Chapter 4. Finding and Installing Ubuntu Applications

![]() Using the GNOME Software Center

Using the GNOME Software Center

![]() Learning Terminology and Foundations

Learning Terminology and Foundations

![]() Useful Software Packages to Explore

Useful Software Packages to Explore

![]() Playing to Learn with Educational Programs

Playing to Learn with Educational Programs

In addition to those applications installed by default, Ubuntu offers a wealth of other applications to help you make the most of your computer. Different people use their machines in different ways, and it is for that reason that we wanted to help you discover how to enable your Ubuntu computer to do even more.

Chapter 3 included a brief introduction to the GNOME Software Center as one way to install or remove software. In this chapter, we cover this approach and other methods as well. Work done using one tool to add or remove software is recognized by the related tools, so it is okay to mix and match which ones you use.

Additionally, we show you just a few of the thousands of additional applications that you can install on your Ubuntu system. Each section showcases one application, starting with the name of the package you need to install and the various Windows/OS X equivalents that might exist.

Using the GNOME Software Center

Like other tools discussed later in this chapter, the GNOME Software Center installs programs from the online Ubuntu software repositories.

To launch the GNOME Software Center, click the Dash icon in the Launcher at the left of the desktop. In the search box at the top of the menu that appears, type Software and the search will begin automatically. Click the Software icon that appears in the box. When it runs for the first time, and occasionally afterward, it will take a few moments to initialize itself and the list of available and installed applications. Once this is complete, you will see the main screen shown in Figure 4-1.

We introduced the basics of the GNOME Software Center earlier in Chapter 3. Let’s look at some of the other aspects now.

Sorting

Click a category name at the bottom of the GNOME Software Center window to sort the listed packages by category. Some of them are further broken down into smaller subcategories, such as the Games listing shown in Figure 4-2. Note that books and magazines are now available instantly in their digital format via the application.

Searching

Type search terms in the search box at the top center of the window to find related software. The search conducted is a live search, meaning that the results are updated as you type; you do not have to press Enter first, and you can change the terms and get new results as they load, as in Figure 4-3.

Learning More about a Package and Installing It

Click the package name, icon, or description to learn more about the package. You can click Install to install the software. There is also a Web site button, which opens the software developer’s Web site, giving you easy access to more information to assist you in making your decision. Further information about a package—the specific version of the package, its size and license, and more—is included below this and just above the Reviews section.

Scroll down to read reviews and ratings, if any have been posted for the package (Figure 4-4). You write your own review by clicking on the button labeled Write a Review.

Removing a Package from the GNOME Software Center

If you decide that you no longer want an installed package, just search for it using the search bar. Once you find its listing, click on the Remove button, located next to the package’s description, remove the package from your computer.

No-Cost Software

The software available from the GNOME Software Center is free, in terms of the cost and the code that is available for people to view, modify, and edit. You pay nothing for this software, and it is completely legal for you to copy it, use it, share it, and so on.

Learning Terminology and Foundations

Learning the meaning of a few terms will help you better understand how the software gets installed on your machine as well as how the system works.

![]() APT: Advanced Package Tool (APT) describes the entire system of online repositories and the parts that download them and install them. The APT is not highly visible when using graphic interface–based systems like the GNOME Software Center, but it is very obvious when you are using command-line tools like apt-get (described in greater depth in Chapter 8). Whether you use a graphical interface or the command line to deal with Ubuntu software packages, APT is at work.

APT: Advanced Package Tool (APT) describes the entire system of online repositories and the parts that download them and install them. The APT is not highly visible when using graphic interface–based systems like the GNOME Software Center, but it is very obvious when you are using command-line tools like apt-get (described in greater depth in Chapter 8). Whether you use a graphical interface or the command line to deal with Ubuntu software packages, APT is at work.

![]() Repositories or software channels: In the Ubuntu world, these giant online warehouses of software are divided between official Ubuntu repositories and unofficial ones.

Repositories or software channels: In the Ubuntu world, these giant online warehouses of software are divided between official Ubuntu repositories and unofficial ones.

![]() Packages: Applications are stored in packages that not only describe the program you want to install, but also tell your package manager what the program needs to run and how to safely install and uninstall it. This makes the process of dealing with software dependencies smooth and easy for end users.

Packages: Applications are stored in packages that not only describe the program you want to install, but also tell your package manager what the program needs to run and how to safely install and uninstall it. This makes the process of dealing with software dependencies smooth and easy for end users.

![]() Dependencies: Dependencies comprise the software that is needed as a foundation for other software to run. For example, APT is needed for the GNOME Software Center to run, because the APT takes care of many of the details behind the scenes.

Dependencies: Dependencies comprise the software that is needed as a foundation for other software to run. For example, APT is needed for the GNOME Software Center to run, because the APT takes care of many of the details behind the scenes.

Using Synaptic

Synaptic is a powerful graphical tool for managing packages. It is not installed by default. While the GNOME Software Center deals with packages that contain applications, Synaptic deals with all packages, including applications, system libraries, and other pieces of software. Changing the system on this level is more complicated but also allows you to exert more detailed control. For instance, you can choose to install a specific library if you need it for a program that is not available in a package format.

Synaptic may be installed from the GNOME Software Center and then found by searching in the Dash for Synaptic Package Manager. Launch it and you will see the main window, as shown in Figure 4-5.

Installing a Package

As with using the GNOME Software Center, installing packages with Synaptic is fairly easy. You can browse through the package list and click on the package name to expand its description. You will be able to see it in the box located at the bottom of the Synaptic window. After you find the package you wish to install, click the checkbox to the right of the name of the package and select Mark for Installation. A dialog box may pop up (Figure 4-6) showing you which dependencies (if any) need to be installed; you can accept these dependencies by clicking the Mark button. After you have selected all the desired packages, click Apply on the Synaptic toolbar to begin installation.

Removing a Package

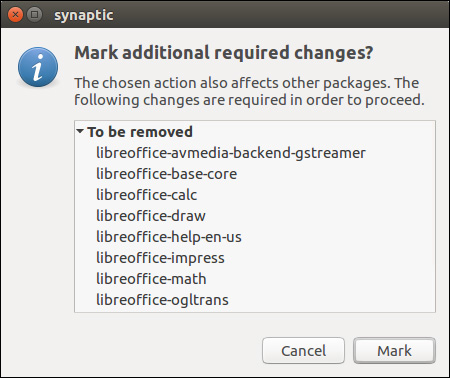

To remove a package, click on the box next to the name of an installed package, and choose Mark for Removal. As with installing a package, you may be asked to mark additional packages for removal (Figure 4-7). These are generally packages that depend on the presence of the main package you are marking for removal. If you wish to remove all the configuration files as well, choose Mark for Complete Removal. Bear in mind that if you decide to reinstall the package at a later date, your settings will not be saved, as all the configuration files will be reset. After you have selected the package(s) you wish to remove, click Apply on the toolbar to start the process of removing the package(s).

Finding That Package

So you are looking for a package but don’t know where to start? Just click the Search button on the toolbar and enter the search term. By default, the regular search looks at both the package name and the description, but it can also search just by name or a number of other fields.

If you know the section where the package is found, select it in the left pane (you may need to go back to the Sections pane). Select the button in the lower-left corner labeled Sections, and browse through the packages in that section.

In addition to Sections, other package listing and sorting options are worth exploring. You can access them using the buttons at the bottom left of the Synaptic window. Status lets you sort according to installation status. Origin sorts according to the repository from which the software was installed (or no repository for manually installed software; see the section later in this chapter on installing software that is not in a repository). You can even create custom filters to aid your search.

Useful Software Packages to Explore

The software discussed in this section of the chapter is not installed by default but is known to be useful and well respected. These packages are identified here as recommendations to help those users who have specific needs narrow their search for programs that meet their requirements.

Creating Graphics with GIMP and Inkscape

GIMP

Package name: gimp

Windows equivalent: Adobe Photoshop or GIMP

The GNU Image Manipulation Program, affectionately known as GIMP to its friends, is a powerful graphics package. GIMP provides a comprehensive range of functionality for creating different types of graphics. It includes tools for selecting, drawing, paths, masks, filters, effects, and more. It also includes a range of templates for different types of media such as Web banners, different paper sizes, video frames, CD covers, floppy disk labels, and even toilet paper.

GIMP has a separate set of toolbars that appear above the application’s workspace when the application is opened. This can be a little confusing at first for new users—especially those used to Photoshop. If you want the toolbars to be docked in the workspace, you can go to Windows > Single Window Mode. This mode can help you become more familiar with the GIMP tools. To get you started, let’s run through a simple session in GIMP.

An Example Start GIMP by searching for it in the Dash.

When GIMP loads, you will see a collection of different windows, as shown in Figure 4-8.

You now have two windows. The window on the left in Figure 4-8 is the main tool palette. This window provides you with a variety of tools that can be used to create your images. The window on the right provides details of layers, brushes, and other information. GIMP provides a huge range of windows that are used for different things, and these are just the two shown by default.

To create a new image, click File > New. The window shown in Figure 4-9 will appear.

The easiest way to get started is to select one of the many templates. Click the Template combo box and select 640 × 480. If you click the Advanced Options expander, you can also select whether to use RGB or grayscale with the Colorspace box. You can also choose a background fill color or having a transparent background.

Click OK, and you will see your new image window (Figure 4-10).

To work on your image, use the tool palette to select which tool you want to use on the new image window. Each time you click on a tool in the palette, options for that tool will appear at the bottom half of the palette window.

When you click the button that looks like an “A” in the toolbox, it selects the text tool. At the bottom of the toolbox, you will see the different options. Click the Font button that looks like an uppercase and a lowercase case “A” (like “Aa”) and select the Sans Bold font. Now click the up arrow on the Size box, and select the size as 60 px. Move your mouse over to the empty image window, and you will see the mouse pointer change to a text carat. Click in the image, and a box pops up in which you can enter the text to add to the image. Type in “Ubuntu.” With the text entry still open, click the up arrow on the Size box so the text fills most of the window. As you can see, you can adjust the text while it is in the image. When you are happy with the formatting, click Close on the text entry box. Your image should resemble Figure 4-11.

Now, in the toolbox, click the button that has a cross with an arrow on each end. You can use this tool to move the text around. Click the black text, and move the mouse. Let’s add an effect filter. GIMP comes with a wide variety of built-in filters. You can access these by right-clicking the image and selecting the Filters submenu.

For our image, right-click the image and select Filters > Blur > Gaussian Blur. In the Horizontal and Vertical boxes, select 5 as the value. Click OK, and the blur is applied to your text. (Anything in GIMP can be undone by clicking Edit > Undo or typing Ctrl-Z.) Your image should now look like Figure 4-12.

Now we will create another layer and put some text over our blurred text to create an interesting effect. If the Layers window isn’t open yet, open it with Windows > Dockable Dialogues > Layers. The Layers window will appear.

Layers are like clear plastic sheets that can be stacked on top of each other. They allow you to create some imagery on one layer and then create another layer on top with some other imagery. When combined, layers can create complex-looking images that are easily modified because you can edit layers individually. Currently, our blurred text is one layer. We can add a new layer by clicking the paper icon in the Layers dialog box. Another window appears, in which you can configure the new layer. The defaults are fine (they create a transparent layer that matches the size of your image), so click OK. Next double-click the black color chip in the toolbox window and select a light color. You can do this by moving the mouse in the color range and then clicking OK when you find a color you like. Click the text button from the palette and again add the “Ubuntu” text. When the text is added, it will be the same size as before. Use the move tool and position it over the blurred text. Now you have the word “Ubuntu” with a healthy glow, as shown in Figure 4-13.

The final step is to crop the image to remove the unused space. Click Tools > Transform Tools > Crop, and use the mouse to draw around the “Ubuntu” word. You can click in the regions near the corners of the selection to adjust the selection more precisely. Click inside the selection, and the image will be cropped.

To save your work, click File > Save, and enter a filename. You can use the Select File Type expander to select from one of the many different file formats.

Further Resources If you want to investigate other capabilities found in GIMP, a great starting point is GIMP’s own help function. It is not installed by default, but if you are connected to the Internet, the help viewer will download it automatically. You can also install it by searching for gimp help in the GNOME Software Center. GIMP’s own Web site (www.gimp.org) has all the help plus tutorials and more.

Inkscape

Package name: inkscape

Windows/OS X equivalents: Adobe Illustrator, Adobe Freehand, Inkscape

Inkscape is also a drawing and graphic creation tool, much like GIMP, but one that has a slightly different focus. Unlike GIMP, which works with raster graphics, Inkscape is a vector drawing tool. This means that rather than using a grid of pixels, each assigned a color, drawings are mathematically described using angles and arbitrary units.

To get started with Inkscape, launch it by searching for it in the Dash. Very shortly you will see the default window with the basic canvas of either Letter or A4, with the default depending on where in the world you live. At the top of the screen, below the menus, are three sets of toolbars. The topmost contains common tools like save and zoom, the second pre-sents a series of snapping options, and the third’s content changes depending on the tool selected.

All the tools are listed on the left-hand side of the menu, starting with the selection tool and running down to the eyedropper or paint color selector tool. Let’s get started by drawing a simple shape and coloring it in (Figure 4-14).

First, select the rectangle tool on the left, just below the zoom icon. Draw a rectangle anywhere on the screen. Now let’s change the color of the fill and outside line or stroke.

With your rectangle still selected, right-click and select Fill and Stroke. Over on the right, you will see the window appear, with three different tabs: Fill, Stroke Paint, and Stroke Style. Let’s fill that rectangle with a gradient from orange to white. Immediately below the Fill tab, change from Flat color to Linear Gradient (Figure 4-15).

Look back at your rectangle and see the gradient and a new line running horizontally across the rectangle. Moving either the square or the circle allows you to define where the gradient starts and stops. To change the colors, click the Edit... button. Once the Edit dialog appears, each end of the gradient is called a stop and can be edited separately (Figure 4-16).

Now that we have a rectangle, let’s add some text to our image. Select the Text tool, which is found near the bottom on the left, and click anywhere. A cursor appears, and you can start typing. Type “Ubuntu.” Next we will change the color and size of that text. Let’s make the text 56 point; this size can be selected in the upper right, beside the Font name.

The Fill and Stroke dialog should still be open on the right, but if it isn’t, reopen it. Change the text color to Red, and then choose the selection tool again. Drag a box around both the text and the rectangle, and you should see both selected (Figure 4-17).

Next open the Alignment dialog, which is found near the bottom of the Object menu. Like the Fill and Stroke dialog, it appears on the right-hand side. To center the text in the box, locate the middle two icons with a line and some blue lines on the side of them. Click both the Horizontal and Vertical alignment options, and both the text and image will be centered on the page (Figure 4-18).

Now that you have created an image, what can you do with it? By default, Inkscape saves files in the SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics) format, an open standard for vector graphics. If you want to take your work elsewhere and display it on another computer or print it, Inkscape can also save the file in the PDF format. If you choose to turn the image into a PDF file, make certain you also save a copy as an SVG so you can edit the image later if you wish. Both SVG and PDF are options in the Save dialog. One key advantage of using the PDF format is that it embeds fonts and graphics, meaning your image will look the same on nearly any computer you show it on. You can also export your image as a PNG file for embedding in a text document or uploading to the Web. Many modern Web browsers such as Firefox and Chrome can also display SVG files directly, although most don’t support the full SVG standard. To export your image, choose File > Export, which allows you to decide whether to export just the objects selected, the whole document, or some portion of it. At the point, you have seen just how powerful Inkscape can be. There are many more things you can do with Inkscape, so play around with the various options, dialogs, and shapes.

Further Resources If you want to investigate other capabilities found in Inkscape, a great starting point is always Inkscape’s own help, which is in SVG format, so you can see how the original authors created the tutorials. Inkscape’s Web site (http://inkscape.org) has some great tutorials and articles. If you want a book, Tav Bah’s Inkscape: Guide to Vector Drawing Program, third edition, is a good place to start.

Desktop Publishing with Scribus

Package name: scribus

Windows equivalents: Adobe InDesign, Scribus

For more powerful document creation than is possible with LibreOffice, Scribus is just the ticket. A desktop publishing application, Scribus is built for designing and laying out documents of various sizes and sorts. As such, it makes a few different assumptions that might catch you off-guard if you typically use LibreOffice to create your documents.

When you first launch Scribus, it asks you which kind of document you want to create or whether you want to open an existing document. Let’s create a single-page document and take Scribus for a spin (Figure 4-19).

The first thing to remember about Scribus is that it is a desktop publishing program—which means it is not designed for the direct editing of images and text. Ideally, you will edit and create your images in applications like GIMP or Inkscape and your text in word processors like LibreOffice and then import them into Scribus.

For starters, let’s create a pair of text frames. For our example, we will use a document found in the Welcome_to_Ubuntu.odt file. To create a text frame, you use the Insert Text Frame tool, which is found near the middle of the toolbar. After you draw the text frame, you need to add text to it. Right-click on the frame and choose Get Text. A dialog very similar to the Open dialog appears. Choose the Welcome_to_Ubuntu.odt file, and then select OK. You will be asked a few options; for now, accept the defaults. You should see the text appear on the screen (Figure 4-20).

As you can see, the text overflows the frame. To ensure that the rest of the text is visible, you need to create another text frame and then link the two text frames, allowing the overflow to appear in the second frame. Go up to the toolbar again, select the Insert Text Frame, and draw another frame roughly on the bottom of the page. Then select the first frame and choose the Link Text Frames icon on the toolbar; this icon looks like two columns with an arrow between them. Next click on the second text box. An arrow should appear and, more importantly, your text should now flow from one frame to the next (Figure 4-21).

Next let’s insert an image at the bottom of the screen. As with text, you need to create an image frame and then add the image to that frame. Draw the image frame below the two text frames, and then right-click and choose Get Image. Just as in the text import step, choose your file—this time an image file—in the Open dialog, and it will appear in the frame. Let’s choose the Ubuntu logo, which is found within the Logo folder in Example Content. It will appear in your image frame (Figure 4-22).

Now that you have added some text and an image, let’s export your creation to PDF so you can share it with the world. On the toolbar near the left-hand edge, you will see the PDF logo, just to the left of the traffic light icon. Select that, and ignore the error message about the DPI of the image. Select Ignore Errors, and you will see a large dialog with many options for embedding fonts and the like. Don’t worry too much about them right now, as the document you have created isn’t that complicated. Choose a good name for your document, and then save it to your Documents folder.

Now let’s take a look at your creation in the Document Viewer. Open the File Manager and load your new document (Figure 4-23).

Now let’s go back to Scribus and save the image in Scribus’s own SLA format so that you can edit it later if you wish. Enter the name you chose for the PDF file and save it in the Documents folder as well. You have now created your first document in Scribus. There is a lot more to explore, so go and try things out. Just remember to save every now and again.

Further Resources As always, Scribus’s own help is a great place to start your investigation of this program’s other capabilities. The Scribus Web site (www.scribus.net) has a help wiki, further documentation, and more. There is also an official book, which isn’t out as of this writing but should be very shortly. Information about it can also be found on the Scribus Web site.

Editing Videos with OpenShot

Package name: openshot

Windows Equivalents: Final Cut, Adobe Premiere

OpenShot is an excellent video editor for your home videos. It has a simple to understand user interface, so why not give it a try now?

Go to the Dash and search for OpenShot. Once it has loaded, you are free to start your project.

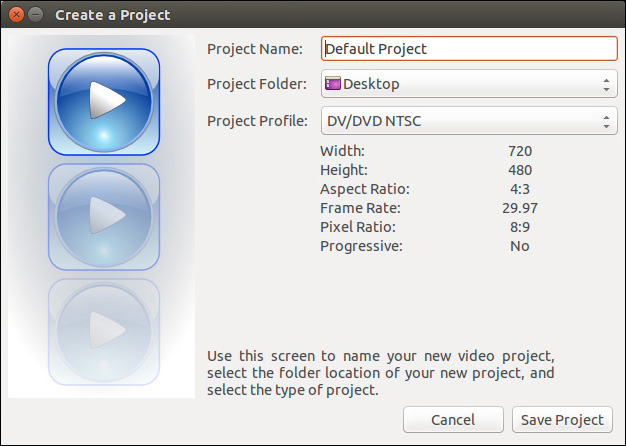

To begin, go to File > New Project; a box titled “Create a Project” will appear. Change the title from Default Project to any name you would like. Now click Save Project, and the project box will close.

At this point, you have several options from which you can choose. The most common practice is to import a video by clicking the Plus button at the top of the screen. In the box that appears, you can choose any video files that you deem fit to edit and that OpenShot supports.

Once you have imported your video, you have many options at your disposal. You can do your usual cropping, fading, and custom effects. You can also add 3D effects with Blender, making your videos come alive for the viewer.

For example, if you have recorded a video with a green screen, you can go to the Effects tab and apply a Chroma Key. You can also distort your image, echo your sound, and finally mirror it. Then, go to the Transitions tab and select one of the dozens of transition effects that can be applied when you are changing from clip to clip. These are just a few examples of what you can do with OpenShot.

OpenShot, seen in Figure 4-24, has many options for the amateur video editor and anyone interested in making their home videos look better than ever. For more help with OpenShot, check out its official support site (www.openshotusers.com/help/1.3/en/), which provides in-depth discussion of how OpenShot can get you editing videos in no time (Figure 4-25).

Play Games with Steam

package name: steam

Windows Equivalent: Steam

If you are used to playing games on your Windows or Macintosh computer, then look no further: in Ubuntu, you can use Steam to play many of the same games that were supported by Windows and OS X. Steam is available from the GNOME Software Center.

Open the Dash and search for Steam. Once Steam opens, it should look like Figure 4-26, with a box asking you to log in.

Now you can log in with your Steam credentials. If you do not have any, feel free to create some by clicking Create New Account. From here, you can follow the instructions for setting up Steam and playing games. Steam features such games as Portal and Team Fortress 2. Some games cost money, whereas others do not. Figure 4-27 shows what Steam looks like fully opened and ready to use.

Figure 4-27 Once you have logged in to STEAM, you can browse games to play, or play games you already own.

Playing to Learn with Educational Programs

Many different educational applications are available on Ubuntu. Let’s take a look at just a few of those found in the GNOME Software Center. Most of these and others can be located under the Education category in the center.

Stellarium

With a default catalog of more than 600,000 stars, Stellarium is a powerful planetarium designed to show you exactly what you would see with the naked eye, binoculars, or telescope.

In keeping with the multicultural nature of Ubuntu and the open source world, Stellarium can display not only the constellations from the Greek and Roman traditions (Figure 4-28) but also those of other “sky cultures,” as Stellarium describes them, such as the various Chinese, Ancient Egyptian, and Polynesian traditions.

Stellarium is even capable of driving a dome projector, like you would see at a large-scale, purpose-built planetarium, as well as controlling a wide variety of telescopes directly.

Marble

Marble, the desktop globe, is a virtual globe and world atlas, which can be utilized to learn more about the Earth. With the ability to pan and zoom, click on a label to open a corresponding Wikipedia article, and view the globe and maps with various projections, Marble is a welcome addition to Edubuntu’s educational packages.

Parley

Parley, the digital flash card, allows you to easily remember things utilizing the spaced repetition learning method, otherwise known as flash cards. Features include different testing types, fast and easy setup, multiple languages, the ability to share and download flash cards, and much more.

Step

Step is an interactive physics simulator that allows you not only to learn but also to feel how physics works. By placing bodies on the scene and adding some forces such as gravity or springs, you can simulate the law of physics, and Step will show you how your scene evolves.

Blinken

Blinken (Figure 4-29) takes you back, back to the 1970s, as a digital version of the famous Simon Says game. Watch the lights, listen to the sounds, and then try to complete the sequence in order. Blinken provides hours of fun with the added benefit of learning.

Other Applications Not on the Education Menu

Some educational applications are not located in the Education menu in the GNOME Software Center. Here are brief descriptions of three of them.

![]() Tux Paint: Tux Paint is a drawing package for younger children. Although geared toward a younger audience, Tux Paint still packs in some of the more advanced features of drawing packages and enables users to draw shapes, paint with different brushes, use a stamp, and add text to the image. The Magic feature offers many of the more advanced tools normally found in full-fledged photo editors, such as smudge, blur, negative, tint, and many more. There is also the facility to save as well as print.

Tux Paint: Tux Paint is a drawing package for younger children. Although geared toward a younger audience, Tux Paint still packs in some of the more advanced features of drawing packages and enables users to draw shapes, paint with different brushes, use a stamp, and add text to the image. The Magic feature offers many of the more advanced tools normally found in full-fledged photo editors, such as smudge, blur, negative, tint, and many more. There is also the facility to save as well as print.

![]() GCompris: GCompris is a set of small educational activities aimed at children between 2 and 10 years old and is translated into more than 40 languages. Some of the activities are game oriented and simultaneously educational. Among the activities, there are tasks to educate children in computer use, algebra, science, geography, reading, and more. More than 80 activities are available in the latest release.

GCompris: GCompris is a set of small educational activities aimed at children between 2 and 10 years old and is translated into more than 40 languages. Some of the activities are game oriented and simultaneously educational. Among the activities, there are tasks to educate children in computer use, algebra, science, geography, reading, and more. More than 80 activities are available in the latest release.

![]() Anagramarama: Anagramarama is a game designed to improve children’s vocabulary. Players are presented with a set of letters, which they have to put in order to create several words. Players can shuffle the letters, as well as ask for a new puzzle. There is also a time limit involved, so the challenge is even bigger. Apart from being a great pastime, Anagramarama can help users learn new words.

Anagramarama: Anagramarama is a game designed to improve children’s vocabulary. Players are presented with a set of letters, which they have to put in order to create several words. Players can shuffle the letters, as well as ask for a new puzzle. There is also a time limit involved, so the challenge is even bigger. Apart from being a great pastime, Anagramarama can help users learn new words.

Summary

In this chapter, you learned how to install and use just a few of the additional applications available for Ubuntu. Although this chapter merely scratched the surface of what each application can do, you should have enough of an understanding of each to get started with them, and the Further Resources sections should help you become an expert. Beyond the packages described in this chapter, a vast universe of programs is available. Go and explore—try out something new. At worst, you will have wasted a few hours, but you might find something that will change your life.

Always remember that a wealth of help and documentation is available online. If you ever find yourself stuck, take a look at the Ubuntu Web site at www.ubuntu.com or the Ubuntu documentation at http://help.ubuntu.com and make use of the forums, wiki, mailing lists, AskUbuntu, and IRC channels.