3

Mindfully Lead Yourself

For today’s leaders, mindfulness—training the mind to be more focused and aware—is becoming a survival skill and a cornerstone of self-leadership. The pressure on leaders is increasing, as are the pace of change, the volume of information available, and the scale of complexity. A managing director of a global consulting firm told us that he had exhausted every tool on the market that promised to help him become more effective. He had applied all of the most popular time-management techniques. He had tried all the newest productivity software. He had incorporated the latest collaborative platforms. And yet he was still working as many hours as he possibly could. No additional apps could help, no more techniques could be applied, and no more minutes could be squeezed into the workday. He had run out of possible solutions.

His last resort: Train his mind.

With this realization, he became part of the global movement of leaders who are practicing mindfulness to increase awareness and improve focus.

As we discussed in chapter 2, mindful awareness helps us to switch off the autopilot and get in the driver’s seat of our mind. Mindful focus, which we explore in this chapter, helps us to be more effective and improve our well-being. In the first few sections of this chapter, we’ll examine the faculties of focus and provide strategies for more focused performance. We’ll then end the chapter with instructions on how to enhance focus through a guided mindfulness practice.

Survival of the Focused

Leaders—and people at work in general—have a problem. Our ability to focus and manage our minds is deteriorating. Research has found that we’re distracted from what we do 47 percent of the time.1 That’s an alarming number. Throughout any given day, we’re constantly thinking about things that happened in the past and things we need to do in the future. Meanwhile, we’ve lost focus on what’s happening right now. Although this research is a bit depressing, it also presents a massive potential for improved performance.

In our survey results, we found that 73 percent of leaders feel distracted from their current task either “some” or “most” of the time. We also found that 67 percent of leaders view their minds as cluttered, with lots of thoughts and a lack of clear priorities. As a result, 65 percent find that they fail to complete their most important tasks. When asked about the primary challenges to maintaining focus, the leaders answered that the biggest sources of distractions are the demands of other people (26 percent), competing priorities (25 percent), general distractions (13 percent), and workloads that are too big (12 percent). Not surprisingly, 96 percent of the leaders we surveyed said that enhanced focus would be valuable or extremely valuable.2

With the excessive number of distractions we face, attention deficit has become a norm in businesses.3 Thomas Davenport, author of The Attention Economy, wrote: “Understanding and managing attention is now the single most important determinant of business success.”4 The “attention economy” is an apt term for our current organizational environments. In today’s business world—with its seemingly endless distractions—our ability to focus is just as important as skills like financial analysis and time management. If there is one secret to effectiveness, said leadership pioneer Peter Drucker, it’s concentration.5 In our age of information overload, this is truer now than ever before.

Imagine a standard ten- to twelve-hour workday, with back-to-back meetings, a nonstop stream of emails, and the need to make good decisions in constantly shifting and complex contexts. The ability to apply calm and clear focus to the right tasks, at the right time, in the right way is what makes a leader exceptional. Even one second of misplaced focus is enough to miss a critical cue from a client during a tough negotiation.

Productivity has traditionally been measured in terms of time and competency: how much time we have for a task and our ability to solve it efficiently. But in an attention economy, focus is now such a scarce leadership resource that it overshadows time and competence. Imagine you spent thirty minutes on a task, occasionally checking your email and dealing with other distractions. The task itself should have only taken ten minutes, but you weren’t able to maintain a clear focus. That’s a significant loss in productivity. But the problem wasn’t mismanaged time—it was mismanaged focus.

In this light, a simple equation for productivity in the attention economy is Focus × Time × Competence = Productivity. Without focus, you will spend more time on a task and your productivity will be negatively impacted.

There also seems to be a direct correlation between people’s level of focus and the advancements they make in their companies. Of the thousands of leaders we’ve worked with over the years, the vast majority possess an above-average ability to focus. This is not to say that exceptional focus is a sure way to the top. But certainly, without focus, career success will be much more difficult to attain. For aspiring leaders, focus should be a daily mantra.

Through our research and fieldwork, we’ve come to a clear conclusion: focus must be at the forefront of any—and all—leadership training. The leaders we interviewed for this book all emphasized their need to cultivate and protect their focus amidst the relentless flow of details and distractions that assault their minds.

And yet, in our view, the business world is not focused enough on focus.

Consider these questions. When were you last exposed to focus training during a leadership development program? When did you last consider a calm, clear focus as part of an effective way to use your time? Just in the past week, how often have you experienced unfocused or distracted people in meetings?

Focus is rarely part of a training program or considered critical to effective time management. And many people are distracted during meetings, but they are rarely called out on it. This leads us to a great evolutionary irony: for most of human history, being prone to distraction ensured survival. Our alertness to sounds, smells, and movements that could indicate a threat was vital to our continued existence.

But today, the survival paradigm has reversed. In today’s distracted office environments, only the focused survive. And certainly, only the focused excel. All of the C-suite executives we interviewed shared stories of the importance of focus to survive and more importantly, to thrive. It was one of the qualities they considered as key to their success and valued for their people and their organization.

But it’s not easy to maintain focus. From a neurological perspective, we are wired for distractions. Part of our brain is devoted to constantly scanning our surroundings and reporting any new information of importance that may require our attention.6 The tendency to be distracted is deeply ingrained in older parts of the brain like the temporal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex. Test it for yourself. Stop reading and pay attention to your surroundings. Is your attention naturally directing itself toward movements and sounds?

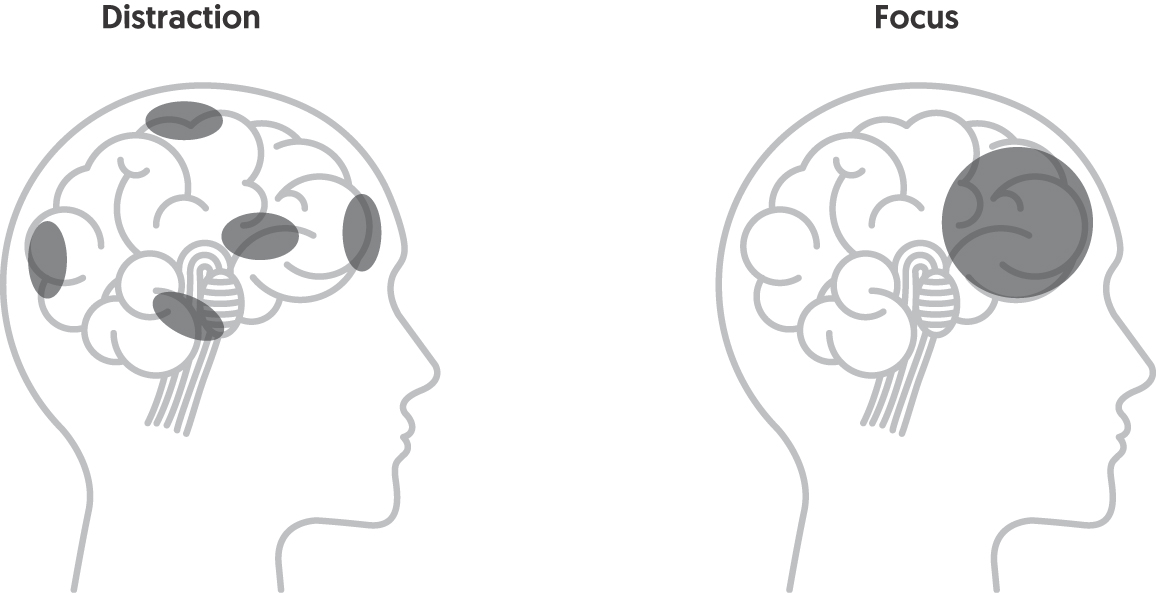

Distraction is the default setting of the human brain. Focus occurs mainly in the prefrontal cortex, the newest part of our brain, as illustrated in figure 3-1.

FIGURE 3-1

Where distraction and focus are found in the brain

The prefrontal cortex is also the home of executive function, which is our ability to deliberately choose our actions and behavior.7 When we are able to operate more out of this part of our brain, we have greater ability to minimize the noise from our wandering mind, are more focused on the task at hand, and can take more deliberate actions when engaging meaningfully with our people.

The Faculties of Focus

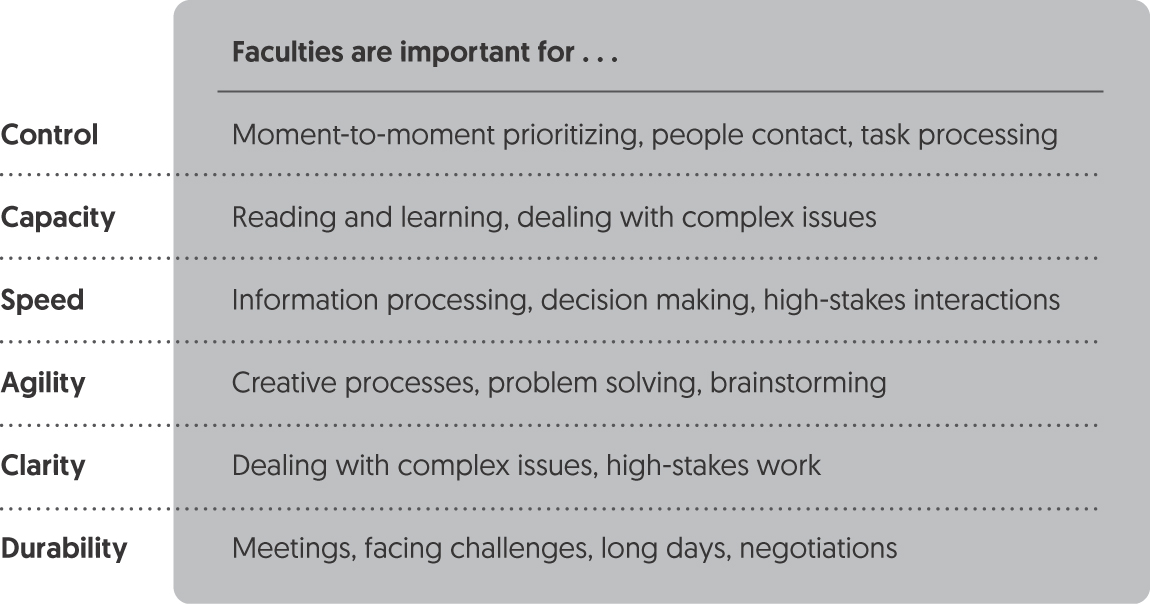

We’re all genetically predisposed for a certain baseline of focus. But we can improve on this baseline. For every moment we intentionally focus, our focus improves. Understanding the “anatomy” of focus can help us better develop it. Focus has six distinct faculties: control, capacity, speed, agility, clarity, and durability. The stronger each of these faculties is, the more effective our focus will be. Different situations require different faculties (see figure 3-2). And through well-guided mindfulness training, we can enhance them all.

FIGURE 3-2

The six faculties of focus

Let’s take a close look at each faculty.

Control

Controlled focus enables you to prioritize your attention and actions from moment to moment. It’s the opposite of distraction. It’s the quality of deliberately being attentive to one object or task. It’s the core of attention. As you’re reading this book, are you fully focused on reading? Or do other unrelated thoughts sneak into your mind?

In a study investigating the neurobiology of what happens when we become distracted, researchers found that during controlled focus, the prefrontal cortex becomes active to sustain attention.8 This neural synchronization is critical for getting things done. Without controlled focus, it’s virtually impossible to be effective. Without controlled focus when we’re with others, it’s difficult to make the connection necessary for meaningful communication. But with controlled, laserlike focus, astonishing accomplishments are possible.

For leaders today, there are more issues to deal with than there is time. Trying to focus on many important issues at the same time is a recipe for disaster. Leaders need to constantly focus and refocus, to give undivided attention on the most important issues moment to moment.

Capacity

Focus capacity enables you to absorb and process large volumes of information and cut through complexity. Focus capacity is the amount of data you can consciously be aware of at any given moment. It’s like your internet bandwidth, determining how much data you can download per second.

You can get a sense of your capacity right now: stop reading, close your eyes for a moment, then open them and look in front of you for one second, then close your eyes again. How many details can you recall from what you saw in that one second?

Researchers have been trying to measure focus capacity for years, with varying results. An average mind can comprehend between four and forty bits of conscious information per second.9 Our research shows that this is significantly less than the desired level needed for most leaders, as information overload is perceived as one of the five biggest challenges to their leadership effectiveness.

Loren Shuster, chief people officer at the LEGO Group, shared with us how mindfulness practice helps him absorb and retain many hundreds of pages of briefings before board meetings: “Doing a few moments of mindfulness before reading a briefing or report, calms and clears my mind. It creates the necessary bandwidth to absorb the details I know I’m about to read—and that I know I need to retain.” Loren added that by allowing himself a few more moments of mindfulness practice after reading, he is better able to synthesize and store information. “It’s been a revelation for me,” he told us. “I can recall the facts and figures I need, when I need them most—when the pressure is on.”

Speed

Your focus speed is the rate at which you process the flow of your experiences. Focus speed allows you to think on your feet and make fast decisions. Recall the last time you were in some kind of accident. Did time slow down, allowing you to vividly experience every split second? Of course, time didn’t actually slow down. It was instead your focus that sped up, providing you a close-up, seemingly slow-motion experience of the event. It’s as though a faster data processor kicked in.

Notice your focus speed right now as you read. How quickly are you able to get to the end of the sentence while still understanding the words in it?

Our focus speed varies, depending on how engaged we are, how complex a situation may be, or other environmental factors. During accidents, focus speed can be very high. But when we’ve imbibed alcohol, when we’re tired, or when we’re operating on autopilot, our focus speed is limited. Fighter pilots are known to have above-average focus speed. Imagine flying at more than a thousand miles per hour while having to navigate, keep track of your plane, and coordinate a precise flight path. This is daily work for a fighter pilot and calls for high focus speed.

Sue Gilchrist, regional managing partner for Asia and Australia, of the global law firm Herbert Smith Freehills, shared how she reads the underlying dynamics in client meetings. With mindfulness, she told us, her focus speed increases, whereby the speed of conversation seemingly slows down. “This allows me to pick up on more cues and implicit messages,” she asserted. “And the ability to see more of what is happening moment-to-moment in highly politicized or otherwise challenging environments is an invaluable asset, no matter what industry you’re in.”

Agility

Focus agility allows you to mentally switch from one task to another without lingering on the previous activity. This includes shifting from one meeting to the next or from writing an email to joining a conversation. In a hypercomplex world, focus agility allows you to mentally move efficiently among multiple complex contexts. It allows you to hold multiple opposing perspectives, values, and emotions and make more holistic decisions with less bias.

Focus agility, like the other faculties of focus, is impacted by internal and external factors. Tiredness, alcohol, mental busyness, and rapid task switching can decrease your focus agility and make you slower.

To test your focus agility, try this: As you read this sentence, abruptly shift your focus away from these words to something in your surroundings and focus on that object or image.

Did the switch happen swiftly or was there any mental lag? How quickly were you fully focused on the new object? Did any part of your focus still linger on the words you just read? If you’re not sure about your experience, try again; shift from one object to another object. Then observe the agility with which you transition your focus.

Focus agility should not be confused with multitasking. Extensive research has confirmed that humans are incapable of multitasking. We’ll explore multitasking in greater detail later in the chapter. For now, just understand that focus agility is the faculty that allows you to shift or switch between tasks—it is not the ability to perform multiple tasks at once.

Consider the following example from the CEO of Heineken, Jean-François van Boxmeer. As we entered the Heineken headquarters in Amsterdam to interview Jean-François, he was discussing the technical details of a complex acquisition with his legal counsel. In less than a second, however, his attention switched to the context of our interview. He was fully present, fully engaged. When we asked him how he switched his focus so quickly, he explained that his role does not allow for a lack of focus. “I can’t afford to be distracted. I must be on point. I have trained my focus while at work for fifteen years, moment-to-moment. I feel the brain is like a muscle, and I exercise it all the time. It’s about disciplined presence.” His day is packed with meetings from early morning until late evening; even meals are mostly organized as working meetings. In these kinds of extreme conditions, there’s little room for lingering on past activities. His well-trained mental agility makes this regimen possible.

Clarity

Focus clarity helps you register the details of your current task or object of attention. This means you experience whatever you focus on in high definition and maintain a distinct recollection of what has taken place in past moments.

Right now, how clear is your focus? Are you fully aware of what you’ve been reading? Or has reading made you a little drowsy? Take a moment to check in with yourself. How many facts can you recall from the last three pages?

Our research found that 90 percent of leaders believe that more reflection time would enhance their mental clarity. One way to visualize this is to think of the mind like a snow globe that gets shaken up throughout the day. Reflection time—as well as mindfulness practice and other activities—lets the snow settle, making everything easier to see and put into perspective.

James Doty, clinical professor of neurosurgery at Stanford University, describes how mindfulness training improves his focus clarity during surgery. This clarity provides him with a serene perception during the act of operating, including observations of the state of the patient, the state of the supporting operating staff, the granular details of the brain he’s operating on, and his own mental and physical state.

Durability

Focus durability is the span of time you can maintain a continuous state of focus on any given object or experience. A well-developed focus durability allows you to stay focused for hours without becoming distracted. But in an age of major technology distractions, our durability of focus is deteriorating.

How long do you think you can maintain focus on one object before becoming distracted? Try this quick test: Start a stopwatch or timer, focus on one object, stop when you first get distracted. Are you surprised by the result? If you managed less than ten seconds, don’t worry, that is normal. Having trained tens of thousands of people in mindfulness, we can testify that the majority of people last less than ten seconds on their first try.

Researchers have found a direct correlation between the heavy consumption of multiple forms of media—for example, print, television, phone calls, texts, video games—and shrinkage in our prefrontal cortex, the home of executive function.10 In other words, the more we allow ourselves to be inundated with information and distractions, the less brain capacity we have to maintain focus. But remember, thanks to neuroplasticity, with mindfulness training you can improve your focus durability. Even after as little as eight weeks of daily mindfulness practice, your prefrontal cortex gets thicker as your ability to focus improves.11

The next section includes some strategies to help you strengthen the six faculties of focus. After reviewing these strategies, we’ll present a mindfulness practice specifically for improving focus.

Strategies for Focused Performance

Based on our research and fieldwork, four strategies are particularly effective for leaders when it comes to focused performance: understanding what impacts focus, avoiding multitasking, thwarting action addiction, and creating focus time.

Understand What Impacts Focus

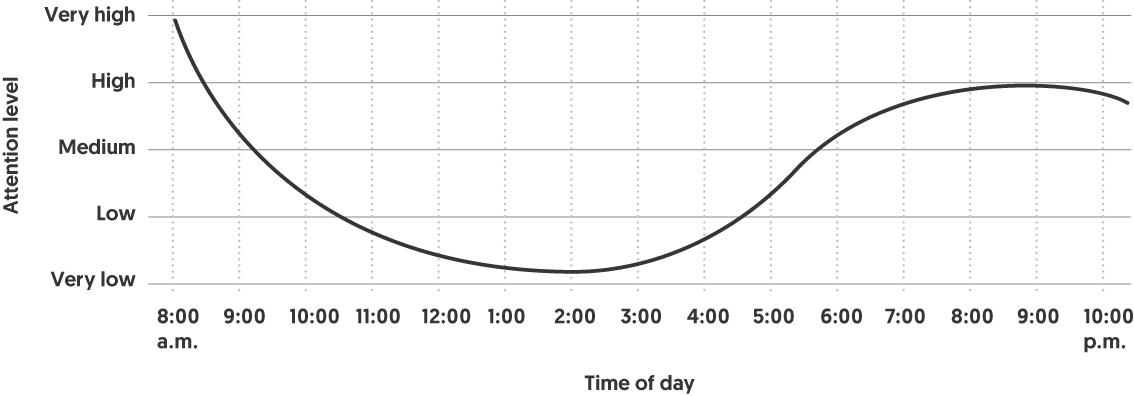

To maintain a strong focus throughout the day, it’s useful to know what impacts it, and how good your general focus is at different times of the day. Is your focus as strong at 8 a.m. as it is at 2 p.m.? How about at 10 p.m.? Consider how your focus is impacted by the time of the day, when you eat, what you eat, your mental state, and how many hours you slept.

For example, judges are trained to be neutral and objective in their legal rulings. From a statistical point of view, they should be making balanced, neutral rulings throughout the day. But studies have found that judges rule more favorably in the morning than in the afternoon. This means that it’s possible that a defendant may be sentenced to prison rather than set free if he or she enters the courtroom sometime after lunch.12

This pattern correlates directly with our research determining when leaders feel most focused. See the daily focus pattern of leaders in figure 3-3.

FIGURE 3-3

The daily focus pattern

With this pattern in mind, consider which activities you do at various times of the day. Make sure your most important activities are planned around the times when your focus is strongest. And plan to do more practical and active tasks during the hours when your focus is weaker.

Our focus and its six faculties are also impacted by other mental and physical factors, including sleep, emotions, and food. For an overview, see figure 3-4.

FIGURE 3-4

Factors that impact focus

Consider the mental factors first. Negative emotions generally decrease most of our faculties. Paul Ekman, a groundbreaking researcher in emotions from the University of California, San Francisco, described how difficult emotions create a refractory period that narrows our focus on the object of our emotion.13 In contrast, positive emotions generally have the opposite effect, opening up our focus to see the bigger picture.14

From a physical perspective, relaxation is a prerequisite for strong focus. Relaxation is the absence of unnecessary effort, of both mind and body. When we relax our body, our mind follows. When we relax our mind, we also relax our body. In this way, mind and body are linked. Also, if we care for our body with quality sleep, nutrition, and exercise, our focus is enhanced. Coffee, contrary to what many of us believe, is not useful for focus. The caffeine enhances wakefulness but scatters focus.15 And not surprisingly, alcohol is harmful in most aspects as well.

What other activities do you do that impact your focus, whether positively or negatively? You’re likely facing competing demands most of the time: people in need of your attention, urgent emails, and high-stakes decisions. The automatic response of the brain is to try to focus on them all at once. By default, the brain wants you to multitask. But multitasking kills your focus.

Stop Multitasking

Our ability to multitask is a myth. Most of us carry around the powerful illusion that we can pay attention to more than one thing at a time. We think we can drive a car while talking on the phone, participate in a meeting while checking emails, or engage in a conversation while writing a text message. To be clear, we can do many activities without paying attention; that is, without conscious thought. For example, we can walk and talk at the same time. Experienced drivers can handle many of the elements of driving, such as changing gears and turning the steering wheel, on autopilot.

But from a neurological perspective, we’re not capable of focusing attention on two things at the same time. Multitasking is really shift-tasking: shifting attention rapidly between two or more things. For a second, we’re aware of traffic; the next instant, we’re attending to the phone. Sometimes we switch so rapidly between tasks we have the illusion we’re paying attention to both at the same time, but in reality we’re not.

In the context of multitasking at work, researchers have found that when we multitask, we become “masters of everything that is irrelevant, we let ourselves be distracted by anything.”16 Perhaps you’ve experienced losing track of what you are doing even when you have a simple task and clear intentions. For example, imagine that you’re looking at LinkedIn for information about a person you’re considering for a job. Then you notice a link to an article that looks interesting. You hit that link and start reading and find a link to an interesting video on YouTube. An hour later, you catch yourself still watching videos and have completely lost track of what you started out to do. Sound familiar?

Studies have shown that multitasking lowers people’s job satisfaction, damages personal relationships, adversely affects memory, and negatively impacts health.17 Many of these studies have demonstrated that multitasking reduces effectiveness because it takes longer to complete tasks and leads to more mistakes. This is because when we switch our focus from one task to another, it takes time to make the shift. Depending on the complexity of the new task, that can take anywhere from a few seconds to several minutes. This phenomenon is called shift-time. Shift-time saps our mental energy and taxes our productivity.

In addition, researchers from Harvard Business School discovered that multitasking hinders creativity.18 After assessing nine thousand employees working on projects that required creative thinking, researchers found a notable drop in creative thinking among employees who multitasked and an increase in creativity among those who focused on one task at a time.

When we don’t multitask, when we stay focused on one thing at a time, we benefit. We also benefit from not getting trapped in activity.

Avoid Action Addiction

Action addiction is characterized by an uncontrollable urge to be doing something and a discomfort with being still. It includes behaviors like constantly checking emails, texts, news feeds, or social media. Action addiction keeps us busy and may help us complete many “tasks,” but activity is not the same as productivity.

One could argue that when we’re action addicts—when we constantly answer email, shoot off texts, or take phone calls—we get a lot done. Sadly, that’s not the case. In the 2002 Harvard Business Review article “Beware the Busy Manager,” researchers shared findings on managers’ ability to prioritize. After an in-depth study of leaders in companies like Sony, LG, and Lufthansa, they conclude: “Very few use their time as effectively as they could. They think they’re attending to pressing matters, but they’re really just spinning their wheels.”19 Another study looked at the priorities of more than 350,000 people and found that they spend an average of 41 percent of their time on low-level priorities.20 In other words, they’re doing lots of things but not getting the right things done.

We are so wired for doing things that a survey found that 83 percent of Americans spent no time relaxing or doing nothing in the past twenty-four hours.21 When did you last sit without doing anything? Try it out now. Put the book aside and do nothing for three minutes. Observe your reactions to it.

How did it go? Did you feel an urge to check your email, or do something else? If yes, you may be suffering from action addiction.

Action addiction is a very real condition most of us have to some degree, and the cause lies in our brain. When we complete a task, even the smallest insignificant task like sending an email, dopamine is released in the brain. This can make the task addictive. But dopamine is blind and does not distinguish between activity and productivity. This means we get a dopamine hit just for doing something—anything. And this makes us effective at doing a lot of things but not necessarily at doing the right things.

The obvious consequence of action addiction is that we’re constantly chasing short-term wins and losing sight of our bigger goals. When this happens, our ability to prioritize suffers and our performance diminishes. Because action addiction is a mental state, we can overcome it through the practice of mindfulness. Mindfulness training improves focus and impulse control. It provides you with the mental strength for observing, reflecting, and doing important things, rather than just doing a lot of things.22 In addition, we can carve out time for focus.

Create Focus Time

Our propensity to multitask and get caught in action addiction are increased with the continuous rise in and reliance on technology. But we have a choice in how we respond to technology. With a well-trained mind, we have a choice of what to focus on and the ability to avoid multitasking and action addiction. We also have the choice of planning our time and activities in a way that facilitates getting important things done.

Arne Sorenson, CEO of Marriott, plans uninterrupted hours of focused meetings with members of his team with no phone, computers, or other devices in the room. Jean-François van Boxmeer, CEO of Heineken blocks out a percentage of his time specifically for tackling important tasks. Dominic Barton, global managing partner of McKinsey & Company, takes a long run every day to process, reflect, and synthesize. In each case, these exceptionally busy leaders are putting aside specific blocks of time designed to increase their focus. For them, disciplined focus is a mantra for productivity. They understand that if they do not plan time to do focused work, they easily end up doing everything that is urgent and not what’s important.

Cal Newport’s book Deep Work describes the need and techniques for focused work for leaders.23 When we dedicate our full attention, pointedly and without distraction, to any task, we are more productive. We also experience a greater sense of fulfillment as well as a comforting sense of being in control. This experience carries over into the rest of the day, decreasing stress and increasing focus and calm.

Focus time often conflicts with an always-on organizational culture. Focus time therefore requires some principles, discipline, and preparation. To secure focus time, the following steps can be helpful:

Block out focus time on your calendar. Rather than prioritize what’s on your schedule, schedule your priorities.

Block out one hour—or more—every work day of the week, the month, and the year. Be disciplined about utilizing this hour for focus work. Schedules can change, but do what you can to avoid having other people claim your focus time for meetings.

Plan your time during the hours when you are most focused. Save email and other activities for times when your focus is lower.

Share the importance of focus time with your peers and colleagues. Make your closest associates allies in protecting your (and their) focus time.

As you start your focus time, define clear goals for how you will use it. Then stick to these goals. Don’t open your email (unless that is the goal of your focus time), don’t respond to texts, don’t participate in any other unfocused activities.

Eliminate distractions. Close your door or find a space where you will not be interrupted. Put your phone away. Keep your desk clean and free of any distractions.

The challenge is not only external distractions; internal distractions can be even stronger. Other issues may be pushing their way into your consciousness. Compartmentalize them. Right now, you’re doing more important things.

While you’re in your focus time, be disciplined. Be disciplined about staying focused, so that you get the most out of the time. Do not give in to a dopamine craving. As much as you may feel like checking email or messages, refrain from it.

All the above strategies have been demonstrated to be highly effective in enhancing performance and well-being. But as simple as they may sound, without having a well-trained, focused mind, they are challenging to implement. The true foundation of greater focus is a disciplined daily practice of mindfulness.

Mindful Focus Practice

Focus is the core of self-leadership. Without it, your mind is like a boat without a rudder. Training your focus through daily mindfulness practice will enhance your ability to be more focused during daily work. The following are instructions on how to do this (see “Training for Mindful Focus”). The practice has four primary instructions: A for anatomy, B for breath, C for counting, and D for distractions. For ease of practice, download the app that you can find in appendix A.

In an always-on, distracted world, we shift between tasks constantly. But focus is critical to us as leaders, to improve both our effectiveness and our productivity. With enhanced focus, our self-leadership is strengthened. All the tips and strategies presented in this chapter will help you strengthen your focus—and as a result, improve your outcomes. The next chapter builds on the foundation of focus by examining how selflessness—letting go of ego—is essential in leading yourself effectively.

Quick Tips and Reflections

Commit to practice mindful focus training on a regular basis, as recommended in the app (see appendix A for information).

Commit to practice mindful focus training on a regular basis, as recommended in the app (see appendix A for information). Take Harvard Business Review’s “Mindfulness Assessment” (https://hbr.org/2017/03/assessment-how-mindful-are-you) to assess your level of focus and awareness.

Take Harvard Business Review’s “Mindfulness Assessment” (https://hbr.org/2017/03/assessment-how-mindful-are-you) to assess your level of focus and awareness. Record what impacts your focus and how it changes throughout the day; make a commitment to change one thing to enhance your daily focus.

Record what impacts your focus and how it changes throughout the day; make a commitment to change one thing to enhance your daily focus. Commit to being more intentional about how you spend your time, and whatever you do, do it with a calm, clear, relaxed focus.

Commit to being more intentional about how you spend your time, and whatever you do, do it with a calm, clear, relaxed focus. Block focus time in your calendar and determine when and how you can mindfully “disconnect” to enhance openness and creativity.

Block focus time in your calendar and determine when and how you can mindfully “disconnect” to enhance openness and creativity.