Money and contentment are not necessarily linked. If they were, there would be no such thing as a miserable rich man or a happy poor man.

A wealthy businessman was horrified to see a fisherman sitting beside his boat, playing with a small child.

"Why aren't you out fishing?" asked the businessman.

"Because I caught enough fish for one day," replied the fisherman.

"Why don't you catch some more?"

"What would I do with them?"

"You could earn extra money," said the businessman, "then with the extra money, you could buy a bigger boat, go into deeper waters, and catch more fish. Then you would make enough money to buy nylon nets. With the nets, you could catch even more fish and make more money. With that money you could own two boats, maybe three boats. Eventually, you could have a whole fleet of boats and be rich like me."

"Then what would I do?" asked the fisherman.

"Then," said the businessman, "you could really enjoy life."

The fisherman looked at the businessman quizzically and asked, "What do you think I am doing now?"

What do you want to be when you grow up? I began asking that question a couple of years ago, not to children but to professionals and executives between 30 and 50 years old. The answers not only surprised me but the enthusiasm with which they answered the question was the most telling of all. I met a lawyer who wanted to be a fishing guide; a marketing executive who wanted to be an ad man; a corporate communications professional who wanted to be a veterinary assistant; a saleswoman who wanted to be a radio personality; a stockbroker who wanted to be a travel writer; an electrician who wanted to be a private eye; a doctor who wanted to fix old cars; a teacher who wanted to be a musician; a musician who wanted to be a teacher; and on and on the scenarios went. It seemed that almost everyone I talked to was harboring a desire to do or try out something else to see what it was like.

I was most intrigued by how animated these discussions became. A smirk would often break out and their eyes would shine like a child exploring a new playground. People seemed genuinely fascinated with the opportunity to explore the occupational playground that often lies latent within them; the responses were noticeably visceral. While some spoke with enthusiasm, others talked with a tone of resignation, as if they had given up on the idea of ever doing something for a living that was actually fun. This tone of resignation seemed to be rooted in the idea that others had defined for them the path they were following. I do not mean in the literal sense that their parents demanded, "You're going to be a doctor or lawyer," but more in the sense of someone else assigning the values that guided their career decisions.

When I asked the individuals why they chose the path they did, many inevitably pointed to a set of values that led to the axiom, "Choose the path paved with the most money." They had contemplated their heartfelt desires in younger days, but those passionate desires to pursue a particular career were mentally dismissed because they would prove not to be materially substantive. These individuals often admitted feeling tacit disapproval and sometimes heard vocal disapproval from family and friends on those rare occasions when they did articulate their "working soul." Material compensation was the be-all and end-all of the career decision for many of these people. What many later discovered was that by not pursuing their working soul, they ended up on a path paved with fool's gold.

When the path was chosen on the basis of material compensation, many said that by the time they realized that they may have traded a calling for a job, they were so far down the one-way street of material reward that turning back or leaving that path would be too materially painful to contemplate.

Others, like the electrician who wanted to be a private eye or the teacher who wanted to be a musician, felt that at the time they chose their career, they were unsure, confused, or pressured as time ticked away. Once these individuals began a job, they often married and then had a family, followed by a mortgage and a world of obligation—and the days of dreaming were over. They had made their employment bed and now had to sleep in it. Their obligations now demanded money, and to change in midstream would cause too much stress. So the life that might have been was put out of their mind in hopes of feeling more content with the life that was. Many of these people told me that they planned on doing what they really wanted when they reached retirement age if they could afford to.

I get the distinct impression from other people that they harbor romantic notions about certain careers. If these people were to do a little due diligence into the day-to-day realities of these pursuits, they might be quickly dissuaded.

It is an odd but impressionable emotional stew that one witnesses when asking the question, "What do you want to be when you grow up?" There is wishfulness and wistfulness. There is passion and pensiveness. There is self-affirmation and self-loathing. There is almost always self-examination, which is why I so enjoy asking the question, with its inference that we have not yet grown up until we express our soul through the work we do. Every soul finds its own expression. Everyone discovers his or her own sense of meaning. It affirms to me that we all like to believe we are constantly growing and evolving.

Discovering meaning in work is a highly idiosyncratic process. Some working souls find expression by fixing things and others by fixing people. Some find expression by connecting people with people and others by connecting people with places, products, or experiences. Some souls find satisfaction by minimizing risks and others by accentuating and enabling risk. The question that we all need to ask our own working soul is: "What is it that I do with my hands and my head that gives my heart the most pleasure?" When we find the answer or answers to that question, we have at least discovered the path we should be on. Many of us possess an eclectic soul that needs to express our head and our hands in diverse ways to give our hearts satisfaction.

I remember well my parents' last words when I left home to go off to school. I'm sure I had dealt their parental hopes quite a blow when I turned down an opportunity to study at a fine liberal arts college in order to take a nontraditional educational path. I remember their last words the day I left: "We need to tell you we're really disappointed in you." At the time, those words stung and disappointed me. Today, however, I do not begrudge either of my parents for saying those words because they were simply articulating the career paradigm of the day. If your child was a good student, he or she should become a doctor or lawyer or business leader and begin climbing the ladder of wealth. If your child did not choose such a path, it was a waste of precious potential (potential defined as talent + intelligence = $$$$$).

Today, as I look back, I can feel for my parents' predicament. One month into my senior year of high school, I was going to go to a good college and study to be a writer; and a couple of months later I informed my parents that I was going to some obscure little Bible college to study spiritual matters. By the looks on their faces, clearly they thought that I had lost touch with my sanity. They thought I had lost touch with my sanity. Later, I studied psychology and counseling and, in fact, have never ceased studying matters of human behavior. I will address the matter of perpetual study later in this book. I simply was endeavoring to follow the curiosity of my own heart, and in the foolishness of youth didn't give a thought to the material compensation.

My parents and I can laugh and talk today about the irony of my contrarian choice. Because I allowed curiosity to act as my compass, I ended up in a career in which I now consult, speak, and write on matters of human behavior and relational dynamics. I feel as if I get paid too well for what I do because it all feels like experimentation and play to me. None of this would have been possible had I not pursued the holistic path of learning that began with disappointing my parents' hopes at the time. I feel I have ultimately found the greater reward by tracking my heart instead of grinding it out in a career track that would have paid well but would have taken too much from me. This is not to say that I have not taken a career detour or two from my heart and learned some lessons the hard way.

A common philosophical misconception lies just below the surface of many individuals' career choice: you must sacrifice job contentment in varying degrees to have material gain. This subtle myth reveals itself by the fact that people (1) choose to stay in careers they do not enjoy because the pay affords them the material status they desire, and (2) relegate doing the things they really enjoy to a distant retirement date. This subconscious belief is impregnated with such corollary deceptions as "I need to continue doing what I do not enjoy in order to gather enough money to be able to do what I do enjoy." In fact, money is the chief motivation for many people who are saving for retirement. Many see retirement as the time when they can do what they want. This philosophy reveals that material gain has been placed at the true north position on their life compass. If following our heart had been stressed to all of us as the true north on life's compass when we were young, would we have made different choices? It is safe to assume that many of us would have. The underlying deception that many people have unwittingly bought into is "If I do the thing I really desire, I will have to make many material sacrifices." We all need to take a closer look at this assumption before resigning ourselves to a routinized career grind.

I have discovered many people who chose to follow their passions in life and work and who actually made more money than they did in previous careers. It was erroneous thinking that led them to believe they would make less money by following their hearts—they had underestimated the economic powers of engagement!

Ellie, a career marketing manager in her mid-40s, told me how she had always wanted to help certain nonprofits but felt that such a move would relegate her life to a "not-for-profit" status as well. Then she approached a local concern with an idea for getting their message out and raising awareness; they loved it and asked if she would be willing to consult for the duration of the project. A life decision was literally forced upon her. She took on the project as a moonlight profession and then made the "big plunge": Two years later she has seen her pay rise by 50 percent and her passion for work rise exponentially.

The entrepreneurial and consulting ranks are filled with stories like these. I recently talked to a gentleman who was working for an insurance company for years but had a passion for helping parents teach their children about finance. He decided to dive headfirst into this life mission, wrote a book, began to teach seminars, and now has a successful consulting and speaking business.

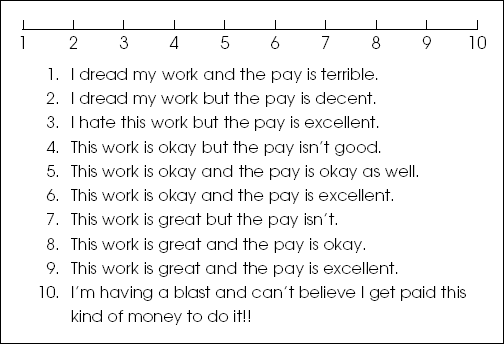

If you were to go through the thought processes of evaluating your present contentment and current level of compensation and then compare them with your desired work scenario and its associated level of potential compensation, would your contentment rise or fall? Notice that I did not ask if your material standard would rise or fall but if your contentment would rise or fall. One psychological fact of life that all individuals must awaken to if they ever want to grow up into the work of their soul is this: The philosophy of materialism is hinged on discontentment. As long as I believe that what I need most is to be happy, I will never truly be happy. It is well advertised that there is always somebody just around the corner who has more, no matter how much you have, unless you're Bill Gates. If you are serious about treating your life as something other than a dress rehearsal, then you must ask yourself which of the following categories you fall into on the work/contentment continuum. (See Figure 9.1.)

Where do you land on this continuum of contentment? First, place yourself and then ask yourself, "What do I need to do to make my life a 10 or a 9?" God forbid that you should settle for less than you are capable of. Let's take a hard look at what it means to be at different locations on the contentment continuum.

To be in this spot, you must have given up, you're apathetic, or you just haven't discovered that there are ways to enjoy your working life. The people I have met who placed themselves at this point on the contentment continuum talked about a lack of education and being stuck after they got married and had a family. This group also included those who believed that all work was a grind and you had to just tough it out until you were old enough to collect Social Security.

Some of those I interviewed who placed themselves in this spot expressed regret at not pursuing more education and also at handicapping themselves early in life with suffocating levels of debt. Others felt as if they had jumped on a workplace treadmill and didn't have the confidence or daring to jump off and enter a new arena.

For example, Phil has worked in retail management for 22 years. He bemoans the people he works for, the customers, and many of the people he works with. He says he doesn't like it, but what can he do after 22 years? The money doesn't go far (which may have something to do with his spending habits, as we noted that the difference between categories 1 and 2 on the continuum—"the pay is terrible" and "the pay is decent"—often had to do with cost-of-living choices) and it's emotionally trying to come to work every day.

Another example is Amber, a 32-year-old flight attendant with a regional airline. On a recent flight in a moment of candor, she told me that she hated everything about the job, including the travel. She had taken the job believing it would be a paid sightseeing opportunity. Instead, she found herself trapped in a carousel of homogenous hotel rooms, airplane cabins, and customer complaints. Unfortunately, she has not made any decision to do anything about her discontent other than complain and occasionally act surly to passengers. Amber is at an age where she is still trying to find out what it is she really wants to do. It's early in the game for her. She needs to realize, however, that now is the time to start moving into something that will offer more work contentment. The longer she waits, the more leverage she provides to inaction in her life.

Many people are hearing an inner alarm alerting them that they need to move from a job to a calling. For example, it was recently publicized that by the year 2010, we will have a major teacher shortage in America. How is this problem going to be solved? In large part by people leaving jobs they don't really like to do something they've always dreamed of (teaching). As a matter of fact, this trend is already under way. Five years ago in my city, the people who shifted gears and became teachers in midcareer totaled less than 1 percent. That percentage has now grown to 5 percent. The human resources director of our school system predicts that the total will reach 25 percent by 2010.

The U.S. Department of Education estimates that 2.5 million teachers will be needed over the next 10 years, which exceeds the current rate of 200,000 teachers. The "No Child Left Behind" initiative has made finding qualified individuals to fill the shortage much more difficult.

Many people reading this book are "called" to teach but are doing other things, perhaps for economic reasons, from pressure, or because of distractions, but the inner payoff will come when they do work that is in their heart.

If you find yourself in this category, it's time to get a life, get a new job, or get a frontal lobotomy so you stop feeling pain. If you're willing to work for less than desirable wages, which you've already demonstrated, then why not earn them by doing something that you at least halfway enjoy? For example, many people have avoided the teaching profession because they figured they wouldn't get rich. Now that they've gone down another path chasing "rich" and maybe finding the money was just okay, they wonder why they're doing what they do. Individuals could go from a 1 to a 4 on the contentment continuum simply by finding a job that expressed their interests.

I suspect that many people need to make a purposeful and spiritual decision about their life. I'm talking about people who are stripping themselves each day of a sense of purpose by neglecting to do the thing they feel called to do in favor of marginally more money instead of stripping their life of expenses that are not needed to the neglect of their sense of purpose and calling. To these people I want to pose two questions:

Can you find a way to live on less knowing that each day will pay you back in spades?

When it is all finished, do you think you would rather hear "Well done, good and faithful servant" or "Nice job on balancing the checkbook"?

Once you decide the right direction for your life, you'll discover the true meaning of "getting paid every day," and it will be above and beyond anything a few dollars more can buy.

If you are willing to labor for less-than-prosperous wages, then do it on a job you'll enjoy doing. Once people get this low in contentment, they have often lost the confidence to believe they can climb any higher as well as the desire for self-improvement that would spawn such confidence. At this point, your problem is not your job; it is either your lack of initiative or lack of self-regard—or both. Every step you take toward self-education, self-improvement, and self-promotion will build your sense of personal confidence, which in turns energizes your willingness to embrace opportunity and challenge. Unfortunately, the opposite also holds true—allow yourself to stay in a place that feels condescending in both task and pay, and eventually your confidence will be depleted until lethargy and numbness set in.

Individuals who allow themselves to settle into this category (of which there are many in a materialistic culture) are in a place in life where they may have exchanged their life's calling or soul work for an alluring counterfeit—pretty things. Once a person begins to collect pretty things for the purpose of self-affirmation and a sense of identity, it becomes a consuming force of perpetual motion from which few can turn away. If you live in a culture, a city, or even a neighborhood that has embraced the glitter and greed of the materialistic, bling-bling identity, you may suffer from the consternation of trying to turn your back on materialism when surrounded by it.

A friend recently told me about an acquaintance who had struck it rich in his business and is constantly buying new, more exciting cars, boats, planes, and other toys. He uses these high-ticket items a short while and then trades or sells them for something more prestigious. It's obvious to everyone that he is trying to use material commodities to fill a need they cannot fill.

The growing subculture of simplicity seekers affirms this fact in that those who seek a simpler, less hectic, less materialistic, and more balanced lifestyle often find that they must first change associations, locations, and spending habits to achieve a downshifting lifestyle. It is psychologically impossible to find material contentment when you base your life's work on the money you can make instead of the actual work you do. Those who say they hate their work but stay because the money is excellent put themselves at risk in the following ways:

They have chosen to put their dreams of achievement and maybe even their most important talents on the back shelf.

Their life and health more than likely suffer from some imbalance as a result of misplaced priorities.

Their relationships may be suffering at home and at work because of their lingering distaste for the work they do (it is emotionally exhausting to spend energy on work that drains rather than energizes you).

Because they don't care to identify with their work, they may identify with and affirm themselves through the things they buy.

In a study by Development Dimensions International (DDI), the top three reasons employees chose not to remain with an employer were:

Quality of their relationship with their manager.

Lack of work/life balance.

Not enough meaningful work.

According to Manpower, Inc., the top 12 reasons people stay with an employer are:

Being treated with respect.

Having a clear understanding of what is expected.

Having a sense of belonging.

Being treated equally.

Access to tools and resources.

Training.

Open and honest two-way feedback.

Strong teamwork.

Recognition.

Opportunities to learn, develop, and progress.

Understanding how the job contributes to the success of the business.

Security.

We all want to feel that we are making a contribution, making a difference, or doing something that feels meaningful to us. This need cannot be satisfied by the size of a paycheck. It can, however, be anesthetized by a large paycheck. Under the anesthetic we are able to temporarily ignore the need to do something meaningful and the direction our life needs to take to fulfill it. But this anesthetic eventually wears off.

One does not have to be feeding children who are starving or performing open-heart surgery to be involved in a meaningful career. The definition of meaningful is idiosyncratic. For some people it means doing something that has a direct impact on their well-being. For others, it is being part of developing and distributing a product that has an impact on the lives of others. For some, it is a matter of doing something that connects them to a cause, idea, or purpose they love, such as the rancher who loves working with cattle, the ranger who loves working in nature, the physicist who studies the heavens, or the broker who loves the markets and gaining from them.

It is a matter of deciding what interests you most and where your skills and interests can best be utilized. For some, this contemplation may lead to a career change, and for others it may simply lead to a change in career circumstances (continue doing what they are doing but in more tolerable and less stressful circumstances). I have taken many people through a series of questions that are presented in the next chapter in order to get to the heart of this issue of doing work that provides meaning in their life. After answering these questions, many have found that there is meaning in the work they do and that all they need to do is simply change their perspective and purpose in approaching their work each day. Others will look at the following questions on meaningful work and have a sort of epiphany, realizing they are wasting their precious assets, abilities, and energy where they are—and that a change is due. It should be welcome news to all of us that we don't have to be 62 to do what we want to do.

I don't know if everyone can get to 10 points on the contentment continuum ("I'm having a blast and can't believe I get paid this kind of money to do it!"), but I'm sure it's not by giving a higher regard to your checkbook than to your heart. Pay attention to both—find out where the two merge in a place of both spiritual and material prosperity. By paying attention to your heart, you can reap more contentment and move yourself toward a satisfied working life.