How dull it is to pause, to make an end, to rust unburnished, not to shine in use! As though to breathe were life.

When Tennyson wrote Ulysses, he took up the story of Ulysses where Homer left off. He is now an older man who finds that the home and the love he longed for while sojourning are not enough for contentment in these years. A life of idleness became a burden. Tennyson's story is a shining articulation of what can happen in traditional retirement. Retirement today puts people on society's back burner and tells them they should be happy to be there—but many are not. Many of those in retirement want to "shine in use." Tennyson's conclusion in poetry was also reached by Freud in science—that is, love and work are essentials in human life.

To many, work is a dirty word they want cleansed from their lives. At the outset of a new discussion around work, allow me to offer my own definition of what I mean when I use the word work—a meaningful and productive engagement, paid or unpaid. The focus is on doing something you find meaningful and that society finds productive. For such activities, we can collect either a material or an emotional paycheck—or both. Whether it be for pay or volunteer, we all need to know we can be useful.

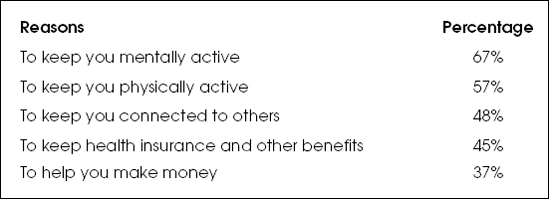

As many baby boomers enter their late 50s and 60s and realize they may be able to retire, they will have to grapple with the decision of whether they will be happy doing little work or doing no work. An informal survey conducted by BusinessWeek Online found that a high percentage of people are concerned that their skills won't be used to the fullest as they near and pass retirement. Following are some of their answers to the poll:

Do you agree that over-55 workers constitute a talent pool that too many companies leave untapped?

Very much—64 percent

Somewhat—27 percent

Are you concerned that your skills won't be used to their fullest as you approach retirement and after retirement?

Very much—27 percent

Somewhat—38 percent

Slightly—13 percent

If your current employer offered you the opportunity to continue working on a less-than-full-time basis as you approach retirement or afterward, would you be interested?

Very much—48 percent

Somewhat—30 percent

Slightly—8 percent

If a new employer offered you the same opportunity, would you be interested?

Very much—47 percent

Somewhat—30 percent

Are you concerned that without some kind of employment, your postretirement years would be lacking?

Very much—23 percent

Somewhat—29 percent

Slightly—21 percent

Bear in mind when looking at these numbers that they refer to people who are looking ahead to retirement. As we'll see later in this chapter, the illusion of a blissful workless retirement diminishes the closer one gets to actual retirement and all but evaporates once one actually tastes a few months of retirement life. Generally speaking, we are not a species that is engineered to be happy doing nothing.

Imagine your average day in retirement. You get out of bed at 10 AM and wander around the house in your pajamas drinking a cup of coffee. You then turn on Power Lunch on TV, grab a book, and go to the club for lunch and your 2:00 PM tee time. You come home after the round of golf for an evening of viewing sitcoms on television. How does this day sound to you? The people who feel imprisoned by their job impulsively say, "Yeah! That would work for me!" But the reality check is in contemplating this routine for the next 10,950 days of your life. If you were to retire at age 55, you've got another 30 years of your life to invest! The reality check is also asking what you're going to do on the days that it rains. I can't count the number of people I have met who reached this early retirement scenario by obsessing over investing their financial assets and gave little or no thought to how they would invest their chief asset—their life and energy. I have also met far too many retirees with little else to do than fret and obsess over their investments every waking day.

What is missing in this scenario? Let's add one more activity to this portrait and see what a difference it makes. You get out of bed at 7:00 AM and wander around the house in your pajamas drinking your coffee and contemplating your consulting work for the morning, which includes a conference call with a client at 11:00 AM. After that, your working day is over and you head out to the club. If it rains, you have hobby or charitable activities to occupy your afternoon. Could you endure a routine like this for the next 10,950 days of your life? By adding engaging work and activities to this portrait, we make it a much more inviting and desirable picture.

To eradicate work from our life is to deny a meaningful aspect of our life. It is a denial of our very soul. Our soul finds pleasure in meaningful labor and productivity. Booker T. Washington in Up from Slavery wrote: "Hard work should not be avoided but sought out because it is hard work that makes the soul honest." This he wrote when observing the impact on the quality of life that work-lessness wrought in the life of slaves who rejected work as evil. The bitter taste of slavery in their psyche caused many of them to avoid all work. Washington tried to show them that this view of work had led them into a new degradation of their own choosing. Is there an analogy here for those who have felt that workless retirement was the just solution for the years they spent "slaving" for a corporation they grew to despise? Is the workless state really a mirage that appears most enticing to the bitter and the burned out?

I had achieved my American dream when I retired early at age 55. I was the envy of my peers. I had worked hard and invested well. I had been motivated by visions of fairway days and beachfront nights in Florida. I would never answer to anyone again. It didn't take long before I began getting this eerie feeling on the first tee that I was too young and valuable to be wasting all my life energy on leisure. But I just kept pushing those thoughts back. 'This is your reward,' I told myself, 'you've got what everyone else wants.' I was beginning to get bored and was spending more and more time at the 19th hole. I was forming bad habits. My wife couldn't wait to see me go out the door each day. My true reality check came one day when I ran into an old colleague who was five years older than me and who was still working. He looked great. I was now 62 but I looked like I was 70. He didn't say anything but the look in his eyes when he first saw me gave it away. A life of nothing but leisure had led to my accelerated decline. No one had ever mentioned anything about this side of the early retirement story.

We are, I believe, coming to grips with the significance that work brings into our life. Rather than viewing retirement as a cold-turkey exit from the working world or a jump from the cliff of employment, we are beginning to view it as a transition or a segue. The transition ramp may be a gradual decline of hours spent on the job. It may be ramping up into free agency or another career. Why do so many retirees come back to work soon after they retire? Obviously, they miss the significant aspects that work brings into their life.

Why do almost 80 percent of us say we want to continue working in some way, shape, or form? Because we realize that for all that we give to our work, work gives something back to us. When we strip away the annoying personalities and the frustrating tasks that our current job offers, we realize that work can provide great intangible rewards to our mind and spirit; camaraderie; shared victories and disappointments; identity; the adrenaline rush of the chase; building something out of nothing; moving from a concept to a reality; the realization that our efforts have influenced or helped people and the world we live in; relationships; and a sense of accomplishment. These benefits should not be underrated when assessing the place of work in our life.

Our nation's evolving attitude toward work was revealed in a 2005 HSBC study entitled "The Future of Retirement in a World of Rising Life Expectancies." In this study, 93 percent of Americans state that they should be able to go on working at any age if they are still capable; 64 percent feel that retirement is a chance to write a whole new chapter in their lives (versus 23 percent who see retirement as a relaxation period); and 46 percent indicate a desire to move back and forth between work and leisure. Add to this the fact that 35 percent of the respondents in a Merrill Lynch/Dychtwald study stated unequivocally that they would never retire.

By an overwhelming majority, retirees have decided that the best reason to keep involved is the vitality, energy, and perspicacity that work arouses. They have recognized the enjoyment that work brings even if part of their motive is the need for money. The realization comes to the majority of retirees sooner or later that the choice to retire entirely from productive engagements is not a good one.

If your only reason for doing what you do Is to have enough money To no longer have to do it Then what will you do When you're done?

You may find That a big part of you Was in the doing And that an important part Is now undone.

A job may be finished But the piece of you That does the work Is never done.

It is difficult for people to separate who they are from what they do—and for a very good reason. For many, what they do is nothing more than a professional expression of who they are. For these people, retirement dates loom like a stayed execution date. They wonder, "What's in my retirement afterlife?" I have noted this to be especially true of professionals (lawyers, doctors, financial advisors, etc.) who have the kind of work that pulls daily on their intelligence, intuition, and experience. Will these brain/soul/spirit functions get the necessary unction from a game of golf and crossword puzzles? For those of us who prize the privilege of solving problems and puzzles, creating solutions, and tapping our mental fecundity, the answer is an emphatic NO!

I see the fizzle of suspected languishing in the eyes of these people as they move with apprehension toward this date of "extraction." There is a hint of hesitance in their voices and a trace of trepidation in their souls as they amble toward the cultural expectation of what they ought to do at age 62 or 65. But why should it be this way? I tell one preretiree after another, "Don't let anybody tell you when you are finished" and "As long as you have something to offer, offer something." Many of these people are afraid they are headed toward an all-or-nothing, cold-turkey retirement where they are forced to turn off important and fulfilling parts of who they are. This leftover foolishness is from another era—one that has been laid to rest in the Industrial Age graveyard.

It doesn't have to be 40-hour weeks and 50 weeks a year. You can work at any pace you choose—for whatever periods you choose.

Maybe it's time for white-collar professionals to start wearing hard hats to work because there is something precious and irreplaceable at work under those hats. What clearly pays these days is intellectual capital—what you know, how well you know it, street savvy, know-how, know-who, rainmaking relationships, contextual understanding, history, and strategic insight.

How do you turn all this off? And once you do, how do the businesses and institutions recover from the loss of such precious capital? It is what's between your ears that makes the world of business go around these days. Every institution, whether it's for profit or nonprofit, is like a lung needing oxygen—relying on the intellectual and experiential capital of its members. This sort of capital is not easily replaced and has worth in two ways: (1) it brings in money when you know how to get it done and who to work with; and (2) it pays your sense of personal esteem to exercise this capital on an ongoing basis.

Let's not lose sight of Maslow's Hierarchy here. The second-to-last step (before self-actualization) is esteem. Once we stop utilizing our intellectual capital, we are abandoning a source of esteem that has served us throughout our professional lives. What well will we tap esteem from next? I'll never forget the fellow who told me of being stopped on the street by a woman who asked him, "Didn't you used to be Dr. Jones?" He went from "Who's Who" to "Who's he?" in a heartbeat. (More on Maslow and how his theories relate to retirement is in Part Three.)

I feel good about myself when I read and think and philosophize. I feel good about my life when I write down my thoughts and give speeches that help people in their journeys. I feel good about who I am when a company calls and wants to hear my ideas on a given project or topic. If these activities and this flow of intellectual capital were removed from my life once and for all, I think I might go crazy and take familial hostages along with me. I don't believe I'm alone on this point either.

I don't think I can get this same effect from RV trips, three-hour morning coffees, or endless rounds of golf. Will I slow down some in later years and maybe adjust the pace a bit? Quite possibly. Maybe I'll occasionally take a month off instead of the sporadic week. There's a big difference between turning down the faucet and letting the pipes freeze.

I want the flow to continue from my mind and soul to the world I live in ... and back again. I believe that there are many others who desire this all-important flow of intellectual capital to help them stay plugged into the world in which they live and the person within. For those who have exercised intellect, imagination, and wits in their careers, this is an issue they cannot afford to ignore.

I had this conversation with my lawyer the other day. He's approaching that age where people think about retirement—and he doesn't like the idea at all. He seemed comforted to hear that someone agreed. Soon after, I had another conversation with a successful local financial advisor who also was bothered by the idea of being out of the flow with ideas and people—of which this business offers plenty. He just wants longer periods off and to know that the shop won't implode while he's away.

Recently, after speaking to a client gathering in California, I was approached by a man who looked to be in his early 50s. He was a gentleman who told me he had run a successful dental practice for years and was now just showing up "now and then" because he was busy with a number of other causes, including a real estate company, a benevolent association, regent at the local college, president of the International College of Dentists (and three other professional associations), chairman of the board of a local bank—and more!

This doctor also informed me that through the years he has returned to his home village in China to build a school, a modern water system, and a temple. Stunned at his productivity at such an age (I assumed 50ish), I asked him how old he was. "I'm 83," he informed me, "and I think I have a lot of good years left. I appreciate very much your message because I think many people have many more good years than they think, if they will just stay with it."

You could've knocked me over with a feather. This man at 83 had the skin of man in his 40s, the articulation of a talk-show host, the perspicacity and acuity of a surgeon at work, they energy of a dot-com marketing exec, and the unmistakable shine in the eye of a man who not only made his own way in the world but also set his own finish line as well. I walked away from that conversation with a new hero and role model for how I want to be in my 80s.

He is a retirementor: someone who is a master of his own destiny, refuses to accept society's norms for when the game is finished, and be enthused with the belief that while the aging process continues, being old is in their locus of control. I have an unusual and privileged vantage point on this issue as I travel throughout the country inspiring people to make their own rules and decisions, to think twice before they lay their talents on the campfire, and to move from aging to s-aging (more on s-aging in Chapter 15). After my presentation, the best examples of what I'm talking about walk up and introduce themselves and their amazing stories. These bright, articulate, purposeful, and grateful individuals tell me remarkable, life-changing stories. Oh, and by the way, they are always looking for ways to spend their intellectual capital—and many get paid for it as well.

How do you avoid the deleterious impact of retirement? Many already are looking ahead, realizing that someday they will need to apply their brakes suddenly—with their lives coming to a screeching halt. How can you avoid this undesirable condition of "retirement whiplash" in which reality suddenly catches up with decisions made? Think hard about your work, your intellectual capital, and the things you do to fuel your personal esteem and expression. Find a willing participant for this discussion, whether it's your spouse, a financial planner, or friend. Age has nothing to do with it. It's all about what a person brings to the game and how he or she longs to play. There's nothing wrong with moving from a starter to a role player in the next phase of life, just as long as you still have game.

I love to go down to the local gym and shoot baskets. When I'm there, I often see another gentleman shooting baskets as well. One day, we fell into a conversation about how much we enjoyed staying active in basketball. I mentioned that I hoped to be able to shoot baskets when I was 80. He told me he was 68 years old and that the key was very simple—"Don't ever quit," he admonished. "I've watched a lot of people use little pains as excuses, and when they try to take it up later it's too hard."

I looked at him with new eyes. He looked limber, much younger than his age, and fluid in his motion—and I knew he was right. No extended time completely out of the game for me. No time to think up excuses. I enjoy this too much.

We live in a society that still largely presents retirement as an ultimatum. Either you work or you retire. This ultimatum is foolish, counterintuitive, and counterproductive for the good of society. The recent changes in Social Security removing working limits from retirees is a flare signaling that we are no longer willing to be controlled by such ultimatums regarding work. Authors Stephen Pollan and Mark Levine said it well when they wrote that we are "no longer forced into patterns born in the industrial age." We can "forge patterns for the information age, an age in which work is more closely attuned to life. As their most powerful weapon, baby boomers can call on common sense. The marketing of retirement has produced a society that's ill at ease and full of contradictions." They conclude with a statement that reveals the utter irony of retirement as an ultimatum: "Think about it. Isn't there something wrong when we kvetch that people with limited skills collect welfare rather than work—but ask our most valuable contributors to spend their days on a golf course?"

Yes, there is something wrong with this picture. In this chapter, you will be taken on a tour revealing how our generation feels about the place of work in our life and how and why we want to continue working. We saw in the previous chapter the force that our collective voice is exerting on corporate America to desert the ultimatum—the either-or approach to working and retirement. A few years from now, retirement as a cold-turkey choice will no longer exist except in the most backward of corporate locales. Soon, mature employees will determine how long and how much they will work. This idea of phased retirement is just now gaining a foothold, and your voice will help to firmly entrench the idea as a permanent fixture in the work/retirement landscape.

First, we as individuals will reshape our ideas about work and retirement, and then we individuals will reshape our institutions. Once our ideas become grounded in the realities of the age we live in, the institutions will have no choice but to follow. It is just a matter of time before the New Retirementality that will govern the next few decades rises from below the surface to shape the policies and programs of our corporations, our government, and the retirement savings industry as well. As we have already seen in Chapter 2, this New Retirementality led to the disappearance of work limitations on Social Security recipients. In Chapter 5, you saw how this mentality is causing a restructuring of corporate retirement programs into a more flexible and self-defined model. This new model of retirement will be significantly accelerated as employees begin to assert their expectations and demands for "working retirement."

The Gallup organization and PaineWebber have conducted an ongoing series of interviews with American investors from which they produce the Index of Investor Optimism. A report entitled "Retirement Revisited" provides an in-depth look at investors' changing perspectives toward retirement. This report was based on interviews conducted with 986 investors—all of whom are nonre-tired. Fifty-seven percent of those interviewed had investable assets of $ 10,000 to $ 100,000. The other 43 percent had investable assets of more than $ 100,000. The composite picture these people show of the retirement they desire is a far cry from the cold-turkey exodus from the working world that retirees of the past have taken.

What do people want to do in retirement? The study reveals that the vast majority expect to continue with work to some degree. It doesn't seem to be work itself that people want to escape from but quite possibly the people they work for. This study reveals that the majority would like to try their hand at being their own boss. I suspect that this desire for autonomy has as much to do with the frustration of working for the inept, the control freak, and the duplicitous as much as it has to do with self-sufficiency. That aside, this study reveals four basic but distinct motivations for retirement:

Work as long as I can in the job I'm in (15 percent)—"I'm going to die with my boots on." The people in this group do not want to stop the work they are currently in. They enjoy the people they work with as well as the work they do. The only thing that will stop this group from working is waking up one day to face their inability to do the job—or not waking up at all! These individuals have found their niche and have no illusions about leaving.

Seek a new job or become an entrepreneur (60 percent)—"It's time to do my own thing." The people in this group see retirement as a chance to start their own business and follow their own dreams. First, there are those who would like to start a full-fledged business but want the security of retirement to take on such a venture. Second, there are those who would like to turn their hobby or passion into an income-producing venture.

Seek work-life balance (10 percent)—"There's more to life than making money." The people in this group recognize the need for balance in their life. Many have been speeding along on a career carousel and feel that a preoccupation with work has caused much of life to go past them in a blur. They want to continue working but at a reduced or saner pace. They want to balance their work with the considerations of family, leisure, and general peace of mind. Many in this group want to find a way to work part-time or as a consultant. The marks of this motivation are a more relaxed pace and a trend toward simplification.

Enjoy a "traditional" retirement (15 percent)—"Give me my passport, I'm outta here!" This is the group that has had enough of work and just desires to spend the rest of their life enjoying the fruit of their labors. Their plans include travel, leisure, and sitting around contemplating how much they enjoy not having to go to work anymore. Some of the individuals in this group enjoyed their work throughout their career but simply feel that they have had enough of work and desire to travel and do what they want—with no deadlines or agendas. Others in this group so hated the work that they did and the toll of stress and hardship it exacted that they now have a strong enough aversion to work to keep them from ever going back. This group might also include some who are just inherently lazy and probably spent much of their "working" career dodging work anyway.

Some interesting patterns emerge from a closer look. For example, much can be learned about the philosophical shifts of maturity from the gradual increase in the Segment 1 response: Work as long as I can. The percentage of people saying they want to continue in their current job as long as they can rises dramatically with each age group, peaking with the 50-to 64-year-old group. The most dramatic jump in this response is with women between the ages of 35 and 49 and between 50 and 64, with a leap from 12 percent to 22 percent—that is a gain of 83 percent! (See Figure 6.1.) The Merrill Lynch study confirms the Gallup opinions with some new twists—one being that 42 percent of respondents indicate a desire to "cycle between work and leisure." Only 17 percent in the study said they never wanted to work for money again. There are two conclusions we could draw from this trend in age-based thinking:

The more you mature, the more you appreciate the value of work in your life.

The increasing desire to work as you age will allay some of your fiscal fears and pressures of retirement.

Source: The Merrill Lynch New Retirement Survey, 2005

Let's examine these conclusions more closely.

You appreciate the value of work in your life more as you mature. My barber, Dave, who recently turned 50, informed me that listening to the postretirement stories in his chair convinced him to make some changes in his retirement goals. He has now decided, health providing, to keep cutting hair at least a couple of days a week, until he is in his 80s. He has also decided to not deny himself some of the pleasures of travel and leisure that he was putting off until his "retirement" years. "Why should I wait until I'm less mobile to do all the things I want to do? Why not do them while I can fully enjoy them? Plus, I enjoy this work and the contacts it provides. Why should I leave it altogether?"

My barber has recognized that the compartmentalization of work and leisure into "working" years and "retirement" years is not a healthy thing. Just as it is important to always have time for leisure, it is equally important to always have some time for work.

It is possibly a condition of youth to undervalue the ameliorating aspects of meaningful labor. It is unlikely that the young worker who sits and dreams of retiring at 35 has seriously contemplated the realities of 50 years of worklessness. There is no doubt that the closer today's workers get to retirement, the less thrilled they are with the thought of a workless life. The desirability of their career seems to grow in attraction as people age. This parallel between age and the desire to stay in one's current job might also be an indication that by the time people reach a certain age, they have settled in careers they are quite comfortable with. We might ask, for example, if you haven't found the work you like by the time you are 45 to 50 years old, are you ever going to find it? If a person hasn't found work he or she likes by the age of 50, the law of averages is against that person's making such a move after 50 for financial security reasons.

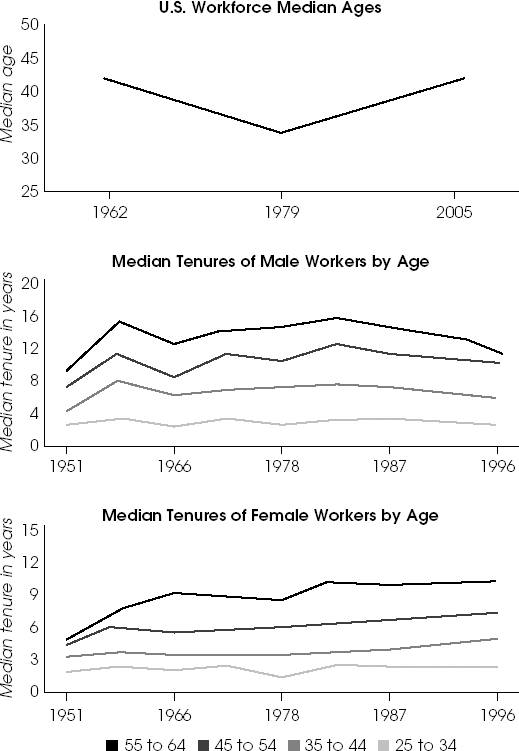

Research shows that as the workforce ages, it becomes less mobile. (See Figure 6.2.) This is as true of baby boomers as it is of any other generation. When people reach a certain age (45 and older), they look for a much more secure working situation. The average job tenure for a 45-year-old male or female worker is typically twice that of a 35-year-old worker (6 to 8 years versus 3 to 4 years). The average tenure for a 55-year-old is three times that of the 35-year-old (12 years). As the boomers age, their job tenures also rise dramatically. Another reason baby boomers will change jobs much less as they age and will begin to look for more paternalistic cultures is to feel more of a sense of safety in their mature years. Because many baby boomers have insufficient savings when they reach 45 or beyond, they will be looking more to employers for retirement security.

Source: Reprinted with permission from "Demographics & Destiny: Winning the War for Talent," copyright Watson Wyatt Worldwide, 1999

A majority of people have already made a number of career shifts by the time they reach these later working years and have an increased level of comfort in the jobs they find themselves in. When you look at the age at which people are expecting to retire based on their current age, the same pattern of mature workers desiring continued work emerges—at least for males. Thirty-two percent of males aged 50 to 64 expect to work past age 66 into their 70s, compared with only 15 percent of males aged 35 to 49. About one-third of the respondents who expected to keep working stated the reason was finances, compared with two-thirds who stated that it was a matter of choice. It could be said that it is an illusion of youth to desire a "workless" life.

I started noticing that my mother was growing progressively more uptight the closer she moved to her retirement date, which was coming in the summer. She was turning 65 and had told us about her plans to increase her gardening and her social life and maybe even to travel and see some family members she had lost touch with. But whenever we brought up the approaching date, she grew short and dismissive in her tone. So finally I asked, 'Mom, are you not excited about retiring anymore?'

'No,' she said. 'From a distance it looks like the greatest thing in the world. But as the final sands of work are falling, I realize how much I love this job. I enjoy the friendship of the people I work with and all the clients I've gotten to know through the years. They are all like an extended family to me. It almost feels like it did when all of you kids left home, except this time it's me that's leaving. We talk at work about how we'll keep in touch and all that but I know it will never be the same.'

I asked my mom if she had talked to the owner about staying on in a part-time role. She said she hadn't because she thought it would be inconvenient for him because the job required full-time attention. I told her to go ahead and have the conversation, and that she might be surprised at his response. She called me back a couple of days later full of excitement. Her boss was absolutely thrilled to have her stay on for any amount of hours she was comfortable with. He said he trusted her and would be much more comfortable knowing that she was still around to keep an eye on things and to interact with his clients.

Once we find work we really enjoy, the payoff becomes more than the paycheck. Why walk away from a meaningful payoff if you don't need to? As people age, they must be careful to not confuse the desire to cut back on working hours with the choice to retire altogether. Many reading this book may have parents who are living according to the old paradigm of the work or retirement ultimatum. They may be grudgingly accepting a situation they are not going to be happy with, like Laura's mother. In such cases the children may need to play the role of explaining the options that today's corporate climate might offer to the parent. For the person who really wants to continue working, there is a way to make it work.

The increasing desire to work as you age will allay some of your fiscal fears and pressures of retirement. It is this simple desire to keep working that will redeem not only the solvency of our Social Security system but our personal retirement scenarios as well. It is ironic to note that the work ethic of the baby boomers may be the saving grace of the Social Security system that boomers have so little confidence in. According to a Harris Interactive survey, only 50 percent of the baby boomers believe that Social Security will deliver every dollar it has promised, compared with the 79 percent in the preceding generation who have faith in Social Security. Whether baby boomers end up working past traditional retirement age because they need to or because they want to, their continuing to work will add life expectancy to Social Security coffers.

As traditional retirement continues to go out of style, the U.S. economy will benefit in many ways:

The U.S. government will realize an enormous tax windfall, assuming taxation rates continue as they are.

Much more money will be added to Social Security and Medicare, thereby postponing or eliminating the risk of insolvency.

By working through retirement years, boomers will delay the jettisoning of their financial assets. The fact that they are working will give them more time to add to their 401(k) and individual retirement account (IRA) assets.

We can safely speculate that retaining the talent and abilities of this experienced group in the workplace will end up fueling economic growth.

I remember reading all those retirement tables that said I had to have enough money to get 80 percent of my current income to be able to enjoy my retirement years. It used to make me so depressed to read those tables and calculate my shortfall. I think it's ironic how things have actually worked out. I decided to take Social Security at age 62. My employer agreed to put me on a part-time consulting contract. My mortgage is now paid, my children are grown up, and my general expenses are lower. I don't even need to take distributions from my retirement funds, and they are still growing. The financially miserable retirement hell I once envisioned has never materialized and it's more like retirement heaven. I have the money I need and I have an interesting balance of things to do to occupy my mind and time.

Many of you will continue working because you want to. Some of you will continue working because you need to; even if this is the case, you will one day realize that it was not a bad thing. Freud observed that love and work were essential to finding meaning and happiness in life. Understanding how these two forces work together can lead to lasting happiness. Lasting love requires work. Lasting work requires that we love what we do.