Chapter twelve

Action skills

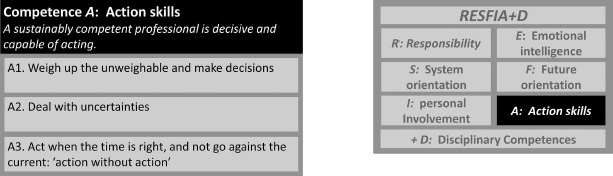

The Competence (Figure 12.1):

A sustainably competent professional is decisive and capable of acting.

Responsibility, emotional intelligence, ethical awareness, passion, and idealism – these are all important characteristics of a sustainably competent professional, and they were all discussed in previous chapters. However, there is one other characteristic without which all these competences are not worth much: the ability to cut the Gordian knot and spring into action. This is the final competence of this book, and you will find it in the present chapter.

Below are the three achievements I will tell you about in this chapter:

- Weigh up the unweighable and make decisions

- Deal with uncertainties

- Act when the time is right, and do not go against the current: “action without action”

For one of my earlier books, I created a series of tasks for my students. One of them involved a letter – not a real one. Gagnon Foods does not exist – I made it up – and both Mr. Rodriguez and Mr. Howard are fictitious, too. As I will show you, the letter illustrates the topics of this chapter. Please read the letter first.

To Mr. Rodriguez,

Manager of Gagnon Foods

Dear Mr. Rodriguez,

I am employed in your Packaging Department, but maybe not for much longer as I fear you will soon fire me. This is because I believe your plans will never work for this company. Mr. Rodriguez, I am well aware that five years ago, you promised that within five years (i.e. now), you would have gotten rid of child labor in our factory in Rajasthan (India). Those children who have to work so hard for you are facing a terrible fate.

Five years ago, the company was doing great, so it was easy to promise something like this, but last year, things started going belly-up and you had to dismiss 20 of my coworkers. I’m pretty sure we were already on the brink of bankruptcy then. Five years ago, you also promised that we would stop buying rice in Rajasthan within five years’ time since they were using poison to get rid of insects, which is bad to the environment. Just last month, you explained in the Gagnon newsletter “Rice and Beans” that it might cost the company money, but that we had to do it because it was socially responsible, and we had to focus on corporate social responsibility. But now I want to ask you: how responsible was this move when you have to fire so many people – people like me? Surely you cannot do that?

I understand that the children in Rajasthan are very young to be working for Gagnon, especially if – as you say – they are only eight years old. But if you fire them and instead hire a group of adults, the latter will certainly be more expensive! Can you cover those additional costs? I don’t think so!

Mr. Rodriguez, I am now 50 years old, and I have worked for your company for 32 years. I worked hard I must add. If I am fired now, I’ll never find another job. I could hit rock bottom and may even start drinking. My wife spends the whole day crying because she is so afraid. She says we should phone somebody at the newspaper or television news. I think that may be a good idea.

Please, Mr. Rodriguez, don’t fire those kids in India. And the rice with the stuff to kill bugs, we’ve been selling it for at least 50 years, so why would our customers want to change? There’s no reason to suddenly stop selling it. Please save me because I’ll be out of options if I were to lose my job!

Your faithful employee,

John Howard

There are a lot of aspects to this letter. You can apply the Triple P nicely: the people aspects are, for example, child labor in Rajasthan and the fears of John Howard and his wife. The planet aspect is apparent in “the stuff to kill bugs” that damages the environment and in the growth of rice, of course. There are also plenty of profit aspects, varying from the higher salary burden when children are replaced by adults to a recent near bankruptcy and the dismissal of 20 employees. When everything was going well, Manager Rodriguez once made a promise that he now feels bound to, but can he live up to it? He faces a nasty dilemma: he will have to weigh issues against each other that are totally incomparable – unweighable. Which is more important: abolishing child labor, saving the environment, or guaranteeing the employees’ jobs? How do you weigh these against each other, for heaven’s sake?

Weigh up the unweighable is one of the achievements this chapter is about. Another achievement is dealing with uncertainties, and Mr. Howard’s letter contains a number of them. There is uncertainty for manager Rodriguez: will the company survive when child labor is banned? Will the harvest be bountiful enough if the rice is grown without pesticides, and how stable will it be in the following years? Will the customers buy the rice, or rather, will they perhaps even demand it? There is uncertainty, too, for Mr. Howard, and probably for many of his colleagues. Will he keep his job? Will he end up in the gutter?

The third achievement in this chapter deals with acting when the time is right. Did Mr. Rodriguez do that five years ago when he made his socially responsible promises? And right now, how can he deal with the present crisis effectively? He must decide how to save the company and keep his personnel satisfied. Also, to what extent can he live up to the promises that are inspired by his conscience?

In the task that involves the letter, students have to discuss the situation and make decisions. I have done the exercise a few times with groups of employees, and I can assure you that it created quite a stir. I won’t bother you with that now. Instead, I will offer you the stories of professionals who dealt with tough situations in a decisive way.

12.1 Weigh up the unweighable

“Negotiating with people that have blood on their hands presents a dilemma for a peace movement. It is a predicament about choices that you can’t weigh against each other. Which is more important: justice or peace?”

This was the dilemma of Jan Gruiters, director of the peace organization PAX. Without a doubt, Joseph Kony, the leader of the infamous Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), consisting mainly of kidnapped child soldiers, had blood on his hands. He founded the rebel group in 1987 with the intention off seizing power in Uganda.

For decades, Joseph Kony, one of the most atrocious warlords in Africa, has in one way or another been able to escape from attempts to capture or kill him. The people living in the countries where the LRA practices its terror – Uganda, Sudan, and Congo – were desperate. What should they do? Negotiate? About what? A safe haven for war criminal Kony, indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC), in exchange for peace? This would mean that Kony would elude justice! Hence, Jan Gruiters’ concern: what should weigh more, justice or peace?

“After graduating with a degree in information technology, I switched from a potentially successful career in the world of automation to an uncertain existence within the peace movement,” Jan Gruiters writes. “In the peace movement, I was able to dedicate my time to what I really found meaningful: war and peace. That personal decision was partly based on World War II, the moral benchmark for the post-war generation.

Driven by ideals, I threw myself into the peace movement. Who was good, who was bad? In those days, it seemed evident. Nelson Mandela was good; the apartheid regime in South Africa was bad. Vaclav Havel was good; the communist government in (the former) Czechoslovakia was bad. Bishop Oscar Romero was good; the military dictatorship in El Salvador was bad.

Through the years, my ideals have not worn out, but for the contemporary wars, the boundaries between good and bad, right and wrong, victims and culprits often seem much less clear. The boundary between perpetration and victimization frequently runs through the heart of one person. To what degree is a child soldier who unscrupulously rapes women an offender or a victim? Is he to be held accountable for his crimes or excused because of a lack of sound societal conditions? Should he be tried or helped?

It becomes even harder when, in order for peace negotiations to begin, it is inevitable to negotiate with people who have blood on their hands, with war criminals who should be in a criminal court rather than at the negotiation table. These are not questions but real dilemmas that belong to the work of a peace organization.”

In his fascinating book No More War – Winning Mission or Lost Vision, which was published in Dutch in 2012, Gruiters writes on a scientific level about dilemmas concerning war and peace. However, Gruiters is not just a theorist. In his work as a director for PAX, he and his organization were repeatedly forced to make painful moral decisions.

“The negotiations with the Lord’s Resistance Army, led by the sinister Joseph Kony, against whom an arrest warrant was issued by the International Criminal Court in The Hague, were a striking example. The violence and raids by the LRA have forced millions of people to flee, mainly Uganda and South Sudan. The LRA kidnapped thousands of children, killed thousands of people. No one succeeded in defeating the LRA or in arresting its leadership. PAX mediated between Joseph Kony and the governments of Uganda and South Sudan, which brought, at least for some time, a truce enabling refugees to return home.”

It was a tough decision, and not everyone agreed with Gruiters. In his letter to me, Gruiters explains how he arrived at his decision.

“Regarding its peace work, PAX is guided by human dignity as its core value. Every human being has a right to a dignified life. Human dignity is the ultimate yardstick for our peace work, based on how we account for our activities to ourselves and to society. Local communities in Uganda and South Sudan invited us to mediate the conflict with the LRA. They were yearning for a dignified existence. The violence, which had created so many victims and would cause many more if nothing was done, had to be stopped. Mediating the conflict was more urgent than simply bringing Joseph Kony to court. The human dignity of innocent civilians weighed the heaviest, not our sense of justice. It was a choice that raised a lot of discussion within and outside of the peace movement.”

PAX first attempted to start negotiations in 1998, but neither Kony nor the governments of Uganda and Sudan were prepared to negotiate. Only toward the end of 2005 did PAX formally receive the request from Sudan and the LRA to mediate between the parties. It was not until May 18, 2006, that newspapers reported President Museveni of Uganda was also prepared to join. For a number of years, violence decreased, but regrettably it did not last. In 2012, the international attention for the drama of the LRA increased strongly and attempts to catch Kony intensified. This was partly due to an impressive documentary called “Kony 2012,” which was placed on YouTube by the organization Invisible Children, Inc. and viewed a hundred million times within a month. Even though negotiations did not lead to a peace treaty, violence has since declined. But at the time I am writing this text, Kony and his LRA are still wandering freely. The international community does not seem prepared to launch serious attempts to arrest him.

“The reality of armed conflicts confronts us with complex dilemmas,” Gruiters writes, “dilemmas that go beyond the simple schemes of good and bad. In situations where we have to weigh the unweighable rationally and emotionally, we are well advised to make the values that are guiding the actions of humans explicit. In such cases, we have to rely on our moral yardstick. It is not the functional rationality that is so dominantly available in our times but the orientation toward values that can help us weigh the dilemmas properly and make decisions. It implies that a choice to be made in a stubborn reality of war or peace is often a choice for the lesser evil.”

The achievement

You weigh up the unweighable and make decisions.

This means:

- You recognize and acknowledge situations in your professional activities in which interests that cannot be compared in an unambiguous way have to be weighed against each other.

- You discuss decisions with the involved stakeholders or their representatives. You consider the values of all those who have an interest in these decisions, including yourself.

- Partially based on this, you rationally weigh the pros and cons and make decisions. You explain your decisions to the stakeholders or their representatives.

- You investigate whether there are options to make the conflicting interests less so. You investigate whether there are ways to compensate those who suffer from the negative consequences of your decisions.

Incompatible interests are not only found in the area of war and peace but also in the following examples: starting a company that is beneficial for the local economy but detrimental for the local environment; offering extra care for students or patients at the expense of less care for other students or patients or your own health or well-being; designing a product that causes fewer emissions of greenhouse gases but demands more scarce materials; setting up activities for underprivileged young people in a way that makes nearby residents unhappy – “nimby” (not in my backyard)!

Sometimes such dilemmas are about conflicting interests of people versus planet, for instance, when you grow crops for biofuel: good against climate change but bad for poor people since the increasing demand for agricultural land leads to higher food prices.

Sometimes it is about the interests of profit versus people, for instance, when you combat child labor or try to raise extremely low wages while harming the competitive position of certain companies.

It may even be about people versus people. When you revitalize urban neighborhoods, residents welcome the change until they can no longer afford the rent. In this case, wealthier people moving into the newly gentrified areas benefit.

In short, when it comes to complex sustainability issues, there are hardly any simple, straightforward solutions. That’s how life is. A sustainably competent professional does not have to find all this easy, but he or she will eventually find ways to deal with these challenges.

Stakeholders are not always able to defend their interests themselves. In that case, representatives can do it for them. If children are concerned, you may think of parent organizations or of Child Protective Services. Mentally challenged people have their own organizations, too. When animals, or more generally speaking, nature or the environment are stakeholders, all kinds of action groups exist, varying from local groups such as “Friends of the Crooked River” in Ohio to national organizations like the Sierra Club to global ones like the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). It is possible to compensate for harmful consequences, for example, by planting trees as a CO2 offset or by paying compensation for lost nature. If understaffing causes problems, you can expand your team to offer sufficient care for all students or patients. If noise pollution bothers nearby residents, build a sound barrier and make sure you select biodegradable materials.

12.2 Deal with uncertainties

Action skills, the topic of this chapter, may not only be hindered by nearly impossible dilemmas but also by a lack of certainties. The future is unknown. What will happen in the coming months, years, or decades? Nobody knows. But also the present – and even the past – are not fully known. If you get paralyzed by uncertainty or fear as a professional, your ability to make decisions and your action skills go down the drain.

One way to deal with uncertainties is the use of a technique called “backcasting.” Why is this process called “backcasting?” Most notably, forecasting is impossible due to the many uncertainties. As lots of trend watchers and futurologists keep proving to us over and over: the future is unpredictable! With backcasting, you don’t go from the present to the future, but quite the opposite, you move backward from a range of possible futures toward now. This enables a group of creative people to explore all kinds of futures and decide which of them are appealing and which are not. They can then determine which steps to take now to make the appealing scenarios more likely, and also which steps will most certainly not lead there.

Someone who applies this tool regularly as part of his job is Pong Leung, Senior Associate for The Natural Step, Canada, a non-profit organization that offers sustainability consulting involving backcasting to individuals, businesses, municipalities, and institutions. While still in college, Pong read Paul Hawken’s The Ecology of Commerce and found it inspiring. “In business school, they didn’t talk about sustainability,” he says, but the topic fascinated him, and he had “a lot of questions about it.” Eventually, he obtained a Master’s of Science in environmental management and policy at the International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics at Lund University in Sweden and joined The Natural Step.

One of Pong’s recent clients, ISL Engineering and Land Services, approached him after a survey of their 50 largest clients had revealed sustainability as their most important need and the fact that ISL’s employees had started their own green team. At the initial meeting with ISL’s leadership, Pong and his colleagues guided the conversation in a strategic direction: “The first thing we try to do is find out what the strategic relevance of sustainability is for them. For example, we often share three areas where we have found sustainability to create lasting value: enhancing brand reputation, driving innovation, and fostering a culture of excellence. One or more of them will resonate, and then we explore that further. It is important that we explore the “why”, because backcasting is an investment.”

To help understand the “why”, they first help the business take stock of the current situation via stakeholder interviews, surveys, a review of key documents, and a best practices scan. “Change is uncomfortable. It’s disruptive,” Pong admits, “but companies see the writing on the wall … In interview sessions with the senior leaders, we get a sense of the company’s hopes and fears.” A lot of times, he says, demands from stakeholders convince companies to embrace sustainability. “You can ignore your stakeholders, but is that smart?” Pong asks.

This sets the stage to apply backcasting via the ABCD method pioneered by The Natural Step. Pong leads his clients from Awareness and Visioning to Baseline Mapping, i.e. a “gap analysis”, and from there to Creative Solutions and Deciding on Priorities. “We help the organization integrate sustainability into their strategy, culture and operations. They recognize that it means starting with the end in mind, and taking an honest look at their current situation … As a company, you want to build on your strengths, but you are also looking to move to a different place.”

Clarifying the gap between desired future and current reality allows groups to make decisions on actions in spite of uncertainties by answering three key questions: “Does it move us in the right direction? Is it a flexible platform for future steps? And does it generate sufficient return on investment? In short, does it make business sense in the near- and long-term? We try to make the sessions interactive and help them align with the future they want to create,” Pong explains.

The consulting typically takes place over an extended time. Pong says, “We always frame it as a 3–7 year change initiative. During the first three years, we are more actively involved. Then less as sustainability becomes part of the company’s culture. When there are bumps in the road or when specific issues arise, we come in for a boost.” In ISL’s case, the efforts paid off. Not long after the initial engagement, it was included on the Green 30 list as one of Canada’s most environmentally progressive employers.

What Pong Leung enjoys most about his job is “helping others make a difference and helping organizations move forward.” Especially now that he has children, he feels that “work isn’t just what you do for a living; it’s making a contribution.” In the end, the consultant’s job is finished not after handing over pieces of advice but when clients have the capacity to arrive at their own conclusions in the face of uncertainty.

The achievement

You deal with uncertainties.

This means:

- You carefully estimate the level of uncertainty of the information you use for your professional activities.

- You plan your professional activities while taking uncertainties into consideration; if necessary, you take appropriate actions.

- You apply the precautionary principle: You choose your plans and methods in a way that minimizes uncertainties of crucial importance whenever possible.

- You apply effective methods to reach responsible and accepted decisions, taking into account the inevitable uncertainties.

Uncertainty can result from a variety of causes. You may think of:

- uncertainty due to a lack of information, inaccurate information, potentially unreliable information, or information from contradicting sources.

- uncertainty about delivery times, purchase prices, markets, legal regulations, or your own production quality.

- uncertainty about applied scientific models or technological or medical solutions. Have they been proved accurate (“evidence based”)? Are they sufficiently accepted?

- uncertainty about the reactions you may get to certain events or developments, for instance, to decisions you might make. This may involve reactions to physical systems (a machine, a plant, a forest, a robot), but it may also involve a person or a group of people (customers, clients, student, or patients; the staff, the union, a country).

- uncertainty about support or resistance you may receive.

- uncertainty regarding the whims of the system. What is true today may turn out to be a lie tomorrow.

- uncertainty about shifting values: what is important, and who gets to decide?

- finally, uncertainty about yourself: do I want this? Can I do it? Do I have the guts? Do I possess the necessary perseverance?

You can deal with uncertainties in many ways. You may postpone decisions and first seek more information, for instance, by conducting additional research to support a claim, perhaps preceded by a stakeholder analysis. Of course, you can also sit back and make no decision at all. You probably know that this does not work well: no decision is a decision, too. If you do nothing and freeze, the world does not freeze, and eventually everything will overwhelm you. Nevertheless, sometimes the “zero option” may be a good decision since certain problems that you were initially very worried about all of a sudden stop being problems, disappearing like snow under the heat of the sun. Have you seen it happen?

You may also deal with uncertainties by minimizing the risks of potentially negative effects. In that case, you apply the precautionary principle.

Do you have insurance? Probably you do. Most likely, you have a bunch of different policies: against fire, burglary, disease, accidents, car trouble, liability, unemployment, death, etc. In addition, you have probably taken other precautions such as locks on the door, a bicycle pump, spare keys, condoms, bandages, vaccinations, and an emergency fund. Collectively, we even have much more: the fire brigade, the police, the Armed Forces, levees, early warning systems, disaster plans, emergency supplies, and a vice-president. They are all expressions of the precautionary principle. In short, everybody safeguards against something that might go wrong.

To sustainability, the precautionary principle is highly relevant. As metals, oil, and gas will (likely) become more expensive in the future because of scarcity and depletion, many companies are investing in alternative materials and sustainable sources of energy. The debates about climate change are still continuing (and may do so indefinitely), and yet, governments and companies spend billions to combat the negative effects.

- Unweighable considerations weighed.

- Impossible decisions made.

- Confounding uncertainties overcome or passed.

- Time for action.

12.3 Action without action

Doing without doing; action without action – a nice paradox. It sounds impossible, but it isn’t since the first “action” means something different than the second. The first “action” stands for “achieve something, act successfully.” The second “action” signifies “force, push, impose, and exert pressure.” In other words, “action without action” implies: “be effective without forcing, or act at the right moment, in a suitable way.”

The expression “action without action,” which comes from Chinese – where it sounds like wei wu wei – has existed for a long time. The principle stems from the Tao Te Ching (or Daoteching), the famous book by the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu (or Laozi), the founder of Taoism (Daoism), who lived probably between 600–500 BCE. The principle is easy to understand. Imagine a child sitting on a swing, asking you to push. Of course, you give the first push only once the child is sitting down and holding on firmly. But the second and successive ones? You’d better not push at the moment when the child comes flying toward you at full speed. If you do, you will definitely break the momentum and perhaps even your wrist. The best you can do is wait until the swing roughly reaches its highest point of motion, and then give a light push. This does not require much strength. A series of such pushes, given at just the right moment, adds up to a fabulous result. That is “action without action.” Swimming in a river, along with the current as opposed to against it or across, also captures the principle of action without action – making use of existing forces and motions instead of fighting them.

Having studied under recognized Master Meng Zhiling, Vice-President of the Chinese Taoist Association, David Hessler believes that “wu wei should be applied to everywhere in one’s life.” Hessler, the founder of the US Taoist Association, leads student trips to China and teaches history at Montclair Kimberley Academy in New Jersey. He shares a story Master Meng told him:

One day, Master Meng, who was living as a hermit in the mountains, was approached by local villagers with a question. The villagers had invested in a power company, but recently, the machines weren’t working properly, and now they were losing money. Apparently, previously, there had been an older man in charge, but the villagers felt he never did anything, so they had fired him and instead had hired two younger men who understood technology well. However, things hadn’t gotten better, the villagers lamented. What should they do, they asked? Master Meng listened carefully and finally advised, “Hire the old mechanic back.” The villagers were perplexed. “But he never did anything,” they said. “Exactly!” Master Meng explained. The old mechanic did not have to do anything because he understood when to act, solving minor issues before they became big problems, thus making it seem effortless – action at the right moment. If the older man trained the younger men to practice wu wei, they, too, would learn to recognize potential trouble in time, the hermit told them.

“Acting at the ‘right moment’ is acting according to wu wei,” Hessler argues. “But it is also understanding the nature of the situation one is in and what is required of the person at that moment. The way one understands what is the right moment is complicated. That comes when one can see the situation clearly without personal prejudice or bias. When you can do that, then you see any situation very clearly and act in accordance with what is actually called for.”

To help his own high school students better understand wu wei, Hessler engages them with examples from sports, for example, soccer or basketball. An experienced point guard, he tells them, knows precisely when a teammate will be in an open space and passes the ball at just the right moment without having to think about it. When players are in the “zone” or in the “flow,” dribbling and shooting become second nature just like walking or breathing. “You’re acting without an ego,” Hessler says. “Maybe the best metaphor for wu wei is water: It never forces things but goes under or around when its way is blocked. Also, water benefits without seeking attention. All life depends on water.”

As an educator, Hessler applies wu wei in his daily work and recently published an article called “Teaching with Tao” in the Journal of Daoist Studies. “If the teacher understands the nature of the student, for example, whether he or she is a visual or an auditory learner, then the teacher automatically adjusts. An experienced teacher doesn’t have to think about it. He or she just does it. It’s not about you, but about the student. Master Meng always cautions his followers not to seek attention and fame.”

So, how can you learn to act without acting – or at just the right moment? The answer begins with creating that open space in your mind. “All of this is predicated on the fact that you have to have a mind that is quiet so that you can see clearly what the next thing that needs to be done is,” Hessler, who has been meditating for over ten years, suggests. Wu wei, Hessler thinks, ultimately “has to do with what the best benefit is. It’s about you going through life in the most ethical way. That’s a hard thing to do. It’s not like you adopt it. You begin to think about it, and then – gradually – it begins to become a part of you.”

The achievement

You act when the time is right, and do not go against the current: “action without action.”

This means:

- You act at the right moment. No sooner, no later.

- You endeavor to acquire the largest possible support, if possible even consensus.

- For this purpose, you estimate the resistance stakeholders might have against the intended actions. You discover at which moment this resistance may be relatively low, and you design the time schedule accordingly.

- If you discover that resistance will diminish too slowly or not at all, or in order to increase support, you redesign your activities, aiming at a more acceptable process and result. You involve the stakeholders in this process.

An important reason to wait for the right moment to do something is when you encounter resistance. It can be present within individuals or even in groups. However, the timing of physical systems may also cause resistance, for example, industrial processes, delivery times, biological systems, train failures, traffic jams, the unpredictable weather, or the season.

Sometimes resistance is hidden within “pretexts.” As a consultant, I have heard repeatedly from certain managers that it was not a good time to introduce sustainability or CSR at the moment: “as the organization is in the middle of a change process right now.”

When determining exactly at which moment the resistance of individuals or groups is minimal, you should, of course, refrain from taking advantage of the circumstances, for instance, when the involved persons are absent (due to a holiday) or vulnerable (due to illness, fatigue, or distracted attention). What you can do is wait until the support from the involved parties has grown. You might also wait until they are in a suitable state to consider the actions. You could also actively stimulate the decision process, for instance, by providing information, resolving misunderstandings, and listening actively to objections. Search for alternatives together. Set up preparatory activities (“plow the land and sow before you start harvesting”) in such a way that resistance doesn’t increase but diminishes. Start or restart discussions that involve all stakeholders in an equal way.