Chapter four

Emotional intelligence

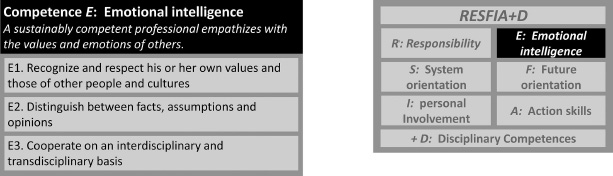

The Competence (Figure 4.1):

A sustainably competent professional empathizes with the values and emotions of others.

“I am a good listener.” This is one of the items in an EQ test you can find on the Internet. You may be familiar with the EQ, the emotional intelligence quotient, meant to complement the IQ: emotions versus intelligence. “I understand how other people feel,” is an item from another EQ test. This chapter focuses on these types of themes.

Whereas the competence of Chapter 2, responsibility, deals with the relationship between the professional and his or her tasks and is therefore task-oriented or case-focused, Chapter 3 explores the relationship between the professional and other individuals and groups and is consequently people-oriented. The ability to relate on an emotional level to others strongly depends on whether you recognize and empathize with the values and norms of that person, and whether you are able to compare them to your own.

This chapter, too, brings you three concrete achievements that you can accomplish as a professional. This time they are:

- Recognize and respect your own values and those of other people and cultures

- Distinguish between facts, assumptions, and opinions

- Cooperate beyond the limits of your own discipline

4.1 Respect values of yourself and others

Our student body is 17% Hispanic/Latino, 82% African-American, 1% Asian/Mixed Race. A large number of our students were incarcerated, experienced violence, grieved the death of a relative or friend, endured an unsafe passage into the US, and/or still live within other ills of society.

This is the beginning of a story told by Genevieve Maignan-Keogh, a school counselor who was born in Haiti and grew up in Algeria, Morocco, Libya, Italy, and the United States. She works at an inner-city high school in Washington, D.C. Genevieve continues:

“Two months into the 2013–14 school year, students and parents alike, expressed concern about one of our instructors, Mr. Bendjedid (not his real name). They accused him of being confrontational and demeaning and had a difficult time understanding his accent. A student said, ‘if you ask him a question, he’ll say: Why don’t you understand? It makes us feel like we should know as soon as he explains.’ At first I thought the students were rebelling, as do many teens. This was my first year at this school; I was unfamiliar with the teacher’s practices. I met him the first week of school and detected a strong accent as he shared great stories of his many travels, his published work, people he knew, students he helped, etc. He was definitely a confident guy. I did find him collegial. We had quite a bit in common; he was Algerian, spoke five languages, and had lived in some of the same countries I had lived in.”

“The student complaints arrived almost in concert with Mr. Bendjedid’s request to remove certain students from his English class,” Genevieve explains. “As the calls and emails came in from angry parents and students, I realized that the issue was bigger than what I had thought! I organized one meeting at a time and invited the parent(s), student, and teacher to address their concerns. I had it all planned out. I would give everyone a chance to express their point of view, process what was being said, and propose strategies that would help the student succeed.”

“There were times when I met with Mr. Bendjedid outside of parent meetings. He often looked frustrated and a couple of times said, ‘How am I supposed to teach them? This student doesn’t speak English well and can’t write. Other students barely passed English 1, are reading at the 2nd grade level, and are in my class. You’re setting me up for failure.’ Mr. Bendjedid also believed that the students were not interested in learning, did not try to improve, and did not participate. During one of our meetings, I told him that the student was a Level 3 English Language Learner and thus needed to be mainstreamed. I also reminded him that I could not retain students who passed the class. I remember feeling cornered; I felt as though Mr. Benjedid was talking at me, rather than with me. I looked down at the list of names he wanted removed from his class when he suddenly exclaimed: ‘Look at me when I’m talking to you!’ I looked around to see who he was talking to, but there was no one else; he was speaking to me!”

“I guess he thought I was being disrespectful, or I was not paying attention to him,” recalls Genevieve. “However, when I was growing up, eye contact signified disrespect, especially when adults reprimanded you or accused you of something. In American culture, it is the opposite. I have assimilated to American culture, but looking away still comes naturally for me. I’ve tried to change this, but it’s difficult.”

Although it might have been easier to condemn Mr. Benjedid, Genevieve decided to explore the triggers that created discomfort at the meetings and realized that cultural nuances played a role in their relationship. His education was more structured, one-sided, and didactic than that of present public education. She knew this from her own experience as a student in the French system. Although they had similar experiences, Genevieve recognized that she would have to respect the teacher’s cultural uniqueness and perception.

Genevieve elaborates, “Approaching student-teacher conflict is a sensitive issue. I am primarily there to advocate for the student, but I am also obligated to uphold a professional relationship with colleagues. I felt this could only be attained by allowing everyone to speak their truth, respecting the student and the teacher, by remaining impartial, and most importantly, by reminding those present that my purpose is to advocate for the student. It took me over a year to realize that our cultural similarities were in conflict. Individual perception exacerbated the conflict. I was forced to revisit my cultural norms, which were formed during my primary years, and accepted that my personal experiences clouded how I interpreted the teacher’s actions.

When I lived and attended school in North Africa, teachers were always right. Corporal punishment was a common practice. Fear of the adult meant respect. In addition, I lived in countries where men criticized, demeaned, and oppressed women. Mr. Benjedid’s approach reminded me of that fear and oppression. Subconsciously, I was resisting colluding with his notion that children’s opinions and feelings did not matter. I did not want to engage in ridiculing children’s rights. I was also rejecting what I interpreted to be gender-bias and prejudicial attacks.”

It was difficult for Genevieve to keep her feelings in check, but she managed by being as objective as possible. “Every time I felt attacked, my instinct was to go into survival mode. I needed to defend the students, and myself. With each instance, I fought my primordial need to save face, and removed the feelings from the situation. I guess this relationship was the tipping point, which forced me to take a step back. I had to ask myself, ‘What is the perceived threat?’ and ‘Where is this feeling coming from?’ These two questions help me navigate through other conflicts, which also derive from cultural differences.”

And how did this particular conflict with Mr. Benjedid get solved you may wonder? According to Genevieve, the complaints from students, parents, and the teacher continued, and neither party was able to rise above its subjective perspective. She concludes, “The principal eventually merged two social studies classes, in order to free up a teacher, and created a new section of English 2. Mr. Benjedid gave me a list of students he wanted removed, and I enrolled them in the new English 2 section.”

Looking back, Genevieve feels that this challenging experience strengthened her abilities to navigate through cultural intricacies. “Respect, introspection, and the will to change – those are three important skills necessary to go beyond misleading interpretations and move toward solutions. I always start with respect because that is what keeps us civilized. For me, respect means understanding that all lives have a purpose and matter. It means recognizing that there are differences, and not necessarily understanding why those differences exist. Introspection is next because that is where change begins. The will to change follows because it takes courage. Ultimately, the only one you can change is yourself.”

The achievement

You recognize and respect values, both your own and those of other people and cultures.

This means:

- You formulate the values from which you think and act as a professional.

- You do the same for or with others who are involved or have an interest in your professional actions.

- In order to do that, you “listen actively” to others, and you communicate with them respectfully about the differences in values. Whatever you say or write about them, you check with them.

- When you cooperate with others, you utilize both the similarities and differences of values as an enrichment and reinforcement of the quality of your activities.

Actively listening is much more than just hearing what the other says. It is trying to understand what is being said, and what is not being said but intended. It means ask further if you don’t understand the things the other person is trying to say, and it means that you check whether you have understood the other person correctly, for instance, by repeating or summarizing the message in your own words.

Actively listening also implies that you let the other person realize that you are listening and that you are interested in what they have to say. You signal this not only with words (verbally) but also through your posture and gestures (non-verbally).

Concerning values, relevant concepts include cultural values, ethical norms, beliefs, religion, philosophy of life, and traditions. The above story about Genevieve Maignan-Keogh’s work deals with personal values, cultural sensitivity, and mutual respect.

Reader, I have a confession to make. In the first years after I started working for sustainable development in 1991, I rarely thought about these human aspects of sustainability. In those days, I primarily discussed the importance of science and technology. I thought if we were able to close the cycles of products and materials (what we now call C2C, “Cradle to Cradle”), calculate the environmental impact of our products and processes with the aid of life cycle assessment (see Chapter 2) to minimize the impact, and use sustainable sources of energy, then the world would become sustainable. Perhaps you will forgive my naïveté when I tell you that I graduated in theoretical physics and that in those years, I was the manager of a brand-new education program called “sustainable technology,” which was partly designed by me. No wonder I was biased. My personal management education had only just begun, let alone my Ph.D. program in social sciences, which I completed between 2006 and 2010.

In the 25 years between then and now, my view on sustainable development has shifted fundamentally. The fact that I am at present – following famous scientists and authors – writing about a balance between people, planet, and profit is a consequence of a personal transition over the course of the first ten of those 25 years: from mainly planet to the entire Triple P.

It’s funny. My co-author, Prof. Rachelson, tells me that for her dissertation she researched the attitudes, beliefs, and practices of community college professors regarding sustainable development. She interviewed professors about their personal journeys toward sustainability, their definitions and interpretations of what sustainability entails, and their ideas for infusing sustainability into the higher education curriculum.

If I think about which topic currently touches me most deeply, it is certainly people. Sure, planet issues are incredibly important. If we don’t find ways to solve the climate crisis or fail to sufficiently protect the tropical forest and biodiversity, we are heading toward global catastrophes. The profit themes are also of crucial importance because as long as we don’t succeed in designing a system in which the world economy becomes more stable and in which sustainable energy, food, and industrial products become more financially attractive, the world will never be sufficiently sustainable. All this is true. But when I see how people like Genevieve advocate for their disadvantaged students, I am deeply touched. It also moves me when I read how homosexuals are granted the legal right to marry, women and minorities the right to vote and to acquire leadership positions in business and society, children the right to safety, health, and education, religious and non-religious people the right to freedom of speech, and the elderly the right to a dignified and self-decided end of life. This is all about human dignity, to which everybody is entitled, about respect, and finally about everyone’s right to be considered as a person, to exercise self-expression, and to participate actively in society. These are the highest goals of sustainable development in my view: emancipation, empowerment, participation, cultural diversity, and personal and social identity. It short, it is about the right to be who you are.

These kinds of topics concern each and every professional. Environmental, technological, or economic sustainability may primarily be topics for specialists. In Chapter 11, which deals with different kinds of specialists, you will find some nice examples of them, but every professional in each and every discipline can strengthen human sustainability. The next story sets another great example.

4.2 Facts, assumptions, and opinions

Phew! I get really tired when Sandra Veenstra tells me about her clients. Sandra is a psychotherapist who treats all kinds of problems her patients complain about, often a combination of medical and psychological issues. One of these patients was Mrs. H., whom Sandra had diagnosed as chronically fatigued. According to the patient, Mrs. H. herself was not blame. She was sure about that, she told Sandra.

However, when the psychotherapist inquired what Mrs. H. did on an average day, the patient produced a long list. In the morning, she took her children to school and picked them up afterwards. She did the family’s grocery shopping, cared for the disabled aunt, cleaned the windows (inside and outside), vacuumed the house daily, ironed clothes, dusted the furniture, changed the bed sheets at least once a week, and much, much more. Quite a lot of work for a chronically fatigued patient!

The situation was rather serious. Mrs. H. had quit her part-time job. Not only did she suffer but so did her husband, son, and daughter. Mrs. H. was often depressed, yelled at her children, and lashed out at her husband, who could not take it anymore. The family was about to fall apart.

A typical case for cognitive behavioral therapy, the psychologist decided. This type of therapy implies that you start investigating whether the patient’s ideas, her cognitions, are based upon facts or not, and what the implications for her behavior are.

- “Why do you clean your windows every week?” Sandra inquired.

- “Well, that’s what should be done, right? I’ve learned it that way!” the patient replied, visibly proud.

- “Aha,” said Sandra. “The same is true for vacuuming the house every day, I suppose?”

- “Certainly. This is what a good homemaker should do,” Mrs. H. answered.

Ah, a typical example of a “should-ism.” Another one quickly followed:

- “And what about your aunt, do you really have to take care of her?” Sandra asked.

- “Of course, I should,” was the answer. “My aunt is seriously ill. She can’t do that herself!”

Sandra continued with the interview, trying to discover together with her patient if all those “certainties” were really that certain. What would happen if she cleaned the windows less frequently? Would the house collapse? Would people start to think badly about her? Step by step, Sandra challenged her patient’s cognitions. All should-isms were exposed, one by one. Were they really facts or opinions?

- “Suppose you would vacuum the house less than once a day,” Sandra asked Mrs. H. “What exactly could go wrong?”

- “Well, I … I’m not sure, but … I would certainly feel uncomfortable!”

It took a while before Mrs. H. acknowledged that the necessity of vacuuming every day was an opinion and not a proven fact. On the other hand, it became clear that her aunt was seriously disabled and did need help. No doubt about that.

- “But, is it really you who has to offer all the help? Aren’t there any other family members who can contribute?” Sandra wanted to know.

- “Ha, they will never do that, I’m sure!” Mrs. H. asserted.

- “Are you sure?” asked Sandra.

- “Oh yeah, meet my family!” Mrs. H. replied.

- Was this a fact, as Mrs. H. stated, or was it an assumption?

- Sandra asked, “Have you ever asked them?”

- “No. No reason. I just know what they are going to say,” was Mrs. H’s response.

- Right, it was an assumption. Following Sandra’s advice, Mrs. H. started to reevaluate, and within a month, the family came to an agreement about taking turns caring for the disabled aunt.

Over the course of a series of therapy sessions, the patient discovered that there are many tasks that are not really necessary and that it is one’s own choice how frequently one does laundry, dusts, or cleans. Mrs. H. decided to change the bed sheets once a month and to vacuum the living room once a week. As she spent the time she gained on relaxing and recovering, her constant strain ended, and she found a healthy balance. Her condition improved, and after a few months, she concluded that “actually, she was not chronically fatigued” anymore. Her mood improved, her energy increased, and she finally found the time to dedicate her attention to her family and hobbies. Mrs. H’s entire family recuperated considerably, and her marriage was saved.

The achievement

You distinguish between facts, assumptions, and opinions.

This means:

- When it comes to assertions (both your own and those of others), you

- determine whether they are facts, assumptions, or opinions.

- You communicate your conclusions in such a way that others, including the person who made the assertion, come to a consensus.

- During your professional activities, you decide when a fact, an assumption, or an opinion is needed, and you plan accordingly.

- Whenever necessary, you design acceptable and realistic methods to turn an opinion or an assumption into a fact, or to replace a fact with an assumption and/or an opinion.

Facts, assumptions, and opinions – these often get mixed up. Moreover, and perhaps equally catastrophic, not everyone is always aware when hard facts are required and when insisting on them may be less wise. Let me give you an example.

Every now and then, the following happens: a village or town gets agitated over a certain local hazard – let’s say, over radiation coming from a recently installed cellphone tower. People have noticed, let me assume, that a significant number of leukemia cases have been diagnosed in the nearby area. They are absolutely sure that this is due to the cellphone tower. “That damn cellphone tower has to go!” people demand. Fair or unfair?

Policymakers and politicians know that this issue is a hornet’s nest because all kinds of assertions intersect: facts, assumptions, and opinions. For instance: “A significant number of leukemia cases have been diagnosed.” This assertion may be a fact. If so, it is an outcome of thorough scientific research, in which the number of leukemia cases has been exactly determined and compared to a control group, corrected for variables such as age structure, educational level, socio-economic status, ethnic background, presence of highways and industrial areas, and at least 20 other factors that might influence the statistics.

Next, the researchers have determined that – yes, indeed – the percentage of leukemia patients is to a statistically significant extent higher than might be expected. After a scrupulous review by “peers,” i.e. by other scientific researchers who are relevant experts, they publish the results in an international medical journal. In short, this hypothesis is evidence-based. By the way, even then it may happen that additional scientific research establishes that the so-called “fact” appears doubtful. However, it is just as likely that the “significantly higher number of leukemia patients” is only an assumption that resulted from the fact that, by coincidence, two children suffering from leukemia live in the same street, which got the rumor mill working.

The next remark – “That damn cellphone tower has to go!” – most certainly is an opinion and not a fact. What can you do in such a situation if you are the one who is professionally responsible for it? Set up genuine scientific research? Perhaps, if you have the opinion that the outcome will help – and that it will be published in time. However, real life has shown that scientific facts rarely help in a situation like this. Mostly opinions and emotions count, and usually they don’t change when facts contradicting the general opinions are offered.

The example above illustrates how important it is to decide what is needed – in every context – facts, assumptions, or opinions. It also illustrates the possibility of flexibly changing from one to the other, for instance, by turning an assumption into a fact based on solid investigation. The example also demonstrates the limits of such a change in real-life situations.

Taking the (more or less) reverse approach can also yield results. Instead of striving for objectivity, you can start a quest for intersubjectivity, i.e. for generally shared and supported assumptions or opinions. You may find that scientific proof, showing that the cellphone tower cannot possibly cause leukemia, causes anger and aggression. If so, it will probably be wiser not to rely on this evidence. Instead, you might focus on the emotions to find out if the community can come to a consensus about what should happen: remove the cell tower even if no scientific evidence supports it, or not?

4.3 Cooperation

There is an ascending series of words: monodisciplinary – multidisciplinary – interdisciplinary – transdisciplinary. I immediately want to add that not everyone uses these four words in the same way. I will just tell you how I use them, in accordance with how (as far as I have observed it) they are most generally used.

If a teacher of physics – as I myself have been for quite a few years – designs a lesson just on his own, focusing solely on the physics content of the lesson, he is working in a monodisciplinary style, completely within the boundaries of his own discipline. If he prepares a thematic week about nature and the environment – still on his own – he is working multidisciplinarily at that moment: in his head, he combines elements from a variety of disciplines.

Maybe such preparation will result in a magnificent thematic week, but it is to be expected that this week will become much more wonderful and enriched when the teacher of physics cooperates with colleagues from different disciplines, and maybe even with the school psychologist, the career counselor, the janitor, and a bunch of external experts. This cooperation of a variety of experts is called interdisciplinary, literally: “between the disciplines.”

But it can be even better. Many aspects of nature and the environment can be discussed, and not just by experts. You may include “ordinary” people: inhabitants of the region, representatives of action groups, walkers, and cyclists. They are all persons who feel connected to the topic of the thematic week, not because they are experts in a relevant discipline but for other reasons. When you also actively involve these stakeholders in the preparation of the thematic week, you make them members of a transdisciplinary team, literally a team “beyond the disciplines.”

In short:

| Monodisciplinary | = | one or more experts, one discipline |

| Multidisciplinary | = | one expert, several disciplines |

| Interdisciplinary | = | several experts in cooperation, each from his/her own discipline |

| Transdisciplinary | = | interdisciplinary + stakeholders without some special expertise |

The crowdsourcing project involving Simone Lopulisa and her bank that Chapter 2 starts with is a nice example of a transdisciplinary approach. Not only were the bank experts actively involved in the stakeholder analysis, all kinds of people and societal organizations were also invited to join in, and it proved to be successful.

Here is another successful story – about “Transition Towns.”

The American Wikipedia entry describes a transition town as:

A grassroots community project that seeks to build resilience in response to peak oil, climate destruction, and economic stability by creating local groups that uphold the values of the transition network.

The Dutch Wikipedia adds to this:

Transition Town: a local community (city, quarter or village) that takes the initiative to make its way of living, working and housing more sustainable.

The Transition Town (TT) movement started in the village of Totnes in England in 2006. From there, the idea quickly spread to 50 countries around the world. According to Transition United States, the nonprofit umbrella organization that supports networking between transition initiatives in the United States, there are currently 163 Transition Towns in 37 states (October 2017). A person who can explain how cooperation in a Transition Town works is Kirk Ritchey, a Transition Town core member and organizer from TT Woodstock, New York.

Woodstock rings a bell? Some of you may have heard the name in a very different context – the 1969 music festival that influenced generations featuring Jimi Hendrix, Joe Cocker, Janis Joplin, Santana, etc. – but these days, the town is making an impact in other ways. In 2012, the community joined a growing number of towns and municipalities worldwide and officially became a Transition Town with the goal of “building local resilience through community action.”

A TT initiative is set up by a horizontal network organization and local thematic working groups around themes such as sustainable energy, urban agriculture, local economy, biodiversity, education, and transportation. Volunteers from a variety of professional backgrounds do most of the work in a TT GROUP.

Kirk Ritchey was initially drawn to TT Woodstock because he loves cycling and felt that the town needed safer streets and more bike lanes. His working group – Transportation – advocates for “safe passages and lanes for pedestrians & bicyclists” and also seeks to “increase awareness of safety for pedestrians & bicyclists and the value of vehicle slow zones throughout Woodstock.”

In order to act collectively, TT organizers like Ritchey must know how to work with people across different disciplines in a cooperative way. “Transportation,” Ritchey says, “is a perfect example. The goal is to establish an incremental improvement plan, so you need to interface with the local government, residents, and other volunteer organizations. To qualify for grants, organizations need to get their projects into the county’s official comprehensive plan,” explains Ritchey, and to this end, he and other like-minded residents from different Woodstock-based volunteer organizations have formed the Active Transportation Advisory Council “to generate a plan that coordinates with local, county, and state transportation agencies and is adopted by Woodstock’s town leaders.”

According to Ritchey, “cooperation thrives when you allow people to follow their individual passion, so we started to identify where people’s passions lie.” In Woodstock, these interdisciplinary passions include garden sharing, wellness, transportation, green energy, and organic waste. “You can’t create that,” Ritchey emphasizes.

Transition Towns provide people from different backgrounds with opportunities to come together and cooperate. “People seek community; they want to be part of something,” Ritchey explains. When people share values, they are more likely to cooperate; however, cooperation is not always easy. “Breakdowns occur. Some people join because of a single interest, for instance, anti-fracking, and this can derail groups from making progress. There are also people who join organizations because they are against something. When this happens, you have to go back to the principles and say: Our source of cooperation is based on being for something rather than against something. Let’s stay in touch with what we are for and what we share. Adhering to the ‘7 Guiding Principles of Transition’ posted on the group’s website is a good starting point.”

Ritchey thinks, “Individuals joining the Transition Town movement also have to undergo ‘an inner transition.’ This includes developing interpersonal skills for group settings.” Because people often have difficulty with communication, TT Woodstock created a team called “Working Group Support” to specifically address conflict resolution and help members interact more positively with one another. The group focuses on “strengthening people’s relationships, so we were able to avoid dysfunction” Ritchey adds. Wherever they are, Transition Towns are young organizations that rely on forming alliances with other groups. To cooperate, Ritchey says, you “have to work on key relationships, for example, with the fire department, the city council, etc.”

Only recently, the town had to mobilize when a water company “set up shop to utilize the town’s water,” Ritchey remembers. “A lot was at stake. People said, ‘Wait a minute. We don’t want this going on.’ There were a lot of people against the privatization of our local natural resource (water). TT Woodstock provided a forum where people from the community could come together to discuss this issue. We created a platform to look at our watershed from a systemic viewpoint, which we called ‘Our watershed is our lifeboat.’ Collectively, our town began to understand that it’s our responsibility to manage this local resource so it’s available to everyone, not just those who will purchase it.” The town’s efforts worked. The water company eventually withdrew its bid and left Woodstock.

In the meantime, Ritchey’s working group – Transportation – continues to generate ideas for better bike lanes, signage, and pedestrian pathways in a cooperative way. They have one year to present their plan to the town’s local government and make a positive impact for future generations.

The achievement

You act in a multi-, inter-, or even transdisciplinary way.

This means:

- You act in a multidisciplinary way – In your professional activities you involve aspects of disciplines other than your own.

- You act in an interdisciplinary way – You carry out your professional activities as a member of an interdisciplinary team in which you cooperate intensively with professionals from a variety of other disciplines.

- You act in a transdisciplinary way – You also actively involve others, who don’t represent a specific professional discipline but who have a stake in what you do for other reasons, in your professional activities. This may involve experiential experts but also amateurs or laymen who for whatever reason are or feel included. It may concern individuals but also representatives of groups.

Transition Towns and transition initiatives – if perhaps you are not fully familiar with the concept of transition, you may appreciate it if I tell you that it is a “fundamental change of a system based upon a paradigm shift.” A paradigm is a concept that – in just one word – describes a whole way of thinking, and a paradigm shift is a fundamental change in the way people think and talk about things. During a transition, not just a physical system changes, but also the underlying notions, values, and ethical norms. An example from the ancient past is the transition from a hunter and gatherer society to one based on agriculture, accompanied by the transition from a nomadic to a sedentary community. More recent transitions are the industrial revolution, the rise of democracy and human rights, the foundation and growth of the United Nations and the European Union, and the introduction of the present IT-based society starting with the telegraph, continuing with the telephone, radio and TV, and presently arriving at computers, automation, the Internet, and smart phones, smart grids, smart houses, and smart cars.

Many global systems have been arranged in a highly unsustainable way. This is true, for example, for the international system of agriculture and food as well as for the energy sector, which is almost completely based on fossil fuels. Not only are we approaching peak oil, but aside from that, oil, gas, and coal are destroying our climate.

Before going to Chapter 6, in which I will tell you more about systems and the next sustainability competence, systems thinking, I first want to share a little more about professionals who are not just competent as such, but who are sustainably competent. We need a great many of them.