is this: full- size photos are usually too big to email.

Suppose, for example, that you want to send three photos to some friends—terrific shots you captured with your 5-megapixel camera.

First, a little math: A typical 5-megapixel shot might consume two megabytes of disk space. So, sending along just three shots would make at least a 6-mega-byte package.

Why is that bad? First, it will take forever to send (and for your recipients to download). Dial-up email accounts gag and crash as they attempt to retrieve a message with a huge photo attachment.

Second, the average high-resolution shot is much too big for the screen. It does you no good to email somebody a 5-megapixel photo (3008 x 2000 pixels) when his monitor’s maximum resolution is only 1024 x 768. If you’re lucky, his graphics software will intelligently shrink the image to fit his screen; otherwise, he’ll see only a gigantic nostril filling his screen. But you’ll still have to contend with his irritation at having waited 24 minutes for so much superfluous resolution.

Finally, the typical Internet account has a limited mailbox size. If the mail collection exceeds 5 MB or so, that mailbox is automatically shut down until it’s emptied. Your 6-megabyte photo package will push your hapless recipients’ mailboxes over their limits. They’ll miss out on important messages that bounce as a result.

For years, this business of emailing photos has baffled beginners and enraged experts—and, for many people, the confusion continues.

So, how do you avoid the too-big photo problem?

On the Mac. iPhoto offers to shrink your big photo files into mail-friendly sizes, like 640 x 480 pixels.

In Windows. As shown in Figure 13-5, Windows XP offers to resize your photos for email when you attach them from the desktop, so take it up on its kind offer. Most consumer-oriented photo programs—Photoshop Elements and Google’s free Picasa program, for example (http://picasa.google.com)—make this offer, too.

Reducing the image size not only makes it easier to email, it makes the photo easier to see as an email attachment on the recipient’s end.

File Formats

The JPG format is the lingua franca of photos on the Internet; both Web sites and email programs can display them. Conveniently, that’s exactly the same format produced by most digital cameras.

There are a couple of cases when an emailed photo might show up blank in your audience’s inboxes:

It wasn’t actually a JPEG file. Fancier cameras can take pictures in something called RAW format, which professionals like because it offers fantastic editing flexibility in Photoshop (but which consumes appalling amounts of disk space). Email programs (and Web browsers) generally can’t display RAW files.

It wasn’t in RGB mode. Most cameras describe the colors in a photo using a scheme called RGB (in which each pixel has a specified amount of Red, Green, and Blue). It’s possible, however, that you’ve sent a photo that somehow got converted to the CMYK mode used in the printing/publishing industry. (It stands for Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Key, better known as Black.) CMYK photos generally don’t show up in email programs, either.

So, if you’re mailing out digital images, here’s a checklist to make sure your recipients have the best shot at opening the files:

Use the JPEG format, in RGB mode.

Reduce the size of large files to make them easier to handle. Most photo programs have a pre-set resolution of 640 x 480 pixels for emailed images, which is a decent size to see and send photos.

Don’t send too many images at once, so as not to overwhelm your recipient’s mail program—or senses.

If you have other questions about sending files by email, getting and organizing email, or even how to set up your email account, you don’t have to go far for answers. In fact, just flip to the next chapter.