2

Understand Yourself

Vincent Siciliano, CEO of California-based New Resource Bank, shared with us the story of how he started with the bank. He was brought in to turn the bank around and restore it to its founding mission. When he showed up, all the other members of the executive team resigned, giving him the opportunity to rebuild with people of his own choice. Within a few years, under Vince’s leadership, the bank was back on track in terms of profitability and mission alignment.

The leadership team decided to take the pulse of the organization and launched the bank’s first employee survey. The results revealed low levels of engagement and criticism of senior leaders. Vince assumed this was left over from the many changes the organization had gone through and chose not to take any action.

A year later, the bank sent out another employee survey. This time, the results were more specific: morale was a significant issue and the majority of people, including members of the senior leadership team, identified Vince as the root cause.

Vince was crushed. His mind oscillated between anger, indignation, defensiveness, and blame. He wondered, “How could they say these things about me? Don’t they understand how far we’ve come under my leadership?” He could have stayed in this negative mindset, wallowing in self-pity and searching for excuses. Instead, he decided it was time to take a hard look at himself. Despite being a high achiever and successful throughout his career, Vince came face to face with an uncomfortable truth: he wasn’t the great leader he thought he was. He was leading by the book and trampling over the concerns of others who were not ready to move so fast or didn’t understand reasons for changes.

In our conversation with Vince, he said: “There was a gap between my internal reality and my external behavior. My ego had run amok. I was leading from my head and not from my heart.” He realized that despite all the skills he had developed through his years of management education and professional development, he’d never been directed to take a long look in the mirror and ask questions about who he was, what he valued, and what it really meant to be a leader.

Bill George, a Harvard leadership professor, former CEO of Medtronic, and author of True North, says that self-awareness is the starting point of leadership.1 Self-awareness is the skill of being aware of our thoughts, emotions, and values, moment to moment. Through self-awareness we can lead ourselves with authenticity and integrity.

Vince’s experience is not unique. Self-awareness is not standard curriculum in most management education programs. The majority of MBA degrees focus on strategy and profitability—the things Vince excelled at. But this focus blinded him to what was actually happening in his organization.

Approximately 40 percent of CEOs are MBAs.2 Many large-scale studies have found that leadership based solely on MBA-trained logic is not enough for delivering long-term sustainable financial and cultural results, and that it often is detrimental to an organization’s productivity. In one study, researchers compared the organizational performance of 440 CEOs who had been celebrated on the covers of magazines like BusinessWeek, Fortune, and Forbes. The researchers split the CEOs into two groups—those with an MBA and those without an MBA—and then monitored their performance for seven years. Surprisingly, the performance of those with an MBA was significantly worse.3 Another study published in the Journal of Business Ethics looked at the results of more than five thousand CEOs and came to a similar conclusion.4

To be clear, we’re not saying MBAs are not useful in leading an organization. But if the linear MBA-trained logic becomes the sole focus—at the cost of other skills, like self-awareness—the leadership approach is out of balance.

That was the case for Vince. He had all the numbers right. His strategy was clear. But people didn’t like working with him and were increasingly unhappy. He was managing based on prevailing business theories, but he didn’t know or understand himself. Because he lacked self-awareness, people found Vince inauthentic. Subsequently, they weren’t keen to follow him or support his leadership. Luckily for Vince, he was open to change and through a journey of mindfulness and coaching toward developing self-awareness, he was able to become more of the leader he wanted to be.

Self-awareness is where leadership starts. We must have awareness of ourselves to lead ourselves. In this chapter, we start by exploring self-awareness, examining how our mind works, and introducing how you can gain better self-awareness through mindfulness. Then we explore the importance of values, followed by a look at what it means to truly be happy. Finally, the chapter ends with practical tips for increasing your self-awareness.

Self-Assessment versus Self-Awareness

Many leadership development programs start with some form of self-assessment. But what do you actually learn from these assessments? In truth, most assessments just scratch the surface of who you are. Sure, they might provide you with insights into dominant traits and behaviors. But is that the real you?

Take a moment to consider the last assessment you did. What did you learn? Perhaps you discovered that you are a visionary thinker and it’s hard for others to keep up with your innovative strategies. Perhaps you learned that people find you unapproachable and you need to work on engagement.

These types of insights can be valuable; they can help you understand yourself and how you work with others. But they don’t necessarily provide you with the tools needed to solve difficult or complex leadership challenges. To do that, you need real self-awareness.

Take Maura McCaffrey, CEO of Health New England, a US health insurer. Like many CEOs, she’s passionate about her work and driven to get results. In her early years as a leader, this passion could occasionally create challenges. As she described it, “I would enter a meeting with a clear strategic plan and, without taking the time to engage others, move forward. I felt so strongly about it, no one could stop me.” Call it passion-bias. Her drive for results would lead her to steamroll the group into following her plan, regardless of objections or suggestions.

A 360-degree assessment illuminated this issue. The assessment was clear, but how to move forward was not. The assessment itself didn’t provide the tools to fix the problem. Instead, self-awareness did. With the help of mindfulness, Maura gained a new level of self-awareness and started to understand the downsides of her passion-bias. She began to understand how this drive was not always beneficial for her relationships, team engagement, or alignment with her values or organizational objectives.

Self-awareness is what enables you to translate the insights from an assessment into action. Self-awareness is getting to know yourself, moment by moment. Self-awareness is knowing what you are thinking while you think it and what you are feeling when you feel it. It’s the ability to keep your values in mind at all times. Self-awareness is the ability to monitor yourself so you can manage yourself accordingly.

In Maura’s case, self-awareness was what enabled her to monitor her behavior and change it in the moment. Self-awareness allowed her to notice when her passion-bias was about to manifest itself and take a pause. She learned to become more inclusive in her ways and engage others at their pace. Yes, it could sometimes take longer to put strategies into action. But in the end, those strategies showed much better results, because the people on her team were more engaged and better able to follow through on a vision they helped create.

A general lack of self-awareness, like Vince and Maura experienced in their early leadership years, is one of the key factors in many of today’s leadership issues and leadership failures. But to have better self-awareness, we must first understand how our mind works.

Welcome to Your Mind

Who manages your mind? The answer may not be what you think—or hope—it is. Here are a few facts all leaders should know about their mind:

You do not control your mind.

You are not rational.

You are not your thoughts.

The first point: You probably don’t control your mind as much as you think. To test whether that’s true for you, focus on any word in this sentence for a full minute. Don’t think about anything else. Don’t get distracted. Just focus on one word for a full sixty seconds. No cheating. Okay, go ahead.

How did it go? Were you able to maintain complete focus for a minute? Or did you question the purpose of the exercise? Did you debate which word to focus on? Did the word catalyze new thoughts, leading you to think of other things? The point is that if you strayed from complete focus on that one word, you failed in leading your own mind, even just for a minute.

If you failed, don’t worry. You’re normal. Most people fail this test. Why? Researchers have found that on average, our mind involuntarily wanders nearly half our waking hours.5 While you think you’re managing your mind, you’re not. Think for a moment about the implications of your mind being distracted from what you’re doing nearly half of the time. How might it impact your effectiveness? How could it affect your ability to be present with others? How might it impact your well-being?

The second point: You are not rational. Sure, we like to think we’re rational beings. But in truth, we make choices based on emotions and rationalize them afterward. For example, numerous studies confirm that our decisions are influenced by how options are framed. In one study, faced with making a medical decision, subjects chose the riskless option when outcomes were positively framed in terms of gains, and the risky option when outcomes were phrased negatively in terms of losses.6

The third point: Your mind creates your reality. Consider the last time you believed you led a meeting where everyone was perfectly aligned, only to later find out that some participants perceived it differently. This type of situation happens all the time. We all have unconscious biases that influence and filter everything we experience. Put more succinctly: we don’t perceive things as they are, but as we are. Literally, our mind creates our reality.7

The fourth, and final, point: You are not your thoughts. In the vast majority of cases, thoughts arise randomly in the mind.8 But they’re not you. Instead, they’re just events playing out in your mind, as if your mind is arbitrarily flipping through TV stations. We often identify with our thoughts, believing they are true and believing they define who we are. And that’s a problem, since we have thousands of random, repetitive, and compulsive thoughts every day. They’re random because they often come out of nowhere, and for no reason, such as thinking about a meeting you attended earlier in the day while you’re trying to be present with your family. They’re repetitive because we often repeat the same thoughts again and again, like a childhood memory that comes to mind thousands of times throughout life. And they’re compulsive because they just keep coming, flowing like a waterfall, even if we try to stop them.

Think about it this way. Have you ever had a bad thought? Does that make you a bad person? Of course not. But when you identify with your thoughts, you become their victim. This is especially true if you tend to be critical of yourself. Then every mistake means you’re “stupid,” “lazy,” “incompetent,” or a “failure.” To avoid being victimized, don’t believe all your thoughts.

These mind facts should be concerning, especially for leaders. If we as leaders don’t manage ourselves, how can we lead others effectively, and, ultimately, lead our organizations? This challenge is best faced by first understanding more about the mind, how it works, and how it can be trained.

The mind and the brain are not the same thing. Your brain is the 85 billion neurons, between your ears, as well as the 40 million neurons around your heart and 100 million neurons in your gut.9 In contrast, your mind is the totality of your experience of being you—cognitively, emotionally, physically, and spiritually. When we speak about the brain, we refer to the physical collection of neurons in our heads and bodies. When we speak about the mind, we refer to the bigger perspective of being ourselves.

Neuroscientists have found that by training our mind, we can change our brain.10 Physiologically, we can change the structure of our brain by training our mind. When this happens, we can become more focused, kinder, more patient, or any other qualities that we train for. Simply put, what we do is what the brain becomes. Focus for ten minutes every day for two weeks, and our prefrontal cortex—a part of our brain that contributes to focused attention—is strengthened.11 The brain is taking shape according to how we use it. Scientists and researchers call this neuroplasticity.12

Neuroplasticity is great news for all of us. It means that we’re not limited by the faculties and aptitudes we’ve already developed. On the contrary, we can keep learning and growing and can effectively rewire our brain throughout our entire lives. And as leaders, we can learn to better manage our mind.

But here is an important caveat for neuroplasticity. Just because our brain is constantly changing doesn’t mean that it’s automatically changing in ways that are helpful to us. In fact, in our distracted work environments, we tend to rewire our brain to be more distracted. If those sentences make you think about your smartphone or meeting schedule, you’re on to something. If we’re constantly asking our brain to shift from one task to another, our brain’s ability to focus on a single task will diminish. And if we allow ourselves to be constantly impatient and not particularly kind to others, these two characteristics can become the default operations of our brain. In this sense, we get the brain we get based on how we use it. Which means we should all place greater value on creating and managing our mind in ways that are beneficial to us as leaders and the people we lead.

But make no mistake: this process is not easy. It requires training. It requires effort. It also requires a deep understanding of yourself, your values, and your behaviors. But how do you begin to know yourself more deeply and gain this type of self-awareness?

A Mindful Path to Self-Awareness

The starting point for self-awareness is mindfulness. In a busy, distracted work life, focus and awareness—the two central characteristics of mindfulness—are the key qualities for effective mental performance and self-management. As we become more aware of our thoughts and feelings, we can manage ourselves better and act in ways that are more aligned with our values and goals.

Focus is the ability to be single-mindedly directed in what you do. Focus is what allows you to finish a project, meet your goals, and maintain a strategy. When you’re involved in an important conversation, focus is what enables you to stay present and not mentally wander off.

Awareness is the ability to notice what is happening around you as well as inside your own mind. When you take part in a conversation, self-awareness allows you to know what you’re thinking, recognize how you’re feeling, and understand the dynamics of the conversation. Awareness is also the quality that informs you when your focus goes astray and helps you redirect it back on track.

Our previous book, One Second Ahead, is an extensive manual for developing mindfulness at work and being in the upper right quadrant of the mindfulness matrix presented in chapter 1.13 The book provides practical tips on how to enhance effectiveness and well-being in daily work life by bringing mindfulness to tasks like email, meetings, prioritization, and goal setting. We won’t repeat all the directions for developing and maintaining a mindful practice here; instead, in this chapter, we’ll look at the mindful characteristic of awareness and how you can cultivate self-awareness as part of your own leadership practice. Chapter 3 will look at how mindful focus enables more effective self-leadership skills.

Shut Off the Autopilot

We all have the powerful illusion that we’re consciously in charge of our actions and behavior at all times. But in fact, scientists estimate that 45 percent of our everyday behaviors are driven by reactions below the surface of our conscious awareness.14 This may sound like bad news, but it’s necessary and extremely valuable. Imagine trying to drive a car if you consciously had to remind yourself to push the pedal to speed up or ask your hands to move when you needed to turn the wheel. You’d be overwhelmed—and you probably wouldn’t get very far. In certain circumstances, these autopilot actions, reactions, and behaviors are vital. These unconscious processes allow you to perform tasks without having to think about them. But not all your autopilot actions and behaviors are useful in leading yourself or others.

As leaders, we impact the people we lead. They pick up on every subtle cue we send, whether we send it consciously or unconsciously. And many of the cues we send can be discouraging, distancing, or confusing. This is not necessarily due to bad intentions, but rather because the behaviors, actions, or reactions happen while we’re operating on autopilot. Therefore, gaining greater awareness of our subtle actions and behaviors, and eliminating autopilot behaviors that are detrimental can be highly beneficial.

Mindfulness training enables us to expand our awareness of what’s happening in the landscape of our mind from moment to moment. It also helps us pause in the moment, so we can make more conscious choices and take more deliberate actions. These are powerful skills to have as a leader.

Fortunately for all of us, awareness can be enhanced. We can change the ratio of our conscious to unconsciousness behaviors, which can make the difference between making good or bad decisions. But what is awareness really? Do you know what awareness feels like? Take a moment to experience it:

Let go of this book. For one minute, sit still.

Whatever comes into your mind, be aware of it. Simply notice it.

Let go of any inner commentary of why you are doing this exercise.

No analyzing, no judging, no thinking.

Simply be aware.

Just be.

That is awareness. A direct experience of what is happening for you, right now. And paying attention to it helps us understand ourselves. Did you become aware of anything about yourself that you were not aware of before the exercise? Did you find that maybe you’re tired? That you perhaps felt tension or stress somewhere in your body? Or that you have a lot on your mind? What did you discover?

If you didn’t actually do the one-minute exercise, go back and actually try it.

If you found the exercise difficult, you’re not alone. In our busy lives filled with constant distractions, our mind is often racing. The flood of activity can feel like a waterfall pouring down on us with a million bits of information. As a result, we’re less aware than we should be. Simply because our mind is too full to be aware. Mindfulness can address that. At the end of this chapter, you’ll find simple tips and reflections for mindful awareness training. This training empowers you with greater awareness throughout your day. How? By helping you get one second ahead of your autopilot reactions and behaviors.

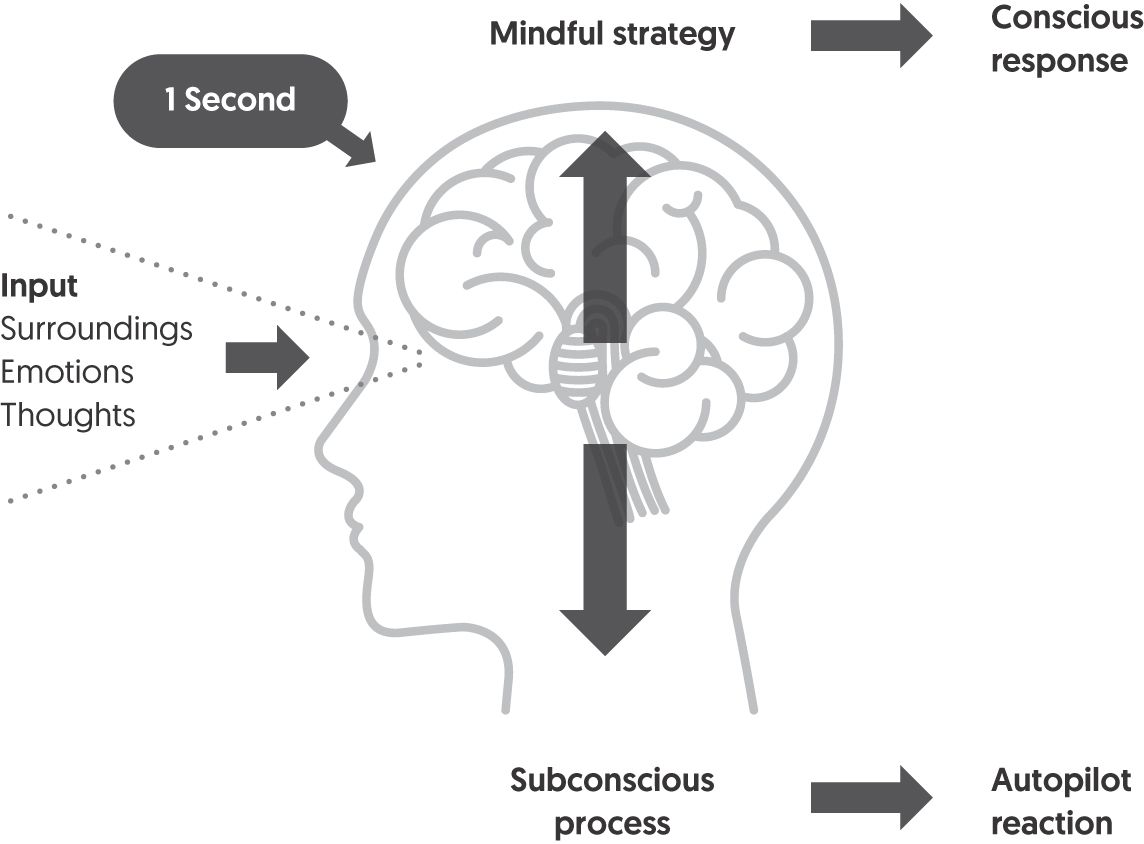

Jacob Larsen, vice president of The Finance Group, explained the power of getting one second ahead in a clear way. After he completed one of our ten-session mindfulness programs, we asked him what he had gained. His answer: “One second.” He explained that mindfulness gave him a one-second gap between his thoughts and his actions, between his impulses and his reactions. And this gave him greater control over his decisions and his responses. In any given situation, he said, he could better manage himself—all because of a single second. In this way, mindfulness can provide the moment-to-moment awareness needed to make better choices and take more productive action, as figure 2-1 illustrates.

FIGURE 2-1

The one-second mental gap

One second can be the difference between making a good or bad decision. It’s the difference between saying the words that motivate an employee and the words that disengage him or her. A second is the difference between lashing out at someone for an error or turning an unintentional mistake into a learning moment. A second matters. Especially for you as a leader.

Mindfulness training—and utilizing this one-second mental pause—is what helped Maura McCaffrey, whom we met earlier in this chapter, control her passion-bias. Through mindfulness training, she was able to become aware of the initial signs of her passion-bias and pause before reacting. With this pause, Maura began replacing her passion-bias with inclusiveness. After a little practice, it became natural for her to get buy-in from the group instead of forcing her own agenda.

Our survey results found that leaders at the highest levels tend to have better self-awareness than leaders further down the hierarchy. This could be because stronger self-awareness accelerates the promotion process or because, like Maura, we’re nudged toward enhancing our self-awareness as our leadership responsibility increases.

Take a moment to consider which automatic behaviors you have that sometimes hinder your leadership. What interferes with your team member’s feelings of engagement? What decreases the willingness of others to take your lead? What makes people feel insecure or disregarded? Ask yourself these questions from time to time to gradually increase your self-awareness and spur changes in your automatic reactions and responses. Doing so will not only make you a more effective leader, it will also help you better understand, align with, and act on your own personal values.

Calibrate Your Value Compass

In competitive business environments, it can be tempting to compromise our core values. The history of business is littered with leaders who have caused scandals, destroyed companies, wrecked economies, or ruined the lives of thousands of people because they strayed from a strong moral basis. Just think of companies like Enron, WorldCom, or Tyco. Or consider the 2008 financial crisis, BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and Volkswagen’s emissions fraud. These are just a few more recent examples of a broader trend. A national business ethics survey done by the Ethics Resource Center found that of the US workforce, 41 percent of workers have observed unethical leadership behavior in the previous twelve months, and 10 percent felt organizational pressure to compromise ethical standards.15

It’s easy to look at these cases, feel righteous indignation, and label the responsible leaders as evil. But it’s not that straightforward. Few people truly want to hurt others. According to extensive neurological and social science research, we’re genuinely good beings with positive intentions. We all want to contribute to the well-being of others.16 Some studies find that one of the only consistent neurological traits across cultures and races is that we are predisposed to kindness and altruism.17 Other studies indicate the general human impulse is to help and support others in need.18 We are truly good beings.

But if we are genuinely good beings with good intensions, why do we witness corporate leadership scandals one after another? Because intense pressure to increase revenue or make the quarterly numbers can erode our sense of self-awareness, which can lead to letting our values slip.

The rise of technology has also contributed to the weakening of our value compasses. With the rise in distractions, it has become increasingly difficult to keep our values in mind, simply because our mind is so busy with ever-increasing flow of information. With a heightened level of self-awareness, however, we’re better able to identify, acknowledge, and communicate our values. These values can help us navigate ourselves, our people, and our organizations in a more ethical manner and align our actions with what we want to offer to the world. In this way, awareness of our values becomes a compass, indicating instances when our choices don’t align with our ethical and moral standards. This, in turn, keeps us from cutting corners and helps us sleep better at night.

Thomas, an IT director we worked with at a global pharmaceutical company, shared a story with us about how he once found himself in an ethical dilemma. Two vendors were bidding on a major contract he was overseeing. One offer was slightly better than the other, but the vendor of the lesser offer had subtly offered a kickback to sweeten the deal. Pressured by a tight timeline, Thomas struggled with his decision for most of a day, constantly changing his mind.

To clear his head, he decided to do a few minutes of mindfulness practice, hoping to find clarity. As his mind calmed and he gained an increased level of awareness, his value compass clicked into action, pointing him in the right direction. While the kickback was attractive, he knew it was wrong to take it. He chose the other offer instead.

Reflecting on the dilemma, Thomas acknowledged that if this had been presented as a classroom ethics simulation, he never would have considered the offer with the kickback. But, as he explained, “With the complexity of the deal and the intense pressure to make a decision, it was hard to focus on the idea of right and wrong. Sometimes in business, with all the pressure, decisions don’t seem so clear-cut.”

Thomas’s experience is not unusual. Research has found that mindfulness practice enhances our ethical decision making.19 But if we lack the self-awareness necessary to have a strong value compass, we have a much greater chance of making the wrong choice or doing the wrong thing. This is especially true in morally ambiguous circumstances or high-stakes situations. And in the end—regardless of money or success, regardless of stature or fame—making unjust decisions or taking unethical actions will have a detrimental impact on our sense of self. And ultimately, it will negatively impact our happiness.

True Happiness—It’s Not What You Think

Self-awareness helps us answer one of life’s big questions, one that is foundational for leading our people: What makes us truly happy? This question should be front and center for any leader. Being self-aware of what constitutes true happiness helps in better leading people and tapping into what really drives them. True happiness bolsters feelings of fulfillment, engagement, and commitment. Because of this, it’s time for the practice and science of true happiness to enter basic leadership knowledge.

Take a moment to consider the following question: How often do you wake up in the morning wishing for a stressful day?

Now ask yourself another question: How often do you have a stressful day?

The point is, we humans do a great job of messing things up for ourselves. We hope to have great lives. We desire lives with few worries, with harmonious relationships, with balance and joy. Lives with fun and meaning. And in our developed world, we have the means to make this happen. We have advanced systems of education. We have state-of-the-art health care. We have enormous financial means. We have plentiful food. We have safe environments. We have resources and amenities that our ancestors could only dream of. Yet we manage to fall short of creating deeply meaningful, satisfying, and joyful lives.

What’s wrong with us?

We’ll get to the answer in a moment. First, on a scale from 1 to 10, how important is it for you to be happy, fulfilled, and satisfied with your life? Close your eyes and take a moment to consider the question. Don’t feel a need to come up with an answer. That’s not the point. Instead this should be a question you occasionally reflect on throughout your life. Now consider: Is your happiness more important than your professional achievements? Is your happiness more important than your wealth? Again, don’t feel a need to come up with rushed answers. These are questions for thoughtful reflection.

Frankly, we as humans have one go at a good life—and it’s a short one. Our childhood sometimes feels like yesterday. In thirty or fifty years, we may look back on today as yesterday, and our lives will almost be over. Life passes quickly. Think about how many people around the world went to bed last night, just like yourself, expecting to wake up this morning to another day in their lives—to another go at being happy. But instead, they didn’t wake up. They passed away in their sleep. Their chance at a day of happiness was lost forever. The difference between being alive or not exists in a flash, in a brief moment of transition. And we never know when that moment will arrive.

Having a happy life should be important. If we exit life without having tasted true happiness, without having experienced meaning and fulfillment, then what did we do? We missed the one chance we had.

We Don’t Know How to Be Happy

Now the answer to the earlier question: What’s wrong with us? Why do we fall short of being happy when we have so much? Quite simply, because we don’t know how to be happy.

From a leader’s perspective, understanding happiness and its roots permits us to create more meaning, purpose, and fulfillment for our people. This in turn can unlock great productivity. But as leaders—and as humans—we’re generally mistaken about happiness. It’s like we’re chasing it blindfolded. The things we generally look to for happiness don’t actually provide it. Research conducted at places like the London School of Economics and Political Science, Harvard Business School, and leading neuro research centers around the world and brought together by the United Nations in its annual World Happiness Report shows us our biases about happiness. We’re generally mistaken about happiness in two ways: (1) We believe happiness comes from the outside, and (2) We mistake pleasure for happiness.20

You Can’t Buy Happiness

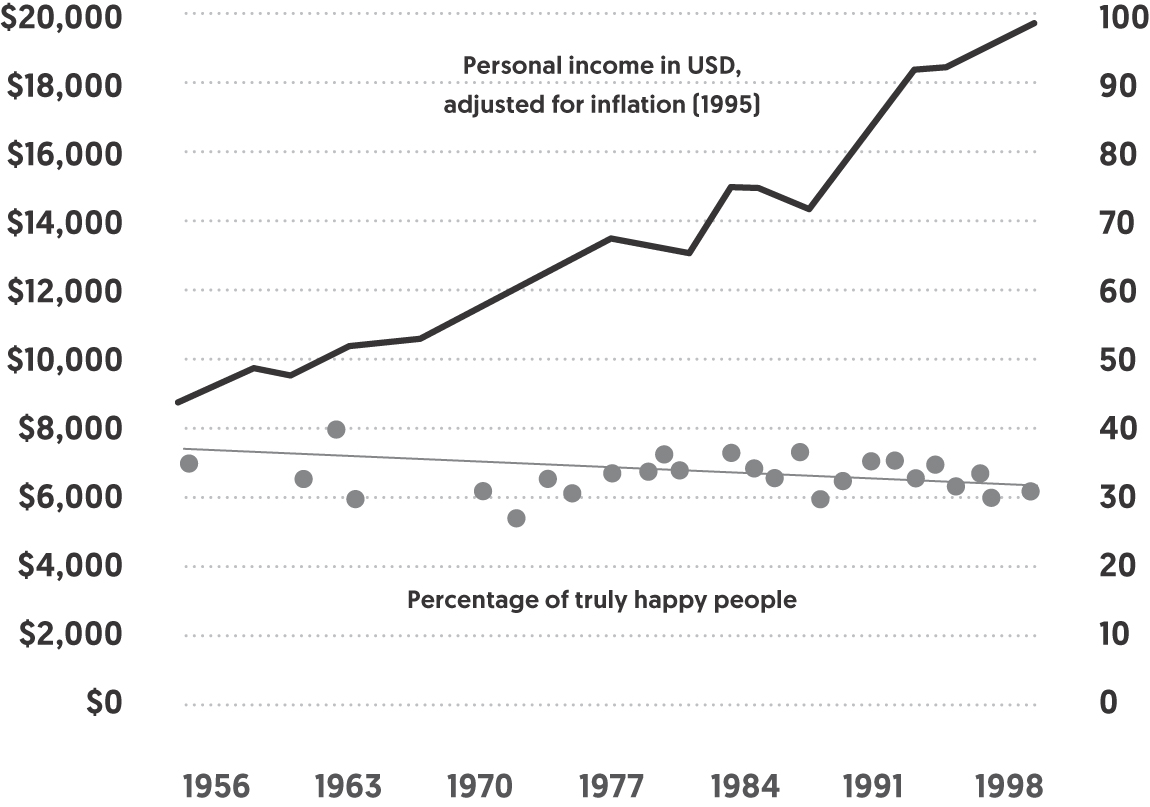

Major research studies show conclusively that true happiness doesn’t come from external sources. This is particularly true of external factors like money (see figure 2-2). For more than fifty years, researchers have looked at the correlation between happiness and wealth in the United States and other countries. Wealth has more than doubled, but the happiness level has decreased.

FIGURE 2-2

Income and happiness

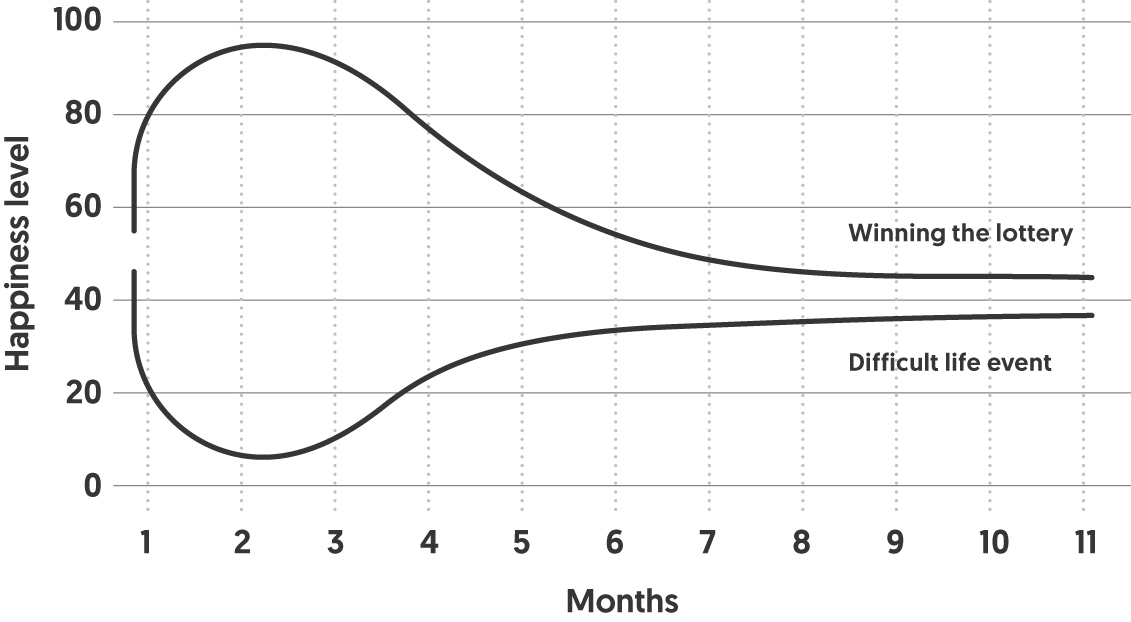

A separate study found that winning the lottery increased participants’ mood significantly, but after a while they returned to their normal baseline of happiness. Another study showed that while experiencing difficult situations, such as a job loss or major illness, participants’ happiness decreased significantly. But eventually, they also returned to their original baseline.21 In each of these instances, outside events—gaining wealth, winning the lottery, or losing a job—had a short-term effect on happiness but didn’t influence people’s long-term sense of happiness (see figure 2-3).

FIGURE 2-3

Happiness and life events

The message? External events and experiences do not create true happiness. Nor do difficult events and experiences create lasting unhappiness. This should be considered great news. It means that we as individuals can be in control of our own happiness. We may not get the desired promotion, the fancy car, or the magnificent house, but our happiness is not dependent on those types of things. It doesn’t depend on our status or wealth.

But our happiness does depend on the wealth of our neighbor. Consider the following two scenarios:

You live a life in which you earn $50,000 a year while other people get $25,000 a year.

You live a life in which you earn $100,000 a year while other people get $250,000 a year.

Which of these two scenarios would you prefer?

A joint study by researchers from the University of Miami and the Harvard School of Public Health found that the majority preferred the first option.22 This illustrates a paradoxical fact: when people become richer compared with other people, they feel happier. But when whole societies become richer, they don’t. Our happiness is relative to the wealth of our neighbors. Again, happiness does not come from the outside, but from how we relate to what we have. Happiness is an inner state deeply influenced by how we relate to what others have.

Pleasure Isn’t Happiness

We generally equate pleasure with happiness. We think that if we get enough pleasure, we’ll be happy. But we’re wrong. The two experiences are completely different.

In a way, pleasure is pure chemistry. When we get or do something we like—a promotion, praise, a new car—dopamine is released in our brain, giving us a sense of pleasure. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that helps control the brain’s reward and pleasure centers. It enables us not only to see rewards but also to take action to move toward them. However, dopamine can lead to addiction.23 The more pleasure we allow ourselves, the more we risk becoming addicted to it. The final result is a constant rat race in which we’re continually looking for that next rush of dopamine. Pleasure is a momentary experience that quickly fades as the neurochemicals subside.

True Happiness Is …

True happiness, in contrast, can’t be so easily located or pinpointed in the brain. It’s not in a specific region, and it can’t be found in a single hormone, neurotransmitter, or molecule. True happiness is an experience of fulfillment and of lasting well-being. True happiness is a long-term experience of a meaningful, purposeful, and positive life. It’s a deeply felt existential experience that can be maintained irrespective of the ups and downs of life, not a fleeting sense of gratification like pleasure.

We’re chasing pleasure in new business successes, more praise, and better pay, hoping it will make us happy. But it doesn’t. It just puts us on the treadmill of wanting more and more. This is not to say pleasure is wrong. Pleasure is great. It adds flavor to life. But pleasure is like eating honey from the blade of a knife. It tastes great, but if we’re not careful, we may hurt ourselves by craving more.

And never mistake it for happiness.

Take a moment to consider how these facts about true happiness might inform your leadership. Are there things you could do differently to help your people be happier and more engaged? Just think about this for a few moments. We’ll dive into these questions in more detail throughout the book.

Awareness Training

Mindfulness training helps you increase your self-awareness and thereby become more aware of what makes you truly happy. It helps you avoid your compulsive reactions and replace them with more useful behaviors. And it helps you stay true to your values. These are foundational skills for effective leadership, for being authentic, and for increasing team engagement.

But awareness training does more than that. The more time you spend training your awareness, the more you’ll come to fully appreciate that you are not your thoughts. Your thoughts are not you. The training helps you create a healthy and realistic distance from your mental activities. You start to observe your thoughts as fleeting events that have no real substance or importance. They’re just like clouds in the sky: they come and go. And they only have an impact on you if you allow them to. So many of our thoughts and feelings spark emotions or action. But really, many of them are random and insubstantial. We don’t need to react to them. We can simply let them be.

Bring this insight to how you perceive yourself, and you will be more at ease. Bring this insight to how you perceive others, and you will find it easier to lead them. Bring this insight to how you lead your organization, and you will find that you need to exert much less effort and control. As much as we like to think of ourselves as important because we are leaders, a realistic, self-aware, hard look will show that we are less important than we think. And the most appropriate response to that is to develop a realistic, selfless view of ourselves, as we explore in chapter 4.

The mental strength and freedom you develop through awareness training cannot be overstated. Through it, you come to know yourself in the moment, to know what you think, what you feel, and what is important to you (see “Training for Mindful Awareness”).

This practice, and the rest of the practices in this book are all recorded in a guided training app designed for this book. See appendix A for information.

Quick Tips and Reflections

Commit to practicing ten minutes of mindful awareness training on a regular basis as recommended in the app.

Commit to practicing ten minutes of mindful awareness training on a regular basis as recommended in the app. Identify one autopilot behavior you would like to change; set an intention to notice when the old behavior arises, pause, and chose a new response.

Identify one autopilot behavior you would like to change; set an intention to notice when the old behavior arises, pause, and chose a new response. Write down the values that are most important to you in your work life and as a leader; consider when these might be challenged and how you will respond.

Write down the values that are most important to you in your work life and as a leader; consider when these might be challenged and how you will respond. Consider what the difference between “pleasure” and “happiness” means for you and what insights this might have for how you lead yourself.

Consider what the difference between “pleasure” and “happiness” means for you and what insights this might have for how you lead yourself. Commit to one thing you will start, stop, or continue doing to increase genuine happiness.

Commit to one thing you will start, stop, or continue doing to increase genuine happiness.