Chapter 12

Banking and Analytics—The PayPal Gang, Palantir versus Alibaba, and Hundsun

In his fascinating book, Who Owns the Future?, Jaron Lanier tells us that the cloud server will soak up everything in its path. It will know where the lowest price is for anything on the planet. It will become a truly global leviathan that will attract the best advertisers. It will learn all about our likes and dislikes. It is learning our price-points and preferences—our credit rating and our sneakiness. It will quantify everything about us. It will learn our skills and try to replace us. Free exchange of information brings insecurity. The server will become cheap to run, and people will remain expensive. We are willingly giving out knowledge to the server for free. We need to get with this server and remain dynamic and imaginative, or else the world has a cruel message: Salaries can seem like unjustifiable luxuries. Those who sit by idly as the cloud server accumulates more and more to itself will lose out: banking, law firms, universities, music, journalists, architecture, and so on.1

So, the new race is the one to dominate the cloud. The cloud is a cosmic rental storage facility for billions of bits of information for thousands of companies. It is an information system that is abstracted from the buyer and is beneficial because it is a variable expense to the buyer of the service.

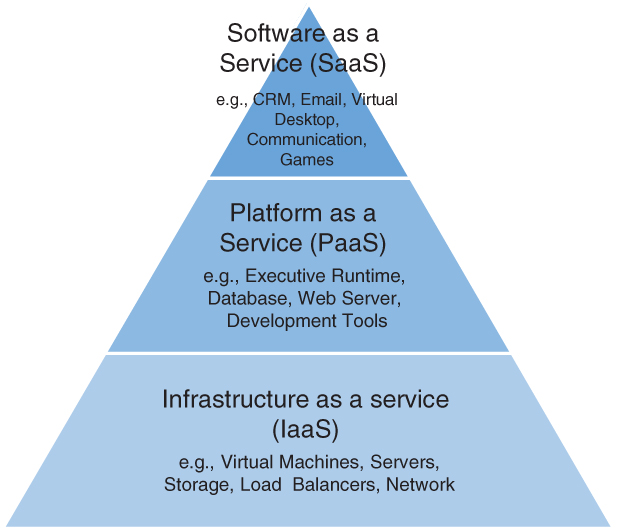

There are three parts of the cloud: infrastructure, platform, and software. Figure 12.1 shows the layout of the industry as it stood in 2014. The software is all about client relationships, desktops management, communications, and e-mail services. The platform is database management, web servers, and development tools. This will be a key element of the whole new industry of credit data management where enterprising financial technology firms will discover efficient ways to distribute capital armed with easily digestible but fantastic amounts of consumer information. The infrastructure is virtual machines, networks, and large servers. In this chapter, I will discuss ways in which large hedge funds, financial institutions, government entities, and security companies use the infrastructure to digest billions of bits of information for pattern-matching, correlations, causality, and sorting of behavior, price-points, preferences, and so forth. This is the realm of the CIA, DIA, NSA, Citadel, Palantir, and high-frequency trading.

Figure 12.1 The Three Types of Cloud Service

This industry is very new—only four or five years old. In one survey from Gertner and Forbes, companies were asked if the use of the cloud was a strategic part of their customer-facing businesses. In 2010, only one in three said yes. In 2013, two out of three said yes. From the second quarter of 2013 to the second quarter of 2014, quarterly revenues for the cloud increased from US$1.2 billion to almost US$2 billion. Seven years ago, there was virtually no revenue from this business. As can be seen in Table 12.1, the biggest player in this is Amazon, with a 50 percent market share. Microsoft has made the biggest inroads in the past year. Its business was up 160 percent in the first half of 2014. IBM and Google are growing quickly as well. Think about it. In 2009, there was only US$470 million in revenues from these companies. In 2013, there was US$6.2 billion in revenue. Even if current rates of growth fall by half, this will be a US$10 billion business within a few years. Trailing these giants is Alibaba's Aliyun (Alibaba's cloud business). It did not even exist in 2009 but saw revenues of US$125 million in 2013. Alibaba is head-to-head with Huawei in this business inside China.

Table 12.1 Annual Revenues in US$ for the Cloud: This Is a Brand New Business

| Estimated Cloud Service Revenue | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

| Amazon (AWS) | 448 | 674 | 1,291 | 2,035 | 3,200 |

| Microsoft (Azure) | 80 | 250 | 1,000 | 2,000 | |

| Google (Cloud Platform) | 314 | 900 | |||

| Alibaba (AliCloud) | 23 | 69 | 83 | 105 | 125 |

| Total | 471 | 823 | 1,624 | 3,454 | 6,225 |

The growth rates for this cloud traffic are astonishing. As expressed in exabytes (10 to the power of 18 bytes or one billion gigabytes), the traffic from 2012 to 2014 doubled. It is expected to double again by 2016. This represents a 40 percent compound growth rate for the period of 2012 to 2016. For the period from 2012 to 2017, Asia is expected to have the fastest growth. This is largely in China. Of this the consumer and business will grow at about the same rate. Asia Pacific is expected to grow from 505 exabytes to 1,900 exabytes by 2017—a fourfold increase. By 2017, it is interesting to note that Asia Pacific is expected to equal North America in exabyte traffic. On this score, let's compare the trends in the United States to the trends in China.

The PayPal Gang Summit: Big Data, Research, Credit Ratings, and Cybersecurity

In the United States, the PayPal gang is busy ramping up the system to a new and stratospheric level of super-powerful data processing of everything that moves. They are working for the government, hedge funds, large banks, and consumer companies. A leading-edge player here—and probably the best example of the future—is Palantir. Founded by Peter Thiel several years ago, Palantir has had explosive growth in the past three years. The initial funding for Palantir came from the CIA. The CIA's venture capital firm is called In-Q-Tel, and it was one of the angel investors. Palantir provides software that can search, cross-reference, and interpret large amounts of data from many sources. Palantir's software has been used to detect fraud and insider trading by law enforcement agencies and banks. Its clients include U.S. government agencies such as the CIA and FBI, Bank of America, J.P. Morgan Chase, and News Corp. In 2013, it had estimated revenues of US$450 million. The current value of Palantir is estimated to be US$9 billion. (Let's also keep in mind that Amazon has a US$600 million contract with the CIA, presumably for international sales, since it is illegal for the CIA to operate domestically.)

Having started as an entity that was funded by the government, Palantir now has 60 percent of its revenues from the private sector. It was surmised that the financial impropriety at HSBC with drug cartels in Mexico was discovered by way of the CIA. It would not be a stretch to think that Palantir might have had a role to play in this investigation.

Palantir's reach is extensive, to say the least. The company now has a right and a left hand. The right hand is Palantir Gotham. This entity analyzes structured and unstructured data (for example, data found in e-mails, news reports, books, and websites) into a single information model providing relationships that can be understood by nontechnical staff. It enables users to Palantir to search multiple large datasets simultaneously to identify relationships. Gotham's clients include U.S. government agencies the CIA and FBI, who use the software to seek patterns in large amounts of data to track terrorists, drug trafficking, and cybercrime.

The left hand is Palantir Metropolis. This entity is the financial services arm and provides powerful quantitative financial analysis software. This software distributes bank data in a centralized fashion to technical and nontechnical users. Customers include banks and hedge funds. As an example, Steve Cohen at Point72 Asset Management (formerly known as SAC capital) hired Palantir to assist in its compliance and surveillance. It has an “Unauthorized Trading” algorithm that assigns riskiness scores to traders by examining correlations between key risk indicators in the context of overall trading activity. Citi uses Palantir Capital Market software to merge proprietary and vendor data into one platform for equity analysis.

Palantir is a cutting-edge company that is taking financial software and big data to new heights. It helps banks manage internal risk. It helps law enforcement monitor the potential illegal activity of financial institutions with regard to violations of money laundering and antiterrorism. It gathers data for hedge funds to help to discover previously undiscovered correlations among social, economic, and commercial phenomena.

It is almost amusing that top executives at Palantir admit that they have trouble articulating what exactly the company does. They say that it “extracts insight from information.” They respond to human-driven queries. They can summarize large datasets, and they visualize datasets by articulating what is going on inside the data. Palantir lauds itself for being able to do the work quickly.

One example of a company that used large data to discover how consumers behave is the following. One company was asked to analyze all of the purchases at Walmart (tens of millions) and find the one common purchase of those that had the best credit rating. Interestingly, the company discovered that people who buy door-stops had the best credit rating. What was the most common purchase of those with the worst credit rating? The deadbeats most often bought mouth restraints for dogs. Is this a matter of mixing up correlation with causation? Maybe, but the experts in big data say without batting an eyelid that when you have millions of data points offering you some fairly sound and compelling correlations, it is folly to ignore these conclusions. In their book called Big Data, Kictor Mayer-Schonberger and Kenneth Cukier make the point that correlations can be found faster than causation and correlation is backed up by millions of data points. He makes the point that we still need controlled experiments with carefully handled data. For everyday needs, however, knowing what—not why—is good enough. In addition, big data correlations can be a harbinger of promising areas in which to explore causal relationships.*

The above is an excellent example of the kind of work that Palantir might do. Also mentioned in Jaron Lanier's book Who Owns the Future? are examples of entities that search the globe thousands of times per second for the lowest price for a certain book. A company like Amazon will use this price (whether it is in Belgium, Biloxi, Beijing, or Bangalore) as a new benchmark and beat the previous price. This is known as a bot. This bot is an algorithmic program that searches for the lowest prices everywhere and at all times. This world of the bot is one where great fortunes are made by driving prices down rather than up. It drives out the middleman and forces out the marginal producer. The curse of humans is that they love getting good deals. (Amazon is an example of a bot gone haywire. It is constantly driving down prices so fast that it seems that this bot is devouring the shareholders of Amazon. The company can't manage to make money after all these years!)

These bots will always only ever get the best deal possible (priceline.com lives by this) but this means that the bot will drive the price of one industrial or social good after the other to something close to free. This is designed to push all prices to the marginal cost of production. So, we must stay close to this powerful server, as it is the arbiter of prices. This is a super-deflationary phenomenon. It learns all it can about our behavior and then it offers all of the services we create at a price that is the closest to free that can be possibly be achieved. If we do not stay near the server and constantly improve innovation and imagination, we are out of a job. Hence the vital importance of companies such as Palantir, Google, Alibaba, and Amazon. Imagine what will happen as these companies hone their skills better in the world of lending. They will eat inefficient and high-cost banks alive!

Credit card companies, new financial technology, and innovative software by companies like Moody's Analytics are also joining this game. They will crunch millions of data points to find good creditors who are down on their luck and need a short-term loan, for instance. They will eventually squeeze out inefficient and high-cost banking entities. One interesting example of a type of high-quality credit is a woman who is almost finished with her nursing degree and needs a loan. She fits a certain kind of criteria of an excellent credit and will be given a loan in less than a day. Companies have created algorithms to track down women like this and offer them loans. The level of detail about who is most apt to pay back a loan from myriad details of our private lives is astounding. Slight changes in our habits are picked up by some of the most sensitive bots out there. These bots can detect divorce, pregnancy, bankruptcy, new additions in the family, changes in health, changes in mood, and other intensely personal details with startling accuracy.

In addition, Palantir has access to all open information platforms of the U.S. government: health, safety, traffic, budgetary items. It is safe to say that Palantir's systems are firmly embedded into the defense, counterterror, intelligence, and law enforcement establishments. It is emphatic that it abides by all civil liberties protections mandated by the federal government. It is safe to say that Palantir's network is something of a foundation for how data collection, integration, and analysis can help financial institutions in the future.

Another competitor is Kaggle. Kaggle has had PayPal veteran Max Levchin as its chairman since 2011. It is a platform that creates competitions for predictive modeling and analytics. Data miners compete to produce the best models for data posted by companies and researchers. Kaggle charges clients a fixed fee and offers monetary rewards to data miners who seek to answer the human queries of Kaggle's customers. In the past few years, Kaggle has paid out more than US$5 million in “rewards” to data scientists who have helped its customers crack a thorny issue or discover important patterns in certain behaviors. Clients include GE, Microsoft, NASA, and Tencent.

Companies like Palantir and Kaggle are important for all financial institutions because they can breathe life into the imaginations of IT teams at banks about how to data mine consumer behavior (e.g., professional development, changing tastes, patterns of purchasing door-stops, etc.) and find better ways to safely and prudently lend money to those who are most likely to repay the money and also to avoid the deadbeats. It's a very simple procedure. And so much of this is automatic. Furthermore, software is getting cheaper by the day, and there is more information available on the Internet on patterns of individual and corporate financial behavior. Banks who do not aggressively embrace this trend are dead in the long run.

I am not saying we are entering into a new Panglossian world of an end to credit problems, thieves, and con artists. We live in a world of alligators and boa constrictors in all walks of life. I am saying that this world in which we have extremely powerful tools to examine and parse data points to more efficiently allocate credit is very likely a better world than the one dominated by banks that time and again have shown their ineptitude when it comes to allocating capital and managing risk.

I am saying that the hardest nut to crack in the world of credit has been the small and medium enterprises that have traditionally been locked out of the credit world. Is there a reason for this? Are small and medium enterprises composed of perpetual liars and thieves? Of course not. Most work very hard to run family businesses and are honest people. But banks have traditionally not had the economies of scale to make money on this sector when they can make better money on big-ticket, high-margin, low-touch loans to large corporations and governments.

In a world of immense data that can be easily managed among and between the banks and the company, there are many ways to open up credit to hundreds of thousands of SMEs. If an SME is a true partner to a bank and offers its data on working capital, inventories, tax, and payroll, the bank can offer not only more credit but also better pricing for this credit. This is a revolution right in front of our eyes. And it is real. Just ask people who bank with Commonwealth bank of Australia. This bank is making this a reality now. And companies tell CBA that the software offered by CBA helps them to know their company better.

One last comment. There is a predilection for some strange reason to pooh-pooh the idea of financial technology as a scam or a passing phase—some adolescent idea that will fade away. I think this is a misplaced notion. I sense that there is powerful momentum and a kind of irreversibility about this. I strongly believe this will only grow larger. And regulators, users, governments, and banks need to get their heads around this sooner rather than later. To ignore this trend as a passing phase is foolish and costly.

Alibaba's Cloud Business: The Future of Banking

We go to the other side of the world and see that, in China, Alibaba is doing precisely this. It is aggressively morphing from a company that is a combination of PayPal, eBay, and Amazon into a company more like Palantir and Google. Alibaba is achieving this through a number of smart moves that may create one of the most interesting hybrid companies the world has ever seen. Alibaba not only looks like Amazon but also has shades of Palantir and resembles the entertainment element of Disney. So, Alibaba is morphing into a four-headed creature in e-commerce, entertainment, banking, and information analysis.

The bread-and-butter of Alibaba is the equivalent of Amazon and eBay. Alipay is a separate entity but is similar to PayPal. It is likely to list inside China and have an H share listing in Hong Kong in 2015. Like PayPal and eBay, it is probably wise to have a separate listing. This will allow it to have a higher valuation, and they are in fact different businesses and belong apart.

Alibaba is gluing other interesting entities onto this framework that revolve around consumer behavior: driving, dating, learning, fun, languages, lifestyle, and buying goods that can be mailed by Alibaba to the home. Figure 12.2 shows how Alibaba is becoming a lifestyle company. This diagram shows how Alibaba is already like Google, Dropbox, eHarmony, Amazon, Twitter, Spotify, Orbitz, Uber, and ING Direct.

Figure 12.2 Alibaba Knows Everything about 500–600 Million Chinese

Source: Adapted from Quartz

AliCloud and Hundsun: The Mother Lode of All Financial Data

There is something else going on with Alibaba, and the other part of this entity that is less understood is more like Google and Palantir and less like eBay and Amazon. Alibaba has built its own cloud server from scratch and called it Aliyun. This is very important, because Alibaba decided to build all of its infrastructure internally with no outside entities. This is referred to as a “No IOE” policy. In other words, the technology that Alibaba used to build the infrastructure is not from Intel. It is not from Oracle. And it is not from EMC. It is, indeed, indigenous technology built internally.

There is an element of paranoia here—justifiable paranoia, that is. The Snowden leaks of NSA material showed that everything is open to the U.S. government.2 The NSA reads just about anything and has cracked any code there is. Governments from China to Germany are now aware of this. So, countries like China that are overcoming a century of humiliating occupation (at one point in the early 1900s, China was occupied by 12 different countries) are flexing their nationalist muscles and saying they do not want any cyberimperialism. This is understandable and expected. China has a very capable spying service, which is very likely on a par with the NSA. It wants to preserve its secrets from the prying eyes of the U.S. government. So, it has concluded that it will build its own technological architecture. Furthermore, we shall see that the phenomenal technological firepower achieved by the likes of Palantir has scared China into creating its own equivalent.

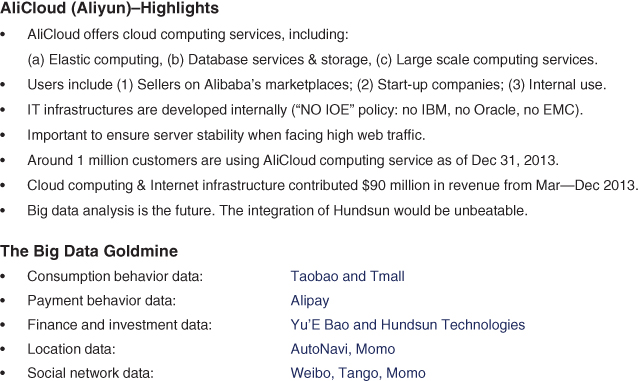

Since its establishment only a few years ago, AliCloud (Aliyun) has more than one million customers and it has generated almost $100 million in the three quarters to December 2013. Cloud computing and Internet infrastructure are a powerful combination. See Figure 12.3. With Taobao and Tmall, Alibaba has access to the spending habits and price-points of hundreds of millions of Chinese people. With Alipay, Alibaba has access to the credit histories of hundreds of millions of people in literally thousands of cities across the country. With the dating service called Momo, Alibaba has access to preferences and demographic information of 140 million adults in nearly every city in the country. And with Weibo and Tango, Alibaba has access to a social network that makes Facebook pale in comparison.

Figure 12.3 Alibaba Sees under the Skirt of All Chinese Financial Institutions

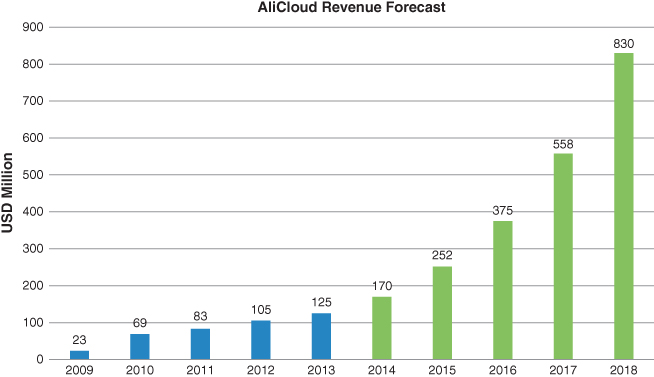

Inside China, the cloud market is growing at more than 40 percent per annum and now accounts for only 3 percent of the global cloud market. In this space, Alibaba has a commanding share. Tencent, Shanda, and Baidu are all competing in this market. But the real competition here comes from Huawei. Huawei is the gargantuan technology company founded by a PLA Army colonel. Think of IBM, GE, and Apple all in one company! Huawei is the real competition for Alibaba in this space. Time will tell just where this competition goes. So far, the software infrastructure is 70 percent of the market. Infrastructure is about 20 percent of the market. In the software sector, Alibaba is the dominant player. In effect, then, Alibaba commands the field in the first inning of this buildout. Estimates show that this business will be close to US$1 billion by 2018.

AliCloud's customers are remarkably diverse. Customers include companies in pharmaceuticals, utilities, government security, tourism, weather trends, near-field communication mobile support, gas distribution, telecom, and IT solutions. It is basically the entire economy located inside the AliCloud. And this is only three years old. Imagine what will come next! (See Figure 12.4.)

Figure 12.4 Beware the AliCloud—It Will Grow Like a Weed

Source: Schulte Research, Alibaba

What's next is Sesame! Sesame is Alibaba's new credit rating service for consumers. In the United States, 85 percent of people have some form of credit rating through a Social Security card, credit cards, phone data, sensor data, or browsing data. In China it is only about 25 percent. This is only 350 million. Alibaba's ambition is to have reliable credit ratings on all Chinese over the age of 14 fairly soon, so even youngsters can have cellphone accounts or credit cards for school or other purposes. The numbers being thrown around so far are in the neighborhood of 900 million people who could conceivably have reliable credit ratings and be able to get credit. So, a company like Alibaba (whose market share in phone e-commerce is more than 80% and whose market share in peer-to-peer e-commerce is 90%) can realistically hope to achieve these ambitions. Imagine a world where a company like Alibaba or Tencent could have reliable credit data on 15 percent of the earth's population. This is precisely why Alibaba needs AliCloud. In this way, we should conclude that Alibaba will become the world's largest ratings agency within three years.

Hundsun: A Vast Array of Information on Financial Services

Now we arrive at the mother of all information lodes. In a brilliant move, Jack Ma bought a controlling interest in a company called Hundsun. Hundsun was developed by 12 software engineers in the 1990s. The 12 sold their 22 percent interest to Jack Ma's personal company Zhejiang Rongxin for US$522 million. Because this investment involves sensitive technological infrastructure for the banking sector, banking laws prohibit foreign ownership; this is why Hundsun lies in the private company rather than inside the listed entity. The remaining 78 percent of the company is listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange and its ticker is 600570. The Ministry of Commerce sanctioned the deal in late 2014, so the relationship has been cemented.

Hundsun is a unique company. Imagine a company that is like IBM and Cisco and that has built the infrastructure for PIMCO, Fidelity, J.P. Morgan, Prudential, and Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Presumably a good portion of this information will end up being stored in Alibaba's AliCloud. If we combine the industries for which Hundsun has built the backbone, it runs the full gambit of financial services. These include securities, banking, asset management, insurance, treasury management, and exchange solutions. And it also includes the infrastructure for the new derivatives markets in China, including futures and options markets that were just opened in early 2015.

Hundsun also has a great deal to do with internal security for China. For instance, like Palantir, it also is involved with anti–money laundering, internal compliance platforms for banks, and internal controls for trading. But it also serves functions akin to exchanges like NASDAQ. Hundsun has built the backbone for the futures and options exchanges to be launched in 2015. It also operates systems that manage fund sales, margin accounts, and security exchange platforms. As a result of the integration of these tools in the Alibaba arsenal, Table 12.2 shows the raw data that can be analyzed inside the AliCloud to discover where people shop, how they drive, what they buy, how much they want to spend, where they travel, how they insure themselves, when they will buy a house, how they want to entertain themselves, and what they want to learn about and read.

Table 12.2 Alibaba Information Powerhouse Is the Entire Consumer Spectrum

| The Alibaba Powerhouse Combines: | |

| E-commerce: | Home, clothes, health, books, beauty, weddings, school |

| Travel: | Plane, hotel, car, boat, train information |

| Banking Data: | Liquidity, portfolios, insurance, working capital, inventories |

| Alipay: | Habits, trends, lifestyle, demography, warning signs |

| Big Data: | Personal, corporate transactions, credit ratings |

| Financials: | Futures, options margins accounts, |

| Entertainment: | Crowdfunding of shows, films, music, streaming |

There really is no one company like it in the world. This company can conduct human queries on just about anything. How many insurance policies are there? How many miles did Chinese people drive last year, and where? What kinds of movies do people want to see? Where do people want to go on vacation? What kind of analysis do investors in equities and fixed income like to use? How do Chinese construct portfolios for their future? Who needs to get rid of certain inventories? Who is a good credit and needs working capital for 90 days? In what way will Chinese use the futures and options markets? This is a unique and massive amount of data on the largest population in the world, and it is generally closed. But this is just getting started! Perhaps most important of all: What if companies like Alibaba, Palantir, and Tencent are able to more accurately predict GDP trends better than any government entity?

Think about this further. Look at Figure 12.5. It shows the power of the information that is part of the Hundsun infrastructure built over the past several years, which conceivably (and in all likelihood is part of Alibaba's cloud) will now be able to be mined by Alibaba entities. If one sees corporate transactions going on live, it is possible to get a good real-time sense of where GDP is going. It is possible to get an up-close-and-personal sense of consumption trends, entertainment likes and dislikes, and fund flows within the economy. It will be possible for government entities to track corrupt officials and their cash movements. It will be able to seek out money laundering. It will be able to have a reliable sense of funds flows among and between various asset classes. The opportunities for data analysis (for better and for worse) are infinite.

Figure 12.5 Hundsun Built the Backbone Connecting Banks with Consumers

Final Analysis: There is No Such Thing as Private Information for Anyone

What we are seeing in front of us with Alibaba on the one hand and Palantir/Amazon/Google on the other is the largest and second largest economies in the world competing for data hegemony. Both of these entities are indisputably joined at the hip to the government of their respective countries. When I was traveling around the world presenting my clients with a bullish analysis of Alibaba in the fall of 2014, I was asked a perplexing question. Some investors asked whether it bothered me that Alibaba was so closely entwined with the Chinese government. When I laid out the intimate connection among and between Google, Amazon, Palantir, and the U.S. federal government, there was a sheepish silence. This is because there is an inbred bias that China is the only country that watches and controls its people. There is a sense inside the United States that government intrusion into people's lives in minimal and lies within constitutional protections. If the Snowden files taught us anything, it is that the government can issue hundreds of thousands of warrants on e-mail and messages under the guise that a crime might happen. Almost none of these are contested. Some would say this is a violation of the Fourth Amendment, which concerns illegal search and seizure.

One thing is certain. There is no way that Jack Ma and Alibaba would be able to do what they are doing without the tacit consent of the government and the military. In addition, it is certain that Jack Ma is present in meetings when the People's Bank of China discusses any issue of financial technology with the banks. Similarly, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Palantir are absolutely joined at the hip with the political and military structure in Washington, D.C. I mentioned the US$600 million contract that Amazon has with the CIA. In addition, Palantir received money for its start with funding from the CIA's private equity arm.

Another sticky wicket for both of these entities (Alibaba and Silicon Valley quasi-banking activity) is the inevitability of regulation. History shows us that regulation almost always arises out of abuse. Fires in shabby textile mills that killed young girls in Manhattan in the early 20th century brought about modern fire codes. A bursting dam in Pennsylvania in the late 18th century brought about safety codes for infrastructure. The Depression in 1929 brought about the Securities Act of 1934. The calamity that was the great recession of 2007 brought forth the 13,000-page Dodd-Frank Act. The admittedly nascent financial technology industry has not crossed the line or committed any large-scale fraud of serious crime—yet. It is inevitable that this will happen. So far, however, these people are the new “respectable” crowd to be seen with and to receive political contributions.

The number-one problem I see for this industry is not a shortage of ideas, money, or smart entrepreneurs. It comes from conservative regulators who lack the imagination to see that a great trend has begun that is virtually unstoppable. Those who let it take its course will prosper and develop rapid sophistication and wide acceptance. China and the United States are examples of this. Those who prevent this from happening will cause their financial systems to remain backward and inefficient, full of bloated, unprofitable, and inefficient banks. Joseph Tsai, vice chairman of Alibaba, said that the financial services industry in China was “very antiquated” and that e-commerce could help to reform and develop the current system. With Alibaba, Tsai asserted that the economy could “shift from one focused on the state to one focused on the consumer.”3 On the other hand, he admitted that there had already been setbacks. One example he mentioned was the suspension of the ongoing rollout of the online money market fund Yu'e Bao. Another was the central bank's decision to block plans for a virtual credit card. Why? This would hurt the state credit card monopoly Union Pay. One has the feeling, though, that reform is high on the agenda in China and that Union Pay will need to give way or get more efficient. China is not messing around here. It is trying to create a technological infrastructure that is as good or better than that of the United States.

The elephant in the living room here is the censoring of information. Gmail is blocked all over the country. Bloomberg only partially works. Sites are regularly shut down. There are hundreds of words and phrases that are immediately shut down when they appear on the Internet. An army (literally) of people regularly monitors millions of messages and deletes those it deems inappropriate to the political elite. This has to change. How can Shanghai possibly become a financial center if Bloomberg, Gmail, and other vital messaging systems do not fully function? A free flow of information is vital. China is a long way from this. Something will have to give. The Chinese government has great insight by letting companies like Alibaba and Tencent do what they are doing. But there is a new political cold blast blowing through China that is a reaction to the runaway corruption of the 2009–2012 years. Ideological purity and a vicious anticorruption campaign are sweeping through the country (which in my opinion is long overdue and necessary). China needs to balance progress in technology with both political stability and ongoing credibility of the Communist Party.

As it is now, the development of the technological infrastructure in China is on a par with most of the OECD and it has done this in a very short period of time. Interestingly, Alibaba has done in seven years what six or seven companies in the United States have taken 15 years to achieve. Alibaba is eBay and it is Google and it is Amazon, and Uber, and eHarmony, and ING Direct. I think we should all watch next what Alibaba does in the distribution of pharmaceuticals within China. More importantly, I think the industry that Alibaba will dominate is the streaming of films. Alibaba has hooked up with both Sony and Lionsgate to distribute content in China. This may spell the end of cable within a few years as more movies are watched through Internet streaming and as new technologies enhance the experience of watching movies using a phone that can display the image on a wall as a projector or in a 360-degree experience.

The possibilities are endless and the competition is intense. But companies like Alibaba, Palantir, Google, Apple, and Amazon are first movers and have phenomenal cash piles to dominate any subsector they choose to enter. One chart to show the way in which industries can be overturned by rich and entrenched first movers is the way in which Apple is stretching its wings in many different areas. Figure 12.6 shows what can happen if Apple decides to get into the credit card business with Apple Pay. It can disintermediate many companies and become a middleman among cards companies, merchants, banks, and the consumer.

Figure 12.6 Apple Was Alone 7 Years Ago and Now Connects All with Its 700 Million Users

Source: Adapted from Goldman Sachs

Facebook will increasingly be used as a source of financial technology to raise money, transfer funds, settle accounts, pay bills, and other activity. Alibaba will become more like Disney and less like eBay. Facebook may become more like a multicultural virtual financial center where finance, buzz, brilliant marketing, and the “experience” can create “virtual” industries overnight. Airbnb will challenge hotels in every country in the world. Uber will change how we all get taxis in countries all over the world. Intuit, Kabbage, and Indinero are companies that will change how small and medium companies raise money. Prosper, Kickstarter, and Zopa will alter how people fund projects. Palantir will change the way we understand the mining of data. Banks will struggle to keep up with this phenomenon, but I am not hopeful. The cloud server is the center of this. We need to take heed of the advice of Jaron Lanier: “People who want to do well, as information technology advances, will need to double down on their technical education and learn to be entrepreneurial and adaptable. For information and money are mutable cousins.”4

This book is intended to offer a roadmap to provide for those in the financial industry (individuals, brokers, information providers, and banks) a way to understand where this revolution in information and financial technology is going. The cloud server—and the billions of bits of information on it, which includes detailed financial behavior of billions of people—is where we are all being drawn toward. The closer we get to it and the better we understand it, the better our chances of not being left behind in a world of economic feudalism and ultimate poverty. One of the more conservative financial institutions in the world is the Bank of England. Andy Haldane is the executive director of financial stability. He recently said: “Banking may be on the cusp of an industrial revolution, the upshot of which could be the most radical reconfiguration of banking in centuries.”5 To say that we may be on the cusp is a profound understatement. The revolution has started. As usual, those most affected by the revolution—the banks themselves—do not seem to see it coming. Hannah Arendt said that revolutionaries are those who see power lying in the street and pick it up. Thousands of entrepreneurs are picking up capital, information analytics, raw material for corporate and individual credit scores, as well as good management off the streets and are now creating a new banking industry. It is always a bottom-up operation, and only ever starts at the periphery. It is a bare-knuckles fight between the future and the past. Between the traditional bankers of the past and the financial technology innovators of the future, I know whom I will bet on!