Fear not that your life will come to an end but that it will never have a beginning.

One day my daughter asked me to come out and play. I said, 'No, Honey, Dad's too busy.' My daughter said, 'You're always too busy' and went out to play. That night I kept turning it over in my head. Why do I work hard? Answer: to get freedom. Why do I want freedom? Answer: to spend time with those I love. When am I going to have this freedom or make getting it a priority? Answer: probably about the time my kids are gone. I realized I had put myself in a vicious cycle of motion and money and had everything turned upside down.

Iwent through a period in my own life when I allowed myself to do work I dreaded to gain money I desired. This period came to an end when I received a personal wake-up call and subsequently assessed my entire state of being by asking myself, "How much is this paycheck costing me?!"

My lesson came in a telling set of circumstances that caused me to compare what I gain materially with what I was losing physically, emotionally, and developmentally.

I had done a little consultation work for a start-up company when they asked me if I would consider taking on a consulting contract for 50 to 60 percent of my time for a fee that many would consider a generous full-time wage. On top of this, they offered me options on over 100,000 shares at 2 cents per share. The individual who offered this package had already taken two companies public, which made the offer all the more enticing. I figured I was the great American fool if I didn't take the offer, especially at a time (mid −1990s) when the word options was the mantra of a not-to-be-refused opportunity.

I reasoned that with a commitment of only 50 to 60 percent of my time, I would still have time to pursue my other ventures and opportunities, which was quite important to me as I had always been self-employed and diverse in my pursuits. What I failed to calculate into the equation was the toll that the time commitment would exact from my body, family life, and emotional well-being. The first six months were great fun and an adrenaline ride guiding the marketing efforts of a fast-growing enterprise.

The 90-minute commute to and from the office three days a week seemed to whisk by as I schemed new ways to expand the enterprise. Soon, however, some conflicts began to surface. The time commitment was much understated when I factored in my travel around the country. The owner and I operated on wavelengths that were galaxies apart. He was a consummate hands-on-everything microscopic manager, and I am an adventurous, spontaneous, and driving type. Our communication styles were on foreign wavelengths as well. I prefer face-to-face candor, and he preferred avoiding direct confrontation by delivering autocratic messages through third parties. The bottom line was that he was the boss and I wasn't! This was a most difficult spot for my personality. On top of these personality differences, he routinely put in 16 hours a day and I often sensed a tacit disapproval of my insisting I leave at 4 PM so I could be home in time to have dinner with my family.

At first, while our market share was booming, I was allowed to run with the programs I created. With such freedom, I enjoyed the experience immensely (and held out great hope for those options). Soon, however, some company culture issues became apparent. Progress toward changing direction or adopting new ideas was excruciatingly slow and depressing to my vision. By the time a decision could get made, the opportunity was lost or had been accomplished by a competitor. I grew increasingly perplexed at the lack of communication and avoidance of resolvable conflict or disagreements. And although the work itself was challenging, I was not in an area that caused my blood to race. After spending most of my career creating and selling life-improvement ideas, I was now simply selling a product—a good product, but a product nonetheless. This differentiation would become the critical catalyst in my self-assessment and eventual transition.

The wake-up call came about 22 months into my consulting job. I had to go to New York to negotiate what potentially looked to be a million-dollar deal. I was encouraged to go immediately and get a commitment. I had reservations about the need for immediacy and timing but didn't want to let the opportunity slip. My reservation about going stemmed, in part, from the fact that this trip would cause me to miss my second son's baseball game, in which he was making his first pitching start. As a matter of priority, whenever possible, I had always tried to schedule my trips to not conflict with significant dates on my children's schedules.

I told my son I regretted missing his start, but I had to go to New York to do a really big deal (with a child you might as well say you are going to the moon to gather cheese). I told him I would call right after the game to see how it went.

True to my word, I called after the game. "How did it go, buddy?" I asked. There was an eerie silence on the other end of the line.

"Dad," he said wistfully, "you should have been here. I threw a no-hitter and hit a home run and a triple!"

The longing in his voice echoed in my ear long after that call ended. It wasn't just the fact that I had missed his moment for a deal that might never transpire that bothered me the most; it was that I missed his moment while doing something I no longer enjoyed. That night I began to assess the impact of my consulting work on all aspects of my life. I began to ask myself just what this paycheck was costing me and why I was still hanging around to collect it. It was a difficult introspection that forced me to take an honest look at my priorities in every realm—from the material to the spiritual. What I discovered was that I had made some compromises that were now taking a depreciating toll on my life.

During the two years of my consulting contract, my health had disintegrated to an all-time low. I became chronically asthmatic, prone to injury, and suffered chronic fatigue and spells of depression. It seemed as though I was always struggling for breath and short of energy. I knew the asthma was the result of breathing excessive molds in the air of the company's office, which had a debilitating effect on my respiratory system. The growing stress and tension of the working environment no doubt compounded my asthma. I was tired and cranky to my wife and children after driving 90 minutes home three days a week.

The aspect of this scenario that caused me to reach the tipping point, however, was that I had become bored with the work. Although I always gave my best when talking distributors into buying our product line, I felt that I was running on automatic pilot while doing it. I was doing work that didn't bring fulfillment to my soul. The greatest thrill in my working life has always been a result of doing things that are related to convincing people to improve the quality of their lives and relationships. This mission can be fulfilled for me through a number of expressions such as writing, speaking, consulting, and media productions of the messages. Whenever I drift too far from this personal mission, I feel the anchor line grow taut in my soul—articulated emotionally by a sense of dissatisfaction and a frustrated sense of creativity. There is also a pervasive sense that I lack the necessary challenge needed to force me to keep myself sharpened in mind and daily approach. Through my introspection, I realized that I was driving down the wrong way on the road to fulfilling my personal potential. The paycheck was costing me too much.

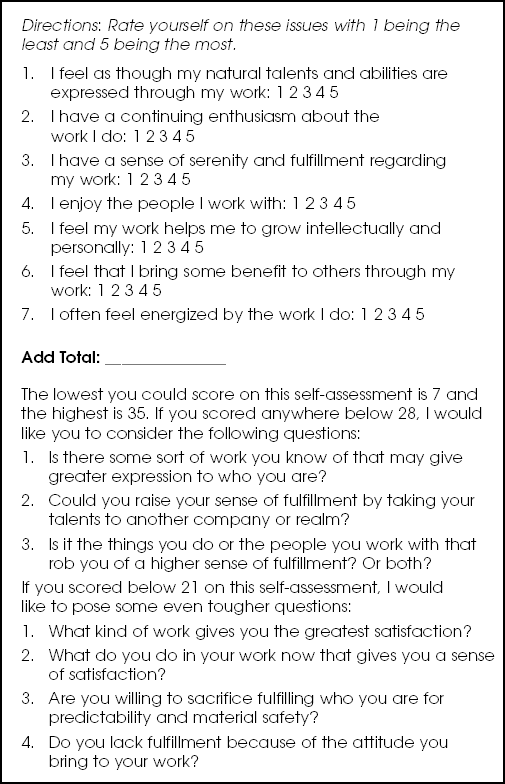

Figure 11.1 is an introspection, a mental journey, I like to guide those on who find themselves anywhere below a 7 on the contentment continuum. If you have an intuitive sense that you are not fully utilizing your talents and abilities, or if your work does not draw on the things you do best, you are ripe for such an introspective examination. Grappling with these questions can be a humbling but liberating process.

As a result of hundreds of such discussions with people, I cannot help but believe that responses to these questions are signals from our souls guiding us to choose, change, or alter our mind-set and the application of our abilities. Answering these questions positively is a signal that we are following the work path that our soul requires for contentment. When we answer negatively, however, it is a signal that we are on an unrewarding work path or are bringing the wrong attitude to the right place. As Stephen Covey so succinctly asked in The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People (Fireside Books, Simon & Schuster, 1989), "What's the point of climbing the ladder of success if it is leaning against the wrong wall?" I might add a question that pertains to those who bring the wrong attitude to the right kind of work: "What's the point of climbing the ladder of success if you're only going to look down?"

Career coaches like Laura Berman Fortgang confirm that a majority of the clients they see end up staying right where they are after a consultation on work-fulfillment issues. Fortgang, author of Take Yourself to the Top (Warner Books, 1998, says, "Nine out of ten people who call me, desperately looking to change their careers, wind up staying in their jobs." How do you know if you're one of the one in ten who needs to move on? Fortgang suggests looking for these three telltale signs:

Your work doesn't mesh with your life. If the work severely clashes with the rest of your life, you need to move on.

You've outgrown your job; your job needs to jibe with who you are today.

You've fixed the things that drive you nuts. And you're still miserable. Your job dissatisfaction has become chronic. You won't get better without a change.

Many people—nine out of ten—who were suffering much discontentment and job-related stress discover that they begin to see their work through a new set of eyes when they shift from a mind-set of expecting happiness to looking for growth. It is easy to grow disturbed and agitated in our work when we are constantly looking around at what others make and what others get to do instead of trying to capitalize on the growth opportunities that our job offers us. When we are driven by a sense of psychological entitlement that demands things go our way, it doesn't take long for ingratitude, envy, and stress to dominate our mental realm. On the contrary, when we shift our focus on growing and exceeding the various demands of our work, we begin to discover a new sense of anticipation and fulfillment in our work.

It is quite easy, however, to let the annoyances of frustrating personalities and circumstances at work rob us of the joy and growth we could harvest from our work. It doesn't take long for stress to get the best of us and for our mind to start wandering by wondering if we would be happier doing something else somewhere else. When career coaches guide their clients through a thorough examination of that question, they often find the clients realizing that their work does, in fact, have many opportunities for growth and satisfaction—and maybe isn't such a bad deal after all.

The last of our human freedoms is to choose one attitude in any given circumstance.

—Viktor Frankl

A periodical attitude evaluation usually helps to pull us back to the reality that there is no perfect world and that familiar and predictable trouble is always preferable to unfamiliar and unpredictable trouble. A simple attitudinal exercise you can do is to take inventory of the opportunities for personal development that your current job affords you and determine what skills you are developing and can develop that will make your r é sum é look that much better tomorrow.

Does my work provide the opportunity for desired intellectual growth?

Am I forming valuable relationships and contacts in this work?

Can the tribulations of my current work contribute to needed skills in future work?

In my response to current conditions, am I rising above it or living under the circumstances?

Am I seeking the company of the groaners or the growers?

If opportunities for growth still exist, it might be best to bloom where you're planted. If such opportunities do not exist and you're beginning to feel like you're going in circles, it might be time to uproot.

I learned in my personal wrestling match with the issues described above that I would never feel a higher sense of work fulfillment until I cut my ties to the work that required less than my highest level of interest and ability. I decided that I needed to dedicate myself to the philosophy I had already established, which was doing work that challenges people to think about their relationships and their quality of life. This book is an expression of that philosophy. I sense that as long as I follow this direction, I have the inward contentment of being on the right path. There are always risks associated with such decisions, but, in my opinion, these risks are far less dangerous than the risks of compromising deeply seated visions and desires for your own life. The risk of ignoring those desires is the depletion of your physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual strength. Once these precious resources are depleted, you find yourself getting sick in both a physical and emotional sense.

Dr. Paul Stepanovich, who taught community health at Old Dominion University, advised people to give their employer a fitness test. Stepanovich says there are certain warning signs he wishes he had been aware of when he was climbing the corporate ladder in the 1980s. He states, "It struck me that although I had read about stress in my MBA program, I couldn't believe that I could visually see the effect on people's health" (as quoted in Carla Bass, "Give Your Employer a Fitness Test").

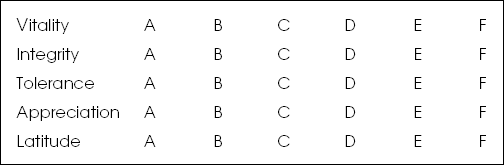

When Stepanovich went back to school to earn a degree in epidemiology, he decided to dedicate his research to uncovering the prevalence of unhealthy work environments. Stepanovich says, "I don't think we have any idea how sick some organizations are." He recommends giving your prospective employer a fitness test before jumping aboard. If you don't, your new job may end up costing you more than you're paid. Where you work can affect not only your quality of life but how long you live as well. Stepanovich has developed a list of vital signs to measure a company's emotional healthiness. The health of any organization seems to hinge on five characteristics: vitality, integrity, tolerance, appreciation, and latitude/empowerment.

- Vitality.

Employees are interested in what they are doing and they care about it as well.

How to test for it: If possible, see if you can spend time shadowing current employees for a day or even a few hours. Check to see how involved they are in their work. Are they intellectually and emotionally involved with their tasks or are they just going through the motions in a detached sort of way?

- Integrity.

Current employees have a high level of trust in their employer.

How to test for it: Talk to current employees to see if the company "walks the walk" as well as "talks the talk." Does it promise training and growth opportunities to prospective employees that it fails to deliver? Ask current employees what they were promised and see how much integrity the company demonstrated to these individuals.

- Tolerance.

The company demonstrates equal opportunity for advancement for all races and both genders as well as the acceptance of differing viewpoints.

How to test for it: A quick perusal into the management offices will give you an idea of the type of individuals that get promoted. If possible, sit in on a meeting; it will give you a good idea of the tolerance level toward different viewpoints and conflicting opinions.

- Appreciation.

The company demonstrates a high level of appreciation and recognition for achievements and rewards a job well done.

How to test for it: Check to see if current employees feel that their job is highly important to the success of the company. Companies that promote an ethic of appreciation and recognition foster a higher self-image in every department of the company. Every employee has the feeling that his or her performance is crucial to the company's success.

- Latitude.

The company empowers employees to take risks and exercise a reasonable degree of autonomy.

How to test for it: Talk to both managers and employees to see if they have the space they need to do their jobs. Working for people who drive you crazy with control tactics and job interference causes the worst sort of workplace stress. Punishing people for results out of their control and micromanaging every detail will cause the sort of tension that can make your working life miserable.

This acid test for a prospective employer is just as relevant when measuring your current employer. How does your current employer stack up from an A to an F on the vital signs report card? (See Figure 11.2)

If you are a manager, you may be interested to know that you can bring a great degree of influence to the vital signs of your particular department or team. When it comes to rating their bosses, most people say that their leader's attitude is what matters most. A national survey of 1,000 people chosen randomly by Personal Decisions International, a global management and human resources consulting firm, found 37 percent of the people surveyed identified communication skills or interpersonal skills as the most important quality in a good boss. The ability to understand employees' needs and help in developing skills came in second (19 percent). In an article entitled "Trouble Finding the Perfect Gift for Your Boss—How About a Little Respect?," an Ajilon Finance survey reports that most people agree they want a boss they can respect. When people were asked to select one trait that is most important for a manager, more than one - fourth of American workers selected "leading by example." Of all qualities from which they could choose, employees ranked the most important as follows:

Leading by example (26 percent)

Strong ethics or morals (19 percent)

Knowledge of the business (17 percent)

Fairness (14 percent)

Overall intelligence and competence (13 percent)

Recognition of employees (10 percent)

This need for the opportunity to achieve growth was confirmed by the Aon Consulting survey of 1,800 employees that found the opportunity to grow as the top reason for employee loyalty.

When people assess the emotional well-being of the company they work for, many find that their workplace is "calling in sick."

Many companies still get away with abusing employees—simply because they can. A company is usually doing something well, whether it is in a specialized market or a key technology or has some other advantage that makes it competitive. Stepanovich witnessed many corporations where "[p]eople were horribly unhappy but were getting paid so much money that they would get the mortgage and the family commitments and they would just kind of get stuck." This common phenomenon of prosperous discontent is the result of allowing ourselves to compromise what we want to do with our life for what we can accumulate with our labor. In such a case, our paycheck has proceeded to rob us blind.

One of the first signs that this process of compromise may already be under way is when you derive material satisfaction only from your work. Once this happens, people begin to measure themselves by their possessions rather than their contributions. They have exchanged their work fulfillment for a counterfeit, material significance. The ultimate scenario we can achieve is to do fulfilling work and be rewarded materially in such a way that causes us to feel truly grateful. This is not to say that gratitude is not possible at various levels of compensation. This sense of gratitude has much to do with a person's level of material wants and preferences. Once a person opts for the counterfeit and makes material gain the sole purpose and not the result of meaningful labor, it's only a short time before workaholism and neglect of relationships begin to surface.

My friend runs a nanny service in the Midwest and serves clients in big cities. She told me that many of the people who employ her service work from 7:00 AM to 9:00 PM, even on weekends, and rarely see or interact with their children. Yet these people specifically call my friend's service because they want an Iowa girl with 'good midwestern values.' How ironic.

—Connie, 35

Many of those who have children struggle with maintaining the balance between practical material needs and family needs. Nowhere is the dilemma between material progress and relational priorities greater than with working mothers. Studies show that many mothers carry a significant sense of regret and guilt to work each day over the absence of time with their young children. In one study, 38 percent of working moms said they would take a new job with less pay if it meant they could spend more quality time with their families. One-fourth of working moms would accept a pay cut of over 5 percent, and 15 percent of working moms would accept a pay cut of over 10 percent. I have interviewed many who began to question the wisdom of working as many hours as they do when almost half of what they earn goes toward paying someone else to watch their children.

This issue of spending more time with the family is not restricted exclusively to the female gender. A recent study by the Radcliffe Public Policy Center revealed that younger men were the most willing to give up some pay to have more time with their families. Over 70 percent of men 21 to 39 said they would give up pay for family time. Employers are now seeing more fathers who telecommute, attend parenting classes, and take time off for family.

Paula Rayman of the Radcliffe Public Policy Center calls it "an evolutionary shift in gender expectations," adding that "men are saying they want to be in their children's life the way their fathers and grandfathers couldn't be."

Another factor involved here is the number of men who are now primary caregivers. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2004), there are now more than 3.3 million children living with their fathers, which is three times the number there were in 1980.

When Charles Schwab held classes on balancing work and family, more men than women attended. Because of the tight labor market, employees have been feeling bolder and more secure asking for accommodations for family life. It is also apparent that women's expectations of their partners have changed. It is no longer assumed that the male is the principal wage earner.

Peter Baylies, who writes a newsletter for at-home dads and who left a programming job in 1993 to care for his children, sums it up this way: "A lot of dads don't want the stress anymore of staying at the office until 10 o'clock. ... Now, a good family equals success."

A friend of mine, a working mother, told me the following story:

In the last year I have grown weary of watching a day care center raise my children. My youngest girl has one year left before she's off to full-time school. I sat down one night and figured out that I was working one-half of my hours just to pay for the day care. It made no sense whatsoever, but I had been doing it while my two children were growing up. I assumed that I had no other option with my job, which I had held for 13 years. I had approached my supervisor before about possibly working part-time or designing hours that fit better into what I wanted in my life, but she said it wouldn't be possible. I finally made up my mind that I would leave and go somewhere else where I could get the flexibility I needed. When I went in to inform my supervisor of my decision, she had a whole different posture in the situation. Suddenly, she could find a way to accommodate me with the hours I wanted. I'm now staying put with hours that fit my life, and I am at home with my youngest child in the morning. I have never been happier. I guess I had no idea that I could make my life this much happier just by asking.

My friend's story illustrates just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the work scenarios that cause people to feel as though they are missing something meaningful in their life. It may be the career they've chosen that causes these feelings, or they may be in the right career but pursuing it in the wrong place. In the above example, it was a case of being in the right career in the right place but working the wrong hours for the stage of life she was in. It is important to pay attention to this feeling of purpose and meaning and whether it is being fulfilled in your simply make money. People are designed to make a difference, and material gain is simply a chief by-product.

We are often quick to calculate the material benefits of the work we do but are reticent to calculate the emotional, physical, and relational liabilities we may have to trade to receive those benefits. Every inch we gain in this world costs us something. The question to be answered is: "Is this paycheck taking away more than it is giving?" When I realized that the work I was doing was chipping away at the energy, creativity, and optimism that had made me what

I was, I knew that sort of paycheck deduction was too high a price to pay.

What does all this have to do with the New Retirementality? Everything! Many people's retirement fantasies are fueled by the idea of escaping employment that has had an eroding effect on their person over the years. Some people feel at 50 that they are just a shadow of what they were at 38. This is a sad statement about life and employment. Retirement from a career that has robbed us of personal qualities, irreplaceable relationships, and prime years of physical health will not replace what is lost. Retirement, for some, has given them time to repair their health, relationships, and desire to follow their soul's work.

Denny Stone was once ensconced in a high-pressure management job with a computer company. His life fell apart when his wife of two and one - half years died of cancer. Stone felt his foundation crumbling beneath him. He sold his house and left his company in a quest to figure out what was important.

His sabbatical lasted two years, and he eventually returned to the same company, albeit in a different job. Stone's time away convinced him of three principles regarding his work:

Reconnect with your passion. Why work on things that don't matter to you?

Take on new experiences. You'll surprise yourself at the undiscovered aptitudes you possess.

Listen to people you trust. Ask the people around you what you're really good at to get better direction for your efforts.

Stone's time-out paid a lasting dividend. According to Stone, "I don't check my life at the door when I go to work anymore and then pick it up on the way out. Life and work are no longer separate."

If you've been mentally or emotionally detached from your work, it's time to reengage. First, rededicate yourself to your job. Determine to give it an appropriate amount of your undivided attention. Second, figure out why you have been detached. Do you need new challenges? Are you in conflict with your boss or coworkers? Are you in a dead-end job? Identify the source of the problem, and create a plan to resolve it.

—John C. Maxwell, author

Don't just look in the mirror; look around you. Look at the price some people are paying for a paycheck. There is something to be learned by observing what people allow themselves to trade for their paycheck. I have made notes of the people I have met over the years who have made inequitable trades. I have seen firsthand what people have chosen to trade for their paychecks:

A redeemable marriage or relationship

Meaningful relationships with children Personal dignity

Dreams and ideas

Physical well-being

Optimism for life

Balance and relaxation

No paycheck on the planet is worth any of the aforementioned trades. When we find work we love and carry on that work in balance with the rest of our life, we eradicate the need for retirement. Life was not designed for us to work myopically for 40 years to the neglect of all else and then try to catch up for lost time in retirement. With some introspection, proper guidance, and persistence, we can find work we will always enjoy. If we find that this work comes with a good paycheck, we will enjoy it even more.