9

Compassionate Leadership

In 2016, John Stumpf, now the former CEO of Wells Fargo, was called before Congress to explain a massive scandal. For more than four hours, Stumpf fielded a range of question about why the $1.8 trillion bank he led had set up 2 million false accounts, and, after it was discovered, fired fifty-three hundred employees as a way of redirecting the blame. The recordings of the hearing are a shocking, but illustrative case study of how leaders are at a risk of being corrupted by power.

We’ve already mentioned how power statistically makes leaders less considerate and more rude and unethical. The studies done in this field by researchers like University of California, Berkeley, professor Dacher Keltner are conclusive.1 But even more worrisome is that neuroscience seems to find that power, if not managed well, structurally changes the brain, leaving leaders with a deficit of empathy and an inability to put themselves in others’ shoes.

Stumpf’s appearance before Congress shows a man who had made it to the top of the world’s most valuable bank—and who has been left with an utter lack of ability to have compassion for other people. Even though his actions caused fifty-three hundred people to lose their jobs, he seemed incapable of acknowledging their pain. Yes, he apologized. But he didn’t seem remorseful. Rather, he seemed a little taken aback by the whole thing, as if he really didn’t understand what all the fuss was about.

The behavior of John Stumpf can be explained through the research of neuroscientist Sukhvinder Obhi, from McMaster University in Canada. In his study, Obhi put people with various levels of power under a transcranial-magnetic-stimulation machine to measure their mirror-neurological activity—the neurological function that indicates the ability to understand and associate with others.2 Interestingly, he found that power impairs our mirror-neurological activity. In other words, power dismantles our ability to see and understand others’ emotions and perspectives. Obhi concluded, “Anecdotes abound about the worker on the shop floor whose boss seems oblivious to his existence, or the junior sales associate whose regional manager never remembers her name and seems to look straight through her in meetings. Perhaps the pattern of activity within the motor resonance system that we observed in the present study can begin to explain how these occurrences take place and, more generally, can shed light on the tendency for the powerful to neglect the powerless.”3 Power, even on a neurological level, disconnects us from the world and leaves us in our own bubble.

In 2009, the British neurologist and parliamentarian David Owen published an article in Brain titled “Hubris Syndrome: An Acquired Personality Disorder?” that described the same issue. Owen defined the hubris syndrome as a “disorder of the possession of power, particularly power which has been associated with overwhelming success, held for a period of years.”4

One CEO we interviewed was very open about this problem. For more than a decade, he had been the CEO of a large global consumer goods brand. During that time, he found that his job had impaired his empathy. The constant pressure, the heady activity of dictating a strategy, and the need to make tough decisions with tough implications for others had made him unconsciously pull back from emotional involvement. He noticed it in relation to his colleagues, friends, and even his children. Empathy used to be a dominant trait of his personality. He would instinctually know how others felt and naturally demonstrate concern for their feelings. But in recent years, he had noticed how empathy was simply not part of his thinking or behavior. He was matter-of-fact about it but also remorseful.

Through our interviews, we heard variations of this time and again. It’s not that power makes anybody want to have less empathy. It simply results from the mental mechanics of taking on great responsibility and pressure, which can rewire our brain to disconnect from caring about other human beings. But it does not have to be this way. It shouldn’t be this way. Such rewiring can be avoided—and it can also be reversed. Compassion is the way.

By developing and training our compassion, we can counter the empathetic loss that results from holding power. But equally important, compassion is the key that enables truly human connections with our people. This leads to opportunities for people to experience a deeper sense of meaning, contributing to their happiness.

Of the over one thousand leaders we surveyed, 91 percent said that compassion is very important for leadership, and 80 percent would like to enhance their compassion but do not know how. Compassion is clearly a hugely overlooked skill in leadership training.

This chapter explores the qualities of compassion, how compassion and wisdom go hand-in-hand, how you can become a more compassionate leader, and how to train your mind to increase compassion. Let’s start by diving in to a greater understanding of compassion.

Compassion in Leadership

Compassion is the ability to put oneself in others’ shoes and in doing so better understand their challenges and how best to help them. Compassion is the intent to contribute to the happiness and well-being of others. With the numerous challenges faced by today’s workforce, compassion has become increasingly important and recognized as a foundational aspect of leadership.

Historically, compassion was not promoted as a cornerstone leadership quality. Many viewed it as being a soft skill not well suited for leaders. Compassion, it was thought, made you appear weak and overly emotional.

Before jumping in to the more practical aspects of compassion, let’s first clarify a few misconceptions about the term. Compassion is hard, not soft and fuzzy. In tough business environments, compassion requires strength and courage. Compassion is an intention that does not necessarily change your actions; instead, it changes the way you conduct your actions. Just think of the difference between firing someone with compassion rather than out of frustration. One is constructive, the other may be experienced as cruel. And make no mistake, firing someone can be compassionate if it’s done with the intent to help the other person learn and flourish in their next job.

Research by Professor Shimul Melwani, from the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Fliegler Business School, found that compassionate leaders are perceived as stronger and better leaders.5 In other words, if you dare to be compassionate, you’ll appear stronger, have increased levels of engagement, and have more people willing to follow you.

When we as leaders value the happiness of our people, they feel appreciated. They feel respected. And this makes them feel truly connected and engaged. It’s no accident that organizations with more compassionate leaders have stronger connections between people, better collaboration, more trust, stronger commitment to the organization, and lower turnover.6

Simply put, compassion is core to effective leadership.

Qualities of Compassion

Compassion is a single word for the intention to benefit others. But in that intention lie four distinct qualities. Together, these four qualities make up the meaning behind the word compassion. The first quality is the wish for others to be happy. The second is the wish to alleviate the suffering of others. The third is the joy of seeing others succeed. And the fourth is the ability to see all others as of equal worth.

These four qualities are closely connected; they mutually enhance and support one another. The following sections explain the four qualities and show how they can be used in leading people and organizational strategy.

Wishing Others Happiness

Years ago, Narendra Mulani of Accenture discovered the unspoken truth relevant to any leader: All people are alike in that they want to be happy and avoid problems. Narendra realized that if he could help his people be happy, he would not only do the right thing but also help them meet their most basic desire. Narendra started viewing his global teams as an extended family. He made it his leadership responsibility to actively support them in finding more happiness. Through this approach, Narendra cultivated stronger loyalty, increased job retention, and improved performance.

Narendra initially struggled with the apparent mismatch between compassion and tough, but necessary, actions. But with time, he came to realize that tough feedback, as harsh as it seems, can be given with a clear motivation of being of benefit to the receiver. “To people, this is their life,” he explained to us. “You have to make the right decisions for the business, but you have to make sure that people understand the reasons. I’m not going to mince words. They need to hear it from me; they need to understand it and absorb it. I have to tell them the reasons why. But I also need to tell them what they need to work on, how they can improve, or point them in a better direction.” In this way, compassion is about the motivation behind the action. Difficult feedback can be intended to be helpful and constructive to a person, when offered with compassion, or it can be intended to belittle or devalue a person, when offered in anger or spite.

When we develop a healthy, positive motivation for what we do, it changes our actions and behaviors. Narendra learned that motivation can play a significant role even when tackling a situation as difficult as letting people go. With compassion as his motivation, the dynamic of the conversation changed, both for himself and the person he was letting go. And most often, despite the difficulty of the conversation, compassion helped him attain better results. Narendra found this realization also applied to his clients: recognizing his clients’ desire to be successful and happy motivated him to be present with compassion. As a result, he became better at listening and understanding their needs, which helped him create better solutions. He now makes a habit of pausing before a meeting and asking himself what would make the individual client happy and truly benefit his or her organization. Instead of checking incoming texts or emails, he takes a moment to ask himself the following question: How can I be of benefit to make this person and organization successful and happy?

When did you last ask yourself how you could bring happiness to the people you lead or the clients you serve? How do you think it would change your interactions with them?

Wishing to Alleviate Suffering

The second characteristic of compassion is the wish to alleviate the suffering of others. Balancing the care of the individual with the care of the organization is a difficult part of leadership: the two goals don’t always go hand in hand. And without care, they may remain diametrically opposed. As part of the job, you have to tell people when they aren’t doing a good job. You have to let go of people to serve the larger objectives. Sometimes people are sacrificed to further the advancement of the organization.

In tough times, like large-scale layoffs, leaders risk growing numb to the individual’s suffering. When the 2008 financial crisis hit US accounting firm Moss Adams, then COO Chris Schmidt (now CEO) faced a challenge. Either the firm would make significant cuts, or the firm would risk financial failure. The decision was clear, though difficult to make. As Chris explained to us, the question he and his partners had to ask themselves was: “How can we do this in a way that inflicts as little pain as possible on the people who’ll leave, as well as the people who’ll stay?” As a firm, they offered generous severance packages and job replacement support. This compassionate approach allowed Chris to stay more humane, in touch with himself, and more present and authentic with his people.

When you make decisions that adversely impact others, how do you feel about it? The next time it happens, try to develop a compassionate attitude and intention toward the people involved. Then notice how it changes the dynamics of the experience.

Enjoying Others’ Success

The joy of celebrating the success of others is an invaluable leadership quality. Yet despite our best intentions, our ego often gets in the way of celebrating the achievements of others. But leaders can’t survive on their own—they can’t count on having the best ideas or strategies all on their own. They need collaboration. They need teamwork. To get the best out of others, leaders must develop a genuine motivation to support and celebrate the success of their people.

Marriott has embedded this motivation and practice into every element of their culture. At Marriott, there are no employees, only associates—over 400,000 of them. Career progression is a strong focus at Marriott. Many top executives and property managers started as waiters or front desk trainees. There is an elaborate system for mentoring, supporting, and training people for promotions. Marriott truly wants to see their people succeed in work and in life. Because of this support, Marriott has made Fortune’s list of the “Best Companies to Work For” every year since the list was created.

Marriott CEO Arne Sorenson spends about two hundred days a year on the road, visiting associates at hotels. He doesn’t just appear at a brief town hall meeting, but walks around and meets associates at the front desk, in the kitchen, or on the guest room floors. His objective is to listen to their thoughts; to understand their work, hear their concerns, and laud their successes. Marriott has a simple business philosophy: If we care for our associates, they will care for our guests, and the business will take care of itself.

When it comes to compassion, Arne doesn’t just talk the talk; he follows through with action. After 9/11, when the global travel industry plummeted and Marriott went from a 75 percent to a 5 percent occupancy rate, he waived the thirty-hours-per-week requirement for benefits and health coverage. This lessened the worries of Marriott associates and allowed them to focus on their jobs rather than fearing for the future. Arne sees this culture as critical to the company’s overall strategy. The culture he and his leadership team have created drives loyalty, which drives retention, which drives better service, which drives customer experience, which drives revenue. Marriott’s internal data shows that properties that score higher in associate engagement have better financial results.

As in Marriott’s case, the wish to see others be successful is a strong and sound strategy. How do you think such a strategy would help you and your business if you took more joy in others’ success?

Seeing Others Equally

Mark Tercek, former managing director at Goldman Sachs and current CEO of The Nature Conservancy, sent shockwaves through the environmental world when he announced a partnership with Dow Chemical Company. Mark believes that when we’re passionate about ideas but faced with opposing forces, we often turn to aggression and rejection. “It’s really easy to vilify people or groups you see as being on the opposite side of an issue. It’s easy to see them as evil or morally compromised.” But this approach leads to polarization, a situation in which collaboration and communication are abandoned.

A core element of compassion includes the ability to see others as truly equal. It’s the realization that we are all alike in our desire to be happy and not suffer. With this understanding comes a lack of preference for one person to be happier than another. When you see everyone as equal, the ones who cause you problems are valued the same as the ones you love. This may seem like a big ask, but as a leader, it’s a fundamental quality to embrace. It means supporting diversity and inclusion and putting the organization’s needs before one’s own personal preferences.

Seeing others equally allows us to be open. It allows us to find common ground instead of fixating on opposing opinions. Mark found that seeing others equally enabled him to dismantle his own automatic rejection of organizations and people who seemed at odds with his beliefs or goals. It allowed him to seek common ground and be open for constructive collaboration. By embracing a partnership with one of the world’s largest chemical corporations, The Nature Conservancy has been able to impact that organization’s environmental agenda in profound ways.

Mark was accused of indifference and a lack of values. But seeing others equally is far from being indifferent. It comes from a clear mind and a clear comprehension of reality as it is. Fighting against the things we don’t like in life will only marginalize us.

By default, the human mind categorizes experiences into three buckets: things we like, things we dislike, and things we are neutral about. Out of liking comes craving and desire. Out of neutrality comes indifference. Out of disliking comes aversion and rejection. Seeing others equally dismantles this entire categorization scheme and allows us to make more objective and reasoned choices.

All four qualities of compassion are powerful and have clear applications to leadership. To better develop each quality, we’ve included training practices for each in appendix B. But before going further, here’s an important question to consider. Is compassion ever misplaced in leadership? We asked this question as we interviewed hundreds of executives, and the answer was clear. Compassion is always important. But with one caveat—it must be paired with wisdom and sound judgment.

Wise Compassion

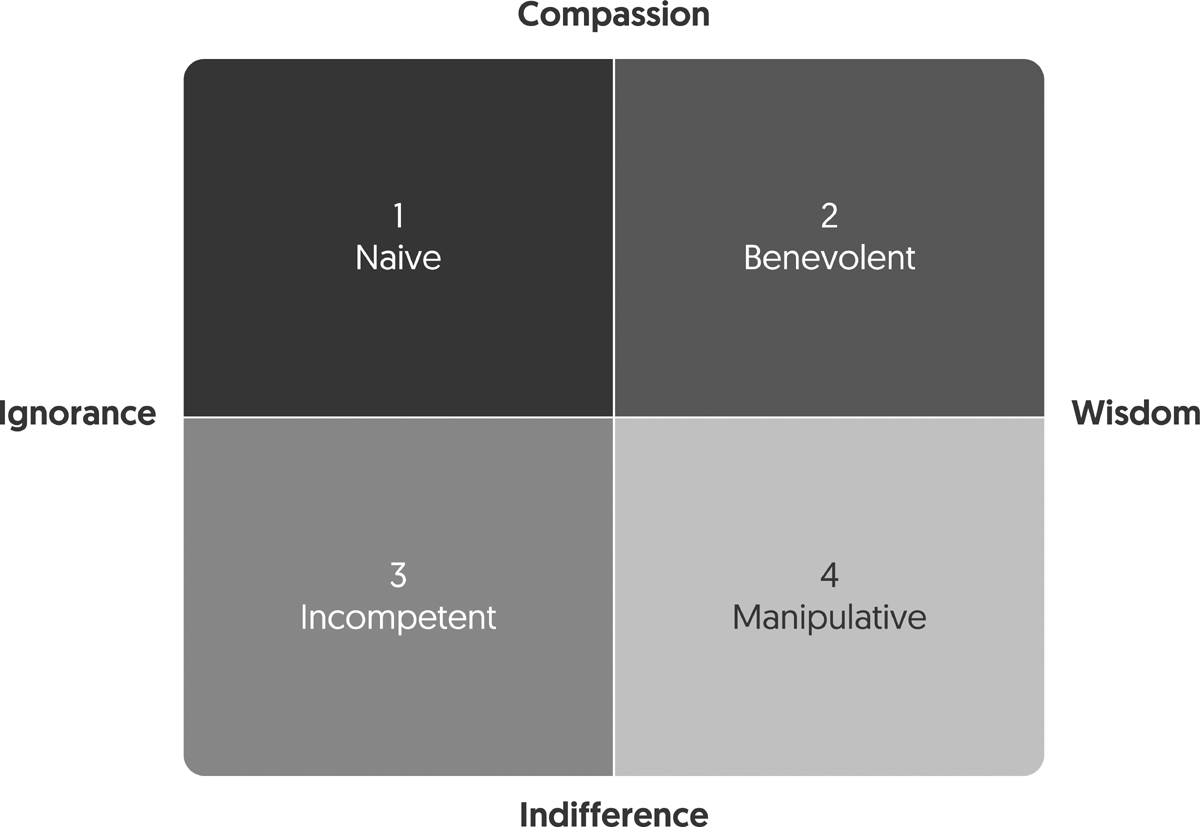

Compassion doesn’t mean you’re always trying to please people and give them what they want. As mentioned in chapter 1, to ensure we make sound decisions that benefit the bigger picture, compassion must be complemented by wisdom. Compassion and wisdom together can provide a clear leadership framework, as illustrated in the compassion matrix we introduced in chapter 1 (figure 9-1).

FIGURE 9-1

The compassion matrix

The top left quadrant in the matrix represents a state in which we have compassion but can’t discern the impacts of our actions. As a result, we risk doing disservice to the cause we intended to support. People and organizations solely focused on compassion risk acting out of naïveté and making well-intentioned mistakes.

The top right quadrant depicts the successful combination of compassion and wisdom. It is constructive compassion. We act to be of benefit to others, while closely discerning the impact of our actions. Leaders like the ones mentioned earlier in this chapter operate in this quadrant, balancing compassion with a skillful focus on organizational success.

A lack of compassion and wisdom falls in the bottom left quadrant. Without compassion, we’re indifferent. And without wisdom, we are unlikely to be able to get much done. Very few leaders and organizations are in this space, simply because success is close to impossible.

Similarly, the bottom right quadrant is also a dangerous place. The necessary skills and expertise for success are in place, but leaders in this quadrant lack wholesome intentions. Leaders operating in this space can be manipulative. They may be effective in delivering short-term results. In the long term, however, people will not follow their lead.

Take a moment to consider where in the matrix you would place yourself. Where would you place the leaders in your organization who are closest to you?

We’ve examined the qualities needed to be a compassionate leader and how to balance compassion with wisdom. Now let’s take a closer look at how to actually become a compassionate leader.

Become a Compassionate Leader

When we’re mindful, we remember to lead with compassion. When we have selflessness, we’re thinking less about ourselves and more about others. With mindfulness and selflessness as foundations, we can train to increase our level of spontaneous compassion. The more time we spend training our mind in compassion with the practice at the end of this chapter and those in appendix B, the more our brains will rewire for spontaneous compassion.

But even though compassion benefits us as leaders, benefits our people, and benefits our organizations, it’s not always easy to maintain. In the leadership survey we conducted for this book, we asked leaders what got in the way of being compassionate. The biggest culprits were workload, demands from others, and competing priorities. Stated another way, busyness makes it hard to have space for compassion in daily work. Other research corroborates our findings. A study from Brain Mind Institute, School of Life Sciences, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, showed that the more pressure we feel, the less we pay attention to the needs and emotions of others.7

In other words, when we get too busy, our attention goes to our head, rather than to our heart. The Chinese word for busyness illustrates this; it consists of two characters, one meaning “killing” and the other, “heart.” When we get too busy, we lose our heart. And in the lives of most leaders, this is a real challenge. But it’s one that can be overcome.

The Compassion Compass

A Chinese proverb says, “There is no way to compassion, compassion is the way.” Bringing compassion into any interaction you have and asking how you can be of benefit to others is the way to compassion. It is neuroplasticity in action.

Compassion is something we create by applying it to every interaction we have. In this way, it can become the compass that directs your intentions, attention, and actions. Whenever you engage with someone, ask yourself: “How can I be of benefit to this person?” Ask this of yourself every time you meet clients, stakeholders, colleagues, family, or friends. Let it be like a mantra that drives your intentions, moment by moment, in meeting after meeting.

John Chambers, former CEO of Cisco, knew that compassion was more than the right thing to do—it also had positive impact on his organization. He set up a system to ensure he was informed within forty-eight hours of any employee, anywhere in the world, who experienced a severe loss or illness. Once notified, he would personally write a letter and extend his support to that person. In this way, he instilled a top-down appreciation of the value of human care and compassion throughout the company. This type of compassion can be considered wise egoism.

Wise Egoism

Compassion is wise egoism because when we are kind to others, we are happier.8 Compassion is one of the most important contributors to our own well-being. It’s a true win-win no matter how you look at it. If you want others to be happy, show compassion. If you want to be happy, again, show compassion.

Compassion is also the antidote to negative mind states and in particular the emotion most destructive to our well-being and health—anger. Anger leads to an increased risk of cardiac events, an increased risk of serious illnesses, and, statistically, an increased death rate.9 Anger can be likened to holding a piece of burning coal in your hand. It hurts you, not the one you feel anger toward.

But dealing with anger can be tricky. We interviewed a senior director of a global professional services firm who shared a story of how anger trapped him while he was with an important client. The client, a head of state of a large country, started their first meeting by unconditionally criticizing the senior director’s firm. Instead of staying calm and constructive, he fell into the trap of righteous indignation—something he regrets to this day. The senior director ended up scolding the head of state and, as a result, lost the contract.

Though anger can feel good in the moment, it’s a trap. It narrows our perspective of reality and makes us focus single-mindedly on the cause of our anger. When this happens, we lose sight of the big picture. Our minds are literally distorted.10 Needless to say, this is not a good place from which to make important decisions.

Compassion is the direct antidote to anger and righteous indignation. The more you train to increase your compassion, the less space there will be for anger. Why? You can’t have both in mind at the same time.

Training Compassion

Compassion can be trained through a number of time-tested practices. Research has found that just a few minutes of practice a day will help your brain rewire for increased compassion and that with regular training, you can experience increased positive emotions, increased mindfulness, a stronger sense of purpose, and increased happiness.11 Compassion training has been shown to significantly alter the neural networks of our brain in such a way that we react to the suffering of others with spontaneous compassion, instead of distress and despair.12

Each of the four qualities of compassion can be trained individually. You will find the instructions in appendix B. But they can also be trained all at once with a single practice called giving and taking—Tonglen in Tibetan. The practice is simple, yet powerful, and has been practiced for thousands of years, passed from generation to generation, in China, India, Japan, and Tibet.

In short, the practice is about recalling a person you care for who is having a tough time and visualizing that you give compassion and take away their problems. You can do this exercise in a minute, or take as long as you like. Here is a short Tonglen practice for you to try. You can also use the app; see appendix A for more information.

You can do this practice as a sitting practice, taking a few minutes, or you can do it as a micro practice anywhere you are, in the office, at home, or on the road. When you enter a meeting or pass someone in the office, notice the expression on her or his face. Our faces carry any pain, hurt, and regret we might be experiencing. Look for it. And when you see it, breathe compassion into them in one outbreath and imagine that you remove their pain with your inbreath. Try it a few times, and see how this changes your state of mind and actions.

We all want to be happy. We all want to do good unto others. Every time you do this exercise, even if it’s just for a few seconds, you connect with your deepest and best human characteristics. You truly connect with yourself and with others.

Quick Tips and Reflections

Commit to practice compassion training as presented above or recommended in the Mind of the Leader app—see the appendix for information.

Commit to practice compassion training as presented above or recommended in the Mind of the Leader app—see the appendix for information. Make compassion the compass of your intentions for anyone you engage with; for any interaction, ask yourself how you can be of benefit to the person or people you are with.

Make compassion the compass of your intentions for anyone you engage with; for any interaction, ask yourself how you can be of benefit to the person or people you are with. Commit to one practical application of compassion in your leadership to increase genuine happiness, reduce unnecessary suffering, celebrate others’ success, or see others equally.

Commit to one practical application of compassion in your leadership to increase genuine happiness, reduce unnecessary suffering, celebrate others’ success, or see others equally. Consider where you are in the compassion matrix and where you would like to be; commit to one thing you can do to move in that direction.

Consider where you are in the compassion matrix and where you would like to be; commit to one thing you can do to move in that direction. Reflect on what wise egoism means for you and in what situations you would want to have this as your guidepost.

Reflect on what wise egoism means for you and in what situations you would want to have this as your guidepost.