Chapter two

Responsibility

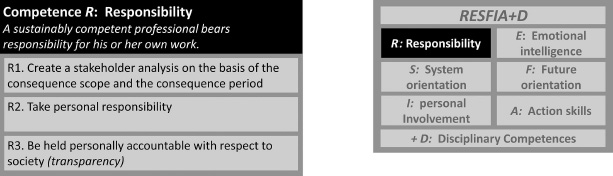

The Competence (Figure 2.1):

A sustainably competent professional takes responsibility for his or her own work.

“I take full responsibility.” You can read this in the newspaper or hear it on TV. Usually, it means: “I quit my job.” You may be watching a politician or a football coach who is resigning.

People who say such a thing have a very limited view of responsibility. To express it even more strongly, it is actually a euphemism for transferring the responsibility to someone else.

In reality, responsibility, of course, is something totally different. Let’s say you have the responsibility for a group of elderly patients, or children. Responsibility then means that you do not leave, but instead take care of them continuously and, if necessary, defend their interests against those of others. Of course, if you cannot do that anymore, you act responsibly if you transfer your responsibility to someone else.

To take responsibility means standing for what you do and communicating that openly. As a professional, you do that in the first place by investigating conscientiously what kind of consequences your work has, and for whom – in a positive or negative sense. To put it more formally: by discovering all stakeholders in your work.

Each of the six general sustainability competences is linked to certain concrete achievements. By realizing such achievements, a professional demonstrates that he or she possesses the related competence. For the competence Responsibility the achievements are:

- Find stakeholders

- Take responsibility

- Be accountable

2.1 Find stakeholders

Simone Lopulisa’s ideas immediately fell on fertile ground. Simone works for a bank, one of those special banks that have adopted sustainability as their basis or their mission, and really operate accordingly. The bank attaches value to transparency and to dialogues (or relationships) with customers, stakeholders, and society. Probably that was the reason why Lopulisa’s plan was immediately embraced. She proposed to perform a stakeholder analysis in a special way.

Who has an interest in what you do as a professional? Your customers, of course, or your students, or perhaps your patients? Maybe your shareholders, managers, colleagues, or employees? Please choose whoever applies to you. Your partner and your children, if you have any. All are obvious stakeholders of your work.

But there is more. Suppose that your work produces annoying noises, or perhaps your visiting customers cause parking problems. In those cases, you create a nuisance for your neighbors. This implies that they, too, have a stake in your work, albeit a negative stake.

Negative stakes may exist in many ways. If you work too hard, your family may suffer from it. If you sell clothing that is produced in China or Bangladesh, there is a chance that you profit from child labor or wage slavery. If you drive to work, you cause emissions and greenhouse gases – even if you use an electric car – and aerosols. Don’t get me wrong. This is not an accusation. Everybody causes negative effects. You just can’t avoid it. Of course, you can strive to minimize them.

The first step in accepting responsibility consists of finding all stakeholders, those with a positive stake – a benefit – and those with a negative one. The next step entails consulting with them, aiming to maximize the positive and minimize or compensate for the negative.

If a company performs a stakeholder analysis, it usually starts with a group of sensitive and experienced staff members discussing who has a stake in what the company is doing. In most cases, the traditional groups will be recognized, e.g. the shareholders and the customers. However, the risk is that there will be “blind spots,” causing certain kinds of interests to go unnoticed. Simone Lopulisa proposed to adopt a totally different approach, through which each and all – known and yet unknown – stakeholders would get the opportunity to present themselves. Her strategy was based on crowdsourcing.

“This goes far beyond defining the target group,” Simone explains. “Crowdsourcing is the online gathering of knowledge and suggestions of a large group of people aiming at creating ideas, solving problems or the creation of a policy. Crowdsourcing makes you – as an organization – look further than just the traditional group of stakeholders. Social media enables you to reach a much larger group of partly yet unknown people and to spread the message fast. The dialogue you start this way is different from what it would have been if you had only communicated with your clients. This ‘new group of stakeholders’ often delivers refreshing and surprising ideas.”

In the summer of 2011, the method was applied for the first time, with the theme “human rights policy.” This theme was divided into four parts: fair trade; against child labor; against arms trade; and sustainable energy. Simone placed challenging assertions on a blog, sparking an online discussion. Everyone who wished to participate in redefining the bank’s policy was able to join. The bank asked for assistance from social organizations, e.g. Amnesty International, labor unions, Foster Parents Plan, and Cordaid to introduce the process to a lot of people and to invite them to join the discussions. The bank employees were asked to utilize their private networks in order to further enlarge the publicity for this new policy. All in all, this crowdsourcing proved to be highly successful. At the height of the action, 140,000 Twitter users and the bank’s own sustainability platform, with 52,000 members, were involved.

The bank used the contributions to the discussion to improve its policy. One of the results was that privacy and freedom of expression became a separate chapter in the human rights policy.

One year later, Lopulisa gave me some advice for those who want to try to do what she has done. “Always respond. Don’t make any promises: If you promise to respond to every message, then do so. Be honest, every time you respond. Thank the involved persons in a personal way. Send them feedback about what you have done with their input. Get going with the input you receive, and always inform the involved people if this appears to be impossible, for whatever reason. Crowdsourcing is a tool, not a target in itself: always start from intrinsic motivation. Feel free to invite those who are eager to be involved more than once. Attempt to deepen the online dialogue by continuing it offline.”

The achievement

You create a stakeholder analysis based on the consequence scope and the consequence period.

This means:

- You find everyone who is a stakeholder in your work. For each one, you determine what the stake consists of: both the positive and the negative aspects.

- For this purpose, you start by determining the consequence scope and the consequence period of all your professional activities.

- You consult all stakeholders or their representatives in order to determine their stakes.

- You use the conclusions of this analysis and the consultations for the continuous improvement of your work.

Many of our (positive or negative) stakeholders are perfectly able to defend their own interests, but not all. Little children and those with mental disabilities don’t have the ability, or only to a lesser degree. In that case, you don’t communicate directly with them but with their representatives: parents, interest groups, the government, or maybe a legal counselor. Can animals be stakeholders? Legally, they can’t, as they are not persons according to laws in many countries; however, it is clear that some decisions will have a favorable or an unfavorable impact on certain animals. So yes, animals can be de facto stakeholders, and there are organizations defending their interests. How about nature as a whole? “Sure!” is the answer of organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). In other words, a valid stakeholder analysis, one that is comprehensive from a sustainability perspective, can be quite sizeable.

A valuable concept is the consequence scope. This is the full extent of persons, organizations, communities, and the environment that experience the consequences of your decisions and activities. Yet, even that is not sufficient.

Sustainable development specifically is not only related to the present but also to the future. Is it possible for people born in or after the year 2050 to be stakeholders of the work we do now? Absolutely, beyond any doubt. Taking the interest of these yet to be named individuals into account is definitely a main aspect of our responsibility. However, it is impossible to communicate with them here and now. This means that we should act as their representatives and think about their interests.

The counterpart of the consequence scope is the consequence period. That is the time it will take before the consequences of your decisions and actions have fully faded away. Consequence periods can vary. If I choose between a cup of coffee and a cappuccino, the consequence period of my decision may be a quarter of an hour, as afterwards the coffee is gone and forgotten. If the national government decides to construct a transcontinental railroad or a project like the proposed Keystone XL pipeline that would run from Alberta (Canada) to Texas, the consequence period of that decision is at least a full century. The consequence period of a nuclear plant amounts to hundreds of thousands of years, due to the radioactive waste. Consequence scope and consequence period together form two dimensions: the dimensions of “space” and “time.” Together they are helpful to define a natural rule of thumb for making sound decisions.

Directions for a good decision

A decision can only be a good decision:

- if the advantages and disadvantages for the entire consequence scope are determined and scrupulously weighed in consultation with the stakeholders; and

- if it can be reasonably expected that the people at the conclusion of the consequence period will think it was a good decision.

2.2 Take responsibility

Redmond, a leafy suburb of Seattle, Washington, already had two mosques. When Hyder Ali first proposed building a third one, the local Muslim community initially did not understand why another mosque was needed in East Seattle. The two existing ones were predominantly religious places of worship, explains Ali, the mosque’s founding president and current board of trustees member. “We, however, wanted a new organization that addressed spiritual, social, cultural needs of the community, which we commonly referred to as ‘a place to pray and play.’ It was the year 2006, and this was a new idea. We had a vision of inclusiveness, which meant offering positions on the board for both men and women and giving women a choice whether they wanted to worship behind a partition or not. Back then, such an arrangement was not so common.”

The new mosque was going to house conference rooms, meeting places, a banquet hall, a café, a gym, and an indoor basketball court, so the facility had to be spacious. It sounded like a great plan, but the community was fragmented. “People didn’t understand our vision. They would ask: Why do you want to build it and why so close to an existing mosque?” Ali recalls. “They say it is location, location, and location. The place had to be where people lived.” Ali knew that his responsibility as a community leader was to be proactive to avoid further conflict. His non-profit organization, Muslim Association of Puget Sound (MAPS) started renting space in an office building, and Ali set out to convince community members. “There was a huge potential in the community that was not being tapped into. A portion of the community felt disenfranchised … We needed an institution that gave this segment ‘a platform to pursue their dreams.’ ”

Ali encountered several challenges. “The community had grown large enough that the city asked us to either find a different location or ask the landlord of the rental facility to make extensive changes to meet city codes … After some search, we were lucky to find an ideal place in a perfect location but had two problems. First, we needed to raise an enormous amount of money, which had not been done before. We also did not know if we would be able to sustain such a facility operationally. The second challenge was how to rally the community behind this project. Changing people’s social habits is hard. People go where their friends go.”

Three years passed. It was 2009, and while MAPS was busy planning the construction of its new mosque and community center, another mosque project on the other side of the country started drawing nationwide attention. Since the 9/11 attacks, public sentiments toward Muslims had changed and the proposed mosque, known as Park51, adjacent to Ground Zero, resulted in considerable conflict as many people were opposed to a mosque so close to the historic site. The incident certainly did not help Ali’s cause.

Ali had to weigh his responsibility. Under the existing circumstances, it would have been easier to drop the plans, but when considering the future, he strongly felt that the community in Redmond had a right to a modern, inclusive community center that would meet the needs of all stakeholders. He had been appointed president of the organization, so he felt his duty was to push the plans through and provide his community with the center it deserved.

Looking back, Ali remembers: “You have to be 100% sure that you are doing the right thing. You have to have a vision. We talked to the different stakeholders in the city. Part of our mosque’s charter was to be visible and open. We invited the mayors of all the nearby cities. That was in 2010, when the New York controversy was at full blast, and we were a bit impacted. The mayor of Redmond was in favor of having a diverse community, but there was a neighbor who came to the city meeting with a concern about parking and his business. Later, when we addressed his concerns, he withdrew his objection, and we’ve had a good relationship ever since.”

Asked how he and his fellow leadership members addressed the challenges responsibly, Ali responds, “First, through constant communication to the community both in our personal capacity and in formal settings. Also, through building credibility by delivering on what we promised. For example, we said, we would have an elected board, and we held our elections as promised. Finally, through community engagement. For all major decisions, we solicited community feedback and relentlessly articulated the rationale for our decisions. It’s important to listen and reflect. You have to balance between listening, and leading with your conviction … We also always took the high ground when we felt we were misunderstood or were not treated as we had expected. We did not want others to define who we were, and so did not give up on our vision to appease others.”

The new mosque opened in 2011. Aside from serving as a place of worship, it has blossomed into a community center for the people of Redmond, offering robotics and art classes for children, SAT tutoring for high school students, ESL courses for local residents, and opportunities for interfaith activities.

The achievement

You accept personal responsibility and act accordingly.

This means:

- You feel and show personal responsibility for your professional activities and their consequences.

- If different professional responsibilities conflict, you weigh them carefully against each other and act accordingly.

- You apply this responsibility proactively, by involving current and possible future developments and trends.

- Based on your personal responsibility, you strive continuously to improve your activities, thus contributing to sustainable development.

- You have to listen, but sometimes you have to lead based on your conviction.

It may not seem very hard – taking responsibility for your work, and it isn’t, as long as your decisions and actions match one another and with what you think is right and enjoyable. However, what if they are not? What if you are forced to make tough decisions when the interests of different stakeholders conflict? It is then that you have to judge critically where your primary responsibility lies and stand for what you do so that those who depend on you know they can rely on you.

Sometimes the distinction between the words “responsibility” and “accountability” are not clear to everyone. However, they are not equal. Responsibility is something that you accept and then carry. It is something that happens inside of you: a decision you make, and after which you act accordingly.

Accountable is what you are to others. Whereas taking responsibility happens inside you, accountability takes place between you and the outside world, and not just in one direction but also in the form of a dialogue. Show what you do: be transparent! That is what the next competence is about.

2.3 Be accountable: transparency

Herman Betten is the manager of communications at DSM, a large multinational company. DSM is highly active in the field of sustainability and corporate social responsibility (CSR), and Betten is one of the driving forces behind it. “Although I consider myself a financial nerd – I design Excel sheets for pleasure – I am convinced that companies should do more than just make money. They need to exercise social responsibility as well,” he wrote on the website About.me.

Hermann is a dedicated person. On behalf of DSM, he took part in a roundtable organized by the British newspaper The Guardian together with the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, an international non-government organization (NGO). The theme of the meeting was the fourth Millennium Development Goal: reducing global child mortality by two thirds in 2015. The attendees discussed options for public–private cooperation, in which governments and NGOs join forces with companies to combat malnutrition. Betten strongly believes in such combined efforts, including an intensive commitment of DSM. “We take ‘people, planet and profit’ seriously. We believe that we are capable of helping others solve the world’s biggest problems.”

Betten has been involved in the annual reports of his company for several years as manager of communications. In recent years, big steps have been taken toward transparency, and this is highly appreciated. “DSM’s annual report is very readable, according to the jury, and it is an integral report in which CSR is discussed as the very first item. There is improved information about the dialogue with stakeholders, compared to last year (…). The jury is highly impressed by the attention given to the issues in the chapter ‘What still went wrong.’ ”

These are a few of the opening lines in the jury report of the Crystal Awards 2012. In that year, DSM was – just as the year before – the winner of the Crystal, subtitled the ‘award for discerning societal reporting.’ “Of the three finalists,” the jury report continues, “DSM’s report has the strongest external orientation. The main themes in the report and their progress have all been placed in a societal context. With the initiative of a Sustainability Advisory Board DSM shows that it sets another step on the path of CSR, and the company also shows which roles each member of the Board fulfills in the societal context. With this ‘Walk the Talk’ the board sets the example for the rest of the organization.”

An annual report of a multinational company such as DSM (in 2012: net turnover 9 billion euros; 23,500 employees on five continents) is not easily prepared. Many people contribute to it, but there has to be one person responsible for the overall design. Betten wrote to me about how the award-winning reporting was developed.

“From 2007 until 2011, I was allowed to design and edit DSM’s annual reports. What for me started as a financial report – with a Triple P report added to it, prepared by someone else writing about the relations between people, planet, and profit – ended as a fully integrated annual report which served all stakeholders. In the last decade, the influence of businesses on many aspects of the global society has grown considerably. This increased influence brings forth a stronger responsibility and hence the necessity of being accountable to stakeholders.”

Betten tells me about the mind shift that is taking place in many companies, from shareholder value to stakeholder value, as it is the case with DSM:

Not long ago, this accountability (and reporting) was primarily aiming at the shareholder, and listed companies were often the only ones with a (financial) annual report. But a company, whether listed or not, has many more stakeholders than just the ones holding shares. Employees, local residents, customers, suppliers, the government, and societal organizations – they too have an interest in the affairs of an enterprise. When DSM’s Board decided in 2010 that we would integrate the financial report and the Triple P report, I became very enthusiastic. Of course, in practice it was not always easy, but thanks to the hard work of a large group of colleagues, we were able to join the non-financial issues with the financial ones and to publish one combined report at the start of 2011.

This integrated report was partly based on the directives of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), an international standard for transparent reporting. In order to show you some aspects of this transparency at DSM, I selected a few quotes from the annual report. I don’t use the two award-winning editions of 2011 and 2012, but the third integrated report of 2013, which has been further improved.

“As part of its 2010–2015 strategy, DSM in motion: driving focused growth, the company has taken sustainability to the next level. In addition to fulfilling its own responsibilities toward society, DSM has successfully developed sustainability as a strategic driver of growth. (…)”

As part of the strengthening of the regional associations, DSM established a regional China Sustainability Committee in 2012, which helps to create more awareness of sustainability as a business driver at DSM China. DSM initiated the China Triple P Supplier Engagement and Development project in July 2013, in partnership with Solidaridad and Manpower. The aim is to use the people, planet, and profit angle to engage suppliers to create a more sustainable supply chain.

DSM India has defined a sustainability roadmap with specific focus areas, and these are being driven by an India Sustainability platform comprised of the different business groups led by the DSM India president.

In August, Feed & Food magazine (Brazil) awarded DSM a Troféu Curuca de Sustentabilidade, the Brazilian ‘sustainability Oscar for agribusiness.’ The award was given in recognition of the technologies and solutions DSM has developed in the fight against hunger around the globe, as published in the article “Vitamins for Human Development” in the 68th edition of the magazine.”

There are many more remarkable texts in the annual report of 2013 that I would love to show you – for example, the one about the People LCA tool. It is the people equivalent of the planet-oriented LCA method – the lifecycle assessment – that allows you to calculate the environmental impact a product has, and which many companies have applied for years. Then there is the part about research toward developing a system of social standards for sustainable and innovative procurement in Europe and Asia, in which the occurring social issues are considered realistically through the eyes of stakeholders. Another text deals with the Global Suppliers Sustainability Program, through which DSM actively encourages its supplier to operate and produce sustainably. But I will hold back and not go on about sustainability at DSM; after all, you can download their annual reports yourself and study them. (For the web link, see the last pages of the book.)

The reports don’t just mention the positive stories. As the jury of the Crystal Award explains appreciatively, the report is open and honest about ‘what still went wrong.’ Two such incidents happened in 2012: “At DSM Sinochem Pharmaceuticals in Yushu (China), a dust explosion occurred in the packing area of the site. Fortunately, there were no injuries, but this incident has been classified as a serious near miss. At DSM Ahead in the Netherlands, an employee had his work restricted because his skin became irritated by the substances he had been working with.”

Regarding the company strategy and transparency, DSM is involved in a continuing dialogue with all kinds of stakeholders. Besides shareholders, customers, and employees, the report also mentions suppliers, local communities, end users, comparable companies, financial institutions, governments, investors, NGOs, and interest groups.

Still, in spite of two Crystal Awards, Herman Betten is not yet satisfied. He has new plans, as he writes to me: “It is nearly the time to start the preparations for the fourth integrated report. Again, there is the challenge to raise the bar further concerning the contents, the clarity, and the transparency, for being accountable automatically implies being transparent.

The next step toward transparency is clear: The Environmental Profit & Loss, i.e. a calculation in which not just the immediate costs are included but also the indirect costs for mankind and the environment. It is a logical next step as adding value and being transparent not only relates to financial issues.”

The achievement

You are personally accountable with respect to society.

This means:

- You describe your professional activities, their goals and outcomes, and the consequences for all possible stakeholders openly and honestly, in a way that is clearly understandable to all stakeholders.

- You do this for the benefit of your immediate colleagues and your executives. Besides, you do it for the benefit of all kinds of others who are involved or interested. Think of your partner, your children, your parents, your neighbors, reporters, public servants, interest groups, citizens, or schools. For each of them, you select a suitable and appealing way of communicating.

- If it concerns formal reporting, you apply recognized standards for transparency as a minimum criterion, and you work continuously on the improvement of the reporting.

Being held accountable can take the shape of formal reports or of presentations, articles, or books. Besides, there are other less formal means for accounting, for example, through conversations, public discussions, stories, columns, websites, blogs, tweets, online forums, and TV programs.

Accountability is not only about the entire company formally being held accountable, as reported by specialized employees. Accountability is also related to each individual professional, both inside and outside of the company he or she works for. That is why your partner, your children, or your parents, etc. were mentioned.

For the transparency of annual reports, the standards of the Crystal Award offer a valid hold. On the website of the Crystal, the criteria for the transparency benchmark can be downloaded. Some of them are:

Issue 2.2

Does the accounting information offer an explanation about the impact of the own operations on people, the environment, and society?

Explanation: ‘impact’ implies the main consequences (effects on e.g. stakeholders) of the core processes and activities of the organization related to sustainable development (e.g. CO2 emissions, industrial accidents, waste disposal, et cetera).

- No (0 points)

- Yes (2 points)

Issue 8.2

Which of the issues below does the explanation concerning chain responsibility discuss?

Check those issues and indicate where these discussions are to be found in the accountability information:

- Human rights, and the strategic principles and goals the organization applies on this issue. (+1 point)

- Bribery and corruption, and the strategic principles and goals the organization applies on this issue. (+1 point)

- The extent of the policy concerning suppliers, by explaining to which extent demands are posed upon indirect suppliers. (+1 point)

- The explanation does not go into the above issues. (0 points)

Issue 13.1

Does the accountability information contain an explanation about the way in which the dialogue with stakeholders is structured?

- No (0 points)

- Yes (2 points)

Issue 13.2

Does the accountability information offer feedback from the stakeholders themselves?

- No (0 points)

- Yes (+2 points)

Other important norms and guiding lines for transparency are to be found in the already mentioned Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), in ISO 26000, and in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI). Some of the top-ranking companies in 2014 on the DJSI are: Siemens (Germany, category: Capital Goods), Abbott Laboratories (the United States, category: Healthcare Equipment & Services), Unilever (the Netherlands, category: Food, Beverage & Tobacco), Wipro Ltd (India, category: Software & Services), and LG Electronics (the Republic of Korea, category: Consumer Durables & Apparel).