Chapter 10

The Revolution in Alternative Investments

We will discuss the dynamism and innovation that the “PayPal Mafia” is bringing to the table in future chapters. First, however, we need to discuss the other large institutions that have been around for some time and that are now spreading their wings and challenging banks in many new areas. They are breathing down the necks of banks as they enter businesses where banks must exit, either due to regulatory pressure or because they simply do not have the balance sheet liquidity to compete. These entities have the flexibility to change and morph. They are also capable of quickly adapting financial technology in their models. We shall see that one firm, Goldman Sachs, is very likely further ahead than any other major bank globally in terms of adapting financial technology for their own use and that of their customers.

Indeed, Antony Jenkins said in the Financial Times on December 18, 2014, that “the universal banking model is dead.”1 In this heretical statement, he indicated that the use of customer deposits from commercial banks is no longer an appropriate way to fund investment banks. Regulators are now stopping this practice and are, in effect, breaking up the commercial and investment bank units into two separate groups. Mr. Jenkins also implied that the speed of technological innovation is the key to the future. Banks with dozens of locations in several continents simply cannot invest in technology in so many places quickly at the same time without making mistakes. Large banks with multiple divisions and with multiple footprints globally are disadvantaged on this score. Furthermore, there is a shortage of capital, which forces banks like Barclays to raise even more capital or shut down divisions. Lastly, many investment banks have lost the confidence of many regulators, and there is ill will in the air, which makes cooperation between local branches and regulators/central banks problematic. (As a result, we should anticipate that banks like HSBC will either break up or list entities inside countries on stock exchanges as separate legal entities. Will HSBC or Standard Chartered follow the Santander model? I think so.)

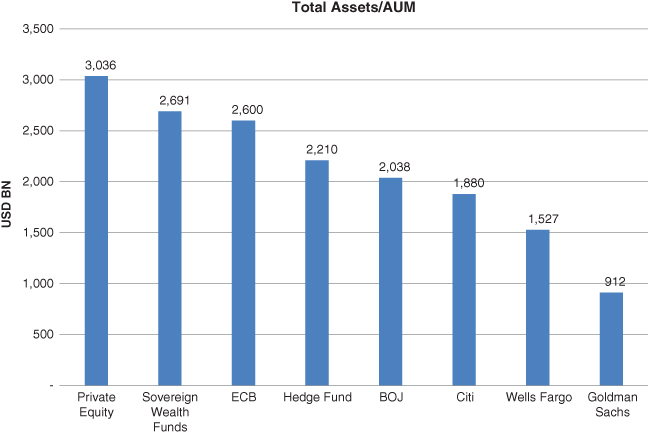

Does size matter when it comes to creating alternatives to banks? This is an important consideration, as size creates momentum and momentum creates ecosystems. Ecosystems in turn create political support. This political support creates acceptance and wide-scale use, which produces regulatory acceptance. We can see from above that private equity is now the largest form of funding globally and dwarfs the largest banks in the United States, for instance. Private equity is larger than either the balance sheet of the European Central Bank (ECB) or Japan (figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1 Can Private Equity and Hedge Funds (Buy Side) Replace the Sell Side?

Source: Schulte Research Estimates, company websites.

Sovereign wealth funds are organs of sovereign governments. These entities are charged with investing the foreign exchange reserves of governments. These entities have wide mandates and range from public equities, private equity projects, bonds, and commodities to foreign exchange. They often engage in projects that are mandates from politicians within the central government. As a result, conflicts of interest often arise as political decisions are made that may not reflect national interest. Furthermore, these same politicians may wish to place people inside the funds who are amenable to certain types of investments. As a result, overall performance suffers. Norges has the best reputation among the funds for transparency and performance. On the other hand, China Investment Corporation (CIC) has suffered due to interference and politicization of the fund.

Hedge funds have been growing from strength to strength and now total about US$2.2 trillion. We will see how these funds are funding the boom in Silicon Valley at a time when the banks are mostly excluded from this activity. Hedge funds are spread globally among the United States, London, Hong Kong, and Singapore—and let's not forget that the hedge fund industry in China is only beginning. It will have explosive growth over the coming years and could easily exceed US$1 trillion within five years or so.

Private Equity: Much Dynamic Activity To Replace Businesses That Banks Exited

For private equity firms, their sheer size is a great asset. The top five alone have unleveraged assets of about US$150 billion. Their willingness to engage in new ways to bring life to dying businesses that the banks were forced to abandon is impressive. For instance, the fourth-largest firm, Apollo, is active in trying to resuscitate the mortgage-backed securities business. The reactivation of this business will bring greater liquidity to the residential housing market.

If we look at many of the major buyouts, mergers, or privatizations in the past few years, private equity firms are doing much of the heavy lifting that investment banks were doing in the past. The privatization of Neiman Marcus, for instance, was done by TPG without any help from any major investment banks. The same goes for the buyout of U.S. Foodservice by Sysco. The acquisition of Beats Electronics by Apple was done without any investment bank. Many other financial transactions in the multibillion range are now being done without global investment banks. Furthermore, many technology firms are themselves bypassing investment banks altogether and hiring in-house lawyers and bankers. In this way, there is no need to hire an investment bank at all.

This sends a chill down the spine of investment banks, since even major acquisitions in Silicon Valley are now being done without any participation from banks. For example, Facebook and Cisco have internal investment banking teams and no longer rely on Wall Street banks. According to Dealogic, 70 percent of deals in the area of acquisition did not involve a Wall Street bank. This is up from 25 percent 10 years ago. Apple's purchase of Beats Electronics did not involve banks but in-house private equity specialists. The same goes for the purchase of Oculus by Facebook. California investors are distancing themselves from traditional investment banks rapidly, and this trend seems unstoppable for now.

Furthermore, these financial institutions are offering returns that are multiples higher than the returns offered to shareholders of banks. For instance, the Carlyle Group offered an internal rate of return of 30 percent to its investors. The average for the top five investment banks was a paltry 2 percent return on capital. The return on equity for KKR was 27 percent in 2013. The average return on equity for the global universal investment banks was about 9 percent. The more time that passes, the greater will be the capital bases for private equity, and the more traditional investment banks will struggle to fund what is currently on their balance sheets. Private equity funds are very definitely morphing into entities that can offer a broad array of services, and corporations are increasingly relying on in-house advisors, bankers, and lawyers to complete mergers and acquisitions. What's left for the banks?

Another company creating innovation and dynamism in the world of finance is Blackstone. It has US$66 billion in assets and has a portfolio of 72 companies. It has 20 percent of its business in Europe and 10 percent of its business in Asia; the rest is in North America. It has a diverse portfolio that ranges from SeaWorld to Crocs to hydropower. In this space we will also find TPG and Grosvenor. (Grosvenor is very closely allied with powerful political figures in Chicago.) These organizations are very definitely morphing and challenging global investment banks in many areas of traditional funding. In turn, these private equity funds offer capital to high-yield bond funds, mortgage-related entities, and diversified financial companies, which are also threatening incumbent banks. These entities have created an ecosystem of private money that has become an alternative funding source. We will see in a moment that it is these types of companies that are funding the revolution in financial technology—not the banks.

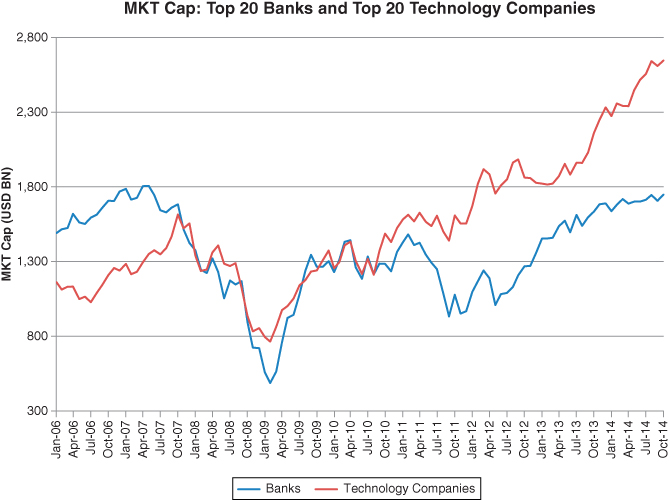

Hedge Funds Are Backing Technology and Have Abandoned Banks

Hedge funds are also morphing and offering new forms of capital to businesses. They are diversifying away from public markets and taking on business lines similar to private equity firms, mortgage-backed entities, and supporters of financial technology in California. To give an idea of how much the hedge funds are moving away from traditional financials and toward technology, I looked at the top 20 tech companies and the top 20 banks in 2007 and tracked their performance. In 2007, the top 20 banks globally had a market capitalization of about US$1.8 trillion, while the top 20 companies had a market capitalization of US$1.1 trillion. Cut to the end of 2014, and the market capitalization of the banks is US$1.7 trillion. This represents a drop of 6 percent. At the same time, the market cap of the tech firms moved to US$2.5 trillion, an increase of 127 percent. In other words, the banks are still below their values of 2007, while the capitalization of the tech firms has more than doubled. Figure 10.2 shows the evolution of technology (and a good part of this is financial technology) relative to the banks.

Figure 10.2 Global Investors Are Shunning Banks for Fascinating New Technology

When I explored the top holdings of the largest hedge funds globally, I discovered that most of the top holdings were in fact technology. Furthermore, the top 20 hedge funds globally held almost no banks at all. They owned Amazon, eBay, and American Express. That's about it. But there were no banks to be seen in virtually any of the major holdings of any of these hedge funds. Shouldn't that tell us something? These are some of the smartest people in the world of finance.

The holdings of these funds include many stocks in the life sciences. Hedge fund managers seem convinced that the greatest share of rerating and revenue growth will not come from banks, but from (a) an evolution in the human genome; (b) developments in the marriage of biology, chemistry, and transistors to create solutions to diseases by way of human implants; (c) new developments in pill-form drugs for cancer, disease, and mental disorders; (d) developments in military hardware that reduce human casualties; (e) technology that can allow the consumer to bypass the mall, the bank, and the credit card company and shop cheaply from home; and (f) entertainment and educational systems in the home that are exciting, fun to use, and instructive. Banks are simply not on the horizon.

As an example, the top two individual stock holdings of Bridgewater as of late 2014 were Microsoft and Verizon. The top holdings of AQR, the second-largest hedge fund globally, are Google, J&J, Microsoft, and Apple. And the list goes on. There are just no banks. One company that is heavily owned by Och Ziff is China Cinda, an asset management company that is designed to clean up the bad debt of the banks. A few of these large hedge funds own insurance company Metlife and American Express. And that is the extent of the ownership of financials. Is this the sign that it is time to switch? I sincerely doubt it.

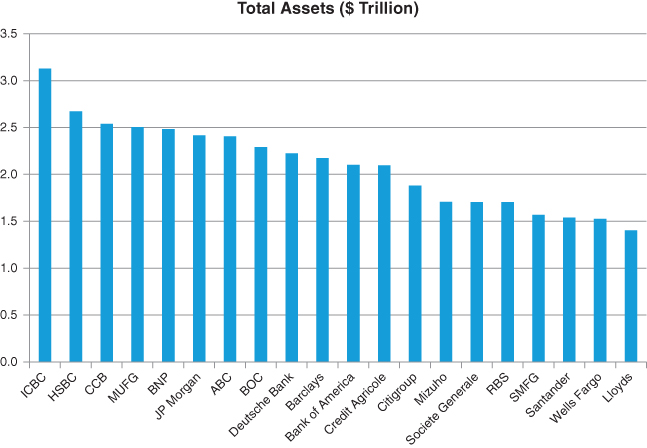

As we shall see, there is a real need to clean out the financial system and engage in a fairly radical restructuring of the balance sheet. It is unwise to be an equity shareholder of an industry that is undergoing heavy consolidation. I believe that this is exactly what will happen. Banks like Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Société Générale, BNP, and Barclays are simply too big to survive. Consider: Dinosaurs very likely got so big because the oxygen levels in the atmosphere allowed them to grow larger. At some point, oxygen levels fell by a few percentage points—meteors, volcanos, whatever—and could not support the size. I submit that is exactly what is happening today. The ecosystem can no longer support the absolute size of these entities, and they must break up into smaller and more flexible and dynamic organizations. Furthermore, firms like BlackRock are building horizontal organizational structures that create separate, smaller units with an entrepreneurial spirit. So far, they have succeeded in creating world-class centers of excellence with groups of about 60–100 people. BlackRock is one of the “large” firms that is creating the new enterprise by creating many smaller centers of excellence.

Figure 10.3 shows how large these beasts have become. John McFarlane will enter Barclays in 2015 and will likely break up the banks. Similarly, the FSA is being more aggressive in forcing banks to separate their commercial lending groups from their investment banks. If so, this will cost billions and will force a few banks to close down their investment banks, for the simple reason that the investment bank will no longer have a funding source. Equity shareholders of these banks should be aware: This is not a good time to own these banks. They need to avoid simply collapsing under their own weight as they find new businesses, close branches, reduce headcount, deal with prosecutors, and write off bad assets. See Figure 10.3 for the largest banks in the world. HSBC, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, and BNP will be under large pressure to reduce assets going forward, and the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) is probably in this category as well.

Figure 10.3 HSBC, J.P. Morgan, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, BNP, and Citi Need to Shrink

There is one important exception in the investment banking sphere. Goldman Sachs is further ahead than any other bank globally in their ability to maneuver, morph, and adapt to new circumstances. Goldman Sachs is heavily involved in buying private equity stakes in financial technology firms and associated technologies in California. They can now boast a portfolio of financial technology in excess of US$10 billion. They dipped their toes in the financial technology waters years ago and now are reaping the rewards as they integrate these technologies into their client platforms. They have invested in Big Data firm Applied Predictive Technologies. They bought Perzo and used it to develop Babel, an encrypted messaging service that now competes with Bloomberg. They bought a US$450 million stake in Facebook in 2011. They have stakes in Alibaba, PSI, Square, Acquia, ZoomSystems, and several others. This offers them an ease of comfort to analyze future financial technology, and puts them in the lead among global investment banks.

In the meantime, other global investment banks like HSBC, Standard Chartered, Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse, and a few others have been unfocused, timid, or careless about the future of financial technology. Goldman Sachs has momentum on this score and is creating its own financial technological ecosystem. Other banks that do not do this quickly will very definitely lose out. Many investors with whom I have spoken wonder if these global investment banks can ever catch up after these years of bumbling about with regulators, lawyers, and prosecutors. My conclusion from talking to a number of my clients globally is that these banks are simply too far behind to catch up and will need to break up and hopefully recreate themselves in some productive way without collapsing under their own weight.

Sovereign Wealth Funds

Sovereign wealth funds are strange creatures. They are part political, part selfish national interest, part capitalist. There is often nepotism, as senior people are placed in positions of power that are related to the leaders of countries or are placed there for political purposes. So, the management procedures and investment processes are often chaotic or nonexistent.

Sovereign wealth funds are using their own money (without any leverage from banks and without any external advice from banks) and their own in-house lawyers to conduct their own investments. The largest globally is Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, at US$775 billion. CIC is up there at US$575 billion, and Singapore's sovereign wealth fund is also a behemoth at US$320 billion. CIC is an example of when sovereign wealth funds are used to clean up messes or to engage in investments for national purposes. When Bank of America and Goldman Sachs were in trouble many years ago, they were forced to sell assets. Bank of America sold its multibillion-dollar stake in China Construction Bank, and Goldman Sachs sold its multibillion-dollar stake in Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC). CIC (and its sister company, Huijin) was called to the rescue to buy part of these shares in the market (or through block trades) in order to prevent the stocks from precipitously falling.

One of the vitally important dynamics to remember is that many of the decisions of the sovereign wealth funds are political in nature. They will always deny it, but the evidence often points to clear political (or crafty geopolitical) motives. Some of these are secret arrangements between governments that are made for various reasons. A fund like Huijin—the internal local currency sovereign wealth fund of China—engages in pricekeeping operations and is often a forced buyer of stocks to support the prices. As a result, performance of many of these funds suffers. Table 10.1 shows the performance of many of these funds.

Table 10.1 Sovereign Wealth Funds by Size and Returns

| Annualized Return | |||||||||

| SWF | Year Founded | Total Assets ($BN) | 1 Year | 3 Year | 5 Year | 10 Year | 20 Year | 30 Year | Since Inception |

| ADIA | 1976 | 773 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7.6% | 8.2% | NA |

| CIC | 2007 | 575 | 10.6% | 5.7% | 5.3% | NA | NA | NA | 5.0% |

| GIC | 1981 | 320 | NA | NA | 2.6% | 8.8% | 6.5% | NA | NA |

| TEMASEK | 1974 | 173 | 9.0% | 5.0% | 3.0% | 13.0% | 14.0% | 15.0% | 16.0% |

| KIC | 2005 | 57 | 11.8% | 5.4% | 3.7% | NA | NA | NA | 4.3% |

There was another very important development involving sovereign wealth funds during the global financial crisis that has caused further reputational damage to global investment banks in their dealings with sovereign wealth funds. At this time of extreme distress in the financial system, banks were desperate to raise new capital, and public markets could not digest the large amounts of money that were needed. So, the banks went to sovereign wealth funds to find new capital. Morgan Stanley went to CIC to raise money and was successful. When Morgan Stanley faced another problem and needed more capital, the original investment from CIC was underwater and CIC thought it would be given first priority for a discounted second offering. After all, CIC had saved Morgan Stanley's bacon. Instead, many insiders say that Morgan Stanley went behind the back of CIC and gave the deal to Mitsubishi UFJ Finanical Group (MUFG) in Japan. It was a better deal for Morgan Stanley, and MUFG finally made money on the deal years later. But this was seen as a rebuff for CIC and a public embarrassment. China has a long memory.

Another deal that went south was an investment by the private and secretive China Development Bank (CBD) with Barclays. This deal went sour quickly and caused a great deal of embarrassment for China and CDB, which is considered a vital jewel in the crown of China's financial system. Similarly, investments in Citi, Merrill Lynch, and UBS all went badly south for the two sovereign wealth funds in Singapore. And Temasek's investment in Standard Chartered is seriously underwater. These sovereign wealth fund people talk to each other, and there is a lot of bad blood from the deals that were made in the midst of a crisis and transacted quickly. However, there are too many people in too many of these institutions who feel hoodwinked at worst or misled at best. It will take many years for any of these wealth funds to help out global investment banks after they were systematically burned by so many of them in such a short period of time. We are not talking small amounts: The combined losses by these two sovereign wealth funds through bad investments in these banks can be measured in the tens of billions.

The primary trend we see today among most of these funds is that more of their assets are being externally managed by hedge funds, private equity funds, mutual funds, ETFs, industry-specific funds, or large-scale projects that are government-to-government investments in infrastructure, power, or transport. In this way, sovereign wealth funds can reach out internationally and fund projects with special concessions and rates of return with long-term capital in ways that banks no longer can. Also, these funds are massive passive investors in some of the largest companies in the world.

Another interesting creature is the Abu Dhabi Investment Council (ADIC). It has about US$90 billion in assets and acts as a strictly private equity entity in its investment mandate. This organization does a lot of interesting investments in aircraft leasing, infrastructure funding, alternative energy, and technology. As with other sovereign wealth funds, ADIC has certain internal obligations and must perform national service to the government of Abu Dhabi. So, some of its strategic investments include Abu Dhabi Aviation, Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank, and Abu Dhabi National Insurance. It does no business in public equity markets or in public bond markets. In this way, it has a mysterious presence, as all of its activity is off the radar screen of public pricing.

Lastly, the new competitors to the business of banking are central banks. The Federal Reserve has been doing a tremendous amount of heavy lifting as it tries to avoid a deflationary depression. So, it is buying assets from private banks and quasifinancial organizations in order to prevent downward pressure on asset prices. We covered this in earlier chapters. Suffice it to say that the private sector purchases of risk assets (as well as government bonds) is bringing about a dynamic where central banks now have assets that are a multiple of private banks. Let's not forget that other than currency in circulation, the Federal Reserve owned virtually no other assets prior to 2008. Cut to 2014 and we see that the assets of the Federal Reserve are now almost equal to the combined assets of Citi, Wells Fargo, and Goldman Sachs combined. The balance sheet of the Bank of Japan is now approaching 50 percent of GDP of the country. And it announced in late 2014 its intention to purchase billions of dollars in equities as well. This is an attempt to reflate the economy and remove the danger of deflation on financials assets.

In conclusion, we will see in the next chapter that technology firms emanating from Silicon Valley, New York, London, Scandinavia, and Japan are, like termites, eating away at the foundation of many of the businesses of the banks. This is a phenomenon that has been occurring for the past four years from a standing start. Other firms we described above have been in place for a decade or two and have veteran bankers who split off and started their own firms. These industries, like private equity, hedge funds, mutual funds like BlackRock, boutique banks, and sovereign wealth funds, not only are shunning global investment banks as investments but also are carving out new businesses. In some cases, they are creating entire new lines of business that are a direct threat to the banks. Lastly, firms themselves are taking matters into their own hands and are shunning the tainted reputations of banks, as well as the high fees, and are bringing the business in-house. This combination of activity is a threat to the traditional banking business of global universal banks like Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, BNP, and Morgan Stanley.